Background: NH125 inhibits cancer cell growth through inhibition of eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase (eEF2K).

Results: NH125 induces eEF2 phosphorylation (peEF2) through multiple pathways in cancer cells.

Conclusion: NH125 is not an eEF2K inhibitor in cancer cells. Inhibition of cell growth correlates with induction of peEF2.

Significance: NH125-induced peEF2 corrects a misconception and provides an opportunity for a new multipathway approach to anticancer therapies.

Keywords: AMP Kinase, Drug Discovery, Metabolism, mTOR, Signal Transduction, A-484954, A-769662, NH125, eEF2, eEF2K

Abstract

Eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase (eEF2K) relays growth and stress signals to protein synthesis through phosphorylation and inactivation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2). 1-Benzyl-3-cetyl-2-methylimidazolium iodide (NH125) is a widely accepted inhibitor of mammalian eEF2K and an efficacious anti-proliferation agent against different cancer cells. It implied that eEF2K could be an efficacious anticancer target. However, eEF2K siRNA was ineffective against cancer cells including those sensitive to NH125. To test if pharmacological intervention differs from siRNA interference, we identified a highly selective small molecule eEF2K inhibitor A-484954. Like siRNA, A-484954 had little effect on cancer cell growth. We carefully examined the effect of NH125 and A-484954 on phosphorylation of eEF2, the known cellular substrate of eEF2K. Surprisingly, NH125 increased eEF2 phosphorylation, whereas A-484954 inhibited the phosphorylation as expected for an eEF2K inhibitor. Both A-484954 and eEF2K siRNA inhibited eEF2K and reduced eEF2 phosphorylation with little effect on cancer cell growth. These data demonstrated clearly that the anticancer activity of NH125 was more correlated with induction of eEF2 phosphorylation than inhibition of eEF2K. Actually, induction of eEF2 phosphorylation was reported to correlate with inhibition of cancer cell growth. We compared several known inducers of eEF2 phosphorylation including AMPK activators and an mTOR inhibitor. Interestingly, stronger induction of eEF2 phosphorylation correlated with more effective growth inhibition. We also explored signal transduction pathways leading to NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation. Preliminary data suggested that NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation was likely mediated through multiple pathways. These observations identified an opportunity for a new multipathway approach to anticancer therapies.

Introduction

During the elongation cycle of protein synthesis, phosphorylation of eEF2 inhibits translocation of aminoacyl-tRNA from the A site to the P site of the ribosome and results in inhibition of protein synthesis (1, 2). As one of the most prominently phosphorylated proteins, eEF2 phosphorylation is actually a sensitive indicator of signal transduction in response to various growth and stress stimuli. The best characterized kinase upstream of eEF22 is a highly selective α-kinase eEF2K, also known as Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III (3, 4). It was found that activation of cAMP/PKA, Ca2+/calmodulin, and AMPK pathways could lead to activation of eEF2K and increase of eEF2 phosphorylation (5–7). Other pathways including SAPK/p38, MEK/p90RSK1, and mTOR/S6K1 mediate phosphorylation of eEF2K at sites that inactivate eEF2K activity (5, 8). Inactivation of these pathways can lead to activation of eEF2K and increase of eEF2 phosphorylation. For example, serum deprivation suppresses mTOR/S6K1 activity, which leads to activation of eEF2K and increase of eEF2 phosphorylation (8, 9). Additionally, decrease of pH, such as under hypoxic or ischemic conditions, also increases eEF2 phosphorylation (10). Although eEF2K is the best established upstream kinase for eEF2, recent data suggest that other kinases can also phosphorylate eEF2 directly. In skeletal myocytes, AMPK was implicated in direct phosphorylation of eEF2 independent of eEF2K (11, 12).

NH125 was first reported as a potent agent against drug-resistant bacteria through inhibition of histidine protein kinase (13, 14). Sequence alignment and analysis found that the secondary structure of the catalytic domains between α-kinases and histidine protein kinase bore some resemblance (15). This observation led to the speculation that some histidine kinase inhibitors might also inhibit eEF2K. It was found later that NH125 was indeed a potent and selective inhibitor of mammalian eEF2K in vitro (16). Additional experiments demonstrated that NH125 was efficacious against a broad spectrum of human cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo (16, 17). Recently down-regulation of eEF2K was associated with inhibition of autophagy and enhancement of cytotoxic effects in combination treatments using eEF2K siRNA and other cytotoxic agents (9, 18, 19). These findings suggested that NH125-mediated anticancer activity was due to inhibition of eEF2K.

This study explored the cellular mechanism of NH125 under the assumption that NH125 inhibited cancer cell growth through inhibition of eEF2K. We treated cells with NH125 and measured the phosphorylation status of eEF2. We also suppressed eEF2K expression using eEF2K siRNA. In addition, a highly selective small molecule eEF2K inhibitor A-484954 was used to address potential differences between small molecule inhibition and siRNA interference. The results show that NH125-mediated inhibition of cancer cell growth is not due to inhibition of eEF2K. In fact, NH125 adopts a unique mechanism to induce eEF2 phosphorylation. Pharmacological induction of eEF2 phosphorylation by NH125 is shared by some other reagents. Rapamycin, an mTOR pathway inhibitor (20), and oligomycin, a known activator of the AMPK pathway (21), also induce eEF2 phosphorylation. Among these agents, the potency to induce eEF2 phosphorylation agrees well with their potencies to inhibit cancer cell growth. NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation is unaffected by either eEF2K or the AMPK pathway inhibitor alone. A combination of the inhibitors only achieved partial inhibition. These findings suggest that NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation is mediated through multiple pathways. The implications of these findings are discussed in this report.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Treatments

Cancer cell lines used in this study were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cell culture media were from Invitrogen. Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS or in DMEM supplemented with 1 mm sodium pyruvate and 10% FBS. H1299 was grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 0.45% glucose. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Under serum-free conditions, the cells were incubated with or without compounds in the corresponding media without serum for the indicated time. For nutrient deprivation, cells were incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) for the indicated time.

Enzymatic Assays for eEF2K

GST-tagged eEF2K, myelin basic protein, and calmodulin were purchased from Millipore. Biotinylation of myelin basic protein was done using EZ-LINK® NHS-biotin reagents from Pierce. All the other reagents were purchased from Sigma.

eEF2K activity was measured by the incorporation of radiolabeled phosphate from [γ-33P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) into myelin basic protein. The reactions were carried out in a total volume of 30 μl containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 100 μm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm DTT, 0.0075% Triton X-100, 10 nm calmodulin, 1 μm biotinylated myelin basic protein, 2 nm GST-eEF2K, and an ATP mixture (5 μm ATP with 10 μCi/ml of [γ-33P]ATP). The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 45 min and terminated by adding 40 μl of quench buffer containing 0.04 m EDTA and 1.5 m sodium chloride. At the end, 60 μl of the mixture was transferred to a streptavidin flash plate (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and incubated for 30 min. The plates were washed three times with PBS, and the radioactivity was counted in a scintillation counter.

HTS for eEF2K Inhibitors

The Abbott compound library was screened using mARC format as described previously (22). The deconvoluted hits were confirmed and IC50 values were determined in a 384-well eEF2K enzymatic assay from powder stocks. IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis from 6-point dose-response curves. Structure and purity of the inhibitors including A-484954 and NH125 (Sigma) were determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis. Inhibitor activity was confirmed in the eEF2K enzyme assay.

Proliferation Assays

MTS assay was performed essentially as described previously (23). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with NH125 for 48 h. Viable cells were measured using MTS reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega).

In a CyQuant NF assay, cells were seeded at 2000 cells/well in 96-well plates and treated with compounds for 3 days. Cell proliferation assay was performed using CyQuant NF according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Measurement of fluorescence was taken on a SpectraMAX M5e from Molecular Device (Sunnyvale, CA). Data were analyzed by nonlinear regression using Prism from GraphPad Software, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Mean ± S.E. was used for error bars.

Transfection of siRNA

Human eEF2K siRNA (Dharmacon Inc., Lafayette, CO) at 20 nm was transfected into H460 and H1299 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (LF2000) according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Invitrogen). Transfected cells were incubated in complete or serum-free media for 24 h before being processed for Western blot analysis or for 4 days for CyQuant NF assay.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells at 100,000 cells/well were seeded in 24-well plates. The next day, cells were treated under defined conditions for 6 h, rinsed once in PBS, and harvested in 1× Criterion XT sample buffer containing XT reducing agent (Bio-Rad), protease inhibitor mixtures (Sigma), and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Cell lysates were resolved in Criterion XT 4–12% gels (Bio-Rad) for 50 min. Proteins were transferred to an Immobilon FL PVDF membrane (Millipore) in an iBlot transfer unit (Invitrogen) for 7 min. The membranes were rocked gently in blocking buffer (Li-Cor Bioscience, Lincoln, NE) and probed with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight to eEF2K, phospho-eEF2 at Thr56, eEF2 and phospho-acetyl-CoA carboxylase (pACC) at Ser79 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The antibody against β-actin was from Sigma. Detection of primary antibodies was performed using Alexa Fluor 680 against rabbit and Alexa Fluor 750 against mouse secondary antibodies from Invitrogen. Image acquisition and analysis was performed using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging system (Li-Cor Bioscience).

Immunofluorescent Staining and High Content Imaging Analysis

PC3 cells were plated overnight in 96-well collagen-coated plates at 7500 cells/well under serum conditions. Then cells were treated with compounds and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked in 3% BSA in PBS followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with primary rabbit anti-phospho-eEF2 antibody in 0.3% BSA (1:1000). After washing, the cells were incubated with secondary Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:200) and Hoechst 33342 for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were imaged and analyzed using Cell Health Profiling BioApplication on the ArrayScan® VTI HCS Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific-Cellomics, Pittsburgh, PA) using the ×10 objective.

RESULTS

NH125 Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth

To evaluate the anticancer activity of NH125, we treated an extended panel of cancer cell lines with up to 10 μm NH125 for 48 h followed by measurement of cell viability in MTS assays (Table 1). PC3, A375, HeLa, MG63, LoVo, MiaPaCa, SW620, H1299, and H460 were sensitive to NH125 treatment. Cell lines like H526 and U138 were moderately sensitive to NH125. Some cancer cells including B16F10, HCT15, MCF7, SE, and U87MG were resistant with less than 50% inhibition at 10 μm NH125. Kasumi-1 was the most resistant line with no inhibition at all at 10 μm NH125. Because Kasumi-1 has a doubling time around 36 h, the lack of efficacy indicates that NH125 may spare slow growing cells. Consistent with previous findings, NH125 inhibited the growth of many types of cancer cells (16, 17).

TABLE 1.

Effect of NH125 on cancer cell growth

| Cell lines | Cancer type | IC50 |

|---|---|---|

| μm | ||

| PC3 | Prostate cancer | 1.29 |

| A-375 | Melanoma | 2.30 |

| HeLa | Cervical cancer | 2.47 |

| MG63 | Osterosarcoma | 2.89 |

| LoVo | Colon cancer | 3.50 |

| MiaPaCa | Pancreatic cancer | 3.65 |

| SW620 | Colon cancer | 6.96 |

| H1299 | NSCLC | 7.30 |

| H460 | NSCLC | 7.34 |

| H526 | SCLC | 9.22 |

| U138 | Glioblastoma | 9.66 |

| B16F10 | Mouse melanoma | >10.00 |

| HCT15 | Colon cancer | >10.00 |

| MCF-7 | Breast cancer | >10.00 |

| S.E. | Lymphoid leukemia | >10.00 |

| U87MG | Glioblastoma | >10.00 |

| Kasumi-1 | AML | NDa |

a ND, no detected inhibition at 10 μm NH125.

NH125 Inhibits eEF2K in Vitro but Induces Cellular eEF2 Phosphorylation

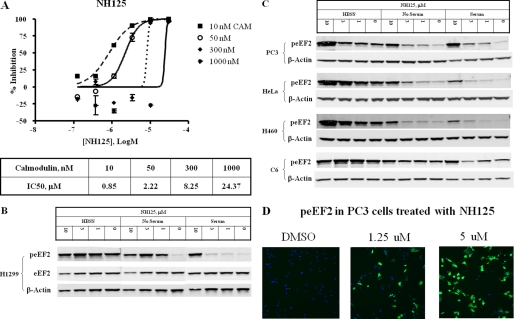

Enzymatic assays in vitro confirmed that NH125 inhibited eEF2K activity (Fig. 1A). Because eEF2K is a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzyme, we tested the effect of calmodulin on NH125. As shown in the figure, IC50 values of NH125 increased as calmodulin concentrations increased, suggesting that NH125 may compete with calmodulin binding to eEF2K. Consistent with the notion that NH125 was not a competitive inhibitor to ATP, changes of ATP concentration did not affect the IC50 values of NH125 (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

NH125 inhibits eEF2K in vitro and induces cellular eEF2 phosphorylation. A, NH125 inhibits eEF2K in enzymatic assays in the presence of various calmodulin concentrations. B, H1299 cells were treated with NH125 under serum, serum-free, and HBSS conditions for 6 h and processed for Western blot analysis. Phospho-eEF2 (peEF2) antibody was used to measure the phosphorylation level of eEF2. Total eEF2 and β-actin antibodies were used to detect protein levels and served as loading controls. C, additional cell lines including PC3, HeLa, H460, and C6 were treated and processed the same way as in A. Only β-actin was used as loading control because the total eEF2 level tracked well with β-actin under NH125 conditions. D, typical high content analysis images showed PC3 cells treated with NH125 at the indicated concentrations and processed for immunofluorescence staining. Cell nuclei were stained blue. peEF2 was stained green.

To test if inhibition of cancer cell growth by NH125 was mediated through eEF2K, we treated cancer cell lines with NH125 and determined the phosphorylation status of eEF2. Results clearly showed that NH125 induced strong eEF2 phosphorylation. Fig. 1B showed Western blot data from H1299 cells. Cells were treated with NH125 for 6 h in complete serum medium, serum-free medium, and nutrient deprivation conditions in HBSS. In complete medium, the basal level of phospho-eEF2 (peEF2) was low. As the concentration of NH125 increased, the peEF2 level also increased and reached a very high level at 10 μm. The total eEF2 level tracked well with the level of β-actin in NH125-treated samples. Serum withdrawal increased the basal level of peEF2. Nevertheless, treatment of NH125 further enhanced eEF2 phosphorylation to the level comparable with total nutrient deprivation under HBSS conditions. Under HBSS conditions, eEF2 phosphorylation reached a very high level. Increases of NH125 resulted in further increases of peEF2. The same results for an expanded panel of cell lines including PC3, HeLa, H460, and a rat glioma cell line C6 are shown in Fig. 1C. NH125 increased peEF2 among all of the cell lines under the experimental conditions. The drop of peEF2 signal in C6 cells at 3 μm NH125 in serum medium was due to the low total protein loading as evidenced by low level of β-actin. Repeated experiments showed that NH125 induced a concentration-dependent increase of peEF2 in C6 cells (data not shown).

Consistent with Western blot data, high content analysis images also displayed an increase of the peEF2 stain (green) at increasing concentrations of NH125 (Fig. 1D). Nuclear stain of PC3 cells is shown in blue. These results clearly demonstrated that NH125 inhibited eEF2K in vitro, but induced eEF2 phosphorylation in cancer cells.

eEF2K siRNA Inhibits eEF2 Phosphorylation but Not Cancer Cell Growth

It is well established that serum deprivation activates eEF2K and increases eEF2 phosphorylation. Inhibition of eEF2K is expected to reduce peEF2 in the absence of serum. To test the role of eEF2K in human cancer cell growth, we transfected eEF2K siRNA into H460 and H1299 cells and observed the effects. eEF2K siRNA effectively reduced the protein level of eEF2K (Fig. 2A). However, residual eEF2K in eEF2K siRNA-treated samples was able to stimulate peEF2 under 24-h serum-free conditions. Nevertheless, the results showed that reduction of the eEF2K protein level reduced serum withdrawal-induced eEF2 phosphorylation. Another set of the same siRNA-transfected cells was allowed to grow for 4 days before proliferation analysis using CyQuant NF. Fig. 2B showed that reduction of the eEF2K protein had little effect on cancer cell growth under either serum or serum-free conditions. These data are consistent with the fact that reduction of cellular eEF2K activity results in reduction of eEF2 phosphorylation. Apparently, NH125 does the opposite of what is expected for an eEF2K inhibitor in the cancer cells.

FIGURE 2.

Treatment of H460 and H1299 cells with eEF2K siRNA. Cells were transfected with eEF2K siRNA or mock and grown in serum or serum-free conditions for 24 h. Samples were processed for Western blot analysis. Membranes were probed with anti-eEF2K, peEF2, and β-actin antibodies (A). A parallel set of cells transfected with eEF2K siRNA was allowed to grow for 4 days before CyQuant NF analysis for cell proliferation (B). Percent cell proliferation of siRNA-transfected cells over mock transfected control cells was calculated to measure the effect of eEF2K siRNA under either serum or serum-free conditions. Error bars indicate S.E.

Novel eEF2K Inhibitor A-484954 on eEF2 Phosphorylation and Cancer Cell Growth

Could different responses of eEF2 phosphorylation to NH125 and eEF2K siRNA be due to the differences between small molecule and siRNA? To answer this question, we used A-484954, a novel small molecule eEF2K inhibitor identified from a chemical library using HTS (Fig. 3A). A-484954 is a highly selective eEF2K inhibitor with an IC50 value of 0.28 μm against eEF2K in the enzymatic assay and little activity against a wide panel of serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases. In enzymatic assay, the IC50 value of A-484954 was increased as the concentration of ATP increased but unaffected by increasing concentrations of calmodulin (data not shown). Unlike NH125, A-484954 inhibited eEF2 phosphorylation in H1299 cells under both serum-free and HBSS conditions (Fig. 3B). The total protein level of eEF2 was not affected by A-484954 treatments. Inhibition of peEF2 was also clear in PC3, HeLa, H460, and C6 cell lines under serum withdrawal and HBSS conditions (Fig. 3C). These data confirm that cellular inhibition of eEF2K should result in reduction of peEF2. Like eEF2K siRNA, data from the small molecule eEF2K inhibitor A-484954 again points out that induction of eEF2 phosphorylation by NH125 is not due to inhibition of eEF2K.

FIGURE 3.

Highly selective eEF2K inhibitor A-484954 inhibits eEF2 phosphorylation but has no inhibitory effect on growth. Chemical structure of A-484954 and selective kinase profiles are shown in A. H1299 cells were treated with A-484954 under serum, serum-free, and HBSS conditions at the indicated concentrations for 6 h and processed for Western blot analysis (B). Phospho-eEF2 (peEF2) antibody was used to measure the phosphorylation level of eEF2. Total eEF2 and β-actin antibodies were used to detect protein levels and served as loading controls. Additional cell lines including PC3, HeLa, H460, and C6 cells were treated and processed the same way (C). Only β-actin was used as loading control because the total eEF2 level tracked well with β-actin under A-484954-treated conditions. D, PC3 cells were treated with NH125 or A-484954 under either serum (+Serum) or serum-free (−Serum) conditions and assayed for proliferation using CyQuant NF reagents.

To determine the effect on proliferation, we treated PC3 cells with A-484954 side by side with NH125 (Fig. 3D). A-484954 had little inhibitory effect in the presence of serum and only about 40% inhibition at 100 μm under serum-free conditions. Selection of the concentration range was based on the effective concentrations to change cellular eEF2 phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 3C, A-484954 reduced peEF2 by half at 10 μm and reached the maximum level at 100 μm under serum-free and HBSS conditions. A-484954 concentrations that effectively inhibited eEF2 phosphorylation did not result in a significant inhibition of cell proliferation. NH125, however, induced eEF2 phosphorylation at about 1 μm in PC3 cells (Fig. 1B) and showed strong growth inhibition with IC50 values of 0.97 and 1.73 μm under serum and serum-free conditions, respectively (Fig. 3D). These data show that inhibition of eEF2K by A-484954 reduces eEF2 phosphorylation but has little effect on proliferation in the cancer cells.

Induction of eEF2 Phosphorylation Correlates with Growth Inhibition for Multiple Compounds

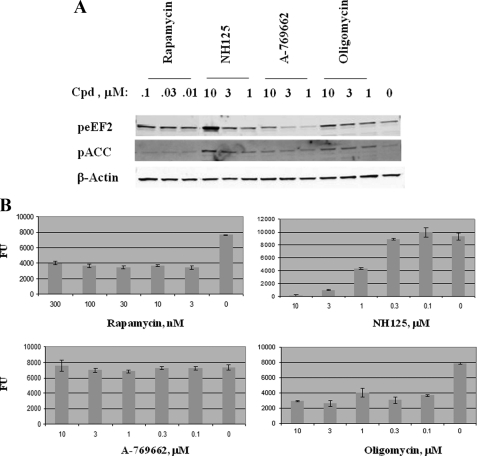

A few inhibitors are known to induce eEF2 phosphorylation. Rapamycin is known to bind to FKBP12 and form an inhibitory complex against mTORC1, leading to activation of the mTOR/S6K/eEF2K pathway (20). Two AMPK activators used in this study were A-769662, developed originally for type 2 diabetes indications (24), and oligomycin, known also to activate AMPK (21). Activation of AMPK will lead to induction of pACC, a substrate of AMPK. When PC3 cells were treated with rapamycin, NH125, A-769662, and oligomycin, eEF2 phosphorylation was increased to various degrees (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 1, β-actin was used as loading control because total ACC and eEF2 levels tracked well with β-actin in multiple experiments. The results showed that rapamycin induced peEF2 at concentrations as low as 0.01 μm. Thereafter, increasing concentrations of the drug only caused a modest increase of peEF2 levels. Because rapamycin only activates eEF2K-mediated eEF2 phosphorylation, the pACC level remained unchanged. Cells treated with NH125 showed a dose-dependent response of peEF2, which reached a high level equivalent to that of total nutrient deprivation in PC3 (Fig. 1B). Strong stimulation of pACC indicated that NH125 also activated the AMPK pathway. Meanwhile, A-769662 only weakly induced both peEF2 and pACC. Oligomycin, on the other hand, displayed a similar pattern of peEF2 induction to rapamycin. However, oligomycin also induced pACC, consistent with its known role in activation of the AMPK pathway.

FIGURE 4.

eEF2 phosphorylation correlates with growth inhibition. PC3 cells were treated with the indicated compounds at various concentrations for 6 h and processed for Western blot analysis (A). The membrane was probed with peEF2 and pACC antibodies (A). Because total eEF2 and ACC tracked well with β-actin, only β-actin was shown as the protein loading control. A parallel set of PC3 cells was treated with the compounds at the indicated concentrations for 3 days and subject to CyQuant NF analysis (B). Fluorescence units (FU) were graphed against compound concentrations. Error bar shows S.E. of the samples.

To assess the effect on growth, we treated PC3 cells with the compounds for 3 days and ran CyQuant NF analysis to measure cell growth (Fig. 4B). As the results showed, growth inhibition patterns for the compounds were strikingly similar to the patterns of their potencies on eEF2 phosphorylation. Rapamycin and oligomycin caused growth inhibition at low concentrations and reached a plateau of maximum inhibition around 60–70%. Like their effects on induction of peEF2, a further increase of drug concentrations showed little enhancement of growth inhibition. NH125, which had a strong dose-dependent induction of peEF2, also exhibited a strong dose-dependent growth inhibition. In contrast, A-769662, which induced very weak peEF2, exhibited little inhibition on the growth of PC3 cells. It is worth noting that growth inhibition only correlates with the level of eEF2 phosphorylation but not pACC, an indicator of the activation of the AMPK pathway.

NH125-induced eEF2 Phosphorylation Is Mediated through Multiple Pathways

In addition to the well established upstream kinase eEF2K, AMPK can also phosphorylate eEF2 independent of eEF2K (11, 12). To evaluate the roles of AMPK and eEF2K pathways in NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation, we used the eEF2K inhibitor A-484954, a widely used AMPK inhibitor compound C (Cpd C) (25), and another proprietary AMPK inhibitor compound A (Cpd A) developed by Abbott Laboratories (26). PC3 cells were treated with the compounds at the indicated concentrations for 6 h before Western blot analysis (Fig. 5). Because total ACC and eEF2 tracked well with β-actin, only β-actin was used to serve as a protein loading control. Basal levels of pACC and peEF2 are shown in lane 1. We first evaluated the role of each pathway on NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation. Inhibition of the AMPK pathway, either by Cpd A or Cpd C, only inhibited pACC but not peEF2 (lanes 2–4). Meanwhile, inhibition of the eEF2K pathway by A-484954 had little effect on either pACC or peEF2 (lane 5). As controls, the compounds alone showed little effect on the basal levels of pACC and peEF2. An exception was Cpd A, a strong AMPK inhibitor leading to reduction of basal pACC and peEF2 (lanes 6–8). Evidently, neither pathway inhibitor alone was able to block NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation. Next, we interrogated the combined effect of both pathways. The results showed that dual inhibition of the AMPK and eEF2K pathways inhibited pACC but only partially reduced eEF2 phosphorylation (lanes 9–12). These data suggest that NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation is mediated through multiple signaling pathways including but not limited to the eEF2K and AMPK pathways.

FIGURE 5.

NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation is mediated through multiple pathways. PC3 cells were treated with compounds at the given concentrations for 6 h and processed for Western blot analysis. Cpd A, Abbott AMPK inhibitor. Cpd C, AMPK inhibitor compound C.

DISCUSSION

In this study, exploration of eEF2K as an anticancer target uncovered an unidentified cellular mechanism of eEF2K inhibitor NH125. Contrary to conventional perception, inhibition of cancer cell growth by NH125 is correlated more with induction of eEF2 phosphorylation than inhibition of eEF2K. Additionally, data from the study raise a possibility that NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation may serve as a valuable marker to explore a multipathway mechanism for anticancer therapies.

The discovery of NH125 as an eEF2K inhibitor and an effective anticancer agent led to the proposition that the NH125-mediated anticancer effect was through inhibition of cellular eEF2K (16). Some recent studies showed that eEF2K also played a role in autophagy and survival in glioblastoma cells (9, 19). These novel findings implied that eEF2K was a valuable target for anticancer therapies. Generally, however, inhibition of eEF2K has not been able to achieve an efficacious anti-proliferation effect like NH125. Our data using eEF2K siRNA and a selective small molecule eEF2K inhibitor support the observations. Moreover, we find that NH125 actually induces eEF2 phosphorylation in cancer cells, which is the opposite of what an eEF2K inhibitor is expected to do. NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation is not due to small molecule inhibition of eEF2K because A-484954 inhibits peEF2 under the same conditions. Previously, another small molecule eEF2K inhibitor, TS2, was also shown to reduce peEF2 in v-src-transformed NIH3T3 cells (27). These data reveal that the anticancer effect of NH125 is not mediated through inhibition of eEF2K.

One of the interesting observations in this study is that the eEF2K and AMPK pathway-related compounds show a correlation between potencies to induce eEF2 phosphorylation and efficacy of their anti-proliferation effect. It is obvious from the data that inhibitors like rapamycin and oligomycin, which have limited enhancement on eEF2 phosphorylation, also exhibit limited inhibition on cancer cell growth. These compounds display a cytostatic effect over a wide range of concentrations. In contrast, NH125, a strong inducer of eEF2 phosphorylation, exhibits strong inhibition on the growth of cancer cells. In fact, correlation between compound-induced eEF2 phosphorylation and growth inhibition was reported previously. Lonafarnib, a farnesyltransferase inhibitor, and lopinavir, a HIV-1 protease inhibitor, were reported to induce eEF2 phosphorylation in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines and mouse myoblasts, respectively (12, 28). In the case of lonafarnib, growth inhibition was correlated to induction of peEF2 in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. The mechanism of lonafarnib-induced peEF2 was unidentified. The mechanism of lopinavir-induced peEF2 was attributed to activation of the AMPK pathway.

Preliminary data here suggest that NH125-induced eEF2 phosphorylation is mediated through multiple pathways. At least two pathways, the AMPK and eEF2K pathways, contribute to the increase of peEF2. What other pathways are involved remains unclear. Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) can also increase peEF2 (29). It was reported, however, that inhibition of PP2A activity favored cancer cell growth and tumor formation (30), which is inconsistent with the anticancer property of NH125. eEF2K is a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzyme. In enzymatic assays, inhibition of eEF2K by NH125 weakened as concentrations of calmodulin increased (Fig. 1C). The results suggested that NH125 might compete with calmodulin in some way. Calmodulin is important not only in eEF2K but also other cellular signal pathways (31, 32). If NH125 interferes with other calmodulin-dependent pathways, cancer cells treated with NH125 may produce unexpected patterns of eEF2 phosphorylation. Actually, we found that a calmodulin inhibitor, SKF-7171A, also induced eEF2 phosphorylation (data not shown). Unlike NH125, however, SKF-7171A does not activate the AMPK pathway. NH125 appears to be the first anticancer agent known to induce eEF2 phosphorylation through regulation of multiple pathways. It is likely that simultaneous disruption of multiple pathways is what makes NH125 a much more effective anticancer agent than rapamycin and oligomycin under the experimental conditions.

The observations here raise a new question: is phosphorylation of eEF2 directly responsible for growth inhibition or a reflection of multipathway activities? In either case, identification of the genes targeted by NH125 may provide a definitive answer. It is widely accepted that inhibition of multiple pathways offers more effective anticancer therapies than inhibition of a single target. One major challenge, however, is to identify the related genes and pathways that can offer effective anticancer activities. Phosphorylation of eEF2, therefore, can serve as an indicator not only for identification of the remaining NH125 pathways but also for discovery of efficacious NH125-like anticancer agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael R. Michaelides for examining chemical structures and proprietary issues and Daniel H. Albert and Andrew H. Judd for sharing the Abbott AMPK inhibitors and activators.

Footnotes

- eEF2

- eukaryotic elongation factor-2

- NH125

- 1-benzyl-3-cetyl-2-methylimidazolium iodide

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- MTS

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium

- pACC

- phospho-acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- Cpd

- compound C.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ryazanov A. G., Shestakova E. A., Natapov P. G. (1988) Nature 334, 170–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ryazanov A. G., Davydova E. K. (1989) FEBS Lett. 251, 187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nairn A. C., Palfrey H. C. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 17299–17303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ryazanov A. G. (2002) FEBS Lett. 514, 26–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Browne G. J., Proud C. G. (2002) Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 5360–5368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Browne G. J., Finn S. G., Proud C. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12220–12231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kahn B. B., Alquier T., Carling D., Hardie D. G. (2005) Cell Metab. 1, 15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Browne G. J., Proud C. G. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2986–2997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu H., Yang J. M., Jin S., Zhang H., Hait W. N. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 3015–3023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dorovkov M. V., Pavur K. S., Petrov A. N., Ryazanov A. G. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 13444–13450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hong-Brown L. Q., Brown C. R., Huber D. S., Lang C. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3702–3712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hong-Brown L. Q., Brown C. R., Huber D. S., Lang C. H. (2008) J. Cell. Biochem. 105, 814–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamamoto K., Kitayama T., Ishida N., Watanabe T., Tanabe H., Takatani M., Okamoto T., Utsumi R. (2000) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64, 919–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yamamoto K., Kitayama T., Minagawa S., Watanabe T., Sawada S., Okamoto T., Utsumi R. (2001) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65, 2306–2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pavur K. S., Petrov A. N., Ryazanov A. G. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 12216–12224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arora S., Yang J. M., Kinzy T. G., Utsumi R., Okamoto T., Kitayama T., Ortiz P. A., Hait W. N. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 6894–6899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arora S., Yang J. M., Utsumi R., Okamoto T., Kitayama T., Hait W. N. (2004) Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hait W. N., Wu H., Jin S., Yang J. M. (2006) Autophagy 2, 294–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu H., Zhu H., Liu D. X., Niu T. K., Ren X., Patel R., Hait W. N., Yang J. M. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 2453–2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomson A. W., Turnquist H. R., Raimondi G. (2009) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 324–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horman S., Browne G., Krause U., Patel J., Vertommen D., Bertrand L., Lavoinne A., Hue L., Proud C., Rider M. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1419–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burns D. J., Kofron J. L., Warrior U., Beutel B. A. (2001) Drug Discov. Today 6 (Suppl), 40–47 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen Z., Xiao Z., Gu W. Z., Xue J., Bui M. H., Kovar P., Li G., Wang G., Tao Z. F., Tong Y., Lin N. H., Sham H. L., Wang J. Y., Sowin T. J., Rosenberg S. H., Zhang H. (2006) Int. J. Cancer 119, 2784–2794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cool B., Zinker B., Chiou W., Kifle L., Cao N., Perham M., Dickinson R., Adler A., Gagne G., Iyengar R., Zhao G., Marsh K., Kym P., Jung P., Camp H. S., Frevert E. (2006) Cell Metab. 3, 403–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou G., Myers R., Li Y., Chen Y., Shen X., Fenyk-Melody J., Wu M., Ventre J., Doebber T., Fujii N., Musi N., Hirshman M. F., Goodyear L. J., Moller D. E. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1167–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson S. N., Cool B. L., Kifle L., Chiou W., Egan D. A., Barrett L. W., Richardson P. L., Frevert E. U., Warrior U., Kofron J. L., Burns D. J. (2004) J. Biomol. Screen 9, 112–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cho S. I., Koketsu M., Ishihara H., Matsushita M., Nairn A. C., Fukazawa H., Uehara Y. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1475, 207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Basso A. D., Mirza A., Liu G., Long B. J., Bishop W. R., Kirschmeier P. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31101–31108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Redpath N. T., Price N. T., Severinov K. V., Proud C. G. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 213, 689–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen W., Possemato R., Campbell K. T., Plattner C. A., Pallas D. C., Hahn W. C. (2004) Cancer Cell 5, 127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rodriguez-Mora O., LaHair M. M., Howe C. J., McCubrey J. A., Franklin R. A. (2005) Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 9, 791–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roderick H. L., Cook S. J. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 361–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]