Abstract

Although comparative effectiveness trials and nationally recognized clinical guidelines offer substantial guidance about ideal patient treatment, we remain largely uninformed about the patterns of care seen in everyday clinical practice. To address this gap in knowledge, we looked at registry-based data on breast cancer care at two neighboring healthcare institutions with a specific focus on whether organizational boundaries determine the physicians that a patient will see. From an initial patient-oriented data set, we developed a social network of physicians, modeling their interactions over the course of the provided treatments. Applying a mixture of visual and quantitative analyses to this network, we found evidence for strong intra-institutional ties and poignantly weak connections to physicians operating out of other healthcare centers.

Introduction

Despite growing amounts of data being collected in clinical settings through health IT, registries, and electronic health records (EHRs), we are unable to answer fundamental questions such as “What are the patterns of care in everyday clinical practice?” and “Why do these patterns vary?” In complex conditions such as mental disorders, heart disease, and cancer, we lack a particular understanding of how patient care is managed across specialists and institutions. Evidence suggests that this knowledge is a critical component in improving patient outcomes and that physician referral patterns form an important piece of the puzzle.1,2 To address this informational gap, we propose to use social network analysis based on provider information captured in registry- and EHR-based data from two neighboring healthcare institutions.

In particular, we explore the relationship between the Palo Alto Medical Foundation (PAMF) and Stanford Hospital. PAMF is a large community-based Northern California health care system whose Palo Alto Center, which provides much of the institution’s cancer care, is located directly across the street from Stanford University. Stanford Hospital is a tertiary care center that houses special expertise in cancer treatment. Patients in the area often receive care at both institutions, and many PAMF surgeons have access to operating rooms in the Stanford Hospital.

To focus our research, we chose to investigate breast cancer care across the two institutions. This area is particularly well suited to exploring patterns of care due to the commonality of multi-stage treatment, the routine involvement of multiple specialists, and the existence of nationally available, clinical-practice guidelines. Moreover, the landscape of breast cancer care as carried out in practical settings remains uncharted. The factors that determine whether efficacy in a clinical trial transfers to clinical practice are largely unknown. In many cases, treatment strategies show similar efficacy, which has propelled comparative effectiveness investigations into a major, national research priority.3,4 As in the general case, this fact holds with breast cancer therapies evaluated in randomized trials, such as mastectomy versus breast conservation and adjuvant aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen.5,6,7 Although some patterns-of-care studies have uncovered the prevalence of one treatment strategy versus others, such as the recent near-tripling of mastectomy rates in the U.S.,8 we remain ignorant of the reasons for the choices driving such trends. We believe that examining the social networks of the physicians carrying out the treatments will eventually lend insight into these larger questions.

For this study, we are interested in how patients move within and across institutions as reflected in the connections among their treating physicians. Specifically, we questioned whether patients receive all their care within a single organization. Given the proximity of PAMF and Stanford facilities, one might anticipate a steady exchange of patients, perhaps with PAMF sending more complicated cases to Stanford Hospital, which offers a distinct form of expertise. Similarly, one might expect differences in patient populations, with Stanford treating more of the complex cases. At a general level, we investigated whether patients sought out or were referred to expert, tertiary care and whether they were referred out of tertiary care into other physician networks. Put succinctly, do organizational boundaries within the healthcare system play a strong role in selecting the patient’s treating physicians?

In the next section, we describe the data and analyses, centering on the OncoShare database and the tools we used to investigate the social networks. We follow that section with a discussion of our results, where we introduce two visualizations of the physician networks and detail the qualitative and quantitative analysis of those networks. We then discuss related work that applies network analysis to other clinical data sets and other studies that investigate the referral patterns of physicians. Finally, we lay out our future research directions in the area of patterns-of-care and provide concluding remarks.

Method

Data Set

The data used in this study comes from OncoShare, a research database jointly developed by Palo Alto Medical Foundation (PAMF) and Stanford University. OncoShare supports the analyses of breast cancer care provided in academic and community health systems. The database is populated with information extracted from the electronic health records (EHRs) of Stanford University Cancer Center and multiple sites of PAMF. At Stanford, OncoShare uses the STRIDE research infrastructure,9 which contains one terabyte of data in the form of transcribed dictations, billing codes, laboratory results, and more recorded since the mid-1990s. In comparison, PAMF has detailed EHR, chemotherapy, and billing data from 2000 forward. Focusing on the overlap between Stanford and PAMF records, the database includes an initial research cohort consisting of de-identified records from all patients treated for breast cancer at Stanford and/or PAMF from 2001–2009. Development and analysis of the OncoShare database have received human subjects approval from both the Stanford and PAMF Institutional Review Boards.

In addition, OncoShare integrates data from a portion of the California Cancer Registry (CCR) maintained by the Cancer Prevention Institute of California (CPIC).10 The complete CPIC registry includes cancer incidence from 1988 onward for 2 of the 10 geographical regions delineated by CCR, recording information on cancer type, treatments received, patient survival, demographic details, and more. The total number of cases exceeds 800,000. OncoShare includes a subset of these records as defined by its research cohort, selecting for those patients treated between 2001 and 2009 whose registry information was provided by PAMF or Stanford. For this study, we used the portion of the OncoShare data derived from the CPIC subset.

Our interest in the patterns of physician interactions led us to specifically select information pertaining to the surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation therapists who cared for each patient. Since patients may have had multiple tumors or experienced recurrences, each row in the data set corresponded to a single tumor in the breast of a patient. For the purposes of examining care, we combined treatment for tumors found on the same date, connecting all the physicians from whom the patient received surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. A physician’s specialty and affiliation were key features in our analysis, and were determined in one of two ways. Using a separate file listing Stanford and PAMF physicians, including private practice surgeons operating out of the Stanford clinic, we could map the individuals to their known affiliations and specialties. Individuals outside of these organizations were assigned an affiliation of “Other” and their specialties were determined by their appearance in the PHYSICIAN_SURGEON, PHYSICIAN_MEDICAL_ONCOLOGY, or PHYSICIAN_RADIATION_ONCOLOGY fields of the OncoShare data.

Network Representation

To understand the relationships and patterns of interaction among physicians, we represented the data in terms of a social network. This formalism consists of nodes, commonly the agents who engage with each other, and edges, which represent the existence of an interaction. Additionally, the nodes and edges may have properties that further characterize the agents and their relationships. For our purposes, physicians served as nodes and their corresponding properties included type (surgeon, medical oncologist, or radiation therapist), professional affiliation (PAMF, Stanford, or Other), and the number of patients seen. We created an edge when two physicians treated the same patient for the same tumor. Notably, if a patient saw a surgeon, a medical oncologist, and a radiation therapist, we discounted the connection between the surgeon and the radiation therapist since, as shown in Fig. 1, their interaction is typically mediated through the medical oncologist. The number of patients moving between two physicians contributes to the weight of each edge.

Fig. 1.

Typical ordering of visits for a breast cancer patient receiving surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

To visualize the resulting network, we encoded the node and edge data using the Graph Modeling Language and imported the file into Cytoscape11 (version 2.8.1), a rich, extensible software environment typically used in systems biology and bioinformatics. Once we could see and interact with the structure of the network, we modified the appearance of the nodes and edges to reflect their properties and used Cytoscape’s built-in graph layout routines to help arrange the network into an organization that highlights the relationships between academic and community-based physician networks.

Network Analysis

By visualizing the network and organizing the nodes into meaningful groups, we can identify patterns of care based on the apparent connectivity among physicians. Specifically, we manually clustered the physicians by specialty and affiliation to reveal patterns of interaction within and across homogeneous groups. For instance, by viewing the number and thickness of edges between surgeons and medical oncologists, we could determine whether care frequently followed the ordering in Fig. 1 or if patients commonly received surgery and radiation without chemotherapy. We could also examine whether physicians mostly referred to others within their own organization or whether they sent patients to external locations for subsequent treatment. In general, the visual representation provides an overview of the network structure and suggests relationships that one might explore using quantitative methods.

Our central question is whether organizational boundaries within the healthcare system play a strong role in selecting the patient’s treating physicians. Therefore, we were particularly interested in the cohesiveness of subgroups of physicians in the context of the larger care network. To quantitatively assess this aspect, we employed three measures of subgroup cohesiveness from the literature on social network analysis.12 First, we look at the density of different groups of nodes, which indicates how many edges exist within a network compared to how many could potentially exist (i.e., in a complete graph). Second, we consider the strength of these networks, which is similar to density, but each edge is weighted, here by the number of patients seen by each pair of physicians. When there are a few physicians seeing most of the patients, strength can be a better indicator of within-group coherence than density. Third, we look at a direct measure of cohesiveness, which compares the density of connections within a subgroup to the number of potential edges that lead out of the group.

As another point of analysis, we also inspected the general patterns of movement across institutions. Here we focused on patients instead of physicians, examining how many patients remained within an organization versus how many were transferred to other locations for care. Under the assumption that complex cases of breast cancer may be transferred more frequently than more easily treated cases, we categorized the patients by their highest tumor stage as derived from clinical and pathological staging.

Results and Discussion

Before describing the findings based on the physician network and analyzing the various physician-level and organizational-level relationships, we provide some summary characteristics of the CPIC/CCR portion of the OncoShare database. Our selection criterion yielded 7796 patient records (3269 PAMF, 4527 Stanford) representing 6420 unique patients. Of these, 1262 patients had multiple records, which indicates that they had multiple concurrent tumors, one or more recurrences, or cancer registry entries submitted by both PAMF and Stanford. Broken down into individual procedures, we find that patients received a total of 7062 surgeries, 3583 courses of radiation treatment, and 3890 courses of chemotherapy. On average, this amounts to 2.26 treatments per record, represented by 1.10 surgeries, 0.56 courses of radiation, and 0.60 courses of chemotherapy. Overall, 94.6% of patients received surgery, 51.9% received radiation therapy, and 55.2% received chemotherapy.

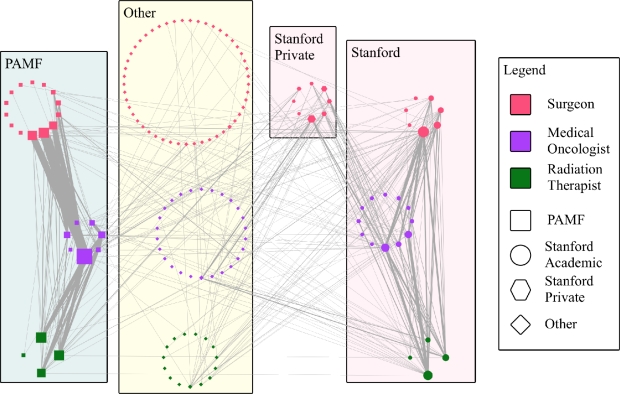

To get a broad picture of physician interactions, we first look at Fig. 2 which shows the network in its entirety. To illustrate the organizational connections, we grouped physicians by their affiliation, separating the private practice surgeons operating out of Stanford clinics from those with academic appointments. We also separated the specialties, placing surgeons at the top of the network, medical oncologists in the middle, and radiation therapists at the bottom to reflect the pattern of care illustrated in Fig. 1. As shown in the legend, the shape of each node indicates affiliation and the color indicates specialty. Additionally, the size of a node indicates the number of cases seen by the physician and the thickness of the edge indicates the number of patients shared between two physicians.

Fig. 2.

Patient mediated interactions among physicians grouped by their specialty and organizational affiliation.

This view of the social network suggests strong organizational boundaries with a plethora of weak inter-institutional connections. Specifically, we see the thickest edges appearing within the PAMF and Stanford subgroups. This finding suggests that either most patients prefer to remain in the same care network or most physicians tend to refer patients to doctors within their own organization. Importantly, we point out that neither institution implements team-centered care for breast cancer patients, which would presumably lead to even less inter-institutional communication. Furthermore, we can likely rule out insurance restrictions as a factor in lack of mobility as we know informally that most PAMF and Stanford patients subscribe to preferred provider organization plans that let them move more freely among healthcare institutions. The weak links crossing between PAMF and Stanford or from those institutions to other external physicians indicates a minor and somewhat unstructured flow of patients toward external care. Of further note, the Stanford private physicians appear to be closely tied to their academic counterparts even though one might expect them to have equally strong relationships with other physicians in private practice or with a community-based care center such as PAMF. Although these observations are interesting, with patients spread across 146 physicians and 332 edges, general patterns of interaction can be somewhat obscured. Therefore, we explored a more abstract view of the network.

Fig. 3 condenses the specialties across organizations to reduce some of the clutter in Fig. 2. Node and edge characteristics are carried over from the previous figure, with the size of the node once again indicating the number of patients treated and the thickness of an edge indicating the number of patients in common. Here the strong ties within institutions are more obvious and stand in stark contrast to the thin edges extending to other groups. With the exception of a missing edge between Stanford surgeons and PAMF radiation therapists, the PAMF and Stanford specialties form a clique, but the edge weights between the organizations range from 1 to 11 with an average of 6.1 shared patients assuming a complete subgraph. In contrast, Stanford does not form a clique with the Other group, with edge weights ranging from 3 to 44, again assuming a complete subgraph, the average number of shared patients is 11.7.

Fig. 3.

Patient mediated interactions among physician specialties within and across organizational boundaries.

In the context of these facts, we should reiterate the point that Stanford Hospital, quite literally, sits across the street from the PAMF Palo Alto Center where 3 of its 4 radiation oncologists and 4 of its 7 medical oncologists operate. Although even this small distance could limit interactions among physicians, the distance is unlikely to be a primary factor for the lack of patients seen at both institutions. Even local patients routinely travel a few miles to receive care at either institution and other patients are known to have traveled across the country and even internationally for treatment at Stanford Hospital. This fact makes it all the more surprising that few patients move across institutions. Finally, we briefly mention that the ties between Stanford private surgeons are clearly stronger with Stanford oncologists than others and that, even in this case, the connections to external, non-PAMF physicians appear stronger than with doctors working at PAMF.

To complement the network visualizations, we calculated density, strength, and cohesiveness measures of nodes that appeared to comprise coherent subgroups based on the figures. Tab. 1 collects the results, which were computed over the network in Fig. 2. The subgroups included PAMF, Stanford, a combination of the PAMF and Stanford nodes loosely supported by the clique in Fig. 3, and for comparison, groups formed by combining each of PAMF and Stanford with all nodes in the Other category. Density and strength were calculated using only those edges that connect nodes within the same group, whereas cohesion incorporates the edges leading out of the group. Since the categorization of the Stanford private surgeons is somewhat unclear, we provide one set of numbers where we consider them as separate from Stanford academic physicians and another set (e.g., Density+SP) where we consider them as part of the Stanford subgroup.

Tab. 1.

The measures report a subgroup’s internal (density, strength) and external (cohesion) connectivity. Scores were calculated treating Stanford private surgeons as operating outside the Stanford network and by folding them into the Stanford group (+SP).

| Subgroup | Density | Strength | Cohesion | Density+SP | Strength+SP | Cohesion+SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAMF | 0.10 | 2.36 | 3.83 | 0.10 | 2.36 | 3.83 |

| Stanford | 0.14 | 1.18 | 3.13 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 3.11 |

| PAMF + Stanford | 0.07 | 0.92 | 2.71 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 3.35 |

| PAMF + Other | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.21 |

| Stanford + Other | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.51 |

When attempting to assess the coherence of each subgroup, the first point that we notice is that in all cases, density is low. The overall graph density is 0.02, and the various groups range from 0.01 to 0.14. As Friedkin13 points out, such small density values can be misleading as a measure of structural cohesion and that density itself can be difficult to compare across networks when they vary in size. Regardless, we think it is safe to conclude that on average, physicians have small networks compared to their total potential interactions even within their own organizations.

Since the graph edges are weighted by the number of interactions, we can get a clearer sense of within-group activity by looking at the strength of various subgroups. These results show that interactions between physicians are on average stronger within PAMF than within any of the other groups. Moreover, extending the network to include any other suspected subgroup substantially reduces the strength, which means that the new connections tend to be much weaker than those within PAMF. Additionally, we find that incorporating the private surgeons into the Stanford category reduces the strength of the affected subgroups.

Subgroup cohesion lets us determine whether ties are more prevalent among members within a subgroup than between those members and outside physicians. When cohesion equals one, there is no difference in prevalence, calling into question the existence of the subgroup. A cohesion greater than one indicates that the ties to nodes within the group are more common than to nodes outside the group. The numbers in Tab. 1 show that Stanford and PAMF are a clear subgroup. Furthermore, when contrasted with connections to physicians in the Other category, the combined group of Stanford and PAMF is a meaningful construct. Recall that we drew the same conclusion from Fig. 3, where we also pointed out the relative paucity of patients moving across the connecting edges. Interestingly, cohesion increases in most relevant subgroups when Stanford academic and private practice are combined. We hesitate to draw conclusions from this, but this may indicate that the Stanford private group provides a valuable link between Stanford academic physicians and those from other institutions.

The reported findings led us to wonder whether there was a relationship between the complexity of a patient’s cancer and the likelihood that they would be transferred in to or out of an organization such as PAMF or Stanford Hospital. Although age of diagnosis also factors into cancer complexity, we rely solely on the derived tumor stage to make this distinction. Tab. 2 presents the results, dividing them into patients who initially received surgery at either PAMF or Stanford (academic physicians only) and subdividing these into patients who stayed within their initial care group and those who transferred to another source of care.

Tab. 2.

Patients receiving surgery at PAMF or Stanford and either staying within the organization or moving outside.

| From | PAMF | Stanford | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To | PAMF | All Others | Stanford | All Others | ||||

| Stage | Patients | % All Patients | Patients | % of Stage | Patients | % All Patients | Patients | % of Stage |

| 0 | 365 | 26.37% | 3 | 0.82% | 448 | 26.48% | 25 | 5.29% |

| 1 | 521 | 37.64% | 7 | 1.33% | 525 | 31.03% | 65 | 11.02% |

| 2 | 392 | 28.32% | 8 | 2.00% | 427 | 25.24% | 54 | 11.23% |

| 3 | 69 | 4.99% | 6 | 8.00% | 120 | 7.09% | 12 | 9.09% |

| 4 | 13 | 0.94% | 0 | 0.00% | 14 | 0.83% | 2 | 12.50% |

For each condition, we looked at four different numbers subcategorized by tumor stage. First, we report the number of patients in each category to get a sense of their magnitudes. These values show that PAMF and Stanford see similar but significantly different (p=0.02: two-tailed, paired t-test) numbers of patients at each stage of cancer, with Stanford surgeons treating more patients even though PAMF has greater manpower. Moreover, Stanford sees substantially more women with Stage 3 breast cancer. Second, when patients remained within a group, we looked at the percent of patients diagnosed at each stage to get an idea of the distribution of case complexity across institutions. There is some evidence that PAMF treats proportionately more patients in Stages 1 and 2 than Stanford, but the differences are not statistically significant. Third, we record the number of patients who transfer out of their original organization, assuming surgery as the first treatment. Here we can clearly see that patients tend to stay within the PAMF network in contrast to their treatment at Stanford. Fourth, we look at the percentage of patients in each stage who leave PAMF or Stanford after surgery. The distribution of these percentages also differ significantly (p=0.02: two-tailed, paired t-test) as we see that several patients seek care outside of Stanford after surgery and that women with Stage 3 breast cancer are more likely to seek care outside of PAMF than those with other stages of the disease. Still, the raw numbers here are quite small and continue to reflect a general lack of inter-institutional interaction.

Related Work

Mathematical and computational approaches for network analysis have existed for decades, but applications in clinical domains are a recent phenomenon. For instance, Iwashyna et al.14 examined the organizational structure of hospital patient-transfer networks and found that those hospitals that could deliver more services were more centrally located in the informal networks. More recently, these researchers found that patients are routinely involved in transfer cascades where they are sent to locations other than the hospital’s primary referral site.15 In other work, Bhavnani et al.16 used network analysis to investigate the relationships among comparative effectiveness studies to better understand the landscape of evidence in depression trials. In the area of physician interactions, studies have emphasized team interactions within small groups17 and communication patterns among physicians within a hospital.18 Notably none of these studies has investigated the relationships based on patterns of care within and across institutions.

Nonetheless, some researchers have looked at the patterns of physician referrals, which are closely related to the interactions described in our investigation. Shortell19 offers perhaps the earliest such study, where he looked at referral networks in the context of each physician’s professional status. On a much larger scale, Shea et al.20 analyzed a survey of Medicare beneficiaries to determine the number of referrals, the sources of referrals, and related factors. Following this direction, Kinchen et al.21 surveyed hundreds of primary care doctors to uncover the important considerations that influence specialist referrals. With a few exceptions (e.g., Shortell’s work), research on referral patterns has not used the methods available from network analysis and have not explicitly examined the relationship between two neighboring healthcare organizations.

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

Expanding on this study, our future research will incorporate additional physician and patient related information. Importantly, as we continue to populate OncoShare, our analyses will grow to include more detailed information on treatment histories and physician interactions. Moving in one direction, we intend to further characterize individual physicians by the types of cases they see and the treatments that they carry out. In a second direction, we are currently investigating patterns of patient care (e.g., what procedures did they receive and under what conditions), which we plan to tie to patterns of physician referrals. This level of detail should let us compare the variety of care received across healthcare organizations, an important area of research given the current study’s finding of strong institutional boundaries.

We also intend to model the movement of patients through the physician network. Initially, we plan to compare the static model of the physician network to one where patients move randomly among the physicians according to a model of care based on Fig. 1. We also expect to build predictive models of a patient’s pattern of care and apply them to answer questions such as, “Under what conditions might a patient seek care outside of their initial healthcare institution.” In general, we think that the application of techniques from social network analysis opens the door to detailed studies of the healthcare system that have previously been out of reach.

We also need to collect data related to the patient’s care and their sense of choice and involvement while seeking treatment. While carrying out this study, we lacked reliable information about a patient’s primary care physician (PCP) and as a consequence, limited our investigations to interactions among specialists. However, the PCP, who interacts with a large network of specialists,22 may play a strong role in determining the particular physicians that a patient sees and may exhibit a nontrivial influence on a patient’s decision to stay within an organization. In a similar vein, we have assumed that a patient’s preferences are strong enough to override the inertia imposed by institutional boundaries. This premise may not hold, and further research needs to investigate the personal dynamics involved.

Throughout the paper we have used the word “interaction” when we really wanted to say “referral.” Unfortunately, we still lack the information that would support a model of the typical referral process in breast cancer care. With this caveat, we claim that these interaction patterns are closely related to physician referral patterns and that they offer a clear view of the supporting social structures. Questions that we cannot answer at this point are those pertaining to the agents who drive the movement of patients through this network. Who determines a patient’s treatment course—whether one or more physicians, the patient herself, or a combination of factors—remains to be addressed, but we have moved closer to a model.

To summarize, we have investigated the patterns of care in two neighboring healthcare facilities, each of which plays a different role in the healthcare system. Even though the findings may confirm existing intuitions, this study offers a novel, principled, and scientific analysis that provides a foundation for future research in this area. Specifically, we have found that strong intra-organizational ties exist among physicians overseeing breast cancer treatments, and that patients are likely to stay within the environment where they first receive treatment. Also, each institution has weak ties to the other and to a group of external physicians, although we have not considered the directionality of these links to explore whether patients transfer from or to these outside sources. Further, we have found that patient populations at Stanford and PAMF differ in terms of their tumor stage, which roughly indicates the complexity of each case. In addition, we saw that after their initial surgery patients are more likely to transfer out of Stanford than out of PAMF. Overall, we have shown that organizational boundaries within the healthcare system play a strong role in selecting the patient’s treating physicians.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the Susan and Richard Levy Gift Fund and by NIH Grant R01LM09607-01. We thank the following people for discussions that contributed to this research: Allison Kurian, Wei-Nchih Lee, Harold Luft, Cliff Olson, Tina Seto, and Susan Weber. We also extend our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

References

- 1.Kahn KL. On referral patterns for patients with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;3:244–246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz SJ, Hofer TP, Hawley S, et al. Patterns and correlates of patient referral to surgeons for treatment of breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:271–276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iglehart JK. Prioritizing comparative-effectiveness research—IOM recommendations. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:325–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sox HC, Greenfield S. Comparative effectiveness research: a report from the Institute of Medicine. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151:203–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baum M, Buzdar A, Cuzick J, et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination) trial efficacy and safety update analyses. Cancer. 2003;98:1802–1810. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:1233–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:1227–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuttle TM, Habermann EB, Grund EH, Morris TJ, Virnig BA. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:5203–5209. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe HJ, Ferris TA, Hernandez PM, Weber SC. STRIDE—an integrated standards-based translational research informatics platform. Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium; 2009. pp. 391–395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Prevention Institute of California Registry operations. http://www.cpic.org; accessed March, 2011.

- 11.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasserman S, Faust K. Social network analysis: methods and applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedkin NE. The development of structure in random networks: an analysis of the effects of increasing network density on five measures of structure. Social Networks. 1981;3:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, Moody J, Kahn JM, Asch DA. The structure of critical care transfer networks. Medical Care. 2009;47:787–793. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318197b1f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unnikrishnan KP, Patnaik D, Iwashyna TJ. Spatio-temporal structure of US critical care transfer network. Proceedings of the AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science; 2011. pp. 74–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhavnani SK, Carini S, Ross J, Sim I. Network analysis of clinical trials on depression: implications for comparative effectiveness research. Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium; 2010. pp. 51–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lurie S, Fogg T, Dozier A. Social network analysis as a method of assessing medical-center culture; three case studies. Academic Medicine. 2009;84:1029–1035. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ad16d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Marsden PV. Factors affecting influential discussions among physicians: a social network analysis of a primary care practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:794–798. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shortell SM. Patterns of referral among internists in private practice: a social exchange model. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1973;14:335–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shea D, Stuart B, Vasey J, Nag S. Medicare physician referral patterns. Health Services Research. 1999;34:331–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Levine D, Wang NY, Powe NR. Referral of patients to specialists: factors affecting choice of specialist by primary care physicians. Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2:245–252. doi: 10.1370/afm.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham HH, O’Malley AS, Bach PB, Saiontz-Martinez C, Schrag D. Primary care physicians’ links to other physicians through Medicare patients: the scope of care coordination. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150:236–242. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]