Abstract

Although several reports have described a possible association between insulin-like growth factors-1 (IGF-1) and pancreatic cancer (PC) risk, this association has not been evaluated in the non-Caucasian population. To assess the impact of IGF-1 polymorphisms on PC risk in Japanese, we conducted a case-control study which compared the frequency of ten single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and haplotypes of IGF-1. SNPs were investigated using the TaqMan method in 176 patients with PC and 1402 control subjects. Exposure to risk factors was assessed from the results of a self-administered questionnaire. Associations and gene-environment interactions were examined using an unconditional logistic regression model. We did not observe any significant main effect of IGF-1 loci, but did find interactions between rs5742714 and past and/or current body-mass index (BMI) status. Among patients with BMI > 25 at age 20, an increased PC risk was observed with the addition of the minor allele for rs5742714 (trend P = 0.048) and rs6214 (P = 0.043). Among patients with current BMI > 25, an increased or decreased PC risk was observed with the addition of the minor allele for rs5742714 (trend P = 0.046), rs4764887 (P = 0.031) and rs5742612 (P = 0.038). Haplotype analysis of IGF-1 showed a significant association among patients who were either or both previously or currently overweight. These findings suggest that IGF-1 polymorphisms may affect the development of PC in the Japanese population in combination with obesity. Further studies to confirm these findings are warranted.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, SNPs, IGF-1, overweight, risk factor

Introduction

The incidence of pancreatic cancer (PC) is increasing in Japan, and this cancer is now the fifth-leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1 -5]. Early detection of PC in its operable stage is difficult and the potential of curative treatment, such as complete surgical removal, is limited. These characteristics give PC a five-year survival rate of only 5.5% [6]. These characteristics emphasize the importance of epidemiological approaches which aim to predict the risk of PC by identifying groups at high risk, and thereby decrease the number of PC deaths.

A number of possible risk factors for PC have been identified, including smoking, overweight, diabetes mellitus, alcohol consumption, and chronic pancreatitis [2, 7-11]. Familial aggregation of PC has also been reported, which may suggest the possible involvement of genetic factors in PC incidence [5, 12]. Several recent reports have described an association between insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and PC, and one study reported the effect of IGF-1 polymorphisms on the risk of PC in a Western population [4, 13, 14]. IGF-1 polymorphisms and elevated serum levels of IGF-1 have been associated with an increased risk of several cancers, including prostate, colorectal, stomach and breast [15-22], and IGF-1 is highly expressed in PC cells [23]. The IGF-1-mediated signaling pathway leads to increased proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis, and decreased apoptosis [24-26]. Moreover, some reports have indicated that overweight may exert its influence on cancer risk through its effects on the serum concentration of IGF-1 [4, 27].

Here, to further evaluate the potential impact of IGF-1 polymorphisms on PC risk, we conducted a case-control study to evaluate the effect of IGF -1 genotypes and haplotypes on PC risk in a Japanese population. In addition, because overweight is a well-known risk factor for PC and IGF-1 polymorphisms may affect the association between overweight and PC risk, we also assessed gene-environment interactions, including the interaction of IGF-1 genotypes and haplotypes with overweight.

Materials and methods

Study population

Case subjects were 176 PC patients with no prior history of cancer who were diagnosed at Aichi Cancer Center Hospital (ACCH), Nagoya, Japan, between January 2001 and November 2005. Control subjects were 1402 randomly selected non-cancer outpatient visitors to ACCH during the same period who had no history of any cancer. All subjects were enrolled at first visit to ACCH in the Hospital-based Epidemiological Research Program II at ACCH (HERPACC-II) between January 2001 and November 2005. The framework of HERPACC-II has been described elsewhere [28]. Briefly, all first-visit outpatients to ACCH aged 20-79 years are asked to fill out a self-administered questionnaire regarding their lifestyle before development of the current symptoms. Responses are checked by trained interviewers. Outpatients are also asked to provide a 7-mL blood sample. Approximately 95% of eligible subjects complete the questionnaire and 50% provide blood samples. All data are loaded into the HERPACC database, which is periodically synchronized with the hospital cancer registry system to update the data on cancer incidence. Approximately 35% of subjects (46% of male subjects and 28% of female subjects) were diagnosed with cancer within a year of first visit. In this study, we defined patients diagnosed with PC within a year of first visit as the case population. A total of 75.7% of PC cases had histological confirmation, of which 92.1% were ductal adenocarcinoma. Our previous study showed that the lifestyle patterns of first-visit outpatients to ACC corresponded with those of individuals randomly selected from Nagoya's general population, confirming the external validity of the study [29]. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Aichi Cancer Center and informed consent was obtained at first visit from all participants.

Selection and genotyping of IGF-1 polymorphisms

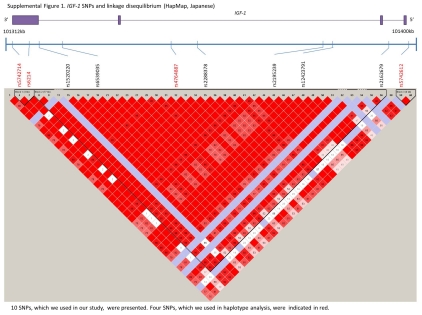

Based on the HapMap database for Japanese residing in Tokyo [30, 31], we selected tag single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for IGF-1 if they fit the following criteria: a minor allele frequency greater than 30% and a haplotype R-squared value greater than 0.80. We selected ten loci on the IGF-1 gene, namely rs5742714, rs6214, rs1520220, rs6539035, rs4764887, rs2288378, rs2195239, rs12423791, rs2162679, and rs5742612 (Supplemental Figure 1). DNA of each subject was extracted from the buffy coat fraction using a DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan). All loci were examined by the TaqMan method with probes and primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and Fluidigm EP1 SNP Genotyping 96.96 Dynamic Array (Fluidigm Corp., South San Francisco, CA). Approximately 10% of subjects were examined in duplicate to confirm consistency in genotyping.

Assessment of exposure

Exposure to potential PC risk factors was assessed using a self-administered questionnaire, which was completed before diagnosis during the first visit to ACCH. Responses were reviewed by trained interviewers. Subjects were specifically questioned about their lifestyle before the onset of the symptoms which impelled their visit to ACCH. Daily alcohol consumption in grams was determined by summing the pure alcohol amount in the average daily consumption of Japanese sake (rice wine), shochu (distilled spirit), beer, wine and whiskey, with one cup of Japanese sake (180 mL) considered equivalent to 23 g of ethanol; one drink of shochu (108 mL) to 23 g; one large bottle of beer (633 mL) to 23 g; one glass of wine (80 mL) to 10 g; and one shot of whiskey (28.5 mL) to 11.5 g. Cumulative smoking exposure was measured in pack-years (PY), the product of the average number of packs per day and the number of years of smoking. Height and body weight at baseline and weight at age 20 years were self-reported. Body mass index (BMI) at age 20 and current BMI were calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the height in meters squared, and expressed as kg/m2. Past history was also obtained from the self-administered questionnaire results. A family history of PC was considered positive when at least one parent or sibling had a history of PC.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 10 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, US). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Differences in characteristics between cases and controls were assessed using the chi-squared test. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using an unconditional logistic regression model adjusted for potential confounders. Potential confounders considered in multivariate analysis were age, sex (male or female), PY of smoking (<5, <20, <40, or >41), drinking habit (non-drinker, <23, <46, or >46 g/day), BMI at age 20 (<18.5, <22.5, <25, <30, or ≥30 kg/m2), current BMI (<18.4, <22.5, <25, <30, or ≥30 kg/ m2), history of diabetes mellitus (yes or no), and family history of PC (yes or no). As we had an a priori hypothesis about gene-environmental interaction between IGF-1 loci and a status as obese (defined as a BMI >25 kg/m2), we assessed this by including interaction terms in the models. In haplotype analysis, we used haplo-type-effects logistic regression for case-control data [32]. We also calculated gene-environment interactions under a case-only design [33] to confirm the robustness of our results. We evaluated linkage disequilibrium (LD) by means of linkage disequilibrium coefficients (R2). Accordance with the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) was assessed by the chi-squared test.

Results

Background characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 1. Men accounted for 68.2% of case subjects and 74.6% of controls. Compared to the control group, the case group had a significantly higher prevalence of heavy smoking (P = 0.010), higher prevalence of a history of diabetes mellitus (P < 0.001), higher BMI at age 20 (P = 0.014), and lower current BMI (P = 0.009).

Table 1.

Characteristics of case and control subjects

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | p-values* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=176 | n=1402 | ||||

| Age | 0.988 | ||||

| <40 | 10 | (5.68) | 73 | (5.21) | |

| >40 but <50 | 19 | (10.80) | 143 | (10.20) | |

| >50 but <60 | 59 | (33.52) | 462 | (32.95) | |

| >60but<70 | 55 | (31.25) | 466 | (33.24) | |

| >70 | 33 | (18.75) | 258 | (18.40) | |

| Sex | 0.067 | ||||

| Male | 12 | (68.18) | 1046 | (74.64) | |

| 0 | |||||

| Female | 56 | (31.82) | 356 | (25.39) | |

| BMI† at age 20 years (kg/m2) | 0.014 | ||||

| <18.5 | 14 | (7.95) | 165 | (11.77) | |

| ≥18.5 but <22.5 | 109 | (61.93) | 935 | (66.69) | |

| ≥22.5 but <25 | 36 | (20.45) | 219 | (15.62) | |

| ≥25 but <27.5 | 11 | (6.25) | 69 | (4.92) | |

| ≥27.5 | 6 | (3.41) | 14 | (1.00) | |

| Current BMI† (kg/m2) | 0.009 | ||||

| <18.5 | 15 | (8.52) | 59 | (4.21) | |

| ≥18.5 but <22.5 | 81 | (46.02) | 539 | (38.45) | |

| ≥22.5 but <25 | 42 | (23.86) | 465 | (33.17) | |

| ≥25 but <27.5 | 24 | (13.64) | 231 | (16.48) | |

| ≥27.5 | 14 | (7.95) | 108 | (7.70) | |

| Cigarette pack-years | 0.010 | ||||

| <5 | 67 | (38.07) | 619 | (44.15) | |

| ≥5 but <20 | 20 | (11.36) | 196 | (13.98) | |

| ≥20 but <40 | 33 | (18.75) | 297 | (21.18) | |

| ≥40 | 56 | (31.82) | 290 | (20.68) | |

| Drinking, gethanol/day | 0.464 | ||||

| None | 54 | (30.68) | 473 | (33.74) | |

| <23 | 50 | (28.41) | 412 | (29.39) | |

| >23 but <46 | 41 | (23.30) | 330 | (23.54) | |

| ≥46 | 31 | (17.61) | 187 | (13.34) | |

| History of diabetes mellitus | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 35 | (19.89) | 108 | (7.70) | |

| No | 141 | (80.11) | 1294 | (92.30) | |

| Family history of pancreatic cancer | 0.727 | ||||

| Yes | 8 | (4.55) | 56 | (3.99) | |

| No | 168 | (95.45) | 1346 | (96.01) | |

BMI: body mass index

Chi-squared test

Table 2 shows genotype distributions for the ten SNPs at the IGF-1 gene and their ORs and 95% CIs for PC risk. Seven of the ten SNPs (rs5742714, rs6214, rs1520220, rs4764887, rs2288378, rs2195239, and rs5742612) were in accordance with HWE while the remaining loci (rs6539035, rs 12423791, and rs2162679) were not. In addition, rs2288378 was in strong LD with rs5742714 (R2 = 0.91). These four loci (rs6539035, rs2288378, rs12423791, and rs2162679) were accordingly excluded from further analysis. Regarding the remaining six loci, no significant association with PC risk was seen by either genotype or per-allele model.

Table 2.

Associatin of IGF-1 polymorphisms on risk of pancreatic cancer

| Polymorphism | Genotype | No. of cases/controls (%) | ORs† (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs5742714 | GG | 106(60.23) / 861(61.41) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| GC | 64(36.36) / 463(33.02) | 1.13 (0.80 | |

| CC | 6(3.41) / 78(5.56) | 0.54 (0.22 | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (C) frequency in control subjects = 0.221 ( HWE‡: P = NS) | |||

| rs6214 | AA | 43(24.43) / 420(29.96) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| GA | 94(53.41) / 668(47.65) | 1.41 (0.95 | |

| GG | 39(22.16) / 314(22.40) | 1.20 (0.75 | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (G) frequency in control subjects = 0.462 ( P = NS) | |||

| rs1520220 | CC | 46(26.14) / 358(25.53) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| CG | 97(55.11) / 697(49.71) | 1.13 (0.77 | |

| GG | 33(18.75) / 347(24.75) | 0.74 (0.46 | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (G) frequency in control subjects = 0.496 ( P = NS) | |||

| rs6539035 | TT | 105(59.66) / 871(62.13) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| CT | 44(25.00) / 310(22.11) | 1.18 (0.80 | |

| CC | 27(15.76) / 221(15.76) | 0.96 (0.60 | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (C) frequency in control subjects = 0.268 ( P < 0.001) | |||

| rs4764887 | GG | 97(55.11) / 738(52.64) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| AG | 73(41.48) / 540(38.52) | 1.06 (0.76 | |

| AA | 6(3.41) / 124(8.84) | 0.40 (0.17 | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (A) frequency in control subjects = 0.281 ( P = NS) | |||

| rs2288378 | GG | 106(60.23) / 871(62.13) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| AG | 63(35.80) / 453(32.31) | 1.15 (0.81 - 1.63) | |

| AA | 7(3.98) / 78(5.56) | 0.64 (0.28 - 1.47) | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (A) frequency in control subjects = 0.217 ( P = NS) | |||

| rs2195239 | GG | 54(30.68) / 431(30.74) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| GC | 95(53.98) / 673(48.00) | 1.10 (0.76 - 1.59) | |

| CC | 27(15.34) / 298(21.26) | 0.72 <04 - 1.18) | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (C) frequency in control subjects = 0.453 ( P = NS) | |||

| rs12423791 | GG | 97(54.92) / 770(54.92) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| CG | 73(41.48) / 511(36.45) | 1.17 (0.83 - 1.63) | |

| CC | 6(3.41) / 121(8.63) | 0.42 (0.18 - 0.99) | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (C) frequency in control subjects = 0.269 ( P = 0.007) | |||

| rs2162679 | AA | 70(39.77) / 580(41.37) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| GA | 87(49.43) / 613(43.72) | 1.30 (0.91 - 1.84) | |

| GG | 19(10.80) / 209(14.91) | 0.77 (0.45 - 1.34) | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (G) frequency in control subjects = 0.368 ( P = 0.025) | |||

| rs5742612 | TT | 85(48.30) / 696(49.64) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| TC | 81(46.02) / 582(41.51) | 1.19 (0.85 - 1.66) | |

| CC | 10(5.68) / 124(8.84) | 0.68 (0.34 - 1.37) | |

| (P trend) | |||

| minor allele (C) frequency in control subjects = 0.296 ( P = NS) | |||

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, BMI at age 20 years, current BMI, smoking status, drinking habit, diabetes mellitus, and family history of pancreatic cancer

HWE: Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Test

To investigate the influence of IGF-1 genotype on the association between BMI and PC risk, we compared genotype distributions in subgroup analysis (Table 3 and 4). Among patients with BMI ≥ 25 at age 20, an increased PC risk was observed with the addition of the minor allele for rs5742714 (trend P = 0.048) and rs6214 (P = 0.043). Among patients with current BMI ≥ 25, an increased PC risk was observed with the addition of the minor allele for rs5742714 (trend P = 0.046), and a decreased risk with that for rs4764887 (P = 0.031) and rs5742612 (P = 0.038). Gene-environment interaction with BMI status (BMI < 25 or ≥ 25) at age 20 was marginally significant for rs5742714 (interaction P = 0.059). Interaction between current BMI status was significant for rs5742714 (interaction P = 0.029). In addition, to explore potential effect modification between potentially confounding factors and IGF-1 genotypes, we also performed subgroup analysis according to smoking status (<5 or ≥ 5 pack-year), history of diabetes mellitus (yes or no), drinking alcohol (<23 or ≥ 23 g ethanol/day) and family history of PC (yes or no), but no significant interactions were found.

Table 3.

Interaction between IGF-1 genotypes and BMI at age 20 on the risk of pancreatic cancer

| BMI at age 20 years < 25(kg/m2) | BMI at age 20 years >25(kg/m2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism | Genotype | No. of cases/controls (%) | ORst (95% Cl) | No. of cases/controls (%) | ORs† (95% Cl) | interaction P |

| rs5742714 | GG | 99(62.26) / 809(61.33) | 1.00 (ref.) | 7(41.18) / 52(62.65) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GC | 57(35.85) / 440(33.36) | 1.07 (0.75 - 1.52) | 7(41.18) / 23(27.71) | 3.33 (0.72 - 15.32) | ||

| CC | 3(1.89) / 70(5.31) | 0.32 (0.10 - 1.05) | 3(17.65) / 8(9.64) | 9.02 (1.23 - 66.21) | 0.059 | |

| (P trend) | 0.338 | |||||

| rs6214 | AA | 42(26.42) / 392(29.72) | 1.00 (ref.) | 1(5.88) / 28(33.73) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 83(52.20) / 636(48.22) | 1.22 (0.82 - 1.83) | 11(64.71) / 32(38.55) | 43.47 (2.48 - 763.21) | ||

| GG | 34(21.38) / 291(22.06) | 1.09 (0.67 - 1.77) | 5(29.41) / 23(27.71) | 38.26 (1.92 - 762.98) | 0.15 | |

| (P trend) | 0.715 | |||||

| rs1520220 | CC | 42(26.42) / 338(25.63) | 1.00 (ref.) | 4(23.53) / 20(24.10) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CG | 91(57.23) / 652(49.43) | 1.17 (0.79 - 1.75) | 6(35.29) / 45(54.22) | 0.67 (0.11 - 3.93) | ||

| GG | 26(16.35) / 329(24.94) | 0.64 (0.38 - 1.08) | 7(41.18) / 18(21.69) | 6.41 (0.79 - 52.31) | 0.219 | |

| (P trend) | 0.148 | |||||

| rs4764887 | GG | 87(54.72) / 694(52.62) | 1.00 (ref.) | 10(58.82) / 44(53.01) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| AG | 66(41.51) / 507(38.44) | 1.05 (0.74 - 1.50) | 7(41.18) / 33(39.76) | 1.18 (0.31 - 4.46) | ||

| AA | 6(3.77) / 118(8.95) | 0.43 (0.18 - 1.02) | 0(0.00) / 24(6.74) | n.e. | 0.524 | |

| (P trend) | 0.267 | 0.261 | ||||

| rs2195239 | GG | 50(31.45) / 409(31.01) | 1.00 (ref.) | 4(23.53) / 22(26.51) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GC | 87(54.72) / 628(47.61) | 1.14 (0.78 - 1.67) | 8(47.06) / 45(54.22) | 1.67 (0.28 - 9.80) | ||

| CC | 22(13.84) / 282(21.38) | 0.64 (0.38 - 1.10) | 5(29.41) / 16(19.28) | 4.91 (0.65 - 36.91) | 0.341 | |

| (P trend) | 0.227 | 0.415 | ||||

| rs5742612 | TT | 74(46.54) / 657(49.81) | 1.00 (ref.) | 11(64.71) / 39(46.99) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| TC | 75(47.17) / 542(41.09) | 1.26 (0.89 - 1.79) | 6(35.29) / 40(48.19) | 0.55 (0.14 - 2.19) | ||

| CC | 10(6.29) / 120(9.10) | 0.76 (0.37 - 1.53) | 0(0.00) / 4(4.82) | n.e. | 0.133 | |

| (P trend) | 0.856 | 0.121 | ||||

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, current BMI, smoking status, drinking habit, diabetes meiiitus, and family history of pancreatic cancer

Table 4.

Interaction between IGF-1 genotypes and current BMI on the risk of pancreatic cancer

| Current BMI < 25(kg/m2) |

Current BMI > 25(kg/m2) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism | Genotype | No. of cases/controls (%) | ORst (95% Cl) | No. of cases/controls (%) | ORst (95% Cl) | interaction P |

| rs5742714 | GG | 97(66.44) / 674(61.61) | 1.00 (ref.) | 16(42.11) / 207(61.06) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GC | 46(31.51) / 359(32.82) | 0.92 (0.62 - 1.37) | 19(50.00) / 113(33.33) | 2.47 (1.15 - 5.33) | ||

| CC | 3(2.05) / 61(5.8) | 0.30 (0.09 - 1.02) | 3(7.89) / 19(5.60) | 1.62 (0.38 - 6.90) | 0.029 | |

| (P trend) | 0.113 | 0.046 | ||||

| rs6214 | AA | 39(26.71) / 340(31.08) | 1.00 (ref.) | 8(21.05) / 94(27.73) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 79(54.11) / 512(46.80) | 1.38 (0.89 - 2.14) | 18(47.37) / 162(47.79) | 1.32 (0.52 - 3.36) | ||

| GG | 28(19.18) / 242(22.12) | 1.07 (0.62 - 1.84) | 12(31.58) / 83(24.48) | 1.87 (0.66 - 5.31) | 0.428 | |

| (P trend) | 0.711 | 0.192 | ||||

| rs1520220 | CC | 38(26.03) / 283(25.87) | 1.00 (ref.) | 9(23.68) / 84(24.78) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CG | 83(56.85) / 540(49.36) | 1.12 (0.73 - 1.72) | 19(50.00) / 171(50.44) | 1.08 (0.44 - 2.68) | ||

| GG | 25(17.12) / 271(24.77) | 0.62 (0.35 - 1.09) | 10(26.32) / 84(24.78) | 1.10 (0.39 - 3.10) | 0.539 | |

| (P trend) | 0.115 | 0.919 | ||||

| rs4764887 | GG | 72(52.17) / 567(53.34) | 1.00 (ref.) | 25(65.79) / 171(50.44) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| AG | 61(44.20) / 393(36.97) | 1.25 (0.86 - 1.83) | 12(31.58) / 147(43.36) | 0.50 (0.22 - 1.10) | ||

| AA | 5(3.62) / 107(9.78) | 0.42 (0.16 - 1.09) | 1(2.63) / 21(6.19) | 0.29 (0.03 - 2.49) | 0.114 | |

| (P trend) | 0.547 | 0.031 | ||||

| rs2195239 | GG | 44(31.88) / 333(31.33) | 1.00 (ref.) | 10(28.91) / 98(28.91) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GC | 74(53.62) / 505(47.51) | 1.08 (0.72 - 1.63) | 21(55.26) / 168(49.56) | 1.22 (0.52 - 2.89) | ||

| CC | 20(14.49) / 225(21.17) | 0.66 (0.37 - 1.17) | 7(18.42) / 73(21.53) | 1.00 (0.34 - 2.98) | 0.617 | |

| (P trend) | 0.206 | 0.844 | ||||

| rs5742612 | TT | 63(43.15) / 552(50.46) | 1.00 (ref.) | 23(60.53) / 161(47.49) | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| TC | 70(47.95) / 437(39.95) | 1.36 (0.93 - 2.00) | 15(39.47) / 155(45.72) | 0.66 (0.31 - 1.40) | ||

| CC | 13(8.90) / 105(9.60) | 0.90 (0.44 - 1.84) | 0(0.00) / 23(6.78) | n.e. | 0.06 | |

| (P trend) | 0.519 | 0.038 | ||||

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, BMI at age 20 years, smoking status, drinking habit, diabetes mellitus, and family history of pancreatic cancer

Haplotype analysis was conducted on four SNPs (rs5742714, rs6214, rs4764887, and rs5742612) which influenced the association between BMI and PC risk. The associations between IGF-1 haplotypes and PC risk are summarized in Table 5. Only haplotypes with frequencies > 0.01 in control subjects were examined. Compared to the most common haplotype, GAGT, the haplotype CGGT showed a nonsignificant risk elevation (adjusted OR = 2.83, 95%CI = 0.96 - 8.34) among patients with BMI ≥ 25 at age 20. Moreover, the interaction between haplotypes and BMI status at age 20 was significant for haplotype CGGT (interaction P = 0.041). Table 6 compares CGGT as a risk haplotype with the other haplotypes combined. Compared to the non-risk haplotypes, the risk haplotype showed elevated ORs of 2.34 (95% CI, 1.05 - 5.23) and 1.73 (95% Cl, 1.07 - 2.98) among patients with BMI ≥ 25 at age 20 and current BMI ≥ 25, respectively. The interaction between BMI status and the risk haplotype was also significant for BMI at age 20 (P = 0.017) and current BMI (interaction P = 0.009). Case-only analysis showed consistently significant interactions between BMI status and the risk haplotype.

Table 5.

Haplotype analysis of IGF-1 and risk for Dancreatic cancer

| Haplotypet | SNPs‡ | Haplotype Frequencies | Overall | Former BMI (at age 20) | Current BMI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (G>C) | 2 (A>G) | 3 (G>A) | 4 (T>C) | Overall | Cases | Controls | Adjusted§ OR (cases/controls 176/1402) | Adjusted†† OR BMI < 25 (cases/control s: 159/1319) | Adjusted†† OR BMI > 25 (cases/control s: 17/83) | Interaction with BMI status¶ (p-values) | Adjusted‡‡ OR BMI < 25 (cases/control s: 138/1063) | Adjusted‡‡ OR BMI > 25 (cases/control s: 38/339) | Interaction with BMI Status¶ (p-values) | |

| 1 | G | A | G | T | 0.245 | 0.238 | 0.246 | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| 2 | G | G | G | T | 0.199 | 0.238 | 0.194 | 1.11 (0.81-1.54) | 1.08 (0.77 -1.51) | 1.76 (0.56-5.55) | 0.409 | 1.23 (0.85-1.78) | 0.80 (0.39- 1.62) | 0.621 |

| 3 | G | G | G | C | 0.049 | 0.054 | 0.048 | 0.97 (0.56-1.68) | 1.02 (0.59-1.78) | n.e. | 0.986 | 1.15 (0.63-2.08) | 0.45 (0.10-2.00) | 0.316 |

| 4 | C | G | G | T | 0.216 | 0.217 | 0.216 | 0.99 (0.72-1.38) | 0.88 (0.62-1.25) | 2.83 (0.96-8.34) | 0.041 | 0.88 (0.60-1.29) | 1.35 (0.72-2.54) | 0.122 |

| 5 | G | A | A | T | 0.042 | 0.032 | 0.043 | 0.55 (0.25-1.22) | 0.51 (0.22-1.20) | 1.24 (0.13- 12.10) | 0.517 | 0.62 (0.26-1.47) | 0.33 (0.04-2.57) | 0.584 |

| 6 | G | A | A | C | 0.232 | 0.209 | 0.235 | 0.93 (0.67-1.28) | 0.92 (0.66-1.29) | 1.20 (0.35-4.04) | 0.803 | 1.03 (0.71-1.47) | 0.63 (0.30- 1.30) | 0.357 |

Only haplotype with frequencies > 0.01 in control subjects were examined

SNP 1 is rs5742714, 2 is rs6214, 3 is rs4764887, and 4 is rs5742612.

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, BMI at age 20 years, current BMI, smoking status, drinking habit, diabetes mellitus, and family history of pancreatic cancer

BMI status: BMI <25 or > 25

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, current BMI, smoking status, drinking habit, diabetes mellitus, and family history of pancreatic cancer

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, BMI at age 20 years, smoking status, drinking habit, diabetes mellitus, and family history of pancreatic cancer.

Table 6.

Risk of pancreatic cancer among subjects with hapiotype CGGT*

| Haplotype† | Overall | Former BMI (at age 20) | Current BMI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted§ OR | Adjusted‡‡ OR | Adjusted‡‡ OR | Interaction with BMI status¶ (p-value) | Interaction with BMI status¶ (p-value) (Case-only) | Adjusted§§ OR | Adjusted§§ OR | Interaction with BMI status¶ (p-value) | Interaction with BMI status¶ (p-value) (Case-only) | |

| All subjects (cases/controls 176/1402) | BMK25 (cases/controls: 159/1319) | BMI>25 (cases/controls: 17/83) | BMK25 (cases/controls: 138/1063) | BMI≥25 (cases/controls: 38/339) | |||||

| Other haplotypes†† | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) | - | - | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) | - | - |

| Hapiotype CGGT‡ | 1.01 (0.77 - 1.33) | 0.91 (0.68 - 1.22) | 2.34 (1.05 - 5.23) | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.83 (0.60-1.15) | 1.78 (1.07 - 2.98) | 0.009 | 0.009 |

Only haplotypes with frequencies > 0.01 were examined

Haplotype CGGT: IGF-1 SNPs atrs5742714, rs6214, rs4764887, and rs5742612

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, BMI at age 20 years, current BMI, smoking status, drinking habit, diabetes mellitus, and family history of pancreatic cancer

BMI status: BMI <25 or ≥ 25

Other haplotypes: except hapiotype CGGT

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, diabetes mellitus, current BMI, drinking habit, family history of pancreatic cancer, and smoking status

Multivariable adjustment by age, sex, diabetes mellitus, BMI at age 20 , drinking habit, family history of pancreatic cancer, and smoking status.

Discussion

In this case-control study, we demonstrated that IGF-1 polymorphisms affect PC risk in interaction with the status of obesity, defined by either or both an age 20 or current BMI ≥ 25. Four genetic variants in IGF-1, namely rs5742714, rs6214, rs4764887, and rs5742612, were identified as marker loci which were significantly associated with the risk of PC among overweight subjects. Our haplotype analysis revealed an elevated risk of PC by the risk haplotype CGGT among overweight subjects. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association between IGF-1 polymorphisms and the development of PC in a non-Caucasian population.

The functional consequences of SNPs at rs5742714, rs6214, rs4764887, and rs5742612 and haplotypes of IGF-1 are not fully elucidated. The locations of these SNPs at the IGF-1 gene are rs5742714 and rs6214 in the 3'untranslated region (UTR) of exon 4; rs4764887 in the intron 3; and rs5742612 in the 5'UTR of exon 1. Although these four loci does not cause any amino acid changes themselves, they may have regulatory functions or be linked with functional polymorphisms of the IGF-1 gene [13, 34-36]. With regard to rs5742714, the minor allele for this variant has been shown to be associated with increased levels of circulating IGF-1 and the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer [13, 17, 34, 37]. In our study, the minor allele for rs5742714 was significantly associated with elevated risk of PC among those with either or both an age 20 or current BMI ≥ 25. However, rs1520220, which is associated with a higher level of IGF-1 and the risk of several types of cancer [18, 20], was not associated with PC risk in our study.

To date, only one study has reported the effect of IGF-1 polymorphisms on the risk of PC [13, 38]. In that study, a haplotype of the IGF-1 gene containing the G allele for rs5742714 had a significantly lower frequency in PC cases than in controls, and the interaction between rs5742714 and diabetes mellitus on PC risk was significant [13]. In addition, the distribution of IGF-1 genotypes did not differ between PC cases and controls by BMI (< 25 or ≥ 25 kg/m2). In our present study, however, haplotype analysis of IGF-1 showed no relation with PC risk among all subjects, and there was no interaction between IGF-1 polymorphisms and diabetes mellitus with PC risk. Instead, we found an increased or decreased PC risk with the addition of the minor alleles for rs5742714, rs6214, rs4764887, and rs5742612 among overweight patients. Moreover, gene-environment interaction with BMI was significant for rs5742714, and haplotype analysis of IGF-1 also showed a significant association among overweight patients. Although the reason for these differences is unclear, the results may have been affected by the heterogeneity of study populations, differences in ethnicity, small sample size, and potential confounders. Further major study is essential.

Many reports have described an association between overweight and an elevated risk of several types of cancer, including PC [4, 8, 10, 38]. The mechanisms of this effect might be explained by an increase in bioavailable growth-factor production, such as of insulin and IGF-1 [4, 38]. These growth factors are produced in response to insulin resistance and promote cell cycling for tissue growth and repair [4]. In our study, the association between IGF-1 polymorphisms and the development of PC was observed only among subjects who were overweight. Although the function of the individual SNPs and haplotypes is not fully established, past and/or current overweight might influence PC risk through its effects on the activity of IGF-1, which is affected by IGF-1 polymorphisms. Here, we did not evaluate the association between changes in BMI status since age 20 and PC risk because the evaluation of BMI change in this setting is likely to introduce information bias, as PC patients in this study were likely to have presented with body weight loss. This point should be examined in a prospective study. Nevertheless, we found that IGF-1 polymorphisms were associated with PC risk among subjects who were overweight not only at age 20 but also at current status.

Our study has several methodological issues which warrant discussion. First, the control population was selected from non-cancer patients at ACCH. It is reasonable to assume that this was the same population from which the case subjects were derived, which would warrant the internal validity of the study. Second, with regard to external validity, we previously showed that individuals selected randomly from our control population were similar to the general population of Nagoya City in terms of exposures of interest [29]. Third, case-control studies have an intrinsic information bias. The HER-PACC system is less prone to this bias than typical hospital-based studies as the data for all patients are collected before diagnosis. Nonetheless, the assessment of exposure from self-administered questionnaires may be inaccurate and provide considerable variations. If present, however, any such misclassification would be non-differential, and would likely underestimate the causal association [39]. Forth, with regard to SNP analysis, our IGF-1 gene allele frequencies were comparable with information from the HapMap project [30, 31]. As we excluded IGF-1 loci showing HWE discordance, coverage of IGF-1 by tag SNPs was not as expected. Fifth, the power of our study is very limited due to small sample size, particularly in subgroup analysis; thus, a large-scale study should be conducted to verify our results. Lastly, our study was limited to a Japanese population, and the results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other populations.

In summary, we described that IGF-1 gene polymorphisms might be associated with the risk of PC in a Japanese population only among subjects who were overweight. These findings might support the proposed mechanism that overweight influences the risk of PC through its effects on the serum concentration of IGF-1. Further studies of these findings in larger cohorts should be conducted, and the mechanism by which these polymorphisms influence PC risk should be fully elucidated.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the efforts and contribution of doctors, nurses, technical staff, and hospital administration staff at ACCH for the daily management of the HERPACC study. This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; Grants-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan; Japan Society for the Promotion of Science A3 Foresight Program and a grant from Daiwa Securities Health Foundation.

Supplementary material

Supplemental Figure 1.

References

- 1. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services. Japan: N.C.C. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center 2007.

- 2.Kanda J, Matsuo K, Suzuki T, Kawase T, Hiraki A, Watanabe M, Mizuno N, Sawaki A, Yamao K, Tajima K, Tanaka H. Impact of alcohol consumption with polymorphisms in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes on pancreatic cancer risk in Japanese. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:296–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuda T, Marugame T, Kamo K, Katanoda K, Ajiki W, Sobue T. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2003: based on data from 13 population-based cancer registries in the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) Project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:850–858. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsugane S, Inoue M. Insulin resistance and cancer: epidemiological evidence. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1073–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low SK, Kuchiba A, Zembutsu H, Saito A, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Daigo Y, Kamatani N, Chiku S, Totsuka H, Ohnami S, Hirose H, Shimada K, Okusaka T, Yoshida T, Nakamura Y, Sakamoto H. Genome-wide association study of pancreatic cancer in Japanese population. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukuma H, Ajiki W, loka A, Oshima A. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed between 1993 and 1996: a collaborative study of population-based cancer registries in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:602–607. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Epidemiology and risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin Y, Kikuchi S, Tamakoshi A, Yagyu K, Obata Y, Inaba Y, Kurosawa M, Kawamura T, Motohashi Y, Ishibashi T. Obesity, physical activity and the risk of pancreatic cancer in a large Japanese cohort. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2665–2671. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, Dimagno EP, Andren-Sandberg A, Domellof L. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. Pancreatitis the risk of pancreatic cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Body mass index and pancreatic cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1993–1998. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue M, Tajima K, Takezaki T, Hamajima N, Hirose K, Ito H, Tominaga S. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer in Japan: a nested case-control study from the Hospital-based Epidemiologic Research Program at Aichi Cancer Center (HERPACC) Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:257–262. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hruban RH, Canto MI, Goggins M, Schulick R, Klein AP. Update on familial pancreatic cancer. Advances in surgery. 2010;44:293–311. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki H, Li Y, Dong X, Hassan MM, Abbruzzese JL, Li D. Effect of insulin-like growth factor gene polymorphisms alone or in interaction with diabetes on the risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2008;17:3467–3473. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong X, Javle M, Hess KR, Shroff R, Abbruzzese JL, Li D. Insulin-like growth factor axis gene polymorphisms and clinical outcomes in pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:464–473. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.042. 473 e461-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma J, Pollak MN, Giovannucci E, Chan JM, Tao Y, Hennekens CH, Stampfer MJ. Prospective study of colorectal cancer risk in men and plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-binding protein-3. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91:620–625. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.7.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong HL, Delellis K, Probst-Hensch N, Koh WP, Van Den Berg D, Lee HP, Yu MC, Ingles SA. A new single nucleotide polymorphism in the insulin-like growth factor I regulatory region associates with colorectal cancer risk in Singapore Chinese. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2005;14:144–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canzian F, McKay JD, Cleveland RJ, Dossus L, Biessy C, Rinaldi S, Landi S, Boillot C, Monnier S, Chajes V, Clavel-Chapelon F, Tehard B, Chang-Claude J, Linseisen J, Lahmann PH, Pischon T, Trichopoulos D, Trichopoulou A, Zilis D, Palli D, Tumino R, Vineis P, Berrino F, Buenode-Mesquita HB, van Gils CH, Peeters PH, Pera G, Ardanaz E, Chirlaque MD, Quiros JR, Larranaga N, Martinez-Garcia C, Allen NE, Key TJ, Bingham SA, Khaw KT, Slimani N, Norat T, Riboli E, Kaaks R. Polymorphisms of genes coding for insulin-like growth factor 1 and its major binding proteins, circulating levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 and breast cancer risk: results from the EPIC study. British journal of cancer. 2006;94:299–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Zahrani A, Sandhu MS, Luben RN, Thompson D, Baynes C, Pooley KA, Luccarini C, Munday H, Perkins B, Smith P, Pharoah PD, Wareham NJ, Easton DF, Ponder BA, Dunning AM. IGF1 and IGFBP3 tagging polymorphisms are associated with circulating levels of IGF1, IGFBP3 and risk of breast cancer. Human molecular genetics. 2006;15:1–10. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Missmer SA, Haiman CA, Hunter DJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Pollak MN, Hankinson SE. A sequence repeat in the insulin-like growth factor-1 gene and risk of breast cancer. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2002;100:332–336. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng I, Stram DO, Penney KL, Pike M, Le Marchand L, Kolonel LN, Hirschhorn J, Altshuler D, Henderson BE, Freedman ML. Common genetic variation in IGF1 and prostate cancer risk in the Multiethnic Cohort. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:123–134. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez W, Grenade C, Santos ER, Bonilla C, Ahaghotu C, Kittles RA. IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 gene variants influence on serum levels and prostate cancer risk in African-Americans. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2154–2159. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ennishi D, Shitara K, Ito H, Hosono S, Watanabe M, Ito S, Sawaki A, Yatabe Y, Yamao K, Tajima K, Tanimoto M, Tanaka H, Hamajima N, Matsuo K. Association between insulin-like growth factor-1 polymorphisms and stomach cancer risk in a Japanese population. Cancer science. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02062.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergmann U, Funatomi H, Yokoyama M, Beger HG, Korc M. Insulin-like growth factor I over-expression in human pancreatic cancer: evidence for autocrine and paracrine roles. Cancer research. 1995;55:2007–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoeltzing O, Liu W, Reinmuth N, Fan F, Parikh AA, Bucana CD, Evans DB, Semenza GL, Ellis LM. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, vascular endothelial growth factor, and angiogenesis by an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor autocrine loop in human pancreatic cancer. The American journal of pathology. 2003;163:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng H, Datta K, Neid M, Li J, Parangi S, Mukhopadhyay D. Requirement of different signaling pathways mediated by insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor for proliferation, invasion, and VPF/VEGF expression in a pancreatic carcinoma cell line. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2003;302:46–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohmura E, Okada M, Onoda N, Kamiya Y, Murakami H, Tsushima T, Shizume K. Insulin-like growth factor I and transforming growth factor alpha as autocrine growth factors in human pancreatic cancer cell growth. Cancer research. 1990;50:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Minder C, O'Dwyer ST, Shalet SM, Egger M. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3, and cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet. 2004;363:1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamajima N, Matsuo K, Saito T, Hirose K, Inoue M, Takezaki T, Kuroishi T, Tajima K. Gene-environment Interactions and Polymorphism Studies of Cancer Risk in the Hospital-based Epidemiologic Research Program at Aichi Cancer Center II (HERPACC-II) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2001;2:99–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue M, Tajima K, Hirose K, Hamajima N, Takezaki T, Kuroishi T, Tominaga S. Epidemiological features of first-visit outpatients in Japan: comparison with general population and variation by sex, age, and season. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorisson GA, Smith AV, Krishnan L, Stein LD. The International HapMap Project Web site. Genome research. 2005;15:1592–1593. doi: 10.1101/gr.4413105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchenko YV, Carroll RJ, Lin DY, Amos Cl, Gutierrez RG. Semiparametric analysis of case-control genetic data in the presence of environmental factors. Stata Journal. 2008;8:305–333. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamajima N, Yuasa H, Matsuo K, Kurobe Y. Detection of gene-environment interaction by case-only studies. Japanese journal of clinical oncology. 1999;29:490–493. doi: 10.1093/jjco/29.10.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang M, Hu Z, Huang J, Shu Y, Dai J, Jin G, Tang R, Dong J, Chen Y, Xu L, Huang X, Shen H. A 3'-untranslated region polymorphism in IGF1 predicts survival of non-small cell lung cancer in a Chinese population. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:1236–1244. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McElholm AR, McKnight AJ, Patterson CC, Johnston BT, Hardie LI, Murray LI. A population-based study of IGF axis polymorphisms and the esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, adenocarcinoma sequence. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:204–212. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.014. e203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie L, Gong YY, Lian SG, Yang J, Yang Y, Gao SJ, Xu LY, Zhang YP. Absence of association between SNPs in the promoter region of the insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) gene and longevity in the Han Chinese population. Experimental gerontology. 2008;43:962–965. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johansson M, McKay JD, Wiklund F, Rinaldi S, Verheus M, van Gils CH, Hallmans G, Balter K, Adami HO, Gronberg H, Stattin P, Kaaks R. Implications for prostate cancer of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) genetic variation and circulating IGF-I levels. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2007;92:4820–4826. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin Y, Yagyu K, Egawa N, Ueno M, Mori M, Nakao H, Ishii H, Nakamura K, Wakai K, Hosono S, Tamakoshi A, Kikuchi S. An overview of genetic polymorphisms and pancreatic cancer risk in molecular epidemiologic studies. Journal of epidemiology/ Japan Epidemiological Association. 2011;21:2–12. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki T, Matsuo K, Hasegawa Y, Hiraki A, Kawase T, Tanaka H, Tajima K. Anthropometric factors at age 20 years and risk of thyroid cancer. Cancer causes & control: CCC. 2008;19:1233–1242. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]