Background: Nucleolin is an RNA-binding protein that regulates RNA stability.

Results: CDK1 phosphorylates nucleolin at Thr-641/707 to stabilize nucleolin in a heat shock protein 90-dependent manner.

Conclusion: Nucleolin stabilized by Hsp90 contributes to lung tumorigenesis by increasing the level of many tumor-related mRNAs during mitosis.

Significance: Cancer cells exploit the increase in Hsp90 to maintain nucleolin stability and subsequently to increase the nucleus mRNA levels present in the cell nucleus, which might benefit tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Heat Shock Protein, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Mitosis, Phosphorylation, Protein Stability, CDK1, Heat Shock Protein 90, mRNA Stability, Nucleolin

Abstract

Most studies on heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) have focused on the involvement of Hsp90 in the interphase, whereas the role of this protein in the nucleus during mitosis remains largely unclear. In this study, we found that the level of the acetylated form of Hsp90 decreased dramatically during mitosis, which indicates more chaperone activity during mitosis. We thus probed proteins that interacted with Hsp90 by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) and found that nucleolin was one of those interacting proteins during mitosis. The nucleolin level decreased upon geldanamycin treatment, and Hsp90 maintained the cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) activity to phosphorylate nucleolin at Thr-641/707. Mutation of Thr-641/707 resulted in the destabilization of nucleolin in mitosis. We globally screened the level of mitotic mRNAs and found that 229 mRNAs decreased during mitosis in the presence of geldanamycin. Furthermore, a bioinformatics tool and an RNA immunoprecipitation assay found that 16 mRNAs, including cadherin and Bcl-xl, were stabilized through the recruitment of nucleolin to the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of those genes. Overall, strong correlations exist between the up-regulation of Hsp90, nucleolin, and the mRNAs related to tumorigenesis of the lung. Our findings thus indicate that nucleolin stabilized by Hsp90 contributes to the lung tumorigenesis by increasing the level of many tumor-related mRNAs during mitosis.

Introduction

Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90),2 a constituent molecular chaperone, is an abundant protein comprising 2% of the total cellular protein content under non-stress conditions. This protein is essential for many cellular proteins, including transcription factors, protein kinases, and nitric-oxide synthase, that are known to regulate signal transduction. It is also involved in various cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (1–5). Unlike Hsp70, Hsp90 does not typically act for nascent protein folding; instead, it binds to its binding proteins to stabilize protein folding (6, 7). The crystal structure of Hsp90 reveals that the N-terminal domain of Hsp90 binds adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), which is consistent with the observation that ATP hydrolysis is required for conformational changes involved in the refolding of protein substrates or the binding proteins of Hsp90 (8). Geldanamycin (GA), which is a benzoquinone ansamycin, a radicicol, and a macrocyclic anti-fungal antibiotic, competes for the ATP-binding site on Hsp90 to inhibit its activity (9, 10). Hsp90 resides primarily in the cell cytoplasm and forms a major functional component of an important cytoplasmic chaperone complex (11). However, Hsp90 has also been found inside the cell nucleus and outside of cells in stressed, unstressed, and cancer cells (12–15). Most investigations of nuclear Hsp90 focus on how the protein shifts the glucocorticoid receptor into the nucleus and subsequently regulates its nuclear retention (15, 16). One of our previous studies revealed that Hsp90 stabilizes Sp1 through JNK1 phosphorylation during mitosis (17), but the further role of Hsp90 in mitosis remains unclear.

Nucleolin is a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed protein in eukaryotes (18). It is most abundant in the cell nucleus, where it participates in mRNA regulation (19). However, it is also found in the plasma membrane and cytoplasm and is involved in numerous other cellular processes, including cell growth, cytokinesis, neurogenesis, transcription, signal transduction, apoptosis, induction of chromatin condensation, mRNA regulation, and replication (18, 20–24). This diversity in the biological functions of nucleolin apparently results from its complex protein structure. Specifically, nucleolin contains three structure domains: (i) the highly acidic residues and a nuclear localization signal localize in the N terminus; (ii) four ribonucleoprotein RNA binding domains localize in the middle of nucleolin; and (iii) the C-terminal domain, containing arginine-glycine-glycine repeats (RGGs) participates in interactions with ribosomal proteins (22). Although several specific mRNAs, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl, are reported to be protected by nucleolin recruitment (25), more mRNAs affected by the nucleolin need to be further addressed.

Many genes, such as oncogenes, cytokine, and cell cycle genes, are regulated through the post-transcription stage. One of the major mechanisms of regulation is modulation of the mRNA stability (26, 27). Several factors, such as HuR and nucleolin, increase mRNA stability via their recruitment to the 3′-UTR of mRNA (20, 28–30). In addition, numerous microRNAs control the RNA stability by their recruitment to 3′-UTR (31). Most of the 3′-UTRs acquire a poly(A) tail, which plays a critical role in gene expression associated with many processes, including mRNA stability, translocation, and translation (32, 33). A large number of proteins, including heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, nucleolin, and cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF), associate with this machinery to regulate both the efficiency and specificity of mRNA expression, and they modulate its interaction with other nuclear events (20, 34, 35). In this study, we found that Hsp90 could protect nucleolin from degradation and thus facilitates the nucleolin phosphorylation by CDK1. We also identified many mRNAs binding to nucleolin in mitosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Polyclonal antibodies against nucleolin (H-250 and MS-3), and monoclonal antibodies against Hsp90, cyclin B1, glutathione S-transferase (GST), and CDK1 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Monoclonal antibody against GFP was obtained from BD Biosciences PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Polyclonal antibodies, p-NCL(pT641) and p-NCL(pT707), were made by Kelowna International Scientific Inc. (Taipei, Taiwan). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies and cyanine 5-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA). GA, nocodazole, cycloheximide, paraformaldehyde, thymidine, propidium iodide, iodoacetamide, and monoclonal antibody against α-tubulin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. CDK1/CycB kinase and polyclonal antibodies against acetyl-lysine were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). RNase A was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Oligonucleotides were obtained from MD Bio, Inc. (Taipei, Taiwan). Fetal bovine serum was from HyClone Laboratories (Logan, UT). Aceotonitrile and formic acid were purchased from Merck. Trypsin was purchased from Promega BioSciences (San Luis Obispo, CA). TRIzol RNA extraction kit, SuperScriptTMII, Lipofectamine 2000, RNase inhibitor, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), minimum essential medium, and Opti-MEM medium were obtained from Invitrogen. Ammonium bicarbonate was purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker. [γ-32P]ATP (6000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. ATP and alkaline phosphatase were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was purchased from GE Healthcare (Baie d'Urfe, Canada). Glutathione-agarose beads were from Amersham Biosciences. All other chemical reagents used were of the highest purity obtainable.

Cell Culture

Human cervical adenocarcinoma HeLa cells and lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells were grown in 90% DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mm l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 100 units/ml penicillin G sodium at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in an incubator. Human lung embryonic fibroblasts, IMR-90 cell line, were grown in 90% minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mm l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 100 units/ml penicillin G sodium at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in an incubator.

Immunoprecipitation

Cell extracts were prepared, and the protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit. An equal amount of protein was used in each experiment. The supernatants were transferred to new tubes and incubated with anti-Hsp90 antibodies at a dilution of 1:200 at 4 °C for 12 h. The immunoprecipitated pellets were subsequently incubated with protein G-Sepharose, washed three times with lysis buffer, and separated on SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the gels were processed for immunoblotting with anti-nucleolin (1:2000), anti-Hsp90 (1:2000) and anti-CDK1 (1:2000) antibodies.

In-solution Tryptic Digestion of Proteins from Immunoprecipitated Samples

The immunoprecipitated proteins were finally eluted from the beads by heating at 95 °C for 5 min. The eluted proteins were dialyzed for an additional 16 h against a dialysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 100 mm NaCl, and 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT). One milligram of the eluted proteins was reduced with 5 mm dithiothreitol (65 °C, 1 h) and then alkylated with 15 mm iodoacetamide at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. Before tryptic digestion, 100 mm ammonium bicarbonate buffer was added. For in-solution digestion, trypsin was added to the protein mixture at an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:50 (w/w) at 37 °C for 16 h. Buffer A (95% H2O, 4.9% aceotonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) was added to stop the effect of trypsin, and then the peptide mixture was dried with a high speed low temperature centrifuge. The pellet was stored at −20 °C and dissolved with buffer A to analyze by LC/MS/MS.

Nano-LC-MS/MS Analysis

The dried hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography fractions were reconstituted in 10 μl of buffer C (0.2% formic acid in deionized H2O) and analyzed by LTQ Orbitrap XL (San Jose, CA). Reverse phase nano-LC separation was performed on an Agilent 1200 series nanoflow system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). A total of 8 μl of sample from each hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography fraction was loaded onto an Agilent Zorbax XDB C18 precolumn (inner diameter 0.3 × 5 mm, 5 μm), followed by separation using a C18 column (inner diameter 0.075 × 250 mm, 3 μm) from Micro Tech (Fontana). Buffer C was 0.1% folic acid, and buffer solution D was 0.1% folic acid in 98% acetonitrile. A linear gradient from 5 to 35% D over a 170-min period at a flow rate of 300 nl/min was applied. The peptides were analyzed in the positive ion mode by electrospray ionization (spray voltage = 1.8 kV). The mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent mode, in which one full scan was performed with m/z 300–2000 in the Orbitrap (resolution = 60,000 at m/z 400) using a rate of 30 ms/scan. The five most intense peaks for fragmentation with a normalized collision energy value of 35% in the LTQ were selected. A repeat duration of 30 s was applied to exclude the same m/z ions from the reselection for fragmentation. Peptide/protein identification was first performed with the Mascot search engine (available on the Matrix Science Web site).

Immunofluorescence Microscopic Analysis

HeLa cells were seeded onto glass slides overnight and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4 °C for 15 min. The cells were then rinsed with PBS two times and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 7 min. Next, the cells were pretreated with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS at 25 °C for 60 min, incubated with rabbit anti-nucleolin polyclonal antibodies and mouse anti-Hsp90 monoclonal antibody at a dilution of 1:200 for 1 h, and treated with FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) polyclonal antibodies and cyanine 5-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG polyclonal antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) at a dilution of 1:250 for 1 h. Finally, the cells were washed with PBS, mounted in 90% glycerol containing DAPI, and analyzed using an immunofluorescence microscope (Personal DV Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA) with deconvolution function (softWORX).

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA of cells was isolated with a TRIzol RNA extraction kit, and 3 mg of RNA was subjected to RT-PCR with SuperScript III. The primers used to perform PCR for nucleolin were 5′-ATGGTGAAGCTCGCGAAGGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-ATCCTCCTCTTCATCACTGT-3′ (antisense), and primers used to perform PCR for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were 5′-CCATCACCATCTTCCAGGAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTG-3′ (antisense). PCR products were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Transfection

Cells (2.5 × 105) were seeded on a 3.5-cm dish and were then transfected when they reached 40–50% confluence with plasmids by using Lipofectamine 2000 in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions with slight modifications. For use in transfection, 1 mg of GFP, GFP-nucleolin plasmids, or shRNA-Hsp90 was combined with 1 ml of Lipofectamine 2000 in 200 ml of Opti-MEM medium without serum and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were transfected by changing the medium with 2 ml of Opti-MEM medium containing the plasmids and Lipofectamine 2000 and then incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 6 h. After change of Opti-MEM medium to 2 ml of fresh medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, cells were incubated for an additional 18 h.

RNA Interference

RNA interference vectors used in this study were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility in the Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica (Taipei, Taiwan) as follows: pLKO.1-shRNA-Hsp90–2# (target sequence, 5′-CGCATGATCAAGCTAGGTCTA-3′); pLKO.1-shRNA-Hsp90–4# (target sequence, 5′-CCAACTCATGTCCCTCATCAT-3′); pLKO.1-shRNA-Hsp90–5# (target sequence, 5′-GCAGTAAACTAAGGGTGTCAA-3′); pLKO.1-shRNA-nucleolin-1# (target sequence, 5′-GCGATCTATTTCCCTGTACTA-3′); pLKO.1-shRNA-nucleolin-3# (target sequence, 5′-CCTTGGAAATCCGTCTAGTTA-3′).

Cell Synchronization

Mitotic cells were collected by incubating HeLa cells in complete medium with 45 ng/ml nocodazole at 37 °C, and the cells were collected after different time intervals (0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h) and then prepared for immunoblotting. For another kind of cell synchronization, mitotic cells were collected by incubating HeLa cells in complete medium with 45 ng/ml nocodazole at 37 °C for 16 h. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and added with fresh medium. The releasing cells were then collected after different time intervals (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h) and lysed in RIPA buffer as described above. Equal amounts of proteins from these cell extracts were analyzed using immunoblotting.

In Vitro Calf Intestinal Alkaline Phosphatase (CIP) Assay

For in vitro dephosphorylation of nucleolin, the mitotic cell extracts were combined with 10 units of alkaline phosphatase in CIP buffer containing 50 mm Tris, pH 7.9, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm dithiothreitol in CIP buffer, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h.

Expression of Plasmids

pEGFP-nucleolin contained the cDNA of full-length nucleolin transcribed from the cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter. The pGEX6-nucleolin was constructed to express GST-nucleolin in Escherichia coli. Various nucleolin mutants, pEGFP-nucleolin (T641A/T707A) and pEGFP-nucleolin (T641D/T707D), were constructed using a PCR mutagenesis method.

Purification of GST Fusion Proteins

To purify GST-nucleolin, E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells were cultured to mid-log phase in 200 ml of LB medium containing ampicillin (50 mg/ml). Isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was then added to the medium to a final concentration of 1 mm. The cells were harvested 4 h after the treatment, suspended in ice-cold buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mm leupeptin), and homogenized using sonication for 1 min. Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was mixed with 0.2 ml of glutathione-agarose beads. The beads were washed five times with buffer A, and the GST fusion proteins were finally eluted from the beads by adding buffer A containing 20 mm glutathione. The eluted GST fusion proteins were dialyzed for an additional 16 h against a dialysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 100 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT. The dialyzed GST fusion proteins were then stored at −80 °C until use.

In Vitro CDK1 Kinase Assay

For the in vitro phosphorylation analysis, full-length nucleolin protein was prepared from HeLa cells by using immunoprecipitation with anti-nucleolin antibodies, and the different GST-nucleolin fragments and the point mutations of nucleolin were purified from E. coli BL21 (DE3). These different Sp1 proteins and active CDK1 were used to examine nucleolin phosphorylation in vitro. Each reaction (20 ml) contained 1 mg of purified nucleolin, 15 ng of CDK1-cyclin B, 2 μl of [γ-32P]ATP (6000 Ci/mmol), 1 mm ATP, and 3 μl of 5× kinase buffer containing 500 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT. The phosphorylation reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 15 min. After the incubation, one-half of the reaction was added to 10 μl of 2× electrophoresis sampling buffer, which was then heated to 95 °C for 5 min. Proteins in the mixtures were immediately separated using SDS-PAGE, followed by drying and autoradiography.

RNA Immunoprecipitation Assay

HeLa cells were grown to 70% confluence and lysed with lysis buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 40 mm KCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 1 unit/ml RNaseOUT) for 20 min on ice. The cell extract was incubated with nucleolin antibodies (MS-3) and protein G-agarose beads at 4 °C overnight. Immunoprecipitated complexes were washed three times with lysis buffer, and bound RNAs were extracted by TRIzol reagent. The levels of mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR.

Heat Map Plots

Heat maps were drawn using the image function. The color coding is derived using the ranking of the raw data in the distribution of measures for that sample. Shades of blue represent down-regulation, and shades of red represent up-regulation. The intensity of the color was determined by the distance (in S.D. values) from the mean of the trimmed distribution.

Histological Analysis and Immunohistochemistry

K-Ras-derived lung tumor excised from bitransgenic mice or clinical resected specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin for 24 h, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 mm) were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For immunohistochemistry, sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in a graded series of ethanols. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked by 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 30 min. Sections blocked by 3% BSA in PBS were incubated with appropriate diluted primary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. The immunal reactivity was visualized with a Vectastain ABC kit from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA).

RESULTS

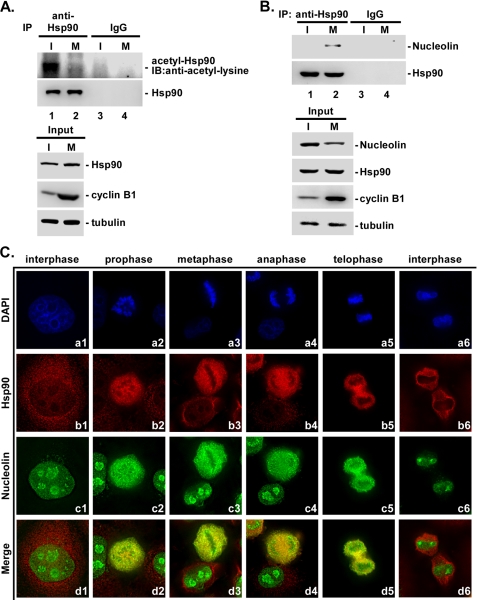

Hsp90 Colocalizes with Nucleolin during Mitosis

Although most previous studies on Hsp90 have focused on its role in interphase (3), our previous studies found that Hsp90 is also important for Sp1 stability during mitosis by affecting the phosphorylation of Sp1 (17). Due to the acetylation, Hsp90 can decrease its chaperone activity (36). In the present study, we first checked the acetylation level of Hsp90 during interphase and mitosis (Fig. 1A). Results revealed that the acetylation of Hsp90 dramatically decreased in mitosis compared with that seen in interphase, which indicated that Hsp90 possessed more chaperone activity in mitosis. To further study the role of Hsp90 in mitosis, we also probed the Hsp90-interacting proteins in interphase and in mitosis with mass spectrometry. Immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments were carried out using anti-Hsp90 antibodies to probe the interacting proteins of the lysates prepared from interphase and mitosis. More than 100 proteins were identified with the LC/MS-ObiTrap mass spectrometry and were then analyzed using Ingenuity to define the functional groupings of those interacting proteins (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, many interacting proteins were related to chaperones, the cytoskeleton, mRNA processing, cell adhesion, methyltransferases, and glutamyltransferases in either interphasic or mitotic cells, but the repertoires were very different. Because different nucleolin isoforms, including cDNA FLJ45706 fis, nucleolin, and putative uncharacterized protein NCL, were probed in mitosis, we decided to focus on nucleolin to study the role of Hsp90 in nucleolin. To confirm the data generated from mass spectrometry, an IP assay was performed to study the interaction between Hsp90 and nucleolin (Fig. 1B). Those results indicated that no interaction signal was found in interphase, but it indeed was present in mitosis. Furthermore, we also employed immunofluorescence to observe the localization of nucleolin and Hsp90 during the cell cycle (Fig. 1C). Data showed that the genome was more relaxed during interphase compared with other stages of the cell cycle and that the nucleolin was prominently localized at the outer layer of nucleoli and was present at a lower concentration throughout the nucleoplasm (Fig. 1C, a1 and c1); however, almost all Hsp90 remained in the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 1C, b1). Therefore, the interaction between nucleolin and Hsp90 was not obvious in the interphase stages (Fig. 1C, d1). When the cell cycle entered the prophase stage, the genome was condensed, the nuclear membrane and nucleoli were disrupted, and the nucleolin began to disperse throughout the cell and ultimately localized at the chromosome periphery (Fig. 1C, a2 and c2). In this stage, both nucleolin and Hsp90 significantly colocalized (Fig. 1C, d2). During metaphase, the chromosomes were packaged more tightly and aligned in the center area of the cell. During this phase, both nucleolin and Hsp90 were significantly colocalized around the tightly packaged chromosomes (Fig. 1C, a3, b3, c3, and d3). Subsequently, the chromosomes began to separate into two parts during anaphase (Fig. 1C, a4), and both nucleolin and Hsp90 remained colocalization (Fig. 1C, b4, c4, and d4). When two daughter cells separated during telophase, nucleolin and Hsp90 were slightly colocalized with each other (Fig. 1C, a5, b5, c5, and d5). Until the interphase stage, when two daughter cells were formed completely, nucleolin colocalized with the genome and remained in the nucleoli; however, Hsp90 was distributed within the cytoplasm (Fig. 1C, a6, b6, c6, and d6). These results indicated that Hsp90 was prominently colocalized with nucleolin during mitosis.

FIGURE 1.

Hsp90 is deacetylated and interacts with nucleolin in the mitotic period. HeLa cells were treated with 45 ng/ml nocodazole, and the samples were subsequently prepared for an immunoprecipitation assay using anti-Hsp90 and anti-IgG antibodies. Immunoprecipitated samples and lysates only were then analyzed using immunoblotting (IB) with antibodies against Hsp90 and acetyl-lysine antibodies (A) or were analyzed using immunoblotting with antibodies against nucleolin, cyclin B1, and tubulin. Tubulin was used as the internal control (B). HeLa cells synchronized at the G1/S phase by treatment with 2 mm thymidine for 12 h were harvested for use in an immunofluorescence assay using DAPI, cyanine 5-anti-mouse antibodies, and FITC-anti-rabbit antibodies to stain chromatin, Hsp90, and nucleolin, respectively. Based on the packaging of chromatin (a1–a6), the localizations of Hsp90 (b1–b6) and nucleolin (c1–c6) and the merged signal of Hsp90 and nucleolin (d1–d6) in various cell cycle stages were determined (C). I, interphase; M, mitosis.

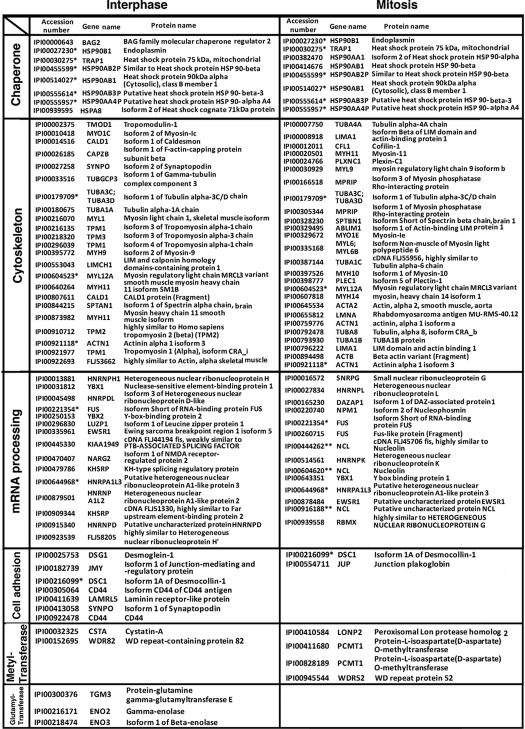

TABLE 1.

Hsp90-interacting proteins in interphasic and mitotic cells

Cellular lysates collected from interphasic or mitotic cells were used in an immunoprecipitation assay with anti-Hsp90 antibodies. The samples were then digested with trypsin and subsequently analyzed using an LC/MS ObiTrap mass spectrometry to identify the interacting proteins. The interacting proteins were then analyzed with Ingenuity to identify their functional groups.

* Protein was interacted with Hsp90 in both interphase and mitosis.

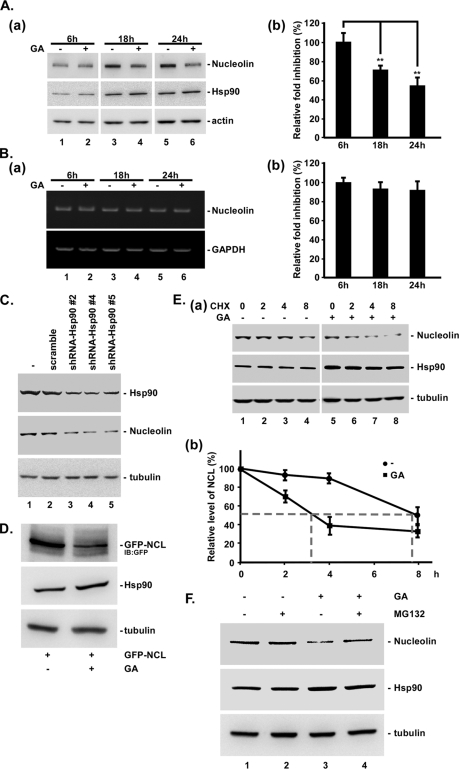

Hsp90 Protects Nucleolin from Degradation

Although it was shown that Hsp90 interacted with nucleolin during mitosis, the significance of this interaction remains unknown. Because Hsp90 is a chaperone, we also studied the protein level of nucleolin in cells with or without GA treatment, an ATPase activity inhibitor of Hsp90 (Fig. 2). These results revealed that the nucleolin level in the GA-treated cells was apparently unchanged within 6 h but declined to 72 and 55% within 18 and 24 h, respectively (Fig. 2A, a and b). However, RT-PCR results indicated no significant difference in the nucleolin mRNA level after GA treatment for 6, 18, and 24 h (Fig. 2B, a and b). Moreover, as Hsp90 was knocked by shRNA, the nucleolin level was obviously decreased (Fig. 2C). These results indicated that the function of Hsp90 in maintaining the nucleolin level was not through affecting its transcriptional activity. In addition, the level of overexpressed nucleolin was also decreased by GA treatment (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, we also examined the role of Hsp90 in nucleolin stability by GA treatment in the presence of cycloheximide (Fig. 2E, a and b). These data indicated that the half-life of nucleolin was ∼7.8 h; however, it was decreased to 3 h upon GA treatment. In addition, GA-induced nucleolin degradation was rescued with MG132 treatment (Fig. 2F). These results indicated that Hsp90 protected nucleolin from degradation, resulting in an increase in nucleolin stability.

FIGURE 2.

Increase in protein stability of nucleolin under GA treatment and Hsp90 knockdown. Cells treated with GA for 6, 18, and 24 h were harvested with 2× sample buffer. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed using immunoblotting with antibodies against nucleolin, Hsp90, and actin (A, a). Quantification was carried out after three independent experiments, and statistical analysis was performed using Student's t tests (**, p < 0.01) (A, b). Cells treated with GA for 6, 18, and 24 h were used to extract the total RNA for RT-PCR (B, a). The mRNA level of nucleolin was quantified after three independent experiments, and the average ± S.D. (error bars) is shown (B, b). Different Hsp90 shRNAs (#2, #4, and #5) and scrambled shRNA were transfected into HeLa cells for 48 h and subsequently harvested with 2× sample buffer. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed using immunoblotting with antibodies against Hsp90, nucleolin, and tubulin. C, GFP-NCL-wt was transfected into HeLa cells for 24 h, and the cells were then treated with GA for 24 h. The samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against GFP, Hsp90, and tubulin, respectively. D, Hsp90 treated with GA was then collected at 0, 2, 4, and 8 h after cycloheximide treatment. Samples were analyzed by using immunoblotting with antibodies against nucleolin and tubulin (E, a). After three independent experiments, the level of nucleolin was quantified (E, b). Cells were treated with 1 μm GA for 24 h and cotreated with 10 μm MG132 for 4 h and then harvested with 2× sample buffer. Samples were analyzed using immunoblotting with anti-nucleolin antibodies (F). Levels of actin, tubulin, and GAPDH mRNA were used as the internal control.

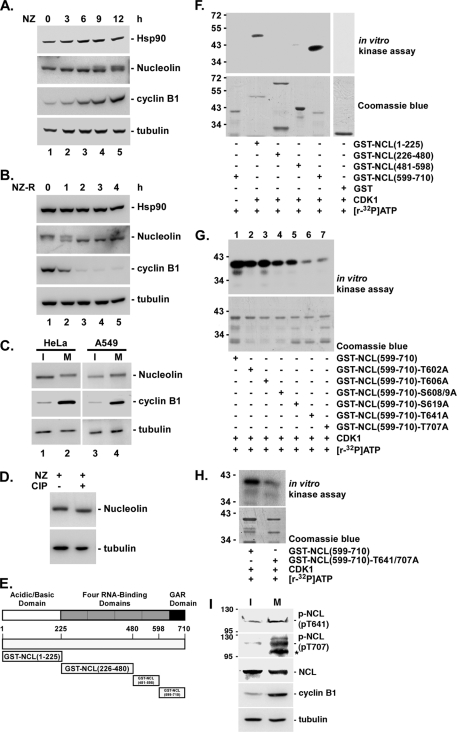

CDK1, the Binding Protein of Hsp90, Phosphorylates Nucleolin to Increase Its Stability during Mitosis

Previous studies have shown that nucleolin is a ubiquitous nucleolar phosphoprotein, and its phosphorylation is highly regulated during cell cycle progression (18). Therefore, we first studied the nucleolin pattern during the cell cycle by immunoblotting, and a band doublet was observed (Fig. 3A). When HeLa cells were synchronized at mitosis by treatment with nocodazole, the upper band was clearly observed in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, as cells from mitosis entered the interphase stage of the next generation, the lower band was clearly observed (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the same results were also found in another cell line, A549 (Fig. 3C). To determine whether this band shift was due to phosphorylation, we performed a CIP assay (Fig. 3D). This result revealed that when the cell lysate from mitotic cells was incubated with alkaline phosphatase at 37 °C, the major signal was the lower band in the gel (Fig. 3D). Previous studies indicated that Hsp90 is required for the activities of many kinases, so the phosphorylation of nucleolin might require Hsp90 involvement. Previous studies have also revealed that CDK1 can phosphorylate nucleolin during mitosis (37, 38). Our present data indicated that Hsp90 interacted with CDK1 during mitosis (supplemental Fig. S1A). Furthermore, the CDK1 level was reduced by GA treatment (supplemental Fig. S1B). These results indicated that there was a strong correlation between the reductions of CDK1 and nucleolin after GA treatment. Based on these findings, Hsp90 might affect CDK1 in order to phosphorylate nucleolin and subsequently stabilize nucleolin. To test this hypothesis, we constructed different truncated and mutated plasmids and expressed them in E. coli, as shown in Fig. 3E. After purification, these isolated proteins were used to perform an in vitro kinase assay with CDK1 (Fig. 3, F and G). First, four truncated fragments, GST-nucleolin(1–225), GST-nucleolin(226–480), GST-nucleolin(481–598), and GST-nucleolin(599–710), were used to perform the CDK1 in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 3, E and F). The results indicated that activated CDK1 phosphorylated two of these truncated proteins, including GST-nucleolin(1–225) and GST-nucleolin(599–710). Although previous studies have shown that Cdc2 kinase phosphorylates threonine in the TPKK motifs, which occur nine times in the N-terminal domain of nucleolin (39), we found that the signal representing phosphorylation on GST-nucleolin(599–710) by CDK1 was more obvious than that representing phosphorylation on GST-nucleolin(1–225). Next, we performed a point mutation within the truncated fragment, GST-nucleolin(599–710), and subsequently used these mutated truncated proteins as the substrates in the CDK1 in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 3G). We found that there was no significant decrease in the phosphorylation level when the GST-nucleolin(599–710) fragment was mutated at residues 602, 606, 608, 609, and 619, but the phosphorylation signal was nearly abolished when either amino acid 641 or 707 was mutated individually (Fig. 3G). Furthermore, to confirm this finding, we also constructed a double mutant within the truncated fragment, GST-nucleolin(599–710) (Fig. 3H). To study the endogenous phosphorylation of nucleolin at Thr-641 and Thr-707, the specific phosphorylation antibodies were used to determine the phosphorylation level of nucleolin in interphase and mitotic cells (Fig. 3I). The results indicated that Thr-641 and Thr-707 of nucleolin could be phosphorylated endogenously, and more phosphorylation signal was found in mitotic cells than in interphase cells (Fig. 3I). These data revealed that the signal was nearly abolished when two phosphorylation residues, Thr-641 and Thr-707, were mutated to alanine. Taken together, these results indicate that CDK1 phosphorylated nucleolin at residues 641 and 707.

FIGURE 3.

CDK1 phosphorylates the Thr-641/707 sites of nucleolin during mitosis. A, HeLa cells were treated with 45 ng/ml nocodazole (NZ) for different time intervals (0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h). The cells were lysed with 2× sample buffer, and then samples were analyzed by using immunoblotting with antibodies against nucleolin. Hsp90 and tubulin were used as internal controls. Cyclin B1 was used as a mitotic marker (A). HeLa cells were synchronized for 16 h with nocodazole. The released cells were collected at different time intervals (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h). These samples were analyzed using immunoblotting with antibodies against nucleolin, Hsp90, cyclin B1, and tubulin (B). Cellular extracts of HeLa and A549 cells in interphase and in mitotic stages cells were harvested with 2× sample buffer and were analyzed using immunoblotting with antibodies against nucleolin, cyclin B1, and tubulin (C). Cells were treated with nocodazole for 16 h, and then harvested to treat with CIP. Samples were then analyzed by using immunoblotting with antibodies against nucleolin and tubulin (D). A schematic diagram and domain organization of GST-nucleolin truncation was constructed and used in this analysis (E). The GST-nucleolin fragments (amino acids 1–225, 226–480, 481–598, or 599–710) were combined with [γ-32P]ATP and activated CDK1 for use in an in vitro kinase assay. The truncated nucleolins were assessed using SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining (F). The GST-nucleolin fragment (amino acids 599–710) and its mutant were used to perform the in vitro kinase assay in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and activated CDK1 (top), and these proteins levels assayed by Coomassie Blue staining were the internal control (bottom) (G). The double-mutated GST-nucleolin protein (T641A/T707A) was also expressed in E. coli, purified, and analyzed with SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining (bottom). The purified proteins were used in an in vitro kinase assay (top) (H). HeLa cells were treated with 45 ng/ml nocodazole. Cell lysates were collected to perform an immunoblot with anti-p-NCL(pT641), anti-p-NCL(pT707), anti-NCL, anti-cyclin B1, and anti-tubulin antibodies (I). Tubulin was the internal control. *, nonspecific band.

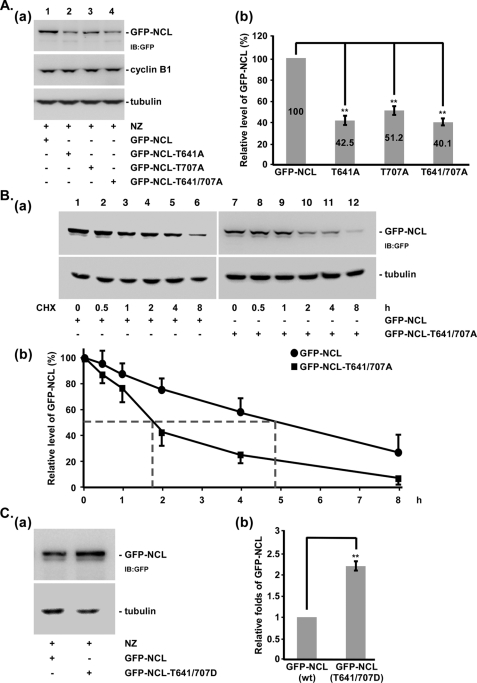

Furthermore, to directly study the relationship between CDK1-induced nucleolin phosphorylation and its stability, we constructed a number of different mutants, including GFP-nucleolin, GFP-nucleolin (T641A), GFP-nucleolin (T707A), and GFP-nucleolin (T641A/T707A), and subsequently transfected each plasmid into HeLa cells to study the protein level in the mitotic cells synchronized by nocodazole treatment (Fig. 4A, a and b). These results indicated that the levels of GFP-nucleolin (T641A), GFP-nucleolin (T707A), and GFP-nucleolin (T641A/T707A) were each reduced to about 50% compared with the level of wild-type GFP-nucleolin. To further strengthen the role of phosphorylation in nucleolin stability, we also transfected GFP-nucleolin or GFP-nucleolin (T641A/T707A) into HeLa cells to determine their protein half-life in the presence of cycloheximide (Fig. 4B, a and b). These data indicated that the half-lives of GFP-nucleolin and GFP-nucleolin (T641A/T707A) were ∼5 and 2 h, respectively. In addition, to directly examine the relationship between nucleolin stability and phosphorylation, we constructed GFP-nucleolin (T641/707D) to mimic the phosphorylation form of nucleolin and transfected it into HeLa cells to study the protein level during mitosis (Fig. 4C). These results showed that the GFP-nucleolin (T641D/T707D) level was increased compared with that of wild-type nucleolin. In addition to CDK1, we also knocked down the other kinases, such as CSNK2A1, PRKACA, and PRKCZ, which have been reported to phosphorylate nucleolin to study the nucleolin stability (21, 40, 41). Data revealed that all of those kinases could not affect nucleolin level (supplemental Fig. S5). These results provide direct evidence to support the idea that nucleolin stability could be maintained by CDK1 via phosphorylation during mitosis in an Hsp90-dependent manner.

FIGURE 4.

The Thr-641/707 sites of nucleolin are involved in its protein stability during mitosis. GFP-NCL, GFP-NCL (T641A), GFP-NCL (T707A), and GFP-NCL (T641A/T707A) were transfected into HeLa cells for 12 h, and the cells were then synchronized at the mitosis stage with nocodazole treatment for 16 h. An equal mitotic cell number was used to determine the NCL level by immunoblotting (IB) with the anti-GFP antibody. Tubulin was used as the internal control. Cyclin B1 was used as an M phase marker (A, a). The levels of GFP-NCL, GFP-NCL (T641A), GFP-NCL (T707A), and GFP-NCL (T641A/T707A) were quantified and normalized with the tubulin level in three independent experiments, and the average ± S.D. (error bars) is shown (A, b). GFP-NCL or GFP-NCL (T641A/T707A) was transfected into HeLa cells for 12 h, and the cells were then synchronized at the mitosis stage by nocodazole treatment for 16 h. Samples were collected at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h after cycloheximide treatment. Samples were analyzed using immunoblotting with anti-GFP and anti-tubulin antibodies (B, a). All experiments in a were performed independently in triplicate and quantified. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t tests (B, b). GFP-NCL or GFP-NCL (T641D/T707D) was transfected into HeLa cells for 12 h, and cells were subsequently synchronized at the mitosis stage by nocodazole treatment for 16 h. An equal mitotic cell number was used to determine the NCL level using an immunoblot with the anti-GFP antibody. Tubulin was used as the internal control (C). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t tests (**, p < 0.01).

Hsp90 Maintains the mRNA Levels during Mitosis through Increasing Nucleolin Stability

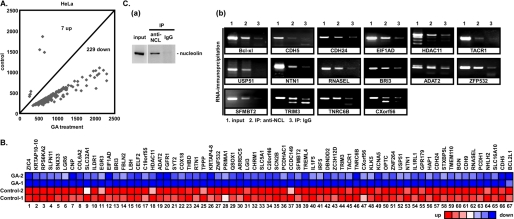

Previous studies have shown that nucleolin can protect mRNAs (18), and herein we found that Hsp90 can stabilize nucleolin. To further elucidate the role of Hsp90 during mitosis, we also studied the mRNA levels in mitotic HeLa cells upon GA treatment. Total RNAs extracted from the mitotic HeLa cells with or without GA treatment were subjected to microarray analysis. Among the 29,187 genes examined, we identified 236 genes that exhibited absolute expression levels of more than 50 in either control or GA-treatment arrays and showed alterations in expression of more than 2-fold between the two genotypes. The genes that exhibited greater than a 2-fold or less than 0.5-fold change after GA treatment compared with the control level are listed in supplemental Table S1 along with additional information concerning each gene. Upon further analyzing these particular genes, we found that most of them were down-regulated after GA treatment compared with the level of the control, whereas seven of them were up-regulated (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, we chose one of the genes, named Bcl-xl, which is reportedly protected by nucleolin, to confirm the array data (supplemental Fig. S3A). The results revealed that GA treatment reduced the level of Bcl-xl mRNA and nucleolin protein during mitosis (supplemental Fig. S3A). In addition, to confirm that there was no cell cycle effect both in the presence and absence of GA treatment, we performed a flow cytometry assay, which indicated that no significant difference occurred in the cell cycle progression in either condition (supplemental Fig. S3B). These results indicate that Hsp90 was able to protect many of the mRNAs during mitosis.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of the novel interacting mRNAs of nucleolin in mitosis. HeLa cells were synchronized into mitosis and were subsequently treated with GA for 4 h or left untreated for comparison. Total RNAs were extracted to perform the cDNA array. The array data were quantified using Microsoft Excel (A). The heat map was generated with GenePattern software, which was also used to compare -fold change patterns of the genes that potentially contained the nucleolin binding sites within the 3′-UTR. In the bottom color spectrum bar, red represents up-regulated genes, whereas blue represents down-regulated genes (B). HeLa cells were treated with nocodazole for 16 h to be synchronized in mitosis and then were subsequently harvested with lysis buffer to perform the immunoprecipitation assay with antibodies against nucleolin and IgG. Samples were analyzed by using immunoblotting with anti-nucleolin antibodies (C, a). The extracted interacting RNAs were used in RT-PCR with various primers from those genes that were decreased after GA treatment and potentially contained the nucleolin binding sites (C, b).

Next, to elucidate how Hsp90 protected these mRNAs during mitosis, we investigated which mRNAs were regulated by nucleolin. We used nucleolin-specific binding motifs, either (U/G/A)CCCG(A/G) or AUUUA (20, 42), the bioinformatics tool, and the mfold Web Server to predict whether nucleolin could bind to the 3′-UTR of these 236 mRNA (supplemental Fig. S2). Of these, it seemed that 67 mRNAs might contain the nucleolin binding motif(s) within their 3′-UTRs (Fig. 5B). To confirm that nucleolin can really bind to the 3′-UTRs of these 67 mRNAs, we also carried out an RNA-IP assay using nucleolin antibody (Fig. 5C). This result revealed that nucleolin was recruited to the 3′-UTRs of 16 mRNAs of the examined mRNAs (Fig. 5C and supplementary Table S2). Taken together, these results indicate that Hsp90 could protect many mRNAs, possibly in part through maintaining nucleolin during mitosis.

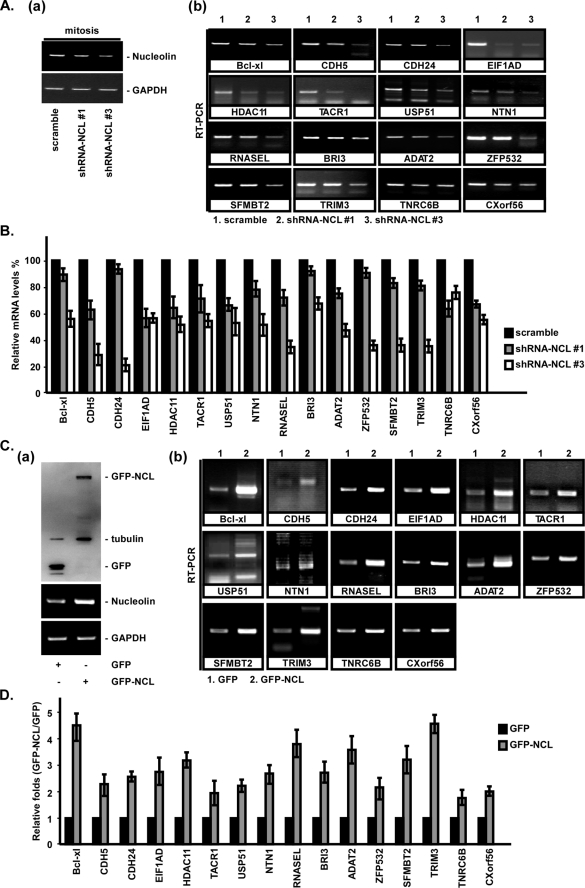

Nucleolin Stabilizes Mitotic mRNA Levels, Which Is Related to Tumorigenesis

Up to this point, we have shown that nucleolin successfully binds to 3′-UTR of many mRNAs in mitosis. To further address the role of nucleolin recruitment to these mRNA 3′-UTRs, we both overexpressed nucleolin and knocked it down by shRNA and subsequently studied the levels of these mRNAs that contained the nucleolin binding motif in their 3′-UTRs (Fig. 6). These results revealed that all of these mRNA levels were decreased after nucleolin was knocked down by shRNA-NCL (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, when nucleolin was overexpressed in cells, all of the mRNA levels were increased dramatically (Fig. 6, C and D). Based on these data, it seems that nucleolin maintained the stability of these mRNAs as the novel binding mRNAs of nucleolin via recruitment to their mRNA 3′-UTRs.

FIGURE 6.

Nucleolin is involved in the mRNA stability in mitosis. Cells were transfected with different nucleolin shRNAs (#1 and #3) and scrambled shRNA for 48 h, and the cells were subsequently synchronized at the mitosis stage by nocodazole treatment for 16 h. Total RNAs were extracted, and the mRNA levels of nucleolin (A, a) and the indicated genes (A, b) were measured using RT-PCR analysis. All experiments were performed independently in triplicate, quantified, and normalized with the level of GAPDH mRNA, and the average ± S.D. (error bars) is shown (B). Plasmids, pGFP and pGFP-NCL, were transfected into HeLa cells for 16 h, and the cells were subsequently lysed with 2× sample buffer. The levels of GFP and GFP-NCL were examined using immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibody, and tubulin was used as an internal control (C, a). RNAs were extracted, and the mRNA expression levels of indicated genes were measured by RT-PCR analysis (C, b). The level of GFP-NCL was quantified by normalizing with that of GFP (D). All experiments were performed independently in triplicate and quantified, and the average ± S.D. is shown.

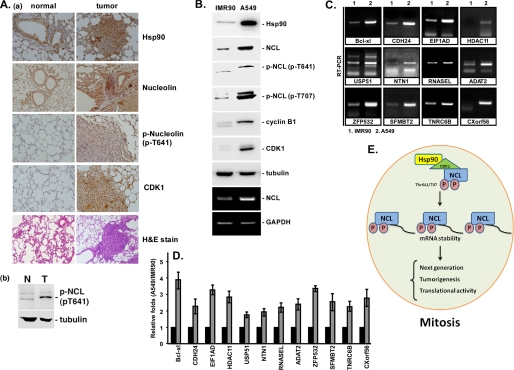

Furthermore, we used the Ingenuity software to group the function of the mRNA products (supplemental Fig. S4), which revealed that most of the proteins were involved in tumorigenesis. Therefore, we also studied the levels of Hsp90, p-NCL(pT641), CDK1, and nucleolin in both lung cancer tissues of bitransgenic mice and a lung cancer cell line, A549 (Fig. 7). These results revealed that both Hsp90, p-NCL(pT641), CDK1, and nucleolin levels were increased in the lung cancer tissue compared with their expression in normal lung tissue (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, these levels, including signal of p-NCL(pT707), were also increased in the lung cancer cell, A549, compared with the corresponding level in the primary lung cell, IMR-90 (Fig. 7B, a). Upon examination of all of the 16 mRNA levels in these two cell types, we found that all of the mRNAs were increased in the lung cancer cells, A549, compared with their expression in IMR-90 (Fig. 7, C and D). Taken together, these data indicate that there was a strong correlation between the increased trend of Hsp90, nucleolin, and the binding mRNAs of nucleolin in lung tumorigenesis (Fig. 7E).

FIGURE 7.

Levels of Hsp90, nucleolin, and interacting mRNAs in lung primary and cancer cells. Hsp90 and nucleolin levels were determined in normal and tumor tissues from bitransgenic mice by using an immunohistochemistry assay with antibodies against Hsp90, nucleolin, p-NCL(pT641), and CDK1. H&E staining was performed to determine the tissue and tumor type (A, a). Samples from normal and K-Ras-induced lung cancer mice were used to study the phosphorylation signal of nucleolin at Thr-641 with an immunoblot assay by using anti-pNCL(pT641) and anti-tubulin antibodies (A, b). The levels of Hsp90 and nucleolin in normal (IMR-90) (N) and tumor (A549) (T) cells were studied by using immunoblotting with antibodies against Hsp90, nucleolin, p-NCL(pT641), p-NCL(pT707), CDK1, and tubulin. Tubulin was used as the internal control (B). The total RNAs from IMR-90 and A549 cells were extracted for RT-PCR to measure the levels of mRNAs of the indicated genes (C). The levels of the indicated mRNAs were quantified and normalized with that of GAPDH. After quantification, the relative -fold change of the mRNAs of the indicated genes from A549 cells were normalized by those from IMR-90 cells. All experiments were performed independently in triplicate and quantified, and average ± S.D. (error bars) is shown (D). The schematic diagram shown here illustrates that Hsp90 is involved in nucleolin stability necessary for maintaining mRNA stability during mitosis (E).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that Hsp90 interacts with nucleolin to stabilize it via phosphorylation by CDK1 in mitosis and also found that numbers of mRNAs related to tumor formation are stabilized by nucleolin.

Chaperone Hsp90 is an important protein that affects the folding of many proteins, including kinases (43). Most of the studies on Hsp90 performed to date have focused on its role in interphase and in the cytoplasm (1). In a previous study, we found that Hsp90 interacts with Sp1 to regulate its transcription activity in its target gene, (12S)-lipoxygenase, through stabilizing the Sp1 level via facilitating the Sp1 phosphorylation by JNK1 (17). We thus decided to address the importance of Hsp90 in mitosis and not only in interphase. Hsp90 has been known to be acetylated by p300 and deacetylated by HDAC6, and it is known that the deacetylated form of Hsp90 has more chaperone activity (36). Therefore, in this study, we studied for the first time the acetylation level of Hsp90 in both interphase and mitosis and found that the acetylation level of Hsp90 was significantly decreased in mitosis compared with the level in interphase (Fig. 1A). This result implies that Hsp90 performs its chaperone activity more during mitosis and thus might have an important role in mitosis. Many proteins may be protected by Hsp90 during mitosis. We used mass spectrometry to globally probe the interacted proteins in interphase and in mitosis. Different interacting proteins were seen between interphase and mitosis (Table 1). Based on these data, we propose that the interacting proteins of Hsp90 are not located in cell cytoplasm and that numerous nuclear proteins might be the interacting proteins of Hsp90. Previous studies have indicated that Hsp90 acts as a chaperone, and it protects many of its interacting proteins by facilitating homeostasis in the cellular environment. According to previous studies as well as our current study (proteins shown in Table 1), both Hsp90 itself and its chaperone components, such as Hsp70, were found in the lysates from both the interphasic and mitotic preparation. These results indicate that, not only in the interphase but also in mitosis, Hsp90 forms a complex to perform its chaperone activity (44). Previous studies have indicated that Hsp90 interacts with the cytoskeleton-related proteins, such as actin or tubulin, to perform its activity (4, 44). In this study, we also found that Hsp90 interacts with many cytoskeleton-related proteins, such as actin, tubulin, and myosin, in interphase and mitosis. In addition, methyltransferases, such as PCMT1 and PCMT2, also interact with Hsp90 in mitosis, indicating that Hsp90 might also be related to the protein methylation during mitosis. Although not all of the interacting proteins of Hsp90 are its clients, the repertoires of the Hsp90-interacting complex are very different in interphase and mitosis, which indicates that the effect of Hsp90 is distinguishable. For example, herein we examined how nucleolin interacted with Hsp90 in mitosis only to address the detailed mechanism and its role in mitosis. However, the roles of other Hsp90-interacting proteins shown in Table 1 remain unclear and thus require further study.

The other novel finding from this study is that Hsp90 affects the nucleolin level by modulating its phosphorylation by CDK1. Previous studies have shown that CDK1 can phosphorylate nucleolin, but it remains unclear which residues are involved in nucleolin phosphorylation, and the resultant effect remains elusive. In this study, we found that CDK1 phosphorylated nucleolin at Thr-641/707 in mitosis and in lung cancer tumorigenesis. Although the major phosphorylation signal by CDK1 was from the C-terminal nucleolin (Thr-641/707), there was still a minor phosphorylation signal at the N terminus. Furthermore, we found that mutating Thr-641/707 to asparagines to mimic phosphorylation could overcome the GA treatment effect in causing the nucleolin degradation. Therefore, nucleolin phosphorylation by CDK1 at the N terminus might relate to other function and thus needs to be studied in the future. In addition, nucleolin is known to have multiple functions, including ribosome biogenesis, chromatin decondensation, histone chaperone activity, nucleogenesis, and cell surface receptor (18, 22, 45–47). Notably, mRNA protection is one of the nucleolin functions (19). Previous studies have pinpointed several mRNAs, including Bcl-2, IL-2, Gadd45, and Bcl-xl, that are protected by nucleolin recruitment to the mRNAs (19, 20, 30, 48). In this study, we used a bioinformatics tool to predict the candidates containing the nucleolin binding motif within their 3′-UTRs; of the 236 genes affected by GA treatment in mitosis, 67 genes were predicted to have a nucleolin binding motif within the 3′-UTR. Finally, we pinpointed 16 mRNAs as the bonding mRNAs of nucleolin by using the RNA-IP assay. The accuracy of the prediction software we used and the RNA-IP resolution might explain why not all 67 mRNAs were defined as the binding mRNAs of nucleolin. Also of note, there are probably many other genes affected by Hsp90 but not through nucleolin protection; it is reasonable to assume this because there are many other proteins that are affected by Hsp90 in mitosis. We uncovered the 16 mRNAs of 236 relevant mRNAs obtained from array that are protected by nucleolin recruiting to their 3′-UTRs in an Hsp90-dependent manner. However, the mechanism of the other mRNAs affected by Hsp90 in mitosis must be clarified in the future.

After Ingenuity analysis, most of the mRNA products are related to tumorigenesis (supplemental Fig. S4). For instance, Bcl-xl is a transmembrane protein present in the mitochondria that is related to the signal transduction pathway of the FAS-L, and is one of several anti-apoptotic factors (49). Furthermore, CDH5 and CDH24, both of which are involved in cell adhesion, are accumulated in several cancer formations (50, 51). The histone deacetylase HDAC11 regulates the expression of IL-10 and has implications in autoimmunity, transplantation, cancer, and other clinical issues (52). Moreover, RNASEL is associated with prostate cancer (53, 54). Tachykinin receptor 1 (TACR1) is highly correlated to the primary pancreatic cancer (55). Netrin 1 (NTN1) and its receptor pathways reportedly play an important role in tumorigenesis (56). In the present study, all of these 16 mRNAs are increased in lung cancer tissues (Fig. 7). Some of these proteins have been previously linked to tumorigenesis, but the roles of others remain unclear in the context of cancer formation and thus require further study. In conclusion, this study suggests that cancer cells exploit the increase in Hsp90 to maintain nucleolin stability and subsequently to increase the nucleus mRNA levels present in the cell nucleus, which might benefit tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the National Cheng-Kung University project of the Program for Promoting Academic Excellence and Developing World Class Research Centers, together with National Science Council, Taiwan, Grants NSC 99-2320-B-006-031-MY3 and NSC 100-2321-B-006-011.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S5.

- Hsp90

- heat shock protein 90

- GA

- geldanamycin

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- CIP

- calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Young J. C., Agashe V. R., Siegers K., Hartl F. U. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 781–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garfinkel M. D., Sollars V. E., Lu X., Ruden D. M. (2004) Methods Mol. Biol. 287, 151–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kimmins S., MacRae T. H. (2000) Cell Stress Chaperones 5, 76–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liang P., MacRae T. H. (1997) J. Cell Sci. 110, 1431–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Citri A., Kochupurakkal B. S., Yarden Y. (2004) Cell Cycle 3, 51–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindquist S., Craig E. A. (1988) Annu. Rev. Genet. 22, 631–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pearl L. H., Prodromou C. (2000) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10, 46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scheibel T., Weikl T., Buchner J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1495–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hubert D. A., Tornero P., Belkhadir Y., Krishna P., Takahashi A., Shirasu K., Dangl J. L. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 5679–5689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jez J. M., Chen J. C., Rastelli G., Stroud R. M., Santi D. V. (2003) Chem. Biol. 10, 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prodromou C., Roe S. M., O'Brien R., Ladbury J. E., Piper P. W., Pearl L. H. (1997) Cell 90, 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gething M. J., Sambrook J. (1992) Nature 355, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gasc J. M., Renoir J. M., Faber L. E., Delahaye F., Baulieu E. E. (1990) Exp. Cell Res. 186, 362–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eustace B. K., Sakurai T., Stewart J. K., Yimlamai D., Unger C., Zehetmeier C., Lain B., Torella C., Henning S. W., Beste G., Scroggins B. T., Neckers L., Ilag L. L., Jay D. G. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanchez E. R., Hirst M., Scherrer L. C., Tang H. Y., Welsh M. J., Harmon J. M., Simons S. S., Jr., Ringold G. M., Pratt W. B. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 20123–20130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kang H. T., Ju J. W., Cho J. W., Hwang E. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51223–51231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang S. A., Chuang J. Y., Yeh S. H., Wang Y. T., Liu Y. W., Chang W. C., Hung J. J. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 387, 1106–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mongelard F., Bouvet P. (2007) Trends Cell Biol. 17, 80–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sengupta T. K., Bandyopadhyay S., Fernandes D. J., Spicer E. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10855–10863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang J., Tsaprailis G., Bowden G. T. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 1046–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Srivastava M., Pollard H. B. (1999) FASEB J. 13, 1911–1922 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ginisty H., Sicard H., Roger B., Bouvet P. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mi Y., Thomas S. D., Xu X., Casson L. K., Miller D. M., Bates P. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8572–8579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Angelov D., Bondarenko V. A., Almagro S., Menoni H., Mongélard F., Hans F., Mietton F., Studitsky V. M., Hamiche A., Dimitrov S., Bouvet P. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 1669–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishimaru D., Zuraw L., Ramalingam S., Sengupta T. K., Bandyopadhyay S., Reuben A., Fernandes D. J., Spicer E. K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27182–27191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khabar K. S. (2010) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 67, 2937–2955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Steinman R. A. (2007) Leukemia 21, 1158–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abdelmohsen K., Lal A., Kim H. H., Gorospe M. (2007) Cell Cycle 6, 1288–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Willimott S., Wagner S. D. (2010) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 1571–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang Y., Bhatia D., Xia H., Castranova V., Shi X., Chen F. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 485–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fabian M. R., Sonenberg N., Filipowicz W. (2010) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 351–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barabino S. M., Keller W. (1999) Cell 99, 9–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Edwalds-Gilbert G., Veraldi K. L., Milcarek C. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 2547–2561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Edmonds M. (2002) Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 71, 285–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ostareck-Lederer A., Ostareck D. H. (2004) Biol. Cell 96, 407–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kovacs J. J., Murphy P. J., Gaillard S., Zhao X., Wu J. T., Nicchitta C. V., Yoshida M., Toft D. O., Pratt W. B., Yao T. P. (2005) Mol. Cell 18, 601–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dranovsky A., Vincent I., Gregori L., Schwarzman A., Colflesh D., Enghild J., Strittmatter W., Davies P., Goldgaber D. (2001) Neurobiol. Aging 22, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tuteja R., Tuteja N. (1998) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33, 407–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kharrat A., Derancourt J., Dorée M., Amalric F., Erard M. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 10329–10336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tuteja N., Huang N. W., Skopac D., Tuteja R., Hrvatic S., Zhang J., Pongor S., Joseph G., Faucher C., Amalric F. (1995) Gene 160, 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhou G., Seibenhener M. L., Wooten M. W. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31130–31137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ghisolfi-Nieto L., Joseph G., Puvion-Dutilleul F., Amalric F., Bouvet P. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 260, 34–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pratt W. B., Toft D. O. (1997) Endocr. Rev. 18, 306–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Terasawa K., Minami M., Minami Y. (2005) J. Biochem. 137, 443–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Erard M., Lakhdar-Ghazal F., Amalric F. (1990) Eur. J. Biochem. 191, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Caizergues-Ferrer M., Mariottini P., Curie C., Lapeyre B., Gas N., Amalric F., Amaldi F. (1989) Genes Dev. 3, 324–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Semenkovich C. F., Ostlund R. E., Jr., Olson M. O., Yang J. W. (1990) Biochemistry 29, 9708–9713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen C. Y., Gherzi R., Andersen J. S., Gaietta G., Jürchott K., Royer H. D., Mann M., Karin M. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1236–1248 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rothstein T. L. (2000) Cell Res. 10, 245–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blancafort P., Magnenat L., Barbas C. F., 3rd (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Katafiasz B. J., Nieman M. T., Wheelock M. J., Johnson K. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27513–27519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Villagra A., Cheng F., Wang H. W., Suarez I., Glozak M., Maurin M., Nguyen D., Wright K. L., Atadja P. W., Bhalla K., Pinilla-Ibarz J., Seto E., Sotomayor E. M. (2009) Nat. Immunol. 10, 92–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mazzucchelli R., Barbisan F., Tarquini L. M., Galosi A. B., Stramazzotti D. (2004) Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 26, 127–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cansino Alcaide J. R., Martínez-Piñeiro L. (2006) Clin. Transl. Oncol. 8, 148–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schulz S., Stumm R., Röcken C., Mawrin C., Schulz S. (2006) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 54, 1015–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Latil A., Chêne L., Cochant-Priollet B., Mangin P., Fournier G., Berthon P., Cussenot O. (2003) Int. J. Cancer 103, 306–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.