Abstract

Effective therapeutic options for patients living with chronic pain are limited. The pain relieving effect of cannabinoids remains unclear. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining cannabinoids in the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain was conducted according to the PRISMA statement update on the QUORUM guidelines for reporting systematic reviews that evaluate health care interventions. Cannabinoids studied included smoked cannabis, oromucosal extracts of cannabis based medicine, nabilone, dronabinol and a novel THC analogue. Chronic non-cancer pain conditions included neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed chronic pain. Overall the quality of trials was excellent. Fifteen of the eighteen trials that met the inclusion criteria demonstrated a significant analgesic effect of cannabinoid as compared with placebo and several reported significant improvements in sleep. There were no serious adverse effects. Adverse effects most commonly reported were generally well tolerated, mild to moderate in severity and led to withdrawal from the studies in only a few cases. Overall there is evidence that cannabinoids are safe and modestly effective in neuropathic pain with preliminary evidence of efficacy in fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. The context of the need for additional treatments for chronic pain is reviewed. Further large studies of longer duration examining specific cannabinoids in homogeneous populations are required.

Linked Article

This article is linked to a themed issue in the British Journal of Pharmacology on Respiratory Pharmacology. To view this issue visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2011.163.issue-1

Keywords: cannabinoids, chronic non-cancer pain, neuropathic pain, systematic review

Introduction

Chronic pain is common and debilitating with too few effective therapeutic options. Cannabinoids represent a relatively new pharmacological option as part of a multimodel treatment plan. With increasing knowledge of the endocannabinoid system [1–3] and compelling preclinical work supporting that cannabinoid agonists are analgesic [4, 5] there is increasing attention on their potential role in the management of pain [6–9]. A previous systematic review done a decade ago identified the need for further randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating cannabinoids in the management of chronic pain indicating that there was insufficient evidence to introduce cannabinoids into widespread use for pain at that time [10]. A subsequent review identified a moderate analgesic effect but indicated this may be offset by potentially serious harm [11]. This conclusion of serious harm mentioned in the more recent review is not consistent with our clinical experience. In addition there have been a number of additional RCTs published since this review. We therefore conducted an updated systematic review examining RCTs of cannabinoids in the management of chronic pain.

Methods

We followed the PRISMA update on the QUORUM statement guidelines for reporting systematic reviews that evaluate health care interventions [12].

Systematic search

A literature search was undertaken to retrieve RCTs on the efficacy of cannabinoids in the treatment for chronic pain. The databases searched were: PubMed, Embase, CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycInfo (EBSCO), The Cochrane Library (Wiley), ISI Web of Science, ABI Inform (Proquest), Dissertation Abstracts (Proquest), Academic Search Premier (EBSCO), Clinical Trials.gov, TrialsCentral.org, individual pharmaceutical company trials sites for Eli Lilly and GlaxoSmithKline, OAIster (OCLC) and Google Scholar. None of the searches was limited by language or date and were carried out between September 7 and October 7, 2010. The search retrieved all articles assigned the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) Cannabis, Cannabinoids, Cannabidiol, Marijuana Smoking and Tetrahydrocannibinol as well as those assigned the Substance Name tetrahydrocannabinol-cannabidiol combination. To this set was added those articles containing any of the keywords cannabis, cannabinoid, marijuana, marihuana, dronabinol or tetrahydrocannibinol. Members of this set containing the MeSH heading Pain or the title keyword ‘pain’ were passed through the ‘Clinical Queries: therapy/narrow’ filter to arrive at the final results set. For the pain aspect, the phrase ‘Chronic pain’ along with title keyword ‘pain’ was used to retrieve the relevant literature. We contacted authors of original reports to obtain additional information. Bibliographies of included articles were checked for additional references.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included were RCTs comparing a cannabinoid with a placebo or active control group where the primary outcome was pain in subjects with chronic non-cancer pain. Relevant pain outcomes included any scale measuring pain, for example the numeric rating scale for pain (NRS), visual analogue scale for pain (VAS), the Neuropathy Pain Scale or the McGill Pain Scale. We excluded (i) trials with fewer than 10 participants, (ii) trials reporting on acute or experimental pain or pain caused by cancer, (iii) preclinical studies and (iv) abstracts, letters and posters where the full study was not published.

Data extraction and validity scoring

One author (ML) did the initial screen of abstracts, retrieved reports and excluded articles that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. Both authors independently read the included articles and completed an assessment of the methodological validity using the modified seven point, four item Oxford scale [13, 14] (Figure 1). After reading the complete articles it was clear that several additional papers did not meet inclusion criteria and these were excluded. Discrepancies on the quality assessment scale were resolved by discussion. Trials that did not include randomization were not included and a score of 1 on this item of the Oxford scale was required and the maximum score was 7.

Figure 1.

Modified Oxford scale

Information about the specific diagnosis of pain, agent and doses used, pain outcomes, secondary outcomes (sleep, function, quality of life), summary measures, trial duration and adverse events was collected. Information on adverse events was collected regarding serious adverse events, drug related withdrawals and most frequently reported side effects. A serious adverse event according to Health Canada and ICH1 guidance documents is defined as any event that results in death, is life threatening, requires prolonged hospitalization, results in persistent of significant disability or incapacity or results in congenital anomaly or birth defects [15].

Results

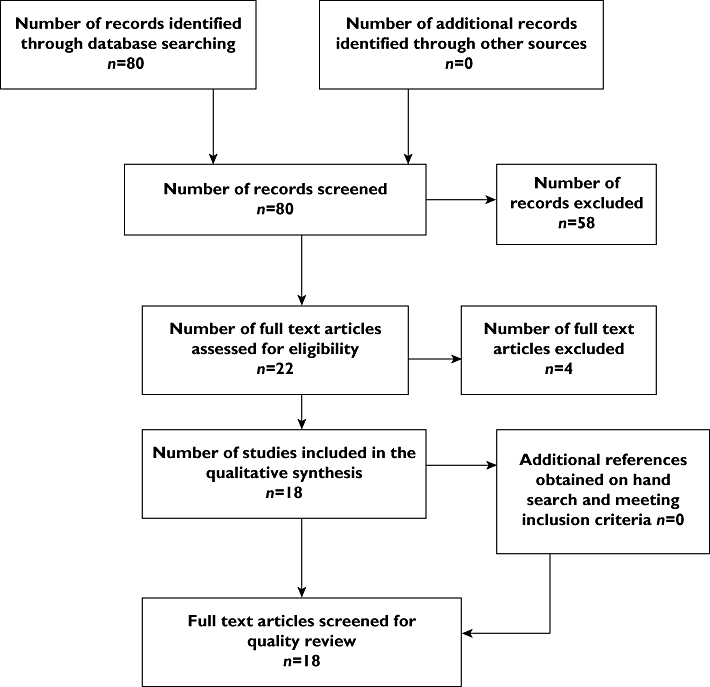

Trial flow

Eighty abstracts were identified of which 58 did not meet inclusion criteria on the initial review of records (Figure 2). Twenty-two RCTs comparing a cannabinoid with either a placebo or active control group where pain was listed as an outcome were found and full text articles were reviewed, four further studies were excluded, two because pain was not the primary outcome (Zajicek [16, 17]), one because there were fewer than 10 participants in the study (Rintala [18]). A further study was excluded because there were two studies reporting on what appeared to be the same group of participants (Salim [19], Karst [20]), in this case we included the first study in which the pain outcomes were reported (Karst). References of the included trials were reviewed for additional trials meeting inclusion criteria. This revealed no further studies. Eighteen trials met the study criteria for inclusion. We did not retrieve any unpublished data. Given the different cannabinoids, regimens, clinical conditions, different follow-up periods, and outcome measures used in these trials, pooling of data for meta-analysis was inappropriate. Results were therefore summarized qualitatively.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of systematic review

Primary outcome – efficacy

Eighteen trials published between 2003 and 2010 involving a total of 766 completed participants met inclusion criteria (Table 1). The quality of the trials was very good with a mean score of 6.1 on the 7 point modified Oxford scale. The majority (15 trials) demonstrated a significant analgesic effect for the cannabinoid agent being investigated. Several trials also noted significant improvements in sleep [21–24]. Treatment effects were generally modest, mean duration of treatment was 2.8 weeks (range 6 h–6 weeks) and adverse events were mild and well tolerated.

Table 1.

Randomized controlled trials examining cannabinoids in treatment of chronic non-cancer pain

|

Cannabis

Four trials examined smoked cannabis as compared with placebo. All examined populations with neuropathic pain and two involved neuropathic pain in HIV neuropathy [21, 25–27]. All four trials found a positive effect with no serious adverse effects. The median treatment duration was 8.5 days treatment (range 6 h–14 days).

Oromucosal extracts of cannabis based medicine (CBM)

Seven placebo controlled trials examined CBM [22–24, 28–30]. Five examined participants with neuropathic pain, one rheumatoid arthritis and one a mixed group of people with chronic pain, many of whom had neuropathic pain. Six of the seven trials demonstrated a positive analgesic effect. Of note in the one trial examining pain in rheumatoid arthritis, the CBM was associated with a significant decrease in disease activity as measured by the 28 joint disease activity score (DAS28) [23].

Nabilone

Four trials studied nabilone [31–34]. Three of these trials were placebo controlled and found a significant analgesic effect in spinal pain [34], fibromylagia [32] and spasticity related pain [33]. The fourth compared a daily dose of nabilone 2 mg with dihydrocodeine 240 mg in neuropathic pain. Mean baseline pain was 69.6 mm on the 100 mm VAS and dropped to 59.93 mm for participants taking nabilone and 58.58 mm for those taking dihydrocodeine [31].

Dronabinol

Two trials involved dronabinol. The earlier trial found that dronabinol 10 mg day−1 led to significant reduction in central pain in multiple sclerosis [35], a subsequent trial found that dronabinol at both 10 and 20 mg day−1 led to significantly greater analgesia and better relief than placebo as adjuvant treatment for a group of participants with mixed diagnoses of chronic pain on opioid therapy [36].

THC-11-oic acid analogue (CT-3 or ajulemic acid)

Two studies reported on various aspects of this trial examining ajulemic acid in a group of participants with neuropathic pain with hyperalgesia or allodynia [37, 38]. Nineteen of 21 completed the trial. It was found that ajulemic acid led to significant improvement in pain intensity at 3 h but no difference at 8 h as compared with placebo.

Secondary outcome – level of function

Several trials included secondary outcome measures relating to level of function. Two trials examining cannabis based medicines included the Pain Disability Index (PDI) [24, 30]. Numikko found that six of seven functional areas assessed by the PDI demonstrated significant improvement on CBM (−5.61) as compared with placebo (0.24) (estimated mean difference −5.85, P = 0.003) in 125 participants with neuropathic pain while Berman [24] noted no significant difference from placebo in 48 participants with central pain from brachial plexus avulsion. Two studies included the Barthel index for activities of daily living (ADL) [28, 33] and noted no significant improvement in ADLs with nabilone for spasticity related pain [33] or with CBMs for multiple sclerosis [28]. In one trial examining nabilone for the treatment of fibromyalgia the FIQ [39] demonstrated significant improvement as compared with placebo. This measure includes a number of questions regarding function in several areas including shopping, meal preparation, ability to do laundry, vacuum, climb stairs and ability to work. The FIQ also includes questions relating to pain, fatigue, stiffness and mood. The total scores presented in this study were not presented separately so the reader cannot be certain. However given that the majority of questions relate to function it is likely that there were some improvements in function.

Drug related adverse effects

There were no serious adverse events according to the Health Canada definition described above and in Table 1, The most common adverse events consisted of sedation, dizziness, dry mouth, nausea and disturbances in concentration. Other adverse events included poor co-ordination, ataxia, headache, paranoid thinking, agitation, dissociation, euphoria and dysphoria. Adverse effects were generally described as well tolerated, transient or mild to moderate and not leading to withdrawal from the study. This is a significant difference from the withdrawal rates seen in studies of other analgesics such as opioids where the rates of abandoning treatment are in the range of 33% [40]. Except where specifically noted in Table 1 there was no specific mention of whether adverse effects caused limitations in function. The most severe treatment related event in the entire sample was a fractured leg related to a fall that was thought to be related to dizziness [34]. Details regarding specific trials are presented in Table 1.

Discussion

Efficacy and harm

All of the trials included in this review were conducted since 2003. No trials prior to this date satisfied our inclusion criteria. This review has identified 18 trials that taken together have demonstrated a modest analgesic effect in chronic non-cancer pain, 15 of these were in neuropathic pain with five in other types of pain, one in fibromyalgia, one in rheumatoid arthritis, one as an adjunct to opioids in patients with mixed chronic pain and two in mixed chronic pain. Several trials reported significant improvements in sleep. There were no serious adverse events. Drug related adverse effects were generally described as well tolerated, transient or mild to moderate and most commonly consisted of sedation, dizziness, dry mouth, nausea and disturbances in concentration.

Limitations

The main limitations to our findings are short trial duration, small sample sizes and modest effect sizes. Thus there is a need for larger trials of longer duration so that efficacy and safety, including potential for abuse, can be examined over the long term in a greater number of patients. It is also important to recognize that cannabinoids may only reduce pain intensity to a modest degree. It remains for the patients to decide whether this is clinically meaningful.

The context of chronic pain

Pain is poorly managed throughout the world. Eighty percent of the world population has no or insufficient access to treatment for moderate to severe pain [41]. Chronic pain affects approximately one in five people in the developed world [42–46] and two in five in less well resourced countries [47]. Children are not spared [48, 49] and the prevalence increases with age [43, 50]. The magnitude of the problem is increasing. Many people with diseases such as cancer, HIV and cardiovascular disease are now surviving their acute illness with resultant increase in quantity of life, but in many cases, poor quality of life due to persistent pain caused either by the ongoing illness or nerve damage caused by the disease after resolution or cure of the disease. In many cases the pain is also caused by the treatments such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy needed to treat the disease [51–53].

Chronic pain is associated with the worst quality of life as compared with other chronic diseases such as chronic heart, lung or kidney disease [50]. Chronic pain is associated with double the risk of suicide as compared with those living with no chronic pain [54].

In this context, patients living with chronic pain require improved access to care and additional therapeutic options. Given that this systematic review has identified 18 RCTs demonstrating a modest analgesic effect of cannabinoids in chronic pain that are safe, we conclude that it is reasonable to consider cannabinoids as a treatment option in the management of chronic neuropathic pain with evidence of efficacy in other types of chronic pain such as fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis as well. Of special importance is the fact that two of the trials examining smoked cannabis [25, 26] demonstrated a significant analgesic effect in HIV neuropathy, a type of pain that has been notoriously resistant to other treatments normally used for neuropathic pain [52]. In the trial examining cannabis based medicines in rheumatoid arthritis a significant reduction in disease activity was also noted, which is consistent with pre-clinical work demonstrating that cannabinoids are anti-inflammatory [55, 56].

Conclusion

In conclusion this systematic review of 18 recent good quality randomized trials demonstrates that cannabinoids are a modestly effective and safe treatment option for chronic non-cancer (predominantly neuropathic) pain. Given the prevalence of chronic pain, its impact on function and the paucity of effective therapeutic interventions, additional treatment options are urgently needed. More large scale trials of longer duration reporting on pain and level of function are required.

Footnotes

International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rice ASC, Farquhar-Smith WP, Nagy I. Endocannabinoids and pain: spinal and peripheral analgesia in inflammation and neuropathy. Prostaglandins, Leuktrienes Essential Fatty Acids. 2002;66:243–56. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson SJ, Benson JA, Joy JE. Marijuana and medicine: assessing the science base: a summary of the 1999 Institute of Medicine Report. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:547–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicoll RA, Alger BE. The brain's own marijuana. Scientific American. 2004;291:68–75. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1204-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohmann AG, Suplita RL. Endocannabinoid mechanisms of pain modulation. AAPS J. 2006;8:E693–708. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080479. Article 79. Available at http://www.aapsj.org/view.asp?art = aapsj080479 (last accessed 24 April 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guindon J, Hohmann AG. The endocannabinoid system and pain. CNS Neurol Dis Drug Targets. 2009;8:403–21. doi: 10.2174/187152709789824660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand P, Whiteside G, Fowler CJ, Hohmann AG. Targeting CB2 receptorsand the endocannabinoid systemfor the treatment of pain. Brain Res Rev. 2008;60:255–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahn EJ, Hohmann AG. Cannabinoids as pharmacotherapies for neuropathic pain: from the bench to bedside. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:713–37. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guindon J, Hohmann AG. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: a therapeutic target for the treatment of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:319–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pertwee R. Emerging strategies for exploiting cannabinoid receptor agonists as medicines. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:397–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell FA, Tramer MR, Carroll D, Reynolds JM, Moore RA. Are cannabinoids an effective and safe treatment option in the management of pain? A qualitative systematic review. BMJ. 2002;323:1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin-Sanchez E, Furukawa TA, Taylor J, Martin JLR. Systematic review and meta-analysis of cannabis treatment for chronic pain. Pain Med. 2009;10:1353–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ionnidis JPA, CLarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemio. 2009;62:e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elia N, Tramer MR. Ketamine and postoperative pain-a quantitative systematic review. Pain. 2005;113:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health Canada adopted ICH Guidance. Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1997. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zajicek J, Fox P, Sanders H, Wright D, Vickery J, Nunn A, Thompson A, UK MS Research Group Cannabinoids for treatment of spasticity and other symptoms related to multiple sclerosis (CAMS study): multicentre rendomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:1517–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zajicek JP, Sanders HP, Wright DE, Vickery PJ, Ingram WM, Reilly SM, Nunn AJ, Teare LJ, Fox PJ, Thompson AJ. Cannabinoids in multiple sclerosis (CAMS) study: safety and efficacy data for 12 months follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1664–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.070136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rintala DH, Fiess RN, Tan G, Holmes SA, Bruel BM. Effect of dronabinol on central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89:840–8. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181f1c4ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salim K, Schneider U, Burstein S, Hoy L, Karst M. Pain measurements and side effect profile of the novel cannabinoid ajulemic acid. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karst M, Salim K, Burstein S, Conrad I, Hoy L, Schneider U. Analgesic effect of the synthetic cannabinoid CT-3 on chronic neuropathic pain. JAMA. 2003;290:1757–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware MA, Wang T, Shapiro S, Robinson A, Ducruet T, Huynh T, Gamsa A, Bennett G, Collett JP. Smoked cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2010;182:1515–21. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rog DJ, Numikko TJ, Friede T, Young AC. Randomized controlled trial of cannabis based medicine in central pain due to multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;65:812–19. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176753.45410.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blake DR, Robson P, Ho M, Jubb RW, McCabe CS. Preliminary assessment of the efficacy, tolerability and safety of a cannabis-based medicine (Sativex) in the treatment of pain caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2006;45:50–2. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berman JS, Symonds C, Birch R. Efficacy of two cannabis based medicinal extracts for relief of central neuropathic pain from brachial plexus avulsion: results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2004;112:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrams D, Jay CA, Shade SB, Vizoso H, Reda H, Press S, Kelly ME, Rowbotham MC, Peterson KL. Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy, a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:515–21. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000253187.66183.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis R, Toperoff W, Vaida F, ven den Brande G, Gonzales J, Gouaux B, Bentley H, Atkinson JH. Smoked medicinal cannabis for neuropathic pain in HIV: a randomized, crossover, clinical trial. Neuropsychopharm. 2009;34:672–80. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilsey B, Marcotte T, Tsodikov A, Millman J, Bentley H, Gouaux B, Fishman S. A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of cannabis cigarettes in neuropathic pain. J Pain. 2008;9:506–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wade DT, Makela P, Robson P, House H, Bateman C. Do cannabis based medicinal extracts have general or specific effects on symptoms in multiple sclerosis? A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study on 160 patients. Mutiple Scler. 2004;10:434–41. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1082oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wade DT, Robson P, House H, Makela P, Aram J. A preliminary controlled study to determine whether whole-plant cannabis extracts can improve intractable neurogenic symptoms. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:21–9. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr581oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Numikko TJ, Serpell MG, Hoggart B, Toomey PJ, Morlion BJ, Haines D. Sativex successfully treats neuropathic pain characterized by allodynia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial. Pain. 2007;133:210–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank B, Serpell MG, Hughes J, Matthews NS, Kapur D. Comparison of analgesic effects and patient tolerability of nabilone and dihydrocodeine for chronic neuropathic pain: randomised, crossover, double blind study. BMJ. 2008;336:199–201. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39429.619653.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skrabek RQ, Galimova L, Ethans K, Perry D. Nabilone for the treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2008;9:164–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wissell J, Haydn T, Muller JE, Schelosky LD, Brenneis C, Berger T, Poewe W. Low dose treatment with the synthetic cannabinoid Nabilone significantly reduces spasticity-rleated pain. J Neurol. 2006;253:1337–41. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinsger M, Schimetta W, Volc D, Hiermann E, Riederer F, Polz W. Benefits of an add-on treatment with the synthetic cannabinomimetic nabilone on patients with chronic pain-a randomized controlled trial. Wein Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118:327–35. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svendsen KB, Jensen TS, Bach FW. Does the cannabinoid dronabinol reduce central pain in multiple sclerosis? Randomised double blind placebo controlled crossover trial. BMJ. 2004;329:253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38149.566979.AE. Epub 2004 Jul 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narang S, Gibson D, Wasan AD, Ross EL, Michna E, Nedeljkovic SS, Jamison RN. Efficacy of dronabinol as an adjuvant treatment for chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. J Pain. 2008;9:254–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karst M, Salim K, Burstein S, Conrad I, Hoy L, Schneider U. Analgesic effect of the synthetic cannabinoid CT-3 on chronic neuropathic pain. JAMA. 2003;290:1757–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salim K, Schneider U, Burstein S, Hoy L, Karst M. Pain measurements and side effect profile of the novel cannabinoid ajulemic acid. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett R. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ): a review of its development, current version, operating characteristics and uses. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S154–S62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furlan AD, Sandoval JA, Mailis-Gagnon A, Tunks E. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effects. CMAJ. 2006;174:1589–94. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohman D, Schleifer R, Amon JJ. Access to pain treatment as a human right. BMC Med. 2010;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-8. Available at http:/www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/8/8 (last accessed 24 April 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127–34. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moulin D, Clark AJ, Speechly M, Morley-Forster P. Chronic pain in Canada, prevalence, treatment, impact and the role of opioid analgesia. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7:179–84. doi: 10.1155/2002/323085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eriksen J, Jensen MK, Sjogren P, Ekholm O, Rasmusen NK. Epidemiology of chronic non-malignant pain in Denmark. Pain. 2003;106:221–28. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huijer Abu-Saad H. Chronic pain: a review. J Med Liban. 2010;58:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsang A, vonKorff M, Lee S, Alonso J, Karam E, Angermeyer MC. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain. 2008;9:883–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stanford EA, Chambers CT, Biesanz JC, Chen E. The frequency, trajectories and predictors of adolescent recurrent pain: a population based approach. Pain. 2008;138:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stinson JN, McGrath PJ. Measurement and assessment of pain in pediatric patients. In: Lynch ME, Craig KD, Peng PWH, editors. Clinical Pain Management: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Blackwell Science Inc; 2011. pp. 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lynch ME. The need for a Canadian pain strategy. Pain Res Manage. 2011;16:77–80. doi: 10.1155/2011/654651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGillion M, L'Allier PL, Arthur H, Watt-Watson J, Svorkdal N, Cosman T, Taenzer P, Nigam A, Malysh L. Recommendations for advancing the care of Canadians living with refractory angina pectoris: a Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:399–401. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70501-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips TJC, Cherry CL, Moss PJ, Rice ASC. Painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. Pain Clin Updates. 2010;XVIII:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G. Prevalence of undertreatment of cancer pain. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1985–91. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang N, Crane C. Suicidality in chronic pain: review of the prevalence, risk factors and psychological links. Psychol Med. 2006;36:575–86. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker CL, McDougall JJ. The cannabinomimetic arachidonyl-2-chloroethylamide (ACEA) acts on capsaicin-sensitive TRPV1 receptors but not cannabinoid receptors in rat joints. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:1361–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDougall JJ, Yu V, Thomson J. In vivo effect of CB2 receptor selective cannabinoids on the vasculature of normal and arthritic rat knee joints. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:358–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Notcutt W, Price M, Miller R, Newport S, Phillips C, Simmons S, Sansom C. Initial experiences with medicinal extracts of cannabis for chronic pain: results from 34 ‘N of 1’ studies. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:440–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]