Abstract

The ability to predict early in the course of treatment the response of breast tumors to neoadjuvant chemotherapy can stratify patients based on response for patient-specific treatment strategies. Currently response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is evaluated based on physical exam or breast imaging (mammogram, ultrasound or conventional breast MRI). There is a poor correlation among these measurements and with the actual tumor size when measured by the pathologist during definitive surgery. We tested the feasibility of using quantitative MRI as a tool for early prediction of tumor response. Between 2007 and 2010 twenty consecutive patients diagnosed with Stage II/III breast cancer and receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy were enrolled on a prospective imaging study. Our study showed that quantitative MRI parameters along with routine clinical measures can predict responders from non-responders to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The best predictive model had an accuracy of 0.9, a positive predictive value of 0.91 and an AUC of 0.96.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among American women with a long-term mortality of 25%1. Neoadjuvant or pre-operative chemotherapy, previously limited to patients with locally advanced breast cancer, is currently being used in patients with earlier stages of disease2–7. There are several potential advantages to neoadjuvant chemotherapy including the following:

The early initiation of systemic therapy in a patient population that carries a high risk of distant disease failure can contribute to improved outcomes.

The original tumor size can be reduced to allow patients who would have otherwise required mastectomy to be considered for breast conservation therapy.

The intact tumor can provide an in-vivo measure of tumor response to chemotherapeutic combinations.

The current approach to measure treatment response is based on gross tumor measurements by physical examination, ultrasound, mammogram or conventional magnetic resonance imaging of the breast. These methods have very little correlation with each other or to the actual tumor size when measured at time of definitive surgery8, 9. Breast ultrasound is superior to mammography in estimating pathologic residual disease with receiver operating characteristic of 0.78 vs. 0.74, respectively. The only reliable measure of outcome has been the absence of tumor at time of definitive surgery or pathologically confirmed complete response (pCR). Patients who achieve a pathologic complete response to chemotherapy have improved disease-free and overall survival10. Therefore, pCR can be used as a surrogate marker for survival and potentially can allow us the opportunity to test novel combinations of agents. Instead of having to wait for years to determine the disease-free survival or survival benefit of a particular novel combination, pCR can be measured immediately after definitive surgery. This is therefore, the ideal setting in which to perform clinical trials of new agents. Unfortunately, pCR rates are usually in the 15% range11 and therefore, clinical trials which are evaluating a variety of neoadjuvant regimens require a large number of patients to have sufficient events (number of patients with pCR) to have the power to detect differences in therapeutic regimens. Moreover, pCR implies that all of the treatment has already been completed and the patient has gone to surgery.

Although mammography and ultrasound imaging play a critical role in the detection and diagnosis of breast cancer, there are currently no adequate radiological methods for assessing the response of tumors to treatments to guide clinical decisions. The development of appropriate methods of tissue characterization that could be applied early in the course of treatment to assess tumor response would allow clinicians to tailor therapy for an individual patient based on each patient’s response to a particular agent. In addition, such (surrogate) imaging biomarkers would be of considerable value in clinical trials of new drugs.

Although changes in markers of proliferation and apoptosis could provide a meaningful measure of treatment response, serial biopsies are invasive for the patient and are subject to errors of sampling. Serial clinical MRI scans done during the course of chemotherapy has proven less successful than was initially hoped12. On the other hand, specialized methods, including dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) and diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) have advanced to the point where they provide unique measurements of tissue properties that are highly relevant for assessing tumor progression and responses13. In DCEMRI, lesions display characteristic enhancement patterns which have been shown to change reliably following treatments and are related to the extent and integrity of the tumor vasculature14, 15. In DW-MRI, increased water apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values within tumors following a treatment regimen correlates with reduced tissue cellularity16.

In this study, we describe a new approach to the identification of novel imaging biomarkers for assessing the response of breast cancer to treatment. Integrating the quantitative, non-invasive imaging modalities of DCE-MRI and DW-MRI will provide a unique and comprehensive approach for breast tumor characterization. Furthermore, we perform the MRI studies at the high-field strength of 3T, allowing for increased spatial resolution, improved signal-to-noise, and reduced scan times compared with 1.5T clinical scanners. The development of these improved imaging techniques would allow us to obtain serial MRI scans early in the course of treatment that could be used to predict pathologic response.

While conventional mammography is useful as a screening tool for detecting breast lesions, many women at risk for cancer have radio dense breast tissue which limits the sensitivity and specificity of x-ray methods. Furthermore, conventional imaging methods do not provide information on soft tissues, the molecular status of the tumor, nor their response to therapy. Finally, the 2D nature of planar X-ray mammography makes it difficult to localize a potentially complex 3D structure of a lesion thus making it very difficult to employ in quantitative longitudinal studies. Although serial biopsies may be obtained to measure changes at the cellular level, the spatial sampling may be poor and the results misleading. Clinical judgment using physical examination, mammograms and ultrasound to measure short-term treatment effects have a high inter-observer variability and are prone to error. A non-invasive imaging modality which can reliably assess tumor response would greatly improve clinical breast cancer care.

The overall goal of this study is to synthesize DCE-MRI and DW-MRI with standard clinical information to predict the response of breast cancer patients to neoadjuvant chemotherapy after the first cycle of treatment.

Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI and breast cancer

MRI contrast agents (CAs) are pharmaceuticals administered to patients that are designed to increase the contrast between different tissues by changing a tissue’s inherent T1 and/or T2 relaxation rates. The most common MRI CAs are gadolinium-chelates such as Gd-DTPA. These agents are used in as many as 40% of magnetic resonance (MR) exams and are considered quite safe17. In a typical DCE-MRI imaging session, a region of interest (ROI) is selected for study (e.g., a tumor locus), and MR images are collected before, during, and after a CA is injected into the antecubital vein of a patient. Each image corresponds to one time point, and each pixel in each image set then gives rise to its own time course (one signal intensity per time point) which can then be analyzed with a mathematical model. Values of various pharmacokinetic and intrinsic tissue properties may then be extracted by fitting these time courses to produce parametric images. Model parameters, which describe the CA movement across the vascular endothelium, are expressed in typical physiological parameters: blood flow (perfusion), vessel wall permeability, vessel surface area, and extracellular extravascular volume fraction.

Diffusion-weighted MRI and breast cancer

The microscopic thermally-induced behavior of molecules moving in a random pattern is referred to as self-diffusion or Brownian motion. The rate of diffusion in cellular tissues is described by means of an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), which largely depends on the number and separation of barriers that a diffusing water molecule encounters. MRI methods have been developed to map the ADC, and in well-controlled situations the variations in ADC have been shown to correlate inversely with tissue cellularity18. It has recently been shown that exposure of tumors to both chemotherapy and radiotherapy consistently leads to measurable increases in water diffusion in cases of favorable treatment response16, 19. Preliminary studies in humans have shown that ADCs in both normal tissue and benign lesions are significantly higher when compared to those found in malignant breast lesions20, 21. In recent studies, Mohsin et al22 and Stearns et al23 show that the parameters measuring blood flow and vessel “leakiness” correlated significantly with patient responses after one course of chemotherapy. We believe using more sophisticated mathematical analyses of DCE-MRI data, like those used in our study, can significantly increase the sensitivity of measuring response to breast cancer treatment. Furthermore, recent results in rodents have shown a two-fold increase in ADC values in tumors following treatment16, 19. Our previous study24 which was also the first study to combine both quantitative DCE-MRI and DW-MRI in the longitudinal assessment of breast cancer treatment response showed that ADC values increased approximately 25% after successful treatment.

Predictive modeling using an informatics approach

The field of Biomedical informatics provides a framework for the best use of biomedical information, data and knowledge for problem solving and decision making25. Biomedical informatics approaches are increasingly being employed for predictive modeling in cancer evaluation. Good reviews of the application of predictive modeling methods in cancer can be found in26 and27. Machine learning (ML) methods that develop models from data by searching through the model and parameter space have been embraced by the biomedical informatics community for predictive modeling and decision making in biomedicine. For example, ML methods have been successfully employed for breast cancer screening28, to discriminate malignant and benign microcalcifications29, for predicting breast cancer survival30 and to model prognosis of breast cancer relapse31. Machine learning methods have been shown to substantially improve (15–25%) the accuracy of cancer susceptibility (risk) and cancer outcome (prognosis) prediction in various types of cancers including breast cancer26. Since machine learning methods can scale up and build models from large and complex datasets they are appropriate for model building using a combination of clinical and imaging data. Researchers have started looking into the application of machine learning techniques utilizing image data for predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer32. Using data from 96 patients with tumor sizes assessed by PET at various stages of their chemotherapy treatment Gyftodimos et al. demonstrated the efficacy of machine learning methods for differentiating low responders to treatment from high responders at an early stage of treatment32.

Methods

In this section we describe the dataset, the predictive modeling algorithms that we used and the experimental methods employed for generating the results presented in this paper.

Dataset Generation and Eligibility Criteria

Patient Selection

All patients with Stage II/III breast cancer who were undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy at our institution (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA) are offered the opportunity to also participate in an imaging study. This is an IRB approved prospective study of breast MRI scans done in patients who are undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. All enrolled patients provided informed consent and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center. All patients had pathologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the breast. Core needle biopsy was used to establish the diagnosis as well as to perform full immunohistochemical analysis of the tumor including estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER-2). All patients had a clip placed to mark the location of the tumor prior to initiating chemotherapy. This clip was placed even in those patients expected to require a mastectomy to aid the pathologist to identify the tumor bed especially in patients who underwent complete pathologic response. This clip also guided the surgeon for breast conservation cases especially in patients who had a complete clinical response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Pretreatment clinical staging was based on physical examination, mammogram, ultrasound, CT scans of the chest/abdomen/pelvis and/or PET scans. All patients had pretreatment sentinel node evaluation which was also incorporated into the preclinical stage. Our study is based on 20 consecutive patients enrolled between 1/3/2007 and 8/4/2010.

Pretreatment Clinical Stage

Pretreatment clinical T-stage was based on all available clinical data using physical examination, mammography and ultrasound. The pretreatment tumor size was based on the clinical finding that was judged to be the most accurate for that particular case. Pretreatment N-stage or clinical nodal status was based on all available data prior to the initiation of chemotherapy and included physical examination, ultrasound, pretreatment fine needle aspiration of the axillary nodes and pre-treatment sentinel lymph node evaluation. Any patient who had evidence of distant metastases was not eligible for this study. Pretreatment clinical stage was defined using the AJCC 7th edition33.

The chemotherapy used could be either standard of care agents or novel agents on a clinical trial. The choice of chemotherapy was left to the discretion of the treating medical oncologist. A research MRI scan was performed before the initiation of any chemotherapy, 10–14 days following the start of treatment and just prior to definitive surgery. The findings were then correlated with pathologic findings at the time of definitive surgery.

Treatment

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor type 2 receptor (HER2) negative tumors usually consisted of doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide administered in a dose-dense schedule every 2 weeks for 4 cycles followed by weekly paclitaxel x 12 cycles.

A minority of patients were treated with doxorubicin and Docetaxel.

HER2 positive patients were treated with trastuzumab-based regimens. Most commonly this would be paclitaxel, carboplatin and trastuzumab.

Patients with triple negative disease participated on an ongoing clinical trial that combined cisplatin, paclitaxel and were randomized to either Everolimus (RAD001) or placebo.

All patients who had ER+ or PR+ disease went on to receive planned 5 years of hormonal therapy.

Patients who progressed on chemotherapy went on to surgical resection.

We selected 12 clinical variables including age, clinically estimated tumor size and node parameters obtained before initiation of neoadjuvant therapy for predictive modeling.

Surgery

Approximately one month following the last cycle of neoadjuvant treatment all patients went on to definitive surgery. Surgery consisted of either mastectomy or lumpectomy. Patients with pretreatment sentinel nodes that were positive also had axillary nodal evaluation.

MRI Techniques

DW-MRI and DCE-MRI were performed using a Philips 3T Achieva MR scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) prior to and after one cycle of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A 4-channel receive double-breast coil covering both breasts was used for all imaging (In-vivo Inc., Gainesville, FL). DW-MRIs were acquired with a single-shot spin echo (SE) echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence in three orthogonal diffusion encoding directions (x, y, and z), with two b-values (0 and 600 s/mm2), FOV = 192×192 (unilateral), and an acquisition matrix of 96×96. SENSE parallel imaging (acceleration factor = 2) and spectrally-selective adiabatic inversion recovery (SPAIR) fat saturation were implemented to reduce image artifacts. Subjects were breathing freely with no gating applied. The patient DWIs consisted of 12 sagittal slices with slice thickness = 5 mm (no slice gap), TR = 2255 ms, TE = ‘shortest’ (43, 48, or 51 ms), diffusion time = 20.7, 23.2, or 24.9 ms, and diffusion gradient duration = 11.6, 10.6, or 10.2 ms, respectively, NSA = 10, for a total scan time of 2 min and 42 s.

Data for a T1 map were acquired with a 3D RF-spoiled gradient echo multi-flip angle approach with a TR\TE of 7.9\1.3 ms and ten flip angles from 2 to 20 degrees in two degree increments. The acquisition matrix was 192×192×20 (full-breast) over a sagittal square field of view (22 cm2) with slice thickness of 5 mm, one signal acquisition, and a SENSE factor of 2 for an acquisition time of just under 3 minutes. The dynamic scans used identical parameters and a flip angle of 20°. Each 20-slice set was collected in 16.5 seconds at 25 time points for approximately seven minutes of scanning. A catheter placed within an antecubital vein delivered 0.1 mmol/kg of Magnevist at a rate of 2 mL/sec. after the acquisition of three baseline dynamic scans for the DCE study. The diffusion, T1, and dynamic image volumes were all acquired with the same center location, making them inherently co-registered.

Image parameters were obtained in an automated way using both DW and DCE MRI techniques using standard methods (see for example34). Imaging data was acquired at two time points: (1) just before initiation of the first cycle of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and (2) immediately following the completion of the first cycle of chemotherapy. The parameters of interest include the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC, from DW-MRI data); the ADC reports on tissue cellularity. DCE-MRI reports on tissue vascular parameters include the volume transfer constant (Ktrans), and the plasma fraction (νp). DCE-MRI also reports on the volume of extravascular extracellular space (νe), and the average lifetime of a water molecule inside a cell (τi). Delta values (differentials) for the image parameters between the pre and post neoadjuvant cycle one treatment (denoted by lower case t1 and t2) were also computed.

Post Treatment Pathologic Assessment:

Pathologic evaluation of the tumors were performed at time of definitive surgery. Tumors were classified as having pCR if there was no invasive cancer present in either the breast or lymph nodes. A small amount of residual tumor cells (<5 mm) were defined as near pCR. Pathologic ypTNM staging was defined as per the AJCC 7th edition33. Pathologic Complete Response (pCR) was defined as follows: no residual viable tumor on histologic analysis on both breast specimen and axillary lymph nodes. This was our gold standard outcome variable.

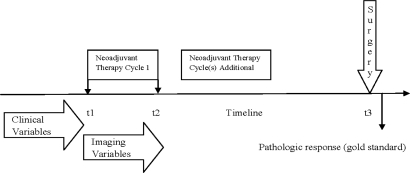

We created three datasets (1) Imaging with 13 variables plus the outcome variable (pCR yes/no), (2) Clinical with 12 variables plus the outcome variable and (3) Imaging plus Clinical consisting of 25 variables in addition to the outcome variable. A list of all the imaging and clinical variables with a short description is included in the Appendix (Table 4). All the three datasets were used for predictive modeling. As mentioned earlier once a diagnosis of breast cancer is made and for patients who are considered to benefit from neoadjuvant therapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is initiated which is followed approximately 1 month later by definitive surgery. Figure 1 provides the timeline with t1 denoting the start of cycle 1 of neoadjuvant therapy, t2 the end of cycle 1 of neoadjuvant therapy and t3 denotes the time of definitive surgery. The timeline of imaging variables starts just prior to t1 and ends immediately after t2 whereas all the clinical variables used in our modeling are pre t1 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Temporal relationship of clinical and imaging parameters to treatment and assessment of its response.

Algorithms

We defined the predictive modeling task using machine learning methods as follows: can we predict if the patient has pathological complete response or not given imaging measurements of this patient from t1 to t2 and clinical variables no later than t2? We used a representative set of machine learning and feature selection algorithms for our predictive modeling task. Three linear classifiers (Gaussian Naïve Bayes35, Logistic Regression and Bayesian Logistic Regression), two decision tree based classifiers (CART36 and Random Forests37), one kernel based classifier (Support Vector Machine38) and one rule learner (Ripper39) were used. To increase predictive performance, feature (attribute) selection algorithms are often used to select a subset of the features that are highly predictive of the class. By selecting a small number of the most relevant features (or by eliminating many irrelevant features), one is able to reduce the risk of over fitting the training data and often produce a better overall model. Three state of the art feature selection methods were used in our experiments: HITON-MB40, Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization with a maximum number of ten features output (GS-10)41, 42, and BLCD-MB40, 43.

We used a modified version of the Bayesian Logistic Regression (BLR) described in44. BLR is similar to the basic Logistic Regression in the regression step but uses a Bayesian modeling framework to captures the nonlinear relationships between variables and the outcome. We assumed that all continuous variables have a Gaussian distribution, and the variables were evaluated based on the parametric distribution conditional on the outcome variable. For binary variables, the class conditional probability was considered along with non-informative priors. The log odds ratio for each independent variable was incorporated into the BLR model. The logistic function is defined below for computing the posterior probability of positive class non pCR (non-responders of neoadjuvant treatment in our case) given the combination of all features:

where n is the number of features and c = log P(nonPCR)/P(PCR) is a prior log odds ratio. We include non-informative priors to estimate the probability of each class. The ith feature is used to derive a transformed feature f(vi) via nonlinear Bayesian modeling:

where P(vi | nonPCR) or P(vi | PCR) is computed from the probability density function learned from Gaussian distribution of continuous feature vi, in the training samples with label nonPCR or PCR. If vi is a discrete or binary variable, P(vi | nonPCR) or P(vi | PCR) is estimated as a conditional probability distribution based on the counts as well as the non-informative prior. The parameters b and w are learned from the training data by the L2-regularized Logistic Regression45 which solves the following optimization problem:

where C is the penalty parameter or cost that controls the complexity of the model and was set to 1 in our experiments. The parameter wi represents the weight of contribution of feature i, with higher weight features having a greater effect.

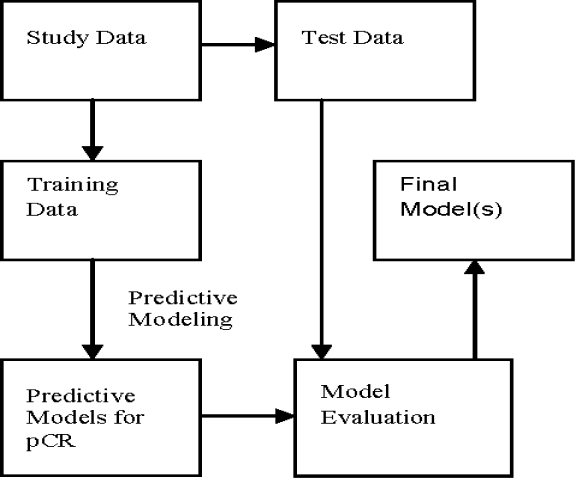

Because of the small sample size (n=20) we implemented the leave one out (n-fold) cross validation method which uses one sample in the test set and all the others for training. This was repeated twenty times using a different test sample for each run. Predictive models were built using the training samples and evaluated on the test sample. The general schema for predictive model building is shown in Figure 2. For each test sample we output the probability of the positive class and use a threshold (0.5) to classify the sample as positive/negative class. To evaluate the probability output, we used AUC score (area under ROC curve); to evaluate the binary output, we used accuracy, precision (positive predictive value), recall (sensitivity) and specificity.

Figure 2:

A General Schema for Predictive Model Building and Evaluation. pCR: Pathological Complete Response.

Results

Three datasets were used for prediction (with and without feature selection) and the results for imaging, clinical and imaging plus clinical datasets are shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Using only imaging data CART had the best performance (accuracy and AUC of 0.7) with no feature selection (see Table 1).

Table 1:

Leave-One-Out Prediction Result using Imaging Data. No-FS: No feature selection; GS-10: Gram-Schmidt feature selection; AUC: Area under the ROC curve.

| Imaging Data (13 variables) | Accuracy | Precision | Recall/Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 |

| Naïve Bayes | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.40 |

| CART | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.69 |

| SVM | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.70 |

| RF | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.65 |

| LR | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.49 | 0.53 |

| Bayesian LR | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.65 |

Table 2:

Leave-One-Out Prediction Result using Clinical Data

| Clinical Data (12 variables) | Accuracy | Precision | Recall/Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 |

| Naïve Bayes | 0.55 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.72 | 0.74 |

| CART | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.11 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.56 |

| SVM | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| RF | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| LR | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| Bayesian LR | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 0.71 |

Table 3:

Leave-One-Out Prediction Result using both Imaging Data and Clinical Data

| Imaging + Clinical Data (25 variables) | Accuracy | Precision | Recall/Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 | No-FS | GS-10 |

| Naïve Bayes | 0.55 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.18 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.69 |

| CART | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.68 |

| SVM | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.56 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| RF | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.71 |

| LR | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.81 |

| Bayesian LR | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.96 | 0.82 |

Using only clinical data LR and Bayesian LR had the best performance with accuracy, recall and AUC of 0.7 or better. The best AUC of 0.77 was obtained by LR when combined with the GS-10 feature selection algorithm (see Table 2). Combining imaging and clinical data Bayesian LR had the best performance with an accuracy of 0.9, precision and recall of 0.91 and an AUC of 0.96 (see Table 3).

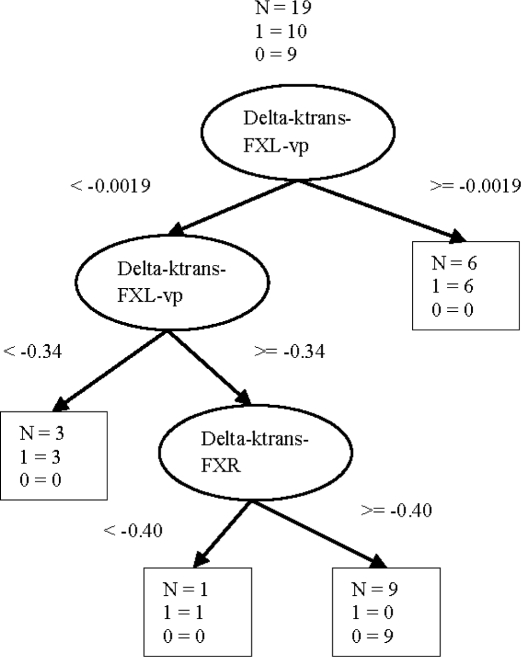

Figure 3 shows a representative CART tree obtained using only the imaging variables. Out of the twenty trees obtained based on the n-fold cross validation the same tree structure shown in Figure 3 was obtained with fourteen folds.

Figure 3.

A representative Cart tree for predicting neoadjuvant treatment response.

Discussion and conclusion

Breast cancer continues to take its toll in spite of recent advances in chemotherapy. A key to better prediction of treatment outcome is the early identification of responders to a specific treatment protocol. The use of the traditional clinical parameters of anatomic size alone as a means of evaluating treatment response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not provide any information on the early changes that occur at the cellular level long before actual changes in anatomic size. Imaging studies that can provide such functional data early on in a patient’s treatment would allow clinicians the opportunity to change the type of chemotherapy being used and thereby allow for a more personalized approach to cancer therapy instead of the current “one size fits all” approach. If we could identify non responders within a week of the first cycle of chemotherapy, we could use alternative agents instead of subjecting the patient to the side effects of therapies that are destined to fail. Such imaging biomarkers need to be tested against known clinical outcome measures such as pathologic complete response in larger patient datasets before they can be utilized in the clinical setting.

There is a real need for new, effective and preferably non-invasive or minimally invasive approaches to predict treatment response. Conventional high resolution anatomical MR imaging is appropriate for diagnosis but not particularly useful for monitoring response to treatment. Functional MR imaging that captures changes in metabolism and perfusion that occur before morphological changes become evident can be valuable in this setting46. This fact is not lost on the MR community. Unfortunately, two of the most well performed investigations into using quantitative MRI to predictive therapy response yielded conflicting results. Ah-See et al. showed that Ktrans was the best predictor of therapy response; furthermore, the authors showed that changes in tumor size did not predict response47. This is important because it provides an example of a functional imaging technique (DCE-MRI) that outperforms conventional morphological imaging. However, Yu et al. showed that changes in tumor volume outperformed DCE-MRI parameters48. Clearly, more work is needed in this important field.

In our study, predictive modeling approaches using quantitative MRI parameters show promise in distinguishing responders from non-responders after the first cycle of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Though both imaging and clinical parameters separately had similar overall performance, using imaging and clinical variables together boosted the performance of Bayesian LR considerably resulting in an accuracy of 0.9 and an AUC of 0.96. In general models generated using no feature selection performed better. This implies that the 13 imaging and 12 clinical variables used in our study were relevant attributes.

Predicting pathological complete response with a high degree of certainty following cycle 1 of neoadjuvant therapy will enable physicians to stratify patients based on response and channel early non-responders to alternate protocols of therapy. Because of our modest sample size we were not able to test response based on the specific chemotherapeutic agent(s). Likewise, we did not attempt to build patient specific predictive models using a subset of patients to tailor treatment more effectively.

To date, the most complete study employing quantitative DCE-MRI before and after two cycles of therapy to assess the response of breast tumors to neoadjuvant chemotherapy was performed by Ah-See et al47. In their study of 28 patients, they achieved, using the parameter Ktrans, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the ROC curve of 0.94, 0.82, and 0.93, respectively, in identifying pathological complete response. This translates into correctly identifying 94% of the nonresponders and 73% of the responders.

Interestingly, a similar study by Yu et al reported different results48 in assessing the ability of tumor size, Ktrans and kep (=Ktrans/ve) to predict clinical response after one cycle of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in 29 patients with invasive breast cancer. The area under the ROC curve for differentiating nonresponders and responders was 0.88, 0.77, and 0.63 for tumor size, kep, and Ktrans, respectively. The authors concluded that early tumor size changes on MRI after one cycle of therapy provided the most accurate predictor in assessing response to this treatment regimen.

The fact that these two studies provide different answers to (essentially) the same clinical question underscore the importance of developing and validating quantitative methods of assessing the response of breast tumors to neoadjuvant chemotherapy early in the course of treatment. Although there are many studies that have used either serial MRI scans or clinical parameters to predict tumor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, our study is one of the few that has combined both clinical and imaging parameters to predict response to chemotherapy. This small cohort of 20 patients has served as our predictive model learning set. As the protocol continues to accrue patients, we plan to test the predictive ability of this model in a separate test set of patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health for funding through NCI 1R01CA129961, NCI P30 CA68485, and NCI 1U01CA142565.

Appendix

Table 4.

List of clinical and imaging variables used.

| Clinical Variable | Description | Imaging Variable | Key Term | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Age at the time of diagnosis | Delta ADC | Delta | t1, t2 difference |

| ER+ | Estrogen receptor | Delta Ktrans FXL | Ktrans | Pharmacokinetic transfer constant |

| PR+ | Progesterone receptor | Delta Ktrans FXLvp | FXL | Fast exchange limit |

| HER2+ | Human epidermal growth factor receptor | Delta Ktrans FXR | FXR | Fast exchange regime |

| Clinical Grade | Pretreatment clinical grade | Delta ve FXL | vp | Blood plasma volume fraction |

| Proliferative rate | Delta ve FXLvp | ve | Extravascular extracellular volume fraction | |

| Pre-treatment nodal status | Pathologically confirmed by fine needle aspiration or sentinel node evaluation | Delta ve FXR | ti | Intra cellular water lifetime of water molecule |

| Clinical-T | Pretreatment clinical size based on clinical findings judged most accurate for that case (physical exam, ultrasound, mammogram, conventional MRI) | Delta vp FXL | ||

| Clinical-N | Pretreatment nodal stage based on pathologically confirmed by fine needle aspiration of node or sentinel evaluation | Delta ti FXR | ||

| Pre-treatment clinical stage | Staging of the breast cancer prior to initiation of systemic chemotherapy | Ktrans t1 FXL | ||

| Pre-treatment physical exam | Longest diameter by physical exam (cm) | Ktrans t1 FXLvp | ||

| Pre-treatment longest diameter (ultra sound) | Longest dimension (cm) Clinical judgment is used to determine the modality most accurate for that case (physical exam, ultrasound, mammogram, conventional MRI) | Ktrans t1 FXR | ||

| Delta tumor volume |

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians:caac. 20107v1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Wolmark N, Wang J, Mamounas E, Bryant J, Fisher B. Preoperative chemotherapy in patients with operable breast cancer: nine-year results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. JNCI Monographs. 2001;2001:96. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher B, Brown A, Mamounas E, et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15:2483. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher ER, Jiping W, Bryant J, Fisher B, Mamounas E, Wolmark N. Pathobiology of preoperative chemotherapy: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) protocol B-18. Cancer. 2002;95:681–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rastogi P, Anderson SJ, Bear HD, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy: updates of national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project protocols B-18 and B-27. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher B, Bryant J, Wolmark N, et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on the outcome of women with operable breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16:2672. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Hage JA, van de Velde CJH, Julien JP, Tubiana-Hulin M, Vandervelden C, Duchateau L. Preoperative chemotherapy in primary operable breast cancer: results from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer trial 10902. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:4224. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keune JD, Jeffe DB, Schootman M, Hoffman A, Gillanders WE, Aft RL. Accuracy of ultrasonography and mammography in predicting pathologic response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. The American Journal of Surgery. 199:477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chagpar AB, Middleton LP, Sahin AA, et al. Accuracy of physical examination, ultrasonography, and mammography in predicting residual pathologic tumor size in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Annals of surgery. 2006;243:257. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197714.14318.6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuerer HM, Newman LA, Smith TL, et al. Clinical course of breast cancer patients with complete pathologic primary tumor and axillary lymph node response to doxorubicin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:460–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher B, Bryant J, Wolmark N, et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on the outcome of women with operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2672–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heywang-Koebrunner S, Murphy W, Gohagan J. Breasts. In: Bradley W, Stark D, editors. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1999. pp. 1401–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauppinen RA. Monitoring cytotoxic tumour treatment response by diffusion magnetic resonance imaging and proton spectroscopy. NMR in Biomedicine. 2002;15:6–17. doi: 10.1002/nbm.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes C, Padhani AR, Leach MO. Assessing changes in tumour vascular function using dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. NMR in Biomedicine. 2002;15:154–63. doi: 10.1002/nbm.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delille JP, Slanetz PJ, Yeh ED, Halpern EF, Kopans DB, Garrido L. Invasive Ductal Breast Carcinoma Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: Noninvasive Monitoring with Functional MR Imaging—Pilot Study1. Radiology. 2003;228:63. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2281011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galons JP, Altbach MI, Paine-Murrieta GD, Taylor CW, Gillies RJ. Early increases in breast tumor xenograft water mobility in response to paclitaxel therapy detected by non-invasive diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. Neoplasia (New York, NY) 1999;1:113. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shellock FG, Parker JR, Pirovano G, et al. Safety characteristics of gadobenate dimeglumine: Clinical experience from intra and interindividual comparison studies with gadopentetate dimeglumine. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging. 2006;24:1378–85. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson AW, Xie J, Pizzonia J, Bronen RA, Spencer DD, Gore JC. Effects of cell volume fraction changes on apparent diffusion in human cells. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2000;18:689–95. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(00)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KC, Moffat BA, Schott AF, et al. Prospective early response imaging biomarker for neoadjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13:443. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha S, Lucas Quesada FA, Sinha U, DeBruhl N, Bassett LW. In vivo diffusion weighted MRI of the breast: Potential for lesion characterization. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging. 2002;15:693–704. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo Y, Cai YQ, Cai ZL, et al. Differentiation of clinically benign and malignant breast lesions using diffusion weighted imaging. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging. 2002;16:172–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohsin SK, Weiss HL, Gutierrez M, et al. Neoadjuvant trastuzumab induces apoptosis in primary breast cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:2460. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stearns V, Singh B, Tsangaris T, et al. A prospective randomized pilot study to evaluate predictors of response in serial core biopsies to single agent neoadjuvant doxorubicin or paclitaxel for patients with locally advanced breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9:124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yankeelov TE, Lepage M, Chakravarthy A, et al. Integration of quantitative DCE-MRI and ADC mapping to monitor treatment response in human breast cancer: initial results. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2007;25:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shortliffe EH, Blois MS. The computer meets medicine and biology: Emergence of a discipline. In: Shortliffe EH, editor. Biomedical informatics: computer applications in health care and biomedicine. 3 ed. Springer; 2006. pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz JA, Wishart DS. Applications of Machine Learning in Cancer Prediction and Prognosis. Cancer Informatics. 2006;2:59–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vellido A, Lisboa PJG. Neural Networks and Other Machine Learning Methods in Cancer Research. LECTURE NOTES IN COMPUTER SCIENCE. 2007;4507:964. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nattkemper TW, Arnrich B, Lichte O, et al. Evaluation of radiological features for breast tumour classification in clinical screening with machine learning methods. Artificial Intelligence In Medicine. 2005;34:129–39. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei L, Yang Y, Nishikawa RM, Jiang Y. A study on several Machine-learning methods for classification of Malignant and benign clustered microcalcifications. Medical Imaging, IEEE Transactions on. 2005;24:371–80. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2004.842457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delen D, Walker G, Kadam A. Predicting breast cancer survivability: a comparison of three data mining methods. Artificial Intelligence In Medicine. 2005;34:113–27. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerez-Aragonés JM, Gómez-Ruiz JA, Ramos-Jiménez G, Muñoz-Pérez J, Alba-Conejo E. A combined neural network and decision trees model for prognosis of breast cancer relapse. Artificial Intelligence In Medicine. 2003;27:45–63. doi: 10.1016/s0933-3657(02)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gyftodimos E, Moss L, Sleeman D, Welch A. Analysing PET scans data for predicting response to chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Twenty-seventh SGAI International Conference on Innovative Techniques and Applications of Artifcial Intelligence 2007; Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edge SB, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. 7 ed. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yankeelov TE, Arlinghaus LR, Li X, Gore JC. The Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Biomarkers in Clinical Trials of Treatment Response in Cancer. pp. 16–25. In: Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Mitchell TM. Machine Learning: McGraw-Hill; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breiman L, Friedman JH, Olshen RA, Stone CJ. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont: Wadsworth; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breiman L. Random forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vapnik VN. Statistical learning theory. Wiley; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen WW. Fast effective rule induction. 1995. pp. 115–23. In: ICML; 1995;

- 40.Aliferis CF, Statnikov A, Tsamardinos I, Mani S, Koutsoukos XD. Local Causal and Markov Blanket Induction for Causal Discovery and Feature Selection for Classification. Part I: Algorithms and Empirical Evaluation. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2010a;11:171–234. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arfken G. Mathematical Methods for Physicists. 3 ed. Orlando: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guyon I, Elisseeff A. An Introduction to Variable and Feature Selection. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2003;3:1157–82. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mani S, Cooper GF. Causal discovery using a bayesian local causal discovery algorithm. Proceedings of MedInfo; Amsterdam: IOS; 2004. pp. 731–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saria S, Rajani AK, Gould J, Koller D, Penn AA. Integration of Early Physiological Responses Predicts Later Illness Severity in Preterm Infants. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2:48ra65. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan RE, Chang KW, Hsieh CJ, Wang XR, Lin CJ. LIBLINEAR: A library for large linear classification. The Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2008;9:1871–4. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Craciunescu OI, Blackwell KL, Jones EL, et al. DCE-MRI parameters have potential to predict response of locally advanced breast cancer patients to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and hyperthermia: A pilot study. International journal of hyperthermia: the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group. 2009;25:405. doi: 10.1080/02656730903022700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ah-See MLW, Makris A, Taylor NJ, et al. Early changes in functional dynamic magnetic resonance imaging predict for pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in primary breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14:6580. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu HJ, Chen JH, Mehta RS, Nalcioglu O, Su MY. MRI measurements of tumor size and pharmacokinetic parameters as early predictors of response in breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging. 2007;26:615–23. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]