Abstract

Objective

Psychostimulants are effective treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) but may be associated with euphoric effects, misuse/diversion, and adverse effects. These risks are perceived by some clinicians to be greater in substance-abusing adolescents relative to non–substance-abusing adults. The present study evaluates the subjective effects, misuse/diversion, and adverse effects associated with the use of osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate (OROS-MPH), relative to placebo, for treating ADHD in adolescents with a substance use disorder (SUD) as a function of substance use severity and compared these risks with those associated with the treatment of ADHD in adults without a non-nicotine SUD.

Method

Datasets from two randomized placebo-controlled trials of OROS-MPH for treating ADHD, one conducted with 303 adolescents (13–18) with at least one non-nicotine SUD and one with 255 adult smokers (18–55), were analyzed. Outcome measures included the Massachusetts General Hospital Liking Scale, self-reported medication compliance, pill counts, and adverse events (AEs).

Results

Euphoric effects and misuse/diversion of OROS-MPH were not significantly affected by substance use severity. The euphoric effects of OROS-MPH did not significantly differ between the adolescent and adult samples. Adults rated OROS-MPH as more effective in treating ADHD, whereas adolescents reported feeling more depressed when taking OROS-MPH. The adolescents lost more pills relative to the adults regardless of treatment condition, which suggests the importance of careful medication monitoring. Higher baseline use of alcohol and cannabis was associated with an increased risk of experiencing a treatment-related AE in OROS-MPH, but baseline use did not increase the risk of serious AEs or of any particular category of AE and the adolescents did not experience more treatment-related AEs relative to the adults.

Conclusions

With good monitoring, and in the context of substance abuse treatment, OROS-MPH can be safely used in adolescents with an SUD despite non-abstinence.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which has a prevalence rate of ∼8% in children (Faraone et al. 2003) and 4.4% in adults (Kessler et al. 2006), is characterized by symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity and is associated with significant impairment in functioning, including poorer performance in educational and occupational settings and higher rates of other psychiatric disorders (Spencer et al. 2007). The prevalence of a substance use disorder (SUD) in individuals with ADHD is estimated to be ∼22% in adolescents (Katusic et al. 2005) and 15% in adults (Kessler et al. 2006). Psychostimulants are the mainstay pharmacologic treatment for ADHD. More than 200 randomized, controlled trials (Wilens and Spencer 2000; Schachter et al. 2001) along with decades of clinical experience have established the safety and efficacy of methylphenidate (MPH) preparations in treating ADHD (Greenhill et al. 1999). There is, however, concern about using psychostimulants to treat ADHD in individuals with an SUD (Wilens et al. 2006; Kollins 2008; Levin et al. 2009). These concerns include the possible misuse/diversion of the psychostimulant, increase in the use of the substance that the individual is abusing, and safety concerns arising from interactions between the abused substance and the psychostimulant. Research evaluating the subjective effects, misuse/diversion, and adverse effects associated with the use of psychostimulants in adolescents with ADHD and an SUD is very limited (Riggs et al., submitted for publication). In the absence of such information, the tendency is for clinicians to avoid psychostimulant treatment in adolescents with a current SUD, which is problematic in that adolescents with an SUD and untreated ADHD have poorer substance abuse treatment outcomes (Wise et al. 2001; Whitmore and Riggs 2006).

A National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network (CTN) placebo-controlled trial of osmotic-release oral system (OROS)-MPH was recently completed with adolescent substance abusers with ADHD (Riggs et al., submitted for publication). As reported by Riggs et al. (submitted for publication), results revealed that participants in both treatment arms reduced their substance use and that OROS-MPH was generally well tolerated. More specifically, for the primary outcome measure of self-reported substance use in the past 28 days, the OROS-MPH group had a reduction of 5.7 days and the placebo group had a reduction of 5.2 days. For the present study, secondary analyses were conducted to evaluate the subjective effects, misuse/diversion, tolerability, and adverse events (AEs) associated with the use of OROS-MPH for treating ADHD in adolescents with an SUD as a function of baseline severity of use. In addition, Kollins (2008) noted that possible misuse/diversion of prescription stimulants is of particular concern in young adults, and based on the experience of the present authors, there is an impression among a number of clinicians that there are greater risks associated with psychostimulant treatment in adolescents with an SUD relative to adults without an SUD. Thus, we compared measures of subjective effects, misuse/diversion, tolerability, and AEs in the adolescents with those of adults with ADHD with no current non-nicotine SUD. The adult data for these comparisons came from a recently completed NIDA CTN placebo-controlled trial of OROS-MPH for adult smokers with ADHD, which found that both the OROS-MPH and placebo groups significantly decreased their cigarettes per day (CPD) with a statistically significant greater decrease in the OROS-MPH group, relative to placebo (Winhusen et al. 2010). This comparison group of adults was specifically selected for two reasons. First, both SUD, other than nicotine dependence, and antisocial personality disorder were exclusionary in the adult study, and thus, misuse/diversion in the adult sample could be expected to be minimal, providing a “gold standard” against which to compare the adolescents. Second, the adolescent and adult studies were largely parallel, utilizing identical OROS-MPH/placebo dosing regimens and assessments. The primary differences between the two studies were the length of the active treatment phase (16 weeks in the adolescent and 11 weeks in the adult studies), the background psychosocial treatment (1 hour weekly cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT] in the adolescent and 10-minute weekly behavioral smoking cessation counseling in the adult studies), and the provision of nicotine patches in the adult study.

The subjective effects of OROS-MPH in adolescents with an SUD have not been reported in the literature. Laboratory studies completed with normal adults (Spencer et al. 2006) and adults with a history of recreational stimulant use (Parasrampuria et al. 2007) suggest that positive subjective effects, which are considered indicators of abuse liability, are significantly lower for OROS-MPH compared with immediate release (IR)-MPH. Laboratory double-blind choice procedure and self-administration studies of IR-MPH in children and adults with ADHD suggest that although individuals with ADHD choose IR-MPH more than placebo, this selection is related to the therapeutic, rather than the euphoric, effects of the medication (Fredericks and Kollins 2004, 2005; Kollins et al. 2009). Given the generally low abuse liability of OROS-MPH, it was predicted that the euphoric subjective effects of OROS-MPH would not differ significantly from those of placebo and would not differ as a function of baseline substance use severity and that adolescent ratings would not significantly differ from adult ratings.

Research suggests that misuse/diversion of psychostimulants by adolescents and young adults is less for long-acting, relative to IR, formulations (Wilens et al. 2008). For the present analyses, it was predicted that the measures of misuse/diversion (e.g., taking more than prescribed and losing pills) would not significantly differ as a function of treatment group in the adolescents with an SUD or as a function of baseline use severity. It was also predicted that the adolescents would not significantly differ from the adults on possible OROS-MPH misuse/diversion. In adolescents with ADHD and an SUD, potential interactions between OROS-MPH and drugs of abuse are of concern to treatment providers. The safety data reported by Riggs et al. (submitted for publication) revealed that OROS-MPH was well tolerated and that the reported side-effects were consistent with the known side-effects profile of OROS-MPH. For the present analyses, it was predicted that there would not be a treatment by substance use severity interaction for the occurrence of treatment-related AEs. It was also predicted that the adolescents would not experience significantly greater treatment-related AEs relative to the adults.

Methods

Participants

The participants for the ADHD and SUD study were 303 adolescents (aged 13–18 years) recruited by 11 participating substance abuse treatment programs affiliated with the NIDA CTN. Criteria for study participation included meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association 1994) diagnostic criteria for current ADHD and at least one non-tobacco SUD. Exclusion criteria were current or past psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, suicide risk, opiate dependence, methamphetamine abuse or dependence, cardiac illness or serious medical illness, pregnancy, past month use of psychotropic medications or participation in other substance, or mental health treatment. The participants for the ADHD smoking study were 255 adults (aged 18–55 years) recruited by six participating sites affiliated with the NIDA CTN. Criteria for study participation included meeting DSM-IV criteria for current ADHD, smoking at least 10 CPD, having a carbon monoxide level ≥8 ppm, and being interested in quitting smoking. Exclusion criteria included high blood pressure, cardiac illness, serious medical illness, medication or a condition for which OROS-MPH is contraindicated, pregnancy, a positive urine screen for an illicit drug, or meeting DSM-IV criteria for the following parameters: Current abuse or dependence for any psychoactive substance other than nicotine, current major depression, any anxiety disorder except specific phobias, antisocial personality disorder, or a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or psychosis. Participants in both studies were required to have a DSM-IV ADHD Rating Scale, (ADHD-RS) (DuPaul et al. 1998) total score of >22. All participants were given a thorough explanation of the study and signed an informed consent form that was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating sites (trial registration: clinical trials.gov; www.clinicaltrials.gov; identifiers: NCT00253747, NCT00264797).

Procedures

See the papers by Riggs et al. (submitted for publication) and Winhusen et al. (2010) for a full description of procedures for the adolescent and adult studies, respectively. In both studies, participants were randomized to OROS-MPH or matching placebo in a 1:1 ratio, stratified by site, and completed by computer at a centralized location. For OROS-MPH, the starting dose of 18 mg/day was escalated during the first 2 study weeks to a maximum of 72 mg/day or to the highest dose tolerated. In both studies, participants were given enough medication for 2 weeks to help ensure continuity of treatment if the participant was unable to attend a given study week. The adolescent ADHD study included a 16-week active treatment phase during which participants took OROS-MPH or placebo and were scheduled for weekly 1-hour individual CBT sessions targeting substance abuse. The adult ADHD study included an 11-week active treatment phase during which participants took OROS-MPH or placebo and were scheduled for weekly 10-minute individual smoking cessation counseling sessions. All participants in the adult ADHD study received transdermal nicotine patches (Habitrol; Novartis, Parsippany, NJ) and were instructed to wear a 21-mg patch daily beginning on the target quit date (study day 27) through week 11.

Measures

Subjective effects were assessed with the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Liking Scale, which is a derivative of the ARCI Benzedrine scales (Martin et al. 1971) and was developed by Wilens and colleagues to evaluate the likeability of a medication while disentangling the therapeutic effects of the medication from the euphoria scales (e.g., ratings of high and liking), an important confound for individuals with ADHD as articulated by Fredericks and Kollins (2004). Although the MGH Liking Scale has not been validated, it was selected for use because there were no psychometrically validated scales available that assessed subjective effects, including likeability, while also accounting for the impact that therapeutic effects can have on likeability. The assessment included six items, each rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very much), concerning the impact of the medication on the participant: Effectiveness in treating ADHD, medication liking, feeling high/euphoric, feeling depressed/down, craving the medication, and craving cigarettes, alcohol, or other nonprescribed drugs. The MGH Liking Scale was completed at study weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16 (end of treatment) in the adolescent study and at study weeks 4 and 11 (end of treatment) in the adult study. The week 4 MGH Liking Scale assessment from the adult and adolescent studies and the weeks 11 and 12 assessments from the adult and adolescent studies, respectively, were utilized to compare the relative subjective effects of OROS-MPH in the adolescents and adults.

As noted by Kollins (2008), there are several clinical indicators of potential misuse/diversion of medication including reported lost pills, requesting higher doses, and requesting replacement medication. Pill count and self-report of medication compliance, including information about lost pills, replacement bottles being dispensed, and cases of participants taking more than the prescribed 72 mg/day, were obtained in both the adolescent and adult studies on a weekly basis during the active treatment phase. In both studies, AEs were assessed on a weekly basis during the active treatment phase by asking the participant how he or she had been feeling since the last visit. Treatment-relatedness was determined by the medical clinician, with each AE rated as definitely related, probably related, possibly related, or unrelated; any rating other than unrelated was classified as a treatment-related AE. For the adolescent analyses, substance use severity was defined as the proportion of days on which substances were used during the 28 days prior to consent assessed using standard timeline follow-back procedures (Sobell and Sobell 1992). This included the baseline severity of alcohol use, cannabis use, tobacco use, and illicit drugs other than cannabis use.

Data analysis

All statistical tests were conducted at the 5% type I error rate (two-sided). Two sets of regressions were performed on intent-to-treat samples using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). One set of regressions used the combined results from the studies involving adult smokers and adolescents with SUD. For each measure, a regression tested the significance of treatment (OROS-MPH vs. placebo), study, and when included, treatment by study interaction. Within-study regressions were also performed for each measure testing the significance of treatment. For each measure, the corrected Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) criterion determined the inclusion of the treatment by study interaction as well as the inclusion of the covariates on which the adult and adolescent samples significantly differed: Gender, race, Hispanic (yes/no), baseline ADHD-RS score, and duration of treatment phase participation.

The second set of regressions involved only the adolescents with SUD. Outcomes were regressed against treatment and substance use severity for each of several substance classes where level of use was indicated by the proportion of self-reported use days in the 28 days prior to screening. For summary purposes, the median proportion days of use was used to categorize the adolescents into two severity groups (i.e., above and on-or-below median use); however, the regressions, themselves, used the raw proportions. For each measure and substance class, a single regression was performed testing the significance of treatment, baseline substance use, and when indicated by the corrected AIC criterion, the treatment by substance use severity interaction.

The measure being regressed determined the type of regression used for each evaluation. Yes/no participant indicators (such as whether or not a participant reported a given type of AE) were evaluated using logistic regressions. Within-participant binomial counts were evaluated using logistic regressions with random intercepts. The remaining measures were evaluated using normal regressions where random intercepts were used for measures that were replicated within participant. In all regressions, significance for each covariate of interest was tested at the 0.05 level using a Wald chi-square test.

Results

Sample characteristics

The characteristics of the adolescent and adult study samples are provided in Table 1. There were no significant differences between treatment groups within each study and no study by treatment group interactions (data not shown). As can be seen, there were several differences between the study samples, including more males and more minorities in the adolescent study, relative to the adult study. In addition, the baseline ADHD severity score in the adolescents was higher than that of the adults. Because of the difference in exclusion criteria between the two studies, the adolescents also had a greater rate of co-occurring disorders, with 32.3% of the adolescents meeting criteria for conduct disorder and 12.5% meeting criteria for major depressive disorder.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic and Baseline Characteristics as a Function of Study

| Adolescents with SUD (n=303) | Adult smokers (n=255) | Between study analysis χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 16.5 (1.3) | 37.8 (10.0) | 1352.5a |

| Sex (% male) | 78.9 | 56.5 | 31.3a |

| Race (%) | 9.0b | ||

| African-American | 23.2 | 5.9 | |

| Caucasian | 61.7 | 82.6 | |

| Asian | 1.3 | 1.6 | |

| Native American/Alaskan | 1.0 | 0.4 | |

| Other | 6.0 | 4.0 | |

| Mixed race | 6.7 | 5.5 | |

| Hispanic (%) | 15.2 | 7.1 | 8.6b |

| DSM-IV ADHD-RS total score | 38.7 (8.9) | 36.4 (7.3) | 11.6a |

| ADHD subtype (%) | 3.02 | ||

| Inattentive | 28.2 | 34.3 | |

| Hyperactive-impulsive | 2.7 | 3.9 | |

| Combined | 69.1 | 61.8 |

Where not specifically indicated, numbers represent means (standard deviations).

p<0.001.

p<0.01.

ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SUD=substance use disorder; ADHD-RS=DSM-IV ADHD Rating Scale.

Adolescent substance use severity

This section presents the results from the evaluation of the subjective effects, misuse/diversion, and adverse effects associated with the use of OROS-MPH, relative to placebo, for treating ADHD in adolescents with an SUD as a function of baseline substance use severity.

Baseline substance use severity

Baseline use, as a function of substance, for the 303 adolescents is provided in Table 2. As can be seen by the median proportion days of use, the adolescents reported greater use of cannabis and tobacco relative to alcohol or other illicit drugs, with the use of other illicit drugs reported by few adolescents.

Table 2.

Baseline Substance Use Severity as a Function of Substance in Adolescent Sample

| Alcohol | Cannabis | Tobacco | Other drug | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median days of use per 28 days | 1.0 | 11.0 | 24.0 | 0.0 |

| Mean days of use by participants <median | 0.37 (0.49) | 4.47 (3.81) | 5.73 (7.86) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Mean days of use by participants ≥median | 5.72 (4.77) | 21.89 (5.89) | 27.74 (0.65) | 4.10 (5.01) |

Subjective effects as a function of treatment and substance use severity

For the adolescents, there were significant treatment effects for three of the six MGH Liking Scales, all of which reflected higher ratings by the OROS-MPH group, relative to placebo: Effectiveness in treating ADHD [χ2(1)=17.33, p<0.0001], feeling high [χ2(1)=13.42, p<0.001], and feeling depressed [χ2(1)=8.38, p<0.01]. There were no significant treatment effects for the remaining three scales: Liking how the medication makes you feel [χ2(1)=1.66, p=0.20], craving the medication [χ2(1)=1.78, p=0.18], and craving substances [χ2(1)=3.48, p=0.06]. By-substance analyses regressing MGH scale measures against substance use severity, treatment, and treatment by use severity interaction effects revealed no significant use severity main effect for any of the regressions and only one treatment by use severity interaction effect, which was for tobacco for feeling depressed [χ2(1)=4.3, p<0.05], with adolescents above the median of use experiencing more depressed mood with OROS-MPH, relative to placebo.

Misuse/diversion as a function of treatment and substance use severity

The regressions for the misuse/diversion measures revealed no significant treatment, substance use severity, or treatment by substance use severity interactions (data not shown), suggesting that potential misuse/diversion did not significantly differ between the OROS-MPH and placebo groups or as a function of substance use severity.

Medication tolerability as a function of treatment and substance use severity

The regressions for the medication tolerability measures revealed no significant treatment, or treatment by substance use severity interactions (data not shown), suggesting that medication tolerability did not differ significantly between the OROS-MPH and placebo group participants and that substance use severity was not associated with the tolerability of OROS-MPH. There was one significant substance use severity effect, which was for alcohol use [χ2(1)=5.6, p<0.05], for the maximum medication dose reached, with adolescents below the median of baseline alcohol use reaching a higher medication dose (mean=71.4, SD=10.0) relative to adolescents above the median baseline alcohol use (mean=69.9, SD=12.3), regardless of treatment condition.

Treatment-related AEs as a function of treatment and substance use severity

The regressions for treatment-related AEs in general revealed a significant treatment by substance use severity interaction for alcohol use [χ2(1)=5.3, p<0.05] and cannabis use [χ2(1)=5.3, p<0.05], with adolescents above the baseline median of use being more likely to experience a treatment-related AE in the OROS-MPH condition, relative to placebo; this interaction was not significant for tobacco or other illicit drug use. Analyses of the treatment-related AEs by body system revealed a significant treatment by use severity interaction for only one substance, alcohol, and for only one body system, gastrointestinal disorders. Review of the data (not shown) revealed that the occurrence of gastrointestinal disorders in the OROS-MPH group, relative to placebo, was actually higher in the adolescents whose proportion of alcohol use days was less than the median. As noted above, adolescents using more alcohol than the baseline median had a lower medication dose, which could account for the observed lower level of gastrointestinal disorders. Analyses of serious AEs (SAEs) and treatment-related SAEs revealed no significant treatment effect or treatment by baseline substance use interaction. The results from these analyses suggest that relatively higher levels of alcohol and cannabis use were related to a greater probability of treatment-related AEs from OROS-MPH but that there was not an increased risk of any particular category of AE and there was no increased risk of SAEs.

Comparisons of adolescents with an SUD and adult smokers

This section presents the results from the analyses evaluating the subjective effects, misuse/diversion, and adverse effects associated with the use of OROS-MPH, relative to placebo, for treating ADHD in adolescents with an SUD compared with adults without a nonnicotine SUD.

Subjective effects as a function of treatment and study sample

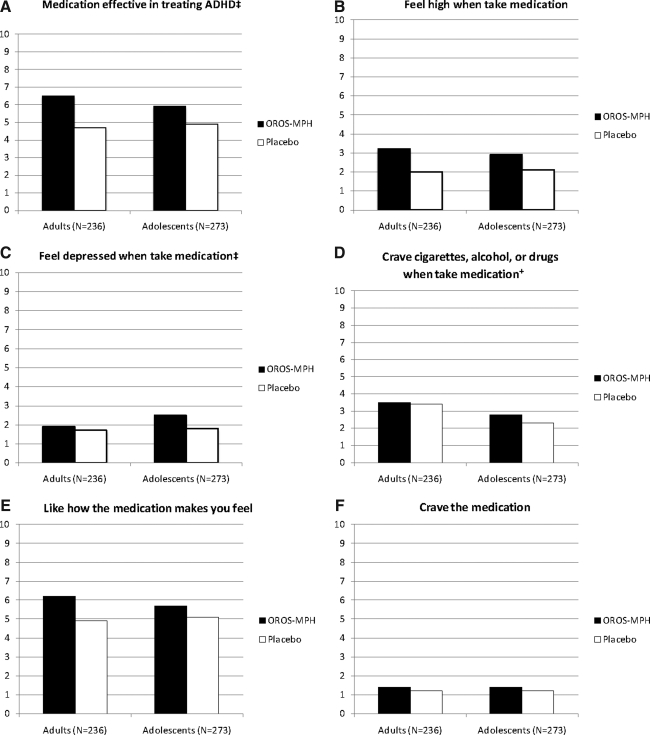

Average MGH Liking Scale ratings as a function of treatment and study sample are displayed in Figure 1. There were significant treatment by study interaction effects for two of the six scales: Effectiveness in treating ADHD [χ2(1)=6.7, p<0.01] and feeling depressed [χ2(1)=4.4, p<0.05]. As can be seen in Figure 1, OROS-MPH was rated as more effective than placebo in treating ADHD by the adults than by the adolescents. As can also be seen, the significant treatment by study interaction effect for feeling depressed reflected a greater rating of depressed mood by adolescents in the OROS-MPH group, relative to placebo, an effect not seen in the adults. There were no significant treatment by study interaction effects for the remaining four scales: Feeling high [χ2(1)=2.0, p=0.16]; liking how the medication makes you feel [χ2(1)=0.6, p=0.44]; craving substances [χ2(1)=0.6, p=0.45]; and for craving the medication, the treatment by study interaction was not included in the regressions. There was a significant study effect for one scale: Craving substances [χ2(1)=14.2, p<0.001]. As can be seen in Figure 1, the adults reported greater craving for substances, most likely cigarettes, relative to the adolescents and regardless of treatment condition.

FIG. 1.

Mean Massachusetts General Hospital Liking Scale ratings as a function of treatment and study sample. †Significant study effect, p<0.05; ‡Significant treatment by study interaction, p<0.05. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; OROS-MPH, osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate.

To evaluate whether medication liking was more closely associated with feeling high or with the perceived effectiveness of the medication in treating ADHD, liking was correlated with effectiveness and with feeling high using Pearson r. These correlations were separately done for these measures for the adolescent and adult samples. For the adolescents, medication liking significantly correlated with medication high (r=0.29, p<0.0001) but had an even greater correlation with medication effectiveness (r=0.55, p<0.0001). A similar result was seen for the adults, with medication liking significantly correlating with medication high (r=0.33, p<0.0001) but more strongly correlating with medication effectiveness (r=0.78, p<0.0001).

Misuse/diversion as a function of treatment and study sample

The misuse/diversion measures as a function of treatment group and study sample are provided in Table 3. As can be seen, there were no significant treatment group differences in the adolescents or adults on these measures, suggesting no significant misuse/diversion of OROS-MPH. As can be seen in Table 3, there were significant study effects for the proportion of participants reporting lost pills, the number of pills lost, and the number of pills not returned, which reflected a greater incidence of these events in the adolescents, relative to the adults, regardless of treatment condition, which suggests that the adolescents were more prone to losing pills relative to the adults but that this was not specific to OROS-MPH. As can be seen in Table 3, the average number of pills lost by the adolescents equates to ∼3 days of dosing. It should be noted that this difference is probably not attributable to ADHD severity, because the AIC process did not find ADHD severity as a contributing factor in any of the regressions.

Table 3.

Potential Misuse/Diversion as a Function of Treatment Condition and Study Sample

| |

Adolescents with an SUD |

Adult smokers |

Adolescents vs. adults |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OROS-MPH (n=151) | Placebo (n=152) | Treatment analysis χ2 | OROS-MPH (n=127) | Placebo (n=128) | Treatment analysis χ2 | Between study analysis χ2 | Treatment by study analysisa χ2 | |

| Took >72 mg/day | 2.7% | 1.3% | 0.5 | 1.6% | 0.8% | 0.3 | 0.2 | — |

| Days took >72 mg/dayb | 1.5 (1.0) | 3.5 (3.5) | 0.3 | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.0) | — | 2.4 | — |

| Reported lost pills | 43.0% | 43.6% | 0.1 | 16.1% | 20.6% | 0.9 | 16.4c | — |

| Number of pills lostd | 12.1 (16.6) | 11.0 (14.9) | 0.2 | 5.1 (7.2) | 5.8 (7.4) | 0.3 | 9.5e | — |

| Returned <expected pills | 24.8% | 21.5% | 0.5 | 21.0% | 27.0% | 0.6 | 0.5 | — |

| Pills not returnedf | 15.1 (20.8) | 13.1 (13.0) | 0.5 | 12.4 (12.5) | 9.7 (10.3) | 2.4 | 4.5g | 2.5 |

| Medication replaced | 14.8% | 11.4% | 0.3 | 3.2% | 4.0% | 0.1 | 0.4 | — |

| Bottles replacedh | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.0 | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.0 | 0.0 | — |

Where not specifically indicated, numbers represent means (standard deviations).

Treatment by study interaction is left blank as its inclusion was not determined by Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) assessment to contribute to the analysis.

Mean number of excess pills taken by participants reporting taking >72 mg (four pills).

p<0.001.

Mean number of pills lost by participants reporting losing pills.

p<0.01.

Mean number of pills not returned by participants returning fewer pills than expected.

p<0.05.

Mean number of bottles replaced by participants having a bottle replaced.

OROS-MPH = osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate.

Medication tolerability as a function of treatment and study sample

A comparison of medication tolerability between the adolescents and adults as measured by maximum dose, sustained dose, permanent dose reduction, and discontinued medication revealed no significant treatment by study interaction (Table 4), which suggests that the ability to tolerate OROS-MPH did not significantly differ between the adolescents and adults. As can be seen in Table 4, there was a significant study effect for maximum dose reached, and proportion with a permanent dose reduction, reflecting lower tolerability in the adults, regardless of treatment arm, relative to the adolescents, which might be due to the adults receiving the nicotine patch in addition to OROS-MPH.

Table 4.

Medication Tolerability and Treatment-Related Adverse Events as a Function of Treatment Condition and Study Sample

| |

Adolescents with an SUD |

Adult smokers |

Adolescents vs. adults |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OROS-MPH (n=151) | Placebo (n=152) | Treatment analysis χ2 | OROS-MPH (n=127) | Placebo (n=128) | Treatment analysis χ2 | Between study analysis χ2 | Treatment by study analysisa χ2 | |

| Maximum dose reached | 70.2 (13.0) | 71.1 (9.0) | 1.1 | 69.7 (13.7) | 69.3 (10.2) | 0.0 | 5.2b | 1.5 |

| Sustained dose | 67.0 (14.9) | 68.0 (14.7) | 0.2 | 62.0 (19.0) | 64.0 (19.3) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Permanent dose reduction | 10.7% | 6.8% | 1.1 | 19.8% | 13.5% | 1.9 | 10.6c | — |

| Medication discontinued | 4.6% | 7.2% | 1.8 | 16.5% | 11.7% | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.6 |

| SAEs | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.6) | 2.1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 | — |

| AEs | 111 (73.5) | 98 (64.5) | 1.6 | 111 (87.4) | 95 (74.2) | 6.7c | 20.2d | — |

| AEs by body system,en (%) | ||||||||

| Cardiac | 6 (4.0%) | 3 (2.0%) | 1.0 | 9 (7.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 3.9b | 0.7 | — |

| Gastrointestinal | 31 (20.5%) | 29 (19.1%) | 0.1 | 43 (33.9%) | 22 (17.2%) | 9.2c | 0.1 | 4.4b |

| Investigationsf | 14 (9.3%) | 5 (3.3%) | 3.7 | 17 (13.4%) | 3 (2.3%) | 8.6c | 3.5 | — |

| Metabolism/nutrition | 32 (21.2%) | 8 (5.3%) | 13.7c | 28 (22.1%) | 5 (3.9%) | 15.1c | 0.2 | — |

| Nervous system disorder | 56 (37.1%) | 51 (33.6%) | 0.2 | 52 (40.9%) | 35 (27.3%) | 5.7b | 0.6 | 2.4 |

| Psychiatric | 37 (24.5%) | 30 (19.7%) | 0.8 | 78 (61.4%) | 62 (48.4%) | 4.3b | 53.9c | — |

Where not specifically indicated, numbers represent means (standard deviations).

Treatment by study interaction is left blank as its inclusion was not determined by Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) assessment to contribute to the analysis.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

p<0.001.

AEs by body system for which an event was reported by >5% of the OROS-MPH group and at a greater rate than by the placebo group in at least one study sample.

Investigations are AEs identified through study procedures (e.g., vital signs readings).

AE=adverse event; SAE=serious adverse event.

Treatment-related AEs as a function of treatment and study sample

As reported by Riggs et al. (submitted for publication) and Winhusen et al. (2010), OROS-MPH participants experienced significantly more AEs than placebo participants in both the adolescent and adult studies, respectively. To evaluate the relative risk of AEs in adolescent substance abusers, we compared the overall rates of treatment-related SAEs, AEs, and AEs by body system. As can be seen in Table 4, there was a significant treatment by study interaction effect for gastrointestinal AEs, reflecting a greater occurrence of these AEs in OROS-MPH, relative to placebo, in the adults compared with the adolescents. The significant study effect for treatment-related AEs and for psychiatric AEs reflects the greater occurrence of these events in the adults, relative to the adolescents, regardless of treatment arm.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the subjective effects, misuse/diversion, and treatment-related AEs associated with the use of OROS-MPH, relative to placebo, for treating ADHD in adolescents with an SUD as a function of substance use severity and compared these risks with those associated with the treatment of adults with no SUD other than nicotine addiction. The results suggest that the euphoric effects of OROS-MPH were not significantly affected by substance use severity and did not significantly differ between the adolescent and adult samples. The two medication rating scales for which there were treatment by study interaction effects were the effectiveness of the medication in treating ADHD, for which OROS-MPH was rated higher than placebo by the adults relative to the adolescents, and feeling depressed when taking the medication, for which OROS-MPH was rated higher than placebo by the adolescents relative to the adults. The higher rating of OROS-MPH effectiveness by the adults is consistent with the main outcome findings in that a significant OROS-MPH effect was found for ADHD symptom reduction in the adult study (Winhusen et al. 2010) but not in the adolescent study (Riggs et al., submitted for publication). The greater rating of feeling depressed by the adolescents, while statistically significant, was a small effect (i.e., average rating of 2.5 for OROS-MPH compared with 1.8 for placebo on a 10-point scale) and unlikely to be clinically significant. Still, increased depressed mood in the adolescents suggests that clinicians should be alert to a possible increase in depressed mood when treating adolescents with ADHD and an SUD, a population that has a high rate of co-occurring disorders (e.g., conduct disorder and major depressive disorder). Past research suggests that the positive subjective effect of OROS-MPH is lower relative to IR-MPH (Spencer et al. 2006; Parasrampuria et al. 2007). The present study found that both adults and adolescents rated OROS-MPH as being associated with a greater medication high compared with placebo, whereas the average rating was only one point higher for OROS-MPH compared with placebo and thus is of questionable clinical significance; the finding suggests that there may be some potential for abuse. Previous research has found that the likeability of psychostimulants in individuals with ADHD is associated more with therapeutic effect than with euphoric effects (Fredericks and Kollins 2004 2005; Kollins et al. 2009). Results from the present analyses are consistent with this research in that the correlation between medication liking and treatment effectiveness was stronger than the correlation between liking and high for both the adolescent and adult samples.

For adolescent misuse/diversion of OROS-MPH, the results suggest that OROS-MPH was not misused/diverted more than placebo and was not impacted by baseline substance use severity. Significantly more adolescents lost pills, relative to the adults, regardless of treatment condition, which might indicate a greater likelihood for adolescents to misuse/divert their medication or might simply reflect greater carelessness on the part of the adolescents. In either case, the greater loss of pills by the adolescents suggests that, as noted by Kollins (2008), effectively treating this population likely entails close monitoring. Medication dosing and AEs revealed that both the adults and adolescents generally tolerated OROS-MPH well, with the adolescents having significantly fewer individuals with a permanent dose reduction and a higher sustained dose than the adults regardless of treatment condition, which may reflect differences in metabolism between the age groups, the fact that the adults received nicotine patch in addition to OROS-MPH/placebo, or the better general health of the adolescents. The tolerability of OROS-MPH, relative to placebo, was not significantly impacted by baseline substance use severity in the adolescents. However, higher baseline use of alcohol and cannabis was associated with an increased risk of experiencing a treatment-related AE in OROS-MPH, relative to placebo, which suggests the need to monitor side-effects closely in substance abusing adolescents. Still, baseline use did not increase the risk of SAEs or of any particular category of AE and the adolescents did not experience more treatment-related AEs relative to the adults. Rather, the adults were more likely than the adolescents to have gastrointestinal AEs in response to OROS-MPH and also experienced more AEs, regardless of treatment arm, compared with the adolescents.

The present results should be considered in conjunction with several limitations. First, the amount of monitoring provided in the clinical trials, which included weekly monitoring and dispensing of study medication, was much more intensive than the monitoring typically provided in clinical practice. Thus, the findings related to potential misuse/diversion may not generalize to clinical practice. Second, the adolescents received 1 hour of substance abuse treatment each week, in the form of CBT, and this treatment may have served to reduce the likelihood of medication misuse or diversion. Third, the data for these analyses were collected for clinical trials not specifically designed to evaluate the relative risks of OROS-MPH as a function of substance use severity or to compare the risks in adolescent and adult samples. Thus, the results should be considered in light of the exploratory nature of the analyses. In addition, there is no psychometrically validated instrument that assesses the subjective effects of a medication, including likeability, while also accounting for the impact that therapeutic effects can have on likeability, and thus, we utilized the MGH Liking Scale, an instrument that has not been yet validated. Finally, the present results are based on a 4-month active treatment phase, and thus, effects associated with taking OROS-MPH over a longer period of time were not assessed. The present study also has several strengths, including the large sample size and the relative comparability of the adolescent and adult trials, which were designed and managed by an overlapping group of investigators. Moreover, given that ∼22% of adolescents with ADHD have an SUD (Katusic et al. 2005) and the relative dearth of research evaluating the risks of OROS-MPH treatment in adolescents with an SUD, this study helps to address an important gap in the literature.

Conclusions

In summary, the risks of using OROS-MPH to treat ADHD in substance-abusing adolescents are perceived by some clinicians to be greater than the risks associated with treating non–substance-abusing adults. The present analyses suggest that euphoric subjective effects and adverse effects that may be associated with OROS-MPH are not greater in adolescents with an SUD relative to adults with no SUD other than nicotine addiction. In addition, baseline substance use severity in the adolescents was not associated with subjective effects or misuse/diversion of OROS-MPH but was associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing a treatment-related AE. Significantly more adolescents lost pills, relative to the adults, regardless of treatment condition, which suggests the need for close monitoring; such monitoring is consistent with the requirements of prescribing OROS-MPH, which is a Schedule II medication.

Clinical Significance

Research evaluating the subjective effects, misuse/diversion, and adverse effects associated with the use of psychostimulants in adolescents with ADHD and an SUD is very limited (Riggs et al., submitted for publication). In the absence of such information, the tendency is for clinicians to avoid psychostimulant treatment in adolescents with a current SUD, which is problematic in that adolescents with an SUD and untreated ADHD have poorer substance abuse treatment outcomes (Wise et al. 2001; Whitmore and Riggs 2006). The present results suggest that, with careful monitoring and in the context of substance abuse treatment, OROS-MPH can be safely used in adolescents with an SUD despite nonabstinence and that the associated risks are not greater than those associated with treating adults without an SUD.

Disclosures

Dr. Adler reported being a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Cortex Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Shire, Eli Lilly, Ortho McNeil/Jannsen/Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Organon, Sanofi-Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Psychogenics, Mindsite-uncompensated, AstraZeneca, Major League Baseball, i3 Research, Epi-Q, INC Research, United Biosource, Otsuka, Major League Baseball Players Association; receiving grant support from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck & Co., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Shire, Eli Lilly, Ortho McNeil/Jannsen/Johnson and Johnson, New River Pharmaceuticals, Cephalon, NIDA, Chelsea Therapeutics, Organon.; being on the Advisory Board for Abbott Laboratories Cortex Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Shire, Eli Lilly, Ortho McNeil/Jannsen/Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Organon, Sanofi-Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Psychogenics, Mindsite-uncompensated, AstraZeneca Major League Baseball, i3 Research; being on Speaker's Bureaus for Shire, Eli Lilly, Ortho McNeil/Jannsen/Johnson and Johnson, (have not participated in speaker's bureaus for over a year); and receiving royalty payments (as inventor) from NYU for license of adult ADHD scales and training materials. Dr. Davies served on speaker's bureaus for Eli Lilly and Pfizer during the active phase of this study, although he has no affiliation with either company in >2 years. Dr. Sonne reported receiving grant support from Forest Laboratories. The remaining authors reported no financial disclosures.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, editor; Power TJ, editor; Anastopoulos AD, editor; Reid R, editor. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, Clinical Interpretation. New York: The Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV. Sergeant J. Gillberg C. Biederman J. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: Is it an American condition? World Psychiatry. 2003;2:104–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks EM. Kollins SH. A pilot study of methylphenidate preference assessment in children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:729–741. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks EM. Kollins SH. Assessing methylphenidate preference in ADHD patients using a choice procedure. Psychopharmacology. 2004;175:391–398. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill LL. Halperin JM. Abikoff H. Stimulant medications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:503–512. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199905000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katusic SK. Barbaresi WJ. Colligan RC. Weaver AL. Leibson CL. Jacobsen SJ. Psychostimulant treatment and risk for substance abuse among young adults with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A population-based, birth cohort study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:764–776. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Adler L. Barkley R. Biederman J. Conners CK. Demler O. Faraone SV. Greenhill LL. Howes MJ. Secnik K. Spencer T. Ustun TB. Walters EE. Zaslavsky AM. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:716–723. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins SH. ADHD, substance use disorders, and psychostimulant treatment: Current literature and treatment guidelines. J Atten Disord. 2008;12:115–125. doi: 10.1177/1087054707311654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins SH. English J. Robinson R. Hallyburton M. Chrisman AK. Reinforcing and subjective effects of methylphenidate in adults with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:73–83. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1439-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin FR. Mariani JJ. Secora A. Brooks D. Cheng WY. Bisaga A. Nunes E. Aharonovich E. Raby W. Hennessy G. Atomoxetine treatment for cocaine abuse and adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A preliminary open trial. J Dual Diagn. 2009;5:41–56. doi: 10.1080/15504260802628767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR. Sloan JW. Sapira JD. Jasinski DR. Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1971;12:245–258. doi: 10.1002/cpt1971122part1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasrampuria DA. Schoedel KA. Schuller R. Silber SA. Ciccone PE. Gu J. Sellers EM. Do formulation differences alter abuse liability of methylphenidate? A placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, crossover study in recreational drug users. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:459–467. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e3181515205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter HM. Pham B. King J. Langford S. Moher D. How efficacious and safe is short-acting methylphenidate for the treatment of attention-deficit disorder in children and adolescents? A meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2001;165:1475–1488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC. Sobell MD. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R.Z., editor; Allen J.P., editor. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ. Biederman J. Ciccone PE. Madras BK. Dougherty DD. Bonab AA. Livni E. Parasrampuria DA. Fischman AJ. PET study examining pharmacokinetics, detection and likeability, and dopamine transporter receptor occupancy of short- and long-acting oral methylphenidate. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:387–395. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ. Biederman J. Mick E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:631–642. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore EA. Riggs PD. Developmentally informed diagnostic and treatment considerations in comorbid conditions. In: Liddle H.A., editor; Rowe C.L., editor. Adolescent Substance Abuse: Research and Clinical Advances. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 264–283. [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE. Adler LA. Adams J. Sgambati S. Rotrosen J. Sawtelle R. Utzinger L. Fusillo S. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: A systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:21–31. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE. Gignac M. Swezey A. Monuteaux MC. Biederman J. Characteristics of adolescents and young adults with ADHD who divert or misuse their prescribed medications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:408–414. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000199027.68828.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE. Spencer TJ. The stimulants revisited. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2000;9:573–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen TM. Somoza EC. Brigham GS. Liu DS. Green CA. Covey LS. Croghan IT. Adler LA. Weiss RD. Leimberger JD. Lewis DF. Dorer EM. Impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatment on smoking cessation intervention in ADHD smokers: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1680–1688. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05089gry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise BK. Cuffe SP. Fischer T. Dual diagnosis and successful participation of adolescents in substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]