Abstract

We have developed a novel approach, the Digital Crumb Investigator, for using data collected as a byproduct of Electonic Health Record (EHR) use to help define care teams and care processes. We are developing tools and methods to utilize these routinely collected data to visualize and quantify care networks across acute care and ambulatory settings We have chosen a clinical care domain where clinicians use EHRs in their offices, on the maternity wards and in the neonatal intensive care units as a test paradigm for this technology. The tools and methods we deliver should readily translate to other health care settings that collect behind-the-scenes electronic metadata such as audit trails. We believe that by applying the methods of social networking to define clinical relationships around a patient’s care we will enable new areas of research into the usage of EHRs to promote patient safety and other improvements in care.

Introduction

An EHR contains highly granular data regarding a patient’s care, status and outcomes. In addition, these records contain data about who has entered information into the record and who has viewed it. These metadata can be used to infer who makes up the team of providers caring for an individual over time and to identify the relationships among patients’ care teams. However, the patient-centric views of these data that are most used by clinicians and administrators as well as the methods used for data transfer to health information exchanges often ignore or discard information that allows characterization of care team structure. The lack of attention paid to this class of information is especially relevant given recent work in multiple domains that demonstrates the importance of an individual’s social ties on health status. The tools we develop will be used to apply and create network analytic metrics to understand the relationship between care team assembly and resulting structure and health outcomes.

This work is being done in a large tertiary care obstetric/newborn care service served by a robust EHR spanning outpatient and inpatient care. The patient population includes both high and low risk obstetrics as well as the full range of newborn care up to and including intensive care. The relatively homogenous nature of this population results in a limited number of co-morbidities that could potentially confound the relationship between care team structure and health outcomes. This will allow us to define a series of important relevant health outcomes and to rigorously evaluate the relation between care team structure and these outcomes.

The knowledge gained and the tools created in this body of work are expected to have myriad applications that will extend beyond the current study population. At a basic level they will promote a greater understanding of how EHR-based data can be used to examine the complex social networks in which patients exist. At a practical level they will provide clinical leaders with real-time methods for monitoring and improving the quality of care teams that assemble around patients, particularly at critical junctures such as during the root cause analysis of outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant nosocomial infections.

Background

Network science and complex systems

The past decade has seen an explosion in the use of network analytic approaches to examine a diverse array of complex systems ranging from the internet and electric power grids to intracellular metabolic networks, as well as teams involved in scientific collaborations[1–2]. This increase has been fueled in part by development of new analytic approaches and tools as well as the recent availability of highly granular datasets that describe these systems [3]. These investigations have led to an improved understanding of the function of these complex systems. Across the diverse spectrum of system types studied, it has become clear that the performance and fault tolerance of these networks or teams is related to both network topology and the ways in which they form over time [4–5].

Network representation

Network analysis conceptualizes a system as being made up of the intersection of two sets [6]. The first, called the node or vertex list, represents the objects of interest in a system. Examples include a collection of routers or World Wide Web (WWW) pages on the Internet, written words or individual patients. The nodes in a network may be made up of one object type (uni-partite networks) or more than one type (e.g., bi-partite networks). The connections or ties that exist between these objects are contained in the second set, termed the edge or arc list. Edges represent non-directed links while arcs represent directed connections. For example, a WWW page may be connected to another by a hyperlink it contains, and individuals may be linked through family ties, the occurrence of person-to-person contact/communication or membership in a common group. The last of these, in which members of the first node type (i.e., individuals) are indirectly linked through an intermediary node of a second type (i.e., group), is an example of a special type of bi-partite network called an affiliation network.

In addition, within a network, individual nodes can be characterized by one or more numerical or categorical attributes. These attributes can be used to select nodes that comprise sub-networks of interest. Both edges and arcs can be assigned numerical weights. These weights may represent characteristics such as distance between two nodes (e.g., miles between cities on a highway) or cost to traverse the edge/arc.

Network visualization

A number of tools exist that can be used to create graphical representations of networks [7–8]. These visualizations are an important first step in understanding network topology [9]. They can allow identification of nodes of interest and assist in the characterization of the network’s macro-structure. Figure 1 below illustrates the use of Pajek [8], a public domain application capable of displaying and analyzing networks with as many as 10,000,000 nodes. Here, a small bi-partite network is displayed from NICU data collected over a two-week period. Squares represent the 24 physical two-patient rooms present within the NICU. Rooms are labeled with an attribute equal to their room number. Circles represent the patients cared for during that 2-week period. During this interval, an unusual clustering of grossly bloody stools occurred in 7 patients (dark red circles). The edges represent the links between patients and the rooms they occupied. The placement of rooms in this graphic do not mirror their physical locations, but instead is based on algorithms that cluster nodes together based on their connectedness. Interestingly, 4/7 cases were clustered in 3 rooms that experienced significant crossover of patients.

Figure 1:

Visual representation of an affiliation network derived from NICU data. Squares represent patient rooms and circles represent patients cared for in those rooms. Darker red circles represent patients with episodes of bloody stools during this period.

The network depiction in Figure 1 is static, containing a summary of all connections existing over the entire period. However, this network is in reality a dynamic structure and changes over time. Nodes might come and go (i.e., infants are admitted to and discharged from the NICU), connections might form and break (i.e., infants are moved between bed spaces) or the attributes of nodes (infants) might change (i.e., they may develop bloody stools or have these symptoms resolve). This evolution of the network can be displayed through animations that create snapshots of the network as it existed at successive points in time. This type of dynamic representation allows us to see how different changes in the network propagate through it and affect other nodes over time.

Network analytics

In quantitative analysis of a network, either ego-centric or socio-centric perspectives can be used. In ego-centric models, the focus is placed on an individual node and its relationship to its neighbors as well as its position within the network as a whole. In socio-centric models the emphasis is placed on the characteristics of the network as a singular encompassing object. The choice of perspective depends on the question at hand [10]. For example, an egocentric approach might be used to understand how an individual patient within a hospital unit was exposed to an infectious agent based on his/her connections to others in the unit. However, to understand how the structure of connections within the unit affects the propensity for spread of an organism, a socio-centric approach would be needed. A wide variety of analytic measures and methods are available to examine network characteristics both at single points in time and as the network evolves [11–12].

Social networks and health

There has also recently been increasing recognition that the structure and formation of an individual’s personal ties or social network influence various aspects of health. While the importance of one’s connectedness is an obvious aspect of infectious disease spread [13–14], these social networks have also been implicated in the occurrence of other morbidities [15], as well as the spread of healthy [16–18] and unhealthy behaviors [19–21]. Knowledge of these influences is important not only in understanding disease epidemiology but also in attempting to structure interventions [22].

Relevance of social networks to health care practice

A large body of evidence exists that demonstrates the importance of organizational characteristics of care as predictors of performance across multiple domains of care [23–27]. These characteristics are predictors not only of clinical outcomes, but also of patient and provider satisfaction. Although the term “team” is often applied to the groups of providers who come together to care for a patient, it is not always clear that these groups truly are teams. Grumbach and Sodenheimer suggest that two elements are crucial if these groups are to function successfully [28]. These include appropriate composition and successful communication. In other research on collaborative ventures, investigators have stressed the impact of team size and the incorporation of newcomers into a team on team function and success [4, 29].

Most research on these topics has required data collection strategies that rely upon dedicated research associates to administer surveys, observe practice and interactions and assess outcomes. As such, these approaches are unsustainable in settings outside of a research paradigm. Approaches that allow automatic collection and analysis of data that identifies individuals involved in a patient’s care could allow these techniques to be integrated into quality improvement efforts and may expand opportunities for further research.

Role for electronic health records in assessing team structure and function

Clinical information systems such as those developed and deployed at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center [30–31] are a complex integration of departmental systems and tools to retrieve and display patient-specific information. Systems that allow clinicians to document clinical narrative and support patient management are now called Electronic Health Records [32]. Each of these systems keeps detailed audit trails to insure the integrity of the information and to assist in maintaining patient confidentiality [33]. These metadata provides a highly granular dataset describing which providers may have interacted with that patient and therefore comprise the patient’s care team. EHRs are therefore analogous to the rich datasets that in other domains, through the application of network analytics, have allowed major breakthroughs in understanding complex systems such as electric power grids, intracellular metabolic networks and the entity now referred to as the “Diseasesome” [2, 34].

Methods

Identification of relevant data sources

Working with clinical and informatics leaders as well as bedside clinicians, we have catalogued data sources within the EHR that can identify clinical care connections between patient providers and physical locations across time. We have developed a system for characterizing these node to node connections into one of 16 types as well as partitioning their occurrence into useful time slices. For example, entry of an online medical record (OMR) or ICU progress note into a patient’s record by a given clinician would denote a given type of connection while lookups in the laboratory information of that patient’s laboratory results would specify a different connection type. Timestamps for each use of the patient’s EHR would allow dynamic assessments of these connections between patients and clinicians. Addition of admission, discharge and transfer (ADT) information would allow an additional dimension, that of patient connection to physical locations to these networks.

Development of Platform Architecture

We have designed a unified software architecture for retrieving and integrating network defining information from the above data stores as well as visualizing and quantifying user selected patient care network networks. Depicted in Figure 2, this architecture also provides for de-identification of protected health information, allowing for ease of the use of these networks in research endeavors. Various projections of the retrieved and aggregated information can be created depending on the question under study.

Figure 2:

Digital Crumb Investigator Architecture

The socio-centric network in Figure 2, derived from ICU progress note metadata demonstrated a group of providers involved in the care of an individual patient over the course of a hospitalization. The edges located between patients represent the clinician to clinician handoffs that occurred.

Setting

Electronic Health Records at BIDMC

The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center has a clinical information system that has been in constant evolution for more than 3 decades. This system has been well documented and consists of many integrated modules both to support the clinical functions of a medical center as well as its ancillary functions. Every piece of patient datum has many associated variables. These include when the datum was collected; how it was collected (by person or by machine); changes if it was edited; and who displayed or printed the data. The hospital’s EHR allows hospital and community-based clinicians and other providers to schedule patient visits; enter and review the clinical narrative; order tests and prescribe medications; and review laboratory results, reports for radiographic studies and other testing. Audit trails for all data entry and viewing are maintained. Included in these logs is information regarding user identity, the class of information accessed and a time of viewing/entry. During the time period of this study, computerized provider order entry was available for use in maternal but not newborn care. Similarly electronic note entry was available for mothers and NICU patients but not well newborns.

Population

This study includes deliveries occurring during the period between January 1, 2010 and December 31 2010 at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. BIDMC is a 600-bed major teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. There are >5,000 deliveries/year at BIDMC, and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology has 8 maternal-fetal medicine specialists and over 60 obstetricians serving BIDMC and a network of 7 community hospitals offering maternity services. The medical center has a state-of-the-art Level III Neonatal Intensive Care Unit with 48 intensive and intermediate care beds (level IIIB designation) with ∼800 admissions per year. Its average daily census is 37, and it is staffed by more than 80 clinical nurses, 8 masters-prepared neonatal nurse practitioners, 11 neonatal respiratory therapists, 14 board-certified neonatologists, and 20 neonatal-perinatal fellows. Children’s Hospital Boston, also located within the Longwood medical complex, provides a full range of pediatric subspecialty support. Post-discharge care of newborns is generally not provided at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

We created a socio-centric bi-partite network derived from audit trails of entry and lookups of maternal information. In this network, patients and providers represented the two node types. Using the institution’s master provider index, we categorized each individual into one of 5 provider groups as follows; 1) Nursing Professional (i.e. registered nurses, nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, and nurse midwifes), 2) Attending Physicians, 3) Medical Trainees (i.e. fellows, residents and medical students), 4) Other Clinicians (i.e. Respiratory, Occupational and Physical Therapists) and 5) Other Clinical and Administrative Support.

Patient-provider care interactions, as identified through audit log entries, served as the undirected edges in this network. For mothers, we considered all EHR access that occurred during a period defined to include peri-conceptual through post-partum care. This period extended from 314 days prior to delivery (e.g. 30 days prior to estimated last menstrual period for a term gestation) through the 6-week post-partum visit. For newborns, the period extended from birth through ultimate discharge home. The timing of EHR access was stored as an edge attribute. We combined this with information from the ADT system to characterize each provider-maternal edge as occurring during either an inpatient or outpatient encounter.

Human Subjects

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Committee on Clinical Investigations at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Results

During the one year study period, 4,498 mothers delivered a total of 4,678 babies. Routine newborn care was required by 4130 infants while 548 required intermediate or intensive care.

Individuals involved in maternal care

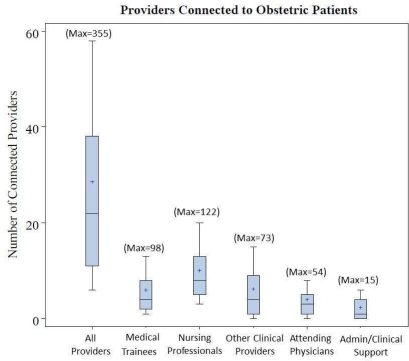

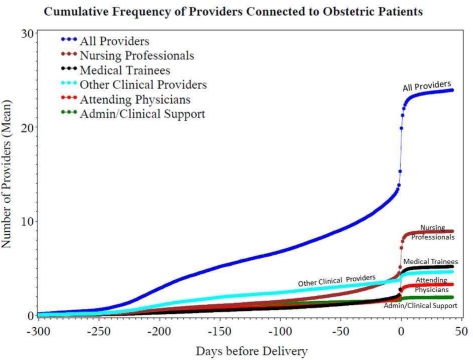

From our bi-partite patient-provider network, we calculated degree centrality to identify the total number total of individuals with connections to each patient through the EHR. During the peri-conceptual period through postpartum visit, 4,785 distinct individuals providers connected to at least one maternal record. Of these, 4,010 providers accessed maternal records for clinical reasons including providing clinical care, cross-coverage or oversight of medical trainees. These reasons for access are requested daily of each user at the time of initial access of a given patients record. As seen in Figure 3, the number of individuals accessing a individual mother’s record for clinical reasons ranged from 1 to 355 across the delivery population. Nursing professionals and attending physicians were the most frequently connected providers. Figure 4 demonstrates the time distribution of provider connections. Most clinical access (71.9%) occurred during outpatient encounters while the cumulative number of connected providers showed rapid increases at the time of delivery. For nursing professionals, this rise in connections began earlier.

Figure 3:

Number of unique providers involved in maternal care during the perinatal through postnatal period. Whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentile of the number of connected providers Boxes represent the interquartile range. + = mean.

Figure 4:

Cumulative Number of providers connected to individual obstetric patients. Series represent the mean number of connected providers. Delivery day is represented by Day 0 on the horizontal axis.

As would be expected in this high risk obstetric service, attending physicians were not limited to obstetricians, but also consulting services such as infectious diseases, surgery, endocrinology and cardiology. Figure 3, shows the categories of individuals accessing maternal record distribution of individuals engaged in episodes of clinical interactions with others as determined from audit logs within the online medical record and laboratory information systems

Individuals involved in newborn care

Among newborns who require only routine care, hospitalizations are of relatively low intensity and short duration. We found smaller numbers of patient-provider connections in this group. Generally well newborns were connected to 3 nursing professionals (first and third quartiles; 2,4). Interestingly, 74.5% of well newborns were not connected to an attending physician. This is likely reflective of the relatively low computer usage among community based pediatric providers who may rely on nursing and other staff to retrieve information. In addition, during the time of this study, computerized provider order entry was not available in the care of well newborns unlike adult care areas and the neonatal intensive care unit. Thus these highly sensitive links are not available for this population of patients.

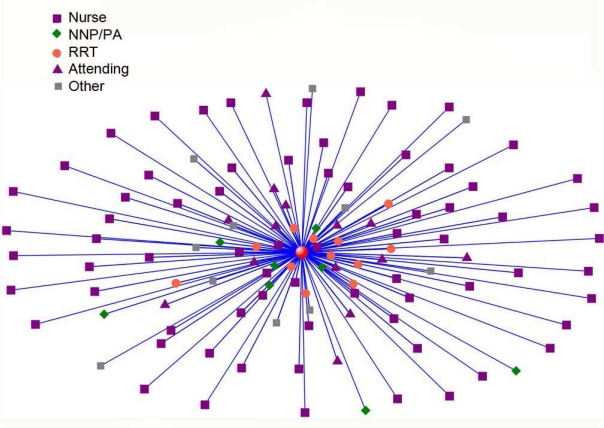

Understanding the structure of healthcare teams

We applied several approaches to understanding the structure of team structure. As seen in Figure 5, patient centric views of care team structure can quickly identify those providers who are most closely associated with a patient’s care.

Figure 5:

In this patient centered NICU provider network the patient is represented by red sphere in center of figure. Providers are represented by other icons (see key). Providers with largest number of ties to patient in this progress note based network are closest to patient.

Other network projections can also be created create such as the handoff network seen in Figure 6. Here, nodes represent the nurses involved in a single patient’s care. Edges represent the handoffs that occurred. The directionality of handoffs can be represented by directed edges and the number of handoffs between clinician pairs can be represented by edge weights (not shown here). In addition, the importance of individual nodes (i.e. clinicians) in the handoff network can be quantified using network analytic measures such as node and network betweenness centrality. Both measures carry values that range from 0 to 1. The former can be viewed as a measure of an individual nodes importance to information flow through the network with higher values being associated with greater node importance. Network betweenness centrality quantifies the dispersion of each nodes relative influence on communication within the network. Higher values are seen in networks which are dominated by a smaller number of important nodes. In other work, we have found standard metrics such a group degree-centrality (a measure of the connectedness) between two groups of nodes to be valuable in studies of nosocomial infection spread[35]. In addition, we have developed novel metrics such as the Mean Repeat Caregiver Interval (MERCI) that can be applied to handoff networks and provides a valid and valuable measure of care continutity[36].

Figure 6:

In this nursing handoff network, each node represents a nurse involved in this particular patient’s care. Edges represent the handoffs that occurred between providers. Node size is proportional to that nodes betweenness centrality, a measure of the node’s importance to information flow.

Discussion

Providing high quality health care requires effective collaboration between patients, families and a large and diverse network of clinical providers. Network analysis applied to health care teams provides better understanding of team structure and its dynamic nature. Our use of routinely available data from the electronic health record enables the real time applications that monitor the health not just of patients, but also the teams that provide their care. We believe our approach will allow more routine use of these techniques in quality improvement and research endeavors.

To our surprise a large number of providers participate in a mother’s care. Over 25% of individuals who have access to the BIDMC clinical information system accessed at least one maternal record during the course of a single calendar year to support clinical care. We observed one patient care team that included over 300 clinicians.

Furthermore, these interactions were not restricted to inpatient stays, but also occurred during routine obstetric outpatient care. In fact the majority of information access occurred during the outpatient period.

These results suggest that the approaches we have used to understand team structure and function in the clinically intense and data rich environment of the intensive care unit[35–36] are applicable to other domains of in-patient and out-patient care clinical care.

We have begun to apply the Digital Crumbs paradigm to understanding the impact of team structure on outcomes such as patient/family satisfaction with care, the spread of nosocomial colonization with organisms such as methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. In recently funded work, we are investigating how an individual patient’s risk of clinical deterioration and subsequent need for RRT activation is a function not only of patient level characteristics, but also the complex set of connections that exist between patients, their care and the teams that provide this care. Expansion of this work to understand the dynamics of team communication across transitions in care is likely to be valuable.

Conclusion

The application of network analytic methods to metadata contained within an electronic health record represents a powerful technique to understand the health care teams that develop around individual patients and within operational units and institutions. We believe that these methods will find use in understanding the role that differences in team structure may play in determining outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part with funding from the National Library of Medicine (1G08LM010703-01) and the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology (CIMIT, U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity W81XWH-09-2-0001).

The authors wish to thank Carolyn Conti and Caryn Franklin for their support in this project.

References

- 1.Barabási A-L. Linked : how everything is connected to everything else and what it means for business, science, and everyday life. New York: Plume; 2003. p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barabasi AL. Network medicine--from obesity to the “diseasome”. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):404–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazer D, et al. Social science. Computational social science. Science. 2009;323(5915):721–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1167742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitfield J. Collaboration: Group theory. Nature. 2008;455(7214):720–3. doi: 10.1038/455720a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabasi AL. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature. 2000;406(6794):378–82. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trudeau RJ. Dover books on advanced mathematics. New York: Dover Pub; 1993. Introduction to graph theory; p. x.p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman LC. Models and methods in social network analysis. In: Carrington PJ, Scott J, Wasserman S, editors. Structural analysis in the social sciences 27. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge; New York: 2005. pp. 248–269. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nooy Wd, Mrvar A, Batagelj V. Structural analysis in the social sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek; p. xxvii.p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Social Network Visualization in Epidemiology 19 (1): 5–16 (2009) Norwegian Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;19(1):5–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizruchia MS, Marquis C. Egocentric, sociocentric, or dyadic?: Identifying the appropriate level of analysis in the study of organizational networks. Social Networks. 2006;28(3):187–208. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasserman S, Faust K. Structural analysis in the social sciences 8. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. Social network analysis : methods and applications; p. xxxi.p. 825. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman MEJ. Networks : an introduction. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. xi.p. 772. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helleringer S, Kohler HP. Sexual network structure and the spread of HIV in Africa: evidence from Likoma Island, Malawi. AIDS. 2007;21(17):2323–32. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328285df98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen S, et al. Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA. 1997;277(24):1940–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorin AA, et al. Weight loss treatment influences untreated spouses and the home environment: evidence of a ripple effect. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(11):1678–84. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowe CF, et al. Effects of a peer modelling and rewards-based intervention to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(3):510–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(1):132–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews JA, et al. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychol. 2002;21(4):349–57. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(21):2249–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Dev Psychol. 1997;33(5):834–44. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christakis NA. Health care in a web. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shortell SM, LoGerfo JP. Hospital medical staff organization and quality of care: results for myocardial infarction and appendectomy. Med Care. 1981;19(10):1041–55. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shortell SM, et al. The role of perceived team effectiveness in improving chronic illness care. Med Care. 2004;42(11):1040–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shortell SM, et al. An empirical assessment of high-performing medical groups: results from a national study. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(4):407–34. doi: 10.1177/1077558705277389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shortell SM, Singer SJ. Improving patient safety by taking systems seriously. JAMA. 2008;299(4):445–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shortell SM, et al. The performance of intensive care units: does good management make a difference? Med Care. 1994;32(5):508–25. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA. 2004;291(10):1246–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guimera R, et al. Team assembly mechanisms determine collaboration network structure and team performance. Science. 2005;308(5722):697–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1106340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bleich HL, Safran C, Slack WV. Departmental and laboratory computing in two hospitals. MD Comput. 1989;6(3):149–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safran C, Slack WV, Bleich HL. Role of computing in patient care in two hospitals. MD Comput. 1989;6(3):141–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safran C, Sands DZ, Rind DM. Online Medical Records: A Decade of Experience. Method Inform Medicine. 1999;38:308–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safran C, et al. Protection of confidentiality in the computer-based patient record. MD Comput. 1995;12(3):189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loscalzo J, Kohane I, Barabasi AL. Human disease classification in the postgenomic era: a complex systems approach to human pathobiology. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:124. doi: 10.1038/msb4100163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geva A, Brodie-Wright S, Baldini L, Smallcomb J, Safran C, Gray JE. Spread of MRSA in a Large Tertiary NICU over a 6-Year Period: A Network Analysis. 2011. Manuscript under Review, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Gray JE, et al. Network analysis of team structure in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):e1460–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]