Abstract

Two-component systems are an evolutionarily ancient means for signal transduction. These systems are comprised of a number of distinct elements, namely histidine kinases, response regulators, and in the case of multi-step phosphorelays, histidine-containing phosphotransfer proteins (HPts). Arabidopsis makes use of a two-component signaling system to mediate the response to the plant hormone cytokinin. Two-component signaling elements have also been implicated in plant responses to ethylene, abiotic stresses, and red light, and in regulating various aspects of plant growth and development. Here we present an overview of the two-component signaling elements found in Arabidopsis, including functional and phylogenetic information on both bona-fide and divergent elements.

INTRODUCTION

Protein phosphorylation is a key mechanism for regulating signal transduction pathways in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In eukaryotes, regulatory phosphorylation predominantly occurs at serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues (Hunter, 1995; Hunter and Plowman, 1997; Plowman et al., 1999). In contrast, many signal transduction pathways in bacteria employ a so-called “two-component system” that relies upon phosphorylation of histidine and aspartic-acid residues (Mizuno, 1997). Plants also make use of two-component systems and these perform important roles in growth and development (Schaller, 2000; Mizuno, 2005; To and Kieber, 2008).

Two-component systems confer upon bacteria the ability to sense and respond to environmental stimuli and are involved in such diverse processes as chemotaxis, osmotic sensing, oxygen sensing, and host recognition (Parkinson, 1993; Stock et al., 2000; Baker et al., 2006). The simplest form of a two-component system employs a receptor with histidine-kinase activity and a response regulator (Figure 1). The receptor is located in the plasma membrane of the bacterium. In response to an environmental stimulus, the histidine kinase autophosphorylates a conserved histidine residue. This phosphate is then transferred to a conserved aspartic acid residue within the receiver domain of the response regulator. Phosphorylation of the response regulator modulates its ability to mediate downstream signaling. In bacteria, many of the response regulators are transcription factors. Thus, two proteins create a signaling circuit, capable of converting an external stimulus into a change in transcription. There are permutations on the two-component system. Of particular relevance to the plant two-component systems are multi-step phosphorelays (Figure 1) (Swanson et al., 1994; Appleby et al., 1996). These make use of a “hybrid” kinase that contains both histidine kinase and receiver domains in one protein, a histidine-containing phosphotransfer (HPt) protein, and a separate response regulator (Appleby et al., 1996). In these multi-step phosphorelays, the phosphate is transferred from amino acid to amino acid in sequence His → Asp → His → Asp.

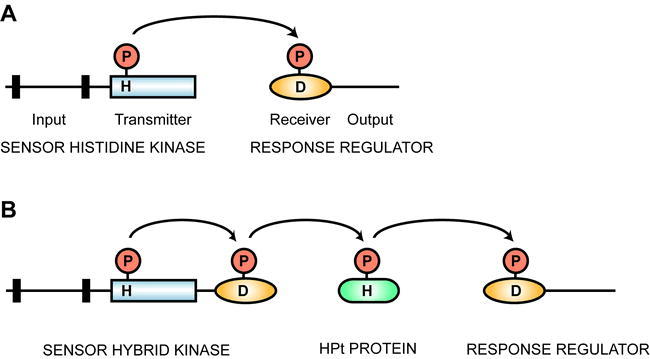

Figure 1.

Histidyl-Aspartyl Phosphorelay.

Histidine kinase domains are indicated by rectangles, receiver domains by ovals, HPt proteins by rounded rectangles, and transmembrane domains by black bars. Sites of phosphorylation upon histidine (H) and aspartic acid (D) residues are indicated. Terminology is based on that of Parkinson (1993).

(A) Simple two-component system that employs a histidine kinase and a response regulator.

(B) Multi-step phosphorelay that employs a hybrid histidine kinase with both histidine kinase and receiver domains, a histidine-containing phosphotransfer protein (HPt), and a response regulator.

Although originally identified in bacteria, two-component signaling elements have also been identified in fungi, slime molds, and plants (Swanson et al., 1994; Loomis et al., 1997; Schaller, 2000; Mizuno, 2005). Interestingly, the canonical histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelay is apparently not found in animals. Analysis using the SMART protein-domain search interface (http://SMART.embl-heidelberg.de) (Schultz et al., 2000) indicates that bona-fide two-component signaling elements are lacking from the genome sequences of Homo sapiens, Drosophila melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans.

In Arabidopsis, proteins with significant sequence similarities to all elements of the two-component system have been identified, including histidine kinases, response regulators, and HPt proteins (Figure 2) (Schaller, 2000; Mizuno, 2005). Phosphorylation activity has been confirmed for at least one example in each case (Gamble et al., 1998; Imamura et al., 1998; Miyata et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 1998; Imamura et al., 1999). In recent years, multiple experimental approaches have demonstrated the action of a histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelay in mediating cytokinin signal transduction (Hwang and Sheen, 2001; Higuchi et al., 2004; Nishimura et al., 2004; Mason et al., 2005; Hutchison et al., 2006; Riefler et al., 2006; Yokoyama et al., 2007).

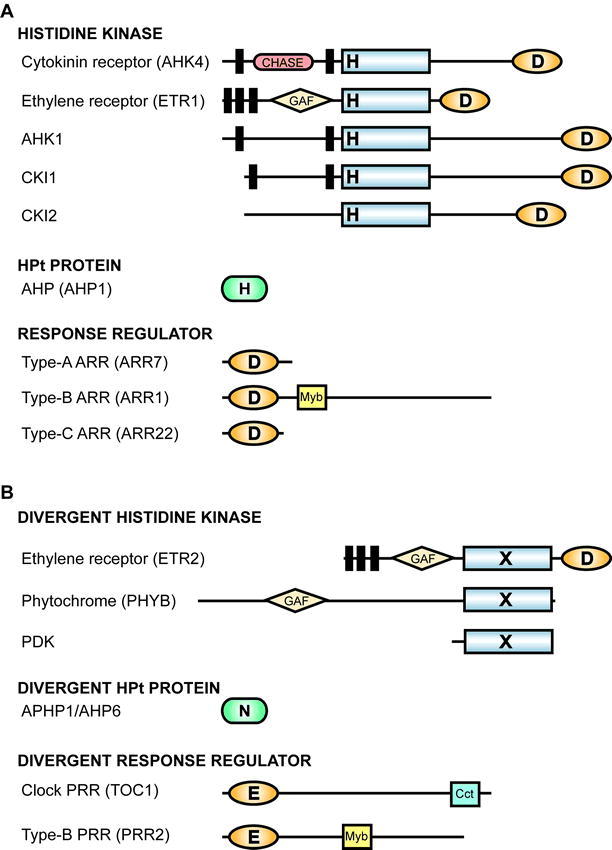

Figure 2.

Representative Domain Structures of Arabidopsis Two-Component Signaling Elements.

Histidine kinase domains are indicated by rectangles, receiver domains by ovals, HPt proteins by rounded rectangles, and transmembrane domains by black bars. Additional domains are as indicated and are described in the text.

(A) Bona-fide signaling elements likely to participate in phosphorelays. Sites of phosphorylation upon histidine (H) and aspartic acid (D) residues are indicated.

(B) Divergent signaling elements from Arabidopsis that lack residues normally associated with participation in a two-component phosphorelay. An X in a histidine-kinase-like domain indicates that it lacks multiple residues implicated in histidine kinase activity. The divergent HPt (APHP1) contains an Asn (N) substitution for the His that normally gets phosphorylated. The divergent response regulators typically contain a Glu (E) substitution for the Asp that normally gets phosphorylated.

Arabidopsis also contains divergent two-component-like elements that are unlikely to function in histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelays (e.g. phytochromes and pseudo-response regulators) as they are missing one or more key amino-acid residues involved in a phosphorelay (Figure 2) (Makino et al., 2000; Schaller, 2000). Plants, like animals, contain pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; this enzyme is related to histidine kinases but has an altered specificity such that it now phosphorylates serine residues (Popov et al., 1993). Thus, there is evidence from eukaryotes that two-component signaling elements have evolved to fill new functions that no longer rely upon phosphorylation of histidine and aspartic acid residues.

HISTIDINE KINASES

Analysis of the Arabidopsis genome supports the existence of eight histidine kinases that contain all the conserved residues required for enzymatic activity (Table 1, Figures 2 and 3), as well as additional diverged histidine-kinase like proteins that lack residues essential to histidine kinase activity. Some of the functional histidine-kinases have been identified as receptors for the plant hormones cytokinin (AHK2, AHK3, and AHK4) and ethylene (ETR1 and ERS1), but the ligands for the other three bona-fide histidine kinases (AHK1, CKI1, and CKI2) have yet to be determined.

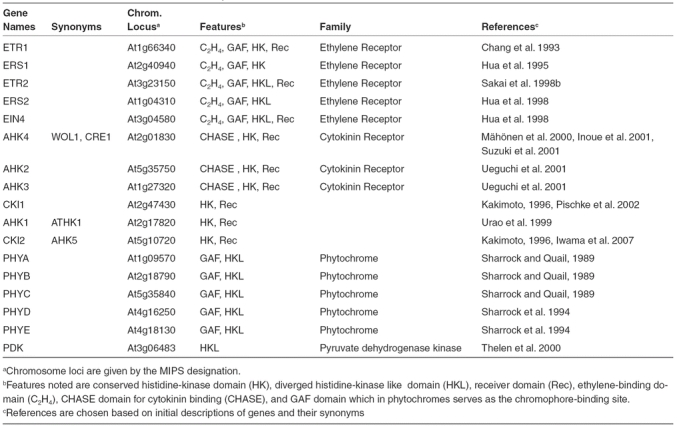

Table 1.

Histidine Kinase-like Proteins of Arabidopsis

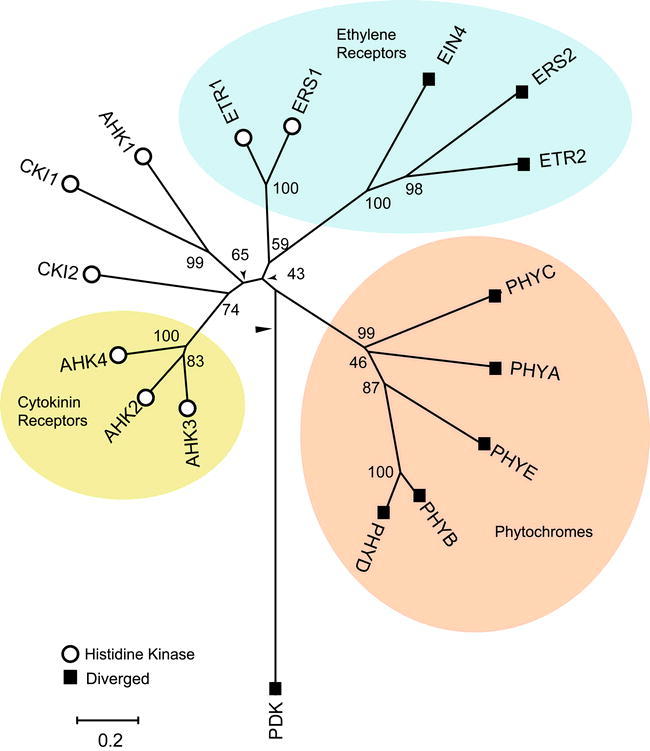

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic Relationship of Histidine Kinases.

Sequences containing conserved histidine-kinase domains (open circles) and diverged histidine kinase domains (filled squares) were identified in Arabidopsis. An unrooted bootstrapped tree is shown based on amino-acid alignment of the histidine-kinase domain sequences. The histidine kinase domain was defined as the sequence extending from the phospho-acceptor domain through the ATPase domain.

Cytokinin Receptor Family

The cytokinin receptor family is composed of three histidine kinases: AHK2, AHK3, and AHK4 (also called WOL1 or CRE1). Initial evidence that this family functions in cytokinin perception came from the study of AHK4 transgenically expressed in bacteria and yeast, where it was shown that AHK4 could bind cytokinins and that ligand-binding stimulated the receptor's ability to signal through a phosphorelay (Inoue et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2001; Ueguchi et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2001). All three receptors contain transmembrane domains, are thought to be localized to the plasma membrane, and contain a CHASE (<u>c</u>yclases/<u>h</u>istidine kinases <u>a</u>ssociated <u>s</u>ensing <u>e</u>xtracellular) domain in their predicted extracellular portion that functions in cytokinin binding (Anantharaman and Aravind, 2001; Heyl et al., 2007). The isolation and characterization of T-DNA insertion mutations has demonstrated roles for the cytokinin receptors in diverse cytokinin-regulated processes including cell division, vascular differentiation, leaf senescence, seed size, and stress responses (Higuchi et al., 2004; Nishimura et al., 2004; Riefler et al., 2006; Tran et al., 2007).

Ethylene Receptor Family

The ethylene receptor family of Arabidopsis (ETR1, ERS1, ETR2, ERS2, and EIN4) also contains proteins with histidine kinase domains (Chang et al., 1993; Hua et al., 1995; Hua et al., 1998; Sakai et al., 1998). ETR1 and ERS1 have been demonstrated to bind ethylene when transgenically expressed in yeast (Schaller and Bleecker, 1995; Rodriguez et al., 1999; Hall et al., 2000) and both contain functional histidine kinase domains (Gamble et al., 1998; Moussatche and Klee, 2004). Although histidine-kinase activity has been implicated in subtle modulations of the ethylene response, no major role has yet been identified in ethylene signal transduction (Wang et al., 2003; Binder et al., 2004; Qu and Schaller, 2004). Mutational analysis indicates that, rather than relying on a histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelay, ethylene signal transduction incorporates the Raf-like kinase CTR1, the membrane-bound Nramp-like protein EIN2, and the EIN3 family of transcription factors (Chen et al., 2005). Histidine kinase activity of the ethylene receptors could play a direct but lesser role in ethylene signal transduction. Alternatively, histidine kinase activity could allow for cross-talk between ethylene perception and other two-component signaling pathways such as cytokinin signal transduction.

The ethylene-receptor family also includes three members (ETR2, ERS2, and EIN4) that contain divergent histidine-kinase domains (Bleecker, 1999; Schaller, 2000). Thus, one protein family of related function contains both bona-fide and divergent histidine kinases. Based on in-vitro phosphorylation assays, ETR2, ERS2, and EIN4 are now thought to function as ser/thr kinases (Moussatche and Klee, 2004). In the same study ERS1 was found to phosphorylate serine in addition to histidine, suggesting that it might be bi-functional.

CKI1

CKI1 was initially identified in a mutant screen where it was found that its ectopic expression results in cytokinin-independent greening and shoot induction in callus cultures (Kakimoto, 1996). However CKI1 is not closely related to the cytokinin-receptor family and lacks the CHASE domain involved in cytokinin binding. Thus, the cytokinin-related phenotype resulting from CKI over-expression may arise due to non-physiological cross-talk with the cytokinin-signaling pathway. Analysis of loss-of-function mutations has clarified the role of CKI1 in plant growth and development, although a regulatory ligand for this putative receptor has not been identified. The homozygous cki1 mutation is lethal and examination of the mutant indicates that CKI1 is required for megagametogenesis, consistent with expression data that indicate CKI1 is expressed in developing ovules (Pischke et al., 2002; Hejatko et al., 2003).

CKI2

CKI2, like CKI1, can induce cytokinin responses when ectopically expressed (Kakimoto, 1996), but is also not thought to be directly involved in cytokinin signaling. CKI2 shows strong expression in the root and weaker expression in flowers (Iwami et al., 2007). Loss-of-function mutations in CKI2 exert a subtle phenotype in which root elongation is more sensitive to growth inhibition in response to ethylene, suggesting possible cross-talk with the ethylene receptors (Iwami et al., 2007).

AHK1

AHK1 was initially proposed to function as a plant osmosensor based on its ability to complement function of the yeast osmosensor SLN1, a histidine kinase that regulates the HOG1 MAP-kinase pathway for osmosensing in yeast (Urao et al., 1999). However it was subsequently found that other histidine kinases of Arabidopsis, including the cytokinin receptors, can complement yeast SLN1 mutations, indicating that this assay is not necessarily diagnostic of plant function (Reiser et al., 2003; Tran et al., 2007). Rather, genetic analysis indicates that AHK1 modulates plant growth and stress responses based on the finding that an ahk1,ahk2,ahk3 triple mutant (i.e. a combination of ahk1 with two cytokinin receptor mutations) is reduced in size compared to the ahk2,ahk3 double mutant (Tran et al., 2007). AHK1 is induced by dehydration and acts as a positive regulator of drought and salt stress responses, in contrast to the cytokinin receptors which are also induced by dehydration but act as negative regulators of these responses (Tran et al., 2007).

Phytochrome Family

The phytochromes, which act as red light receptors (Sharrock and Quail, 1989; Clack et al., 1994; Rockwell et al., 2006), are divergent histidine kinases that possess ser/thr kinase activity rather than histidine kinase activity (Yeh and Lagarias, 1998).

Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase

Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase retains the most highly conserved residues found in histidine kinases, but has nevertheless diverged significantly in other residues, resulting in an ability to phosphorylate its substrate, pyruvate dehydrogenase, at a serine residue (Thelen et al., 2000).

HISTIDINE-CONTAINING PHOSPHOTRANSFER PROTEINS

Histidine-containing phosphotransfer (HPt) proteins function in multi-step phosphorelays, acting as signaling intermediates between hybrid histidine kinase and response regulators (Figure 1). The Arabidopsis genome encodes five HPt proteins (AHP1 through 5) that contain the conserved residues required for activity, as well as one pseudo-HPt (APHP1/AHP6) that lacks the histidine phosphorylation site (Table 2, Figures 2 and 4) (Miyata et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2000). The HPt proteins have been shown capable of participating in a phosphorelay with Arabidopsis response regulators (Suzuki et al., 1998). In addition, two-hybrid analysis has demonstrated their ability to interact with both hybrid histidine kinases and response regulators (Imamura et al., 1999; Urao et al., 2000; Tanaka et al., 2004; Dortay et al., 2007), consistent with an ability to function in a multi-step phosphorelay.

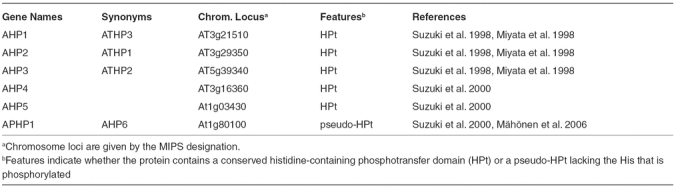

Table 2.

HPt Proteins of Arabidopsis

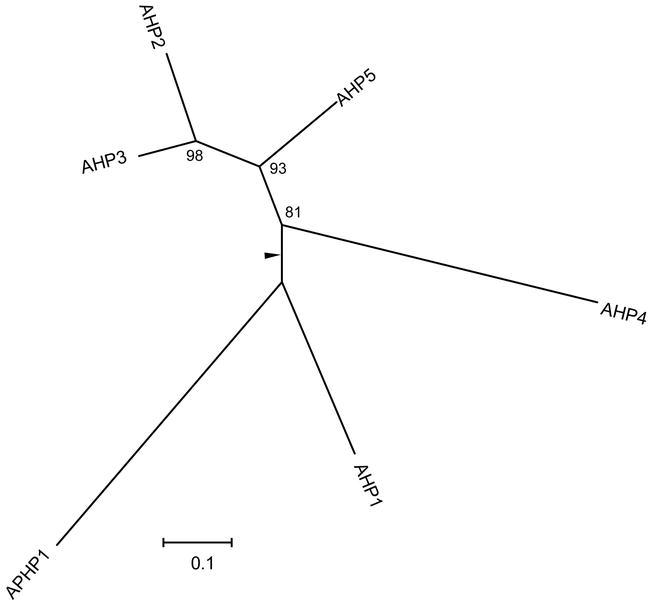

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic Relationship of HPt Proteins.

An unrooted bootstrapped tree is shown based on amino-acid alignment of HPt domain sequences.

Analysis of loss-of-function mutations has revealed that AHP1, AHP2, AHP3, and AHP5 function as redundant positive regulators of cytokinin signaling (Hutchison et al., 2006). AHP4 only contributes slightly to the cytokinin responses, and in some cases appears to act as a negative regulator (Hutchison et al., 2006). The AHPs have been shown to accumulate in the nucleus in response to exogenous cytokinin (Hwang and Sheen, 2001; Yamada et al., 2004). APHP1, which encodes a pseudo-HPt lacking the phosphorylation site, acts as a negative regulator of cytokinin responses (Mähönen et al., 2006b). APHP1 expression is induced by cytokinin and thus functions as part of a negative feedback loop to reduce the plants sensitivity to cytokinin, with APHP1 potentially interacting with the receiver domains of the cytokinin receptors to prevent phosphotransfer to bona-fide AHPs.

RESPONSE REGULATORS

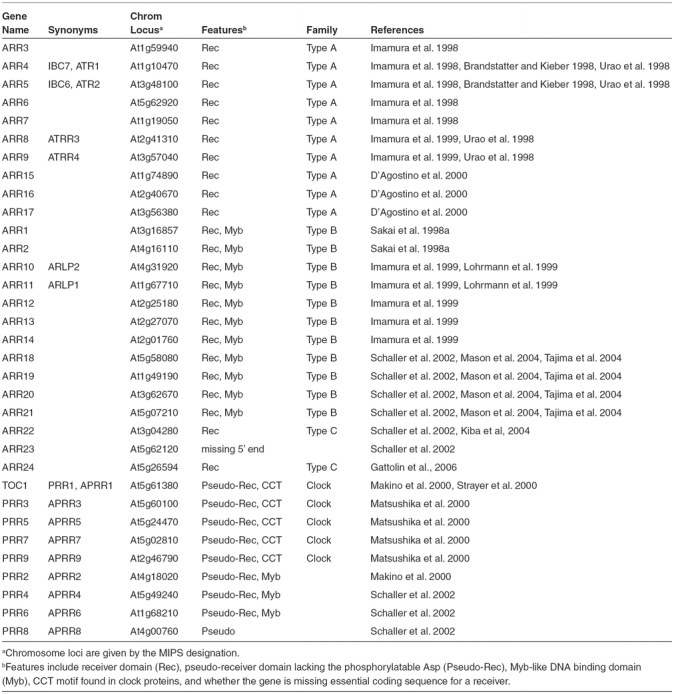

There are 23 genes in the Arabidopsis genome encoding proteins predicted to be functional response regulators (Table 3, Figures 2 and 5). These authentic response regulators (ARRs) can be divided into three classes based on phylogenetic analysis and function: type-A type-B, and type-C response regulators (Imamura et al., 1999; Schaller et al., 2007). In addition, there are nine genes encoding response regulators that lack the conserved Asp for phosphorylation, and are called pseudo-response regulators (PRRs) (Makino et al., 2000).

Table 3.

Response Regulators of Arabidopsis

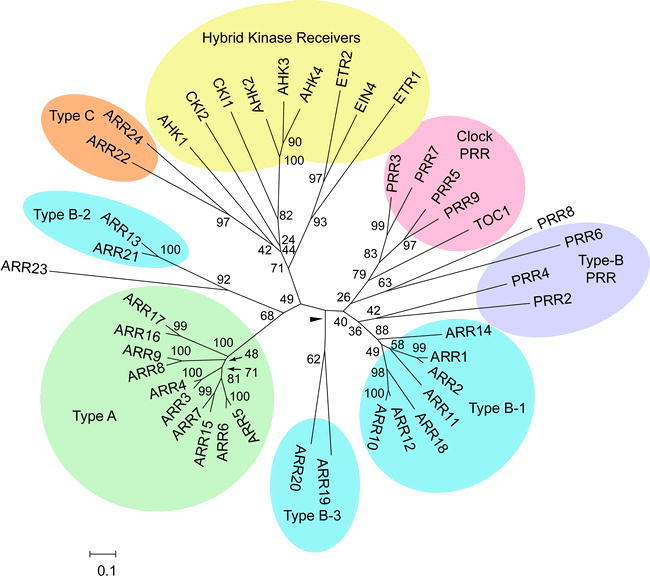

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic Relationship of Receiver Domains from Response Regulators and Hybrid Kinases.

An unrooted bootstrapped tree is shown based on amino-acid alignment of receiver and pseudoreceiver domain sequences. The different families of receiver domains are highlighted, with subfamilies 1, 2 and 3 being indicated for the type-B ARRs. Note that the tree has some low bootstrap values indicating that regions of this tree should be considered to be simply radiations.

Type-A response regulators

The type-A response regulators are relatively small, containing a receiver domain along with short N- and C-terminal extensions (Brandstatter and Kieber, 1998; Imamura et al., 1998; Urao et al., 1998). Members of the type-A family are transcriptionally induced to varying extents by cytokinin (Brandstatter and Kieber, 1998; Taniguchi et al., 1998; D'Agostino et al., 2000), and cytokinin also stabilizes some type-A ARR proteins in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (To et al., 2007). Genetic analyses indicate that ARR3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 15 function as negative regulators of cytokinin signaling, thus participating in a negative feedback loop to reduce the plant sensitivity to cytokinin (Kiba et al., 2003; To et al., 2004; Leibfried et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2007; To et al., 2007).

Some type-A ARRs are also implicated in other regulatory pathways. ARR4 interacts with phytochrome B to modulate its activity, allowing for cross-talk between the cytokinin and light signaling pathways (Sweere et al., 2001; Mira-Rodado et al., 2007). WUSCHEL, a regulator of stem cells in the shoot apical meristem, negatively regulates transcription of several type-A ARRs, revealing cross-talk between cytokinin signaling and a key meristem identity gene (Leibfried et al., 2005). ARR3 and ARR4 regulate the circadian period in a cytokinin-independent manner, with loss of these two genes resulting in a longer clock period (Salomé et al., 2006).

Type-B response regulators

The type-B ARRs differ from the type-A ARRs in that the type-B ARRs contain long C-terminal extensions with a Myb-like DNA binding domain referred to as the GARP domain (Imamura et al., 1999; Hosoda et al., 2002). Multiple lines of evidence support the role of the type-B ARRs as transcription factors (Sakai et al., 2000; Imamura et al., 2001; Lohrmann et al., 2001; Sakai et al., 2001; Hosoda et al., 2002; Imamura et al., 2003; Mason et al., 2004; Mason et al., 2005; Rashotte et al., 2006). Type-B ARRs are nuclear-localized in Arabidopsis and capable of transcriptional activation when expressed in yeast (Lohrmann et al., 1999; Sakai et al., 2000; Lohrmann et al., 2001). The ARR1, ARR2, and ARR10 type-B response regulators bind to a core DNA sequence 5′-(G/A)GAT(T/C)-3′ (Sakai et al., 2000; Hosoda et al., 2002).

The eleven type-B ARRs of Arabidopsis fall into three subfamilies based on phylogenetic analysis: subfamily 1 contains seven members (ARR1, ARR2, ARR10, ARR11, ARR12, ARR14, and ARR18); subfamily 2 contains two members (ARR13 and ARR21); and subfamily 3 is also comprised of two members (ARR19 and ARR20) (Mason et al., 2004). Genetic analyses indicate that at least five subfamily-1 members mediate cytokinin signaling, with ARR1, ARR10, and ARR12 appearing to play key roles (Mason et al., 2005; Yokoyama et al., 2007; Ishida et al., 2008). The cytokinin transcriptional response is substantially reduced in type-B mutant backgrounds, supporting a central role of the type-B ARRs in the cytokinin signaling pathway (Rashotte et al., 2006; Yokoyama et al., 2007). A number of primary response genes directly regulated by the type-B ARRs have been identified, including the type-A ARRs (Taniguchi et al., 2007). It has been proposed that the subfamily-1 member ARR2 may modulate ethylene signaling, but the effect is subtle and differing results have been obtained in the analysis of arr2 mutants, perhaps due to differing growth conditions (Hass et al., 2004; Mason et al., 2005).

The functions of the subfamily-2 and subfamily-3 type-B ARRs are unclear. They are not as broadly expressed as the subfamily-1 ARRs (Mason et al., 2004; Tajima et al., 2004), and the only reported mutant phenotypes arise from overexpression of activated versions of the genes (Tajima et al., 2004; Kiba et al., 2005). Overexpression of activated ARR21 (subfamily-2) results in seedlings in which cell proliferation is activated to form callus-like structures. Overexpression of activated ARR20 (subfamily-3) results in plants that develop small flowers and abnormal siliques with reduced fertility.

Type-C response regulators

Arabidopsis also contains two additional response regulators (ARR22 and 24). These lack long C-terminal extensions, like the type-A ARRs, but are not closely related to the type-A ARRs based on phylogenetic analysis (Figure 5) (Kiba et al., 2004; Schaller et al., 2007). The type-C ARRs are also not transcriptionally regulated by cytokinin. The type-C ARR sequences are more similar to the hybrid-kinase receiver domains than to other response regulators (Figure 5), raising the possibility that a histidine kinase, rather than an HPt protein, could serve as their phosphodonor. ARR22 and ARR24 are predominantly expressed in flowers and siliques (Kiba et al., 2004; Gattolin et al., 2006). Single and double loss-of-function mutants grow similarly to wild-type (Gattolin et al., 2006). Overexpression of ARR22 inhibits cytokinin signaling based on the transgenic lines having reduced shoot growth, poor root development, reduced cytokinin-responsive gene induction, and insensitivity to cytokinin under conditions for callus production (Kiba et al., 2004; Kiba et al., 2005; Gattolin et al., 2006). Whether the type-C ARRs normally antagonize the cytokinin signaling pathway is not known.

Pseudo-response regulators

Arabidopsis contains nine pseudo-response regulators termed PRRs (Table 3, Figures 2 and 5). These contain complete receiver domains but are missing essential residues required for activity (Makino et al., 2000). In particular, the aspartate that serves as a site for phosphorylation is missing, in many cases being replaced by a glutamate residue that may mimic the phosphorylated form. These also contain C-terminal extensions, some members with a CCT-motif (PRR1/TOC1, PPR3, PRR5, PRR7, and PRR9) and others with the Myb-like motif found in the type-B response regulators (PRR2, PRR4, and PRR6).

The pseudoresponse-regulators with the CCT motif are involved in the regulation of circadian rhythms and participate in multiple regulatory feedback loops in recent models for the Arabidopsis clock (Mizuno, 2005; Gardner et al., 2006; McClung, 2006). PRR1/TOC1 was identified in a forward genetic screen due to a semi-dominant mutation (timing of cab expression 1-1) that had shortened circadian periods for leaf movement, stomatal conductance, and several molecular markers (Millar et al., 1995; Somers et al., 1998; Strayer et al., 2000). PRR1/TOC1 participates in a feedback loop involving the other well-known clock components, CCA1 and LHY (Alabadi et al., 2001). Evidence that all the CCT-motif PRRs participate in the clock came from the discovery that their expression varies in a circadian manner (Matsushika et al., 2000; Makino et al., 2001) and that loss-of-function mutants have altered circadian periods (Kaczorowski and Quail, 2003; Michael et al., 2003; Farré et al., 2005; Nakamichi et al., 2005b; Nakamichi et al., 2005a; Salomé and McClung, 2005; Ito et al., 2008). The current model places PRR5, PRR7, and PRR9 in a feedback loop that also involves CCA1 and LHY. Recent work indicates that protein stability of TOC1, PRR5, PRR7, and PRR9 is post-translationally regulated (Farré and Kay, 2007; Ito et al., 2007; Kiba et al., 2007; Para et al., 2007). Additionally, PRR7 is phosphorylated, presumably on serine/threonine residues since it lacks the canonical phospho-acceptor aspartate, which may serve as a means to regulate its stability and/or function (Farré and Kay, 2007).

Potential Pseudogenes

Arabidopsis also contains the predicted sequence for a response regulator (ARR23) that, although containing the phosphorylated aspartate, is predicted to lack the N-terminal domain of the receiver; no EST is reported and ARR23 could be a pseudogene. The gene product of At3g04270 also shows homology to receiver domains but is missing what would be its C-terminal end.

SIGNALING THROUGH PHOSPHORELAYS

A multi-step phosphorelay, rather than a simple two-component system, appears to be the major His-Asp signaling circuit employed by Arabidopsis. This possibility was initially raised by analysis of the Arabidopsis genome, which revealed a preponderance of hybrid kinases in Arabidopsis along with the presence of HPt proteins (Schaller et al., 2002). Subsequent analyses of protein-protein interactions using the yeast two-hybrid system supports interactions among the hybrid kinases with HPt proteins, and of the HPt proteins with both type-A and type-B response regulators, consistent with what would be expected in a multi-step phosphorelay (Imamura et al., 1999; Urao et al., 2000; Dortay et al., 2007). Finally, as described below, analysis of the cytokinin signaling pathway supports use of the multi-step phosphorelay in planta.

The cytokinin signaling pathway gives us our clearest picture of how two-component signaling elements have been adapted to signaling in plants (Hwang and Sheen, 2001; Haberer and Kieber, 2002; Heyl and Schmülling, 2003; Kakimoto, 2003; To and Kieber, 2008). Genetic analyses using loss-of-function mutations indicate that the primary cytokinin signaling pathway is a positive regulatory circuit that requires hybrid histidine kinases (AHK2, AHK3, and AHK4) (Inoue et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2001; Ueguchi et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2001; Kakimoto, 2003; Kim et al., 2006), HPt proteins (AHP1, AHP2, AHP3, AHP5) (Hutchison et al., 2006), and type-B response regulators (ARR1, ARR2, ARR10, ARR11, and ARR12) (Sakai et al., 2001; Mason et al., 2005; Yokoyama et al., 2007; Ishida et al., 2008) (Figure 6). The function of type-B ARRs as transcription factors indicates that signals may move from histidine kinase to the nucleus solely through elements of a two-component system, the same type of signaling circuit employed by many prokaryotes. The mobile element of this signaling circuit are the AHPs, which relocate from cytosol to nucleus in response to cytokinin (Hwang and Sheen, 2001; Yamada et al., 2004). It should be noted that additional two-component signaling elements (such as other type-B ARRs) may also contribute to this cytokinin signaling circuit but this has not yet been confirmed genetically.

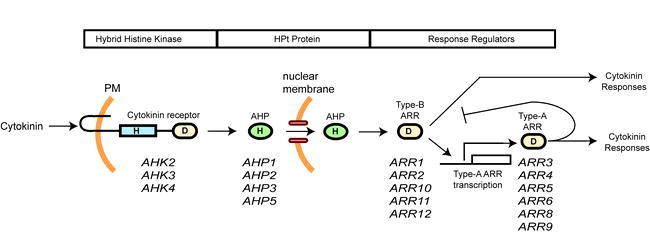

Figure 6.

Cytokinin Signal Transduction Occurs Through a Multi-Step Phosphorelay.

Cytokinin receptors, AHPs, and type-B ARRs function as a positive regulatory circuit to relay the cytokinin signal from plasma membrane to nucleus. Type-B ARRs act as transcription factors, one target being genes encoding type-A ARRs. The type-A ARRs feed back to inhibit their own transcription and may also mediate other cytokinin responses. The roles of the listed cytokinin receptors, AHPs, type-B response regulators, and type-A response regulators in cytokinin signal transduction have each been confirmed by the analysis of T-DNA insertion mutations.

Several negative regulatory circuits are also employed in cytokinin signaling. First, AHK4, like some bacterial histidine kinases, has both kinase and phosphatase activities (Mähönen et al., 2006a). In the absence of cytokinin, AHK4 acts as a phosphatase to dephosphorylate AHPs, thereby decreasing signaling through the phosphorelay. Upon cytokinin binding, AHK4 switches to act as a histidine kinase to initiate the multi-step phosphorelay, resulting in phosphorylation of AHPs and downstream response regulators. Second, one of the initial transcriptional responses mediated by the type-B ARRs in response to cytokinin is to induce the expression of the type-A ARRs (Brandstatter and Kieber, 1998; Imamura et al., 1998; D'Agostino et al., 2000; Mason et al., 2005; Rashotte et al., 2006; Taniguchi et al., 2007; Yokoyama et al., 2007). The type-A ARRs then negatively regulate cytokinin signaling, potentially by competing with the type-B ARRs for phosphorylation by the AHPs (Kiba et al., 2003; To et al., 2004; Leibfried et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2007; To et al., 2007). Furthermore, multiple type-A proteins are stabilized by cytokinin, further increasing this negative feedback loop (To et al., 2007). Third, the pseudo-HPt, APHP1, is induced by cytokinin and acts as a negative regulator of cytokinin responses (Mähönen et al., 2006b).

The presence of additional hybrid histidine-kinases in Arabidopsis, such as ETR1, AHK1, CKI1, and CKI2, suggests that multi-step phosphorelays function in relaying signals other than cytokinin. This raises the question as to which downstream components are involved in relaying the additional signals, given that a majority of the two-component signaling elements have already been implicated in cytokinin signaling. While there exists a formal possibility for unique combinations of signaling elements, it is far more likely that downstream signaling elements are shared among the receptors. In some cases, different input signals may be channeled into the same downstream signaling pathway to regulate a common response. Alternatively, a response tailored to a specific signal input could still be obtained even with shared signaling elements. One way to accomplish this would be to have varying affinities between the receptors and the AHPs, and between the AHPs and the response regulators, such that each signal would differentially activate the downstream components. Yeast two-hybrid analysis does suggest some specificity to the interactions between receptors and the AHPs (Urao et al., 2000), but the physiological relevance of these differences has not been determined. An alternative possibility would be for specificity of the downstream signaling elements to be modified by covalent modification or protein-protein interaction in ways unique to the signal input. It is also possible that protein subsets are sequestered in unique signaling complexes by scaffold proteins. Genetic, molecular, and proteomic approaches should clarify how this network of interactions functions in plants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dennis Mathews, Mike Gribskov, and John Walker for their assistance in writing the previous version of this review (Schaller et al., 2002). We thank Takeshi Mizuno and Tatsuo Kakimoto for their assistance with naming the two-component signaling elements, which resulted in the unified gene nomenclature adopted in 2002. Research in the authors' laboratories has been supported by grants from the National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and the U. S. Department of Agriculture.

Footnotes

Citation: Schaller G.E., Kieber J.J., and Shiu S. (2008) Two-Component Signaling Elements and Histidyl-Aspartyl Phosphorelays. The Arabidopsis Book 6:e0112. doi:10.1199/tab.0112

elocation-id: e0112

This chapter was updated on July 14, 2008. The original version has been archived and is available in PDF format at http://dx.doi.org/10.1199/tab.0086.

REFERENCES

- Alabadi D., Oyama T., Yanovsky M. J., Harmon F. G., Mas P., Kay S. A. Reciprocal regulation between TOC1 and LHY/CCA1 within the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Science. 2001;2936(1):880–883. doi: 10.1126/science.1061320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaman V., Aravind L. The CHASE domain: a predicted ligand-binding module in plant cytokinin receptors and other eukaryotic and bacterial receptors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;266(1):579–582. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01968-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby J. L., Parkinson J. S., Bourret R. B. Signal transduction via the multi-step phosphorelay: not necessarily a road less traveled. Cell. 1996;866(1):845–848. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. D., Wolanin P. M., Stock J. B. Signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis. Bioessays. 2006;286(1):9–22. doi: 10.1002/bies.20343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder B. M., O'Malley R C., Wang W., Moore J. M., Parks B. M., Spalding E. P., Bleecker A. B. Arabidopsis seedling growth response and recovery to ethylene. A kinetic analysis. Plant Physiol. 2004;1366(1):2913–2920. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.050369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleecker A. B. Ethylene perception and signaling: an evolutionary perspective. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;46(1):269–274. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstatter I., Kieber J. J. Two genes with similarity to bacterial response regulators are rapidly and specifically induced by cytokinin in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;106(1):1009–1019. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.6.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Kwok S. F., Bleecker A. B., Meyerowitz E. M. Arabidopsis ethylene response gene ETR1: Similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science. 1993;2626(1):539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.8211181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. F., Etheridge N., Schaller G. E. Ethylene signal transduction. Ann. Bot. (Lond) 2005;956(1):901–915. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack T., Mathews S., Sharrock R. A. The phytochrome apoprotein family in Arabidopsis is encoded by five genes: the sequences and expression of PHYD and PHYE. Plant Mol. Biol. 1994;256(1):413–427. doi: 10.1007/BF00043870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino I. B., Deruere J., Kieber J. J. Characterization of the response of the Arabidopsis response regulator gene family to cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 2000;1246(1):1706–1717. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dortay H., Mehnert N., Mehnert L., Mehnert B., Mehnert T., Mehnert S., Mehnert A, H. Analysis of protein interactions within the cytokinin-signaling pathway of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS J. 2007;2736(1):4631–4644. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré E. M., Kay S. A. PRR7 protein levels are regulated by light and the circadian clock in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007;526(1):548–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré E. M., Harmer S. L., Harmon F. G., Yanovsky M. J., Kay S. A. Overlapping and distinct roles of PRR7 and PRR9 in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Curr. Biol. 2005;156(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble R. L., Coonfield M. L., Schaller G. E. Histidine kinase activity of the ETR1 ethylene receptor from Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;956(1):7825–7829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M. J., Hubbard K. E., Hotta C. T., Dodd A. N., Webb A. A. How plants tell the time. Biochem. J. 2006;3976(1):15–24. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattolin S., Alandete-Saez M., Elliot K., Gonzalez-Carranza Z., Naomab E., Powell C., Roberts J. A. Spatial and temporal expression of the response regulators ARR22 and ARR24 in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;576(1):4225–4233. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer G., Kieber J. J. Cytokinins. New insights into a classic phytohormone. Plant Physiol. 2002;1286(1):354–362. doi: 10.1104/pp.010773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. E., Findell J. L., Schaller G. E., Sisler E. C., Bleecker A. B. Ethylene perception by the ERS1 protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;1236(1):1449–1458. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass C., Lohrmann J., Albrecht V., Sweere U., Hummel F., Yoo S. D., Hwang I., Zhu T., Schafer E., Kudla J., Harter K. The response regulator 2 mediates ethylene signalling and hormone signal integration in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2004;236(1):3290–3302. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejatko J., Pernisova M., Eneva T., Palme K., Brzobohaty B. The putative sensor histidine kinase CKI1 is involved in female gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2003;2696(1):443–453. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0858-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyl A., Schmülling T. Cytokinin signal perception and transduction. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003;66(1):480–488. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyl A., Wulfetange K., Pils B., Nielsen N., Romanov G. A., Romanov T. D. S. Evolutionary proteomics identifies amino acids essential for ligand-binding of the cytokinin receptor CHASE domain. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;76(1):62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M., Pischke M. S., Mahonen A. P., Miyawaki K., Hashimoto Y., Seki M., Kobayashi M., Shinozaki K., Kato T., Tabata S., Helariutta Y., Sussman M. R., Kakimoto T. In planta functions of the Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;1016(1):8821–8826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402887101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda K., Imamura A., Katoh E., Hatta T., Tachiki M., Yamada H., Mizuno T., Yamazaki T. Molecular structure of the GARP family of plant Myb-related DNA binding motifs of the Arabidopsis response regulators. Plant Cell. 2002;146(1):2015–2029. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J., Chang C., Sun Q., Meyerowitz E. M. Ethylene sensitivity conferred by Arabidopsis ERS gene. Science. 1995;2696(1):1712–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.7569898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J., Sakai H., Nourizadeh S., Chen Q. G., Bleecker A. B., Ecker J. R., Meyerowitz E. M. Ein4 and ERS2 are members of the putative ethylene receptor family in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;106(1):1321–1332. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;806(1):225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T., Plowman G. D. The protein kinases of budding yeast: six score and more. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997;226(1):18–22. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison C. E., Li J., Argueso C., Gonzalez M., Lee E., Lewis M. W., Maxwell B. B., Perdue T. D., Schaller G. E., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., Kieber J. J. The Arabidopsis histidine phosphotransfer proteins are redundant positive regulators of cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell. 2006;186(1):3073–3087. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I., Sheen J. Two-component circuitry in Arabidopsis cytokinin signal transduction. Nature. 2001;4136(1):383–389. doi: 10.1038/35096500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura A., Yoshino Y., Mizuno T. Cellular localization of the signaling components of Arabidopsis His-to-Asp phosphorelay. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001;656(1):2113–2117. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura A., Kiba T., Tajima Y., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. In vivo and in vitro characterization of the ARR11 response regulator implicated in the His-to-Asp phosphorelay signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;446(1):122–131. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura A., Hanaki N., Umeda H., Nakamura A., Suzuki T., Ueguchi C., Mizuno T. Response regulators implicated in his-to-asp phosphotransfer signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;956(1):2691–2696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura A., Hanaki N., Nakamura A., Suzuki T., Taniguchi M., Kiba T., Ueguchi C., Sugiyama T., Mizuno T. Compilation and characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana response regulators implicated in His-Asp phosphorelay signal transduction. Plant Cell Physiol. 1999;406(1):733–742. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T., Higuchi M., Hashimoto Y., Seki M., Kobayashi M., Kato T., Tabata S., Shinozaki K., Kakimoto T. Identification of CRE1 as a cytokinin receptor from Arabidopsis. Nature. 2001;4096(1):1060–1063. doi: 10.1038/35059117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida K., Yamashino T., Yokoyama A., Mizuno T. Three type-B response regulators, ARR1, ARR10, and ARR12, play essential but redundant roles in cytokinin signal transduction throughout the life cycle of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;496(1):47–57. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S., Nakamichi N., Kiba T., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. Rhythmic and light-inducible appearance of clock-associated pseudo-response regulator protein PRR9 through programmed degradation in the dark in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;486(1):1644–1651. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S., Niwa Y., Nakamichi N., Kawamura H., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. Insight into missing genetic links between two evening-expressed pseudo-response regulator genes TOC1 and PRR5 in the circadian clock-controlled circuitry in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;496(1):201–213. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwami A., Yamashino T., Tanaka Y., Sakakibara H., Kakimoto T., Sato S., Kato T., Tabata S., Nagatani A., Mizuno T. AHK5 histidine kinaes regulates root elongation through an ETR1-dependent abscissic acid and ethylene signaling pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;486(1):375–380. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski K. A., Quail P. H. Arabidopsis PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR7 is a signaling intermediate in phytochrome-regulated seedling deetiolation and phasing of the circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2003;156(1):2654–2665. doi: 10.1105/tpc.015065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto T. CKI1, a histidine kinase homologue involved in cytokinin signal transduction. Science. 1996;2746(1):982–985. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto T. Perception and signal transduction of cytokinins. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2003;546(1):605–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T., Aoki K., Sakakibara H., Mizuno T. Arabidopsis response regulator, ARR22, ectopic expression of which results in phenotypes similar to the wol cytokinin-receptor mutant. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;456(1):1063–1077. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T., Henriques R., Sakakibara H., Chua N. H. Targeted degradation of PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR5 by an SCFZTL complex regulates clock function and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2007;196(1):2516–2530. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T., Naitou T., Koizumi N., Yamashino T., Sakakibara H., Mizuno T. Combinatorial microarray analysis revealing arabidopsis genes implicated in cytokinin responses through the His->Asp Phosphorelay circuitry. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;466(1):339–355. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T., Yamada H., Sato S., Kato T., Tabata S., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. The type-A response regulator, ARR15, acts as a negative regulator in the cytokinin-mediated signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;446(1):868–874. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Ryu H., Hong S. H., Woo H. R., Lim P. O., Lee I. C., Sheen J., Nam H. G., Hwang I. Cytokinin-mediated control of leaf longevity by AHK3 through phosphorylation of ARR2 in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;1036(1):814–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505150103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. J., Park J. Y., Ku S. J., Ha Y. M., Kim S., Kim M. D., Oh M. H., Kim J. Genome-wide expression profiling of ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR 7(ARR7) overexpression in cytokinin response. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2007;2776(1):115–137. doi: 10.1007/s00438-006-0177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibfried A., To J. P. C., Stehling S., Kehle A., Busch W., Demar M., Kieber J. J., Lohmann J. U. WUSCHEL controls meristem size by direct transcriptional regulation of cytokinin inducible response regulators. Nature. 2005;4386(1):1172–1175. doi: 10.1038/nature04270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrmann J., Buchholz G., Keitel C., Sweere U., Kircher S., Bäurle I., Kudla J., Schäfer E., Harter K. Differential expression and nuclear localization of response regulator-like proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant. Biol. 1999;16(1):495–505. [Google Scholar]

- Lohrmann J., Sweere U., Zabaleta E., Baurle I., Keitel C., Kozma-Bognar L., Brennicke A., Schafer E., Kudla J., Harter K. The response regulator ARR2: a pollen-specific transcription factor involved in the expression of nuclear genes for components of mitochondrial complex I in Arabidopsis. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2001;2656(1):2–13. doi: 10.1007/s004380000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis W. F., Shaulsky G., Wang N. Histidine kinases in signal transduction pathways of eukaryotes. J. Cell Science. 1997;1106(1):1141–1145. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.10.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mähönen A. P., Higuchi M., Törmäkangas K., Miyawaki K., Pischke M. S., Sussman M. R., Helariutta Y., Kakimoto T. Cytokinins regulate a bidirectional phosphorelay network in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2006a;166(1):1116–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mähönen A. P., Bishopp A., Higuchi M., Nieminen K. M., Kinoshita K., Tormakangas K., Ikeda Y., Oka A., Kakimoto T., Helariutta Y. Cytokinin signaling and its inhibitor AHP6 regulate cell fate during vascular development. Science. 2006b;3116(1):94–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1118875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S., Matsushika A., Kojima M., Oda Y., Mizuno T. Light response of the circadian waves of the APRR1/TOC1 quintet: when does the quintet start singing rhythmically in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;426(1):334–339. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S., Kiba T., Imamura A., Hanaki N., Nakamura A., Suzuki T., Taniguchi M., Ueguchi C., Sugiyama T., Mizuno T. Genes encoding pseudo-response regulators: insight into His-to-Asp phosphorelay and circadian rhythm in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;416(1):791–803. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.6.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. G., Li J., Mathews D. E., Kieber J. J., Schaller G. E. Type-B response regulators display overlapping expression patterns in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;1356(1):927–937. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.038109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. G., Mathews D. E., Argyros D. A., Maxwell B. B., Kieber J. J., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., Schaller G. E. Multiple type-B response regulators mediate cytokinin signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;176(1):3007–3018. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushika A., Makino S., Kojima M., Mizuno T. Circadian waves of expression of the APRR1/TOC1 family of pseudo- response regulators in Arabidopsis thaliana: insight into the plant circadian clock. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;416(1):1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcd043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung C. R. Plant circadian rhythms. Plant Cell. 2006;186(1):792–803. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.040980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael T. P., Salome P. A., Yu H. J., Spencer T. R., Sharp E. L., McPeek M. A., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., McClung C. R. Enhanced fitness conferred by naturally occurring variation in the circadian clock. Science. 2003;3026(1):1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.1082971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A. J., Carré I. A., Strayer C. A., Chua N. H., Kay S. A. Circadian clock mutants in Arabidopsis identified by luciferase imaging. Science. 1995;2676(1):1161–1163. doi: 10.1126/science.7855595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mira-Rodado V., Sweere U., Grefen C., Kunkel T., Fejes E., Nagy F., Schäfer E., Harter K. Functional cross-talk between two-component and phytochrome B signal transduction in Arabidopsis. J Exp. Bot. 2007;586(1):2595–2607. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata S-i, Urao T., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. Characterization of genes for two-component phosphorelay mediators with a single HPt domain in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 1998;4376(1):11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T. Compilation of all genes encoding two-component phosphotransfer signal transducers in the genome of Escherichia coli. DNA Res. 1997;46(1):161–168. doi: 10.1093/dnares/4.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T. Two-component phosphorelay signal transduction systems in plants: from hormone responses to circadian rhythms. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005;696(1):2263–2276. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussatche P., Klee H. J. Autophosphorylation activity of the Arabidopsis ethylene receptor multigene family. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;2796(1):48734–48741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamichi N., Kita M., Ito S., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORS, PRR9, PRR7 and PRR5, together play essential roles close to the circadian clock of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005a;466(1):686–698. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamichi N., Kita M., Ito S., Sato E., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. The Arabidopsis pseudo-response regulators, PRR5 and PRR7, coordinately play essential roles for circadian clock function. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005b;466(1):609–619. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura C., Ohashi Y., Sato S., Kato T., Tabata S., Ueguchi C. Histidine kinase homologs that act as cytokinin receptors possess overlapping functions in the regulation of shoot and root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;166(1):1365–1377. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Para A., Farre E. M., Imaizumi T., Pruneda-Paz J. L., Harmon F. G., Kay S. A. PRR3 Is a vascular regulator of TOC1 stability in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2007;196(1):3462–3473. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson J. S. Signal transduction schemes of bacteria. Cell. 1993;736(1):857–871. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90267-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pischke M. S., Jones L. G., Otsuga D., Fernandez D. E., Drews G. N., Sussman M. R. An Arabidopsis histidine kinase is essential for megagametogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;996(1):15800–15805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232580499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plowman G. D., Sudarsanam S., Bingham J., Whyte D., Hunter T. The protein kinases of Caenorhabditis elegans: a model for signal transduction in multicellular organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;966(1):13603–13610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov K. M., Kedishvili N. Y., Zhao Y., Shimomura Y., Crabb D. W., Harris R. A. Primary structure of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase establishes a new family of eukaryotic protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;2686(1):26602–26606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X., Schaller G. E. Requirement of the histidine kinase domain for signal transduction by the ethylene receptor ETR1. Plant Physiol. 2004;1366(1):2961–2970. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.047126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashotte A. M., Mason M. G., Hutchison C. E., Ferreira F. J., Schaller G. E., Kieber J. J. A subset of Arabidopsis AP2 transcription factors mediates cytokinin responses in concert with a two-component pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;1036(1):11081–11085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602038103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser V., Raitt D. C., Saito H. Yeast osmosensor SLn1 and plant cytokinin receptor Cre1 respond to changes in turgor pressure. J. Cell Biol. 2003;1616(1):1035–1040. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riefler M., Novak O., Strnad M., Schmulling T. Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor mutants reveal functions in shoot growth, leaf senescence, seed size, germination, root development, and cytokinin metabolism. Plant Cell. 2006;186(1):40–54. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell N. C., Su Y-S., Lagarias J. C. Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;576(1):837–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez F. I., Esch J. J., Hall A. E., Binder B. M., Schaller G. E., Bleecker A. B. A copper cofactor for the ethylene receptor ETR1 from Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;2836(1):996–998. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H., Aoyama T., Oka A. Arabidopsis ARR1 and ARR2 response regulators operate as transcriptional activators. Plant J. 2000;246(1):703–711. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H., Hua J., Chen Q. G., Chang C., Medrano L. J., Bleecker A. B., Meyerowitz E. M. ETR2 is an ETR1-like gene involved in ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;956(1):5812–5817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H., Honma T., Aoyama T., Sato S., Kato T., Tabata S., Oka A. ARR1, a transcription factor for genes immediately responsive to cytokinins. Science. 2001;2946(1):1519–1521. doi: 10.1126/science.1065201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomé P. A., McClung C. R. PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR 7 and 9 are partially redundant genes essential for the temperature responsiveness of the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2005;176(1):791–803. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomé P. A., To J. P., Kieber J. J., McClung C. R. Arabidopsis response regulators ARR3 and ARR4 play cytokinin-independent roles in the control of circadian period. Plant Cell. 2006;186(1):55–69. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller G. E. Histidine kinases and the role of two-component systems in plants. Adv. Bot. Res. 2000;326(1):109–148. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller G. E., Bleecker A. B. Ethylene-binding sites generated in yeast expressing the Arabidopsis ETR1 gene. Science. 1995;2706(1):1809–1811. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller G. E., Mathews D. E., Gribskov M., Walker J. C. Two-component signaling elements and histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelays. Somerville C., Meyerowitz E., editors. The Arabidopsis Book. 2002;6(1):1–9. doi: 10.1199/tab.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller G. E., Doi K., Hwang I., Kieber J. J., Khurana J. P., Kurata N., Mizuno T., Pareek A., Shiu S-H., Wu P., Yip W. K. Letter to the Editor: Nomenclature for two-component signaling elements of Oryza sativa. Plant Physiol. 2007;1436(1):555–557. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J., Copley R. R., Doerks T., Ponting C. P., Bork P. SMART: a web-based tool for the study of genetically mobile domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;286(1):231–234. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock R. A., Quail P. H. Novel phytochrome sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana: structure, evolution, and differential expression of a plant regulatory photoreceptor family. Genes Dev. 1989;36(1):1745–1757. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers D. E., Webb A. A., Pearson M., Kay S. A. The short-period mutant, toc1-1, alters circadian clock regulation of multiple outputs throughout development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1998;1256(1):485–494. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock A. M., Robinson V. L., Goudreau P. N. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;696(1):183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayer C., Oyama T., Schultz T. F., Raman R., Somers D. E., Mas P., Panda S., Kreps J. A., Kay S. A. Cloning of the Arabidopsis clock gene TOC1, an autoregulatory response regulator homolog. Science. 2000;2896(1):768–771. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Imamura A., Ueguchi C., Mizuno T. Histidine-containing phosphotransfer (HPt) signal transducers implicated in His-to-Asp phosphorelay in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;396(1):1258–1268. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Zakurai K., Imamura A., Nakamura A., Ueguchi C., Mizuno T. Compilation and characterization of histidine-containing phosphotransmitters implicated in His-to-Asp phosphorelay in plants: AHP signal transducers of Arabidopsis thaliana. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000;646(1):2482–2485. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Miwa K., Ishikawa K., Yamada H., Aiba H., Mizuno T. The arabidopsis sensor hiskinase, ahk4, can respond to cytokinins. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;426(1):107–113. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson R. V., Alex L. A., Simon M. I. Histidine and aspartate phosphorylation: two-component systems and the limits of homology. Trends Biochem. 1994;196(1):485–490. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweere U., Eichenberg K., Lohrmann J., Mira-Rodado V., Baurle I., Kudla J., Nagy F., Schafer E., Harter K. Interaction of the response regulator ARR4 with phytochrome B in modulating red light signaling. Science. 2001;2946(1):1108–1111. doi: 10.1126/science.1065022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima Y., Imamura A., Kiba T., Amano Y., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. Comparative Studies on the Type-B Response Regulators Revealing their Distinctive Properties in the His-to-Asp Phosphorelay Signal Transduction of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;456(1):28–39. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Suzuki T., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. Comparative studies of the AHP histidine-containing phosphotransmitters implicated in His-to-Asp phosphorelay in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004;686(1):462–465. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M., Sasaki N., Tsuge T., Aoyama T., Oka A. ARR1 directly activates cytokinin response genes that encode proteins with diverse regulatory functions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;486(1):263–277. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M., Kiba T., Sakakibara H., Ueguchi C., Mizuno T., Sugiyama T. Expression of Arabidopsis response regulator homologs is induced by cytokinins and nitrate. FEBS Lett. 1998;4296(1):259–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen J. J., Miernyk J. A., Randall D. D. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase from Arabidopsis thaliana: a protein histidine kinase that phosphorylates serine residues. Biochem J. 2000;3496(1):195–201. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To J. P., Haberer G., Ferreira F. J., Deruere J., Mason M. G., Schaller G. E., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., Kieber J. J. Type-A Arabidopsis response regulators are partially redundant negative regulators of cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell. 2004;166(1):658–671. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To J. P. C., Kieber J. J. Cytokinin signaling: two-components and more. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;136(1):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To J. P. C., Deruere J., Maxwell B. B., Morris V. F., Hutchison C. E., Ferreira F. J., Schaller G. E., Kieber J. J. Cytokinin regulates type-A Arabidopsis response regulator activity and protein stability via two-component phosphorelay. Plant Cell. 2007;196(1):3901–3914. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran L-S. P., Urao T., Qin F., Maruyama K., Kakimoto T., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Functional analysis of AHK1/ATHK1 and cytokinin receptor histidine kinases in response to abscisic acid, drought, and salt stress in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;1046(1):20623–20628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706547105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi C., Sato S., Kato T., Tabata S. The AHK4 gene involved in the cytokinin-signaling pathway as a direct receptor molecule in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;426(1):751–755. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urao T., Yakubov B., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. Stress-responsive expression of genes for two-component response regulator-like proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 1998;4276(1):175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urao T., Miyata S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. Possible His to Asp phosphorelay signaling in an Arabidopsis two-component system. FEBS Lett. 2000;4786(1):227–232. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urao T., Yakubov B., Satoh R., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Seki M., Hirayama T., Shinozaki K. A transmembrane hybrid-type histidine kinase in Arabidopsis functions as an osmosensor. Plant Cell. 1999;116(1):1743–1754. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.9.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Hall A. E., O'Malley R., Bleecker A. B. Canonical histidine kinase activity of the transmitter domain of the ETR1 ethylene receptor from Arabidopsis is not required for signal transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;1006(1):352–357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237085100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H., Koizumi N., Nakamichi N., Kiba T., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. Rapid response of Arabidopsis T87 cultured cells to cytokinin through His-to-Asp phosphorelay signal transduction. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004;686(1):1966–1976. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H., Suzuki T., Terada K., Takei K., Ishikawa K., Miwa K., Mizuno T. The Arabidopsis AHK4 histidine kinase is a cytokinin-binding receptor that transduces cytokinin signals across the membrane. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;426(1):1017–1023. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh K-C., Lagarias J. C. Eukaryotic phytochromes:Light-regulated serine/threonine protein kinases with histidine kinase ancestry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;956(1):13976–13981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A., Yamashino T., Amano Y., Tajima Y., Imamura A., Sakakibara H., Mizuno T. Type-B ARR Transcription Factors, ARR10 and ARR12, are Implicated in Cytokinin-Mediated Regulation of Protoxylem Differentiation in Roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;486(1):84–96. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]