Abstract

When patients share personal health information with family and friends, their social networks become better equipped to help them through serious health situations. Thus, patients need tools that enable granular control over what personal health information is shared and with whom within social networks. Yet, we know little about how well such tools support patients’ complex sharing needs. We report on a lab study in which we examined the transparency of sharing interfaces that display an overview and details of information sharing with network connections in an internet-based personal health information management tool called HealthWeaver. Although participants found the interfaces easy to use and were highly confident in their interpretation of the sharing controls, several participants made errors in determining what information was shared with whom. Our findings point to the critical importance of future work that examines design of usable interfaces that offer transparent granularity in support of patients’ complex information sharing practices.

Introduction

When patients share personal health information with family and friends, they create informed social networks that are prepared to actively assist them in managing serious illness. For example, family and friends become equipped to help cancer patients with rides to the treatment center, family care, household chores, or even assist in seeking out treatment information when they are kept up to date about the patient’s status.1 However, patients do not share their health information equally with all members of their social network. For example, some patients share their cancer diagnosis with many people, but share details about their treatment recovery with only a few people. Although social networks are most effective when kept up to date, patients often lack the time and energy required to manage complex sharing of information from medical records, reflections, appointments, and other personal resources.

Because patients with serious illness, such as cancer, share a range of personal health information with many people as their health situation evolves,2 the design of technology that can support the complex communication and support needs of such patients is critical.3 Yet, individuals have serious concerns about the privacy of personal information in online tools, such as personal health records (PHR).4–6 When people share health information in online communities, both general purpose and health-specific, they take great effort to build and maintain networks with which they interact.7 Rather than defining a hard boundary between what information is shared and what information remains private, patients’ sharing reflects a fluid negotiation as the type and amount of information shared with select family and friends changes over time.2 However, access policies for granular sharing of sensitive health need to be carefully defined to preserve privacy and confidentiality.8

As more of our personal information goes online, patients need tools that enable granular control over sharing personal health information without introducing the potential for privacy risks due to unintentional disclosure.8 Specifically, patients should have the ability to specify exactly what information is shared with an individual. Although such granular sharing controls have been examined in other settings, we know little about how well patients can use these controls to meet their complex sharing needs. In the work we present, we examined the transparency of sharing interfaces that enable granular control over sharing personal health information with selected members of people’s social networks. Before describing that work, we discuss related work to illustrate the research gaps that the contributions of our work fill.

Related Work

Technology designed to support the widespread dissemination of health information within a social network has largely arisen through grassroots efforts, such as CarePages.com and CaringBridge.org. These web-based tools provide places for patients both to inform their social networks, by posting messages or other content, and to receive messages of support. Although patients need transparent and easy to use interfaces that enable them to manage complex sharing practices, little research has investigated how well online tools support patients’ needs for granular control over health information sharing. Weitzman et al,6 through a study of user acceptability of the Indivo personally-controlled health record, found that sharing capabilities were highly valued by users, but these access control for sharing health records were underutilized by users in favor of workarounds, such as sharing passwords with family members. In other work, Caine et al.,9 designed a privacy management interface that enables older adults to easily turn on or off the distribution of home monitoring data to distant caregivers through a simple ‘switch’ metaphor. Although this metaphor may work well for a small network of the patients and 1–2 caregivers, it may not scale to the larger, more diverse social networks with whom cancer patients share many types of data.

Outside the health context, much research has examined formal access controls lists (ACL) that specify which users can access digital content in a variety of settings, such as professional organizations10 or the home.11 ACLs tend to be quite expressive, often making access policies complicated to set up and cumbersome to modify over time.12 The regularity with which users, including well-trained system administrators, make mistakes setting up ACLs is troubling, indicating that better interfaces for these controls are necessary, even for experienced users.10,13 Recent privacy research has called into question the use of extensive ACLs that must be kept up to date. For example, Dourish et al.12 argue instead, for embedding privacy controls into interfaces where content is being acted on (e.g. shared, created, or viewed) such that privacy decisions can be made in context and will be readily visible to users.

Although traditional ACLs are a common means for supporting information sharing, the complexities of cancer patients’ sharing needs illustrate critical limitations. First, exactly what and with whom patients share often changes over time,2,8 which requires continuous updating of ACLs. Second, the tremendous stress and treatment effects, such as “chemobrain”,14 that cancer patients can experience indicate a need for simple, easy to use sharing features. Third, the implications of unintentional sharing, or ‘misclosure’,9 of sensitive health information can be devastating. The rigidity and problematic usability of traditional ACLs require an alternative approach to support patients’ needs. Patients need to feel assured, through transparent and easy to use controls, that information technology is sharing their private health information as they expect it to, regardless of the complexity of their sharing needs.

Social networking tools, such as Facebook (www.facebook.com) and Google+ (plus.google.com) have begun to support fluid access controls, integrating them throughout their interfaces. For example, when creating a new piece of information (e.g., a photo or a wall post), Facebook users can specify, in context, whether they want to share it with “everyone,” “friends of friends,” “friends only,” or a customized set of friends from their network. Following this model of granular control, Lipford et al.15 explored visual interfaces that help users create and modify privacy settings in Facebook, including a visual matrix that illustrates who has access to which specific personal information the user maintains (e.g., contact information, education information). While many have concerns about sharing health information through general-purpose tools like Facebook,7 some third party PHRs, such as HealthVault,16 provide similar support for granular sharing. Unfortunately, the dearth of studies in which such sharing interfaces have been evaluated in health settings leaves us wondering how transparent these kinds of interfaces are for patients who want granular control for sharing their sensitive personal health information. Given these trends in granular sharing support in social computing, we investigated the transparency of sharing interfaces designed for use in context, providing both quick overviews of sharing status with visual icons and detailed views of sharing with lists.

Study Context

Our goal in this study was to identify interfaces that make granular sharing of personal health information easy for patients to understand and use. In other words, we aimed to determine which sharing interfaces were most transparent. Transparency refers to the ease of understanding the state of a system through its interface.17,18 Having transparency allows users to remain in the flow of their work without disruption and provides visibility about system behavior that is required by users to understand the security of their information.19 In the context of an information management tool called HealthWeaver, we conducted a lab study to compare the transparency of interfaces that provide patients with granular control over sharing personal health information with their social networks. For the purpose of this study, a transparent interface is one that makes clear how the user’s personal health information is shared with their network connections within HealthWeaver. Before detailing the sharing interfaces we assessed and our study procedures, we describe the HealthWeaver system.

HealthWeaver is a web-based tool we designed to support the information management needs of cancer patients. HealthWeaver enables patients to create, manage, and share personal health information with selected members of their social networks, known as network connections. In addition to features for tracking health and wellbeing20 and requesting help from one’s social network,1 patients can upload documents, create notes, lists, blog posts, web bookmarks, and calendar events, and then share any of these HealthWeaver objects with their network connections. This object-level approach to sharing is complex, but facilitates the granular control patients need.

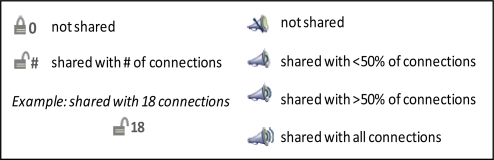

To investigate the design of granular sharing controls, we created two sets of alternative sharing interfaces. The first set provides a glanceable overview of the subset of network connections with whom an individual HealthWeaver object is shared (Figure 1). We designed simple privacy icons to help the user determine, at a glance, if information is shared and with roughly how many people. The goal of the icons is to enable users to quickly verify that objects are being shared as intended and to make unintentional sharing easily discoverable. Using the icons, users need to be able to (1) determine if their information is shared, and (2) have a rough sense of how many people can see the information. Displaying the first attribute (i.e., shared or not) could be done in a binary fashion, but the second required either an exact number or a proportional representation. We selected the megaphone icon (Figure 1, right) to display the proportional representation (e.g., shared with no one, some portion of the network, or everyone). As an alternative, we paired the binary lock icon (Figure 1, left) with an exact number. We anticipated that the megaphone would be easier for users to grasp than requiring them to perform mental calculations with exact numbers using the lock. In the lab study, we examined how well each alternative privacy icon provided a transparent overview of information shared in HealthWeaver. The HealthWeaver object was labeled with one of these 2 privacy icons, depending upon the study condition.

Figure 1.

Privacy Icons. The lock icon (left) indicates whether the object is “shared” (i.e., open lock) or “not shared” (i.e., closed lock) accompanied by the number of network connections with whom the object is shared. The megaphone icon (right) provides a pictorial representation of the proportion of network connections with whom the object is shared using waved lines.

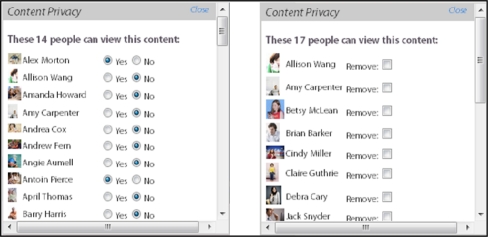

We designed a second set of sharing interfaces to present the details of the specific network connections with whom a particular HealthWeaver object is shared. Figure 2 shows the complete sharing list (left) and the selected sharing list (right). The sharing lists were presented when the user hovers over a privacy icon. Both lists are interactive, enabling the user to add or remove connections for a given object. During the design process we identified many ways to display exactly who can see a shared object, however these options boiled down to two underlying representations: displaying the access level for everyone (i.e., complete sharing list) or displaying the access level of only the subset with access (i.e., selected sharing list). We created simple interfaces for each representation to assess their transparency and ease of use. Similar types of sharing controls have been used to communicate sharing settings in other tools that support sharing in social networks, such as Facebook. In the lab study, we examined how well each alternative sharing list provided transparent and easy to use details about information sharing. Our expectation was that findings would indicate which type of sharing interface from each set (i.e., privacy icons and sharing lists) was most transparent. Those interfaces could then be implemented as a pair that works together to enable granular sharing.

Figure 2.

Sharing Lists. The complete sharing list (left) shows all the user’s network connections with a radio button beside each to indicate whether the object is shared (i.e., Yes) or not shared (i.e., No). The selected sharing list (right) shows only those network connections with whom the object is shared. The user can mark the checkbox beside a connection to remove that person from the list.

Methods

We conducted a lab study with 20 cancer patients and survivors to compare the transparency among the alternative sharing interfaces. The study received IRB approval through the University of Washington. We recruited a convenience sample of participants through flyers. After providing written informed consent, each participant took part in a single session lasting 60 minutes. The session was comprised of 3 parts. During part 1, participants described their own health information sharing practices during cancer care, including the number and types of people with whom they shared. After introducing HealthWeaver, we asked participants to assume a fictitious persona named ‘Terry’ during parts 2 and 3 of the session as they completed tightly scripted tasks and answered questions about sharing information within HealthWeaver. We explained that Terry is a cancer patient who is using HealthWeaver to share information with 74 family members and friends. Each participant was given a paper list with the names and profile pictures of the network connections in Terry’s HealthWeaver account. Each participant used a copy of this account for systematic comparisons of the sharing interfaces in parts 2 and 3 of the session. The account was pre-seeded with fictitious HealthWeaver objects, including notes, blog posts, and calendar appointments that were shared with a pre-set portion of Terry’s network connections. In part 2 of the session, participants compared the transparency of the alternative privacy icons. During part 3, participants compared the transparency and ease of use of the alternative sharing lists. Participants were not told the meaning of either type of icon and received no training on how to use the sharing features.

Part 1: Assessing Health Information Sharing Practices

To understand the participants’ orientation towards sharing personal health information with their social networks during cancer care, we began the session by asking the participants to answer the following three questions: (1) “Approximately how many people, not counting your doctors and nurses, have you talked to about your cancer diagnosis?”, (2) “Approximately how many people, not counting your doctors and nurses, have you talked to about the treatments you’ve had for cancer?”, and (3) “Have you ever talked about the cancer treatment process with people who fall into these categories? (check all that apply: close family, friends, distant family, neighbor, colleague, manager, another cancer patient, acquaintance, other)”. We calculated the mean number of people with whom participants shared and counted the number of participants who shared with each type of person.

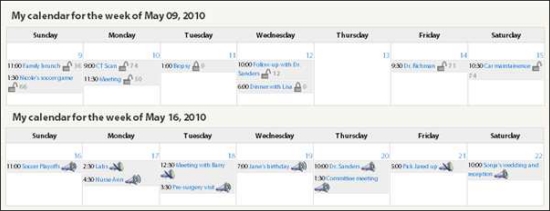

Part 2: Comparing alternative privacy icons to overview sharing

To compare the transparency of the privacy icons, we embedded them onto individual events on the weekly view of Terry’s calendar in HealthWeaver (Figure 3). We chose the calendar for placement because it is the most space-limited interface in HealthWeaver. Each participant completed 8 trials in total: 4 trials for the lock condition and 4 trials for the megaphone condition. Each trial presented a version of the interface in which calendar events were shared with different connections in Terry’s network. The order in which trials were presented to participants was randomized across the 8 trials to minimize order effects. On each trial, the participant answered the following questions to assess transparency: Given a specific calendar event (e.g. “For the follow-up appointment with Dr. Sanders on May 12”), (T1) Is this appointment shared with anyone? (i.e., yes/no), and (T2) Approximately how many people from your network can see this appointment? (i.e., less than half my network, more than half of my network, or everyone in my network). After answering each transparency question, we asked participants to report their level of confidence in their answer on a 4-point scale (i.e., 1=‘Guess’, 2=‘A little confident’, 3=‘Fairly confident’, 4=‘Completely confident’). When the participants completed all 8 trials, we assessed their interface preference by asking them to report which icon display they liked best.

Figure 3.

Lock icons (top) and megaphone icons (bottom) embedded on appointments within the weekly calendar

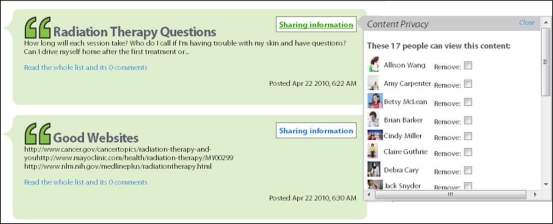

Part 3: Comparing alterative lists to detail sharing

To compare the transparency of the complete and selected sharing lists, we embedded each sharing list on posts created by ‘Terry’ in HealthWeaver (Figure 4). Terry can control who can see an individual post through radio buttons on the complete sharing list or through check boxes on the selected sharing list. Each participant completed 4 trials in total: 2 trials for the complete sharing list condition and 2 trials for the selected sharing list condition. Each trial presented a version of the interface in which posts were shared with different people in Terry’s network. The order in which trials were presented to participants was counterbalanced. On each trial, the participant answered the following questions to assess transparency: (T1) Is this information shared with anyone? (yes/no), and (T3a) Can [person x] see this object?, where ‘person x’ is a network connection (e.g., ‘Debra Cary’) with whom the post is shared, and the opposite case (T3b) Can [person y] see this object?, where the post is not shared with ‘person y’.

Figure 4.

Selected sharing list hovers over a post when the ‘sharing information’ link is clicked. This link is intended to be replaced with the most transparent privacy icon

After answering each transparency question, we asked participants to report their level of confidence on the 4-point scale. Next, we measured the ease of use21 of each sharing lists by determining whether the participant could correctly modify sharing permissions of posts. For each sharing list, we asked the participant to (E1) Make it so that person x (e.g., Cindy Miller) can see this post, and (E2) Make it so that person y can no longer see this post. When the participant completed the two ease of use tasks for each sharing list, we assessed their interface preference by asking them which sharing list they liked best.

Data analysis

We assessed the transparency of each sharing interface by scoring the accuracy of participants’ answers to the transparency questions, T1 and T2 for the privacy icons, and T1, T3a, and T3b for the sharing lists. Answers to each question were scored as correct or incorrect. We first calculated the error rate for each condition by counting the total number of errors participants made over all 80 trials for each icon display (i.e., 4 trials per participant per condition) and over all 40 trials for each sharing list (i.e., 2 trials per participant per condition) for T1, T2, T3a and T3b. Because we found a significant difference between the total errors on T3a and T3b with McNemar’s Chi square tests (X2 =35.2, p<0.001), we analyzed T3a and T3b separately. To account for repeated measures, we next calculated participant errors as the total number of errors each participant made on all trials they completed for each condition. We calculated the average participant error for each condition and used the Wilcoxon signed rank test (V) to compare the distribution of participant errors between conditions.

We assessed ease of use of each sharing list by scoring the accuracy of participants’ ease of use tasks, E1 and E2, as correct or incorrect. We calculated the error rate for each list by counting the total number of errors participants made over all 40 trials (i.e., 2 trials per participant per condition). Because we found no difference between E1 and E2 with McNemar’s Chi square tests (X2=1.33, p=0.25), we took the total number of errors each participant made across E1 and E2 as the participant error on ease of use tasks (E) for each condition. We used this total to calculate average participant errors for each condition. We used the Wilcoxon signed rank test (V) to compare the distribution of participant errors between lists.

We assessed confidence on transparency questions and on ease of use tasks by calculating each participant’s average rating (i.e., 1–4) across trials for each T1, T2, T3a, T3b, T3, and E. Because ratings were ordinal Likert scale data, we compared the distribution of median ratings between conditions with Wilcoxon signed rank tests (V).

We assessed interface preference by counting the number of participants who reported a preference for each sharing interface. We then compared frequency counts between conditions using Chi square tests (X2).

Finally, we examined participant errors in relation to their reported level of confidence. For participants who made errors, we used Wilcoxon signed rank tests (V) to compare the confidence level they reported on trials in which they made errors to the confidence level they reported on trials in which they made no errors. We used the median confidence in this comparison when participants made errors on more than one trial per condition. We used ‘R’ statistics package (http://www.r-project.org/) to compute all statistical tests in our data analysis.

Results

Of the 20 cancer patients and survivors who took part in this study, 14 had been diagnosed with breast cancer and the remaining participants had been diagnosed with prostate (2/20), thyroid, colon, squamous cell carcinoma, and uterine cancer. Participants ranged in age from 33 to 64 years (mean = 51 years), were predominately female (17/20), and most had either a college degree (8/20) or graduate degree (7/20). Participants were regular computer users, all reporting computer use on most days and having learned to use a computer 4–10 years ago (3/20) or longer (17/20). Half of participants (10/20) reported daily use of social networking software (e.g. Facebook or LinkedIn); the other half used such tools infrequently (5/20) or not at all (5/20). Seven participants had used a website specifically developed for sharing health information with one’s social network (e.g., CarePages.org).

Health Information Sharing Practices

Participants reported sharing health information with a wide range of people from their social networks. The number of social connections—not including health professionals—with whom participants shared information about their cancer diagnosis and treatments varied from 10 people to several hundred people. On average, participants reported sharing diagnosis information with 75 people from their social networks. Although 8 participants reported sharing treatment information with fewer people than diagnosis information, participants reported sharing treatment information with an average of 97 people from their social networks. Table 1 shows the percentage of participants who shared information with each type of person. Four participants reported additional types of people with whom they shared, including business associates, online friends, strangers at retreats, and teachers.

Table 1.

Percentage of participants who shared with each type of social connection

| Type of social connection | % of participants |

|---|---|

| Close family | 100% |

| Friend | 100% |

| Another cancer patient | 90% |

| Colleague | 75% |

| Neighbor | 75% |

| Acquaintance | 55% |

| Manager | 55% |

| Distant family | 50% |

Information sharing overview: Lock versus Megaphone privacy icons

Although participants were highly confident in their interpretation of both privacy icons, several participants made errors in determining what was shared with whom, particularly with the megaphone icon. Table 2 compares error rate, participant errors, confidence levels, and participants’ preferences for the lock icon and megaphone icon. The data demonstrate that the lock was significantly more transparent to participants than the megaphone for transparency question T2 (V=3.5, p<0.01). Alarmingly, errors were made on 40% of megaphone trials and made by 80% of participants. Further, participants were significantly more confident when judging how information is shared using the lock for both transparency question T1 (V=59.5, p<0.05) and T2 (V=61.0, p<0.05). Finally, participants unanimously preferred the lock (X2=20.0, p<0.001). Participants agreed that the lock was much simpler and easier to readily understand than the megaphone. In particular, they found the numbers beside the lock clear and felt they took less time to process than figuring out the subtle lines of the megaphone’s pictorial metaphor. One participant explained, “with an intense situation like cancer, it is important that things be readily understandable.” One participant confused the megaphone for an audio clip. Another participant thought the megaphone signaled an alarm.

Table 2.

Comparison of lock and megaphone

| Measure | Lock | Megaphone | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Error rate | 2.5% (2/80) | 11.3% (9/80) | |

| Is it shared? | Participant errors median (range), mean (sd) | 0 (0–1), 0.10 (0.31) | 0 (0–3), 0.45 (0.89) | V = 5.0, p = 0.143 |

| Participant confidence median (range), mean (sd) | 4 (1–4), 3.33 (0.83) | 3 (1–4), 2.61 (0.95) | V = 59.5, p = 0.020* | |

| T2 | Error rate | 8.8% (7/80) | 40% (32/80) | |

| How many people can see it? | Participant errors median (range), mean (sd) | 0 (0–2), 0.35 (0.67) | 2 (0–3), 1.60 (0.99) | V = 3.5, p = 0.001** |

| Participant confidence median (range), mean (sd) | 4 (1–4), 3.23 (0.97) | 3 (1–4), 2.39 (1.00) | V = 61.0, p = 0.012* | |

| Preference | Participant count | 20/20 | 0/20 | X2 = 20.0, p<0.0001*** |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

We next explored the errors made by participants. For transparency question T1 (Is it shared?) on the lock display, only 2 errors were made in total. One error was made by each of 2 participants. In contrast, 5 different participants made a total of 9 errors on the megaphone display. Of those 5 participants, 2 participants made 1 error each, 2 participants made 2 errors each, and the remaining participant made 3 errors. For transparency question T2 (Approximately how many people can see it?), 5 participants made a total of 7 errors on the lock display. Of those 5 participants, 3 participants made 1 error each and the remaining 2 participants made 2 errors each. In contrast, all but 4 participants made at least one error on the megaphone display. Of the 32 errors made in total, 3 participants made 1 error each, 10 participants made 2 errors each, and 3 participants made 3 errors each. One participant who made 3 errors did not report their level of confidence and was excluded from the following analysis.

We then compared the confidence level reported by participants on trials in which they made errors to trials in which they did not make errors. We expected that participants would report lower confidence when they made errors. Table 3 compares participants’ confidence levels for trials with and without errors on transparency question T1 for both the lock condition and the megaphone condition. For the lock, participants’ confidence was identical. In contrast, participants who made errors on the megaphone reported lower confidence when they made errors than when they did not make errors (p=0.098). For example, one participant who made errors with the megaphone rated the confidence in her answers as a ‘1’ on the 4-point scale and told us “I am guessing here and you don’t want to guess with sharing medical information”.

Table 3.

Comparison of confidence on trials in which participants made errors and did not make errors on transparency question T1: “Is it shared?”

| Lock | Megaphone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant number | Number of errors | Confidence on trials with errors | Confidence on trials without errors | Participant number | Number of errors | Confidence on trials with errors | Confidence on trials without errors |

| P5 | 1 | 3 | 3 | P3 | 2 | 2.5 | 4 |

| P15 | 1 | 3 | 3 | P8 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| P11 | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| P13 | 1 | 1 | 1.3 | ||||

| P16 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||

Next, we compared participants’ confidence on trials in which they made errors on transparency question T2 and trials when they made no errors on T2 (Table 4). Data for participants who failed to report confidence on a trial (i.e., n/s for not specified) were excluded from this analysis. Compared to transparency question T1, in which we observed a drop in confidence when participants made errors on the megaphone, there was no difference in confidence when participants made errors on T2 for either the lock (V=1.0, p=1.0) or megaphone (V=5.5, p=0.679).

Table 4.

Comparison of confidence on trials in which participants made errors and did not make errors on transparency question T2: “How many people can see it?”

| Lock | Megaphone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant number | Number of errors | Confidence on trials with errors | Confidence on trials without errors | Participant number | Number of errors | Confidence on trials with errors | Confidence on trials without errors |

| P1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | P1 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| P5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | P2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| P12 | 2 | 2 | 1 | P3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| P15 | 1 | n/s | 1 | P4 | 3 | n/s | n/s |

| P19 | 1 | 3 | 3 | P5 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| P6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| P8 | 3 | 2 | n/s | ||||

| P9 | 1 | 2 | 1.5 | ||||

| P10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| P11 | 2 | n/s | 3 | ||||

| P12 | 2 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| P13 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| P15 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| P16 | 1 | n/s | 4 | ||||

| P17 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| P20 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | ||||

Information sharing detail: Complete versus Selected sharing lists

We now turn to our comparison of transparency and ease of use of the alternative sharing lists. Although participants were highly confident in their interpretation and use of both sharing lists, several participants made errors in determining what was shared with whom and in using the lists to modify sharing settings. Table 5 compares error rates, participant errors, confidence levels, and participants’ preferences for the complete sharing list and the selected sharing list. The data demonstrate no significant difference in transparency or ease of use between the lists. Although participants made fewer errors on the selected sharing list, there was no significant difference in participant errors between the two lists for T1, T3a, T3b, or E. Similarly, there was no difference between the two lists in the level of confidence reported by participants for T1, T3a, T3b, or E. However, there was a significant preference for the complete list over the selected list (X2 =5.0, p<0.025). Participants who preferred the complete sharing list explained that they liked seeing the entire network and the sharing status of each person, which helped them feel certain that information was not shared with people whom they did not want having access. One participant wanted every person listed to prevent forgetting to share with someone. A participant who preferred the selected sharing list explained that she liked dealing with a shorter list of people.

Table 5.

Comparison of complete and selected sharing lists

| Measure | Complete list | Selected list | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Error rate | 12.5% (5/40) | 7.5% (3/40) | |

| Is it shared? | Participant errors median (range), mean (sd) | 0 (0–2), 0.25 (0.55) | 0 (0–1), 0.15 (0.37) | V = 10.0, p = 0.572 |

| Participant confidence median (range), mean (sd) | 4 (3–4), 3.75 (0.38) | 4 (3–4), 3.78 (0.34) | V = 20.0, p = 0.821 | |

| T3a | Error rate | 17.5% (7/40) | 7.5% (3/40) | |

| Can [person x] see it? (when it is shared) | Participant errors median (range), mean (sd) | 0 (0–2), 0.35 (0.67) | 0 (0–1), 0.15 (0.37) | V = 16.0 p = 0.280 |

| Participant confidence median (range), mean (sd) | 4 (2.5–4), 3.82 (0.45) | 4 (3–4), 3.88 (0.28) | V = 9.0, p = 0.784 | |

| T3b | Error rate | 22.5% (9/40) | 10% (4/10) | |

| Can [person y] see it? (when it is not shared) | Participant errors median (range), mean (sd) | 0 (0–2), 0.45 (0.76) | 0 (0–1), 0.20 (0.41) | V = 22.0, p = 0.190 |

| Participant confidence median (range), mean (sd) | 4 (2.5–4), 3.79 (0.45) | 4 (3–4), 3.80 (0.34) | V = 13.0, p =0.930 | |

| E | Error rate | 12.5% (5/40) | 7.5% (3/40) | |

| Make it so that [person y] can/cannot see it. | Participant errors median (range), mean (sd) | 0 (0–2), 0.25 (0.64) | 0 (0–1), 0.15 (0.37) | V = 5.0, p = 0.572 |

| Participant confidence median (range), mean (sd) | 4 (3–4), 3.90 (0.31) | 4 (3–4), 3.90 (0.31) | V = 0.0, p = 1.00 | |

| Preference | Participant count | 15/20 | 5/20 | X2 = 5.0, p < 0.025* |

p<0.05

Following the same analytic approach used to assess errors made with the privacy icons, we compared the confidence level reported by participants who made errors on the sharing lists. For measures T1, T3a, T3b, and E, we compared the confidence participants reported on trials when they made errors versus trials when they made no errors. For transparency question T1 (i.e., Is it shared?), 4 participants made a total of 5 errors on the complete sharing list. There was no difference in confidence those 4 participants reported when they made errors versus when they did not. Three participants made a total of 3 errors on the selected sharing list. Only one of those 3 participants also made an error on the complete list. There was no difference in confidence when those 3 participants made errors and did not make errors on the selected list. For transparency questions T3a (i.e., Can person x see it?, when it is shared) and T3b (i.e., Can person y see it?, when it is not shared) together, 7 participants made a total of sixteen errors on the complete list. Of those 7 participants, 5 made a total of 7 errors on T3a and 6 participants made a total of 9 errors on T3b. Five participants made a total of 7 errors on the selected list. Of those 5 participants, 3 made a total of 3 errors on T3a and 4 made a total of 4 errors on T3b. There was no difference in confidence level for trials with and without errors for T3a or T3b on either list. Finally, for ease of use measure E (i.e., Make it so that [person y] can see it.), 3 participants made a total of 5 errors on the complete list and 3 participants made a total of 3 errors on the selected list. Only one participant made errors on both lists. There was no difference in confidence for trials in which participants made errors compared to trials in which they did not make errors for either sharing list.

Discussion

Our findings offer four important insights for meeting the information sharing needs of patients. First, participants’ sharing practices bolster prior research findings that people undergoing treatment for cancer share personal health information with a broad range of people in their social networks, and they do so to different extents depending on the type of social connection.2 This finding supports the need to incorporate granular sharing interfaces into consumer health informatics tools that support sharing in social networks.7

Second, we found that the lock icon was significantly more transparent than the megaphone icon as a quick overview of how information is shared, as illustrated by fewer errors made and higher confidence reported by participants with the lock icon. Further, participants unanimously preferred the lock icon over the megaphone icon. Thus, this compact, yet exact numeric rather than proportional, representation appears to provide an easier to understand interface that users are likely to prefer.

Third, we found that neither of the sharing lists we tested was more transparent or easier to use than the other. Although the majority of participants preferred the complete sharing list, additional exploration of granular designs for detailing and modifying sharing settings for personal health information is in order. Our findings support recommendations calling for further design work for usable sharing interfaces.12

Fourth, we learned that even with fairly simple sharing controls, patients’ judgments about whether and with whom information is shared are far from error free. Particularly alarming was the fact that 80% of participants made errors when interpreting the megaphone icon. Even the preferred lock icon was not error-free. It was disconcerting to watch participants make incorrect judgments about how sensitive health information is being shared, begging us to consider what level of error is acceptable? Furthermore, we expected that when participants made errors they would report lower confidence than when they did not make errors. However, this outcome was true only when participants used the megaphone icon to judge whether a piece of information was shared. Although our study yielded too few participants to determine definite trends, participants’ high confidence when errors were made is surprising. Outside the lab, such a situation risks devastating consequences of unintended disclosure and loss of anticipated privacy.

In summary, these findings support the need for interfaces that enable granular control over sharing personal health information in social networks, yet the sharing interfaces we tested are not overwhelmingly transparent or easy to use. Our work contributes important insights about usable privacy to the medical informatics and human-computer interaction communities, although our study has several limitations. First, a lab setting where we asked participants about a scenario with fictitious network connections could cause participants to be less invested than if they worked with their own data and social network. Second, many of our participants were well-educated and experienced computer users. Although results may have differed with a more diverse sample, the number of errors that occurred with our highly experienced participants was surprising. Future work could examine whether error rates differ when a more diverse and sufficiently large sample of participants works with their own personal health information. People think carefully about which pieces of health information to share with which people, devoting substantial effort into building and maintaining their sharing networks.7 Our findings shed light on advantages and limitations of technology for supporting those complex sharing needs.

Conclusion

Patients need tools that give them granular control over information they share with selected members of their social networks. Our work makes a step toward developing granular sharing controls that are both transparent and easy to use, thus minimize unintentional disclosure of sensitive personal health information. Yet, future work is necessary to create interfaces that are fully transparent. Bringing this goal to fruition will enable patients both to reap the benefits of using technology to keep their networks informed and to trust online systems with personal health information.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our participants for their valuable time and feedback and Patrick Danaher for assistance with statistical analysis. This work was funded by NIH grant R01LM009143.

References

- 1.Skeels MM, Unruh KT, Powell C, Pratt W. Catalyzing social support for breast cancer patients. Proc. of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’10); 2010. pp. 173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unruh KT, Unruh K. Information and the cancer experience: A study of patient work in cancer care. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2007. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss J, Lorenzi N. Online communication and support for cancer patients: A relationship-centric design framework. Proc. of the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) Fall Symposium; 2005. pp. 799–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markle Foundation Americans overwhelmingly believe electronic personal health records could improve their health. Jun, 2008. Available from: http://www.markle.org/publications/401-americans-overwhelmingly-believe-electronic-personal-health-records-could-improve-t.

- 5.Agarwal R, Anderson C. The complexity of consumer willingness to disclose personal information: Unraveling health information privacy concerns. eHealth Initiative’s 5th Annual Conference; Washington, DC. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weitzman ER, Kaci LK, Mandl KD. Acceptability of a personally-controlled health record in a community-based setting: Implications for policy and design. JMIR. 2008;11(2):e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman MW, Lauterbach D, Munson SA, Resnick P, Morris ME. It’s not that I don’t have problems, I’m just not putting them on Facebook: Challenges and opportunities in using online social networks for health. To appear in Proc. of the 2011 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourgeois FC, Taylor PL, Emans SJ, Nigrin DJ, Mandl KD. Whose personal control? Creating private, personally controlled health records for pediatric and adolescent patients. JAMIA. 2008;15(6):737–43. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caine KE. Supporting privacy by preventing misclosure. Proc. of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’09); 2009. pp. 3145–3148. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smethers DK, Good N. How users use access control. Proc. of the 5th Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS ’09); 2009. pp. 1–12. article 15. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazurek ML, Arsenault JP, Bresee J, Gupta N, Ion I, Johns C, et al. Access control for home data sharing: attitudes, needs and practices. Proc of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’10); 2010. pp. 645–654. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dourish P, Anderson K. Collective information practice: Exploring privacy and security as social and cultural phenomena. Human-Computer Interaction. 2006;21:319–342. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer L, Cranor LF, Reeder RW, Reiter MK, Vaniea K. A user study of policy creation in a flexible access-control system. Proc. of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’08); 2008. pp. 543–552. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boykoff N, Moieni M, Subramanian SK. Confronting chemobrain: an in-depth look at survivors’ reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3(4):223–232. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0098-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipford HR, Froiland K, Reeder RW. Visual vs. compact: A comparison of privacy policy interfaces. Proc. of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’10); 2010. pp. 1111–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Microsoft Health Vault www.healthvault.com/personal/index.aspx.

- 17.Skeels MM. Sharing by Design: Understanding and supporting personal health information sharing and collaboration within social networks. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2010. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holtzblatt KA, Jones S, Good M. Articulating the experience of transparency: An example of field research techniques. SIGCHI Bulletin. 1988;20(2):45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dourish P, Grinter RE, DeLaFlor JD, Joseph M. Security in the wild: User strategies for managing security as an everyday, practical problem. Personal Ubiquitous Comput. 2004;8(6):391–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klasnja P, Hartzler A, Powell C, Phan G, Pratt W. HealthWeaver mobile: Designing a mobile tool for managing personal health information during cancer care. Proc. of the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) Fall Symposium; 2010. pp. 392–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould JD, Lewis C. Designing for usability: Key principles and what designers think. Comm ACM. 1985;28(3):300–11. [Google Scholar]