Abstract

AIM

To explore the opinions of patient reporters to the UK Yellow Card Scheme (YCS) on the importance of the scheme.

METHODS

Postal questionnaires were distributed on our behalf to all patient reporters submitting a Yellow Card to the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA) between March and December 2008, with one follow-up reminder to non-responders. Qualitative analysis was undertaken of responses to an open question asking why respondents felt patient reporting was important. This was followed up by telephone interviews with a purposive sample of selected respondents.

RESULTS

There were 1362 evaluable questionnaires returned from 2008 distributed (68%) and 1238 (91%) respondents provided a total of 1802 comments. Twenty-seven interviews were conducted, which supported and expanded the views expressed in the questionnaire. Four main themes emerged, indicating views that the YCS was of importance to pharmacovigilance in general, manufacturers and licensing authorities, patients and the public and health professionals. Reporters viewed the YCS as an important opportunity to describe their experiences for the benefit of others and to contribute to pharmacovigilance. The scheme's independence from health professionals was regarded as important, in part to provide the patient perspective to manufacturers and regulators, but also because of dismissive attitudes and under-reporting by health professionals.

CONCLUSION

Direct patient reporting through the YCS is viewed as important by those who have used the scheme, in order to provide the patient experience for the benefit of pharmacovigilance, as an independent perspective from those of health professionals.

Keywords: adverse drug reactions, direct patient reporting, pharmacovigilance

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Little is known about why patients actually report suspected adverse drug reactions to schemes like the Yellow Card Scheme. Greater understanding of the reasons for reporting could be of benefit in marketing strategies aiming to increase the number of reports.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Direct patient reporting through the Yellow Card Scheme is viewed as important by those who have used the scheme, in order to provide the patient experience for the benefit of pharmacovigilance, as an independent perspective from those of health professionals.

Reporters viewed the Yellow Card Scheme as an important opportunity to describe their experiences for the benefit of others and to contribute to pharmacovigilance.

The Yellow Card Scheme's independence from health professionals was regarded as important, in part to provide the patient perspective to manufacturers and regulators, but also because of dismissive attitudes and under-reporting by health professionals.

Introduction

Spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) is an important method of pharmacovigilance which, in the UK, is achieved through the Yellow Card Scheme (YCS) and operated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Direct reporting of suspected ADRs by patients, well established in other countries, was called for in 2001 by the UK Consumer's Association [1], although a subsequent review indicated that there was insufficient evidence to support this [2]. A later review in 2007 concluded that patient reporting had more potential benefits than drawbacks [3]. The MHRA introduced patient reporting initially as a pilot in 2005 and now patients can report online, by telephone or by completion of paper forms available from general practitioner (GP) surgeries and pharmacies.

Little is known about why patients actually report suspected ADRs to schemes like the YCS. Greater understanding of the reasons for reporting could be of benefit in marketing strategies aiming to increase the number of reports. One of the main reasons given for advocating direct patient reporting [1] was that suspected ADRs reported to GPs were not then passed on to the regulatory authority, or even recorded in medical records [4, 5], which may be considered an incentive to report. Evidence from the Netherlands patient reporting scheme also showed that patients report a suspected ADR when they consider that a health professional has not paid attention to their concerns [6]. A report by Health Action International stated that patients provide much more detail and clearer descriptions of their experiences than health professionals when reporting suspected ADRs [7], indicating a desire to explain their experiences. A recent study from the Netherlands [8, 9] has also explored patients' motives and opinions about the reporting of suspected ADRs through qualitative interviews and a questionnaire sent to patient reporters. The main motives for patients in the Netherland's study to report suspected ADRs to a national pharmacovigilance centre were the severity of the suspected ADR and the need to share experiences.

A large evaluation of the UK YCS was completed in 2010. Part of this evaluation was designed to obtain detailed feedback from users of this scheme. This included reasons for reporting and overall opinions about reporting, which are published elsewhere [10]. The aim of this paper is to explore reporters' opinions about the importance of being able to report suspected ADRs through the YCS.

Methods

This paper describes qualitative findings from two phases of a large multiphase study evaluating patient reporting through the YCS. Approval was obtained from Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee for the study.

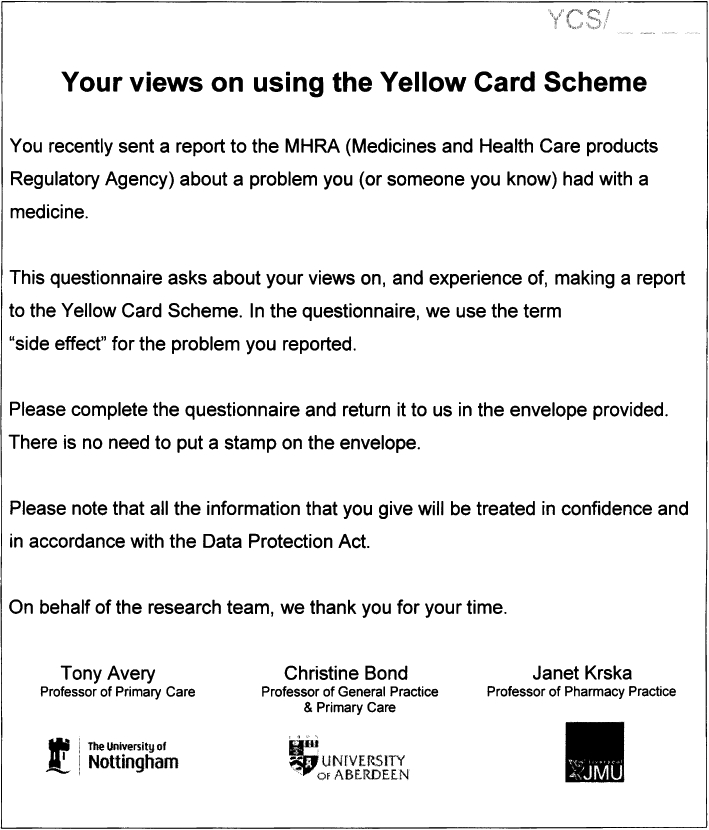

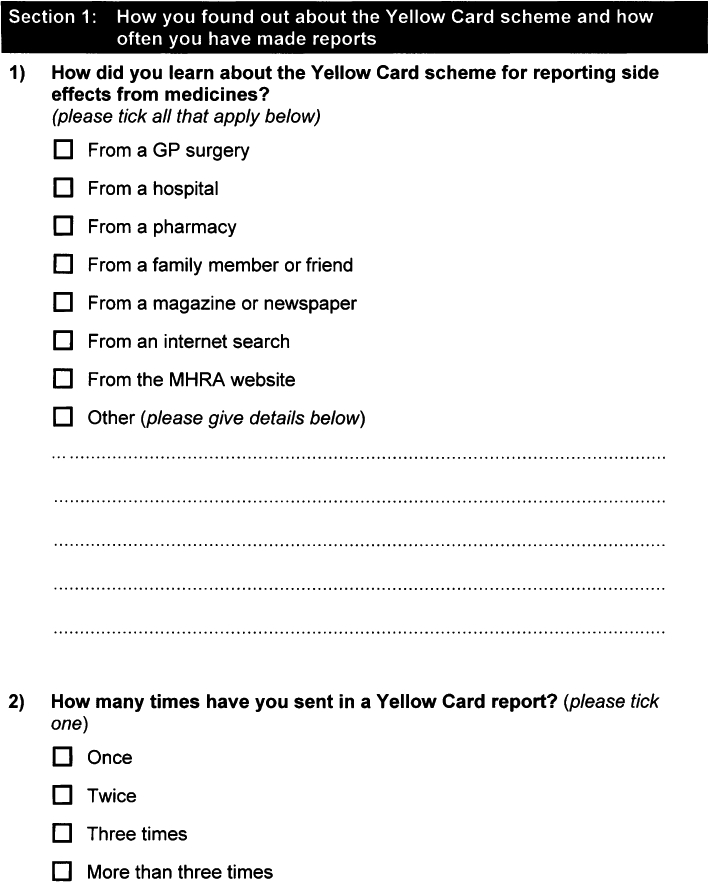

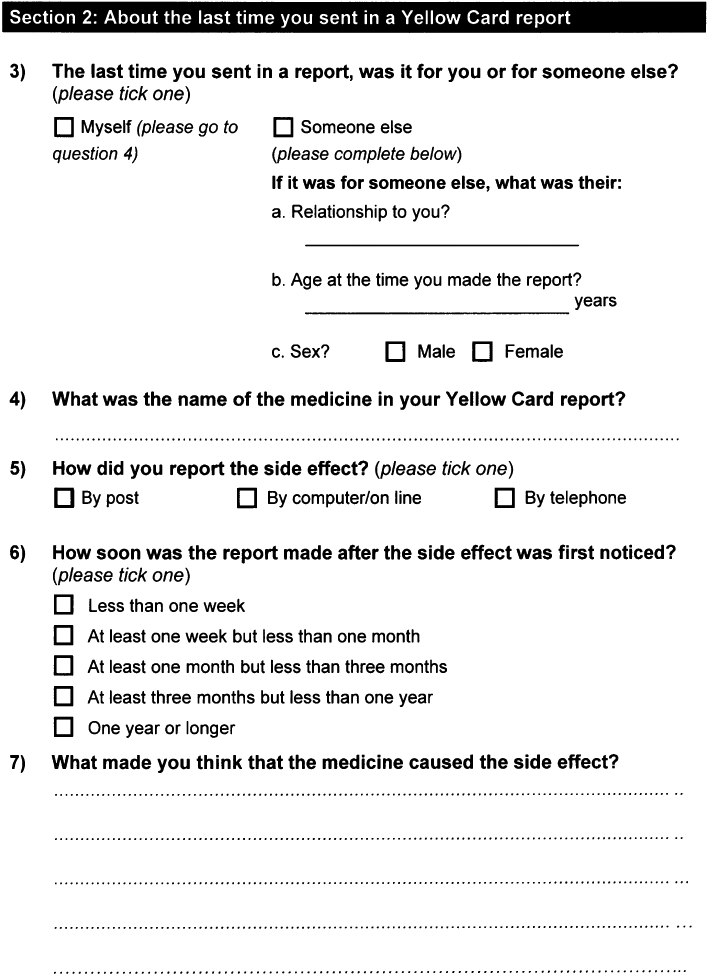

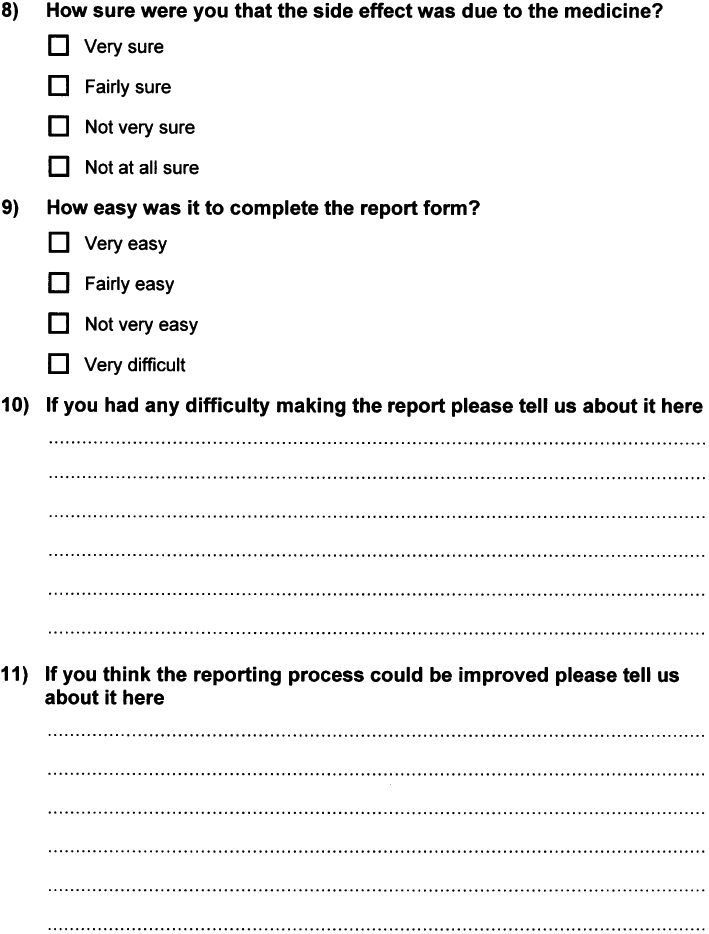

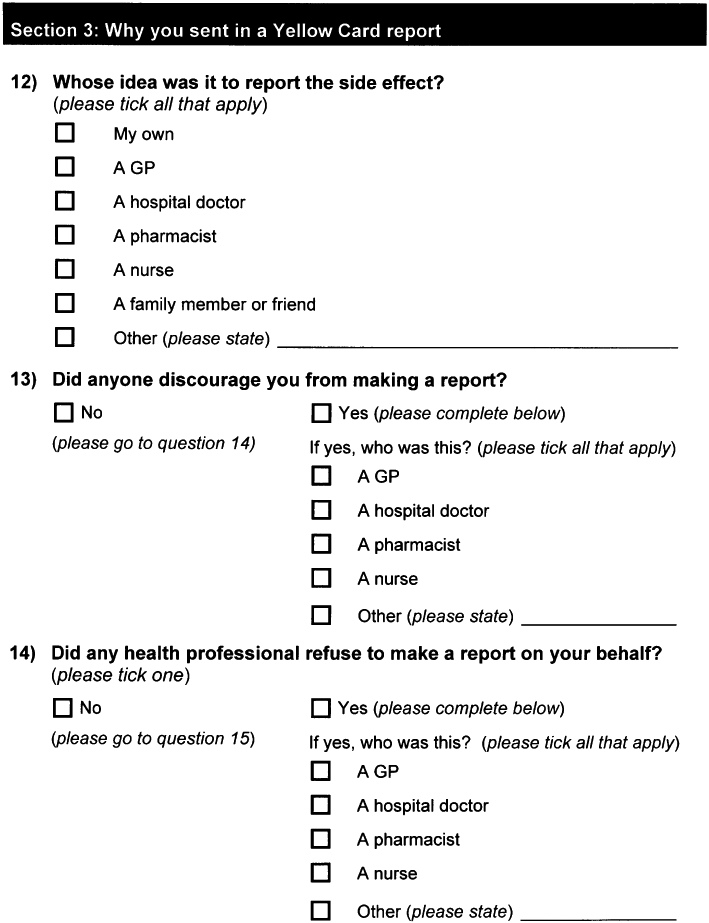

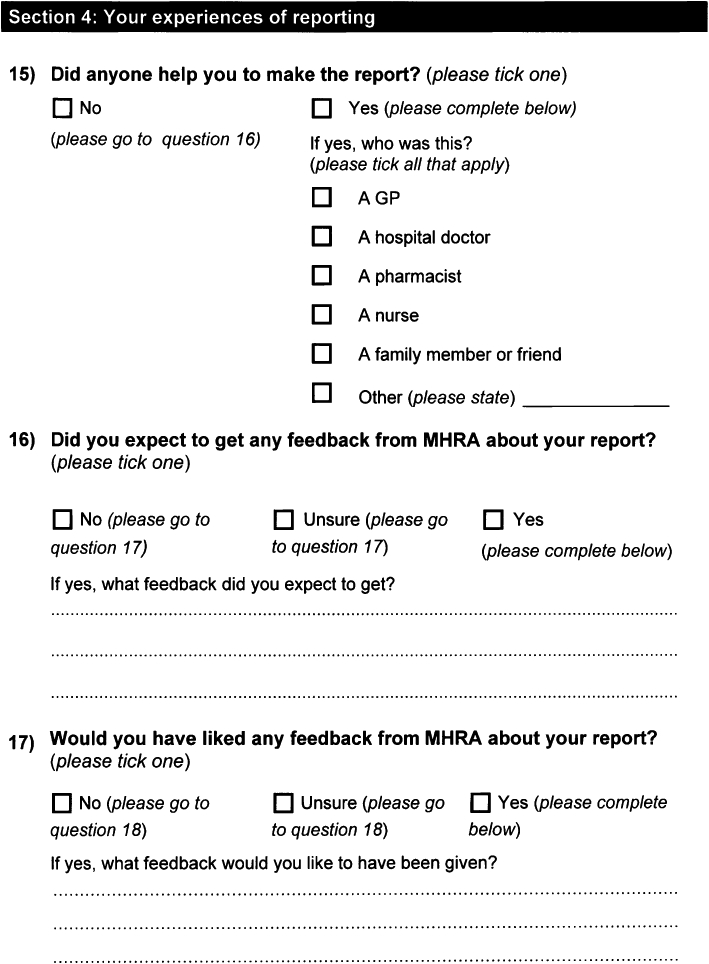

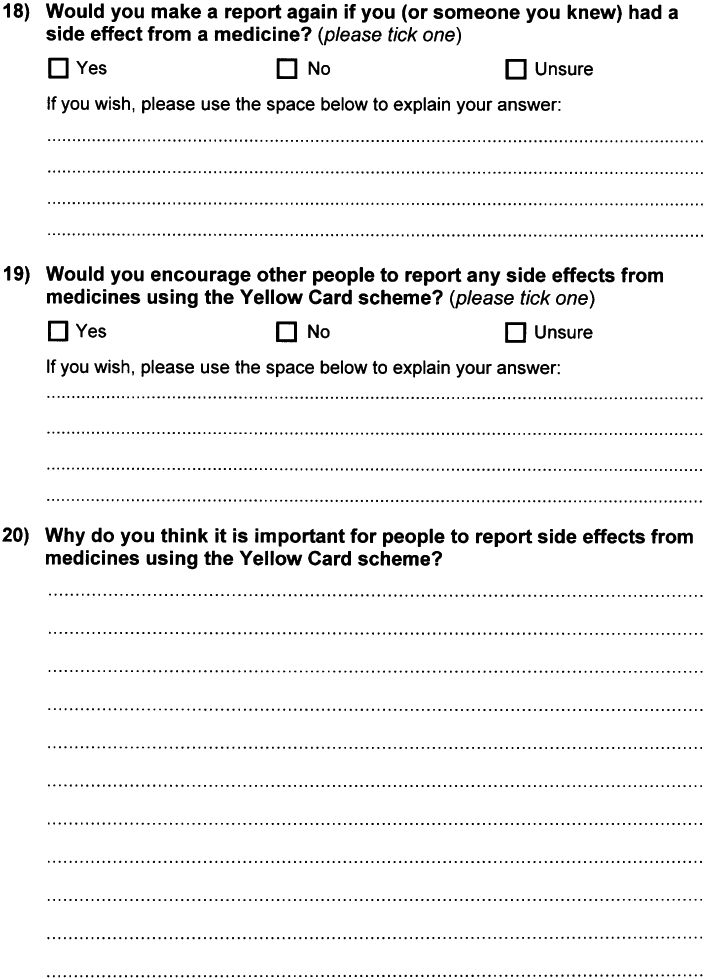

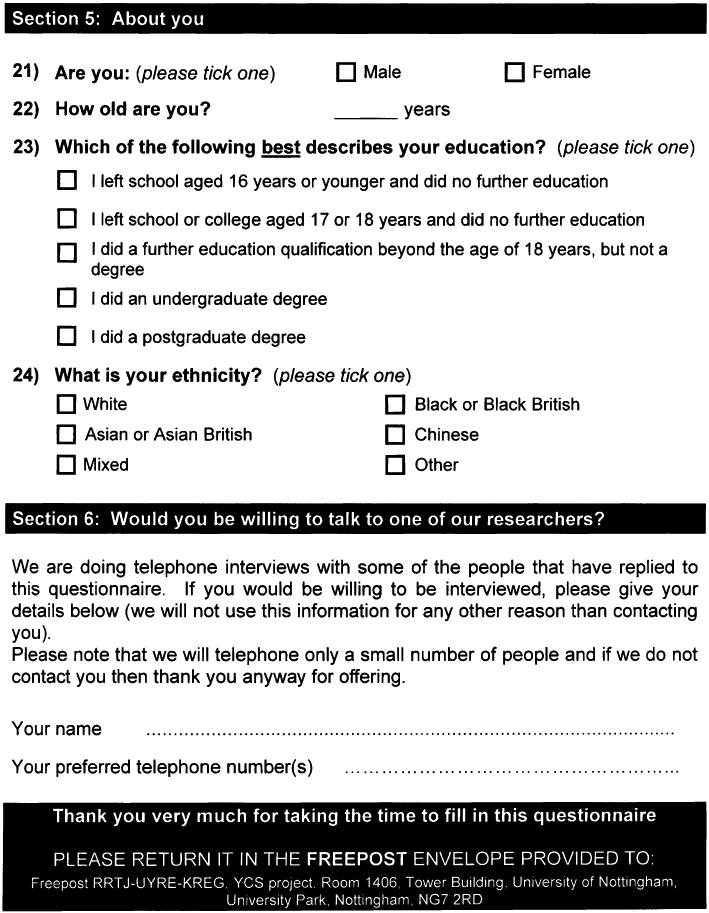

Phase 1 involved postal questionnaires which were distributed by the MHRA on our behalf to all members of the public who submitted a Yellow Card between March and December 2008 (see Appendix 1). This paper reports responses to an open question: ‘Why do you think it is important for patients to be able to report ADRs?’ Questionnaires included an invitation to provide contact details to participate in a telephone interview from which a sample was purposively selected for phase 2. The factors taken into account in the sampling included age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment of reporters and the reporting method. The semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted following the receipt of the questionnaire, using an interview guide developed by the research team (see Appendix 2). The development of the guide will be informed by the preliminary analysis of the first tranche of questionnaire data and a number of foreshadowed issues identified by the project team. Open questions in both the questionnaire and interview asked reporters to explain why they thought direct patient reporting was important and their reasons for reporting.

Data analysis: questionnaires

Data from the questionnaire responses were analysed using Excel. Initially, these were sorted to exclude all comments containing no actual data (e.g. no comment, none) and those which provided no actual response to the specific question (e.g. see earlier comment). Two researchers then independently read and categorized 100 different responses to identify possible fields. These were discussed; similar fields and those with very small numbers of responses were merged where appropriate, to minimize the number of fields. Final fields were agreed, then the two researchers independently categorized each response, using multiple fields as needed for each individual comment. The results were compared, all discrepancies discussed and final categories for each comment agreed. Overarching themes were then identified to incorporate all the fields.

Data analysis: telephone interviews

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with a theoretical sample of patients purposively selected from those who had completed questionnaires and had indicated a willingness to be approached for a telephone interview. We aimed to interview around 30 people in order to gain a wide range of opinions and maximum variation sampling was used to do this in order to obtain a wide range of opinions. Factors that were taken into account in the sampling included age, gender, educational attainment of patients and the mode of reporting. In addition, we selected some patients based on issues raised in the questionnaire, such as the perceived ease of reporting. An iterative process was applied as we conducted the interviews to try to ensure that we interviewed people with different perspectives based upon the preliminary analysis and emergent themes. We covered the following broad areas: exploration of any difficulties in making Yellow Card reports and suggestions for improvement in the reporting system, patients' motivations for making the report and anticipated contribution of their report, patients' expectations about what would happen to their report, patients' satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the process of making a report and patients' willingness to report in future.

The areas to be explored were reviewed and revised in the light of the data obtained from the initial interviews to ensure that the data obtained were relevant to the focus of the research. Interviews were audio-recorded digitally, with consent, and transcribed verbatim. The interview transcripts were analysed manually by an academic member of the research team and the analysis checked by another academic. Data were analysed for both anticipated (based on the questions asked) and emergent themes, using the constant comparison method. The researcher first read the interviews and noted the main themes. The data were then categorized into the major themes which were: finding out about reporting, recognition of adverse effects, reason for reporting, involvement of others in decision to report, how patient reports might differ from health professional reports, ease of reporting, what people expected to happen following making their report, advertising the scheme and reporting again and encouraging others to report. The researcher then identified from the data a number of subcategories for each of these themes.

Quotes are used to illustrate the themes and for each quote the following information is provided: whether the quote is from an interview or the questionnaire, interview/questionnaire number, gender and age (years) of reporter and mode of reporting, for example (Interview 12 – female, 54, paper).

Results

The MHRA posted the questionnaire to a total of 2008 patient reporters, of whom 1362 (68%) returned completed questionnaires and 27 telephone interviews were conducted. Demographic characteristics of respondents and interviews are shown in Table 1. Other results from the questionnaire have been reported elsewhere [8].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of questionnaire respondents and interviewees

| Characteristic | Questionnaire respondents | Interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 1362 | 27 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 447 | 8 |

| Female | 910 | 19 |

| Not stated | 5 | 0 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Left school at 16 years or younger | 309 | 7 |

| Left school at 17 or 18 years | 90 | 1 |

| Completed further education | 465 | 9 |

| Graduate | 277 | 3 |

| Postgraduate | 181 | 3 |

| Not known | 40 | 4 |

A total of 1238 respondents (90.9%) provided free text comments to the question: ‘Why do you think it is important for patients to be able to report ADRs?’, many presenting multiple views. There were a total of 1802 specific comments, of which 103 were judged to be unrelated to the question. Four main themes emerged, indicating views that the YCS was of importance to pharmacovigilance in general, manufacturers, patients and the public and health professionals. From the interview data, under the major theme of ‘reasons for reporting’ a number of subcategories emerged including altruism, solidarity and pharmacovigilance. The data from both sources have been combined below.

Importance for pharmacovigilance in general

The view most frequently expressed by questionnaire respondents (355), illustrated an awareness of the purpose of the scheme as a means of gathering data from a large population taking medicines. Interviewee data confirmed that reporters understood the pharmacovigilance process and had submitted reports through the YCS to help with this.

‘Because I feel it's important that medicines and their side effects are monitored. If people who suffer the side effects report them, it's the only way the MHRA will be made aware of the problems and effects some people are experiencing from certain medications.’ (Questionnaire – female, 34, further educational qualification).

‘One episode means little. Cumulative episodes/evidence could lead to improvement or withdrawal of medicines.’ (Questionnaire – male, 62, left school at 17 or 18).

‘It is vital to collate and monitor how drugs affect patients to help improve the efficacy of medicines and reduce mishaps and harm from wrong dose levels or by identifying patient groups who are particularly vulnerable. The drug companies do trials before medicines come onto the market but there needs to be continuous surveillance too.’ (Questionnaire – female, 57, graduate).

‘Mainly I hoped that it would, as I say, when the doctors look in the symptoms book in the future that if somebody came to them with similar side effects that we were having that they could actually see it straightaway because I think sometimes if it's something that's not in the book they just completely dismiss what you're saying.’ (Interview 13 – female, 32 years, Internet)

Importance for manufacturers and licensing

A number of comments related to making MHRA or manufacturers aware of ADRs (100), while other respondents expressed the hope that medicines may be improved or the information leaflets amended (173). A minority (41) indicated that it may be necessary to withdraw medicines in some cases as a result of data gathering. Some comments related to the need for research data on medicines, while others hoped that by drawing attention to problems, novel research would be initiated.

‘If a number of people report side effects, this might force manufacturers to include these on accompanying leaflet’ (Questionnaire – female, 65, postgraduate).

‘Because too many doctors prescribe inappropriately bowing to pressure from reps, patients and health authorities. In addition, a number of pharma companies tend not to look for AE data and so medicines are licensed on the basis of too small a safety database. “Real life” experience is the only way to build the database.’ (Questionnaire – male, 49, postgraduate).

This was expanded upon in the telephone interviews:

‘Then I expected them to collect them and if there were more than a certain number of people report the side effect then it would get flagged up as a common one in the NHS or, I don't know whether anything actually goes back to the manufacturers or if there are any studies that might come out of, you know, even if there might be something new that might put up a red flag, they might think well maybe we should look at this and find out what's happening there and instigate some further research. That would be my hope, but I tend to think that once something's licensed and they're making money then they're not really interested in going back and doing further research …’ (Interview – female, 43, further educational qualification).

Importance for patients and the public

Many questionnaire respondents expressed altruistic views indicating the need to make the public or other patients aware of side effects from medicines (152) and also to prevent others from suffering similar problems (165). A small number (8) felt it was a duty to report.

‘By reporting side effects, it will probably help other people in the future. If the side effect is written down on the medicine, you can read then make up your own mind to take it or not.’ (Questionnaire – female, 37 further educational qualification).

‘I just thought he'd been in so much pain and I felt so frustrated because no-one had listened or no-one seemed to consider that it could be that and I just thought well it's got to be logged for future because no doubt someone else in the country or the world will probably experience the same thing and … But I just thought, no I don't want to see, or don't want anyone else to be suffering like he did when there's no need because if someone's made aware of it then I just think it's better to make sure that everyone is aware so if it does happen.’ (Interview – female, 32, left school at 16).

‘Well I would really expect it to be sort of 50/50 as far as responsibility goes. Yes I do think that the GP or the pharmacist or whoever might just have a duty of care to report side effects like this in all instances. I also think that the people who, i.e. myself, who are swallowing all these nasty concoctions have got a duty to report back any untoward effects as well.’ (Interview – female, 54, further educational qualification).

Some interviewees were keen to find out if other people had experienced the same thing and to find other people with the same problem. There was a strong sense that these patients had a different motive in reporting to that of others and wanted something back. Although some of these expectations were unrealistic, people wanted to be reassured that they were not the only one who had suffered and wished to know how to alleviate their problem.

‘… thought well the reaction to this thing was so upsetting … that I felt perhaps it was worth sending it off just in case other people had experienced the same sort of thing … I had felt so unwell taking it that I just felt it justified giving a report. A degree of curiosity to know whether was I being neurotic or was it something that other people have experienced.’ (Interview – female, 75, further educational qualification).

‘Well I just wanted, I felt as though it could be another outlet for easing this problem and also if other people had had the same problems they might have reported it and somebody somewhere might know what I can do to alleviate the problem.’ (Interview – male, 66, left school at 16).

This was not mentioned by questionnaire respondents in response to the question on importance of the availability of reporting scheme. However, other responses indicated that a small minority did appear to have similar unrealistic expectations [8].

The importance of highlighting the patient's perspective on suspected ADRs, particularly their severity and impact, was raised by 90 questionnaire respondents and several interviewees. Some mentioned the unexpected occurrence of a reaction to a widely used medicine, while others indicated that side effects may be worse than the underlying medical problem.

‘If you are dependent on life sustaining drugs, there needs to be constant monitoring not just of short term effects and this seems a positive step forwards. Actually, no one knows better than the patient how it feels.’ (Questionnaire – female, 65, further educational qualification).

‘To make people aware of side effect of drug, although this was listed as a side effect. I feel my life has been seriously affected by this drug. I had to take a month off work and I am still in pain.’ (Questionnaire – female, 69, further educational qualification).

‘It was only when I actually came home and read up about Stevens Johnson syndrome that I realized how bad it was. I mean at the time they said it was serious and they said it was a very, very rare reaction, like one in a million but it was only when I came home and read up about it and I saw this like for reporting a side effect of a er drug. And I thought well penicillin is like the most commonest thing you get given isn't it.’ (Interview – female, 30, reporting for daughter age 5, educational status missing).

Respondents indicated that the severity or importance of symptoms may be perceived differently by patients and that patient reports might differ from those of health professionals, perhaps compensating for the latter's short-comings.

‘What doctors and nurses regard as a side effect worth reporting may differ from what the patient thinks. My mother has had a life changing experience that came ‘out of the blue’ and is keen to ensure others don't experience the same problem.’ (Questionnaire – female, 57, postgraduate).

‘I think by the time it's filtered through, through various other people it doesn't actually go in the form in which the patient actually reports it … to, to make mine fairly specific erm and it was fairly specific and quite, and fairly detailed but I'm sure that anybody else would simply, a lot of health professionals would simply specify some general adverse symptoms and that would be it.’ (Interview – female, 69, graduate).

‘I think it is important that people do get the opportunity to report their own understanding of a problem which may be different from a professional's understanding of a problem.’ (Interview – female, 57, further educational qualification).

The view was expressed that there is a need for a reporting mechanism which is independent of health professionals (32) and for patients' voices to be heard (49).

‘It monitors individual's experience irrespective of health professionals' expectations re: drug usage. My GP said the medicine had no link to the difficulties I experienced and took no notice of my experience. This system bypasses professionals' prejudices.’ (Questionnaire – female, 43, graduate).

‘I think it's far better than reporting it to your GP because, you know, you have more time to sit and think about it and it doesn't get filtered in the process if you know what I mean, you know what actually happened because you get so little time with the GP, you wouldn't have time to think it through and put all the exact details down.’ (Interview – male, 61, further educational qualification).

Importance for health professionals

The view that health professionals need to be informed about ADRs and perhaps to change their practice was raised by 167 questionnaire respondents. Some (79) also criticized Government incentives to prescribe some drugs or expressed distrust in the pharmaceutical industry.

‘I think it is too easy for health care professionals to go for the ‘quick fix’ if they know that a particular medication will ease a problem, but they don't follow up often on repeat prescriptions and don't really view subsequent problems holistically so can miss links to other reported problems. I see older people in relation to my work, they often have repeat prescriptions with many items on and some items are to deal with side effects of other meds. GPs don't have time to follow through. I think we, as patients, should do more to raise awareness of these issues.’ (Questionnaire – female, 53, further educational qualification).

‘Absolutely necessary to act as backup to clinical trials, plus acting as a brake on Government instructions to issue pills on a one-size-fits-all basis i.e. how many blood pressure and cholesterol tablets are issued to borderline cases in order to meet targets and gain bonuses?’ (Questionnaire – male, 72, left school at 16).

The issue of dismissive attitudes among healthcare professionals and their failure to report ADRs was raised by 106 questionnaire respondents.

‘Because I feel if I told my doctor about my side effect, he would belittle it and I would wrongly feel I was making too much of a fuss, whereas the reality of my experience of the side effect was not wrong or little. I feel scared of my GP's response. Being able to report side effects effectively anonymously allows side effects to be known by pharmacologists, which would otherwise remain unreported or lost in a GP's database somewhere.’ (Questionnaire – female, 43, graduate).

‘If I hadn't reported via the Yellow Card, I doubt if the GP or any hospital doctor would do so. They seem to have negative/passive attitudes. One stated if it wasn't already known to be a side effect, then it shouldn't be reported! My GP told me to look on the Internet to find out about side effects and alternative medication!!’ (Questionnaire – female, 69, postgraduate).

This was also raised in the interviews, with some expressing their concerns that GP reports may not always be accurate, that doctors may not even consider suspected ADRs.

‘Well I think very often doctors are very blinkered aren't they, I mean you go with these symptoms and they'll look at things like the age of the person or they'll look at me and think, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah you're, she must have a hormone imbalance’. Not look at what has happened in the past 2months that is different, so what has happened is ‘Oh she's on a new drug’ but they couldn't do that. Because I think GPs and hospital doctors, they seem to be very blinkered in their approach to problems that patients have.’ (Interview – male, 72, further educational qualification).

Some comments from questionnaire respondents indicated a lack of awareness among health professionals about patient reporting. This was confirmed by one interviewee who had previously submitted a Yellow Card and asked her GP for a report, but was given a healthcare professional reporting form:

‘Well the GP who, yes I did because I had to go into the surgery to ask for a new card, and the staff couldn't find one and they had to go and look in one of the GP's desks and found one in there, in one of the consult’ the GP consulting rooms er so this particular one was filled in on a GP yellow card rather than the normal patient's one. … and I added, I think I found it too small a sheet and I added a separate page.’ (Interview – female, 69, graduate).

Conversely, some reporters learned about direct reporting and were encouraged to submit reports by a pharmacist:

‘Unless patients are regular attenders with a GP or hospital consultant, there may not be an opportunity to mention any possible related side effects. In my case, I did mention my concerns briefly to a consultant in a ‘one off’ consultation, who rather dismissed it out of hand. I could not say he refused to report, but he did not seem to be aware of the adverse side effects mentioned in the leaflet. It was the pharmacist who felt it was a serious concern which should be reported via the Yellow Card Scheme.’ (Questionnaire – female, other data missing).

Discussion

Reporters to the YCS clearly felt that it provided them with an opportunity to describe their experiences for the benefit of others and to contribute to pharmacovigilance for the greater good. Only a minority viewed the reporting scheme as an opportunity for personal gain, with the large majority showing a good understanding of the pharmacovigilance process.

The ultimate potential benefits of the scheme for patients was recognized as making patients be aware of possible ADRs, through the patient information leaflet or advice from health professionals, thus helping them make informed choices about whether or not to use medicines.

The patient reporting scheme's independence from health professionals was viewed as a positive benefit and a significant proportion of respondents indicated dismissive attitudes and less than ideal practices of health professionals as a reason for patients to report directly. The view was also expressed that patient experiences may be filtered by health professionals and that it was important for regulators to learn about their experiences ‘from the horse's mouth’. This was derived from the opinion that patient reports would be different and more complete than healthcare professional reports, thus supporting arguments made in the literature [7–9, 11]. Although one US study [12] on reports to the FDA found that patients' reports were only more complete for behavioural aspects, many of our respondents suggested that patient reports would show a better understanding of the effect of the ADR on a patient's life and that a healthcare professional report might just consist of a list of symptoms. This supports Basch's thesis that patient self-reports of suspected ADRs provide valuable information and capture the subjective elements of patient experiences [13].

Strengths and limitations

This study triangulates data from two phases of a larger study, the overall results of which indicate that patient reporting adds value to pharmacovigilance [14]. The questionnaire data were derived from a substantial proportion of all reporters to the YCS during the period of study, most of whom responded to the specific question concerning the importance of patient reporting. The interviews provided further opportunity for a purposive sample of reporters to describe their opinions without the constraint of limited space on the questionnaire. However, we acknowledge that reporters to the YCS constitute a minority of the population who may experience ADRs and respondents to our questionnaire were further self-selected.

Importance for practice and policy

The potential benefits of patient reporting, as summarized at the First International Conference on Consumer Reports on Medicines in 2000, included the promotion of consumer rights and equity, acknowledging that consumers have unique perspectives and experiences and that healthcare organizations would benefit from consumer involvement [15]. Our data lend support to the view that patient experiences are important, from their perspective, rather than from that of the regulator. The results, like those from the Netherlands [8, 9], also indicate that reporters' motivations are often altruistic, seeking to benefit other medicine users. An emphasis on the benefits of reporting to other medicine users could be used to motivate further reporting from other patients, particularly when marketing the scheme. Several studies have examined health professional's motivations for reporting suspected ADRs. Some of the motives for healthcare professional reporting are also important reasons for patients to report, such as severity of the suspected reaction and wanting to contribute to medical knowledge. Hasford et al. [16] and Ekman et al. [17] state that the main reasons that motivated health professionals to report were the severity of the reaction, if the reaction was unusual, the reaction of the reporter to the drug and if the reaction was caused by a new drug. Biriell et al. [18] reported that a desire to contribute to medical knowledge, a reaction previously unknown to the reporter, a reaction to a new drug, a desire to report all significant reactions, a known association between drug and the reaction and the severity of reaction motivated physician and pharmacists to make reports. Bäckström et al. [19] reported that three-quarters of respondents stated that the severity of their reaction was the main factor determining whether a suspected ADR was reported or not.

Currently, patient reports are combined with those of health professionals by the MHRA to add to pharmacovigilance processes. Little feedback is provided to patient reporters and there are no mechanisms for making patient experiences available for other patients and health professionals to learn from. Patient opinions of the regulator, their expectations about what happens to the information in their report, and how those expectations are handled, will be of great importance for sustaining patient interest in reporting, given its primarily altruistic nature.

The importance of the availability and independence of a patient reporting system is clear, given beliefs that health professionals do not report, filter reports, dismiss patients' views or do not consider ADRs during consultations [3, 20]. There was some evidence that patients were more likely to report suspected ADRs if they felt their health professional had not acknowledged their concerns. Dismissive attitudes among health professionals were identified as reasons for reporting in a pilot study evaluating the Netherlands patient reporting scheme [6]. However, more altruistic reasons for reporting were found in a subsequent larger study [8, 9]. Dismissive attitudes have also been seen in physicians in a small US study [21]. A more proactive approach to identifying suspected ADRs and acknowledgement of the patient experience could be of benefit for both patient and health professional reporting.

In conclusion, direct patient reporting through the Yellow Card Scheme is viewed as important by those who have used the scheme, in order to provide the patient experience for the benefit of pharmacovigilance as an independent perspective from those of health professionals.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) programme (project number RMO5/JH30) and will be published in full in Health Technology Assessment; 2011; 15(20). Visit the HTA programme website for further project information.

Appendix 1: Questionnaire

Appendix 2

Interview schedule for telephone interviews

The interviewer will set the scene regarding audio taping, confidentiality, etc.

Story of illness/event

Story of treatment

Story of suspected side effect

Story of decision to report

Story of process of reporting

Story of illness/event

You've all ready told us a little bit about the side effect that you have reported to the MHRA using the Yellow Card Scheme. I want to use this opportunity to get you tell me a bit more about the circumstances that lead up to you reporting.

Firstly can you tell me a little bit about how you came to take the medicine that caused the problem:

Reason for medicine (symptoms, etc.) and how you came to take it

Prescribed or OTC

How long had you been taking the medicine before you realized there was a problem

Tell us about the side effect. Description of symptoms, etc.

What was the problem?

Did you stop taking the medicine?

Straight away? If you didn't stop why not?

What made you think the symptoms were related to medicine, how certain were you, did you talk to anyone about it if so who? what did they say?

Was this the first time you have ever experienced a side effect from a medicine you have taken?

On this particular occasion, how easy did you find it to link the particular side effect you experienced to taking a particular medicine?

Story of decision to report

Can you tell me a bit more about what made you decide to report this side effect using the Yellow Card Scheme?

When you experienced [the suspected side effect] did you discuss this with anyone?

If so what advice did they give you?

Were you aware of the Yellow Card Scheme and/or the fact that patients can report before you recently experienced [the suspected side effect]?

How did you know about the Yellow Card scheme?

What made you decide to use paper/internet reporting?

How easy did you find the reporting process you used (i.e. questionnaire or internet)?

Did you experience any specific difficulties in using this process?

How easy did you find it to describe the side effects you had experienced?

Were you able to provide all the information that the report form asked you for?

How much time did it take you to fill in the form?

Did you need additional help in completing the form?

If so, from whom did you get this help?

Were you contacted following your report?

What was the nature of the contact?

Was this what you were expecting? What else were you expecting, if anything?

Would you have liked to have had any further contact? If so what would you have liked?

Until recently, reports to the Yellow Card Scheme could only be made by professionals such as doctors, nurses and pharmacists. Do you think it's a good idea to expand the scheme so that patients are now able to report side effects of medicines?

-

Which do you think is likely to be more useful – when patients make the reports to the scheme or when health professionals such as doctors, pharmacists and nurses do?

What makes you say that?

What do you think is the advantage of each?

-

What do you think is the point of reporting side effects?

Who do you think will benefit? Health care professionals and/or patients?

In what way(s) might they benefit?

Do you think the reporting system could be improved in any way?

Having made this report, would you consider reporting again if you experienced side effects from another medicine?

Would you encourage others to fill in a report if they experience a side effect from a medicine?

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. UK call for patient adverse drug reaction reporting. Scriptorium. 2001;2634:4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Grootheest K, de Graaf L, de Jong-van den Berg L. Consumer adverse drug reaction reporting: a new step in pharmacovigilance? Drug Saf. 2003;26:211–7. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200326040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blenkinsopp A, Wilkie P, Wang M, Routledge PA. Patient reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions: a review of published literature and international experience. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:148–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarernsiripornkul N, Krska J, Richards RME, Capps PAG. Pharmacist-assisted patient reporting of adverse drug reactions. Pharm J. 1998;261:R33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarernsiripornkul N, Krska J, Capps PAG, Richards RME, Lee A. Patient reporting of potential adverse drug reactions: a methodological study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:318–25. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Grootheest AC, de Jong-van den Berg L. Review: patients' role in reporting adverse drug reactions. Exp Opin Drug Saf. 2004;3:363–8. doi: 10.1517/14740338.3.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herxheimer A, Crombag R, Alves TL. Adverse Drug Reactions: A Fifteen-Country Survey & Literature Review. Health Action International Europe, May 2010. Available at http://www.haiweb.org/10052010/10_May_2010_Report_Direct_Patient_Reporting_of_ADRs.pdf (last accessed 11 May 2011)

- 8.van Hunsel F, van der Welle C, Passier A, van Puijenbroek E, van Grootheest K. Motives for reporting adverse drug reactions by patient-reporters in the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:1143–50. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0865-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Hunsel FP, ten Berge EA, Borgsteede SD, van Grootheest K. What motivates patients to report an adverse drug reaction? Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:936–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLernon D, Bind C, Lee A, Watson M, Hannaford P, Fortnum H, Krska J, Anderson C, Murphy E, Avery A on behalf of the Yellow Card Study Collaboration Patient views and experiences of making adverse drug reaction reports to the Yellow Card Scheme in the UK. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:523–31. doi: 10.1002/pds.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medawar C, Herxheimer A. A comparison of adverse drug reaction reports from professionals and users, relating to risk of dependence and suicidal behaviour with paroxetine. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2003;15:5–19. /2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alshammari TM, Rizwanuddin Ahmad S, Swartz L, Hammad TA. Comparison of adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports submitted to the FDA by consumers and healthcare professionals (HCPs) Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:S1–273. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:865–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avery AJ, Anderson C, Bond CM, Fortnum H, Gifford A, Hannaford PC, Hazell L, Krska J, Lee AJ, Mclernon DJ, Murphy E, Shakir S, Watson M. Evaluation of patient reporting of adverse drug reactions to the UK ‘Yellow Card Scheme’: literature review, descriptive and qualitative analyses, and questionnaire surveys. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:1–234. doi: 10.3310/hta15200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organisation. Consumer reporting of adverse drug reactions. WHO Drug Inf. 2000;14:211–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasford J, Goettler M, Munter KH, Müller-Oerlinghausen B. Physicians' knowledge and attitudes regarding the spontaneous reporting system for adverse drug reactions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:945–50. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekman E, Backstrom M. Attitudes among hospital physicians to the reporting of adverse drug reactions in Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:43–6. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biriell C, Edwards IR. Reasons for reporting adverse drug reactions–some thoughts based on an international review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1997;6:21–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1557(199701)6:1<21::AID-PDS259>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Backstrom M, Mjorndal T, Dahlqvist R, Nordkvist Olsson T. Attitudes to reporting adverse drug reactions in northern Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56:729–32. doi: 10.1007/s002280000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGuire T, Moses G. What do consumers contribute to pharmacovigilance ? Lessons from the AME line. Conference Proceedings, National Medicines Symposium, National Convention Centre, Canberra 7–9 June 2006. Available at http://www.icms.com.au/nms2006/abstract/132.htm (last accessed 11 May 2011)

- 21.Golomb BA, McGraw JJ, Evans MA, Dimsdale JE. Physician response to patient reports of adverse drug effects. Drug Saf. 2007;30:669–75. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730080-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]