Abstract

There have been numerous reviews written to date on estrogen receptor (ER), focusing on topics such as its role in the etiology of breast cancer, its mode of regulation, its role as a transcriptional activator and how to target it therapeutically, just to name a few. One reason for so much attention on this nuclear receptor is that it acts not only as a prognostic marker, but also as a target for therapy. However, a relatively undiscovered area in the literature regarding ER is how its activity in the presence and absence of ligand affects its role in proliferation and cell cycle transition. In this review, we provide a brief overview of ER signaling, ligand dependent and independent, genomic and non-genomic, and how these signaling events affect the role of ER in the mammalian cell cycle.

Keywords: Cell cycle, estradiol, estrogen receptors

INTRODUCTION

The human estrogen receptor (ER) is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor family, requiring activation by association with 17-β-estradiol (E2) to perform its function as a transcription factor. Upon diffusion of E2 across the cell membrane, the hormone can bind to ER followed by receptor dimerization, interaction of ER dimers with the estrogen response elements (ERE) of target genes, recruitment of coregulatory factors, and initiation of target gene transcription.[1,2]

Two subtypes of ER have been identified to date: ERα and ERβ. These forms are differentially expressed in various tissues and have unique functions, but the functional domains of ER are common to both receptors.[1–8] The N-terminal A/B domain contains the activation function 1 (AF1) domain, which is involved in ligand-independent initiation of gene transcription.[2] The DNA-binding domain (DBD) of the ER protein is located in the C domain, enabling ER to associate with the EREs of target genes.[3] The D domain connects the E and C domains and is called the hinge region.[2] The E domain is the ligand-binding domain (LBD), which contains the AF2 domain; both are key for the initiation and activation of ER-target gene transcription.[2] The AF2 domain also contains binding cavities for coactivator and corepressor proteins.[3] Dimerization of ERα occurs after the binding of E2 to the LBD, followed by the phosphorylation of ERα and initiation of gene transcription.[4,5] Together with the other domains, the F domain of ER regulates ligand binding, coregulator protein interactions, and transcription activation events.[6]

Post-translational modifications of ER, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination, are important regulatory mechanisms.[8] Receptor phosphorylation can alter the conformation of ERα and expose the protein to further rounds of phosphorylation. Additionally, phosphorylation can activate transcription of target genes in response to specific phosphorylations or promote associations of ERα with coactivator proteins.[4 9–11] In response to estradiol binding, Ser118 is the predominant phosphorylation site on the ERα protein; however, Ser104 and Ser106 are also frequently phosphorylated sites.[12,13] ER phosphorylation can also occur in response to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, which promotes phosphorylation of Ser118 and Ser167 residues.[8,11] These common phosphorylation sites are located in the AF1 domain, and their phosphorylation promotes the recruitment of ERα coactivator proteins.[11]

ER SIGNALING

Classical signaling

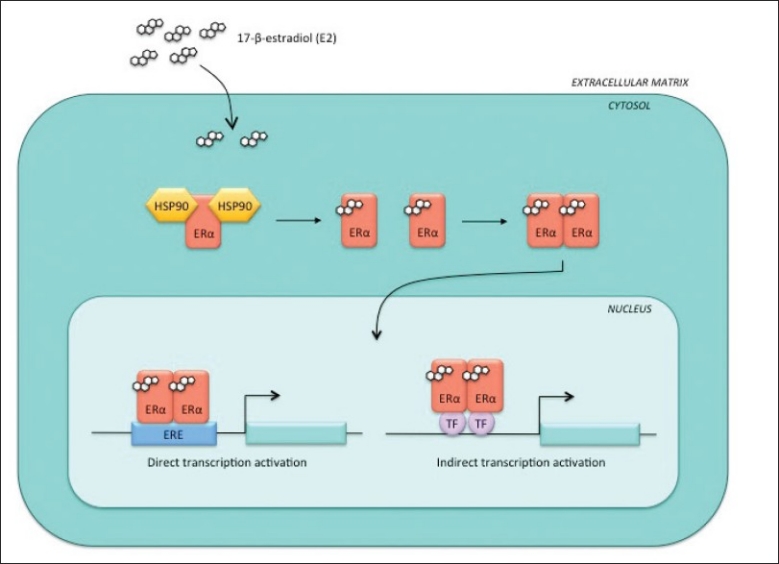

Unliganded ERα is bound to a 90-kDa heat shock protein (HSP90) in the cytoplasm, forming a large molecular complex[Figure 1].[14] Binding of molecular chaperones (e.g. HSP90) to a target protein (e.g. ERα) maintains proper protein folding in the cytoplasm, which is necessary for different intracellular processes such as stabilization of nascent polypeptide chains, prevention of protein aggregation, as well as chaperoning and transportation of the proteins across cellular membranes.[15,16] Dissociation of ERα from HSP90 occurs upon binding of the E2 ligand and causes a conformational change of ERα, allowing receptor homodimerization. These dimers can translocate into the nucleus and bind directly to the EREs of ER target genes, initiating gene transcription.[17] These events trigger an estrogenic (i.e. ligand-dependent) response in the cell, consisting of a threefold to fourfold increase in the level of ER phosphorylation upon treatment with estrogen as compared to unliganded conditions.[1,18]

Figure 1.

Estrogenic response. Upon the binding of estrogen (E2) to ERα, the receptor dissociates from the heat shock proteins in the cytoplasm and forms a homodimer, which can translocate to the nucleus. Once there, ERα homodimers can initiate transcription from the ERE sites of ERα target genes or through interactions with other transcription factors

Non-classical signaling

Ligand-bound ERα forms a complex with DNA-bound transcription factors, such as SP-1 and AP-1, activating the transcription of genes that do not contain a classical ERE [Figure 1].[19] Examples of non-ERE containing genes are the ovalbumin proximal promoter, collagenase and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1).[20–26] At these genes, ERα is recruited to AP-1 sites by Jun/Fos, making ERα part of the Jun/Fos coactivator complex, which initiates non-ERE transcriptional activation.[27]

Non-genomic signaling

The non-genomic functions of ERα are mediated in part via the plasma membrane-associated receptor, giving rise to intracellular signal transduction pathways and rapid cytoplasmic signaling [Figure 2].[28–31] Simoncini et al. showed an increase in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity due to an increase in physiological concentrations of E2 in human vascular endothelial cells.[32] Nitric oxide (NO), a pleiotropic regulator, is a product of eNOS and functions by regulating biological processes such as vasodilation, neurotransmission, and macrophage-mediated immunity. In cancer, NO has been shown to contribute to angiogenesis through the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and therefore promotes tumor growth.[33] Stimulation of NO release by E2 results in activation of eNOS by the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and MAPK pathways.[34]

Figure 2.

Non-genomic ERα pathway. Upon stimulation by growth factors, ERα is able to initiate cytoplasmic signaling cascades, such as the MAPK and PI3K pathways. ERα is phosphorylated in the non-genomic pathway by a tyrosine kinase receptor (TKR) in a ligand-independent manner and can promote unregulated gene transcription

ERα has been shown to bind to the p85α regulatory subunit of PI3K in a ligand-dependent manner, but activation of eNOS is completely blocked using wortmannin, a PI3K inhibitor, or ER antagonist ICI 182,780.[32,35] In this non-genomic pathway, ERα initiates a rapid, transient signaling cascade which originates from the cytoplasm via direct association with signal transduction proteins, including MAPK, protein kinase C (PKC), and guanosine triphosphate-binding proteins (G-proteins).[36,37] Treatment of human granulosa-luteal cells (hGLCs) with agents known to increase the levels of cyclic AMP resulted in downregulation of ERα levels. Additional studies using adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate (protein kinase A inhibitor), Rp-isomer, triethylammonium salt, and an adenylate cyclase inhibitor (SQ 22536) showed a modulation of ERα levels, suggesting a link between ERα and signal transduction pathways, such as those involving protein kinase A (PKA) or PKC.[38] Another example of the non-genomic action of ERα involves MAPK signaling. Treatment of MCF-7 cells with E2 results in the activation of MAPK, which is preceded by a rapid increase in cytosolic calcium. Subsequent treatment with E2 and ICI 182,780 abrogates the activation of MAPK.[39]

It has been suggested that cytoplasmic, plasma membrane-associated ERα is only a small subset of the classic ERα, or perhaps a spliced variant of full-length ERα.[40,41] Support for this hypothesis surfaced when a 46-kDa spliced variant of ERα (ERα46) was identified in human endothelial cells. Confocal microscopy revealed that a proportion of both full-length (ERα66) and ERα46 was localized outside of the nucleus and was capable of binding to E2; however, E2-mediated transcriptional activation by ERα46 was lower than observed for ERα66. Additionally, ERα46 could inhibit classical ERα66-mediated transcriptional activation.[41] In other studies, membrane ERα and intracellular ERα were found to be closely related, originating from the same coding sequence.[42–44] Using immunohistochemistry, Watson et al. found eight distinct antibodies against full-length ERα were able to recognize membrane-associated ERα, suggesting the membrane and nuclear ERα proteins are highly related.[44]

Ligand-independent signaling

Activation of ERα through a ligand-independent pathway is mediated by growth factor signaling, which results in the phosphorylation of ERα.[45,46] Such ligand-independent activation of ERα has been linked with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR) signaling.[47] EGFR signaling activates cytoplasmic nonreceptor kinases (e.g. Src) that can phosphorylate ERα, as well as some ERα coactivator proteins.[46] ERα binds to IGF-1R in response to E2 stimulation, forming a heterodimer; the downstream result is activation of MAPK signaling.[48] Kahlert et al. overexpressed ERα in COS7 and HEK293 cells, which have high levels of endogenous IGF-1R. Upon treatment of these cells with E2, ERα was found to bind to IGF-1R, resulting in rapid phosphorylation of IGF-1R and cytoplasmic extracellular signal-related kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2). These ERα-triggered events were required to induce the activation of an ER-responsive ERE-luciferase reporter in IGF-1-stimulated cells. These data demonstrate that binding of the E2 ligand to ERα is a necessary step toward rapid IGF-R1 cytoplasmic signaling.[48]

Another example of the ligand-independent signaling by ER involves its binding to G-proteins. G-protein-coupled ERα stimulated with E2 can initiate signal transduction from the plasma membrane through the transactivation of EGFR/IGFR followed by activation of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMP-2, MMP-9) and tyrosine kinase c-Src. MMP-2 and MMP-9 are type IV collagenase/gelatinase proteins, which degrade collagen in the mammalian extracellular matrix and facilitate cancer cell invasion through basement membranes.[49] c-Src can activate downstream signaling cascades, such as MAPK, PI3K, and PKC, through interactions with ion channels or membrane-associated G-protein signaling molecules and elicit physiological effects, including proliferation, metastasis, and survival.[50]

G-proteins and ERα are enriched in cavities of the plasma membrane called calveolae and are sites of protein interactions between G-proteins and ERα.[51] Other signaling molecules needed for the initiation of cytoplasmic cascades can also migrate to the calveolae.[50] Interactions of ERα with a G-protein in the calveolae can recruit c-Src, Shc (Src homology complex), and the p85α subunit of PI3K.[52,53] As a result of ERα activation, MMP-2 and MMP-9 can activate a multiple-kinase signaling cascade through transactivation of EGFR.[54] Additionally, c-Src, Shc, and p85α recruitment and activation result in the activation of secondary signaling messengers and downstream kinase pathways such as ERK, MAPK, and PDK1/AKT.[55–58]

ER IN NORMAL MAMMARY TISSUE

The estrous cycle

The female mammary gland is in a state of quiescence until puberty, at which point cell division increases substantially. The onset of puberty leads to observable estrous cycles of cell proliferation followed by involution in the female mammary gland.[59] The estrous cycle originates in the follicular phase followed by the luteal phase, which falls 1 week after ovulation and is the point at which breast epithelial cell proliferation is maximal in the adult breast. During the luteal phase, E2 and progesterone hormones are secreted through the corpus luteum, but only E2 levels are elevated during the follicular phase.[60–67]

Proliferation of human mammary tissue

Normal human breast tissue proliferation appears to be solely dependent on E2, with no obvious effects by progesterone.[68] To examine this specific role of E2, Laidlaw et al. subcutaneously implanted pieces of normal human breast tissue into athymic nude mice, with subsequent implantation of slow-release E2 and/or progesterone pellets. The rate of proliferation of the implanted tissues was assessed via thymidine uptake. The E2 pellet increased the thymidine labeling index from a median of 0.4% to 2.1% after 7 days, while the progesterone pellet had no effect.[69] Additional evidence for the importance of E2 in the maintenance of a healthy breast is that the risk of breast cancer increases with an increased duration of exposure to E2. More specifically, early onset of menarche and late menopause are both associated with a greater risk of cancer incidence.[70]

The proliferative stages of a normal breast are during puberty and the estrous cycle and, during these stages, the majority of proliferating cells do not express ER, or do so at a very low level in terminal end buds and ducts.[71] The level of differentiation of the mammary parenchyma determines the proliferative activity of the mammary epithelium.[70] In post-pubertal women, the lobule type 1 (Lob 1), also known as the terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU), is the most undifferentiated structure. Structures progress from Lob 1 to Lob 2, which has a more complex morphology and is more differentiated than Lob 1. Lob 1 and Lob 2 structures differentiate further to Lob 3 and Lob 4 structures during pregnancy, under the influence of hormones.[72] Upon the full differentiation to Lob 4 structures during pregnancy, the proliferative activity of the mammary epithelium is reduced.[59]

The ERα and progesterone receptor (PgR) content of the lobular structure is also directly proportional to the rate of cell proliferation. The ERα/PgR content of Lob 1 epithelial cells is much higher (14%) than that of Lob 3 cells (0.5%) due to the higher proliferative activity of cells in Lob 1 structures; this could explain the higher susceptibility of Lob 1 to transform and become the site of origin for ductal carcinomas.[73–75] Lob 1 contains at least three cell types, based on their ERα status and proliferative index as measure by Ki67 expression: A) ERα−/Ki67+, B) ERα+/Ki67−, and C) ERα+/Ki67+. Evaluation of ERα status in a tumor is critical to predict a response to endocrine therapy, while the antibody against Ki67 serves as a potent tool for evaluating proliferation status because the Ki67 nuclear antigen is only expressed in cycling cells, not those in G0.[76] The three cell types described are regulated by positive and negative feedback loops, which are mediated by estrogen signaling. For example, E2 stimulation of group B cells could release certain growth factors which, through paracrine pathways, can increase the proliferation of group A cells. However, there is some controversy regarding the potential for reversion of ERα-negative cells to ERα-positive cells.[69,77] To address this issue, a study was initiated to examine whether cellular expression of ERα occurs on a clonal basis or as a function of the differentiation process. MCF-7 cells were subjected to a soft agar colony formation assay in the presence or absence of tamoxifen, an antiestrogen, followed by immunoperoxidase staining with a monoclonal ERα antibody. This revealed heterogeneity in ERα expression among cells within the same, or different, clones. Additionally, tamoxifen was shown to significantly reduce clonal growth; proliferating clones unresponsive to tamoxifen had low ERα expression. Based on these results, some investigators propose that a change in ERα expression concomitantly occurs with the differentiation of cells within clones, suggesting that ERα-positive colonies may arise from ER-negative progenitors.[77]

There is also evidence to suggest that cellular proliferation can be independent of the ERα/PgR status of the cell. Knabbe et al. suggest that cells can control the proliferation of adjacent cells through autocrine or paracrine actions.[78–80] To this end, they co-cultured MCF-7 cells with MDA-MB-231 cells and discovered that secretion of biologically active transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) from MCF-7 cells inhibited proliferation of the MDA-MB-231 cells.[78–80]

40% of epithelial cells in pre-pubertal rats express ER in the nucleus, dropping to 30% upon the onset of puberty and to 5% by day 14 of pregnancy. However, there was a significant induction of the nuclear ER levels during lactation - up to 70% by day 21. Studies have shown that 90% of ERα-expressing cells are non-proliferative and 55-70% of proliferating cells express neither ERα nor ERα, showing that neither receptor is a prerequisite for estrogen-mediated proliferation.[81,82] Similarly, treatment of proliferating MCF-7 cells with any selective ER modulator (SERM, i.e. tamoxifen) results in an increase in ERα levels. Consequently, p27 levels increased, which is a mark of non-proliferative cells.[82] Together, these studies in normal mammary glands highlight the paradoxical role ER has in cellular proliferation.

Unlike normal mammary epithelial cells containing ER/PgR, estrogens stimulate the proliferation of human preadipocytes, resulting in induction of c-myc and cyclin D1 expression; this suggests that c-myc and cyclin D1 may be mediators of estrogen-stimulated proliferation in preadipocytes.[83] These proliferating preadipocytes are often located in proximity to non-dividing cells that express ER/PgR. ER and PgR-positive cells can stimulate proliferation in adjacent ER/PgR cells via paracrine signals, such as E2-induced genes: PgR, pS2, and genes encoding the growth factor amphiregulin.[59,71,84,85] Amphiregulin binds to EGFR and mediates signaling through intracellular pathways, including MAPK, Janus kinase (JAK), and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), to stimulate proliferation through Myc, Myb, ETS, and cyclin D1.[86]

Another example of paracrine/autocrine cross-talk was revealed upon examination of the proliferation rate in lobules of non-tumor-bearing women throughout the menstrual cycle. Breast tissue samples were collected from 83 women at different stages of the menstrual cycle and the samples were analyzed for proliferation and apoptotic rates. Interestingly, sequential cell multiplication (mitosis) and cell deletion (apoptosis) was observed during each menstrual cycle, with higher indices of both processes in the latter half of the cycle, with an apoptotic peak 3 days after the mitotic peak.[63] E2 and progesterone are targeted to the breast, so abundance of these hormones during the latter half of the menstrual cycle could cause an increase in proliferation, followed by apoptosis to maintain tissue homeostasis.

ERα INVOLVEMENT IN THE CELL CYCLE

Deregulated expression of key cell cycle regulators can trigger a cascade of events leading to mammary tumorigenesis. Both of the ER receptors have been shown to influence cellular proliferation and cell cycle events.[83]

Interactions with cell cycle machinery

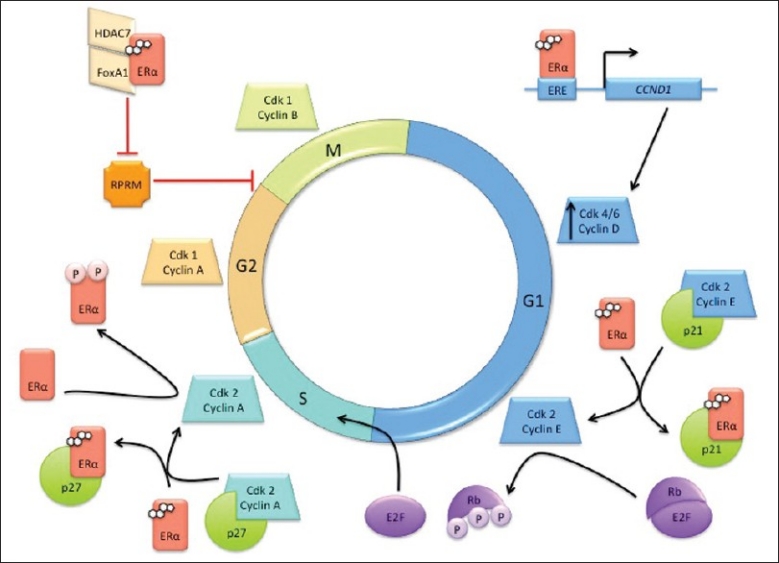

ERα can be linked to the cell cycle through its interaction with cyclin D1.[83] Cyclin D1 is a key regulator of the cell cycle and acts by binding to the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein and directing cyclin-dependent kinases, cdk4 and cdk6, to hyperphosphorylate Rb. This phosphorylation event results in the passage of cells from G1 to the S phase of the cell cycle[Figure 3].[87] Cyclin D1 is required for normal breast cell proliferation and for differentiation associated with pregnancy; however, cyclin D1 has also been found to be an important factor in breast cancer development.[88] To evaluate the oncogenic potential of cyclin D1, Weinstat et al. generated transgenic mice, which overexpressed cyclin D1. These mice exhibited malignant mammary cell proliferation followed by the development of mammary adenocarcinomas.[89] As additional evidence, cyclin D1 is amplified or overexpressed in a majority of human breast adenocarcinomas.[90,91]

Figure 3.

Involvement of ERα in the cell cycle. ERα plays many roles across the cell cycle phases, interacting with cell cycle machinery such as cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (cdk), cdk inhibitors, and the retinoblastoma protein (Rb)

Estrogen signaling can induce cyclin D1 expression via the binding of ligand-bound ER to an ERE site on the CCND1 promoter[Figure 3].[92] The effect of E2 addition to E2-deprived MCF-7 cells was observed using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, which revealed that ERα binds downstream of the cyclin D gene, which is important for its transactivation function.[93] Moreover, E2 increased the recruitment of p300 and Forkhead box protein 1 (FoxA1, an ERα transcriptional factor) to the cyclin D regulatory regions, preparing the site for transcriptional activation of cyclin D. Additionally, cyclin D mRNA and protein levels increase upon ERα, FoxA1, and p300 binding to the promoter, while cyclin D transcription is disrupted upon downregulation of each of these proteins.[94] The kinase activity of cdk4, the cyclin D binding partner, is also dependent on serum stimulation in the G1 phase.[95]

When serum-starved MCF-7 cells are stimulated by E2 to re-enter the cell cycle, cyclin E-cdk2 is activated and this complex can also hyperphosphorylate Rb, allowing the progression of cells from the G1 to S phase[Figure 3].[96] E2 (1 nM) was sufficient to induce cdk2-associated kinase (CAK) and Rb kinase activities to levels eightfold and fivefold higher, respectively, than that observed in growth-arrested cultures.[95] Levels of cyclins D and E in the growth-arrested MCF-7 cells were also increased post-E2 treatment.[96] It was also reported that E2-mediated transactivation of cyclin D results in overexpression of cyclin D, resulting in the shift of the p21 cdk inhibitor from the cyclin E-cdk2 complex to the cyclin D-cdk4 complex. The dissociation of p21 from cyclin E-cdk2[Figure 3] and association of p21 with cyclin D-cdk4 both result in activation of these cyclin-cdk complexes. These findings support the notion that E2 can manipulate cell cycle progression and, in the big picture, the proliferation rate of breast cancer cells by modulating the activities of G1 cyclin-cdk complexes.[96]

Cyclin A is another key cell cycle regulator linked to the ER pathway. Cyclin A shares several features with cyclin D, including the ability to phosphorylate Rb upon binding. Due to this function, it is reasonable to expect that changes in cyclin A expression levels would result in deregulation of the G1 to S cell cycle transition.[97,98] Phosphorylation of Ser104 and Ser106 of ERα via the cyclin A-cdk2 complex leads to an increase in ERα transcriptional activation [Figure 3]; however, this activity was observed to be independent of treatment with E2 or tamoxifen. These observations suggest a role of cyclin A-cdk2 in the activation of ERα for ligand-independent transcriptional activation through the ERα AF1 domain.[99]

ERα can also influence cell proliferation via direct protein-protein interactions with regulator proteins, including the p27 cdk inhibitor. p27 is the main inhibitor of the cyclin A-cdk2 complex and arrests cells in the S-phase, activating apoptosis.[52] ERα binds to the C-terminal region of p27 to sequester it in the cytoplasm and interrupts the p27 inhibitory activity in the cell cycle[Figure 3].[100]

E2 can also modulate cell cycle transitions through the inhibition of negative cell cycle regulators. For example, E2 can repress Reprimo (RPRM), a cell cycle inhibitor, which is induced following irradiation in a p53-dependent manner.[101,102] The overexpression of RPRM in various cell lines, including HeLa, MCF-7, and mouse NIH3T3 cells, resulted in a G2 arrest by inhibition of cdk1 activity and interference in the nuclear translocation of cyclin B1–cdk1 complex. In double thymidine-synchronized HeLa cells transduced with an RPRM adenovirus, a cytoplasmic accumulation of cyclin B1 was observed as well as inhibition of key mitotic events, such as chromosomal condensation.[103–105] The formation of a complex between ERα, histone deacetylase 7 (HDAC7), and FoxA1 is required to inhibit RPRM activity[Figure 3].[101] FoxA1 protein expression in breast cancer, as assessed by immunohistochemistry, has been associated with ERα-positivity and luminal A molecular subtyping. Additionally, the coexpression of FoxA1 and ERα was found to be a better predictor of survival than PgR expression.[106]

In MCF-7 cells treated with E2, cyclin G2 is another primary target gene that is robustly downregulated.[107,108] Contrary to the typical cyclin functions, cyclin G2 maintains cells in a quiescent state and prevents them from making the G1 to S phase transition.[109,110] The promoter of cyclin G2 contains a half-ERE site and a GC-rich region, which serve as the binding sites for ER and Sp-1, respectively. ChIP experiments showed that E2 supplementation led to recruitment of ER to the cyclin G2 promoter, dismissal of RNA polymerase II, and formation of a complex containing N-CoR (nuclear receptor corepressor) and deacetylases. Collectively, this complex leads to a hypoacetylated chromatin state capable of repressing expression of the cyclin G2 transcript.[108]

The role of ER in the G1 and S phases of the cell cycle has been described as a mediator of cell proliferation; however, the role of ER signaling in the G2 and M phases has not been explored as thoroughly. The key regulator of the G2 to M phase transition is the cyclin B-cdk1 complex, which resides as an active complex until the initiation of metaphase. In order for proliferating cells to enter anaphase, cyclin B needs to be degraded by the anaphase promoting complex (APC), the cyclin B ubiquitin ligase.[35] Mitotic arrest deficient 2 (MAD2) protein interacts with the APC and is present on chromosomes during cell division, where it is involved in the attachment of chromosomes to the mitotic spindle upon the onset of anaphase. MAD2 is also an APC inhibitor, resulting in the blockade of anaphase. ERα interacts directly with MAD2 and increases its activity; moreover, the ERβ/MAD2 complex helps to correct chromosome orientation in the mitotic spindle through binding of MAD2 to the kinetochores.[109] Based on this relationship between ERβ and MAD2 and the contrasting activities of the α and β isoforms of ER, one can posit that ERβ could have an inhibitory effect on the G2 and M phases of the cell cycle through regulation of chromosomal attachment to the mitotic spindles prior to anaphase entry.

There has also been evidence presented for cross-talk between ERα and cyclin B. A study by Gustafsson et al. examined how RanBP-type and C3HC4-type zinc finger-containing protein 1 (RBCK1), a protein kinase C1 (PKC1) interacting protein, result in the progression of cell cycle by driving transcription of ERα and cyclin B in ER-positive breast cancer cells.[110] ChIP analysis on parental MCF-7 cells revealed that RBCK1 is recruited to the major ERα promoter region, resulting in the induction of ERα mRNA levels. Interestingly, no RBCK1 was detected on the cyclin B promoter, but RBCK1 silencing resulted in G2 arrest and reduced levels of both ERα and cyclin B mRNA and protein. The reintroduction of cyclin B, but not ERα, released the cells from the observed G2 arrest.[110,111] While this study highlighted the implicit role of cyclin B in the cell cycle, it also suggested the novel importance of ERα.

Interactions with cell cycle effector molecules

E2 and ER signaling can also affect cell cycle progression by interacting with proteins other than the traditional cyclin and cdk machinery, including Rb, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), insulin receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu).[112–123]

The retinoblastoma protein (Rb) is a tumor suppressor, such that it has an inhibitory effect on cell cycle progression. In terms of the cycle, Rb is involved with the G1 checkpoint and effectively blocks S phase entry by binding the transactivation domain of the E2F transcription factor.[112] The Rb protein is hyperphosphorylated by cyclins A, D, and E, which frees E2F to perform its transcription factor functions and facilitate the G1 to S phase transition.[89,97,98] Treatment of MCF-7 cells with E2 has also been shown to downregulate Rb at the levels of mRNA and protein by 50% and 70%, respectively.[113] Ligand-bound ERα binds to the Sp1 site of the retinoblastoma binding protein 1 gene (RBBP1) and activates transcription of the RBP1 protein. Once translated, RBP1 binds in the Rb binding pocket and further promotes cell cycle inhibition via recruitment of HDAC-dependent and HDAC-independent repression activities.[114,115] Additional studies have shown an increased risk of breast cancer in the mothers of children who suffer from retinoblastoma or osteosarcoma.[116]

Transcription of the gene encoding the TNF-α proteins is also repressed by E2 signaling.[117] TNF-α plays a role in translocation of the p21 and p27 cdk inhibitors to the nucleus, where they can facilitate their inhibitory effect on the cell cycle. This role was studied in TNF-α-resistant MCF-7 cells, where p21 and p27 were mislocalized to the cytoplasm.[118] E2-bound ERβ is a potent repressor of the transcription of the gene encoding TNF-α, but ERα is also able to perform this transcriptional repression.[117] Together, these observations suggest that ER could prevent the nuclear translocation of p21 and p27 through repression of TNF-α, leading to an uncontrolled cell cycle.

The insulin receptor interacts with a docking protein, insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1), which can translocate to the nucleus and activate the c-myc and cyclin D1 gene promoters.[119] Therefore, propagation of the insulin receptor/IRS-1 signaling leads to cell cycle activating events. On the contrary, estrogen signaling downregulates expression of the insulin receptor at the transcriptional level.[120] These findings suggest that downregulation of insulin receptor expression can lead to decreased activation of the IRS-1 protein, thus abrogating the effect of cell cycle progression through estrogen signaling.

HER2/neu or ErbB2 promotes cell cycle progression through the G1 to S phase transition in SKBr3 cells, ErbB2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. This activity was modulated via redistribution of the p27 cdk inhibitor from cyclin E-cdk 2 complexes to sequestering complexes, thus enhancing cyclin E-cdk2 kinase activity.[121] The first intron of ERBB2 has an estrogen-suppressible enhancer, such that E2 can suppress the transcription of the ERBB2 gene. This causes a decrease in the levels of ErbB2 mRNA and protein in ER-positive breast cancer cells.[122,123] Together, these examples highlight various roles of estrogen signaling in the downregulation of ER target genes, leading to cell cycle stimulation and cell proliferation.

Effects of tamoxifen-bound ERα on the cell cycle

Association of ERα with tamoxifen, an ERα antagonist, results in the transcriptional repression of ERα target genes. At the promoters of these genes, a corepressor complex is formed, which contains N-CoR and the silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid (SMRT) hormone receptor. However, the silencing of N-CoR and SMRT led to tamoxifen-induced cell cycle stimulation. Upon the silencing of N-CoR and SMRT in MCF-7 cells, treatment with E2 or tamoxifen did not alter the activation of such ERα target genes as c-myc, cyclin D1, or stromal-derived factor 1; however, XBP-1 was markedly elevated.[124] Additionally, in MCF-7-derived tamoxifen-resistant cells, XBP-1 expression was elevated threefold over the parental cell line.[125] The role of XBP-1 in estrogen- or tamoxifen-mediated cell proliferation has yet to be discovered. Together, these findings suggest that N-CoR and SMRT prevent tamoxifen from stimulating breast cancer cell proliferation through the repression of XBP-1.

CONCLUSIONS

This review has demonstrated a potential correlation between ERα and cell cycle events such that ERα hastens the passage of cells through the S to G2 phase transition by upregulating ERα target genes and, ultimately, increased cellular proliferation. Estrogen signaling through the estrogen receptor has been shown to affect the activities of traditional cell cycle machinery, as well as that of cell cycle effector molecules. Further studies into the correlation of ERα with the cell cycle may prove to be of great significance.

AUTHOR'S PROFILE

Dr. Sonia Javan Moghadam, Department of Experimental Radiation Oncology at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030

Amanda Marie Hanks, Department of Experimental Radiation Oncology at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030

Dr. Khandan Keyomarsi, Department of Experimental Radiation Oncology at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030

REFERENCES

- 1.MacGregor JI, Jordan VC. Basic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen action. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:151–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson S, Mäkelä S, Treuter E, Tujague M, Thomsen J, Andersson G, et al. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1535–65. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah YM, Rowan BG. The Src kinase pathway promotes tamoxifen agonist action in Ishikawa endometrial cells through phosphorylation-dependent stabilization of estrogen receptor (alpha) promoter interaction and elevated steroid receptor coactivator 1 activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:732–48. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutertre M, Smith CL. Ligand-independent interactions of p160/steroid receptor coactivators and CREB-binding protein (CBP) with estrogen receptor-alpha: regulation by phosphorylation sites in the A/B region depends on other receptor domains. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1296–314. doi: 10.1210/me.2001-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams CC, Basu A, El-Gharbawy A, Carrier LM, Smith CL, Rowan BG. Identification of four novel phosphorylation sites in estrogen receptor alpha: impact on receptor-dependent gene expression and phosphorylation by protein kinase CK2. BMC Biochem. 2009;10:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skafar DF, Zhao C. The multifunctional estrogen receptor-alpha F domain. Endocrine. 2008;33:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12020-008-9054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green S, Kumar V, Krust A, Walter P, Chambon P. Structural and functional domains of the estrogen receptor. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1986;51:751–8. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1986.051.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ascenzi P, Bocedi A, Marino M. Structure-function relationship of estrogen receptor α and β: Impact on human health. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27:299–402. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunone G, Briand PA, Miksicek RJ, Picard D. Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by EGF involves the MAP kinase pathway and direct phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2174–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joel PB, Smith J, Sturgill TW, Fisher TL, Blenis J, Lannigan DA. pp90rsk1 regulates estrogen receptor-mediated transcription through phosphorylation of Ser-167. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1978–84. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lannigan DA. Estrogen receptor phosphorylation. Steroids. 2003;68:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogatsky I, Trowbridge JM, Garabedian MJ. Potentiation of human estrogen receptor alpha transcriptional activation through phosphorylation of serines 104 and 106 by the cyclin A-CDK2 complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22296–302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joel PB, Traish AM, Lannigan DA. Estradiol and phorbol ester cause phosphorylation of serine 118 in the human estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:1041–52. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.8.7476978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gougelet A, Bouclier C, Marsaud V, Maillard S, Mueller SO, Korach KS, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta subtype expression and transactivation capacity are differentially affected by receptor-, hsp90-, and immunophilin-ligands in human breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;94:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picard D. Heat-shock protein 90, a chaperone for folding and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1640–8. doi: 10.1007/PL00012491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer MP. Gymnastics of molecular chaperones. Mol Cell. 2010;39:321–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barone I, Brusco L, Fuqua SA. Estrogen receptor mutations and changes in downstream gene expression and signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2702–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kee BL, Arias J, Montminy MR. Adaptor-mediated recruitment of RNA polymerase II to a signal-dependent activator. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2373–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landers JP, Spelsberg TC. New concepts in steroid hormone action: transcription factors, proto-oncogenes, and the cascade model for steroid regulation of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1992;2:19–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaub MP, Bellard M, Scheuer I, Chambon P, Sassone-Corsi P. Activation of the ovalbumin gene by the estrogen receptor involves the fos-jun complex. Cell. 1990;63:1267–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90422-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tora L, Gaub MP, Mader S, Dierich A, Bellard M, Chambon P. Cell-specific activity of a GGTCA half-palindromic oestrogen-responsive element in the chicken ovalbumin gene promoter. EMBO J. 1988;7:3771–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philips A, Chalbos D, Rochefort H. Estradiol increases and anti-estrogens antagonize the growth factor-induced activator protein-1 activity in MCF7 breast cancer cells without affecting c-fos and c-jun synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14103–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umayahara Y, Kawamori R, Watada H, Imano E, Iwama N, Morishima T, et al. Estrogen regulation of the insulin-like growth factor I gene transcription involves an AP-1 enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16433–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzukerman M, Zhang XK, Pfahl M. Inhibition of estrogen receptor activity by the tumor promoter 12-O-tetradeconylphorbol-13-acetate: a molecular analysis. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1983–92. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-12-1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saatcioglu F, Lopez G, West BL, Zandi E, Feng W, Lu H, et al. Mutations in the conserved C-terminal sequence in thyroid hormone receptor dissociate hormone-dependent activation from interference with AP-1 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4687–95. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webb P, Lopez GN, Uht RM, Kushner PJ. Tamoxifen activation of the estrogen receptor/AP-1 pathway: potential origin for the cell-specific estrogen-like effects of antiestrogens. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:443–56. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.4.7659088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kushner PJ, Agard D, Feng WJ, Lopez G, Schiau A, Uht R, et al. Oestrogen receptor function at classical and alternative response elements. Novartis Found Symp. 2000;230:20–6. doi: 10.1002/0470870818.ch3. discussion 27-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gururaj AE, Rayala SK, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. Novel mechanisms of resistance to endocrine therapy: genomic and nongenomic considerations. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1001s–7s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1951–9. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjornstrom L, Sjoberg M. Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:833–42. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doolan CM, Harvey BJ. A Galphas protein-coupled membrane receptor, distinct from the classical oestrogen receptor, transduces rapid effects of oestradiol on [Ca2+]i in female rat distal colon. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;199:87–103. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simoncini T, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Brazil DP, Ley K, Chin WW, Liao JK. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature. 2000;407:538–41. doi: 10.1038/35035131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu W, Liu LZ, Loizidou M, Ahmed M, Charles IG. The role of nitric oxide in cancer. Cell Res. 2002;12:311–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriarty K, Kim KH, Bender JR. Minireview: estrogen receptor-mediated rapid signaling. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5557–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, Koh SS, Huang SM, Schurter BT, et al. Regulation of transcription by a protein methyltransferase. Science. 1999;284:2174–7. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Losel RM, Falkenstein E, Feuring M, Schultz A, Tillmann HC, Rossol-Haseroth K, et al. Nongenomic steroid action: controversies, questions, and answers. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:965–1016. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cato AC, Nestl A, Mink S. Rapid actions of steroid receptors in cellular signaling pathways. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:re9. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.138.re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiang CH, Cheng KW, Igarashi S, Nathwani PS, Leung PC. Hormonal regulation of estrogen receptor alpha and beta gene expression in human granulosa-luteal cells in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3828–39. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Improta-Brears T, Whorton AR, Codazzi F, York JD, Meyer T, McDonnell DP. Estrogen-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase requires mobilization of intracellular calcium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4686–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li L, Haynes MP, Bender JR. Plasma membrane localization and function of the estrogen receptor alpha variant (ER46) in human endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831079100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Figtree GA, McDonald D, Watkins H, Channon KM. Truncated estrogen receptor alpha 46-kDa isoform in human endothelial cells: relationship to acute activation of nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2003;107:120–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043805.11780.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norfleet AM, Thomas ML, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Estrogen receptor-alpha detected on the plasma membrane of aldehyde-fixed GH3/B6/F10 rat pituitary tumor cells by enzyme-linked immunocytochemistry. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3805–14. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Z, Yuhanna IS, Galcheva-Gargova Z, Karas RH, Mendelsohn ME, Shaul PW. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates the nongenomic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by estrogen. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:401–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson CS, Norfleet AM, Pappas TC, Gametchu B. Rapid actions of estrogens in GH3/B6 pituitary tumor cells via a plasma membrane version of estrogen receptor-alpha. Steroids. 1999;64:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev. 1999;20:358–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levin ER. Bidirectional signaling between the estrogen receptor and the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:309–17. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alroy I, Yarden Y. The ErbB signaling network in embryogenesis and oncogenesis: signal diversification through combinatorial ligand-receptor interactions. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:83–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kahlert S, Nuedling S, van Eickels M, Vetter H, Meyer R, Grohe C. Estrogen receptor alpha rapidly activates the IGF-1 receptor pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18447–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910345199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Filardo EJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transactivation by estrogen via the G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: a novel signaling pathway with potential significance for breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;80:231–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simoncini T. Mechanisms of action of estrogen receptors in vascular cells: relevance for menopause and aging. Climacteric. 2009;12 Suppl 1:6–11. doi: 10.1080/13697130902986385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson RG. The caveolae membrane system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:199–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Azarnia R, Reddy S, Kmiecik TE, Shalloway D, Loewenstein WR. The cellular src gene product regulates junctional cell-to-cell communication. Science. 1988;239:398–401. doi: 10.1126/science.2447651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kavanaugh WM, Williams LT. An alternative to SH2 domains for binding tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. Science. 1994;266:1862–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7527937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Razandi M, Pedram A, Park ST, Levin ER. Proximal events in signaling by plasma membrane estrogen receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2701–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Di Domenico M, de Falco A, Bilancio A, Lombardi M, et al. Sex steroid hormones act as growth factors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;83:31–5. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong CW, McNally C, Nickbarg E, Komm BS, Cheskis BJ. Estrogen receptor-interacting protein that modulates its nongenomic activity-crosstalk with Src/Erk phosphorylation cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14783–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192569699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Song RX, McPherson RA, Adam L, Bao Y, Shupnik M, Kumar R, et al. Linkage of rapid estrogen action to MAPK activation by ERalpha-Shc association and Shc pathway activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:116–27. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun M, Paciga JE, Feldman RI, Yuan Z, Coppola D, Lu YY, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH Kinase (PI3K)/AKT2, activated in breast cancer, regulates and is induced by estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha) via interaction between ERalpha and PI3K. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5985–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Russo J, Ao X, Grill C, Russo IH. Pattern of distribution of cells positive for estrogen receptor alpha and progesterone receptor in relation to proliferating cells in the mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;53:217–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1006186719322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anderson TJ, Ferguson DJ, Raab GM. Cell turnover in the “resting” human breast: influence of parity, contraceptive pill, age and laterality. Br J Cancer. 1982;46:376–82. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Battersby S, Robertson BJ, Anderson TJ, King RJ, McPherson K. Influence of menstrual cycle, parity and oral contraceptive use on steroid hormone receptors in normal breast. Br J Cancer. 1992;65:601–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferguson DJ, Anderson TJ. Morphological evaluation of cell turnover in relation to the menstrual cycle in the “resting” human breast. Br J Cancer. 1981;44:177–81. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Going JJ, Anderson TJ, Battersby S, MacIntyre CC. Proliferative and secretory activity in human breast during natural and artificial menstrual cycles. Am J Pathol. 1988;130:193–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meyer JS. Cell proliferation in normal human breast ducts, fibroadenomas, and other ductal hyperplasias measured by nuclear labeling with tritiated thymidine.Effects of menstrual phase, age, and oral contraceptive hormones. Hum Pathol. 1977;8:67–81. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(77)80066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Masters JR, Drife JO, Scarisbrick JJ. Cyclic Variation of DNA synthesis in human breast epithelium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;58:1263–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/58.5.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Potten CS, Watson RJ, Williams GT, Tickle S, Roberts SA, Harris M, et al. The effect of age and menstrual cycle upon proliferative activity of the normal human breast. Br J Cancer. 1988;58:163–70. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams G, Anderson E, Howell A, Watson R, Coyne J, Roberts SA, et al. Oral contraceptive (OCP) use increases proliferation and decreases oestrogen receptor content of epithelial cells in the normal human breast. Int J Cancer. 1991;48:206–10. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laidlaw IJ, Clarke RB, Howell A, Owen AW, Potten CS, Anderson E. The proliferation of normal human breast tissue implanted into athymic nude mice is stimulated by estrogen but not progesterone. Endocrinology. 1995;136:164–71. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.1.7828527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Podhajcer OL, Bravo AI, Sorin I, Guman N, Cerdeiro R, Mordoh J. Determination of DNA synthesis, estrogen receptors, and carcinoembryonic antigen in isolated cellular subpopulations of human breast cancer. Cancer. 1986;58:720–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860801)58:3<720::aid-cncr2820580320>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Russo IH, Russo J. Role of hormones in mammary cancer initiation and progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1998;3:49–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1018770218022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Clarke RB, Howell A, Potten CS, Anderson E. Dissociation between steroid receptor expression and cell proliferation in the human breast. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4987–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Russo IH, RussoJ Role of hormones in cancer initiation and progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1998;3:49–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1018770218022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Russo J, Reina D, Frederick J, Russo IH. Expression of phenotypical changes by human breast epithelial cells treated with carcinogens in vitro. Cancer Res. 1988;48:2837–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Russo J, Calaf G, Russo IH. A critical approach to the malignant transformation of human breast epithelial cells with chemical carcinogens. Crit Rev Oncog. 1993;4:403–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Russo J, Gusterson BA, Rogers AE, Russo IH, Wellings SR, van Zwieten MJ. Comparative study of human and rat mammary tumorigenesis. Lab Invest. 1990;62:244–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gerdes J, Schwab U, Lemke H, Stein H. Production of a mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with a human nuclear antigen associated with cell proliferation. Int J Cancer. 1983;31:13–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kodama F, Greene GL, Salmon SE. Relation of estrogen receptor expression to clonal growth and antiestrogen effects on human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2720–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Clarke R, Dickson RB, Lippman ME. Hormonal aspects of breast cancer.Growth factors, drugs and stromal interactions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1992;12:1–23. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(92)90062-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knabbe C, Lippman ME, Wakefield LM, Flanders KC, Kasid A, Derynck R, et al. Evidence that transforming growth factor-beta is a hormonally regulated negative growth factor in human breast cancer cells. Cell. 1987;48:417–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dickson RB, Lippman ME. Control of human breast cancer by estrogen, growth factors, and oncogenes. Cancer Treat Res. 1988;40:119–65. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1733-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saji S, Jensen EV, Nilsson S, Rylander T, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the rodent mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:337–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carroll JS, Lynch DK, Swarbrick A, Renoir JM, Sarcevic B, Daly RJ, et al. p27(Kip1) induces quiescence and growth factor insensitivity in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4322–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dos Santos E, Dieudonné MN, Leneveu MC, Sérazin V, Rincheval V, Mignotte B, et al. Effects of 17beta-estradiol on preadipocyte proliferation in human adipose tissue: Involvement of IGF1-R signaling. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42:514–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seagroves TN, Lydon JP, Hovey RC, Vonderhaar BK, Rosen JM. C/EBPbeta (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein) controls cell fate determination during mammary gland development. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:359–68. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.3.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zeps N, Bentel JM, Papadimitriou JM, D′Antuono MF, Dawkins HJ. Estrogen receptor-negative epithelial cells in mouse mammary gland development and growth. Differentiation. 1998;62:221–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1998.6250221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Clarke RB. Human breast cell proliferation and its relationship to steroid receptor expression. Climacteric. 2004;7:129–37. doi: 10.1080/13697130410001713751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–7. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weinstat-Saslow D, Merino MJ, Manrow RE, Lawrence JA, Bluth RF, Wittenbel KD, et al. Overexpression of cyclin D mRNA distinguishes invasive and in situ breast carcinomas from non-malignant lesions. Nat Med. 1995;1:1257–60. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang TC, Cardiff RD, Zukerberg L, Lees E, Arnold A, Schmidt EV. Mammary hyperplasia and carcinoma in MMTV-cyclin D1 transgenic mice. Nature. 1994;369:669–71. doi: 10.1038/369669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Courjal F, Louason G, Speiser P, Katsaros D, Zeillinger R, Theillet C. Cyclin gene amplification and overexpression in breast and ovarian cancers: evidence for the selection of cyclin D1 in breast and cyclin E in ovarian tumors. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:247–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960822)69:4<247::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gillett C, Fantl V, Smith R, Fisher C, Bartek J, Dickson C, et al. Amplification and overexpression of cyclin D1 in breast cancer detected by immunohistochemical staining. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1812–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cicatiello L, Addeo R, Sasso A, Altucci L, Petrizzi VB, Borgo R, et al. Estrogens and progesterone promote persistent CCND1 gene activation during G1 by inducing transcriptional derepression via c-Jun/c-Fos/estrogen receptor (progesterone receptor) complex assembly to a distal regulatory element and recruitment of cyclin D1 to its own gene promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7260–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7260-7274.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell. 2000;103:843–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eeckhoute J, Carroll JS, Geistlinger TR, Torres-Arzayus MI, Brown M. A cell-type-specific transcriptional network required for estrogen regulation of cyclin D1 and cell cycle progression in breast cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2513–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.1446006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Matsushime H, Quelle DE, Shurtleff SA, Shibuya M, Sherr CJ, Kato JY. D-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2066–76. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Foster JS, Wimalasena J. Estrogen regulates activity of cyclin-dependent kinases and retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:488–98. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.5.8732680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Resnitzky D, Reed SI. Different roles for cyclins D1 and E in regulation of the G1-to-S transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3463–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bremner R, Cohen BL, Sopta M, Hamel PA, Ingles CJ, Gallie BL, et al. Direct transcriptional repression by pRB and its reversal by specific cyclins. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3256–65. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rogatsky I, Trowbridge JM, Garabedian MJ. Potentiation of human estrogen receptor alpha transcriptional activation through phosphorylation of serines 104 and 106 by the cyclin A-CDK2 complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22296–302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Beato M, Klug J. Steroid hormone receptors: an update. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6:225–36. doi: 10.1093/humupd/6.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Malik S, Jiang S, Garee JP, Verdin E, Lee AV, O′Malley BW, et al. Histone deacetylase 7 and FoxA1 in estrogen-mediated repression of RPRM. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:399–412. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00907-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ohki R, Nemoto J, Murasawa H, Oda E, Inazawa J, Tanaka N, et al. Reprimo, a new candidate mediator of the p53-mediated cell cycle arrest at the G2 phase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22627–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jin S, Tong T, Fan W, Fan F, Antinore MJ, Zhu X, et al. GADD45-induced cell cycle G2-M arrest associates with altered subcellular distribution of cyclin B1 and is independent of p38 kinase activity. Oncogene. 2002;21:8696–704. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Taylor WR, DePrimo SE, Agarwal A, Agarwal ML, Schönthal AH, Katula KS, et al. Mechanisms of G2 arrest in response to overexpression of p53. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3607–22. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Winters ZE, Ongkeko WM, Harris AL, Norbury CJ. p53 regulates Cdc2 independently of inhibitory phosphorylation to reinforce radiation-induced G2 arrest in human cells. Oncogene. 1998;17:673–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Badve S, Turbin D, Thorat MA, Morimiya A, Nielsen TO, Perou CM, et al. FOXA1 expression in breast cancer--correlation with luminal subtype A and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4415–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Frasor J, Danes JM, Komm B, Chang KC, Lyttle CR, Katzenellenbogen BS. Profiling of estrogen up- and down-regulated gene expression in human breast cancer cells: insights into gene networks and pathways underlying estrogenic control of proliferation and cell phenotype. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4562–74. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stossi F, Likhite VS, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen-occupied estrogen receptor represses cyclin G2 gene expression and recruits a repressor complex at the cyclin G2 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16272–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Poelzl G, Kasai Y, Mochizuki N, Shaul PW, Brown M, Mendelsohn ME. Specific association of estrogen receptor beta with the cell cycle spindle assembly checkpoint protein, MAD2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2836–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050580997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gustafsson N, Zhao C, Gustafsson JA, Dahlman-Wright K. RBCK1 drives breast cancer cell proliferation by promoting transcription of estrogen receptor alpha and cyclin B1. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1265–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Horne MC, Donaldson KL, Goolsby GL, Tran D, Mulheisen M, Hell JW, et al. Cyclin G2 is up-regulated during growth inhibition and B cell antigen receptor-mediated cell cycle arrest. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12650–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Giacinti C, Giordano A. RB and cell cycle progression. Oncogene. 2006;25:5220–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gottardis MM, Saceda M, Garcia-Morales P, Fung YK, Solomon H, Sholler PF, et al. Regulation of retinoblastoma gene expression in hormone-dependent breast cancer. Endocrinology. 1995;136:5659–65. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.12.7588321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Monroe DG, Secreto FJ, Hawse JR, Subramaniam M, Khosla S, Spelsberg TC. Estrogen receptor isoform-specific regulation of the retinoblastoma binding protein 1 (RBBP1) gene: roles of AF1 and enhancer elements. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28596–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lai A, Lee JM, Yang WM, DeCaprio JA, Kaelin WG, Jr, Seto E, et al. RBP1 recruits both histone deacetylase-dependent and -independent repression activities to retinoblastoma family proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6632–41. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.T'Ang A, Varley JM, Chakraborty S, Murphree AL, Fung YK. Structural rearrangement of the retinoblastoma gene in human breast carcinoma. Science. 1988;242:263–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3175651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.An J, Ribeiro RC, Webb P, Gustafsson JA, Kushner PJ, Baxter JD, et al. Estradiol repression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha transcription requires estrogen receptor activation function-2 and is enhanced by coactivators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15161–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang Z, Kishimoto H, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Crean C, Nakshatri H. TNFalpha resistance in MCF-7 breast cancer cells is associated with altered subcellular localization of p21CIP1 and p27KIP1. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:98–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wu A, Chen J, Baserga R. Nuclear insulin receptor substrate-1 activates promoters of cell cycle progression genes. Oncogene. 2008;27:397–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Garcia-Arencibia M, Molero S, Davila N, Carranza MC, Calle C. 17beta-Estradiol transcriptionally represses human insulin receptor gene expression causing cellular insulin resistance. Leuk Res. 2005;29:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Neve RM, Sutterlüty H, Pullen N, Lane HA, Daly JM, Krek W, et al. Effects of oncogenic ErbB2 on G1 cell cycle regulators in breast tumour cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:1647–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Perissi V, Menini N, Cottone E, Capello D, Sacco M, Montaldo F, et al. AP-2 transcription factors in the regulation of ERBB2 gene transcription by oestrogen. Oncogene. 2000;19:280–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Newman SP, Bates NP, Vernimmen D, Parker MG, Hurst HC. Cofactor competition between the ligand-bound oestrogen receptor and an intron 1 enhancer leads to oestrogen repression of ERBB2 expression in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:490–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Keeton EK, Brown M. Cell cycle progression stimulated by tamoxifen-bound estrogen receptor-alpha and promoter-specific effects in breast cancer cells deficient in N-CoR and SMRT. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1543–54. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Semlali A, Oliva J, Badia E, Pons M, Duchesne MJ. Immediate early gene X-1 (IEX-1), a hydroxytamoxifen regulated gene with increased stimulation in MCF-7 derived resistant breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;88:247–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]