Abstract

Adverse drug events (ADEs) create a serious problem causing substantial harm to patients. An executable standardized knowledgebase of drug-ADE relations which is publicly available would be valuable so that it could be used for ADE detection. The literature is an important source that could be used to generate a knowledgebase of drug-ADE pairs. In this paper, we report on a method that automatically determines whether a specific adverse event (AE) is caused by a specific drug based on the content of PubMed citations. A drug-ADE classification method was initially developed to detect neutropenia based on a pre-selected set of drugs. This method was then applied to a different set of 76 drugs to determine if they caused neutropenia. For further proof of concept this method was applied to 48 drugs to determine whether they caused another AE, myocardial infarction. Results showed that AUROC was 0.93 and 0.86 respectively.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines pharmacovigilance as “the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or to other possible drug-related problems.”1 Current surveillance systems have been developed to analyze large databases containing adverse event reports, such as the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS)2, European Medicines Agency3 and WHO. Proportional reporting ratio (PRR)4 and Bayesian data mining methods5–7 are widely used to automatically detect novel adverse drug event (ADE) signals in these databases. There are several issues concerning these efforts. One problem is that most adverse drug events detected by physicians and patients are not reported to these agencies because reporting of adverse events is required only for the drug manufacturers, and therefore the incidences are significantly underestimated. Another problem is that data mining high volume databases can result in large numbers of potential drug-ADE pairs, which then need to be categorized into known and unknown groups manually. This is a time consuming process, which could be expedited if a database of drugs related to a certain adverse event phenotype were available. Micromedex8 is an excellent resource, which contains high-quality information concerning ADEs, but is proprietary, not freely available to the public, and is not always up to date. SIDER9 is another drug-ADE knowledgebase which was obtained by extracting drug-ADE information from drug labels, and it is publicly available. But it is likely to have a substantial number of questionable entries for two reasons. One reason is that many of the drug-ADE pairs were gathered using natural language processing of online textual drug labels based on a straightforward pattern matching method, which therefore would be likely to result in a number of errors. The second reason is that the labels themselves usually contain a long list consisting of adverse events reported during clinical trials of the drugs. Although those events were reported to have occurred during a trial, they were not necessarily caused by the drug. For example, Atorvastatin has over 120 side effects listed in SIDER, but only some of them are actually ADEs.

The biomedical literature contains articles reporting on drug-ADE relationships, and can be used as a resource to detect such relationships. PubMed10 contains millions of citations concerning the biomedical literature from different journals. Citations also contain MeSH headings which are added to the articles based on manual curation of experts. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)11 is the National Library of Medicine’s controlled vocabulary thesaurus that are used to represent primary concepts associated with the articles. Thus headings may contain diseases, such as neutropenia as well as the names of medications. Headings also may have subheadings, which are also called qualifiers that can be attached to MeSH headings, and describe a specific aspect of a concept. For example, “adverse effects” and “chemically induced” are frequently found in the subheading lists, and are useful features for detecting drug-ADE relationships. Most articles in PubMed contain abstracts written in English, and simple text analysis of the abstracts could also provide a set of features to help detect drug-ADE relations. Other research has been conducted to extract information from the biomedical literature. Srinivasan and Rindflesch12 introduced eight relationships from the biomedical literature, such as “treatment cures disease” and “disease is a result of a treatment”. Data mining methods13–14, such as neural networks and statistical graphical models have also been designed to find drug relationships from the biomedical literature. But these methods were all designed to extract information at the level of individual sentences, whereas our work aims to determine the likelihood of a specific drug-ADE relationship based on the classification of multiple documents associated with the pair.

The objective of our research is to develop a method to extract knowledge from PubMed that determines drug-ADE relationships which could then be used to create a knowledgebase for known drug-ADE relationships to support pharmacovigilance and decision support. In this work we focus on two serious adverse events but our ultimate goal is to extend the methodology to a set of 23 serious adverse events15, which were selected by an expert panel as being the most important for pharmacovigilance.

Methods

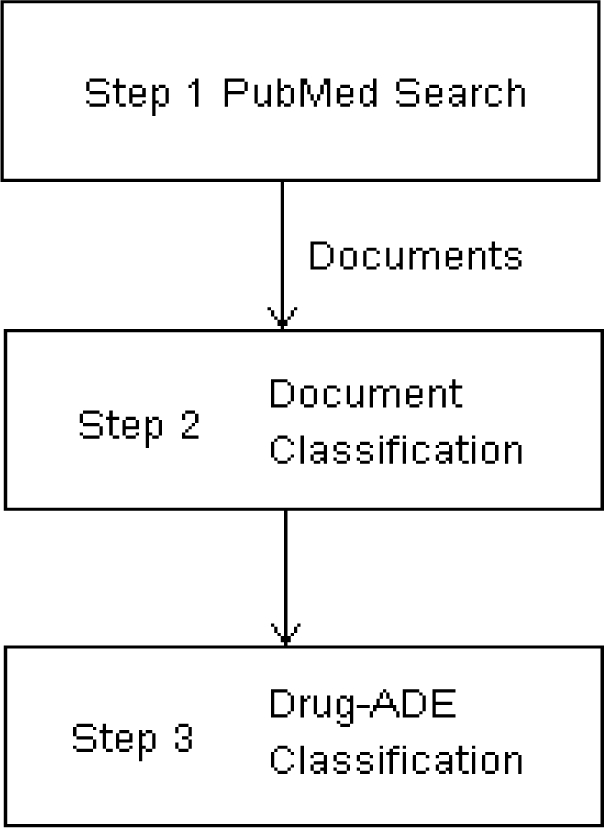

We choose a serious adverse event neutropenia as a target adverse event to develop the drug-ADE detection algorithm, but other adverse events could have been used to develop the algorithm as well. Neutropenia is a blood absolute neutrophil count that is two standard deviations below the normal population mean19. Patients with neutropenia are at higher risk of life threatening infections, and there are number of nonchemotherapy drugs that are known or suspected to cause neutropenia20. The entire pipeline for the overall process is illustrated in Figure 1. Step 1 involves a PubMed search to retrieve articles containing terms associated with a given drug-ADE pair, e.g., neutropenia and the drug docetaxel. Step 2 involves classification of individual documents, and step 3 involves classification of the drug-ADE relation based on classification results of the retrieved articles. In step 2, each of the retrieved articles is individually classified as denoting or not denoting the drug-ADE relation. In step 3, it is determined whether the drug likely caused the ADE using the results of the step 2, namely by considering the articles that were positively classified. The details are explained below.

Figure 1.

The pipeline of the drug-ADE detection algorithm.

Data set creation:

25 drugs were selected by a physician, where 16 were known to cause neutropenia and 9 known not to cause neutropenia. After querying each drug and neutropenia pair for the 25 drugs using PubMed, more than 13,000 articles were retrieved, and from that set, 600 articles were randomly selected. Each article was reviewed by one of three experts to form a gold standard data set, where each expert reviewed a total of 200 articles. We removed duplicate articles as well as articles which could not be definitively classified by the experts. From the remaining articles, we randomly choose a data set totaling 400 articles, which consisted of 200 positive cases denoting that the drug caused neutropenia, and 200 negative cases where the articles did not denote that the drug caused neutropenia. This dataset of 400 articles was used to train and test the classifier.

Feature extraction:

The retrieved articles were in an XML format, containing tags corresponding to the different sections, such as title and abstract, and metatags, such as MeSH headings, substance names, and publication type. Two sets of features were extracted: ontological features and textual features and they were listed in Table 1. Ontological features were extracted based on MeSH headings and subheadings, and also included publication related entities and chemical compound related entities. Twenty-one ontological features were extracted, where some were binary and some were multi-value discrete. For example, the second variable of the ontological features in Table 1 is a binary variable, which was set to a 1 if the article was a case report, and to 0 otherwise, and ninth variable is a multi-value discrete variable, which is a numeric value based on the number of occurrences of the MeSH subheading adverse effects in the article. Fourteen simple textual features were extracted from the text of the title and abstract. In order to increase performance, we considered drug names for both generic and brand names and performed stemming of certain keywords. For each drug, generic name was provided and RxNorm16 was used to determine the brand names. For example, for vinorelbine, we considered its brand name navelbine as well. For symptoms, we also considered synonyms and variants, and used simple regular expressions. This approach affects the textual feature extraction and would have to be delineated differently for each different ADE. For example, for neutropenia, we also considered the “neutropeni*”, “agranulocyt*”, “bone marrow supress”, “supress bone marrow”, “leukopeni*” and “granulocytopeni*” by checking with UMLS and Cochrane collaboration systematic reviews. For the current work, searching the synonyms and variants of symptoms was not automated since there were no such database and we had to check for every symptom manually. Abbreviations are widely used in biomedical literatures, such as human immunodeficiency virus, which was frequently referred to in the abstracts as HIV. Abbreviations which were defined within the abstract were also considered as being the same as the corresponding full form of the drug or symptom when obtaining the features. In the title and abstract, there were several words, which often denoted that the drug causes an ADE, which also helped classify the article. For example, induced is a positive keyword in the sentence “Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and treatment efficacy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of three randomised trials”. After consulting with physicians, we found the following positive key words “toxicity”, “adverse”, “side effect”, “develop”, “induce”, “tolerate”, “risk”, and “complicate”, which were then stemmed. Since there were only eight key words, we designed regular expressions for stemming manually. For example “toxici*” was used to represent “toxicity” and “toxicities”. With the above processing step, 14 textual features were extracted. The first variable in textual set would be set to 1 if the title contained the drug name and to 0 otherwise. The last variable in the textual set represented the number of sentences which contained the drug name, neutropenia, and some positive key words.

Table 1.

Features extracted from retrieved articles. “key” represented positive key word.

| Ontological features | year published |

| case report | |

| journal article | |

| review | |

| Cochrane review | |

| drug appeared in the chemical list | |

| numbers of chemicals | |

| human subject | |

| number of occurrences of “adverse effects” | |

| number of occurrences of “chemically induced” | |

| number of occurrences of “drug therapy” | |

| both drug and “chemically induced” appear in MeSH | |

| both drug and “adverse effects” appear in MeSH | |

| both drug and “drug therapy” appear in MeSH | |

| both drug and “poisoning” appear in MeSH | |

| both drug and “drug effects” appear in MeSH | |

| both symptom and “chemically induced” appear in MeSH | |

| both symptom and “adverse effects” appear in MeSH | |

| both symptom and “drug therapy” appear in MeSH | |

| both symptom and “poisoning” appear in MeSH | |

| both symptom and “drug effects” appear in MeSH | |

| Textual features | drug in title |

| symptom in title | |

| key in title | |

| drug+symptom in title | |

| symptom+key in title | |

| drug+key in title | |

| drug+symptom+key in title | |

| number of sentences in abstract containing drug | |

| number of sentences in abstract containing symptom | |

| number of sentences in abstract containing key | |

| number of sentences in abstract containing drug+symptom | |

| number of sentences in abstract containing symptom+key | |

| number of sentences in abstract containing drug+key | |

| number of sentences in abstract containing drug+symptom+key | |

Classification algorithm:

Finding articles, which denoted a drug-ADE relationship, can be formulated as a document classification problem. We used logistic regression17 to classify the articles. Feature selection18 used the best predictive features under cross-validation. The classification algorithm uses 2 steps. Step 2 in Figure 1 corresponds to the document classification step where each retrieved article is classified as denoting a drug-neutropenia ADE relation or not. Step 3 in Figure 1 corresponds to the drug-ADE classification step, which uses the results from all the classified documents to determine whether the drug-ADE pair is really an ADE relation. Significant support of an ADE relation is provided if many articles are positively classified, but little support is provided if very few articles are positively classified. Therefore, we used a percentage to compute a ratio of articles that were positively classified over all articles retrieved as a likelihood measure of the actual relation based on the classification of the articles. If the percentage of positively classified articles was high for the drug, based on a threshold which was determined automatically through ROC analysis, this drug was considered to be more likely to cause neutropenia. For example, by searching vinorelbine and neutropenia using a PubMed query, we retrieved 618 publications where 68% of the articles denoted that vinorelbine caused neutropenia. Therefore, it was likely this drug did cause neutropenia. In contrast, when searching meropenem and neutropenia, we retrieved 77 articles, but only 10% were classified as ADE relations, and therefore meropenem-neutropenia was considered unlikely to be an ADE. Therefore, we determined a threshold for the percentage. For some drugs, searching PubMed only returned very few articles (i.e., less than 10); therefore a cutoff value based on the number of retrieved articles was also used to filter out those drugs because there were not enough articles concerning them. We chose the cutoff value of 10.

To evaluate the document classification step (e.g. step 2), we trained and tested the classifier on the 400 samples using 10-fold cross validation experimenting with three sets of features: ontological features only, textual features only, and combined features. This evaluation was used to determine the most predictive feature set. Then the final document classifier was trained on the full data set of 400 samples using the most predictive features.

To evaluate the drug-ADE classification step (e.g. step 3), we used the final document classifier, and classified the articles associated with each drug in the set of 25 drugs, and obtained a percentage of articles positively classified. Area under ROC (AUROC) was used to assess the performance of the drug-ADE classifier.

The overall system was tested on a larger set of different drugs obtained from the SIDER database as potentially causing neutropenia. In SIDER, 210 drugs were listed as causing neutropenia. We removed 30 drugs from the list because they were used in the training set or they had unusual names which could not be identified as drug names, such as ads. This resulted in a set of 180 drugs. A gold standard was created by a physician who determined whether each of the drugs could cause neutropenia. The physician determined that 112 drugs did cause neutropenia and 68 did not.

The overall system was also tested on another adverse event that was different from neutropenia. Myocardial infarction was chosen, and 48 drugs (16 known to cause and 32 known not to cause myocardial infarction) were selected by physicians as the gold standard.

Results

The results of document classification of the 400 samples using 10 fold cross validation are the following. The prediction accuracy was around 0.5 using all 21 ontological features and was 0.73 when selecting 14 features. When using all 14 textual features, the prediction accuracy was 0.75 and none of the smaller feature sets consisting only of textual features performed as well as the full textual feature set. The prediction accuracy using all 35 features from the combined two sets of features was around 0.6 and accuracy using 15 selected features (8 from the ontology and 7 from the text) was 0.78.

Table 2 shows some results of drug-ADE classification for the 25 known drugs. For the drugs known not to cause neutropenia, the percentages generally ranged from 0.0952 to 0.2623, and only one drug filgrastim had a high value of 0.4739. For the drugs known to cause neutropenia, the percentage ranged from 0.5212 to 0.7463 and only one drug mechlorethamine had a low value of 0.4194. The AUROC was 0.99 with 95% CI (0.95 1.00) because there was only one drug misclassified, either filgrastim or mechlorethamine. The sensitivity was 0.89 and specificity was 0.94 using a percentage threshold of 0.45.

Table 2.

Examples from the 25 drugs; the first 3 drugs were known not to cause the neutropenia and the last 3 drugs were known to cause the neutropenia.

| Drug name | # retrieved articles | percentage of articles classified as drug-ADE |

|---|---|---|

| amphotericin | 793 | 0.2623 |

| filgrastim | 614 | 0.4739 |

| meropenem | 77 | 0.1039 |

| 6-mercaptopurine | 94 | 0.5319 |

| mechlorethamine | 31 | 0.4194 |

| vinorelbine | 618 | 0.6828 |

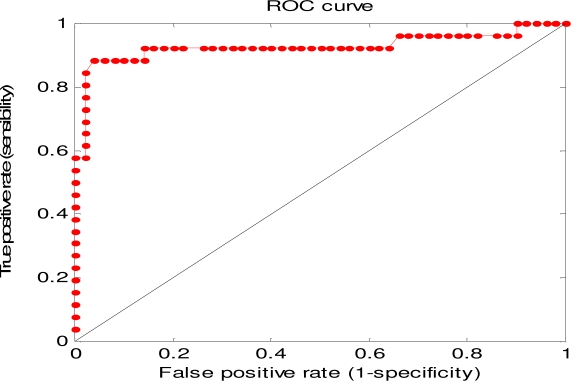

Only 76 drugs from SIDER remained after using a cutoff value of 10 articles. The results of applying the classifier to these 76 drugs are shown in Figure 2. The AUROC was 0.93 with 95% CI (0.86 1.00), the sensitivity was 0.85 and the specificity was 0.98 when using a percentage threshold of 0.45.

Figure 2.

The ROC curve of results for the 76 drugs from SIDER.

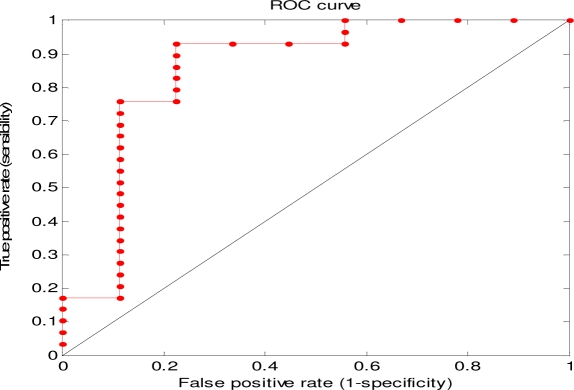

When we applied the classifier to another serious adverse event myocardial infarction, 10 drugs were filtered out because fewer than 10 articles were retrieved for them, and 38 drugs remained. The results are shown in Figure 3. The AUROC was 0.86 with 95% CI (0.74 0.98), the sensitivity was 0.90 and specificity was 0.78 using a percentage threshold of 0.24.

Figure 3.

The ROC curve of results for the 38 drugs associated with myocardial infarction.

Discussion

The drug-ADE detection algorithm was developed based on a machine learning approach using PubMed articles. Empirically, it has been shown that there are no big differences in classification performance for the different classifiers, such as logistic regression, naïve bayes classifier, SVM and other statistical graphical models13–14. The key to the performance of the classifiers were the features. Ontological features used in the algorithm were based on MeSH, which is structured and represents biomedical knowledge corresponding to relevant concepts in the article. The other advantage of using MeSH is that the entire article could have been read by an expert indexer, and the MeSH codes may contain some of the important concepts that were missing from the title and abstract.

The query strategy of searching for a specific drug and ADE pair made the analysis much easier. If we only searched for the drug from PubMed, then too many articles would be retrieved, and the signal of a drug causing an ADE might easily be hidden. The same situation would be true when searching for an ADE only. If the subheading adverse effects appeared many times, it is likely this article was about the ADE, but not necessarily the specific drug we were interested in. But overall this feature did increase the likelihood that the drug we were interested in caused the ADE. If there were several chemicals appearing in the MeSH heading, it was likely this article concerned a drug comparison in a case report or study, which in turn increased the possibility of a drug-ADE relation. Therefore the ontological features contained some information, which improved the prediction.

The method demonstrated its potential for determining a broad range of drug-ADE pairs based on the literature. However, the classifier was successfully applied to 76 drugs from SIDER associated with neutropenia and to another serious adverse event myocardial infarction. The document classifier, which was used in step 2, was learnt based on neutropenia and it was then directly applied to myocardial infarction, which caused the AUROC in Figure 2 to be greater than the AUROC in Figure 3. If we used both samples from the two ADEs to learn the document classifier, the AUROC in Figure 3 might have been better. In future work, we will perform further evaluations using different serious adverse events and different sets of drugs in order to assess whether our approach will generalize well.

The current method will only work for a specific drug, but not for a class of drugs or pro-drugs. For example, azathioprine is a pro-drug which changes into 6-mercaptopurine when ingested into the body. Therefore, side effects reported for azathioprine can be attributed to 6-mercaptopurine, but our method considered them as two different drugs.

The drug filgrastim was misclassified as causing neutropenia because filgrastim was used to decrease infections for patients who received chemotherapy medications, which in turn may decrease the number of neutrophils, and cause neutropenia. The main topic of the articles retrieved from filgrastim concerned the usage of filgrastim with other chemotherapy medications and therefore the extracted features were more similar to the features extracted from the articles describing chemotherapy drugs causing neutropenia. This situation may be very difficult to differentiate. Our method also has limited power to detect the drug-ADE pair from drug combinations, which introduces adverse events caused by drug-drug interactions. Only one drug can be considered in our algorithm, and this method should be generalized to interactions based on use of multiple drugs. Another limitation of this method is that if the drug and adverse event occur in different sentences, the connection might be missed. In the abstract, two or three sentences that are adjacent may together express that the drug caused the ADE, e.g. in the first sentence “docetaxel was used” was stated and “neutropenia was developed after a week” appeared in the second sentence. Currently the textual features were selected by consulting with physicians, but we would try to learn the feature set from the abstract by language properties, such as distance between sentences, and statistical methods, such as topic models, in the following work. Logistic regression only considered a bag of features without dependency; therefore a more sophisticated statistical graphical method should be designed to capture such semantic relationships more accurately. Also the percentage rule in step 3 did not work well for the drugs with only few retrieved articles (e.g. < 10). But the analysis of these drugs could be more important for finding the newer drug-ADEs because they are recent and are usually associated with fewer publications.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed a machine learning method to extract knowledge from PubMed, which determines drug-ADE relationships in order to support pharmacovigilance and decision support. The method uses MeSH headings and subheadings as well as text in the title and abstract. The method was applied to two adverse events neutropenia and myocardial infarction. The results of high drug-ADE prediction accuracy demonstrated the efficacy of the method and its potential to meet our ultimate goal to automatically generate a knowledgebase of serious adverse events to support pharmacovigilance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants 1R01LM010016, 3R01LM010016-01S1, 3R01LM010016-02S1, and 5T15-LM007079-19(HS) from the National Library of Medicine. We thank Feng Liu and Lyudmila Ena for the assistance of searching drug brand names and developing algorithms for detecting abbreviations in the abstracts.

References

- 1.http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2934e/3.html#Jh2934e.3.

- 2.http://www.fda.gov.

- 3.http://www.ema.europa.eu/.

- 4.Evans SJW, Waller PC, Davis S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2001;10(6):483–486. doi: 10.1002/pds.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bate ALM, Edwards IR, Olsson S, et al. A Bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:315–321. doi: 10.1007/s002280050466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindquish MSM, Bate A, et al. A retrospective evaluation of a data mining approach to aid finding new adverse drug reaction signals in the WHO database. Drug Saf. 2000;23(6):533–542. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200023060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DuMouchel W. Bayesian Data Mining in Large Frequency Tables, with an Application to the FDA Spontaneous Reporting System. The American Statistician. 1999;53(3):177–190. [Google Scholar]

- 8.http://www.micromedex.com/.

- 9.Campillos M, Kuhn M, Gavin A-C, Jensen LJ, Bork P. Drug Target Identification Using Side-Effect Similarity. Science. 2008 Jul 11;321(5886):263–266. doi: 10.1126/science.1158140. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/.

- 11.http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/.

- 12.Srinivasan P, Rindflesch T. Exploring text mining from MEDLINE. Proceedings of AMIA Symposium; 2002. pp. 722–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frunza O, Inkpen D. Extraction of disease-treatment semantic relations from biomedical sentences. Proceedings of the 2010 Workshop on Biomedical Natural Language Processing; Uppsala, Sweden. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2010. pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosario B, Hearst MA. Classifying semantic relations in bioscience texts. Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics; Barcelona, Spain. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2004. p. 430. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trifirò G, Pariente A, Coloma PM, et al. Data mining on electronic health record databases for signal detection in pharmacovigilance: which events to monitor? Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2009;18(12):1176–1184. doi: 10.1002/pds.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/rxnorm/.

- 17.Andrew Y, Ng MIJ. On Discriminative vs. Generative Classifiers: A comparison of logistic regression and Naive Bayes. NIPS. 2002:15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell T. Machine Learning. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Merck Manuals: The Merck Manual for Healthcare professionals http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec11/ch132/ch132b.html?qt=neutropenia&alt=sh. Accessed June 24, 2011.

- 20.Andersohn F, Konzen C, Garbe E. Systematic Review: Agranulocytosis Induced by Nonchemotherapy Drugs. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146(9):657–665. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-9-200705010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]