Abstract

As health care systems and providers move towards meaningful use of electronic health records, the once distant vision of collaborative patient-centric, interdisciplinary plans of care, generated and updated across organizations and levels of care, may soon become a reality. Effective care planning is included in the proposed Stages 2–3 Meaningful Use quality measures. To facilitate interoperability, standardization of plan of care messaging, content, information and terminology models are needed. This degree of standardization requires local and national coordination. The purpose of this paper is to review some existing standards that may be leveraged to support development of interdisciplinary patient-centric plans of care. Standards are then applied to a use case to demonstrate one method for achieving patient-centric and interoperable interdisciplinary plan of care documentation. Our pilot work suggests that existing standards provide a foundation for adoption and implementation of patient-centric plans of care that are consistent with federal requirements.

Keywords: plan of care, electronic health record, meaningful use, terminology standards

Introduction

The goal of the interdisciplinary plan of care is to support continuity, quality, and safe patient-centric care. Individualized patient care is often not visible in the medical record1 and discrepancies exist between information found in the plan of care in the patient record and verbal reports from providers and patients about their perception of the plan.2 Poorly designed electronic systems can exacerbate these problems. While interdisciplinary plans of care are required by regulatory agencies for accreditation and reimbursement,3 the majority of research to date has focused on development of plan of care applications for use by a single discipline, e.g., nursing.2,4,5 This silo approach is unlikely to meet the intended effect of the plan of care, which is to bridge communication between care team members and reflect an interdisciplinary approach to problem identification, goal setting, intervention coordination and assignment, intervention termination criteria definition, and documentation of progress towards meeting the plan’s goals.

Background and Significance

Collaboration of team members on the plan of care across disciplines is associated with improved patient outcomes6,7 and an integrated approach to care is especially critical for supporting self-management of patients with a chronic illness.8,9 Patient involvement in goal setting and ongoing status updates is also key to successful disease self-management because patients actively engaged in the management of their own chronic illness are less likely to be rehospitalized after an acute exacerbation.10 The challenge is to build an informatics infrastructure that supports integration of plan of care documentation into workflows that exist across the continuum and to facilitate input by all team members (including patients). A patient-centric approach to care planning is needed; an approach that includes patient involvement in the generation and update of the plan of care and the ongoing patient self-management plan is essential. Proposed Stages 2–3 Meaningful Use measures will assess the presence of a completed and comprehensive longitudinal plan of care that includes the patient self-management plan.11 Existing systems and workflows related to generation and update of plans of care in use at many organizations would likely not meet Meaningful Use criteria as they are typically generated by a single discipline (nursing) and patient involvement is variable. The purpose of this paper is to report on some of the existing standards that may be leveraged to begin to build interdisciplinary, comprehensive patient-centric plans of care.

To facilitate interoperability, standardization of plan of care messaging, content, information and terminology models are needed. In 2010, IHE (Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise) published the Patient Plan of Care (PPOC) profile to facilitate electronic exchange of longitudinal individualized patient care data between and among HIT systems.12

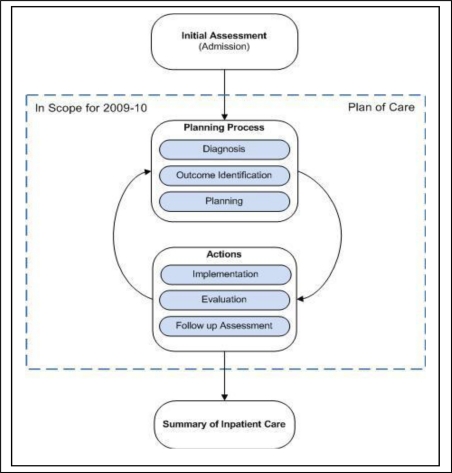

The IHE PPOC proposes use of HL7 CDA release 2.0 and ASTM/HL713 Continuity of Care Document14 standards for messaging. The scope of the PPOC profile is limited to nursing documentation and it leverages the American Nurses Association (ANA) nursing process15 as the framework for the PPOC information model. The IHE PPOC demonstrates the exchange of PPOC information based on concepts that relate to the nursing process framework including diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

IHE Components of the PPOC Process

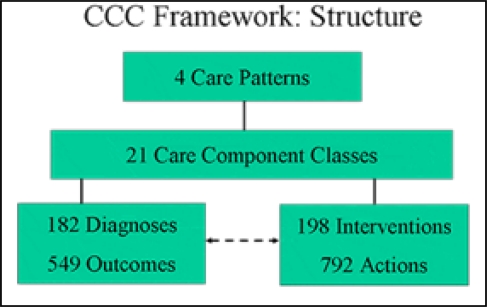

The content and terminology standards proposed in the IHE PPOC model are the Clinical Care Classification (CCC) System.16 CCC was selected for this purpose because its framework is based on the six steps of the nursing process and is therefore consistent with the proposed IHE information model. The current CCC System Version 2.0 consists of 182 Nursing Diagnoses and 546 Nursing Outcomes (one diagnosis with one of 3 Expected / Actual Outcomes: Improved, Stabilized, or Deteriorated) and 792 Nursing Interventions (198 Core Interventions with one of 4 Action Types: Assess, Perform, Teach, or Manage). The two terminologies are integrated and classified by 21 Care Components to form one system.16

The CCC System consists of a four level framework which allows data to be aggregated upward as well as parsed downward to atomic level concepts (see Figure 2). The CCC System structure supports reporting of the “essence of care” including high level patient outcomes17 and determining nursing practice patterns for costing and third party reimbursement of nursing care.18

Figure 2:

CCC Framework Structure

The first level consists of the four healthcare patterns -- physiological, psychological, functional, and health behavioral. The next level consists of 21 Care Components which represent a cluster of data elements that depict the four healthcare patterns and are used to classify the two terminologies. The Care Components represent a holistic approach to patient care and provide the framework to facilitate the electronic processing of nursing plans of care following the six standards/steps of the nursing process. The next level consists of the actual two terminologies: 182 diagnoses and 198 core interventions; and the final level, is used to code either the 3 expected or actual outcomes to make 546 diagnoses or the four action types for the 792 intervention actions.

While the scope of the IHE PPOC profile is focused on nursing documentation, it could potentially support interdisciplinary PPOC documentation. The proposed IHE PPOC messaging standards are domain agnostic and the proposed information model is likely to be relevant across domains of practice. The nursing process is based on the scientific method19 which is a framework common to all disciplines. Strategies are needed to address potential gaps in content and controlled terms to encode interventions with varying levels of granularity. The use of a single terminology (e.g., CCC) may not fully support generation and update of interdisciplinary, patient-centric, plans of care without loss of context. Moreover, the domains of nursing, medicine and the health professions are represented by multiple, overlapping nursing and clinical terminologies such as International Classification of Nursing Practice (ICNP) and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT). Integration of PPOC concepts from across repositories would require interoperability between the various terminologies used to encode clinical repositories and PPOC data. In addition, to fully meet the proposed Stage 2–3 Meaningful Use criteria related to automated reporting on the presence and update to the PPOC and self-management plan, it will likely be necessary to encode very granular intervention concepts that do not exist in the CCC System. Therefore, a mechanism is needed to link fine grained concepts found in clinical terminologies such as SNOMED CT with the more coarsely granular concepts contained in CCC. A strategy employed previously for using the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS®) to automatically map finely granular adverse event concepts found in SNOMED CT with MedDRA concepts for aggregation of cases and reporting20 may be applicable to mapping finely grained PPOC concepts from diverse clinical terminologies to CCC. The UMLS® includes over 150 terminologies in a common format. The UMLS® is an integration tool bridging the gap between terminologies used across healthcare domains and the UMLS® integrates many clinical terminologies including SNOMED CT.21 SNOMED CT is a comprehensive clinical terminology that includes many of the ANA approved nursing terminologies and other clinical terminologies. SNOMED CT is owned, maintained, and distributed by the International Health Terminology Standards Development Organization.22

Research Methods

The following questions are addressed in the sections that follow.

What is the interoperability of CCC with SNOMED CT to support data consistency of intervention concepts for use in interdisciplinary PPOC reporting?

How might the following content, messaging information and terminology standards be leveraged to support interdisciplinary POC documentation: IHE PPOC (information model), ASTM/HL713 Continuity of Care Document (messaging), CCC (content/terminology) and SNOMED CT (terminology).

The complete set of 198 CCC core interventions (e.g. without action types) were used as a test case to explore the interoperability of CCC with SNOMED CT using the UMLS® version 2010AB. The UMLS®Metathesaurus

Browser was used first to associate the SNOMED CT concepts with CCC concepts by entering the CCC intervention concept into the UMLS “term search” box and selecting “HHC” as the source (CCC is listed in UMLS under former name, Home Health Care Classification or HHC). In the UMLS “Report View” section of the browser under “Atoms” we then identified the SNOMED CT preferred term (if available). To investigate the use of the hierarchical structures of SNOMED CT for harvesting fine grained concepts to support detailed interdisciplinary PPOC reporting, the Child relations of each SNOMED PT match were harvested and entered into a spreadsheet. Harvested concepts were then applied to a PPOC use case for pneumonia.

Results

Using UMLS as the reference standard, 88.4% (n=175) of CCC core intervention concepts are interoperable with SNOMED CT. For each SNOMED CT term identified as a match with the core CCC concept, the list of child concepts were identified in the UMLS®. Among the SNOMED CT terms mapped to CCC core concepts, 46% (n=91) have one or more child concepts. When present, the number of child SNOMED CT concepts ranged from 1–155. A total of 745 SNOMED CT concepts were found in the child terms with direct mappings to the core CCC concepts. A total of additional 9,024 SNOMED CT concepts can be linked to the 198 CCC core concepts through the child concepts of the SNOMED CT terms to which CCC concepts are mapped directly.

Pneumonia PPOC use case:

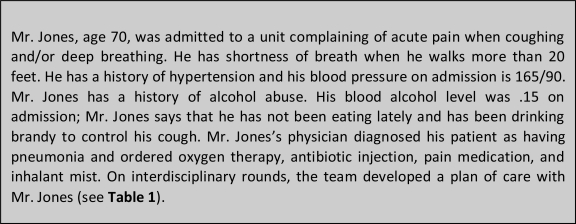

The following use case is employed to demonstrate how a set of existing messaging information and terminology standards are leveraged to support interdisciplinary POC documentation. The case study is included in Figure 3 and the associated interdisciplinary PPOC is included in Table 1.

Figure 3:

Pneumonia PPOC case study

Table 1:

Interdisciplinary PPOC for patient admitted with pneumonia (see case study, Figure 3).

| Medical Disagnoses/SNOMED CODE | CCC Care Components/Diagnosis | CCC Goals | Planned Interdisciplinary Interventions | CCC Action Types/lnterventions | SNOMED CT Detailed Interventions | Actual Outcomes/Goals Met | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia: 233604007 | Respiratory/Breathing Pattern Impairment: L26.2 | Stabilize Breathing Pattern Impairment: L26.2.2 | Administer oxygen therapy (RT) Deep breaths performed with a positive expiratory pressure blow-bottle device (RT) Incentive Spirometer (RN) Postural drainage (RT) Give dose of mist inhalant-qid (RT) |

Perform/Oxygen Therapy Care: L35.0.2 Perform/Breathing Exercises: L36.1.2 Perform/Chest Physiotherapy: L36.2.2 Peform–Medication Treatment - H24.4.2 |

Humidified oxygen therapy: 304577004 Breathing exercise, blow bottle: 11310004 Respiratory expansion exercises: Incentive spirometry: 229301009 Respiratory drainage techniques: 306765008 Mist inhalation therapy: 229303007 |

Breathing Pattern Impairment Stabilized - L26.2.2 | Evidence = Able to walk more than 20 |

| Sensory/Acute Pain: Q45.1 | Improve Acute Pain: Q45.1.1 | Determine pain intensity (RN) Instruct how to splint for coughing (RN) Give pain medication-prn |

Assess–Acute Pain Control - Q47.1.1 Teach–Acute Pain Control - Q47.1.3 Perform—Medication Treatment - |

NA (no detailed Intervention required) | Acute Pain Improved - Q45.1.1 | Pain level: 0 | |

| Medication/Medication Risk: H21 | Stabilize Medication Risk: H21.0.2 | Perform medication reconciliation (MD/RN) | Perform–Medication Treatment-H24.4.2 | Medication Reconciliation: 430193006 | Medication Risk Improved: H21.0.1 | Inpatient medciations reconciled with outpatient | |

| Nutrition/Nutrition Alteration: J24 | Improve Nutrition Alteration: J24.0.1 | Provide nutrition consult. Provide education re: weight gain |

Refer: Nutrition Care: J29.0.4 Perform Weight Control: J67.0.2 |

Weight gain regimen: 388978005 | Nutrition Alteration Improved: K24.0.1 | Weight gain 6 lbs | |

| Physical Regulation/Hyperthermia:K25.2 | Improve Hyperthermia: K25.2.1 | Give IM antibiotic injection-qid | Perform–Injection Administration - H23.0.2 | Hyperthermia Improved - K25.2J | Hyperthermia Improved: K.25.2.1 | Afebrile | |

| Hypertension: 38341003 | Physical Regulation/Blood Pressure Alteration: C06.1 | Improve Blood pressure: C06.1.1 | Vital signs q4 hours Patient report blood pressure after discharge to Primary care MD (Patient) |

Perform/Blood Pressure: K33.1.2 Teach/BIood Pressure: K33.1.3 |

Blood pressure recorded by patient at home: 413153004 | Blood Pressure Alteration Improved: | BP: 130/80 at DC Patient submitted BP after DC: 135/78 |

| Activity/Activity Intolerance: A01.1 | Improve Activity Intolerance: A01.1.1 | Teach Energy Conservation techniques Ambulation Therapy (PT) |

Teach/Energy Conservation: A01.2.3 Perform/Ambulation Therapy: A03.1.2 |

228632007|energy conservation education| 370871008|ambulation therapy| |

Activity Intolerance Improved: A01.1.1 | Ambulate 50 feet without SOB | |

| Safety/Alcohol Abuse: N58.2 | Stabilize Alcohol Abuse: N58.2.2 | Screen for Alcohol dependence (RN) Provide Alcohol dependence counseling (Substance about |

Assess/Alchol Abuse Control: N40.2.1 Perform/Alcohol Abuse Control: N40.2.2 |

Cage questionnaire: 273347006 Alcohol consumption counseling: 413473000 |

Alcohol Abuse Stabilized: N58.2.2 | Patient agrees to attend AA after discharge. |

The IHE Patient Plan of Care (PPOC) profile leverages the CCD as the messaging standard for PPOC and the ANA nursing process as the framework for the information model. The Continuity of Care Document (CCD) is a messaging standard that provides an electronic summary of a patient’s clinical information without loss of context.1 At the time of discharge from the acute care hospital, an electronic summary of Mr. Jone’s inpatient care will be required by the home care agency that follows him. In addition, a copy will be given to Mr. Jones in accordance with his format preference (e.g., CCD can be exported as a paper-based (pdf) or in electronic (XML) format). The CCD includes data that define pending orders, interventions, encounters, services, procedures goals and clinical reminders—all necessary elements of the PPOC. To evaluate the utility of CCC and SNOMED CT as content and terminology standards, an interdisciplinary PPOC was developed related to the admission of Mr. Jones to an acute medical unit with the diagnoses of pneumonia.

Discussion

In this study, SNOMED CT concepts were mapped to CCC to translate them into CCC terms to support high level reporting and the PPOC generation and update process. As done previously,20 the hierarchy of SNOMED CT is proposed for aggregation purposes to ensure that the appropriate level of granularity is available to support both detailed clinical documentation and reporting. The overall mapping of CCC to SNOMED CT is quite good (88.4%). This is not surprising, given that CCC has been incorporated into SNOMED CT. While exact matches do not exist, for 11.6% of CCC intervention concepts in UMLS, the lack of a match is due to differences in the terminology models, and the lack of an exact match does not preclude interoperability. The CCC terminology model requires that one of the following action types is associated with each CCC intervention: assess, perform, educate or manage. For CCC intervention concepts without an exact match in SNOMED CT, related SNOMED CT concepts exist that include the action type and intervention in a single concept. As a result, there is not an exact match in UMLS, but matches do generally exist in SNOMED CT for precoordinated CCC concepts. For example, there is no exact match in UMLS for the CCC concept “transfer care”. However, there is a SNOMED CT concept, “patient transfer (C0030704)” that according to its definition (Performance of the steps necessary to transfer a patient between locations of care delivery), it is an exact match with the CCC precoordinated concept, “perform patient transfer”.

The additional linkages from more coarse CCC concepts to the fine grained SNOMED CT concepts (9,024 in total) provides a mechanism for capturing clinical detail at the bedside and then reused at the appropriate level of granularity. The structure of the IHE PPOC profile encoded with CCC concepts provides a mechanism for generating and updating plans of care that will provide linkages between problem-specific interventions executed by the interdisciplinary team and associated patient outcomes. This type of framework will support building evidence from practice as the proposed IHE information model links assessment-diagnosis-planning-evaluation.

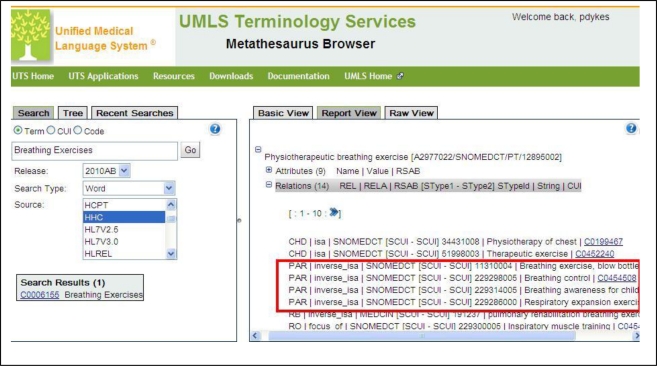

The PPOC use case in Table 1 is an example of how the IHE plan of care profile (Figure 1) encoded with CCC and SNOMED CT concepts could potentially support generation and update of an interdisciplinary PPOC. Based on the initial admission assessment/history and physical exam, diagnoses/patient problems are identified. In Table 1, both medical diagnoses (encoded in SNOMED CT) and interdisciplinary diagnoses (encoded in CCC) are included. The CCC framework within the IHE PPOC profile provides a mechanism for setting high-level, yet measurable goals that align with both medical and interdisciplinary diagnoses (e.g., Stabilize Breathing Pattern Impairment) and define the interdisciplinary interventions that are prescribed to meet those goals. Where additional specificity is needed to represent detailed, discipline-specific care, the hierarchy within SNOMED CT is leveraged. Fine grained SNOMED CT intervention concepts that map directly to the coarser grained CCC intervention concepts are used. For example, both nursing and respiratory therapy are providing respiratory interventions. The coarse grained CCC interventions are sufficient for representing some of the nursing interventions (e.g., teach breathing exercises), but more detailed SNOMED CT concepts are needed to represent more specific interventions and the work of respiratory therapy to avoid losing context (e.g., breathing exercises using a blow bottle) see Figure 4. The CCC outcome concepts provide a means to record patient progress toward hospitalization goals and goal resolution—important components of the plan of care that must be communicated to the next level of care and the patient at discharge using the CCD.

Figure 4:

UMLS Methathesaurus Browser. Term search for CCC Intervention Concept “Breathing Exercises” maps to SNOMED CT term “Physiotherapeutic breathing exercises” (PBE). Of the 14 existing relations, 4 are child concepts that are leveraged to prevent loss of context when documenting the respiratory therapy intervention “Breathing exercises, blow bottle”.

There are several limitations associated with this work. Our work focused on two terminology standards; CCC and SNOMED CT. Additional work is needed to evaluate other standards such as ICNP and LOINC, that would likely improve interoperability of PPOC. Additional work is needed to better understand how additional standards might be leveraged to improve interoperability without loss of clinical context. In addition, strategies for patient involvement in the generation and update process are needed. This may require modification of existing terminologies or development of a consumer-centric terminology that represents the PPOC and self-management concepts needed to facilitate sharing of patient-generated data.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to review a set of existing standards that may be leveraged to support development of interdisciplinary patient-centric plans of care. Standards were applied to a use case to demonstrate one method for achieving patient-centric and interoperable interdisciplinary plan of care documentation. Our pilot work suggests that existing standards provide a foundation for adoption and implementation of patient-centric plans of care that are consistent with federal requirements. Additional work is needed to evaluate the role of other terminology standards in achieving longitudinal interoperable patient centric plans of care and in understanding the requirements needed to support patient involvement in the generation and update process.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Keenan G, Yakel E, Tschannen D, Mandeville M. Patient Safety and Quality An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Documentation and the Nurse Care Planning Process. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehrenberg A, Ehnfors M. The accuracy of patient records in Swedish nursing homes: congruence of record content and nurses’ and patients’ descriptions. Scand J Caring Sci. 2001;15(4):303–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2001.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.TJC The Joint Commission E-dition. Hospital. [July 1, 2010. Accessed November 30, 2010.

- 4.Darmer MR, Ankersen L, Nielsen BG, Landberger G, Lippert E, Egerod I. Nursing documentation audit--the effect of a VIPS implementation programme in Denmark. J Clin Nurs. 2006 May;15(5):525–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellefield ME. Interdisciplinary care planning and the written care plan in nursing homes: a critical review. Gerontologist. 2006 Feb;46(1):128–133. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, et al. Association between nurse-physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1999 Sep;27(9):1991–1998. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzocco K, Petitti DB, Fong KT, et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg. 2009 May;197(5):678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grady KL, Dracup K, Kennedy G, et al. Team management of patients with heart failure: A statement for healthcare professionals from The Cardiovascular Nursing Council of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000 Nov 7;102(19):2443–2456. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.19.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powell LH, Calvin JE, Jr, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. The Heart Failure Adherence and Retention Trial (HART): design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2008 Sep;156(3):452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jovicic A, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Straus SE. Effects of self-management intervention on health outcomes of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006;6:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-6-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quality Measure Workgroup Recommendations for Stage 2 and Stage 3 Meaningful Use. Washington, DC: Mar 1, 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boone K. IHE Patient Care Coordination (PCC) Technical Framework Supplement Patient Plan of Care (PPOC) Trial Implementation. Aug 30, 2010. http://www.ihe.net/Technical_Framework/upload/IHE_PCC_Suppl_PPOC_Rev1-2_TI_2010-08-30.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2011.

- 13.HL7 Clinical Document Architecture Release 2.0. http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/cda.cfm. Accessed March 10, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.HL7 Product Brief - CCD - Continuity of Care Document. http://wiki.hl7.org/index.php?title=Product_CCD.

- 15.ANA . Nursing: Scope & Standards of Practice. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical Care Classification System. 2011. http://www.sabacare.com/. Accessed March 15, 2011.

- 17.Moss J, Damrongsak M, Gallichio K. Representing Critical Care Data Using the Clinical Care Classification. 2005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moss J, Saba V. Comput Inform Nurs. Nov 16, Costing Nursing Care: Using the Clinical Care Classification System to Value Nursing Intervention in an Acute-Care Setting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels R. Nursing fundamentals: caring & clinical decision making. Clifton Park, NY: Thompson Learning, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodenreider O. Using SNOMED CT in combination with MedDRA for reporting signal detection and adverse drug reactions reporting. AMIA Annu Symp Proc; 2009. pp. 45–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NLM Fact Sheet: Unified Medical Language System. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/umls.html. Accessed March 11, 2011.

- 22.IHTSDO SNOMED CT. http://www.ihtsdo.org/snomed-ct/. Accessed March 15, 2011.