Abstract

ATP-binding cassette protein A1 (ABCA1) plays a major role in cholesterol homeostasis and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) metabolism. Although it is predicted that apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) directly binds to ABCA1, the physiological importance of this interaction is still controversial and the conformation required for apoA-I binding is unclear. In this study, the role of the two nucleotide-binding domains (NBD) of ABCA1 in apoA-I binding was determined by inserting a TEV protease recognition sequence in the linker region of ABCA1. Analyses of ATP binding and occlusion to wild-type ABCA1 and various NBD mutants revealed that ATP binds equally to both NBDs and is hydrolyzed at both NBDs. The interaction with apoA-I and the apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux required not only ATP binding but also hydrolysis in both NBDs. NBD mutations and cellular ATP depletion decreased the accessibility of antibodies to a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope that was inserted at position 443 in the extracellular domain (ECD), suggesting that the conformation of ECDs is altered by ATP hydrolysis at both NBDs. These results suggest that ATP hydrolysis at both NBDs induces conformational changes in the ECDs, which are associated with apoA-I binding and cholesterol efflux.

Keywords: ATP binding cassette protein A1, apolipoproteins, cholesterol efflux, HDL, transport

Cholesterol is an essential component of cellular membranes, but excess cholesterol accumulation is harmful to cells. Therefore, cellular cholesterol levels are extensively regulated by various mechanisms (1, 2). Mutations in the ATP binding cassette protein A1 (ABCA1) gene lead to Tangier disease, which is characterized by an accumulation of excess cellular cholesterol and low plasma high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (3–5). The link between the ABCA1 gene and Tangier disease indicates that ABCA1 plays a pivotal role in cholesterol homeostasis by generating HDL, the only pathway that eliminates excess cholesterol from nonhepatic cells. ABCA1 mediates apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) binding to the cell surface and the loading of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids onto apoA-I to form pre-βHDL (6–9). Recently, it was reported that the capacity of macrophages to mediate cholesterol efflux to HDL is strongly and inversely associated with both carotid intima-media thickness and the likelihood of angiographic coronary artery disease, independent of HDL cholesterol levels (10). However, despite the physiological importance of this pathway, the mechanism by which ABCA1 mediates cholesterol efflux remains unclear (11).

ABCA1 has two intracellular nucleotide-binding domains (NBD) (Fig. 1), whose amino acid sequences are highly conserved among ABC proteins. Chambenoit et al. reported that substituting the Walker A lysine residue in either NBD with methionine (K939M or K1952M) abolishes the ability of apoA-I to bind to ABCA1-expressing cells and inhibits cholesterol secretion to apoA-I (12). Because these lysine residues are essential for ATPase activity (13) and thus for the transport activity of ABC proteins, it was predicted that ABCA1 induces a local and transient modification in the spatial arrangement of lipid species on the outer membrane leaflet and that this membrane modification generates apoA-I-docking sites on the cell surface (8, 14–16).

Fig. 1.

Secondary structure of ABCA1. The HA tag-insertion sites and Walker A lysine mutations are indicated by open circles and open squares, respectively. The TEV protease recognition sequence was introduced between R1272 and R1273, as indicated by the filled triangle. The two cysteine residues in ECD1 and three cysteine residues in ECD2 involved in S-S bond formation between the ECDs are indicated by filled circles.

ABCA1 has two large extracellular domains (ECD) after transmembrane helix 1 (TM1) and TM7 (Fig. 1). Two intramolecular disulfide bonds are formed between the two ECDs of ABCA1, and these disulfide bonds are necessary for apoA-I binding and HDL formation (17). Several groups have used cross-linking experiments to show that apoA-I directly binds to ABCA1 (6, 8, 18–21). Because a 3-Å cross-linker can cross-link apoA-I with ABCA1 (19) and the K939M mutant cannot bind or be cross-linked to apoA-I (22), it is likely that apoA-I interacts with specific conformations of the ECDs that are linked by the two disulfide bonds and formed in an ATP-dependent manner. However, the importance of a direct apoA-I-ABCA1 interaction in HDL formation is still controversial, and it is unclear what conformation of ABCA1 mediates apoA-I binding and how this specific conformation is formed. In this study, we analyzed ATP binding and hydrolysis for each NBD of ABCA1 and examined the contribution of the NBDs to apoA-I binding and HDL formation. On the basis of these results, we determined that ATP hydrolysis-dependent conformational changes in the ECDs of ABCA1 are associated with apoA-I binding and cholesterol efflux by ABCA1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The mouse anti-ABCA1 monoclonal antibody KM3110 was generated against the 20 C-terminal amino acids of ABCA1 (23). The rat anti-ABCA1 monoclonal antibody KM3073 was generated against ECD1 of ABCA1 (23). An anti-ABCA1 NBD2 rabbit polyclonal antibody was generated against the purified NBD2 of ABCA1 (13). Anti-GFP and anti-HA (F-7) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-Flag rabbit polyclonal antibody was purchased from Sigma. Tobacco etch virus (TEV)-derived ProTEV protease was obtained from Promega. Recombinant apoA-I and Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I were prepared as previously reported (24). The remaining chemicals were purchased from Sigma, Amersham Biosciences, Wako Pure Chemical Industries, and Nacalai Tesque.

Cell culture

HEK293 cells were grown in a humidified incubator (5% CO2) at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Plasmids

The expression vectors for wild-type ABCA1, ABCA1-K939M, ABCA1-K1952M, and ABCA1-K939M,K1952M that were tagged with GFP at the C terminus were generated as previously described (7, 13). The influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope sequence (coding YPYDVPDYA) was introduced between G207 and D208 as previously reported (25). To introduce an HA tag or a Flag tag at several sites, a MulI site (acgcgt) was introduced just after K136, N349, R443, K568, G1421, K1490, D1567, and E1622 of ABCA1-GFP using a QuickChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Oligos containing an HA tag, 5′-cgcgttacccatacgatgttccagattacgcca-3′ and 5′-cgcgtggcgtaatctggaacatcgtatgggtaa-3′, or a Flag tag, 5′-cgcgtgactacaaagacgatgacgacaaga-3′ and 5′-cgcgtcttgtcgtcatcgtctttgtagtca-3′ were introduced into the MulI site. The TEV protease recognition sequence (coding ENLYFQG) was introduced between R1272 and R1273 of ABCA1-GFP by PCR using primers 5′-agacgaaacagggaaaacctgtacttccagggtcgggccttcgg-3′ and 5′-ccgaaggcccgaccctggaagtacaggttttccctgtttcgtct-3′. The mutated DNA was confirmed by sequencing.

Transfection and generation of stable ABCA1 transformants

HEK293 cells were transfected with each expression vector using Lipofectamine and Plus reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To establish stable transformants, the cells were selected with G418, and single colonies were isolated.

Western blotting

Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in lysis buffer A (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 1% Triton X-100) containing the following protease inhibitors: 100 μg/ml (p-amidinophenyl)methanesulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 2 μg/ml aprotinin. The samples were electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, blotted, and probed with the indicated antibodies.

Cellular lipid release assay

Cells were subcultured in poly-L-lysine-coated 24-well plates at a density of 3 × 105 cells in DMEM containing 10% FBS. After 24 h incubation, the cells were washed twice with DMEM, and then incubated in DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and 5 μg/ml recombinant apoA-I. After 24 h incubation, the cholesterol content in the medium was determined using a colorimetric enzyme assay or a fluorescence enzyme assay (26, 27).

Biotinylation of cell surface proteins

Cell monolayers were kept on ice for 10 min. The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS+ (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1 mg/ml CaCl2 and 0.1 mg/ml MgCl26H2O) and incubated with 0.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-biotin solubilized in PBS+ for 30 min on ice in the dark. The cells were washed with TBS (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mg/ml CaCl2 and 0.1 mg/ml MgCl26H2O) to remove unbound sulfo-NHS-biotin and lysed in lysis buffer B (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and 1% sodium deoxycholate) containing protease inhibitors. Immobilized monomeric avidin gel (Pierce) was added to the cell lysates to precipitate the biotinylated proteins, which were electrophoresed on a 7% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and immunodetected.

ApoA-I binding

Cells grown on collagen-coated coverslips were incubated with DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I (5 μg/ml) for 15 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min, and observed with a confocal microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss).

Anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody staining

Cells grown on collagen-coated coverslips were incubated with anti-HA antibody (1 μg/ml) or anti-Flag antibody (1:1000) in DMEM containing 0.02% BSA for 15 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min. After blocking with PBS+ containing 1% BSA, the cells were incubated with an Alexa546-conjugated secondary antibody and observed with a confocal microscope.

Cellular ATP depletion

Cellular ATP was depleted by incubating with 10 mM sodium azide and 10 mM 2-deoxy D-glucose in glucose-free DMEM containing 0.02% BSA for 10 min.

ATP binding

Membrane fractions were prepared from HEK293 cells that stably or transiently expressed ABCA1-GFP. Membranes were incubated on ice with 20 μM [α32P]8N3ATP, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ouabain, 0.1 mM EGTA, and 40 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5) in a total volume of 10 μl for 10 min and then irradiated for 5 min (254 nm, 8.2 mW/cm2) on ice. Unbound ATP was removed by adding 400 μl ice-cold 40 mM Tris-Cl buffer containing 0.1 mM EGTA and 1 mM MgCl2 and then centrifuging (15,000 rpm, 5 min, 2°C) the samples. This washing procedure was repeated. The pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer B (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and 1% sodium deoxycholate), and ABCA1 was immunoprecipitated with KM3110. The samples were electrophoresed on 7% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then analyzed by autoradiography. The same membranes were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

Nucleotide trapping

Membrane fractions were prepared from HEK293 cells that stably or transiently expressed ABCA1-GFP. The membrane fractions were incubated with 5 μM [α32P]8N3ATP or [γ32P]8N3ATP, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ouabain, 0.1 mM EGTA, and 40 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5 in a total volume of 10 μl at 37°C. The specific activity of [γ32P]8N3ATP was 1.6-fold higher than that of [α32P]8N3ATP. The reactions were stopped by adding 400 μl of ice-cold 40 mM Tris-Cl buffer containing 0.1 mM EGTA and 1 mM MgCl2. Supernatants containing unbound ATP were removed from the membrane pellets after centrifugation (15,000 rpm, 5 min, 2°C), and the procedure was repeated. The pellets were resuspended in 8 μl of TE buffer containing 1 mM MgCl2 and irradiated for 5 min (254 nm, 8.2 mW/cm2) on ice. The samples were electrophoresed on 7% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then analyzed by autoradiography. The same membranes were analyzed by Western blotting using the anti-ABCA1 antibody KM3073 or an anti-GFP antibody.

TEV protease digestion

Immunoprecipitated ABCA1 was digested with TEV protease (0.2 units/μl) at 30°C for 30 min according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as the means ± SD. The statistical significance of differences between mean values was analyzed using the nonpaired t-test. Multiple comparisons were performed using Dunnett's test following ANOVA. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

ApoA-I binding to ABCA1 is ATP-dependent

To characterize the interaction between apoA-I and ABCA1-expressing cells, the effects of depleting cellular ATP were examined. When Alexa 546-labeled apoA-I was added to the medium, apoA-I bound to ABCA1-expressing HEK293 cells within 10 min but not to the parental HEK293 cells, as previously reported (24, 28) (Fig. 2A). When the intracellular ATP levels were reduced by incubating the cells with sodium azide and 2-deoxy-D-glucose for 10 min, apoA-I binding was abolished, although ABCA1 expression on the plasma membrane was not affected (Fig. 2B). Incubating the cells in glucose-containing medium for 10 min after ATP depletion restored apoA-I binding to levels comparable to before ATP depletion (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that apoA-I binding is ABCA1- and ATP-dependent. The apoA-I on the cell surface may include both the direct binding to ABCA1 and the secondary association of lipidated apoA-I to the cell surface.

Fig. 2.

Effect of ATP depletion on apoA-I binding. A: HEK or HEK/ABCA1 cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I for 10 min. B: HEK/ABCA1 cells were incubated with (middle panel) or without (upper panel) 10 mM NaN3 and 10 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose in glucose-free DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and 5 μg/ml Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I for 10 min. After ATP depletion, the cells were incubated with DMEM containing glucose, 0.02% BSA, and 5 μg/ml Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I for 10 min (lower panel). Differential interference contrast (DIC) images of cells are shown on the right. Bar, 10 μm.

Two intact NBDs are required for apoA-I binding and cholesterol efflux

The contribution of the two NBDs of ABCA1 to apoA-I binding and cholesterol efflux by ABCA1 was analyzed. Wild-type ABCA1 mediated apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux. However, cholesterol efflux was impaired in cells expressing ABCA1-K939M,K1952M, a mutant in which the Walker A lysines in both NBDs are replaced with methionines, or the single Walker A lysine mutants ABCA1-K939M or ABCA1-K1952M, in which the Walker A lysine in NBD1 or NBD2 is replaced with methionine (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, these mutations did not significantly affect the expression levels (Fig. 3A), and at least a fraction of the mutants were expressed on the plasma membrane (Fig. 3C). ApoA-I binding was also impaired when either Walker A lysine was replaced with methionine (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that the two intact NBDs are required for apoA-I binding and apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux by ABCA1.

Fig. 3.

Effects of Walker A lysine mutations on cholesterol efflux and apoA-I binding. A: Cell lysates (15 μg of protein) were separated by 7% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and ABCA1-GFP was analyzed with an anti-GFP antibody. The amount of vinculin was examined as a loading control. B: Free cholesterol efflux was analyzed. HEK293 cells stably expressing wild-type (wt) ABCA1 or the Walker A lysine mutants ABCA1-K939M, ABCA1-K1952M, or ABCA1-K939M,K1952M were incubated for 24 h in DMEM containing 0.02% BSA with or without 5 μg/ml apoA-I. ApoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux was calculated by subtracting the value obtained in the absence of apoA-I. C: Cells were incubated with DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and 5 μg/ml Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I for 15 min. Bar, 10 μm. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and average values are shown with SD. ***P < 0.001, significantly different from the value for HEK293 cells.

A Walker A lysine mutation abolishes ATP hydrolysis but not ATP binding

It has been reported that the two NBDs in some ABC proteins do not have equivalent roles in the ATP hydrolysis cycle and substrate transport (29–32). To analyze how the two NBDs of ABCA1 interact with ATP and how they are involved in the functions of ABCA1, the effects of Walker A lysine mutations in each NBD on ATP binding were examined (Fig. 4A). Membranes prepared from cells expressing the wild-type or mutant ABCA1 were incubated with 20 μM [α32P]8N3ATP for 10 min on ice and then UV irradiated. Photoaffinity-labeled ABCA1 was immunoprecipitated from wild-type ABCA1-expressing cells but not from the parental HEK293 cells. This labeling was inhibited by 100-fold excess of nonlabeled ATP, indicating that the photoaffinity labeling was specific. A Walker A lysine mutation did not abolish ATP binding to ABCA1, suggesting that the Walker A lysine residues are not essential for ATP binding to ABCA1.

Fig. 4.

Nucleotide binding and occlusion in wild-type and Walker A lysine mutants of ABCA1. A: ATP binding was analyzed by incubating membranes with 20 μM [α32P]8N3ATP for 10 min on ice. ABCA1 was immunoprecipitated after UV irradiation. The amounts of bound nucleotide in mutants were compared with that in wild-type (wt). B: ATP occlusion was analyzed by incubating the membranes with 5 μM [α32P]8N3ATP in the presence or absence of 0.4 mM vanadate (Vi) for 10 min at 37°C. ABCA1 in the membranes was photoaffinity-labeled after removing the unbound ATP. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes, and the amount of bound nucleotides was visualized by autoradiography with a BAS2500 image analyzer (Fujifilm) and compared with wild-type ABCA1 in the absence of vanadate. The amount of ABCA1 was analyzed by immunoblotting the same membrane (IB). C: ATP occlusion was analyzed with 5 μM [α32P]8N3ATP or [γ32P]8N3ATP at 37°C. The average values from three to five experiments are presented with the SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Next, nucleotide binding under ATP-hydrolysis conditions was analyzed. ABCA1 was strongly photoaffinity-labeled as previously reported (7). These results indicate that the nucleotide was occluded in the NBD of ABCA1 at 37°C when membranes expressing wild-type ABCA1 were incubated with 5 μM [α32P]8N3ATP for 10 min at 37°C and then UV irradiated on ice after the free nucleotides were removed (Fig. 4B). The addition of vanadate did not affect the photoaffinity labeling of ABCA1 as previously reported (7). The K939M mutation decreased the photoaffinity labeling by approximately 40%, and vanadate did not affect the labeling. On the other hand, the K1952M mutation drastically decreased the photoaffinity labeling by approximately 95%. Interestingly, the addition of vanadate significantly (1.7-fold) enhanced the photoaffinity labeling of ABCA1-K1952M, suggesting that vanadate stabilizes the nucleotide at NBD1 after ATP hydrolysis. There was no photoaffinity-labeled band with ABCA1-K939M,K1952M.

When [γ32P]8N3ATP was used for the photoaffinity-labeling experiments under ATP-hydrolysis conditions, no photoaffinity-labeled band was observed with the wild-type or any of the ABCA1 mutants (Fig. 4C), although ABCA1 was strongly labeled when [α32P]8N3ATP was used as a control. These results suggest that the occluded nucleotide in the NBD of wild-type ABCA1, ABCA1-K939M, and ABCA1-K1952M is not ATP but ADP, that both NBDs occlude ADP after ATP hydrolysis, and that the features of the two NBDs of ABCA1 are quite different.

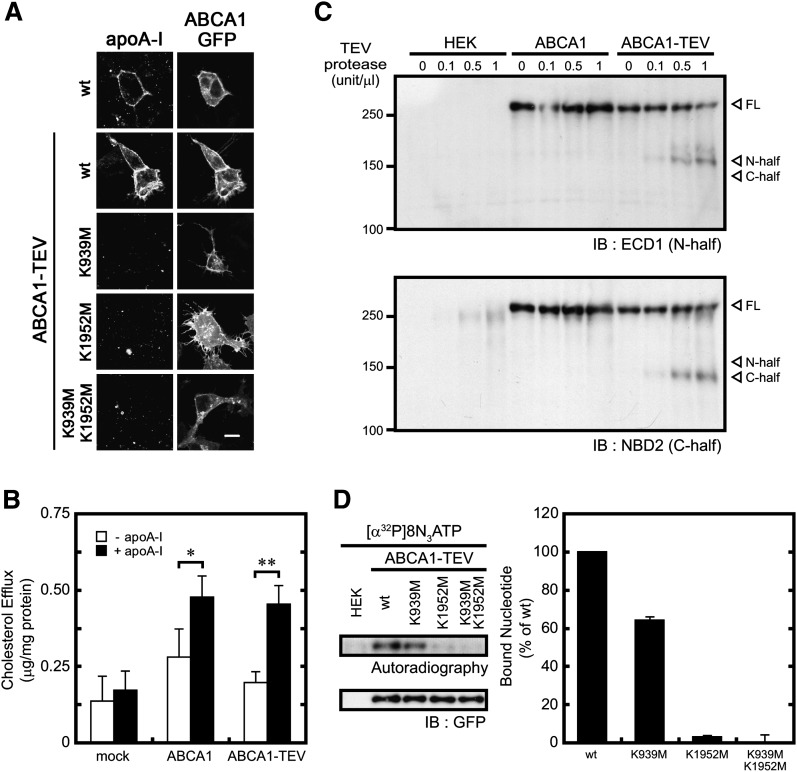

ATP hydrolysis occurs in both NBDs of ABCA1

To analyze the interaction of each NBD with nucleotides in detail, we first performed a limited digestion with trypsin to separate the two NBDs. However, limited trypsin digestion of ABCA1 occurs at two sites: one site is between TM6 and NBD1 (site A), and the other is in the linker region between the two halves of ABCA1 (site B) (13). Thus, it was difficult to quantitatively analyze ATP binding to each NBD. Therefore, we developed a new strategy to separate the two NBDs of ABCA1. First, Edman sequencing showed that the trypsin cleavage site in the linker region (B site) was after R1272 and R1273 (supplementary Fig. I). To cleave ABCA1 specifically at this site, a TEV protease recognition sequence (ENLYFQG; TEV protease cleaves between Q and G) was introduced between R1272 and R1273 (Fig. 1 and supplementary Fig. I). Insertion of the TEV sequence did not affect the cellular localization of ABCA1 or the ability of ABCA1 to bind apoA-I and mediate apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux (Fig. 5A, B). TEV protease-mediated digestion of ABCA1-TEV-GFP yielded a 160 kDa N-terminal fragment and 140 kDa C-terminal fragment (Fig. 5C). ABCA1-GFP, which does not contain an inserted TEV sequence, was not digested by the TEV protease (Fig. 5C), indicating that the digestion by TEV protease is specific and that the two NBDs of ABCA1 can be separated by TEV protease digestion.

Fig. 5.

Effects of inserting the TEV sequence on the function of ABCA1. A: Cells were incubated with DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and 5 μg/ml Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I for 15 min. Bar, 10 μm. B: Cholesterol efflux was analyzed. Cells transiently transfected with ABCA1 were incubated for 24 h in DMEM containing 0.02% BSA with or without 10 μg/ml apoA-I. C: Membranes were incubated with the indicated units of TEV protease for 30 min at 30°C. D: ATP occlusion was analyzed with 5 μM [α32P]8N3ATP in the absence of vanadate at 37°C. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

First, ATP binding to each NBD was analyzed (Fig. 6A). ATP bound equally to both NBDs in ABCA1 as previously reported (32). Walker A lysine mutations in both NBDs did not abolish ATP binding to each NBD. We consistently observed stronger ATP binding to NBD2 in ABCA1-K939M,K1952M-TEV-GFP, although the reason for this higher-affinity interaction is unknown. Next, nucleotide binding to each NBD under ATP-hydrolysis conditions was analyzed. The full-length wild-type and mutant forms of ABCA1 harboring the TEV sequence exhibited a nucleotide occlusion pattern (Fig. 5D) that was similar to that of the TEV-less ABCA1 (Fig. 4B), confirming that insertion of the TEV sequence does not affect the nucleotide-binding properties of ABCA1. When wild-type ABCA1 was incubated with [α32P]8N3ATP and cleaved by the TEV protease after UV irradiation, strong nucleotide occlusion was observed in NBD2 (C-half) and weak occlusion was observed in NBD1 (N-half) (Fig. 6B). However, there was no photoaffinity-labeled band when [γ32P]8N3ATP was used. The K939M mutation reduced the photoaffinity labeling of NBD2 with [α32P]8N3ATP, apparently consistent with the decrease in the photoaffinity labeling of the full-length K939M mutant, although immunoprecipitation and subsequent protease digestion make it difficult to quantitatively compare the mutants (Fig. 6B). Nevertheless, there was no signal for the K939M mutant with [γ32P]8N3ATP. In addition, there were no detectable nucleotide occlusions at either NBD in the K1952M mutant. These results suggest that ATP is hydrolyzed at both NBDs of ABCA1 and that ADP is occluded in both NBDs after ATP hydrolysis. Furthermore, a Walker A lysine mutation has a greater impact on ADP occlusion in NBD2 than in NBD1.

Fig. 6.

Nucleotide binding and occlusion in each NBD of ABCA1. A: Membranes were incubated with 20 μM [α32P]8N3ATP for 10 min on ice and UV irradiated. After immunoprecipitating with KM3110, ABCA1 was treated with or without 0.2 units/μl TEV protease for 30 min at 30°C. B: Membranes were incubated with 5 μM [α32P]8N3ATP or [γ32P]8N3ATP for 10 min at 37°C. After immunoprecipitating with KM3110, ABCA1 was treated with 0.2 units/μl TEV protease for 30 min at 30°C. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and analyzed by autoradiography and immunoblotting (IB). Experiments were performed in duplicate and yielded similar results.

Accessibility of an anti-HA antibody to the HA tag inserted in the ECDs

Because apoA-I binding is ABCA1- and ATP-dependent, we speculated that the apoA-I-binding site(s) are generated in the ECDs of ABCA1 in an ATP-dependent manner (Fig. 2). To determine whether ATP binding and/or hydrolysis causes conformational changes in the ECDs, an HA tag (YPYDVPDYA) was introduced into several sites in the ECDs of ABCA1, and the accessibility of an anti-HA antibody was examined after cellular ATP depletion. First, the hydropathy profile of ABCA1 was analyzed using the Kyte-Doolittle Hydropathy Plot program. Hydrophilic regions that are expected to be located on the surface of ABCA1 were selected for HA tag insertion (supplementary Fig. II). The HA tag was inserted into nine sites within ABCA1-GFP, five in ECD1, and four in ECD2 (Fig. 1). Six HA-insertion mutants (136HA, 207HA, 349HA, 443HA, 1421HA, and 1490HA) were correctly expressed at the plasma membrane and mediated apoA-I binding similar to wild-type ABCA1-GFP (Fig. 7A). However, three HA-insertion mutants (568HA, 1567HA, and 1622HA) only minimally localized to the plasma membrane and did not mediate apoA-I binding, probably due to folding defects.

Fig. 7.

ApoA-I binding and anti-HA antibody staining to ABCA1 with an inserted HA tag. Cells were incubated with DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and 5 μg/ml Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I (A) or 1 μg/ml anti-HA antibody (B) for 15 min. Bar, 10 μm.

To examine the accessibility of the anti-HA antibody, HEK293 cells expressing the HA-insertion mutants were incubated with the anti-HA antibody at 37°C for 15 min in DMEM containing 0.02% BSA. Then cells were fixed and stained with an Alexa 546-conjugated secondary antibody (Fig. 7B). Five HA-insertion mutants (136HA, 207HA, 349HA, 443HA, and 1421HA) on the plasma membrane reacted with the anti-HA antibody. Interestingly, the 1490HA mutant did not react with the antibody, although it was correctly expressed at the plasma membrane and mediated apoA-I binding. It is likely that the epitope (1490) is conformationally inaccessible. Three HA-insertion mutants (568HA, 1567HA, and 1622HA), which only minimally localized to the plasma membrane, were not stained with the anti-HA antibody.

ATP-dependent conformational changes in the ECDs

To analyze ATP-dependent conformational changes in ABCA1, the accessibility of the anti-HA antibody to the HA tag in six mutants was examined after cellular ATP depletion (Fig. 8). The intensity of the HA staining of the 443HA mutant was significantly decreased upon ATP depletion, whereas staining of the other five mutants (136HA, 207HA, 349HA, 1421HA, and 1490HA) was not affected. These results suggest that the accessibility of the anti-HA antibody to the HA tag at 443 is specifically altered by ATP depletion.

Fig. 8.

Effects of ATP depletion on anti-HA antibody accessibility. A: Cells expressing ABCA1 with an HA tag inserted in the ECDs were incubated with or without 10 mM NaN3 and 10 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose in glucose-free DMEM containing 0.02% BSA for 10 min. The cells were then incubated with glucose-free DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and 1 μg/ml anti-HA antibody in the presence or absence of NaN3 and 2-deoxy-D-glucose for 15 min. Bar, 10 μm. B: The intensity of anti-HA staining was calculated and normalized to the intensity of GFP fluorescence using images from 10 cells (136HA, 349HA, 1421HA) or 40 cells (207HA, 443HA) and ImageJ 1.40 software. The relative anti-HA staining was compared in the presence or absence of ATP depletion (upper panel) or between 136HA and 1490HA (lower panel). ***P < 0.001.

To determine the contribution of the two NBDs to the conformational changes in the ECDs, Walker A lysine mutations were introduced into the 443HA mutant, and then the mutants were examined for anti-HA antibody accessibility. Replacing the Walker A lysine residue in either NBD of ABCA1-443HA significantly decreased the intensity of HA staining (Fig. 9C, D) and abolished apoA-I binding (Fig. 10A), whereas cell surface expression or the reactivity with the anti-HA antibody in Western blotting was not affected (Fig. 10C, D). However, the mutation in ABCA1-207HA did not affect HA staining (Fig. 9A, B). When the FLAG tag was inserted into position 443, replacing both Walker A lysine residues, staining with the anti-FLAG antibody also significantly decreased (Fig. 9E, F), suggesting that the decrease in antibody staining did not merely reflect the change in reactivity of the epitope against the antibody. Because the 443HA and 443Flag mutants showed the ATP-dependent apoA-I binding (Fig. 10A) and apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux (Fig. 10B), the insertion of HA or Flag tag into the position 443 did not affect the function of ABCA1. Therefore, the ATP-dependent conformational changes of the 443HA and 443Flag mutants during the function are predicted to be the same as those of the wild-type ABCA1. Together, these results suggest that ATP hydrolysis at both NBDs induces conformational changes in the ECDs that alters antibody accessibility to the region around 443 and that these conformational changes are associated with apoA-I binding.

Fig. 9.

Effects of Walker A lysine mutations on anti-HA and anti-Flag antibody accessibility. Cells expressing ABCA1 with or without an HA tag inserted at position 207 (A) or 443 (C) were incubated with DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and 1 μg/ml anti-HA antibody for 15 min. Bar, 10 μm. B, D: The intensity of anti-HA staining was calculated and normalized to the intensity of GFP fluorescence using images from 40 cells (207HA) or 44 cells (443HA) and ImageJ 1.40 software. The relative anti-HA staining of the Walker A mutants and the wild-type protein was compared. E: Cells expressing ABCA1 with or without a Flag tag inserted at position 443 were incubated with DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and anti-Flag antibody (1:1000) for 15 min. Bar, 10 μm. F: The intensity of anti-Flag staining was calculated and normalized to the intensity of GFP fluorescence using images from 50 cells and ImageJ 1.40 software. ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 10.

Effects of an HA or a Flag tag inserted at position 443 on the function and subcellular localization of ABCA1. A: Cells were incubated with DMEM containing 0.02% BSA and 5 μg/ml Alexa 546-conjugated apoA-I for 15 min. Bar, 10 μm. B: Cholesterol efflux was analyzed. Cells transiently transfected with ABCA1 were incubated for 24 h in DMEM containing 0.02% BSA with or without 10 μg/ml apoA-I. C: Cells were treated with sulfo-NHS-biotin and cell lysates were prepared. Biotinylated surface proteins were precipitated with avidin agarose from 150 μg of cell lysates. The precipitated surface proteins (upper panel) and cell lysates (15 μg; lower panel) were separated and detected with an anti-GFP antibody. Western blots were analyzed using a Fujifilm LAS-3000 imaging system. The amount of cell surface ABCA1 was normalized with total ABCA1. D: Cell lysates were separated and detected with the indicated antibodies. The band intensity of anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody was normalized with that of anti-GFP antibody. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The first step in HDL generation is the binding of apoA-I to the plasma membrane of cells. This step requires ABCA1 that is expressed on the plasma membrane. ABCA1 is induced by the nuclear liver X receptor (LXR) that is activated by oxysterols, which are metabolites of excess cholesterol. Because ABCA1 is a member of the ABC protein family, many of which mediate xenobiotic efflux and lipid transport in an ATP-dependent manner, it has been proposed that membrane phospholipid translocation via ABCA1 generates specific membrane domains that are bound by apoA-I (8, 14–16). In this study, we examined the contribution of the two NBDs to ABCA1 function.

First, the Walker A lysine in each NBD was replaced with methionine. This amino acid substitution in either NBD abolished apoA-I binding and apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux by ABCA1, but it did not affect ATP binding to the NBDs. The amino acid substitution of glutamate in the Walker B motif, which is involved in ATP hydrolysis but not in ATP binding (33), in either NBD abolished apoA-I binding and apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux by ABCA1 (supplementary Fig. III). These results suggest that the two intact NBDs are required for ABCA1 function, that ATP binding to NBDs is not sufficient, and that ATP hydrolysis is required for apoA-I binding and apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux by ABCA1.

To analyze in detail the interaction between each NBD and nucleotides, we identified a trypsin digestion site (R1272 and R1273) in the linker region between the two halves of ABCA1 and inserted a TEV protease recognition sequence that can specifically cleave ABCA1. TEV protease-mediated cleavage of ABCA1 after photoaffinity labeling with [α32P]8N3ATP and [γ32P]8N3ATP, together with the effects of mutations on the photoaffinity labeling of full-length ABCA1, revealed the following characteristics of each NBD of ABCA1: i) ATP binds equally to both NBDs; ii) ATP is hydrolyzed at both NBDs; iii) strong ADP occlusion occurs in NBD2 after hydrolysis, even in the absence of vanadate, a phosphate analog; iv) weak ADP occlusion occurs in NBD1 after hydrolysis in the presence of vanadate; and v) Walker A lysine mutations in either NBD affect ADP occlusion in both NBDs.

The roles of the two NBDs in the ATP hydrolysis cycle have been reported for several ABC proteins. The two NBDs of MDR1 (ABCB1) are virtually equivalent (34), although some nonequivalency has also been reported (35). ATP hydrolysis occurs alternatively (34), and ADP is occluded equally in both NBDs in the presence of vanadate (36). However, in other ABC proteins, the two NBDs are proposed to have nonequivalent roles, one catalytic and the other regulatory. In the case of MRP1 (ABCC1), ATP is hydrolyzed only at NBD2, while NBD1 plays a regulatory role (29). Similar models have been proposed for CFTR (ABCC7) (30), SURs (ABCC8, C9) (31), and ABCA4 (32). MRP1 mainly transports hydrophilic compounds that are conjugated with glutathione (37, 38). SUR1 and CFTR are not active transporters but function as a regulator and a channel (39). In ABCA4, only NBD2 binds and hydrolyzes ATP, whereas NBD1, containing a bound ADP, plays a crucial, noncatalytic role in ABCA4 function (32). Although ABCA4 and ABCA1 have about 40% homology and are predicted to have similar secondary structures, the directions of transport are proposed to be opposite (40). Because the two NBDs of ABCA1 hydrolyze ATP and must be intact for the function of ABCA1, the ATP hydrolysis cycle for ABCA1 may more closely resemble that of MDR1 than that of the other ABC proteins.

Because apoA-I binding is ATP hydrolysis-dependent, we assumed that ATP hydrolysis causes conformational changes in the ECDs to generate apoA-I-binding site(s). To determine whether this is the case, an HA tag was introduced into nine hydrophilic regions in the ECDs, and the accessibility of an anti-HA antibody was examined before and after cellular ATP depletion. We found that HA staining of the 443HA mutant was significantly decreased by ATP depletion, suggesting that the region around 443 moves drastically in an ATP-dependent manner. Replacing the Walker A lysine residue in either NBD of ABCA1-443HA significantly decreased the intensity of HA staining (Fig. 9C, D) and abolished apoA-I binding, whereas the mutation in ABCA1-207HA did not affect HA staining (Fig. 9A, B). When the FLAG tag was inserted into position 443, replacing both Walker A lysine residues, staining with the anti-FLAG antibody also significantly decreased (Fig. 9E, F), suggesting that the decrease in antibody staining did not merely reflect the change in reactivity of the epitope against the antibody. Together, these results suggest that ATP hydrolysis at both NBDs induces conformational changes in the ECD and alters antibody accessibility to the region around 443.

It has been proposed that ATP binding triggers conformational changes in ABC proteins (41). ATP binding alters the conformation from an inward-facing, substrate-binding configuration to an outward-facing, substrate-releasing configuration. ATP hydrolysis is proposed to convert the protein to the basal, inward-facing configuration. Because changes in apoA-I binding and antibody accessibility to 443HA require ATP hydrolysis, it is plausible that the apoA-I-binding site(s) are generated by the buildup of ATP hydrolysis cycles and that they are not due to temporal ATP binding. The extracellular domain of ABCA1 is formed with ECD1 (598 aa) and ECD2 (288 aa) (25), which are connected by two intramolecular disulfide bonds (17). We hypothesize that lipid accumulation within the extracellular domain via ATP hydrolysis-dependent lipid transport causes conformational changes that generate apoA-I-binding site(s) on the surface of the extracellular domain and that apoA-I bound to the site(s) is directly loaded with lipids by ABCA1 (42). Because antibody accessibility was different for only one of six sites in the ECDs, apoA-I may bind to specific regions within the ECDs, although we found no significant effect on apoA-I binding or HA staining when the 443HA mutant was preincubated with the anti-HA antibody or apoA-I (supplementary Fig. IV). These results suggest that the apoA-I binding site is not very close to position 443, although the exposure of position 443 to the surface of the ECD is accompanied by the exposure of the apoA-I binding site. Recently, we reported that lysine residues in the ECDs of ABCA1 contribute to the interaction with apoA-I and that the electrostatic interaction between ABCA1 and apoA-I is predicted to be the first step in HDL formation (21). ATP hydrolysis may cause conformational changes that generate a lysine cluster on the surface of the extracellular domain as apoA-I-binding site(s). This study facilitates our understanding of the mechanism of HDL formation by ABCA1.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ECD

- extracellular domain

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- NBD

- nucleotide-binding domain

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- sulfo-NHS-biotin

- sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimidobiotin

- TEV

- tobacco etch virus

- TM

- transmembrane helix

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (S) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; by the Program for Promotion of Basic and Applied Research for Innovations in Bio-oriented Industry (BRAIN) of Japan; by a grant from the Takeda Scientific Foundation; and by the World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of four figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goldstein J. L., DeBose-Boyd R. A., Brown M. S. 2006. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 124: 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagao K., Tomioka M., Ueda K. 2011. Function and regulation of ABCA1--membrane meso-domain organization and re-organization. FEBS J. 278: 3190–3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodzioch M., Orso E., Klucken J., Langmann T., Bottcher A., Diederich W., Drobnik W., Barlage S., Buchler C., Porsch-Ozcurumez M., et al. 1999. The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease. Nat. Genet. 22: 347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks-Wilson A., Marcil M., Clee S., Zhang L., Roomp K., van Dam M., Yu L., Brewer C., Collins J., Molhuizen H., et al. 1999. Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency. Nat. Genet. 22: 336–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rust S., Rosier M., Funke H., Real J., Amoura Z., Piette J., Deleuze J., Brewer H., Duverger N., Denefle P., et al. 1999. Tangier disease is caused by mutations in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1. Nat. Genet. 22: 352–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oram J. F., Lawn R. M., Garvin M. R., Wade D. P. 2000. ABCA1 is the cAMP-inducible apolipoprotein receptor that mediates cholesterol secretion from macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 34508–34511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka A. R., Abe-Dohmae S., Ohnishi T., Aoki R., Morinaga G., Okuhira K. I., Ikeda Y., Kano F., Matsuo M., Kioka N., et al. 2003. Effects of mutations of ABCA1 in the first extracellular domain on subcellular trafficking and ATP binding/hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 8815–8819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang N., Silver D., Costet P., Tall A. 2000. Specific binding of ApoA-I, enhanced cholesterol efflux, and altered plasma membrane morphology in cells expressing ABC1. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 33053–33058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokoyama S. 2000. Release of cellular cholesterol: molecular mechanism for cholesterol homeostasis in cells and in the body. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1529: 231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khera A. V., Cuchel M., de la Llera-Moya M., Rodrigues A., Burke M. F., Jafri K., French B. C., Phillips J. A., Mucksavage M. L., Wilensky R. L., et al. 2011. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 364: 127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagao K., Kimura Y., Mastuo M., Ueda K. 2010. Lipid outward translocation by ABC proteins. FEBS Lett. 584: 2717–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambenoit O., Hamon Y., Marguet D., Rigneault H., Rosseneu M., Chimini G. 2001. Specific docking of apolipoprotein A-I at the cell surface requires a functional ABCA1 transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 9955–9960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi K., Kimura Y., Kioka N., Matsuo M., Ueda K. 2006. Purification and ATPase activity of human ABCA1. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 10760–10768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamon Y., Broccardo C., Chambenoit O., Luciani M., Toti F., Chaslin S., Freyssinet J., Devaux P., McNeish J., Marguet D., et al. 2000. ABC1 promotes engulfment of apoptotic cells and transbilayer redistribution of phosphatidylserine. Nat. Cell Biol. 2: 399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vedhachalam C., Duong P. T., Nickel M., Nguyen D., Dhanasekaran P., Saito H., Rothblat G. H., Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C. 2007. Mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated cellular lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I and formation of high density lipoprotein particles. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 25123–25130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin G., Oram J. F. 2000. Apolipoprotein binding to protruding membrane domains during removal of excess cellular cholesterol. Atherosclerosis. 149: 359–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hozoji M., Kimura Y., Kioka N., Ueda K. 2009. Formation of two intramolecular disulfide bonds is necessary for ApoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux mediated by ABCA1. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 11293–11300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald M. L., Morris A. L., Chroni A., Mendez A. J., Zannis V. I., Freeman M. W. 2004. ABCA1 and amphipathic apolipoproteins form high-affinity molecular complexes required for cholesterol efflux. J. Lipid Res. 45: 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chroni A., Liu T., Fitzgerald M. L., Freeman M. W., Zannis V. I. 2004. Cross-linking and lipid efflux properties of apoA-I mutants suggest direct association between apoA-I helices and ABCA1. Biochemistry. 43: 2126–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vedhachalam C., Ghering A. B., Davidson W. S., Lund-Katz S., Rothblat G. H., Phillips M. C. 2007. ABCA1-induced cell surface binding sites for ApoA-I. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagao K., Kimura Y., Ueda K. 2011. Lysine residues of ABCA1 are required for the interaction with apoA-I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Epub ahead of print. July 1, 2011; doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang N., Silver D. L., Thiele C., Tall A. R. 2001. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) functions as a cholesterol efflux regulatory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 23742–23747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munehira Y., Ohnishi T., Kawamoto S., Furuya A., Shitara K., Imamura M., Yokota T., Takeda S., Amachi T., Matsuo M., et al. 2004. Alpha1-syntrophin modulates turnover of ABCA1. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 15091–15095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azuma Y., Takada M., Shin H-W., Kioka N., Nakayama K., Ueda K. 2009. Retroendocytosis pathway of ABCA1/apoA-I contributes to HDL formation. Genes Cells. 14: 191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka A. R., Ikeda Y., Abe-Dohmae S., Arakawa R., Sadanami K., Kidera A., Nakagawa S., Nagase T., Aoki R., Kioka N., et al. 2001. Human ABCA1 contains a large amino-terminal extracellular domain homologous to an epitope of Sjogren's Syndrome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 283: 1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abe-Dohmae S., Suzuki S., Wada Y., Aburatani H., Vance D. E., Yokoyama S. 2000. Characterization of apolipoprotein-mediated HDL generation Induced by cAMP in a mouse macrophage cell line. Biochemistry. 39: 11092–11099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amundson D. M., Zhou M. 1999. Fluorometric method for the enzymatic determination of cholesterol. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 38: 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagao K., Zhao Y., Takahashi K., Kimura Y., Ueda K. 2009. Sodium taurocholate-dependent lipid efflux by ABCA1: effects of W590S mutation on lipid translocation and apolipoprotein A-I dissociation. J. Lipid Res. 50: 1165–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao M., Cui H. R., Loe D. W., Grant C. E., Almquist K. C., Cole S. P., Deeley R. G. 2000. Comparison of the functional characteristics of the nucleotide binding domains of multidrug resistance protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 13098–13108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aleksandrov L., Aleksandrov A. A., Chang X. B., Riordan J. R. 2002. The first nucleotide binding domain of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is a site of stable nucleotide interaction, whereas the second is a site of rapid turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 15419–15425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuo M., Tanabe K., Kioka N., Amachi T., Ueda K. 2000. Different binding properties and affinities for ATP and ADP among sulfonylurea receptor subtypes, SUR1, SUR2A, and SUR2B. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 28757–28763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahn J., Beharry S., Molday L. L., Molday R. S. 2003. Functional interaction between the two halves of the photoreceptor-specific ATP binding cassette protein ABCR (ABCA4). Evidence for a non-exchangeable ADP in the first nucleotide binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 39600–39608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tombline G., Bartholomew L. A., Urbatsch I. L., Senior A. E. 2004. Combined mutation of catalytic glutamate residues in the two nucleotide binding domains of P-glycoprotein generates a conformation that binds ATP and ADP tightly. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 31212–31220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senior A. E., al-Shawi M. K., Urbatsch I. L. 1995. The catalytic cycle of P-glycoprotein. FEBS Lett. 377: 285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takada Y., Yamada K., Taguchi Y., Kino K., Matsuo M., Tucker S. J., Komano T., Amachi T., Ueda K. 1998. Non-equivalent cooperation between the two nucleotide-binding folds of P-glycoprotein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1373: 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbatsch I. L., Sankaran B., Bhagat S., Senior A. E. 1995. Both P-glycoprotein nucleotide-binding sites are catalytically active. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 26956–26961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borst P., Evers R., Kool M., Wijnholds J. 2000. A family of drug transporters: the multidrug resistance-associated proteins. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92: 1295–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leslie E. M., Deeley R. G., Cole S. P. 2001. Toxicological relevance of the multidrug resistance protein 1, MRP1 (ABCC1) and related transporters. Toxicology. 167: 3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ueda K., Matsuo M., Tanabe K., Kioka N., Amachi T. 1999. Comparative aspects of the function and mechanism of SUR1 and MDR1 proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1461: 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun H., Molday R., Nathans J. 1999. Retinal stimulates ATP hydrolysis by purified and reconstituted ABCR, the photoreceptor-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter responsible for Stargardt disease. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 8269–8281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgins C. F., Linton K. J. 2004. The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11: 918–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ueda K. 2011. ABC proteins protect the human body and maintain optimal health. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 75: 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.