Background: Autotaxin is essential for vascular development in mice, but the underlying mechanism remains unknown.

Results: Autotaxin had similar vascular functions in zebrafish. Furthermore, suppression of lysophosphatidic acid receptors (LPA1 and LPA4) led to similar vascular defects.

Conclusion: Autotaxin exerts its vascular functions by activating LPA1 and/or LPA4 in zebrafish.

Significance: LPA is a critical factor for regulating angiogenesis in vertebrates.

Keywords: Lysophospholipid, Vascular, Vascular Biology, Vasculogenesis, Zebra fish, G Protein-coupled Receptor, Autotaxin, Lysophosphatidic Acid, Vascular Formation, Zebrafish

Abstract

Autotaxin (ATX) is a multifunctional ecto-type phosphodiesterase that converts lysophospholipids, such as lysophosphatidylcholine, to lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) by its lysophospholipase D activity. LPA is a lipid mediator with diverse biological functions, most of which are mediated by G protein-coupled receptors specific to LPA (LPA1–6). Recent studies on ATX knock-out mice revealed that ATX has an essential role in embryonic blood vessel formation. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain to be solved. A data base search revealed that ATX and LPA receptors are conserved in wide range of vertebrates from fishes to mammals. Here we analyzed zebrafish ATX (zATX) and LPA receptors both biochemically and functionally. zATX, like mammalian ATX, showed lysophospholipase D activity to produce LPA. In addition, all zebrafish LPA receptors except for LPA5a and LPA5b were found to respond to LPA. Knockdown of zATX in zebrafish embryos by injecting morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (MOs) specific to zATX caused abnormal blood vessel formation, which has not been observed in other morphant embryos or mutants with vascular defects reported previously. In ATX morphant embryos, the segmental arteries sprouted normally from the dorsal aorta but stalled in midcourse, resulting in aberrant vascular connection around the horizontal myoseptum. Similar vascular defects were not observed in embryos in which each single LPA receptor was attenuated by using MOs. Interestingly, similar vascular defects were observed when both LPA1 and LPA4 functions were attenuated by using MOs and/or a selective LPA receptor antagonist, Ki16425. These results demonstrate that the ATX-LPA-LPAR axis is a critical regulator of embryonic vascular development that is conserved in vertebrates.

Introduction

Autotaxin (ATX)2 was first isolated as a cell motility-stimulating factor against malignant cancer cells from the culture cell supernatant of cancer cells (1). Subsequently, it was shown to be identical to a plasma enzyme, called lysophospholipase D, which is responsible for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) production in blood (2, 3). Both in vivo and in vitro, ATX converts lysophospholipids, such as lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), to LPA by its lysophospholipase D activity. ATX is produced and secreted by various cell types and is present in various biological fluids, including plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and seminal fluid (4). Recent studies have suggested that ATX accounts for the bulk LPA production in these fluids (5). In vitro, ATX acts on other substrates, such as sphingosylphosphorylcholine and nucleoside triphosphate, producing sphingosine 1-phosphate (6) and nucleotide monophosphate (7), respectively, although their Km values are much higher than those for lysophospholipids (2). LPA, a second generation lipid mediator, binds to its cognate G protein-coupled receptors, through which it affects various cellular processes, such as cell motility and cell proliferation (8). Recent studies on LPA receptor knock-out mice have revealed that LPA signaling through these LPA receptors has roles in a number of pathophysiological conditions, such as neural development, embryo implantation, neuropathic pain, and lung fibrosis (9–12).

ATX-null mice die around embryonic day 9.5–10.5 with profound vascular defects in both yolk sac and embryo and aberrant neural tube formation (5, 13, 14). In addition, mutated ATX knock-in, in which a single amino acid responsible for the catalytic activity of ATX was modified, was embryonically lethal, causing severe defects in the vasculature. These results have suggested that the product of ATX, possibly LPA, has a role in embryonic vascular formation (15). However, none of the LPA receptor knock-out mice have shown a similar phenotype (9, 10, 16, 17), and thus, it remains to be solved which LPA receptors are involved and how ATX regulates embryonic vasculature in the early developmental stages.

Zebrafish has been used as a genetic model organism for the analysis of vascular formation due to its simple vascular network during the early developmental stage (18). Furthermore, zebrafish embryos are optically clear and grow outside the mother, making it possible to examine vascular formation in live embryos (19). In zebrafish embryos, hemangioblasts trans-differentiate into endothelial cells to form the dorsal aorta (DA) and the posterior cardinal vein (PCV) 24 h postfertilization (hpf). Then the segmental arteries (SAs) begin to sprout bilaterally from the DA and grow dorsally following each vertical boundary between the somites, laterally to the notochord and to the neural tube. The SAs on each side of the trunk are joined together just dorsal to the neural tube by two separate dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels (DLAVs) (19). Analyses of vascular formation using mutants and antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) have identified a number of molecules involved in vasculature development, including growth factors, cell adhesion molecules, and transcription factors (18). These analyses have shown that the basic mechanisms of embryonic blood vessel formation are conserved in vertebrates.

A search of the database for sequences similar to mammalian ATX and LPA receptors found homologues only in vertebrates, including zebrafish (20). To elucidate the role of ATX and LPA signaling in vasculature formation, we tried to characterize these LPA-related genes both biochemically and functionally. Here we report biochemical and functional characterization of zebrafish ATX and LPA receptors and propose that the ATX-LPA axis has a key role in vasculature formation in the zebrafish embryo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

1-Lauroyl (12:0)-LPC, 1-myristoyl (14:0)-LPC, 1-palmitoyl (16:0)-LPC, 1-stearoyl (18:0)-LPC, 1-arachidoyl (20:0)-LPC, 1-oleoyl (18:1)-LPC, 1-oleoyl-LPE, 1-oleoyl-LPS, and 1-oleoyl-LPI were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL). 1-Linoleoyl (18:2)-LPC was from Doosan Serdary Research Laboratories (Kyungki-Do, Korea). Sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPC) was from Biomol Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Other chemicals were purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan).

Cloning of Zebrafish atx and LPA Receptors

Amino acid sequences of nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (NPP) families and LPA receptors from different species were identified from the National Center for Biotechnology Information data base. A phylogenic tree was made from the protein alignment by ClustalW and then visualized using FigTree version 1.3.1 (available on the World Wide Web). The total RNAs were isolated from zebrafish embryos using the GenElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich), and cDNA libraries were synthesized with a high capacity cDNA RT kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). cDNA for full-length zebrafish ATX was amplified by nested PCR using zebrafish cDNA libraries as template DNA. The resulting DNA fragments were subcloned into pBluescript vector (zATX-pBS). cDNA for full-length zebrafish ATX was amplified by PCR using zATX-pBS as a template DNA and subcloned into EcoRI and XhoI sites of pCAGGS-MCS-myc vector (zATX-myc-pCAGGS). pCAGGS-MCS-myc was modified from original pCAGGS vector (kindly donated by Dr. Junichi Miyazaki, Osaka University (21)) by introducing the multiple restriction sites (SacI, SmaI, KpnI, EcoRI, EcoRV, NotI, and XhoI) followed by DNA sequence encoding the c-Myc tag. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to prepare the cDNA encoding enzymatically inactive zATX (T205A) using zATX-myc-pCAGGS as a template DNA. cDNA for full-length zebrafish LPA receptors was amplified by nested PCR using cDNA libraries from zebrafish embryos as a template DNA. The resulting DNA fragments were subcloned into EcoRV and KpnI sites of pCAGGS-FLAG-MCS vector. pCAGGS-FLAG-MCS was modified from original pCAGGS vector by introducing the DNA sequence encoding FLAG tag followed by multiple restriction sites described above. The sequences of oligonucleotides used for cloning are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Preparation of Recombinant Zebrafish ATX Protein

HEK293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 1 mm l-glutamine. zATX-myc-pCAGGS and zATX (T205A)-myc-pCAGGS were transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. After a 24-h incubation, medium was changed to serum-free DMEM, and the cells were further cultured for 48 h. Then cell culture supernatant was harvested and concentrated (100-fold) using an Amicon Ultra-15 filter device (30,000 nominal molecular weight limit membrane, Millipore (Bedford, MA)). The protein concentration was determined with the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Generation of Antibody against Zebrafish ATX

A recombinant protein corresponding to amino acids 160–336 of zebrafish ATX was expressed in Escherichia coli as a GST fusion protein using the pGEX-4T1 vector (GE Healthcare). The protein was purified using GSH-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's protocol and used to immunize rats (WKY/Izm strain) (SLC, Shizuoka, Japan) with Freund's complete adjuvant (Wako, Osaka, Japan). Seven days after the final immunization boost, the rats were bled, and the antiserum was prepared.

Western Blotting

Embryos were deyolked as described previously (22) with slight modifications. Briefly, 30 embryos at 48 hpf were dechorionized with forceps and transferred to a 1.5-ml tube. After removing excess water, 200 μl of deyolking buffer (55 mm NaCl, 1.8 mm KCl, 1.25 mm NaHCO3) were added, and the yolk sac was disrupted by pipetting with a 200-μl yellow tip (739296, Greiner Bio-one (Monroe, NC)). The embryos were shaken for 5 min with a direct mixer at room temperature (DM-301, AS ONE Corp.), followed by centrifugation at 300 × g for 30 s. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was washed with 1 ml of wash buffer (110 mm NaCl, 3.5 mm KCl, 2.7 mm CaCl2, 10 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.5). SDS-PAGE was performed according to Laemmli's method. The following dilutions of primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting: anti-Myc mAb 9E10 (1:100) and anti-zATX antiserum (1:2000). Proteins bound to the antibody were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL, GE Healthcare).

Biochemical Characterization of Zebrafish ATX

To study the effects of the fatty acyl chain moiety of LPC on the enzymatic activity of ATX, recombinant mouse ATX and zATX (0.2 μg/ml) proteins were mixed with 2 mm LPC (12:0, 14:0, 16:0, 18:0, 18:1, 18:2, or 20:0) in a buffer containing 500 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), and 0.05% Triton X-100 and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The amount of free choline liberated was determined colorimetrically using choline oxidase (Wako, Osaka, Japan), peroxidase (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan), and TOOS reagent (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) as described (2). The SPC-hydrolyzing activity was determined by incubating recombinant ATX protein (0.2 μg/ml) with 2 mm SPC and measuring the liberated choline as described above. To study the effects of the polar headgroup of lysophospholipids on the enzymatic activity of ATX, recombinant mouse or zebrafish ATX (1.0 μg/ml), proteins were mixed with 2 mm 18:1 LPC, LPE, LPS, or LPI in the buffer containing 500 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, and 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) in the presence of 0.05% Triton X-100 and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The amount of LPA generated was determined by the colorimetric method as described previously (23). To measure phosphodiesterase activity, recombinant mouse or zebrafish ATX (0.2 μg/ml) proteins were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in a buffer containing 500 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 0.05% Triton X-100, and 4 mm p-nitrophenyl thymidine 5-monophosphate (pNP-TMP; Sigma), and production of p-nitrophenol was analyzed by measuring the optical density at 405 nm. The Km and Vmax values for 14:0 LPC and pNP-TMP for each substrate were determined using the Lineweaver-Burk plot as illustrated in Fig. 1, E and F. The catalytic activity of zebrafish ATX against physiological substrates was determined as described previously (24). Briefly, ATX-depleted mouse plasma was prepared using anti-mouse ATX monoclonal antibodies coupled to Sepharose 4B as described (25) and incubated with recombinant zATX (10 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 6 h. Production of various LPA species during the incubation was determined by LC-MS/MS as described previously (24).

FIGURE 1.

Zebrafish ATX is a potent LPA-producing enzyme. A, domain structures of human and zebrafish ATXs. The amino acid identity of each domain is indicated. B and C, lysophospholipase D activity of recombinant zebrafish ATX. HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmid DNA encoding C-terminally Myc-tagged wild-type (zATX-myc-pCAGGS) and mutant ATX (zATX (T205A)-myc-pCAGGS). Secreted ATX in the conditioned medium (B) was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (9E10). Lysophospholipase D activity of wild-type (Wt) and mutant zebrafish ATX (T205A) (C) was analyzed using 1-myristoyl lysophosphatidylcholine as a substrate. D, nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity of mouse and zebrafish ATX, using p-nitrophenol-TMP as a substrate. E and F, phosphodiesterase activities of zebrafish ATX against LPC (E) and pNP-TMP (F) were examined with the indicated concentrations of substrates. Inset, Lineweaver-Burk plot to calculate Km and Vmax values. Error bars, S.D.

Cell Migration Assay

Cell migration was measured in a modified Boyden chamber as described previously (26). Briefly, polycarbonate filters with 8-μm pores (Neuro Probe, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) were coated with 0.001% (w/v) fibronectin (Sigma). Recombinant ATX and cells were prepared in the same buffer (serum-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% (w/v) BSA). The recombinant ATX and the cells (3 × 105 cells in 200 μl/well) were loaded into the lower and upper chambers, respectively. After an incubation at 37 °C for 3 h to allow migration, the cells on the filter were stained with a Diff-Quick staining kit (International Reagent Co., Kobe, Japan). The number of cells that migrated to the bottom was determined by measuring the optical density at 590 nm, using a microplate reader (VersaMax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Maintenance of Zebrafish

Wild-type AB strain, transgenic (Tg) (fli1:EGFP) strain, and Tg (fli1:nEGFP) strain were obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (University of Oregon, Eugene, OR). Fish were maintained at 27–28 °C under a controlled 13.5-h light/10.5-h dark cycle. Embryos were obtained from natural spawnings and staged according to morphology as described (27).

Morpholino Injection

The following doses were injected per embryo in the described experiments: ATX 5-mismatch MO1, 2.5 ng; ATX MO1, 2.5 ng; ATX MO2, 16 ng; LPA1 MO, 8 ng; LPA2a MO, 2 ng; LPA2b MO, 4 ng; LPA3 MO, 16 ng; LPA4 MO, 4 ng; LPA5a MO, 4 ng; LPA5b MO, 2 ng; LPA6a MO, 16 ng; and LPA6b MO, 4 ng. MOs were dissolved in water with 0.2% phenol red. The sequences of MOs (Gene Tools, LLC, Corvalis, OR) were as follows: ATX MO1, 5′- GGAGAATACCTGGGTCGAGACACCG-3′; ATX 5-mismatch MO1, 5′- GGAcAATAgCTGcGTCcAGACAgCG-3′; ATX MO2, 5′- TTCTTTCAAAGTCCCTACCTTTGCA-3′; LPA1 MO, TGGAGCACTTACCCAATACAATCAC (28); LPA2a MO, CCAGCCCTAAAACACAGGAAGACAT; LPA2b MO, CTGATCTACAAGGAGAATATCACAC; LPA3 MO, ATGTAAAGCAGTAATCTCACCTAGC; LPA4 MO1, GGCCATTTTGGCACTTGCAGTAGAT; LPA4 MO2, ACTCCTGTTTCCAGTTAATTTCCGA; LPA5a MO, TCCAAAGAGACTGGTGTGTTTAAGA; LPA5bMO, TTCTCTCAAGAAAACGAATCGACGT; LPA6a MO, TCTTAACAACAGACAAAGGCACGCT; LPA6b MO, TTTGGCTTAAAACACAGTGAGTGTA.

The effect of splice-blocking MO was evaluated by RT-PCR analysis using the oligonucleotides listed in supplemental Table 2. The effect of translation-blocking MO was evaluated by injecting MO with mRNA encoding EGFP downstream of the 5′-UTR sequence of target gene. The 5′-UTR sequences of each target gene constructed in this study were as follows: LPA4, TCGGAAATTAACTGGAAACAGGAGTACATCTACTGCAAGTGCCAAA; LPA5a MO, TCTTAAACACACCAGTCTCTTTGGAAA; LPA5b MO, ACGTCGATTCGTTTTCTTGAGAGAA; LPA6a MO, AGCGTGCCTTTGTCTGTTGTTAAG; LPA6b MO, TACACTCACTGTGTTTTAAGCCAAAAGAATCATTG.

Evaluation of LPA Receptor Activation

Activation of LPA receptor was evaluated by a TGF-α shedding assay as described previously (29). Briefly, each zebrafish LPA receptor gene was introduced into HEK 293 cells together with DNA encoding TGF-α fused to alkaline phosphatase. Upon the addition of a ligand for LPA receptors, the TGF-α proform expressed on the plasma membrane was cleaved by TACE proteases endogenously expressed in HEK293 cells and thereby released into the culture medium. Then the activation of LPA receptor was evaluated by measuring the alkaline phosphatase activity in the conditioned medium of the cells.

Whole Mount in Situ Hybridization

An antisense RNA probe labeled with digoxigenin for atx was prepared with an RNA labeling kit (Roche Applied Science). Whole mount in situ hybridization was performed as described previously (30).

Microscopic Analysis and Live Imaging

Embryos were embedded in a drop of 0.7% low melting point agarose containing 0.01% Tricaine and 0.003% 1-phenyl-2-thiourea. Temperature was kept at ∼28.5 °C. Images were captured with a LSM 700 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

RESULTS

Autotaxin Is Biochemically Conserved in Zebrafish

A database search identified a gene of zgc:63550 as a putative autotaxin (atx)/npp2 gene in zebrafish. zgc:63550 encoded a protein of 850 amino acids, containing two somatomedin B-like domains, a catalytic domain, and a nuclease-like domain (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. 1A). The amino acid sequence of zgc:63550 shows 67.1% identity to that of human ATX (supplemental Fig. 1A and Fig. 1A). zgc:63550 belongs to the NPP family and phylogenetically clusters with mouse and human atx/npp2 (supplemental Fig. 1B). When the open reading frame encoded by the clone was subcloned into a mammalian expression vector and the cDNA was transfected into HEK293 cells, recombinant protein was successfully released into the culture medium and showed significant lysophospholipase D activity (Fig. 1, B and C). zgc:63550 with the mutation at the predicted catalytic center (T205A) expressed in HEK293 cells was also recovered in the culture medium without enzymatic activity (Fig. 1, B and C), confirming that T205 is the catalytic center of zgc:63550 and that the catalytic machinery is conserved in zgc:63550. These observations indicate that zgc:63550 is an orthologue of atx/npp2 in zebrafish. Accordingly, we designated it zATX. Notably, zATX hydrolyzed nucleotide substrate pNP-TMP much less efficiently than mouse ATX (Fig. 1D). In addition, the obtained kinetic parameters (Km and Vmax) obtained from Lineweaver-Burk plots (Fig. 1, E and F) showed that LPC is a far better substrate than pNP-TMP (Table 1). We further examined the substrate selectivity of zATX using lysophospholipid substrates with different headgroups and acyl chains. zATX preferably hydrolyzed LPC and lysophosphatidylethanolamine but did not efficiently hydrolyze lysophosphatidylserine, lysophosphatidylinositol, or sphingosylphosphorylcholine (Fig. 2, A and B). Among LPC species with different carbon chain lengths and different degrees of saturation that we tested, LPCs with shorter and more unsaturated acyl chains were the preferred substrates of zATX, as was the case with mammalian ATX. The rank order was 12:0 > 14:0 > 16:0 ≫ 18:0 > 20:0 among the saturated fatty acyl LPCs and 18:2 > 18:1 ≫ 18:0 among LPCs with an 18-carbon acyl chain (Fig. 2B). To further explore the substrate specificity under more physiological conditions, recombinant zATX protein was added to ATX-depleted mouse plasma, and the LPA species produced during incubation at 37 °C was determined using mass spectrometry. zATX mainly produced 18:2, 16:0, 18:1, 20:4, and 22:6 LPA, which are also produced by recombinant mouse ATX (Fig. 2C), confirming that the preference for unsaturated lysophospholipids of mammalian ATX (3, 24) is conserved in zATX. We also tested the cell motility-stimulating activity of zATX and found that zATX promoted the motility of tumor cells in an LPA receptor-selective antagonist (Ki16425)-sensitive manner (Fig. 3). Together, these results demonstrate that zATX has LPA-producing properties similar to those of mammalian ATX.

TABLE 1.

Specificity of zebrafish ATX for LPC and pNP-TMP

| Substrate | Km | Vmax |

|---|---|---|

| mm | nmol/μg/min | |

| LPC | 0.17 | 1.86 |

| pNP-TMP | 336 | 8.66 |

FIGURE 2.

Substrate specificity of ATX is conserved between mouse and zebrafish. A, effects of the polar headgroup of lysophospholipids on the enzymatic activity of ATX. 1-oleoyl-LPE, -LPS, -LPI, and -LPC were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h in the presence of zebrafish or mouse ATX. The amount of LPA produced was quantified by an enzyme-linked colorimetric method. B, substrate specificity of zebrafish and mouse ATX for LPC with a variety of fatty acids and SPC. LPC- and SPC-hydrolyzing activities were measured in the presence of 0.05% Triton X-100. C, catalytic activity of mouse and zebrafish ATX against physiological substrates. Recombinant mouse and zebrafish ATX were incubated in ATX-depleted plasma prepared using anti-mouse ATX monoclonal antibodies. The amount of LPA produced by recombinant ATX was measured by mass spectrometry. Error bars indicate the S.D. of the mean.

FIGURE 3.

Zebrafish ATX stimulates the cell motility. Cell motility-stimulating activities of recombinant zebrafish ATX. Zebrafish ATX recombinant protein promoted the motility of MDA-MB-231 cells in a Ki16425-sensitive manner. Error bars, S.D.

Autotaxin Is Required for the Development of Intersegmental Arteries in Zebrafish

We examined the expression of zATX during embryogenesis. zATX mRNA, as judged by RT-PCR, was detected as early as 12 hpf, and its level dramatically increased after 48 hpf (Fig. 4A). At 30 hpf, zATX mRNA, as measured by whole mount in situ hybridization, was found to be expressed in the head region (Fig. 4, B and C), the neural tube, the dorsal aorta (DA), and the posterior cardinal vein (PCV) (Fig. 4, B′ and C′). For knockdown analysis, we designed two splice-blocking MOs, MO1 and MO2 (supplemental Fig. 2A). RT-PCR analysis confirmed that ATX MO1 caused exon 2 to be skipped, leading to shortened transcripts (supplemental Fig. 2B). In contrast, ATX MO2 caused aberrant RNA splicing, resulting in a 14-bp deletion in the 3′-terminal sequence of exon 4 (supplemental Fig. 2C). Western blotting analysis by using anti-zATX polyclonal antibody confirmed the knockdown of zATX protein in embryos treated with either ATX MO1 or ATX MO2 but not in embryos treated with control ATX MO (ATX MO1-5mis) (Fig. 5A). Embryos injected with ATX MO1 showed edema (Fig. 5, B and C) and severely reduced blood flow (supplemental Movie 1). Embryos injected with ATX MO2 were similarly affected (data not shown). In contrast, blood flow in the uninjected embryos was vigorous (supplemental Movie 2). Notably, horizontal blood cell flow, possibly in the DA and the PCV, was observed in both ATX MO-injected and uninjected embryos (supplemental Movies 1 and 2) although much less in ATX MO-injected embryos. By contrast, vertical blood cell flow, possibly through intersegmental vessels (ISVs), was observed in uninjected embryos but not in ATX MO-injected embryos, suggesting that ISV formation is impaired in the ATX morphant embryos (supplemental Movies 1 and 2). We thus utilized the fli1:EGFP Tg line, in which endothelial cells were labeled with EGFP under the control of the fli1 promotor, to visualize blood vessel formation more precisely. Endothelial cells of the SAs as well as the DA and the PCV were specified in both the control (ATX MO1-5mis) and ATX morphant embryos, as judged by the EGFP expression in Tg (fli1:EGFP) (Fig. 5, D–F). In uninjected or control MO-injected embryos, the SAs reached the dorsal side of the neural tube, and the DLAVs were completely formed by 48 hpf (Fig. 5D). By contrast, in about 60% of the ATX MO1-injected embryos and about 40% of the ATX MO2-injected embryos, the SAs stalled in midcourse and aberrantly connected to the neighboring ISVs around the horizontal myoseptum (Fig. 5, E–G). Time lapse imaging showed that in both the control and ATX morphant embryos, the SAs sprouted from the DA and properly extended up to the horizontal myoseptum by 30 hpf (Fig. 5, H and I). In control embryos, the SAs further extended to the dorsal side of the neural tube and formed the DLAVs by 36 hpf and were fully lumenized by 42 hpf (Fig. 5H and supplemental Movie 3). By contrast, in ATX morphant embryos, the SAs stalled at the horizontal myoseptum and did not form the DLAVs by 36 hpf, and then the SAs extended in abnormal directions and connected to the neighboring SA (Fig. 5I and supplemental Movie 4). When fli1:nEGFP transgenic embryos, which express EGFP protein in the nucleus of endothelial cells, were injected with ATX MO1, two or three endothelial cells formed each SA, which is comparable with the number in control embryos (Fig. 5, J and K). This suggests that the aberrant vascular network in ATX morphant embryos is not due to abnormal proliferation of endothelial cells. Because endothelial cells are differentiated and specified in ATX morphant embryos, ATX may have a role in some processes of vascular formation other than cell proliferation or differentiation. One possibility is that ATX facilitates angiogenesis by inducing the SA migration from the horizontal myoseptum to the dorsal side of the trunk of zebrafish embryos.

FIGURE 4.

Expression pattern of zebrafish ATX gene at stage of development. A, ATX mRNA expression at the indicated times postfertilization, as measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Values are normalized to the expression level of elfa1 mRNA. Error bars indicate the S.D. of the mean. B and C, whole mount in situ hybridization analyses with antisense (B and B′) and sense (C and C′) probes of atx at 30 hpf. ATX mRNA is expressed in the head region (arrow), the neural tube (N), and the vasculature (V) including the DA and the PCV at 30 hpf. Lateral views, anterior to the left. Scale bar, 50 μm.

FIGURE 5.

Zebrafish ATX is important for the segmental artery development. A, Western blot analysis using an antibody against zebrafish ATX. Embryos were injected with the indicated MO. Embryo lysates were prepared at 48 hpf. Tubulin expression was used as a loading control. B and C, effects of ATX morpholino. As compared with uninjected embryos (B), embryos injected with ATX MO1 (C) caused edema in heart and head regions (arrows). D–F, confocal images of fli1:EGFP embryos at 48 hpf. Lateral views, anterior to the left. In embryos injected with control MO (D), the SAs extended from the DA and formed the DLAVs. In contrast, in ATX MO1-injected embryos (E) and ATX MO2-injected embryos (F), the SAs stalled around the horizontal myoseptum (asterisk) and aberrantly connected to the neighboring ISV (arrowheads). Dotted lines, dorsal edge of the embryos. G, graph representing the percentage of embryos with aberrant ISV connection around the horizontal myoseptum at 48 hpf (n = 31–35; ***, p < 0.001 by χ2 test). H and I, confocal time lapse analysis of fli1:EGFP embryos from 30 to 42 hpf. Control embryos show the normal SA sprouts (H). By contrast, in ATX morphant embryos, the ISV initially stalled around the horizontal myoseptum at 34 hpf (asterisk) and connected the neighboring ISV abnormally at 42 hpf (arrowhead) (I). J and K, confocal images of fli1:nEGFP embryos at 32 hpf. Each SA consists of two or three endothelial cells both in control (J) and ATX morphant embryos (K). Scale bar, 50 μm.

Characterization of LPA Receptors in Zebrafish

To investigate the LPA signaling involved in ATX-mediated embryonic vasculature, we next examined the roles of each LPA receptor in vascular formation in zebrafish embryos. To this end, we first characterized the zebrafish homologues of LPA receptors biochemically. A zebrafish data base search for nucleotide sequences similar to mammalian LPA receptors found multiple homologues for each LPA subtype. Of note, we found two homologues of LPA2 (zgc:101053 and zgc:123246), LPA5 (zgc:66034 and NM001128797), and LPA6 (zgc:153784 and ENSDARG00000069441), which probably arose from the whole genome duplication that occurred in the teleost fish lineage. Phylogenic analysis of the LPA receptors clearly shows that zebrafish LPA1–3 and LPA4–6 belong to the Edg receptor and P2Y receptor families, respectively (supplemental Fig. 3B). Of note, each zebrafish LPA receptor homologue clusters with mouse and human counterparts, indicating that it is the zebrafish orthologue. LPA stimulated the release of TGF-α in a dose-dependent manner in HEK293 cells expressing each zebrafish LPA receptor homologue except for LPA5a and LPA5b (Fig. 6). An LPA1–3 receptor antagonist, Ki16425 (31), was found to antagonize LPA1, LPA2a, LPA2b, and LPA3 but not other zebrafish LPA receptors belonging to the P2Y receptor family (LPA4, LPA6a, and LPA6b) (Fig. 7). These results indicate that the manner of ligand recognition of LPA receptors was well conserved in vertebrate evolution.

FIGURE 6.

Responses of LPA receptor homologues in zebrafish. Each LPA receptor was transfected into HEK293 cells, and the amount of TGF-α released upon LPA stimulation was measured. The LPA response was observed in all LPA receptor homologues except for LPA5a or LPA5b. Error bars indicate the S.D. of the mean.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibitory effects of Ki16425 on the activation of LPA receptor homologues in zebrafish. Ki16425 inhibited the activation of LPA1, LPA2a, LPA2b, and LPA3 but not the activation LPA4, LPA6a, or LPA6b upon LPA stimuli.

Redundant LPA1 and LPA4 Signaling Mainly Directs Elongation of Segmental Artery in Zebrafish

To identify the LPA receptor(s) involved in vascular formation in zebrafish, we examined the effects of MOs against each LPA receptor. In addition to the LPA1 MO (28), we newly designed splice-blocking MOs that successfully interfere with the mRNA splicing of LPA2a, LPA2b, or LPA3 genes (supplemental Fig. 4, A–D). Furthermore, we made translation-blocking MOs that target the 5′-UTR sequence of LPA4, LPA5a, LPA5b, LPA6a, or LPA6b. Each MO was confirmed to inhibit the translation of the EGFP gene downstream of the 5′-UTRs of each of the LPA genes (supplemental Fig. 4, E–I). In embryos injected with a single MO for each LPA receptor (LPA1, LPA2a, LPA2b, LPA3, LPA4, LPA5a, LPA5b, LPA6a, or LPA6b), the SA formation appeared to be normal. In a small fraction (∼10%) of the LPA1 morphant embryos, the SA formation stalled around the myoseptum by 48 hpf (Fig. 8A). In addition, abnormal connections between neighboring ISVs around the horizontal myoseptum were observed in ∼12% of the embryos injected with LPA1 or LPA2b MO by 48 hpf (Fig. 8M) but only rarely in embryos injected with either of the other MOs (Fig. 8, C, D, and M, and supplemental Fig. 5A).

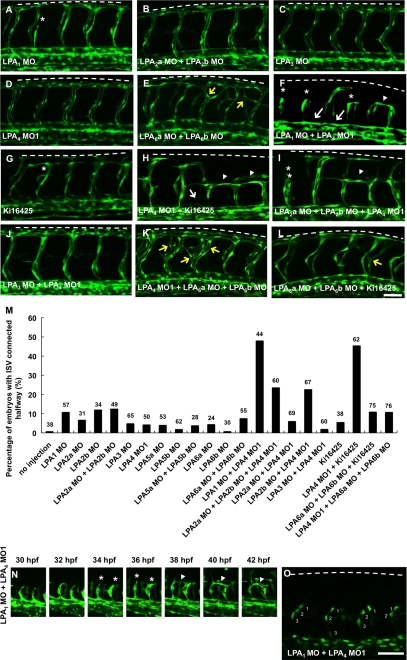

FIGURE 8.

LPA1 and LPA4 are important for segmental artery development. Confocal images of fli1:EGFP embryos at 48 hpf. Lateral views, anterior to the left. Embryos were treated with MOs or 120 μm Ki16425 dissolved in 1% DMSO. Embryos treated with LPA1 (A), LPA2a/LPA2b (B), LPA3 (C), LPA4 (D), LPA3/LPA4 (J) MOs and Ki16425 (G) showed almost normal ISV sprouts, except for a few SAs that stalled around the horizontal myoseptum (asterisks) in embryos treated with LPA1 MO and Ki16425. Embryos treated with LPA1/LPA4 (F) and LPA2a/LPA2b/LPA4 (I) MOs and LPA4 MO with Ki16425 (H) displayed the vascular phenotype of abnormal connection between neighboring ISVs (arrowheads in F, H, and I). Embryos treated with LPA6a/LPA6b (E) and LPA4/LPA6a/LPA6b (K) MOs and LPA6a/LPA6b MOs with Ki16425 (L) showed ISV branching (yellow arrows). Embryos treated with LPA1/LPA4 MOs (F) and LPA4 MO with Ki16425 (H) also showed the dissociation between SA and DA (arrows). M, percentage of embryos with aberrant ISV connections around the horizontal myoseptum at 48 hpf (n = 24–76). N, confocal time lapse analysis of fli1:EGFP embryos injected with LPA1/LPA4 MOs from 30 to 42 hpf. ISVs initially stalled around the horizontal myoseptum at 34 hpf (asterisk) and connected to the neighboring ISVs abnormally at 42 hpf (arrowhead). O, confocal images of fli1:nEGFP embryos injected with LPA1/LPA4 MOs at 32 hpf. Each SA consists of two or three endothelial cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. Numbers 1–3 indicate the number of endothelial cells in one ISV.

Because the vascular phenotype in each LPA receptor morphant embryo was far less severe than the vascular defects in ATX morphant embryos, we next examined the possibility that each LPA receptor redundantly functions in vascular development by treating embryos with two or three MOs targeting different LPA receptors. Vascular phenotype was not significantly induced by co-injection of LPA2a/LPA4, LPA3/LPA4, or LPA4/LPA6a/LPA6b MOs (Fig. 8, J, K, and M). However, the number of embryos with abnormal vascular connections between neighboring ISVs around the myoseptum synergistically increased in LPA1/LPA4 double morphant embryos as compared with the LPA1 or LPA4 single morphant embryos (Fig. 8, F and M, and supplemental Fig. 5B). Notably, the vascular defects of LPA1/LPA4 double morphant embryos were quite similar to those of ATX morphant embryos (Figs. 5, E and F, and 8F). Using time lapse imaging analysis, we confirmed that treatment with LPA1/LPA4 double MOs induced the stalling of the SAs at the myoseptum around 36 hpf. This was followed by the formation of an abnormal connection between neighboring ISVs by 40 hpf without affecting cell proliferation of endothelial cells of SAs, similar to the phenotype in ATX morphant embryos (Figs. 5 (I and K) and 8 (N and O) and supplemental Movie 5). By contrast, the number of embryos with abnormal vascular connections was additively increased in LPA2b/LPA4 double and LPA2a/LPA2b/LPA4 triple morphant embryos as compared with the LPA2a, LPA2b, or LPA4 single morphant embryos or LPA2a/LPA2b double morphant embryos (Fig. 8, I and M). To address the contribution of each LPA1 or LPA2b signaling in combination with LPA4 signaling in the SA development, we initially injected embryos with three MOs against LPA1/LPA2b/LPA4. However, the injected embryos displayed severe morphological defects, possibly due to the off target effects of each MO (data not shown). Thus, we next treated LPA4 morphant embryos with the LPA receptor antagonist, Ki16425, which was found to be effective for zebrafish LPA receptors, LPA1, LPA2a, LPA2b, and LPA3 (Fig. 7). The number of embryos with an abnormal connection between neighboring ISVs was higher in embryos treated with LPA4 MO and Ki16425 than in embryos treated with Ki16425 alone or LPA4 single, LPA2a/LPA4 double, or LPA2a/LPA2b/LPA4 triple MOs (Fig. 8, D, G, H, and M). The increase was similar to that observed in the LPA1/LPA4 double morphants. Taken together, these results suggest that LPA signaling mediated by LPA1 and LPA4 has major roles in the SA development and function redundantly downstream of ATX, whereas LPA2b signaling has minor roles compensating for the LPA1 signaling in the SA development. Interestingly, LPA6a/LPA6b double morphant embryos displayed abnormal branching of SA without any defects in the DLAV formation (Fig. 8, E and K), suggesting the specific role of LPA6a and LPA6b in vascular formation.

DISCUSSION

LPA-related genes, such as receptors, producing enzymes, and degrading enzymes, are highly conserved in vertebrates (20). In this study, we analyzed a zebrafish LPA-producing enzyme (ATX) and LPA receptors and found that both biochemical properties and biological functions are conserved between mammals and zebrafish. Both mammalian ATX and zATX produce LPA, especially LPAs with unsaturated fatty acyl chains, and stimulated cell motility of human cancer cells, although the phosphodiesterase activity of zATX toward a nucleotide substrate (pNP-TMP) was much weaker. Recent crystal structural analysis of mouse and rat ATX demonstrated the presence of a substrate pocket located in the vicinity of the catalytic center (24). Considering the fact that the amino acid residues forming the pocket are highly conserved between mammalian and zebrafish ATX, it is reasonable to assume that zATX functions as an LPA-producing enzyme. We also showed that all zebrafish LPA receptor candidates except LPA5 homologues (LPA5a and LPA5b) responded to LPA. Both human LPA5 and mouse LPA5 were activated by LPA in this system (data not shown). Compared with other zebrafish LPA receptors, which show about 60–70% amino acid identities to the corresponding mammalian counterparts, LPA5a and LPA5b show only 30% amino acid identities to mammalian LPA5 with much shorter C-terminal cytoplasmic tails (supplemental Fig. 3A). This may explain why zebrafish LPA5 homologues (LPA5a and LPA5b) did not respond to LPA.

Like ATX-deficient mice (5, 13), ATX morphant zebrafish embryos showed severe vascular defects. Thus, ATX appears to have a similar role in developing embryonic blood vessels in a wide range of vertebrates. In addition, the phenotypic similarity between the ATX morphant embryo and the LPA1/LPA4 double morphant embryo and the synergistic effects between LPA1 and LPA4 MOs on vascular formation suggest that the ATX-LPA axis is essential for embryonic vascular formation. In mice, LPA4 deficiency caused hemorrhage in embryos and was lethal for some embryos (17), whereas LPA1 deficiency caused frontal hematoma in a small fraction of embryos and occasionally death in neonates (9). Thus, the vascular phenotypes in these two LPA receptor-deficient embryos are much less severe than those in ATX-deficient embryos. The finding that the vascular phenotype of LPA6a/LPA6b morphant embryos was different from that of LPA1/LPA4 morphant embryos raises the possibility that the signaling pathways and functions of LPA6 are different from those of LPA1 and LPA4 in zebrafish. This hypothesis is partially supported by recent reports that LPA1 and LPA6 couple to Gi and G12/13, respectively, in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, which express LPA1, LPA4, and LPA6 (32, 33). It is necessary to further investigate the G protein that couples to LPA4 and signaling pathway downstream of LPA1, LPA4, and LPA6 to elucidate the roles of each LPA receptor signaling in zebrafish SA development.

Recent studies using zebrafish have clarified the functions of genes or signaling pathways required for the SA development. These include VEGF/VEGFR, Semaphorine/Plexin, Netrin, and Dll4/Notch signaling pathways and their components (34–37). It is noteworthy that the phenotypes observed in ATX or LPA1/LPA4 double morphant embryos were quite different from previously characterized vascular phenotypes. For example, angiogenic sprouting is severely impaired in the vegfr2 mutant (34) and angiogenic sprouting occurs ectopically in the plexin D1 mutant (35). In addition, the ISVs take on a plexus-like organization in the plexin D1 mutant because angiogenic sprouts did not avoid the ventral somites (35). Knockdown of Netrin-1a (36) or its receptor Unc5b (37) resulted in excessive branching of the ISVs. In the absence of Notch signaling, sprouting of the SA was excessive, whereas Notch activation suppresses angiogenesis from the DA. Knockdown of VE-cadherin, the major endothelial adhesion molecule, resulted in aberrant vascular connections and fusions. These vascular defects were not observed in ATX or LPA1/LPA4 double morphants (Figs. 5 (E–G) and 8 (F and M)). Thus, LPA signaling mediated by ATX-LPA1/LPA4 can be a novel pathway regulating formation of the vascular network. Recent studies have shown that a sprouting SA is composed of an endothelial tip cell and stalk cells, which follow the tip cell and proliferate. The tip cell extends the filopodia and migrates in response to angiogenic factors, such as VEGF. In the ATX morphant embryos, the tip cells and stalk cells initially behaved normally to form an SA, but then extension of the SA stopped, resulting in the malformation of the ISV (Fig. 5, H–K). It is thus possible that the tip and stalk cells are the targets of LPA. The fact that human umbilical vein endothelial cells express LPA1, LPA4, and LPA6 supports this idea. Formation of the embryonic vasculature is regulated by the activities of endothelial cells (including tip and stalk cells), such as their proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, and migration (38).

It is not known how ATX and LPA regulate formation of the vasculature. One possibility is that LPA stimulates the migration of endothelial cells, especially tip cells, because LPA is known to support migration of a number of cell types including endothelial cells through activation of LPA1 (39). ATX mRNA was significantly expressed in the neural tube (Fig. 4B′), to which the SAs appeared to extend, supporting the hypothesis that LPA governs embryonic vascular formation by stimulating the migration of endothelial cells. In LPA1/LPA4 double morphant embryos and the LPA4 morphant embryos treated with Ki16425, not only is the extension of the SA abnormal, but also the connection between the ISV (SA) and the DA is disrupted (Fig. 8, F and H). This indicates that LPA signaling mediated by LPA1/LPA4 maintains the connection of endothelial cells, possibly by modulating cell-cell adhesion. Our next goal is to identify which of the processes affecting endothelial cells are regulated by LPA.

Supplementary Material

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (Grant Number: 09–11), the National Project on Protein Structural and Functional Analyses, from the Ministry of Education (Grant Number: MPB3), CREST (Japan Science and Technology Corporation), Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan (to J. A. (KAKENHI #22116004) and K. H. (#21770131)).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2, Figs. 1–5, and Movies 1–5.

- ATX

- autotaxin

- DA

- dorsal aorta

- DLAV

- dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessel

- hpf

- hours postfertilization

- ISV

- intersegmental vessel

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- LPC

- lysophosphatidylcholine

- LPE

- lysophosphatidylethanolamine

- LPS

- lysophosphatidylserine

- MO

- morpholino antisense oligonucleotide

- NPP

- nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase

- pNP-TMP

- p-nitrophenyl thymidine 5-monophosphate

- SA

- segmental artery

- zATX

- zebrafish autotaxin

- SPC

- sphingosylphosphorylcholine

- Tg

- transgenic

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- PCV

- posterior cardinal vein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stracke M. L., Krutzsch H. C., Unsworth E. J., Arestad A., Cioce V., Schiffmann E., Liotta L. A. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 2524–2529 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Umezu-Goto M., Kishi Y., Taira A., Hama K., Dohmae N., Takio K., Yamori T., Mills G. B., Inoue K., Aoki J., Arai H. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 158, 227–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tokumura A., Majima E., Kariya Y., Tominaga K., Kogure K., Yasuda K., Fukuzawa K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39436–39442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aoki J. (2004) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 477–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanaka M., Okudaira S., Kishi Y., Ohkawa R., Iseki S., Ota M., Noji S., Yatomi Y., Aoki J., Arai H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25822–25830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clair T., Aoki J., Koh E., Bandle R. W., Nam S. W., Ptaszynska M. M., Mills G. B., Schiffmann E., Liotta L. A., Stracke M. L. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 5446–5453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murata J., Lee H. Y., Clair T., Krutzsch H. C., Arestad A. A., Sobel M. E., Liotta L. A., Stracke M. L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 30479–30484 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin M. E., Herr D. R., Chun J. (2010) Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators 91, 130–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Contos J. J., Fukushima N., Weiner J. A., Kaushal D., Chun J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13384–13389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ye X., Hama K., Contos J. J., Anliker B., Inoue A., Skinner M. K., Suzuki H., Amano T., Kennedy G., Arai H., Aoki J., Chun J. (2005) Nature 435, 104–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Inoue M., Rashid M. H., Fujita R., Contos J. J., Chun J., Ueda H. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 712–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tager A. M., LaCamera P., Shea B. S., Campanella G. S., Selman M., Zhao Z., Polosukhin V., Wain J., Karimi-Shah B. A., Kim N. D., Hart W. K., Pardo A., Blackwell T. S., Xu Y., Chun J., Luster A. D. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Meeteren L. A., Ruurs P., Stortelers C., Bouwman P., van Rooijen M. A., Pradère J. P., Pettit T. R., Wakelam M. J., Saulnier-Blache J. S., Mummery C. L., Moolenaar W. H., Jonkers J. (2006) Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 5015–5022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koike S., Keino-Masu K., Ohto T., Sugiyama F., Takahashi S., Masu M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33561–33570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferry G., Giganti A., Cogé F., Bertaux F., Thiam K., Boutin J. A. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 3572–3578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Contos J. J., Ishii I., Fukushima N., Kingsbury M. A., Ye X., Kawamura S., Brown J. H., Chun J. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 6921–6929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sumida H., Noguchi K., Kihara Y., Abe M., Yanagida K., Hamano F., Sato S., Tamaki K., Morishita Y., Kano M. R., Iwata C., Miyazono K., Sakimura K., Shimizu T., Ishii S. (2010) Blood 116, 5060–5070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baldessari D., Mione M. (2008) Pharmacol. Ther. 118, 206–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Isogai S., Horiguchi M., Weinstein B. M. (2001) Dev. Biol. 230, 278–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakanaga K., Hama K., Aoki J. (2010) J. Biochem. 148, 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niwa H., Yamamura K., Miyazaki J. (1991) Gene 108, 193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Link V., Shevchenko A., Heisenberg C. P. (2006) BMC Dev. Biol. 6, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kishimoto T., Matsuoka T., Imamura S., Mizuno K. (2003) Clin. Chim. Acta 333, 59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nishimasu H., Okudaira S., Hama K., Mihara E., Dohmae N., Inoue A., Ishitani R., Takagi J., Aoki J., Nureki O. (2011) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsuda S., Okudaira S., Moriya-Ito K., Shimamoto C., Tanaka M., Aoki J., Arai H., Murakami-Murofushi K., Kobayashi T. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26081–26088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hama K., Aoki J., Fukaya M., Kishi Y., Sakai T., Suzuki R., Ohta H., Yamori T., Watanabe M., Chun J., Arai H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 17634–17639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B., Schilling T. F. (1995) Dev. Dyn. 203, 253–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee S. J., Chan T. H., Chen T. C., Liao B. K., Hwang P. P., Lee H. (2008) FASEB J. 22, 3706–3715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inoue A., Arima N., Ishiguro J., Prestwich G. D., Arai H., Aoki J. (2011) EMBO J. 30, 4248–4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thisse C., Thisse B. (2008) Nat. Protoc. 3, 59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ohta H., Sato K., Murata N., Damirin A., Malchinkhuu E., Kon J., Kimura T., Tobo M., Yamazaki Y., Watanabe T., Yagi M., Sato M., Suzuki R., Murooka H., Sakai T., Nishitoba T., Im D. S., Nochi H., Tamoto K., Tomura H., Okajima F. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 994–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yanagida K., Masago K., Nakanishi H., Kihara Y., Hamano F., Tajima Y., Taguchi R., Shimizu T., Ishii S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17731–17741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kimura T., Mogi C., Sato K., Tomura H., Ohta H., Im D. S., Kuwabara A., Kurose H., Murakami M., Okajima F. (2011) Cardiovasc. Res. 92, 149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Habeck H., Odenthal J., Walderich B., Maischein H., Schulte-Merker S. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1405–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Torres-Vázquez J., Gitler A. D., Fraser S. D., Berk J. D., Van N. P., Fishman M. C., Childs S., Epstein J. A., Weinstein B. M. (2004) Dev. Cell 7, 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilson B. D., Ii M., Park K. W., Suli A., Sorensen L. K., Larrieu-Lahargue F., Urness L. D., Suh W., Asai J., Kock G. A., Thorne T., Silver M., Thomas K. R., Chien C. B., Losordo D. W., Li D. Y. (2006) Science 313, 640–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu X., Le Noble F., Yuan L., Jiang Q., De Lafarge B., Sugiyama D., Bréant C., Claes F., De Smet F., Thomas J. L., Autiero M., Carmeliet P., Tessier-Lavigne M., Eichmann A. (2004) Nature 432, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ellertsdóttir E., Lenard A., Blum Y., Krudewig A., Herwig L., Affolter M., Belting H. G. (2010) Dev. Biol. 341, 56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ptaszynska M. M., Pendrak M. L., Stracke M. L., Roberts D. D. (2010) Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 309–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.