Abstract

Researchers have conducted numerous case studies reporting the details on how laboratory test results of patients were missed by the ordering medical providers. Given the importance of timely test results in an outpatient setting, there is limited discussion of electronic versions of test result management tools to help clinicians and medical staff with this complex process. This paper presents three ideas to reduce missed results with a system that facilitates tracking laboratory tests from order to completion as well as during follow-up: (1) define a workflow management model that clarifies responsible agents and associated time frame, (2) generate a user interface for tracking that could eventually be integrated into current electronic health record (EHR) systems, (3) help identify common problems in past orders through retrospective analyses.

Introduction

There is a rich history of research on test result management in outpatient settings1,2. Researchers have conducted case studies reporting how many, why, where, which categories of, and at what step laboratory test results of patients were missed by the ordering primary care physician3,4. Authors analyzed the consequences of missing or delayed test results5. Not only did these authors look at current methods for coping with errors, and clinical personnel’s satisfaction with these methods, but researchers also asked them to suggest a solution to the problem6,7.

Prior research reports in great details about the problems and the importance of timely test results in primary care, therefore one might expect electronic test result management tools to be generally available to help medical staff during this complex process. Studies instead report that many institutions have their own way of handling test results and that there is no standard way8,9. Therefore, further research on the design of test result management and evaluation of their use in clinical settings could bring large benefits.

This paper presents three ideas to reduce missed results with a system that aids clinical personnel track laboratory tests from order to action completion. Our approach is to define agent temporal responsibilities using an easy to understand workflow management model, generate a user interface based on that model (that could eventually be integrated into current electronic health record (EHR) systems), and provide retrospective analyses that can help identify common problems in past orders.

Background on Issues in Ambulatory Test Result Management

Wahls6 defined missed results as “mishandling of abnormal test results”, which are then lost to follow-up. A study by Tang1 showed that in 81% of cases, physicians could not locate all the information to make informed patient care decisions during a visit. Among the unavailable data, the most common type of missing information was related to the result of laboratory tests/procedures (15–54%)10.

According to data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey of 2002, family physicians and general internists order lab tests in 29%–38% of patient encounters on average, and imaging studies in 10%–12%11. A physician in an internal medicine practice weekly reviews a mean of 930 individual chemistry/hematology tests and 60 pathology/radiology reports12. These tests are for screening or diagnostic purposes, or to manage and monitor medications and/or chronic health problems13. Although a few of the tests are performed in the office while patients wait, most patients or their samples are sent to outside locations such as standalone testing facilities or hospitals13. Results may be available during the same office visit or take weeks to obtain and do not have a universal format7.

It is not surprising that multiple testing locations, large number and variety of tests, as well as variable reporting processes would lead to delays and errors11. One study found that 83% of primary care physicians reported at least one delay in reviewing test results in the prior two months7. Patients can be and were seriously harmed by errors in results management5. According to a study by Hickner and colleagues5, adverse consequences of missing test results include delay in care (24%), time/financial loss (22%), pain/suffering (11%), adverse clinical consequence (2%). Patients were harmed in 18% of these instances while in 28% harm status was unknown. According to another report, failure to follow-up is in fact one of the fastest growing areas of malpractice litigation in outpatient medicine14. This, in turn impacts efficiency and effectiveness of treatment, patient safety, and overall satisfaction14.

It is not the lack of effort that causes many institutions and physicians to lose test results as significant time was spent searching and managing test results15. It seems that the complexity of the process, separation of lab from clinic location, variations in reporting processes, and lack of quality control systems in outpatient setting make testing error-prone5. Wahls and Cram16 pointed out that there are no established standards as how best to manage test results. Yackel et al.2 studied current information systems used for tracking and found there were interface and logic errors in results routing, physician records, system setting interfaces, and system maintenance tools. Even when physicians did have reliable methods, medical staff did not routinely check for pending orders without results9. Thus, less than one-third of physicians were satisfied with how they managed test results14.

Research studies also revealed the desired features of an electronic test result management system. Most of them found out that a tool to generate and send result letters with predefined texts to patients via email is the highest-rated feature of a potential results management system7,16. Physicians wanted to acknowledge all test results electronically through an “in-box” function7. Another most desired capability concerned the prioritization of diagnostic results such that abnormal ones are shown before normal results and the built-in review prompts support the physician to make a decision and take further action7,16. Physicians also suggested tracking their orders to completion, i.e. a warning mechanism to detect whether ordered tests have not been completed7. Finally, physicians requested delegation of responsibility to other staff16. More specifically, they desired a forwarding capability to allow the use of surrogates during planned absences and a consistent process for designating proxies when they are unavailable7,16.

Methodology for Prototype Development

There are multiple steps involved in the management of test results11. They begin when a medical provider orders a test and end when the results are acted upon. Previous research5,11 has grouped the overall test process into three major phases, which also include several sub-steps. In that model, the processing of tests is defined sequentially. In other words, a laboratory test cannot be performed if the patient’s blood or urine is not collected first. Hickner and his colleagues11 listed the problems that might occur in the testing process as follows:

- Pre-analytic

- Ordering the test

- Implementing the test

- Analytic

- Performing the test

- Post-analytic

- Reporting results to the clinician

- Responding to the results

- Notifying the patient of the results

- Following-up to ensure the patient took the appropriate action based on test results

Based on this, a formal process model that represents a lab test management workflow can be defined. Such a process model needs two components: (i) agents that interact with each other to finish the assigned work, which is not clear in Hickner’s model since the actors are not explicitly defined, (ii) because delay is an issue, time constraints, which do not exist in Hickner’s model. Thus, we define agent temporal responsibility as “every actor of a process is assigned an associated duration during which they complete their own task”.

The authors11 suggest that standardization of collection, preparation, and delivery of specimens could solve ordering and implementation problems. To help with tracking and returning issues they recommend increasing the quality of communication via dual tracking between the lab and physician’s office. Specifically, they describe a backup fail-safe system that records all tests requested, sent, received, and completed. In addition, a computerized test tracking system integrated into an EHR is suggested for response and documentation mistakes11. To avoid patient notification errors11, auto-generated letters and voice systems may aid in communicating results. This research confirms the need for a complete tracking interface that provides users continuous feedback on test progress and results.

As described in the background section, many errors inevitably occur. In safety research, it is important not only to act on errors currently occurring, but also to identify issues likely to happen next and to understand how to prevent them17. According to this, obtaining a high level of understanding of the situation improves the ability to forecast future events and dynamics. Since a computerized system that records all tests seems as the best solution to the problem, we propose using the stored data to retrospectively analyze the delays that happened in the past. This enables a user to understand the steps issues aroused in the past and the responsible people. The user can also learn from collective knowledge, classify general issues, and prevent prior problems from reoccurring.

Process Model

We developed a prototype to refine our ideas and present to clinical providers, designers, and medical managers. This prototype runs as a Java application and consists of 43 classes, each ranging of between 100 and 500 lines. Our first contribution to solve the missing results problem is a workflow model that defines responsibility for different time periods during the lifetime of a sequential test process. In our model, every test is a process, which may contain multiple sub-processes, i.e. tasks, handled by various actors. These actors have supervisors who will get notified when a delay occurs. Every task has an associated duration range to capture how long it is expected to take.

The workflow model is specified in an eXtensible Markup Language (XML) file that is read by the running application. Every process may have any number of actors that indicate the roles of responsible agents. One actor can perform one or more tasks, i.e. sub-processes of the main process. For a task, there may be certain options to execute, tagged as action in our model. A process requires a unique id and a name. Actors have a role attribute denoting their role in the system. A task is defined with a required unique id, a name, start, end, and unit. The start and end attributes take numeric values, while unit can be any of “mins”, “hours”, “days”, “weeks”, “months”, or “years”. An action has a required unique id, a type, actor, process, and object. A type can be assigned to one of “order”, “consult”, “refer” values; actor captures a role; process means an id of another process from the same file; object can be a workflow artifact used in the system such as a medication.

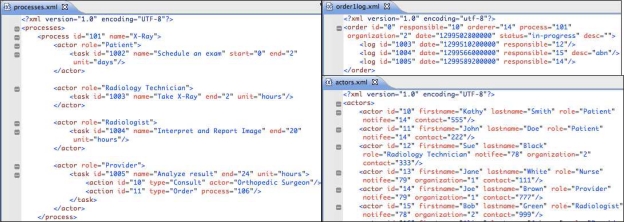

An example process is shown on the left of Figure 1. Here the process is an X-Ray study. In this example, the patient is expected to schedule an exam with an imaging center or radiology department within 2 days. After the patient shows up at the center, the Radiology Technician takes the X-Ray between 0 and 2 hours. The radiologist then has 20 hours after the study is performed to interpret and report images to the ordering physician. Following the arrival of these results to the office, the physician has 24 hours to act upon them. During result review, the physician can be guided to particular process-specific actions. For an X-Ray (Figure 1), these are consulting an Orthopedic Surgeon and/or ordering another test, such as a different set of X-Rays, shown here by “process=‘106’”.

Figure 1.

Test processing model for a generic X-Ray study (on the left), a sample X-Ray order file (upper right), and some of the actors in the system showing those involved in the X-Ray order (bottom right).

To demonstrate the tracking user interface in action we needed to simulate the placement of the orders. Our simulator reads a set of XML order files. An order file is similar to a log file that would be replayed at higher speed by the simulation. It contains all the information about an order’s lifecycle and status, i.e. pre-determined tasks done at pre-specified times. The upper right of Figure 1 illustrates an example file for an X-Ray order. It shows that Kathy Smith is the patient, Joe Brown is the ordering provider, and that Washington Lab had been chosen to conduct the test on March 7, 2011 at 8 AM. The process id is taken from processes.xml. On the other hand, each id, assigned for responsible or orderer attributes in order1log.xml, is listed inside actors.xml on the bottom right of Figure 1. A log is made for every step taken during the processing of an order. In Figure 1, on March 7, 2011 at 10:03 AM the Radiology Technician, named Sue Black, performs the task “Take X-Ray” indicated with the task and log id = “1003” in processes.xml and order1log.xml, respectively. Then, Bob Green, who is a Radiologist, interprets and reports the images with an abnormal flag. Finally, the provider Joe Brown analyzes the results.

The bottom right of Figure 1 displays a partial actors.xml file depicting actors registered with the system. An actor has a required unique id, firstname, lastname, role, notifee, organization, and a contact. A notifee, which denotes a supervisor who gets notified when something goes wrong, is another actor from within the same file encoded here with the id. An example is the patient, Kathy Smith, whose primary care provider is Joe Brown and has a contact #555 (Figure 1). Another example is the Radiology Technician, called Sue Black, from Washington Lab (see organization attribute), whose notifee is the laboratory manager of Washington Lab, Amy Powell (not shown in Figure 1).

User Interface

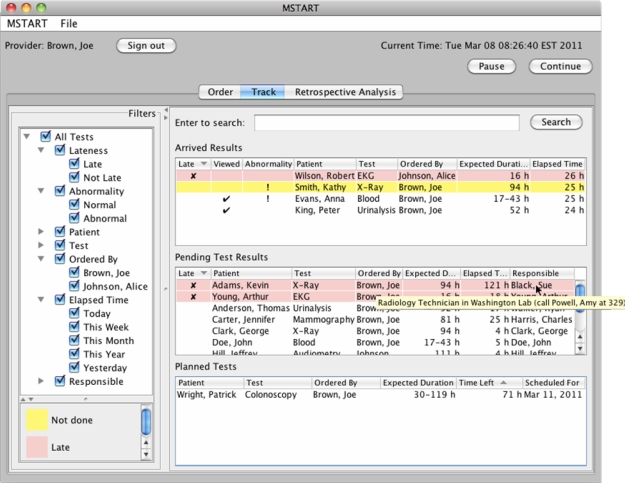

The user interface of our prototype application has three tabs for three screens (1) order, (2) track, and (3) retrospective analysis as can be seen in Figure 2, with the tab “Track” being selected. The prototype requires users to login and depending on their role, they see a different screen and data pertaining to their responsibilities. By default users only see the work assigned to them. Figure 2 shows the “Track” screen of an ordering medical provider (Joe Brown, as shown on the upper left corner), but his colleague Alice Johnson is in vacation so he can see her results as well. Note that the screenshots show simple situations with few tests to facilitate explanation but our design is intended to scale up to large caseloads and to the rich complexity of medical care.

Figure 2.

Tracking screen of the prototype. The table shows arrived, pending, and planned tests. Color-coding shows lateness. Filters allow clinician to customize the display (e.g. show only tests that are late, or include the tests ordered by a colleague now in vacation).

In the order screen, ordering clinicians would order tests, see the estimated duration of a test and mark their orders urgent if desired. They may set a later date for their order if the test is planned in advance. They can also indicate which laboratory facility they want the patient to visit.

This simulation advances time rapidly to show how the system would work in a real setting as orders become active. On the top right of Figure 2, there are pause and continue buttons to stop and start the simulation. Tests that came back to the physician are listed in “Arrived Results” table, while tests that are currently pending (i.e. in progress but not returned to the ordering physician yet) are shown under “Pending Test Results”. Arrived results that are late to be acted upon are marked “x”, viewed results are marked with a tick sign, and abnormal results are indicated by an exclamation mark. In the arrived results table, a pink background shows lateness (lateness is calculated using order time, expected duration, and current time). For example, Robert Wilson’s EKG is late to be reviewed and acted upon (Figure 2). Results that are not late but remain to be viewed are shown in yellow, such as Kathy Smith’s abnormal X-Ray (Figure 2). When the result has been viewed, the background color turns to white as in the case of Anna Evans’ blood test (Figure 2). Tests are removed from the list only when some action has been taken and the provider has signed off on the results. The color legend on the bottom left (Figure 2) helps users learn the color-coding.

The arrived results table shows abnormality information and whether or not the physician has viewed the test, namely whether the physician read the results but did not take all follow-up actions yet. There is no column for responsible person in arrived results because the logged in user is responsible. Filters on the left side also allow the user to filter out what is shown in the list, for example, they can choose to only show tests that are late.

In the pending tests table, late tests are also highlighted with a pink background. The columns for pending tests are lateness, patient name, test name, ordering physician name, expected duration for the test (calculated from its model definition), elapsed time, and name of the responsible person (who is currently in charge of handling the test). Hovering over actors with a mouse shows the role of the person, their institution as well as their manager’s name and contact information as a tooltip. In Figure 2, we observe that the X-Ray result of Kevin Adams is late, and we can see that Sue Black is the person responsible for the current step of the process. The tooltip shows that she is a Radiology Technician in Washington Lab, whose supervisor is Amy Powell with contact number, 329. This allows the provider (or his assistant) to see who is responsible for the lateness and to take action by calling their supervisor.

Tests that are ordered for the future are listed in the “Planned Tests” table. The table shows the remaining time for the test to be started, as well as the scheduled date for the test to be performed. When the time is up for planned tests, the entries move to pending test results and are no longer listed in the bottommost table. Similarly, as the result of a pending test return back to the ordering physician, the entry in the pending table moves up to the arrived results.

All tables are sorted by default so as to visually aid users see important results at the top: (i) Arrived results are listed in order by lateness, viewed status, abnormality, and patient. Thus, late results appear at the top, results that are not viewed are listed later (since they have high possibility of being forgotten by the physician), then abnormal results are shown, and finally results of the same patient are grouped together. (ii) Pending tests are ordered by lateness first, then by patient name, and test lastly. (iii) Planned tests are shown with first priority given to time left for processing (sooner ones go up in the table), secondly with a priority on patient name and thirdly, on test so as to group similar tests together. The user may customize the default sorting by clicking on the headers of any column. An arrow on the header indicates ascending/descending order. In Figure 2, Robert Wilson’s late EKG is at the top of the table, while Kathy Smith’s unviewed abnormal X-Ray comes next, after that viewed abnormal blood test of Anna Evans appears, and finally viewed normal urinalysis test of Peter King is listed.

Reviewing Results and Taking Action

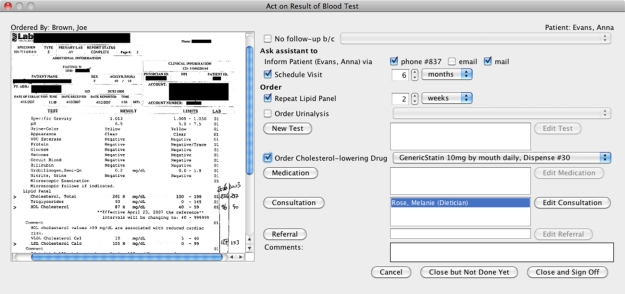

When the user double clicks on the rows in any of these tables, another window appears. In our prototype, we advocate integrating follow-up actions with result review. The list of possible actions depends on the role of the logged in user. An example of result review for a blood test is shown in Figure 3, which presents the actual test results on the left. Interacting with the main window (Figure 2) is disallowed until this window is closed. From Figure 3, physicians can pick a predefined reason from a list of options if no follow-up is necessary. Physicians can ask their assistant to inform the patient (by one of the default options) and/or schedule a visit. In Figure 3, phone (along with patient’s contact number) and mail are chosen to inform the patient, Anna Evans.

Figure 3.

When results are presented (on the left), a menu of follow-up actions is available (right side of the screen). Users can select actions and “Close and Sign Off” to finalize follow-up or “Close but Not Done Yet” if the follow-up is not complete yet.

Custom actions, defined in the model for this blood test, are shown here to allow the user choose amongst them easily. The first action is to simply repeat the current tests, a lipid panel (blood work looking at cholesterol levels) and urinalysis (urine test). In the process model of a blood test, ordering a urinalysis test and cholesterol-lowering drug as a medication were specified so the physician may select them here. If none of these are applicable, the physician can choose a standard action such as ordering other medication or a new test. “Medication”, “New Test”, “Consultation”, and “Referral” buttons take users to standard order screens implemented in EHR systems. Already taken actions are listed next to the corresponding buttons (e.g. the consultation requested from dietician, Melanie Rose, in Figure 3) to remind the physician and allow them to edit or cancel those actions through standard screens. It is expected to improve efficiency and reduce memory load to have the most frequent actions as one-click buttons.

Clicking “Close and Sign Off” indicates completion, i.e. the result was viewed and all of the follow-up actions were taken and the result could be removed from “Arrived Results” list. On the other hand, when the physician presses “Close but Not Done Yet” button, it means the result was viewed and/or some follow-up actions may have been taken but not all. Such a result is kept in “Arrived Results” table for further processing but is marked as “viewed”. “Cancel” button closes the window without affecting anything in cases when the physician unintentionally opened an arrived result by mistake or wants it to remain as unviewed; the actions are not saved either.

Retrospective Analysis

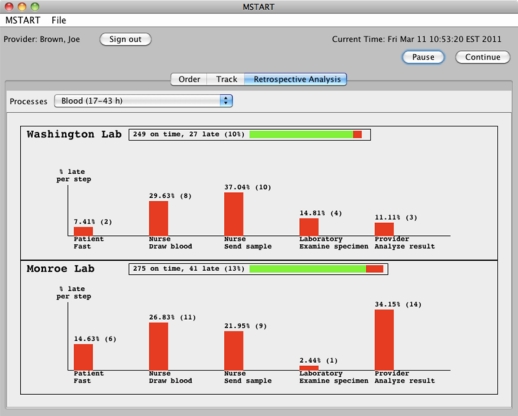

The third screen (Figure 4) presents a retrospective analysis of all archived orders. It allows users to see in detail which laboratory facilities did a better job in the past in terms of timeliness of each actor as compared to specified duration in the model and the amount of tests returned. Currently, if any step in the process was delayed, the test is flagged late and the bar chart displays these delayed steps only. The idea is to give the user some feedback on common problem cases and compare side-by-side performances of various outside facilities. Once the physician selects a test (from the combo box labeled Processes in Figure 4), the facilities that perform that test are listed one below the other. In the example of Figure 4, Washington and Monroe Lab are two facilities that perform blood tests.

Figure 4.

Retrospective analysis of Blood tests performed at Washington and Monroe labs.

The total number of tests performed at a particular lab is shown next to the name of that lab. In Figure 4, the reader can see that 249 blood test orders sent to Washington Lab were marked on time and 27 were late (10% of all blood tests performed there) due to various reasons. The length of the horizontal bar next to the name of the facility repeats this information; green depicts being on time while red is used for lateness. Each facility has a bar chart showing the percent (out of all the late tests from that institution) and the number of tests that were delayed at a particular step of that test. These steps are taken from the model definition. For instance, from Figure 4, one can see that the fourth step of a blood test is the examination of the specimen by a laboratory technician. The comparison of the corresponding two vertical bars in Figure 4 reveals that 14.81% (4 out of 27 test) were due to Washington Lab’s personnel while 2.44% (1 out of 41 tests) were because of technicians in Monroe Lab. Thus, Monroe Lab was timelier in past results although a higher percent (13%) of blood tests sent there had a late step.

Initial Evaluation

Following a user-centered approach of iterative design and evaluation we conducted regular meetings with clinicians who provided feedback on the interface prototype as well as on our general design principles. More than a dozen physicians provided feedback at seven different events for an estimated total of about eight hours of review and discussions over five months. These were structured as a demonstration of the prototype or presentation to a group of people who are knowledgeable in any of medicine, human-computer interaction, or software engineering areas. Here, we discuss key expert comments and will conduct further evaluations as the prototype matures. We will pursue integration of these features in commercial products, so as to demonstrate the value of these strategies.

All of the experts approved of the idea to have an explicit workflow model to calculate expected durations of laboratory tests and of the notion of explicit responsible agents. They requested improvements to the model to capture repeat testing, such as blood drawn once a week for two months. Another recommendation was regarding reflex tests, where one test can automatically lead to a second test. In addition, abnormal results could sometimes take longer to process, and we discussed how results are not processed at the same speed every weekday so calculations of temporal aspects should take this into account. Customized (possible) actions for process steps were also among the ideas considered during one of our demos.

There were many suggestions about our user interface generation. Terminology used on screens has been updated several times based on comments from medical experts. There were also refinements to the interface such as adding or removing functionality to make its intended use clear. For instance, when we presented our idea of responsible agents, it did not make sense to see only the name of a person. By discussions, we decided to have a manager in the model that gets notified and the manager’s contact information should be displayed along with responsible person’s role as a tooltip. The incorporation of another table for planned orders, which have been entered into the system for future testing (such as 3 years from now) but are not currently being processed and cannot be listed either as arrived or pending, was completed after another physician’s question.

The idea of a retrospective analysis was well received and found to be helpful to quickly quantify general problems. However, domain experts expected to see how late the results were besides the fact that some were late. To see more information was useful and most domain experts were interested in seeing more data to track (as physicians are responsible for hundreds of tests daily) and analyze. One interesting proposal was to have quality attributes built into our model so as to compute some metrics for later analyses.

Related Work

Two relevant areas of research inspired our work: test result management tools and workflow process models.

Test Result Management

Some methods that clinical personnel use to track their test results are still through paper charts13. Most research reports only suggest general-purpose alternatives such as logbooks16 or checklists7 rather than an application tiered to the task. To the best of our knowledge, the state-of-the-art for test tracking is a system called Results Manager by Partners Healthcare12. It organizes laboratory tests around patient visits and does not let individual tests to be listed. Users can see all (currently open and closed) visits, flag them, and add to their watchlist. Chemistry, hematology, radiology, and pathology tests are the only supported types of tests so the addition of new tests or the modification of existing ones is not supported. Abnormality has three degrees: critical, abnormal, and normal. Through patient charts, physicians may acknowledge a result, add a visit note, or generate patient result letters although researchers reported that automatically generated papers sometimes make no sense and are typically not useful8.

This tool has a complex user interface since the user has to switch between the Manager screen where all visits are listed and patient charts where the result details are. It is not easy to learn either because all numerical results are listed in a table format that could easily be overlooked even with color options supported (red for high, blue for low abnormal result). Although clinicians may mark results with reminders for future follow-up tests, but follow-up decisions are left to the provider. It is not obvious where to see individual late results immediately and act upon that. It does not support interfaces for participants other than the provider that are actively involved in the testing process.

Workflow Process Models

We based our test process model on other well-known workflow process models. Models that have multiple participants such as various actors involved in test processing and also have a notion of temporal aspects, as medical data is very time-sensitive, were of special interest.

Ling and Schmidt applied time workflow (Petri) nets to an example from a Patient Workflow Management System (PWfMS)18. They define firing time interval and show that some transitions are reachable only after certain time has passed. In their example, some places are labeled as actors while transitions, which are assigned durations, represent task steps. Because some places are not labeled, it is not clear who is responsible from the tasks executed. Later, authors describe in detail how to manage resources of a role. This model does not seem to constrain the total time but according to the authors, some existing algorithms can calculate the longest and shortest process instance in a workflow given the temporal requirements.

Little-JIL19 is a process definition language used to model medical processes. In the paper, authors identify process defects and vulnerabilities that pose safety risks by creating a detailed and precisely defined model of a medical chemotherapy process with Little-JIL. Applying rigorous automated analysis techniques to this model leads to an improved process that is reanalyzed to show that the original defects are no longer present. The main difference between Little-JIL and our approach is that the models created and proven in Little-JIL are the end result. Our focus is on using the model as a means to generate user interfaces for actors participating in laboratory test processing.

Computer-interpretable clinical guideline modeling languages20,21,22 have gained interest in the recent past and many languages have been developed including machine-executable ones that come with tools to support authoring and editing as well as enactment. A medical guideline is a document with the aim of guiding decisions and criteria regarding diagnosis, management, and treatment. We depart from these approaches because medical guidelines refer to medical science only and do not stipulate a process or a schedule for performing medical services. Hence, they are not the subjects of instantiation for an individual treatment. Clinical pathways, also called care pathways, have been introduced to overcome these drawbacks. They use medical guidelines to define and sequence different tasks by healthcare professionals. For instance, Noumeir23 describes the model of a radiology interpretation process. However, the models are usually specific to a particular process and cannot be generalized to a class of processes.

Time-BPMN24 is an extension of Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN), used for analyzing/improving business processes of an enterprise. It captures temporal constraints and dependencies that might occur during real-world business processes. It is a complicated model for medical domain since constraints like As late as possible (ALAP) has very little use for clinicians as most tests are desired to have completed As soon as possible (ASAP), No later than (NLT), No earlier than (NET), or On some time. One limitation of this approach discussed in the paper is it does not allow for multiple start/finish constraints. This makes it harder to describe branches or repetitions that might be useful for laboratory tests. The authors leave it to the scheduler (if one exists) to find a consistent schedule, which satisfies all constraints and dependencies. This results in non-deterministic instantiations since various scheduler implementations will output different schedules. We take another approach and compute the total finish time based on given constraints so that the user cannot misuse the notation.

Conclusion and Future Work

Our focus is on reducing missed laboratory results by developing a medical workflow model that defines temporal responsibility in test result management. We described our implementation of a prototype user interface for test process tracking, and our ideas on retrospective analyses for identifying problems. Our argument is that by showing what is missing and how much time has passed since the last action, responsible agents could be easily determined. Also prioritization of lateness and abnormality, and support for follow-up actions within the same screen is expected to improve efficiency. Our goal was not to develop a working system, but to provide an inspirational prototype that demonstrates our design principles, thereby enabling developers of commercial and proprietary medical management tools to implement their version of these ideas. We initially focused on ambulatory care but future work will test how the model can be adapted to hospital settings or the coordination between multiple providers taking care of a patient. While a usability study is possible, we are more interested in demonstrations for professional developers and adoption of these principles, which could then be subjected to controlled, usability, ethnographic, or data logging studies in the context of primary care physicians doing their daily work.

We continue gathering feedback from clinicians to refine our analysis of what is necessary for a complete tracking interface. We will improve our user interface to allow setting/saving controls and showing options for different users via a preferences dialog. We are also looking into design choices for a better retrospective analysis that indicates the severity of issues aside from the fact that some issues simply exist. Moreover, lateness computations could be improved. When a test should be declared “late” is a subject of discussion. One could argue that it is only important to report that the overall test is delayed. However, cases when all steps are fast enough to compensate for the lateness of one person/facility would then be overlooked. Also, should a test whose results arrived late be marked as late even if the ordering physician who is now responsible for its review has not had a chance to review it? Should user options be provided to define lateness, or should only a standard definition be proposed?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grant No. 10510592 for Patient-Centered Cognitive Support under the Strategic Health IT Advanced Research Projects Program (SHARP) from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

References

- 1.Tang PC, Fafchamps D, Shortliffe EH. Traditional Medical Records as a Source of Clinical Data in the Outpatient Setting. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1994;18:575–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yackel TR, Embi PJ. Unintended Errors with EHR-based Result Management: A Case Series. JAMIA. 2010;17(1):104–7. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boohaker EA, Ward RE, Uman JE, McCarthy BD. Patient Notification and Follow-up of Abnormal Test Results: A Physician Survey. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:327–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh H, Thomas EJ, Sittig DF, et al. Notification of Abnormal Lab Test Results in An Electronic Medical Record: Do Any Safety Concerns Remain? Am J Med. 2010 Mar;123(3):238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickner J, Graham DG, Elder NC, et al. Testing Process Errors and Their Harms and Consequences Reported from Family Medicine Practices: A Study of the American Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(3):194–200. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.021915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahls T. Diagnostic Errors and Abnormal Diagnostic Tests Lost to Follow-Up: A Source of Needless Waste and Delay to Treatment. J Ambul Care Manage. 2007;30(4):338–43. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000290402.89284.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poon EG, Gandhi TK, Sequist TD, Murff HJ, Karson AS, Bates DW. “I Wish I Had Seen This Test Result Earlier!”: Dissatisfaction with Test Result Management Systems in Primary Care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2223–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some Unintended Consequences of Information Technology in Health Care: The Nature of Patient Care Information System-related Errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104–12. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elder NC, Meulen MV, Cassedy A. The Identification of Medical Errors by Family Physicians During Outpatient Visits. Ann Fam Med. 2004 Mar-Apr;2(2):125. doi: 10.1370/afm.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dovey SM, Meyers DS, Phillips RL, et al. A Preliminary Taxonomy of Medical Errors in Family Practice. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:233–8. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickner JM, Fernald DH, Harris DM, Poon EG, Elder NC, Mold JW. Issues and Initiatives in the Testing Process in Primary Care Physician Offices. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005 Feb;31(2):81–9. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poon EG, Wang SJ, Gandhi TK, Bates DW, Kuperman GJ. Design and Implementation of a Comprehensive Outpatient Results Manager. J Biomed Inform. 2003;36(1–2):80–91. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0464(03)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elder NC, McEwen TR, Flach JM, Gallimore JJ. Management of Test Results in Family Medicine Offices. Ann Fam Med. 2009 Jul-Aug;7(4):343–51. doi: 10.1370/afm.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murff HJ, Gandhi TK, Karson AK, et al. Primary Care Physician Attitudes Concerning Follow-up of Abnormal Test Results and Ambulatory Decision Support Systems. Int J Med Inform. 2003;71(2–3):137–49. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing Clinical Information During Primary Care Visits. JAMA. 2005;293(5):565–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wahls TL, Cram PM. The Frequency of Missed Test Results and Associated Treatment Delays in A Highly Computerized Health System. BMC Family Practice. 2007;8(1):32–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh H, Petersen LA, Thomas EJ. Understanding Diagnostic Errors in Medicine: A Lesson from Aviation. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:159–64. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dazzi L, Fassino C, Saracco R, Quaglini S, Stefanelli M. A Patient Workflow Management System Built on Guidelines. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:146–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christov S, Chen B, Avrunin GS, et al. Formally Defining Medical Processes. Methods Inf Med. 2008;47(5):392–8. doi: 10.3414/me9120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shahar Y, Miksch S, Johnson P. The Asgaard Project: A Task-specific Framework for the Application and Critiquing of Time-oriented Clinical Guidelines. Artif Intell Med. 1998;14:29–51. doi: 10.1016/s0933-3657(98)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peleg M, Boxwala AA, Ogunyemi O, et al. GLIF3: The Evolution of A Guideline Representation Format. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 2000:645–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox J, Johns N, Rahmanzadeh A, Thomson R. PROforma: A Method and Language for Specifying Clinical Guidelines and Protocols. Proc Med Inform Europe; Amsterdam. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noumeir R. Radiology Interpretation Process Modeling. J Biomed Inform. 2006;39:103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gagné D, Trudel A. Time-BPMN. IEEE Conference on Commerce and Enterprise Computing; 2009. pp. 361–7. [Google Scholar]