Abstract

Neurexins are presynaptic cell-adhesion molecules that form trans-synaptic complexes with postsynaptic neuroligins. When overexpressed in non-neuronal cells, neurexins induce formation of postsynaptic specializations in co-cultured neurons, suggesting that neurexins are synaptogenic. However, we now find that when overexpressed in neurons, neurexins do not increase synapse density, but instead selectively suppressed GABAergic synaptic transmission without decreasing GABAergic synapse numbers. This suppression was mediated by all subtypes of neurexins tested, in a cell-autonomous and neuroligin-independent manner. Strikingly, addition of recombinant neurexin to cultured neurons at sub-micromolar concentrations induced the same suppression of GABAergic synaptic transmission as neurexin overexpression. Moreover, experiments with native brain proteins and with purified recombinant proteins revealed that neurexins directly and stoichiometrically bind to GABAA-receptors, suggesting that they decrease GABAergic synaptic responses by interacting with GABAA-receptors. Our findings suggest that besides their other well-documented interactions, presynaptic neurexins directly act on postsynaptic GABAA-receptors, which may contribute to regulate the excitatory/inhibitory balance in brain.

INTRODUCTION

Neurexins are receptors for the presynaptic neurotoxin α-latrotoxin (Ushkaryov et al., 1992; Ushkaryov and Südhof, 1993), and are thought to function as presynaptic cell-adhesion molecules by binding to postsynaptic neuroligins and LRRTMs (Ichtchenko et al., 1995; Nguyen and Südhof, 1997; Irie et al., 1997; Scheiffele et al., 2000; Ko et al., 2009a; de Wit et al., 2009). In vertebrates, neurexins and neuroligins are synthesized throughout the brain in all excitatory and inhibitory neurons (Ullrich et al., 1995; Ichtchenko et al., 1995 and 1996). Neurexins and neuroligins are evolutionarily conserved, indicating that they perform a basic synaptic function (Tabuchi and Südhof, 2002; Li et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2007; Biswas et al., 2008). Moreover, neurexins belong to a larger protein family that includes neurexin-like proteins such as CASPR/CNTNAPs in vertebrates (Peles et al., 1997), neurexin-IV in Drosophila (Baumgartner et al., 1996), and Bam-2 in C. elegans (Colavita and Tessier-Lavigne, 2003). All of these molecules function as cell-adhesion and signaling proteins, and contain typical neurexin domains (LNS-domains with interspersed EGF-like domains), but are otherwise quite different (Missler et al., 1998). In addition to neuroligins and LRRTMs, neurexins bind to dystroglycan (Sugita et al., 2001) and to neurexophilins (Petrenko et al., 1996; Missler et al., 1998), but these interactions have not been studied in detail.

Vertebrate genomes contain three neurexin genes, each of which expresses larger α- and smaller β-neurexins from distinct promoters (Rowen et al., 2002; Tabuchi and Südhof, 2002). Furthermore, extensive alternative splicing of the primary transcripts of all α- and β-neurexins additionally diversifies neurexins, resulting in potentially thousands of evolutionarily conserved isoforms that are differentially expressed in brain (Ushkaryov et al., 1994; Ullrich et al., 1995; Patzke and Ernsberger, 2000; Zeng et al., 2006; Rissone et al., 2007; Rozic-Kotliroff and Zisapel, 2007). Although affinity of neurexins for neuroligins depends on their alternative splicing (Ichtchenko et al., 1995 and 1996; Boucard et al., 2005; Chih et al., 2006; Comoletti et al., 2006), the general significance of neurexin alternative splicing remains unknown.

Endogenous neurexins are largely presynaptic, as evidenced by their role as α-latrotoxin receptors (Ushkaryov et al., 1992; Sugita et al., 1999), their immunocytochemical localization in brain (Ushkaryov et al., 1992), and their accumulation and functional requirement in presynaptic nerve terminals in artificial synapses (Chubykin et al., 2005; Ko et al., 2009b). In mice, deletion of α-neurexins causes a presynaptic phenotype that includes a major decrease in action potential-evoked neurotransmitter release, and a massive impairment in Ca2+-channel function (Missler et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2005). In Drosophila, mutation of the single neurexin gene (which encodes an α-neurexin; Tabuchi and Südhof, 2002) also causes an ultrastructural and functional disorganization of neuromuscular junctions (Li et al., 2007). Consistent with a presynaptic localization and suggestive of a synaptogenic function, overexpressed neurexins in non-neuronal cells induce formation of postsynaptic specializations in co-cultured neurons (Graf et al., 2004; Nam and Chen, 2005). However, neurexins may also have postsynaptic effects since α-neurexin KO mice display a relative loss of postsynaptic NMDA-receptor activity (Kattenstroth et al., 2004), and neurexins may partly localize postsynaptically (Taniguchi et al., 2007).

Viewed together, the existing data thus suggest that neurexins function as presynaptic cell-adhesion molecules with essential functions in all organisms tested. However, no clear-cut view of the exact nature of these functions has emerged. Whereas the genetic data in mice and flies argue for a role in synapse assembly and function, but not in synaptogenesis (Missler et al., 2003; Li et al., 2007), the induction of postsynaptic specializations by transfected neurexins indicates a synaptogenic function (Graf et al., 2004; Nam and Chen, 2005). As the effects of neurexin overexpression in neurons has not been examined, it is unclear whether neurexins generally trigger formation of postsynaptic specializations. Moreover, a flurry of recent human genetics studies suggested that changes in the neurexin-1α gene are associated with autism (Szatmari et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2008; Marshall et al., 2008; Zahir et al., 2008) and/or schizophrenia (Kirov et al., 2008; Rujescu et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2008), while changes in the neurexin-3α gene are linked to addiction (Hishimoto et al., 2007; Lachman et al., 2007; reviewed in Südhof, 2008). Here, we show that neurexins unexpectedly interact with GABAA-receptors, and that overexpression of neurexins in neurons is not synaptogenic, but selectively inhibits GABAergic synaptic responses by a neuroligin-independent mechanism. These data suggest that neurexins may organize synapses not only via trans-synaptic interactions with postsynaptic cell-adhesion molecules, but also with neurotransmitter receptors.

RESULTS

Neurexin-2β downregulates GABAergic synaptic transmission

When neuroligins or neurexins are overexpressed in non-neuronal cells that are co-cultured with neurons, neuroligins induce formation of presynaptic specializations in the co-cultured neurons, while neurexins induce formation of postsynaptic specializations (Scheiffele et al., 2000; Graf et al., 2004; Chubykin et al., 2005; Nam and Chen, 2005). Moreover, overexpression of neuroligins in neurons increases synapse numbers (Chih et al., 2004; Boucard et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009). We therefore hypothesized that overexpression of neurexins in neurons should also increase synapse numbers.

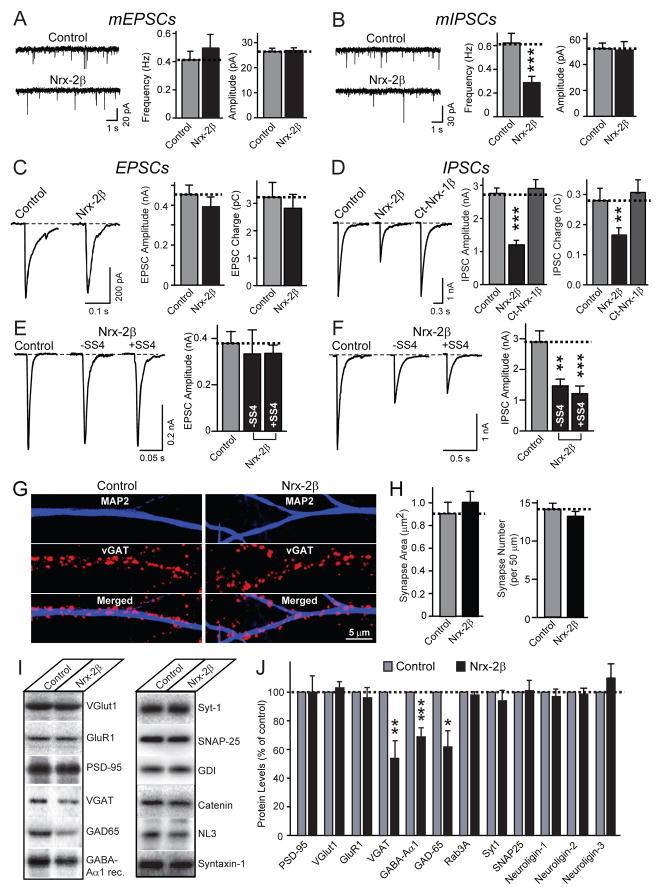

We infected cultured neurons with lentiviruses expressing EGFP alone or together with neurexin-2β, such that virtually all neurons are infected. We then measured in these neurons spontaneous miniature excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs and mIPSCs, respectively). Neurexin-2β caused no change in mEPSCs, but surprisingly induced a ~2-fold decrease in mIPSC frequency, without a significant change in mIPSC amplitude (Figs. 1A, 1B, S1A, and S1B). EGFP alone had no effect. We next recorded evoked synaptic responses (ESPCs and IPSCs), and detected a similar selective ~2-fold decrease in IPSC amplitude and charge, again without a significant change in EPSCs (Figs. 1C and 1D). This selective impairment in inhibitory GABAergic synaptic transmission by neurexin-2β was independent of alternative splicing at splice site 4 (Figs. 1E and 1F). Using immunocytochemistry, we found that neurexin-2β had no significant effect on the number or size of inhibitory synapses (Figs. 1G and 1H). Protein quantitations showed that neurexin-2β caused a small but significant decrease in the levels of pre- and postsynaptic proteins specific for GABAergic synapses, without changing their mRNA levels (Figs. 1I, 1J, and S1C). Thus, contrary to expectations, increasing neuronal neurexin-2β expression decreased the function of GABAergic but not glutamatergic synapses, without altering synapse numbers.

Figure 1. Lentivirally expressed neurexin-2β decreases GABAergic but not glutamatergic synaptic strength.

All data are from cultured hippocampal neurons infected with lentivirus expressing EGFP only (control), or co-expressing EGFP with neurexin-2β lacking an insert in splice site 4 (Nrx-2β), or other versions of neurexin-2β as specified.

A. and B. Representative traces (left) and summary graphs of the frequency (center) and amplitudes (right) of mEPSCs (A) or mIPSCs (B) recorded in 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 0.1 mM picrotoxin (A) or 10 μM CNQX (B) (mEPSCs: control: n=25 cells/3 cultures; Nrx-2β: n=26/3; mIPSCs: control: n=29/3; Nrx-2β: n=27/3).

C. and D. Representative traces (left) and summary graphs of the amplitude (center) and synaptic charge transfer (right, integrated over 0.2 s) of action potential-evoked EPSCs recorded in 0.1 mM picrotoxin (C) or IPSCs recorded in 10 μM CNQX (D; N-terminally truncated neurexin-1β [Ct-Nrx-1β] was included as additional negative control)(EPSCs: control: n=54/8; Nrx-2β: n=59/8; IPSCs: control: n=12/3; Nrx-2β: n=13/3; Ct-Nrx-1β: n=15/3).

E. and F. Representative traces (left) and summary graphs of the amplitudes (right) of EPSCs (E) and IPSCs (F) in neurons infected with control lentivirus, or lentivirus expressing neurexin-2β without (−SS4) and with an insert in splice site 4 (+SS4), recorded as described for C and D (EPSCs: control, n=11/2; Nrx-2β +SS4, n=11/2; Nrx-2β −SS4, n=11/2. IPSCs: control, n=50/8; Nrx-2β +SS4, n=51/8; Nrx-2β −SS4, n=46/8).

G. Representative images of neurons infected with control and neurexin-2β expressing lentiviruses stained for MAP2 and the vesicular GABA transporter vGAT.

H. Quantitation of synapse area (left) and density (right) in the experiments described in G (control: n=29/3; Nrx-2β: n=40/3).

I. and J. Representative immunoblots (F) and summary graphs of protein levels (G) measured in lysates of cultured hippocampal neurons infected with control or Nrx-2β expressing lentivirus. Protein levels were measured by quantitative immunoblotting with 125I-labled secondary antibodies and phosphoImager detection (n=3–5 cultures).

For all representative traces and images, scale bars apply to all panels in a set. All summary graphs show means ± SEMs; statistical comparisons were made by Student’s t-test (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001). For additional data, see Fig. S1.

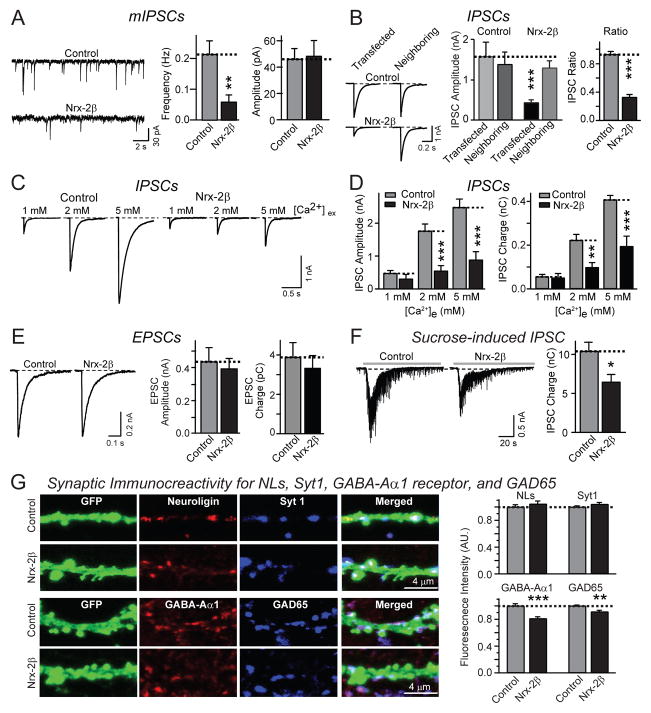

Neurexins decrease GABAergic responses in transfected neurons

We next transfected neurons with neurexin-2β or a control plasmid, such that only a small percentage of neurons express neurexin-2β, and recorded from the transfected neurons that were identified via co-transfected CFP. Similar to lentiviral delivery of neurexin-2β, transfection of neurexin-2β caused a selective >2-fold decrease in mIPSC frequency (Figs. 2A and S2A) and in evoked IPSC amplitude, without altering EPSCs (Figs. 2B-2E). To ensure specificity of the observed effect, we measured IPSCs in neighboring transfected and non-transfected neurons on the same coverslip (Fig. 2B). Only transfected neurons expressing neurexin-2β exhibited depressed GABAergic synaptic responses. The neurexin-2β induced decrease in IPSCs was not alleviated when neurotransmitter release was increased by elevating the extracellular Ca2+-concentration (Figs. 2C and 2D). Moreover, IPSCs induced by hypertonic sucrose (which induces exocytosis of all readily-releasable vesicles) were also significantly decreased by transfected neurexin-2β (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2. Postsynaptic expression of neurexin-2β impairs inhibitory synaptic strength.

All data are from cultured hippocampal neurons co-transfected with an EGFP expression plasmid and either an empty vector (control), or a vector encoding neurexin-2β (Nrx-2β). A. Representative traces (left), and summary graphs of the mean frequency (center) and amplitudes (right) of mIPSCs recorded in 1 μM TTX and 10 μM CNQX (control: n=26/3; Nrx-2β: n=24/3).

B. Representative traces (left), mean amplitudes (center), and IPSC ration (right) of IPSCs recorded from neighboring transfected and non-transfected neurons (control: n=11 pairs/3 cultures; Nrx-2β: n=12 pairs/3 cultures).

C. and D. Representative traces (C) and summary graphs of the amplitudes (D left) and synaptic charge transfer (D right) of IPSCs recorded in 1, 2 and 5 mM extracellular Ca2+ (control: n=17/3, 17/3 and 20/3 at 1, 2 and 5 mM extracellular Ca2+; Nrx-2β: n=17/3, 18/3 and 23/3 at 1, 2 and 5 mM Ca2+).

E. Representative traces (left), mean amplitudes (center), and mean charge transfer (right) of EPSCs recorded from control or neurexin-2β transfected neurons in the presence of 10 μM picrotoxin (control: n=28/4; Nrx-2β: n=32/4).

F. Representative traces (left) and mean charge transfer (right; integrated over 60 s) of IPSCs elicited by hypertonic sucrose (0.5 M for 30 s; control: n=36/8; Nrx-2β: n=42/8).

G. Measurement of synaptic signals for neuroligins and GABA-Aα1 receptors in neurons expressing neurexin-2β. Transfected neurons were stained with a pan-neuroligin antibody (Song et al., 1998) and synaptotagmin-1 (Syt1), or for GABA-Aα1 receptors and GAD65. Panels show representative images (left) and quantitations of the staining intensity per synapse for all four markers (right).

For all representative data, scale bars apply to all panels in a set. All summary graphs show means ± SEMs; statistical comparisons by Student’s t-test yielded: n.s.=non-significant, *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001. For additional data, see Fig. S2.

Similar to pan-neuronal lentiviral expression of neurexin-2β, transfection of neurexin-2β did not significantly change the density of excitatory or inhibitory synapses (Figs. S2B-S2E). Immunocytochemically, no change in the postsynaptic neuroligin signal was observed, whereas we detected a small but significant decrease in the synaptic signal for GABA-Aα1 receptors and GAD65 (Fig. 2G), consistent with the decrease in GABAergic synaptic protein levels after lentiviral expression of neurexin-2β (Figs. 1I and 1J).

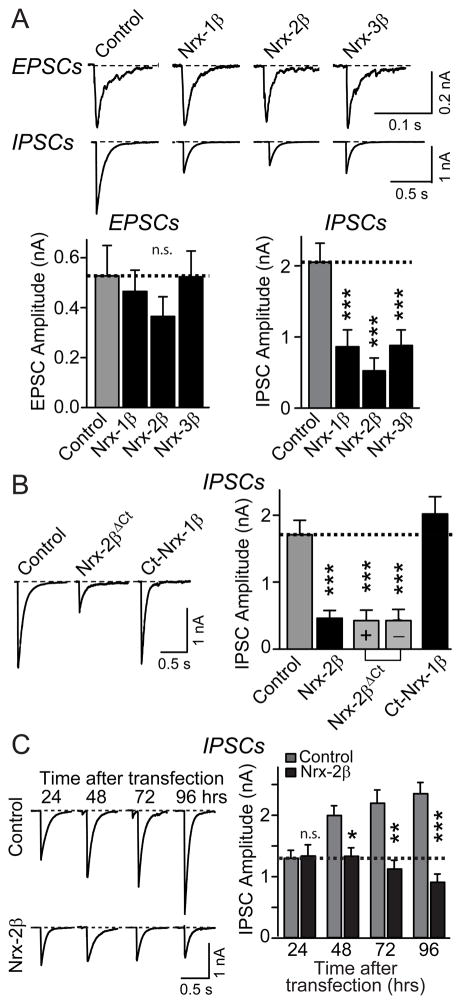

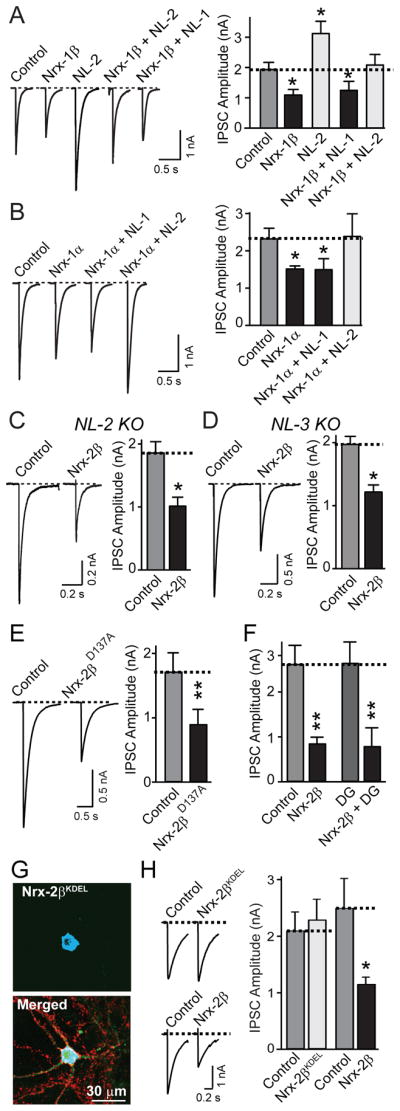

To test whether all neurexins decrease GABAergic synaptic transmission, we tested neurexin-1β, -1α, -2β, and -3β. All neurexins similarly impaired IPSCs (Fig. 3A; for neurexin-1α, see Fig. 4B). Transfection of C-terminally truncated neurexin-2βΔct lacking the cytoplasmic neurexin tail also decreased IPSCs, whereas deletion of the extracellular sequences of neurexin-1β abolished suppression of IPSCs, suggesting that postsynaptically expressed neurexin acts by an extracellular interaction (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Extracellular sequences of neurexins mediate decrease of IPSCs.

Different neurexins were examined in transfected cultured hippocampal neurons as described for Fig. 2.

A. Representative traces (top) and mean amplitudes (bottom) of EPSCs and IPSCs recorded from neurons transfected with control vector or vectors encoding neurexin-1β (Nrx-1β), -2β (Nrx-2β), or -3β (Nrx-3β; EPSCs: control, n=30/4; Nrx-1β, n=31/4; Nrx-2β, n=28/4; Nrx-3β, n=29/4. IPSCs: control, n=42/4; Nrx-1β, n=23/3; Nrx-2β, n=48/4; Nrx-3β, n=21/3).

B. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes of IPSCs (right) recorded from neurons transfected with control vector or vectors expressing wild-type neurexin-2β (Nrx-2β), C-terminally truncated neurexin-2β (Nrx-2βΔCt) composed of its extracellular sequences and transmembrane region with (+) and without (-) an insert in splice site 4, or N-terminally truncated neurexin-1β (Ct-Nrx-1β) composed of only its transmembrane region and cytoplasmic tail (control: n=32/5; Nrx-2β: n=52/5; Nrx-2βΔCt without SS4: n=32/5; Nrx-2βΔCt with SS4: n=24/4; Ct-Nrx-1β: n=42/3).

C. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes (right) of IPSCs recorded from neurons transfected with control or neurexin-2β expressing vectors on DIV10, and analyzed at the indicated times after transfection (for all times tested: control, n= 5/3, Nrx-2β, n=15/3).

For all representative traces, scale bars apply to all traces in a set. All summary graphs show means ± SEMs; statistical comparisons by Student’s t-test yielded: n.s.=non-significant, *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001. For additional data, see Fig. S3.

Figure 4. Neurexins impair IPSCs independent of neuroligins.

Hippocampal neurons transfected with the indicated combinations of expression vectors were analyzed as described for Fig. 2.

A. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes (right) of IPSCs recorded from neurons transfected with control vector, or vectors expressing only neurexin-1β (Nrx-1β), only neuroligin-2 (NL2), neurexin-1β together with neuroligin-2 (Nrx-1β + NL2), or neurexin-1β with neuroligin-1 (Nrx-1β + NL1; control: n=42/5; Nrx-1β: n=55/5; Nrx-1β + NL-1: n=26/4; Nrx-1β + NL-2: n=25/4; NL-2: n=9/1).

B. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes (right) of IPSCs recorded from neurons transfected with control vector, or vectors expressing only neurexin-1α (Nrx-1α), or together with neuroligin-2 (Nrx-1α + NL2), or only neuroligin-1 (Nrx-1α + NL1; control: n=48/5; Nrx-1α: n=38/5; Nrx-1α + NL-1: n=19/3; Nrx-1α + NL-2: n=16/3).

C and D. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes (right) of IPSCs recorded from neurons cultured from neuroligin-2 KO (C) or neuroligin-3 KO mice (D), and transfected with control vector or neurexin-2β (Nrx-2β; C, control: n=20/3; Nrx-2β: n=19/3; D, n = 9 pairs of neighboring non-transfected and transfected neurons/3 cultures).

E. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes (right) of IPSCs recorded from neighboring non-transfected and transfected neurons expressing mutant neurexin-2β (Nrx-2βD137A) in which a point mutation abolishes Ca2+- and neuroligin-binding to the neurexin-2β LNS-domain (control: n= 15 pairs/3 cultures).

F. Mean amplitudes of IPSCs recorded from neurons transfected with control vector, or vectors expressing neurexin-2β alone (Nrx-2β), neurexin-2β together with dystroglycan (Nrx-2β + DG), or dystroglycan alone (DG; control: n=16/3; Nrx-2β: n=11/3; Nrx-2β + DG: n=16/3; DG: n=12/2).

G. and H. Truncated neurexin-2β with a C-terminal KDEL sequence is retained in the ER (G) and unable to decrease IPSCs (H). G depicts representative images of neurons demonstrating that neurexin-2βKDEL is retained in the ER (Nrx-2βKDEL; visualized via a myc-epitope; top); colabeling for synapsin in the merged image reveals that the neuron nevertheless forms abundant synapses (Merged; bottom). H (left, representative traces; right, summary graphs) show that an ER-retained neurexin-2β mutant that still binds neuroligin (Fig. S4) has no effect on IPSC amplitudes (Nrx-2βKDEL transfection; control: n=14/3; Nrx-2βKDEL: n=13/3; Nrx-2β transfection; control: n=8/3; Nrx-2β: n=8/3).

For all representative traces, scale bars apply to all traces in a set. Summary graphs show means ± SEMs; statistical comparisons by Student’s t-test yielded: *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01. For additional data, including postsynaptic knockdowns of neurexins, see Fig. S4.

Does overexpressed neurexin block the maturation of new synapses, or impair the function of existing synapses? To examine this question, we monitored the time course of neurexin-induced suppression of IPSCs. We transfected neurons with neurexin-2β or control vector at 10 days in vitro (DIV10), and measured the IPSC amplitudes 24–96 h after transfection. Control-transfected neurons exhibited a continuous increase in IPSC amplitudes after DIV10, consistent with progressive maturation of synapses. In contrast, neurexin-2β expressing neurons displayed no further increase in IPSC amplitudes after DIV10 (Fig. 3C). Thus, neurexin-2β did not impair existing GABAergic synapses, but prevents the normal developmental increase in inhibitory synaptic strength. This observation cannot be explained by an indirect effect of neurexins on synaptic activity, because chronic increases or decreases in synaptic activity (by incubating neuronal cultures with picrotoxin or with CNQX, APV, TTX, or a combination thereof, respectively) caused no change in the suppression of IPSCs by neurexin-2β (Fig. S3).

Neurexins act on GABAergic responses independent of neuroligins

Neuroligin-2 is localized to inhibitory synapses, is essential for normal inhibitory synaptic strength in brain, and binds to all neurexins (Graf et al., 2004; Varoqueaux et al., 2004; Comoletti et al., 2006; Chubykin et al., 2007). Thus, neurexins may impair IPSCs by a selective sequestration of neuroligin-2.

To test this hypothesis, we co-expressed neurexin-1β or -1α with neuroligin-1 or -2 in neurons, with the notion that since both neuroligins bind to neurexins, they would both similarly counteract the sequestration of endogenous neuroligin-2 by overexpressed neurexins. However, co-expression of neuroligin-1 had no effect on the suppression of IPSCs by neurexins. Neuroligin-2 alone enhanced IPSCs as described (Chubykin et al., 2007); co-expression of neuroligin-2 with neurexins canceled out the effects of each separate protein (Figs. 4A and 4B). Moreover, we found that overexpression of neurexin-2β produced the same suppression of GABAergic responses in neurons from neuroligin-2 and -3 KO mice (Figs. 4C and 4D). Note that different from acute slices (Chubikyn et al., 2007), neuroligin-2 KO neurons did not exhibit a decrease in IPSC amplitude in culture (Fig. S4A). Finally, we found that a neurexin mutant (neurexin-2βD137A) which does not bind to neuroligins (Reissner et al., 2008; see also Fig. 7 below) still effectively decreased IPSCs (Fig. 4E). Finally, to examine whether neurexin binding to dystroglycan (Sugita et al., 2001) may decrease IPSCs, we examined the effect of dystroglycan transfection on IPSCs, either alone or in combination of neurexins. Dystroglycan had no effect either on IPSCs when transfected alone, or on the neurexin-induced suppression of IPSCs (Fig. 4F).

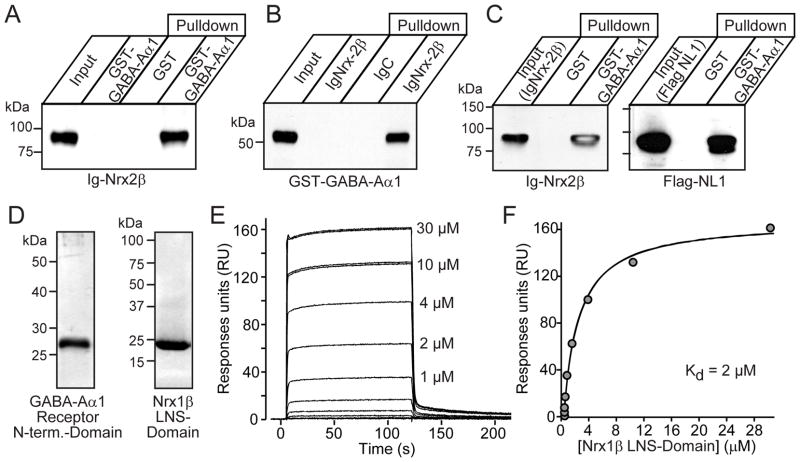

Figure 7. Neurexins directly bind to GABAAα1-receptors.

All data shown analyze binding of purified recombinant proteins.

A and B. Binding of purified GST or a GST-fusion protein of the N-terminal domain of rat GABAAα1-receptor to Ig-control (IgC) or Ig-neurexin-2β fusion proteins (IgNrx-2β), analyzed either by immobilizing the GST-fusion proteins and measuring binding of IgNrx-2β (A), or immobilizing the Ig-fusion proteins and measuring binding of GST-GABAAα1 (B). Binding was visualized by immunoblotting as indicated.

C. Binding of recombinant flag-tagged neuroligin-1 (NL1) to immobilized GST-GABAAα1 receptors by forming a tripartite complex with neurexin-2β. Immobilized GST or the GST-GABAAα1 fusion protein were incubated with both neurexin-2β and neuroligin-1, and bound proteins were analyzed by immunopblotting for neurexin-2β (left) or neuroligin-1 (right).

D. SDS-gels of purified proteins used for binding affinity measurements (left: silver-stained gel of the purifed recombinant GABAAα1-receptor N-terminal domain; right: Coomassie-stained gel of the purified neurexin-1β LNS-domain).

E. Surface-plasmon resonance sensorgrams showing the binding of neurexin-1β to the extracellular N-terminal domain of the GABAAα1-receptor. Each line corresponds to the indicated concentration of neurexin-1 β injected onto the immobilized GABAAα1-receptor surface. The sensorgrams demonstrate a concentration-dependent association as expected for a bimolecular association.

F. Surface-plasmon resonance quantitation of the binding of neurexin-1β to the N-terminal domain of the GABAAα1-receptor. The maximum steady-state binding of neurexin-1β to the GABAAα1-receptor is plotted as a function of the neurexin-1β concentration. Dissociation constants were calculated by tting the curve to a single-site binding model. Each data point was measured twice, and both measurements are shown on the gure, but overlap with each other. The experiment was repeated with higher GABAAα1-receptor immobilization on the chip surface, and similar affinities were obtained (not shown). For additional data, see Fig. S7.

Together, these data show that increasing neurexin expression do not impair inihibitory synaptic transmission by sequestering endogenous neuroligins. Given the primarily presynaptic localization of neurexins, the question arises whether transfected neurexins decrease inhibitory synaptic strength by a true postsynaptic action, or act in the postsynaptic neuron only after reaching synapses at the cell surface, and thus act by a quasi presynaptic mechanism. Pan-neuronal loss-of-function experiments of neurexins cannot be used to address this question because loss of α-neurexins alone already severely impairs neurotransmitter release, preempting any analysis of a postsynaptic effect (Missler et al., 2003). Thus, we addressed this question by testing whether a selective postsynaptic shRNA-dependent knockdown of all neurexins causes a phenotype opposite to the neurexin overexpression (Figs. S4B-S4F), which would indicate a normally postsynaptic function of neurexins in this regard, and whether expression of a neurexin mutant that is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) still suppresses inhibitory synaptic transmission (Figs. 4G–4H and S4C–S4I).

We developed shRNAs that efficiently knock down expression of all α- and β-neurexins (Fig. S4B). Expression of these shRNAs in transfected neurons, however, did not cause a change in inhibitory synaptic transmission, either in spontaneous or evoked synaptic responses (Figs. S4C–S4F). Next, we expressed a soluble truncated neurexin-2β mutant that contains a C-terminal KDEL sequence (Nrx-2βKDEL). Nrx-2βKDEL still binds to neuroligins, but is retained in the ER, and had no effect on inhibitory synaptic transmission (Figs. 4G–4H and S4G–S4I). Thus, neurexins have to be exported through the secretory pathway in order to act on GABAergic synapses, and transfected neurexins likely do not act in the postsynaptic neuron proper, but at synapses on the surface of the transfected neuron in a manner simulating a presynaptic action.

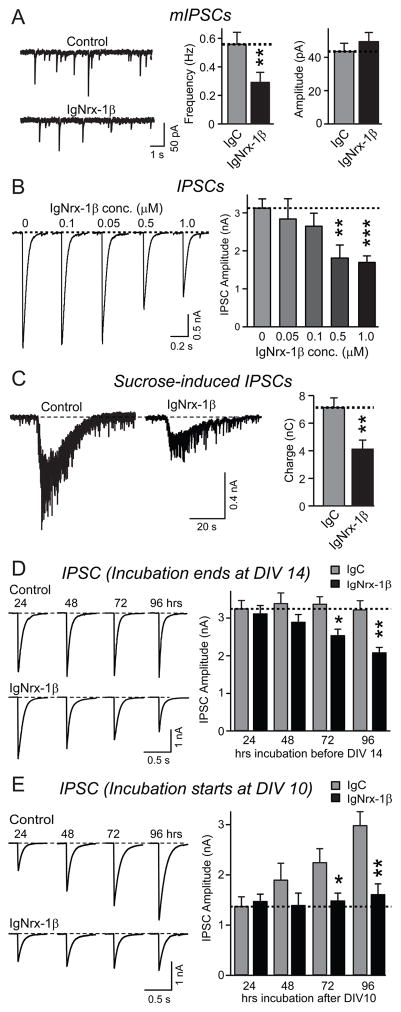

Recombinant neurexin-1β added to the medium suppresses GABAergic responses

If neurexins act on inhibitory synapses via an extracellular effect, recombinant neurexins added to the medium should simulate this action. To test this hypothesis, we incubated cultured neurons from DIV10 to DIV14 with a recombinant neurexin protein composed of the extracellular domains of neurexin-1β fused to the Fc domain of human immunoglobulin (IgNrx-1β), using recombinant protein containing only the human immunoglobulin domain (IgC) as a control. IgNrx-1β specifically decreased the mIPSC frequency but not the mIPSC amplitude (Fig. 5A), and suppressed evoked IPSCs but not evoked EPSCs; IgNrx-1β concentrations as low as 0.5 μM were effective (Figs. 5B, S5A and S5B). Similar to transfected neurexins, IgNrx-1β caused a significant decrease in the readily-releasable pool at GABAergic synapses (Fig. 5C), but produced no detectable alteration in release probability as monitored with the paired-pulse ratio (Fig. S5C). Moreover, protein measurements revealed that IgNrx-1β only produced a small change in proteins specific for GABAergic synapses without other major changes (Fig. S5D). Thus, simple addition of extracellular neurexin-1β protein selectively suppresses GABAergic synapse function.

Figure 5. Recombinant neurexin-1β in medium inhibits IPSCs.

All data are from cultured hippocampal neurons incubated with purified control Ig-fusion protein (IgC) or neurexin-1β Ig-fusion protein containing the extracellular domains of neurexin-1β (IgNrx-1β). Except where noted, neurons were treated for 96 h at 37 °C with 1 μM protein.

A. Representative traces (left) and summary graphs of the frequency (center) and amplitudes (right) of mIPSCs monitored in 1 μM TTX and 10 μM CNQX (IgC: n=19/3; IgNrx-1β: n=19/3).

B. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes (right) of evoked IPSCs recorded from neurons incubated with the indicated concentrations of IgNrx-1β (control: n=17/3; 1 μM: n=12/3; 500 nM: n=13/3; 100 nM: n=7/3; 50 nM: n=7/3).

C. Representative traces (left) and mean charge transfer (right) of IPSCs elicited by hypertonic sucrose (0.5 M for 30 s; IgC: n=14/3; IgNrx-1β: n=15/3).

D. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes (right) of evoked IPSCs recorded from neurons treated with IgC or IgNrx-1β for the indicated times, with all incubations ending at DIV14 (24 h: control, n=19/3, IgNrx-1β: n=14/3; 48 h: control, n=14/3, IgNrx-1β: n=15/3; 72 h: control, n=19/3, IgNrx-1β: n=19/3; 96 h: control, n=14/3, IgNrx-1β: n=15/3).

E. Representative traces (left) and mean amplitudes (right) of evoked IPSCs recorded from neurons treated with IgC or IgNrx-1β for the indicated times after the incubations were started at DIV10 (24 h: control, n=24/4, IgNrx-1β: n=26/4; 48 h: control, n=18/3, IgNrx-1β: n=18/3; 72 h: control, n=18/3, IgNrx-1β: n=22/3; 96 h: control, n=18/3, IgNrx-1β: n=18/3). For all representative traces, scale bars apply to all traces in a set. All summary graphs show means ± SEMs; statistical comparisons by Student’s t-test yielded: n.s.=non-significant, *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001. For additional data, see Fig. S5.

We next studied the time course of IgNrx-1β action on IPSCs. We either added 1 μM IgNrx-1β at defined times between DIV10 and DIV14, and measured IPSCs at DIV14 (Fig. 5D), or we added IgNrx-1β at DIV10, and measured IPSCs 24–96 h afterwards (Fig. 5E). In both types of experiments, addition of neurexin-1β prevented the normal developmental increase in IPSC size, without a significant effect on IPSCs already present at the time at which IgNrx-1β was added. These results, which agree with those obtained with transfected neurons (Fig. 3C), indicate that neurexins do not inhibit existing GABAergic synapses in neurons, but prevent increases of GABAergic synaptic strength during the culture period.

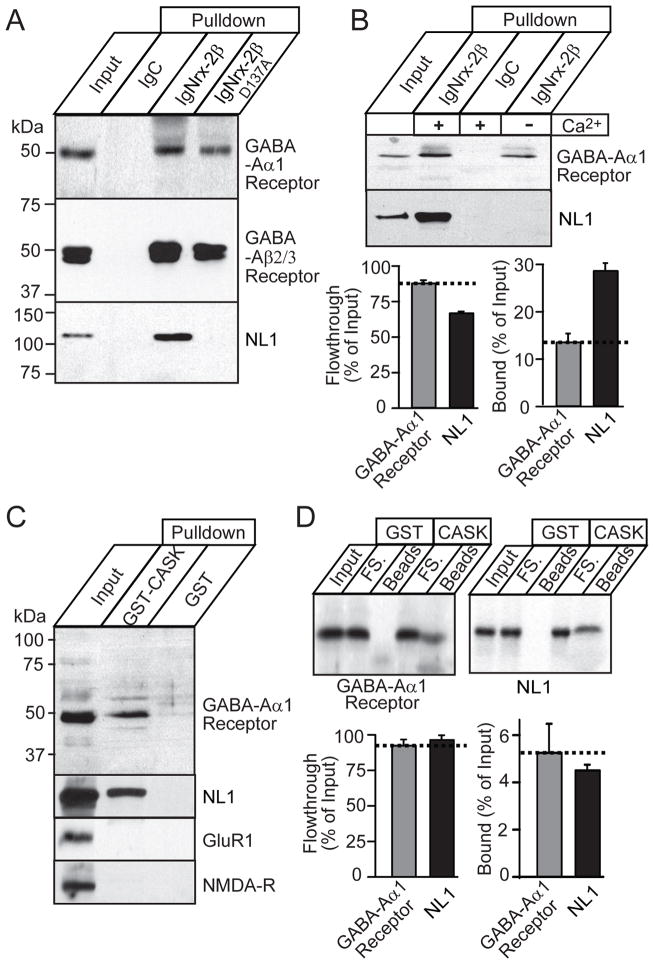

Neurexins interact with GABAAα1-receptors

Do neurexins interact with components of GABAergic synapses? To explore this possibility, we immobilized Ig-neurexin and Ig-control proteins, and performed affinity chromatography experiments with brain proteins solubilized in Triton X-100. Immunoblotting of bound proteins with a series of antibodies revealed specific binding of neuroligin-1 (as expected) and of GABAA-receptors (both the α1 and β2/3 subunits), but not of AMPA- or of NMDA-type glutamate receptors (Figs. 6A, 6B, and S6A-S6C). Measurements of bound proteins relative to the flow-through showed that the GABAAα1-receptor was retained quantitatively, with approximately half the efficiency of neuroligin-1 (Fig. 6B). In contrast to neuroligins, binding of GABAAα1-receptor to neurexin was Ca2+-independent (Fig. 6B), and a mutation in the neurexin Ca2+-binding sequence that blocks neuroligin-1 binding had no effect on GABAAα1-receptor binding (Fig. 6A). These observations were fully confirmed using recombinant proteins expressed in transfected HEK293 cells (Figs. S6D-S6G), suggesting that neurexins directly bind to GABAAα1-receptors in a Ca2+-independent manner.

Figure 6. Neurexins form a complex with GABAA-receptors.

All data shown are from affinity chromatography experiments using immobilized Ig- or GST-fusion proteins and Triton X-100 solubilized rat brain proteins.

A. Affinity purification of GABAA-receptors on neurexin-2β. Immobilized IgC or Ig-fusion proteins of the extracellular sequences of wild-type neurexin-2β (IgNrx-2β) or of neurexin-2β with a Ca2+-binding site point mutation that blocks neuroligin-binding (IgNrx-2βD137A) were used as affinity matrices for rat brain proteins solubilized in Triton X-100. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting for GABAAα1- and GABAAβ2/3-receptors and neuroligin-1.

B. Quantitative, Ca2+-independent binding of GABAAα1-receptor to IgNrx-2β. Solubilized rat brain proteins were bound to IgNrx-2β or IgC in the presence of 2.5 mM Ca2+, or of 0 mM Ca2+ plus 5 mM EDTA. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting for GABAAα1-receptor and neuroligin-1 (NL1) with ECL detection (top), and additionally quantified for the Ca2+-containing experiments with 125I-labeled secondary antibodies and phosphoImager detection (bottom; means ± SEMs, n=8).

C. Affinity chromatography of brain proteins on immobilized GST-CASK containing the CASK PDZ-domain (GST-CASK), or on GST alone. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting for GABAAα1-receptor, neuroligin-1 (NL1), GluR1, and NMDA-receptor (NMDA-R).

D. Quantitation of the binding of endogenous brain GABAAα1-receptor and neuroligin-1 (NL1) to immobilized GST-CASK or GST. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with 125I-labeled secondary antibodies and phosphoimager detection; top panels show a representative blot, and bottom panels summary graphs (means ± SEMs; n=6).

For additional raw data and controls, see Fig. S6.

Are endogenous GABAAα1-receptor/neurexin complexes present in brain? We examined this question by affinity-purifying neurexins from brain homogenates with an immobilized GST-fusion protein containing the CASK PDZ-domain that avidly binds to the C-terminal cytoplasmic sequence of neurexins (Hata et al., 1996). GST-CASK captured both GABAAα1-receptor and neuroligin-1 (Figs. 6C and 6D). Quantitations of bound proteins suggested that similar amounts of the GABAAα1-receptor and neuroligin-1 were bound by the CASK PDZ-domain (Fig. 6D). This binding was not due to a direct interaction of the GABAAα1-receptor with GST-CASK because GST-CASK could only affinity-purify the GABAAα1-receptor from transfected HEK293 cells when neurexin-1β was co-expressed with the receptor (Fig. S6H), demonstrating that GST-CASK pulls down a neurexin/GABAAα1-receptor complex.

Direct extracellular interaction of neurexins and GABAAα1-receptors

The robust effects of neurexin on GABAergic synaptic transmission (Figs. 1–5) could only be accounted for by their interaction if their extracellular domains bound to each other. Thus, we produced a recombinant GST-fusion protein of the extracellular domain of GABAAα1-receptors, and tested its binding to purified Ig-neurexin. We observed specific binding when either neurexin or the GABAAα1-receptor was pulled down (Figs. 7A and 7B). We next tested whether the GABAAα1-receptor and neuroligin-1 could bind to neurexins simultaneously. Using recombinant proteins, we found that indeed, immobilized GABAAα1-receptor not only captured neurexin-2β, but also neuroligin-1, demonstrating a tripartite interaction (Fig. 7C). Finally, we examined the affinity of the neurexin-GABAAα1 receptor interaction, using purified recombinant proteins that were not fused to GST or IG (Fig. 7D). Using surface plasmon resonance measurements, we found a tight, specific, and saturable interaction between these two proteins with a micromolar affinity, confirming a direct binding reaction (Figs. 7E and 7F).

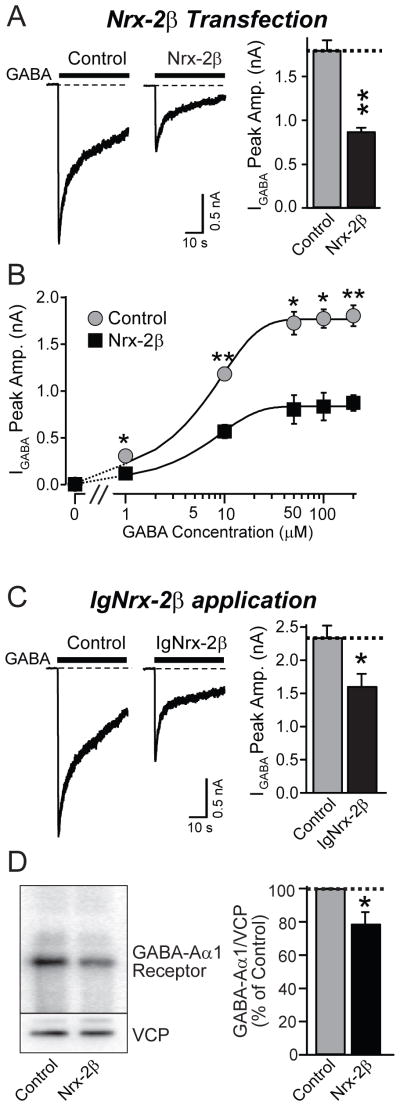

Neurexins inhibit GABAAα1-receptor currents in transfected HEK293 cells

Does the interaction of neurexins with GABAA-receptors directly decrease GABAergic currents? To test this question, we transfected neurexin-2β into non-neuronal HEK293 cells that stably express GABAA-receptors on their surface (Wong et al., 1994). Neurexin-2β robustly inhibited GABA-induced currents in the HEK293 cells (Fig. 8A). Titration of the GABA-induced currents with different GABA concentrations revealed no change in the kinetics of dose-response curve, but a general suppression of the response (Fig. 8B and Suppl. Fig. 8). Moreover, incubation of HEK293 cells expressing GABAA-receptors for 48 h with purified neurexin protein (IgNrx-2β; 1 μM) also suppressed GABA currents (Fig. 8C), and decreased the levels of cellular GABAA-receptor protein (Fig. 8D). Thus, neurexins appear to act directly on GABAA-receptors.

Figure 8. Neurexin-2β impairs GABAAα1-receptor function in transfected HEK293 cells.

A. Representative traces (left) and peak amplitudes (right) of currents induced by application of 0.2 mM GABA to HEK293 cells stably expressing GABAA-receptors (α1β2γ2, CRL-2029 from ATCC), and transfected with pCMV5 (control) or vector expressing neurexin-2β (control: n=18/3; Nrx-2β: n=18/3).

B. Plot of the current amplitude induced as described in A. as a function of the GABA concentration (control: n=19/4; Nrx-2β: n=17/4). For a scaled plot to document a lack of change in apparent GABA-affinity, see Suppl. Fig. 12.

C. Representative traces (left) and peak amplitudes (right) of currents induced by application of 0.2 mM GABA to HEK293 cells stably expressing GABAA receptors that had been incubated for 48 h with 1 μM control IgC or IgNrx-2β (control: n=15/3; IgNrx-2β: n=16/3).

D. Quantitation of the levels of GABAAα1-receptor in HEK293 cells that stably express GABAA-receptors, and were transfected with either an empty vector (control), or a vector encoding neurexin-2β (Nrx-2β) (n= 13 independent cultures).

For all representative traces, scale bars apply to all traces in a set. All summary graphs show means ± SEMs; statistical comparisons by Student’s t-test yielded *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001. For additional data, see Fig. S8.

DISCUSSION

Here we show that neurexins directly bind to the extracellular domains of GABAA-receptors, and specifically inhibit postsynaptic GABAA-receptors by a neuroligin-independent mechanism. We made six principal observations

First, neurexins directly interact with GABAAα1-receptors, as shown by binding of recombinant IgNrx-2β to endogenous GABAAα1-receptors in brain and to transfected GABAAα1-receptors in HEK293 cells; co-immunoprecipitation of neurexin-1β with GABAAα1-receptors from transfected HEK293 cells; pulldown of endogenous brain neurexin/GABAAα1-receptor complexes and of recombinant neurexin/GABAAα1-receptor complexes with the CASK PDZ-domain; and measurements of the direct interaction of the purified extracellular domains of neurexin and GABAA α1-receptors (Figs. 6, 7, S6 and S7).

Second, increasing neurexin expression decreases GABAergic but not glutamatergic synaptic transmission. This conclusion is based on lentiviral overexpression of neurexins (Fig. 1), transfection of neurexins (Figs. 2 and 3), and addition of recombinant neurexin to the medium (Fig. 5). Neurexins have a large effect (>2-fold decrease in IPSCs in most assays) that is specific (no changes in EPSCs, no decreases in synapse numbers or major changes in neuronal protein composition; Figs. 1–5 and S1–S5). Possibly most unexpected is the potency of recombinant neurexin that specifically suppressed IPSCs at only 0.5 μM (Fig. 5). All neurexins tested had a similar effect that was independent of alternative splicing at site #4 (Figs. 1–4).

Third, neurexins act via an extracellular mechanism on the neuronal surface. This was shown by the effectiveness of recombinant neurexin added to the culture medium (Fig. 5), and of over-expressed neurexin-2βΔCt which lacks a cytoplasmic tail (Fig. 3). In contrast, Ct-neurexin-1β composed of only the common neurexin cytoplasmic tail and transmembrane region was inactive (Fig. 2), as was mutant neurexin that is retained intracellularly (Fig. 3). Moreover, a neurexin-2β mutant that is retained in the ER is inactive, and postsynaptic knockdown of neurexins has no effect (Figs. 4 and S4).

Fourth, neurexins inhibit GABAergic responses independent of neuroligins. Co-transfection of neurexins with neuroligin-1 or neuroligin-2 did not ablate the inhibitory effect of neurexins on GABAergic synaptic transmission (Figs. 4A and 4B); neurexin-2β still inhibited GABAergic transmission in KO neurons lacking neuroligin-2, the only neuroligin specifically involved in inhibitory synaptic transmission (Chubykin et al., 2007), or neuroligin-3 (Figs. 4C and 4D); recombinant neurexin added to cultured neurons had the same effect as transfected neurexins (Fig. 5), which would not be expected if the overexpressed neurexins sequestered neuroligins in the neurons; a neurexin mutant that does not bind to neuroligins still bound to GABAA-receptors, and still inhibited GABAergic synaptic transmission (Figs. 4E and 6A); and a neurexin-2β mutant that is retained in the ER of neurons where it still binds to neuroligins did not decrease inhibitory synaptic strength (Fig. 4). Note that the experiments with the various splice variants of neurexins and their mutants also rule out a participation of the recently discovered interaction of neurexins with LRRTMs (Ko et al., 2009; de Wit et al., 2009).

Fifth, neurexins likely act by binding directly to GABAAα1-receptors on the cell surface. This conclusion is inherent to the findings we made in neurons after addition of recombinant neurexin to the medium (Fig. 5) and after transfection of various neurexin mutants (Figs. 2–4), and further amplified by the finding that transfection of neurexin-2β into GABAA-receptor expressing HEK293 cells or addition of IgNrx-2β to such cells suppressed GABA-induced currents in these non-neuronal cells (Fig. 8).

Sixth, finally, an excess of neurexins does not impair the functions of existing GABAergic sites – receptors and/or synapses – but prevents the developmental increase of GABAergic synaptic transmission in cultured neurons. Both for neurexin-transfected neurons and for untransfected neurons treated with recombinant neurexin, the neurexin “froze” the neuron in the state it was at the point at which the treatment was started (Figs. 3 and 5).

Relation to previous studies

Our study appears to contradict nearly all previously published reports on neurexins, including many from our own laboratory. As described below, however, some of these contradictions may be more apparent than real.

We observed that excess neurexins selectively decrease inhibitory synapses, instead of promoting formation of excitatory synapses as suggested in studies using co-cultures of neurons with transfected non-neuronal cells (Graf et al., 2004; Nam and Chen, 2005). However, the lack of an effect of neurexins on synapse formation is consistent with the finding that deletion of α-neurexins does not decrease the number of excitatory synapses, and only moderately decreases the number of inhibitory synapses (Missler et al., 2003).

Moreover, we detected an apparently postsynaptic effect of neurexins, whereas neurexins are thought to function primarily presynaptically. However, our study shows that postsynaptically expressed neurexins act in the postsynaptic neuron only after transport to the cell-surface, and thus may in fact mimic a presynaptic effect.

Furthermore, we propose that the observed effect of neurexins is independent of neuroligins, whereas most processes connected to neurexins can be accounted for by their binding to neuroligins. Indeed, because neurexins can be observed postsynaptically, they were speculated to be postsynaptic regulators of neuroligins (Taniguchi et al., 2007). However, there is no reason why neurexins should not bind to other proteins besides neuroligins (e.g., see Ko et al., 2009a; de Wit et al., 2009), and neuroligins also have neurexin-independent functions (Ko et al., 2009b).

Finally, our current results differ from those obtained with α-neurexin KO mice (Missler et al., 2003; Kattenstroth et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2006). Here, we observed a selective effect of neurexins on inhibitory synapses (i.e., it is not simple synapse damage) that is mediated by an extracellular cell-surface interaction of neurexins with postsynaptic neurons. In contrast, in the KO studies we found an essential function of α-neurexins in organizing neurotransmitter release from all presynaptic nerve terminals. However, a specific change in inhibitory synaptic transmission would have been unobservable in α-neurexin KO mice (Missler et al., 2003) because these mice exhibit an overwhelming impairment in neurotransmitter release which would have occluded a separate facilitation of inhibitory synapses. Moreover, the continued expression of β-neurexins in these mice may have prevented manifestation of an inhibitory synapse phenotype. Thus, despite their differences, it seems likely that the two approaches revealed distinct parts of the overall picture of neurexin function.

Physiological significance

Our data suggest that neurexins decrease GABAergic synaptic transmission by direct binding to GABAA-receptors on the cell surface at the synapse, and that neurexins act by impeding the functional maturation of GABAergic synapses, not their initial formation. Thus, the effects of excess neurexins observed in our experiments may reflect a function of neurexins in regulating GABAergic synapse maturation. We propose that this newly observed activity is one facet of multiple actions of neurexins at synapses, and that presynaptic neurexins likely constitute master regulators of synapse maturation (or validation) via trans-synaptic interactions with an array of postsynaptic targets, which are only now slowly being discovered, as exemplified by the identification of LRRTMs as novel neurexin ligands (Ko et al., 2009a; de Wit et al., 2009). Teasing apart the physiological importance of the various interactions will require definition of neurexin mutations that specifically and selectively impair one interaction without affecting others, since the example of the α-neurexin KO mice has already demonstrated that global ablation of neurexin expression is too blunt an instrument in order to define the full range of neurexin functions. However, the present observations uncovering a very robust action of neurexins on postsynaptic GABAA-receptors extend and expand the emerging concept that neurexins function not in the initial establishment of synapses, but in shaping their properties, in their maturation. A key observation in this regard is the developmental effect of neurexins in the assays described here, which clearly shows that once synapses are formed, they are immune from the effect of overexpressed neurexins. Since synapses are likely continuously formed throughout adult life, this developmental action naturally continues beyond the actual development of the organism, and corroborates the notion of neurexins as key regulators of synaptic properties.

We propose that the effect of neurexins on postsynaptic GABAA-receptors observed here is likely trans-synaptic. However, independent of whether the interaction of neurexins with GABAA-receptors is postsynaptic or trans-synaptic, our findings may shed light on the role of neurexins in cognitive diseases such as autism, addiction, and schizophrenia (Szatmari et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2008; Marshall et al., 2008; Zahir et al., 2008; Kirov et al., 2008; Rujescu et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2008; Hishimoto et al., 2007; Lachman et al., 2007; reviewed in Südhof, 2008). In these disorders, changes in inhibitory synaptic transmission are thought to play a major role. Specifically, alterations in the levels of GABA and GABA-receptors (including GABAAα1) in autistic patients, and mutations in genes expressing GABA receptor subunits (Collins et al., 2006; Fatemi et al., 2008) suggest that the GABAergic system may be centrally involved in autism. Additionally, extensive studies have indicated that mutations in GABAAα1-receptor genes are associated with schizophrenia (Petryshen et al., 2005). In view of the fact that deletions of neurexin-1 α are also associated with autism and schizophrenia (Szatmari et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2008; Marshall et al., 2008; Zahir et al., 2008; Kirov et al., 2008; Rujescu et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2008; Hishimoto et al., 2007; Lachman et al., 2007), and that neurexin-1α KO mice exhibit traits resembling schizophrenia (Etherton et al., 2009), our observation that neurexins physically and functionally interact with GABAA-receptors raise the tantalizing possibility that alterations in GABAergic synaptic transmission may contribute to a convergent mechanism for increasing the risk of autism and schizophrenia.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Expression Vectors

Various vectors were produced using standard molecular biology procedures (see Table S4 and Supplementary Methods).

Neuronal cultures and Ca2+-phosphate transfections

Primary hippocampal neurons were cultured on poly-D-lysine-coated glass coverslips from 1–3 day old mice (Maximov et al., 2007), and transfected with various vectors at DIV10 using a Ca2+-phosphate transfection method (see Supplementary Methods). As visualized by the co-transfected CFP,1–2 % of neurons were typically transfected.

Lentiviral Infection

Lentiviruses were produced by transfecting HEK293 cells (CRL-11268, ATCC) with the respective pFUGW vectors and two helper plasmids (pVSVg and pCMVΔ8.9). Viruses were harvested 48 hr after transfection by collecting the medium from transfected cells. Neurons were infected with 0.2–0.5 ml conditioned HEK293 cell medium for each 24-well of high-density neurons at DIV1-2, and the medium was exchanged to normal growth medium at DIV4, then kept until DIV13 DIV15 for biochemical and electrophysiological analyses. For all experiments, expression of exogenous proteins in neurons was confirmed by immunoblotting and GFP fluorescence.

Immunofluorescence analyses were performed as described (Chubykin et al., 2007), and analyzed blindly using the NIH ImageJ program.

Electrophysiological Recordings were performed as described (Maximov and Sudhof, 2005; Maximov et al., 2007) using a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices). Synaptic responses were evoked by 0.5 ms current injections (90~100 μA) with an Isolated Pulse Stimulator (Model 2000, A-M Systems, Inc.) using a concentric bipolar electrode (FHC, CBAEC75) that was placed at a ~100 μm distance from the patched neuron. The RRP was measured by perfusion of hypertonic sucrose (0.5 M) into the bath solution at 2 ml/min. Series resistance was compensated to 60%–70%, and recordings with series resistances of >20 MΩ were rejected. Data were analyzed using Clampfit 9.02 (Molecular Devices) and Igor 4.0 (Wavemetics).

Recombinant proteins

Ig-neurexins were produced in transfected COS cells and bacterial recombinant proteins were generated and purified as described (Boucard et al., 2005; Hata et al., 1996; Araç et al., 2007; see Supplementary Methods).

Protein interaction measurements using affinity chromatography, pulldowns, and surface plasmon resonance experiments

Affinity-chromatography experiments were performed with proteins solubilized in Triton X-100 from rat brain or from transfected HEK293 cells (Ichtchenko et al., 1995; see Supplementary Methods). Surface Plasmon Resonance measurements were performed with the recombinant extracellular N-terminal regions of the neurexin-1β (Araç et al., 2007) and of the rat GABAAα1-receptor (residues 28–251) essentially as described (Araç et al., 2007; Garboczi et al., 1996; see Supplementary Methods).

Miscellaneous

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting experiments, including quantitation with 125I-labeled secondary antibodies followed by PhosphorImager detection (Molecular Dynamics), were performed as described (Tabuchi et al., 2007). Most antibodies employed were previously characterized (Ichtchenko et al., 1995; Song et al., 1999; Sugita et al., 2001; Ushkaryov et al., 1992) or purchased (GABAAα1 antibodies from Santa Cruz [sc-7348, dilution 1:200], or Alomone Labs [AGA-001, 1:200]). HEK293 cells stably expressing GABAA-receptors were obtained from the ATCC (CRL-2029). All HEK293 and COS cell transfections were performed using FUGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science).

Statistical analyses

All data were generated in at least three independent experiments, and are shown as means ± SEMs. Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t test or the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Robert L. Macdonald (Vanderbilt University) and Dr. Stephen Moss (Tufts University) for gifts of valuable reagents. This paper was supported by grants from the NIMH (MH52804 to T.C.S.) and the Simons Foundation (to T.C.S.), and fellowships from the Life Sciences Research Foundation (to D.A.) and the Human Frontier Science Program Organization (to J.K.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Araç D, Boucard AA, Özkan E, Strop P, Newell E, Südhof TC, Brunger AT. Structures of Neuroligin-1 and the Neuroligin-1/β-Neurexin-1 complex reveal specific protein-protein and protein-Ca2+ interactions. Neuron. 2007;56:992–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner S, Littleton JT, Broadie K, Bhat MA, Harbecke R, Lengyel JA, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Prokop A, Bellen HJ. A Drosophila neurexin is required for septate junction and blood-nerve barrier formation and function. Cell. 1996;87:1059–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Russell RJ, Jackson CJ, Vidovic M, Ganeshina O, Oakeshott JG, Claudianos C. Bridging the synaptic gap: neuroligins and neurexin I in Apis mellifera. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucard AA, Chubykin AA, Comoletti D, Taylor P, Südhof TC. A splice code for trans-synaptic cell adhesion mediated by binding of neuroligin 1 to α- and β-neurexins. Neuron. 2005;48:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih B, Afridi SK, Clark L, Scheiffele P. Disorder-associated mutations lead to functional inactivation of neuroligins. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(14):1471–1477. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih B, Gollan L, Scheiffele P. Alternative splicing controls selective trans-synaptic interactions of the neuroligin-neurexin complex. Neuron. 2006;51:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubykin AA, Atasoy D, Etherton MR, Brose N, Kavalali ET, Gibson JR, Südhof TC. Activity-dependent validation of excitatory versus inhibitory synapses by neuroligin-1 versus neuroligin-2. Neuron. 2007;54:919–931. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubykin AA, Liu X, Comoletti D, Tsigelny I, Taylor P, Südhof TC. Dissection of synapse induction by neuroligins: effect of a neuroligin mutation associated with autism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22365–22374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colavita A, Tessier-Lavigne M. A Neurexin-related protein, BAM-2, terminates axonal branches in C. elegans. Science. 2003;302:293–296. doi: 10.1126/science.1089163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AL, Ma D, Whitehead PL, Martin ER, Wright HH, Abramson RK, Hussman JP, Haines JL, Cuccaro ML, Gilbert JR, Pericak-Vance MA. Investigation of autism and GABA receptor subunit genes in multiple ethnic groups. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:167–174. doi: 10.1007/s10048-006-0045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comoletti D, Flynn RE, Boucard AA, Demeler B, Schirf V, Shi J, Jennings LL, Newlin HR, Südhof TC, Taylor P. Gene selection, alternative splicing, and post-translational processing regulate neuroligin selectivity for beta-neurexins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12816–12827. doi: 10.1021/bi0614131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J, Sylwestrak E, O’Sullivan ML, Otto S, Tiglio K, Savas JN, Yates JR, 3rd, Comoletti D, Taylor P, Ghosh A. LRRTM2 interacts with Neurexin1 and regulates excitatory synapse formation. Neuron. 2009;64:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etherton MR, Blaiss CA, Powell CM, Südhof TC. Mouse neurexin-1alpha deletion causes correlated electrophysiological and behavioral changes consistent with cognitive impairments. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:17998–8003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910297106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Thuras PD. GABAA-Receptor Downregulation in Brains of Subjects with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0646-7. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MJ, Shen W, Song L, Macdonald RL. Endoplasmic reticulum retention and associated degradation of a GABAA receptor epilepsy mutation that inserts an aspartate in the M3 transmembrane segment of the alpha1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37995–38004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garboczi DN, Utz U, Ghosh P, Seth A, Kim J, VanTienhoven EA, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Assembly, specific binding, and crystallization of a human TCR-alphabeta with an antigenic Tax peptide from human T lymphotropic virus type 1 and the class I MHC molecule HLA-A2. J Immunol. 1996;157:5403–5410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf ER, Zhang X, Jin SX, Linhoff MW, Craig AM. Neurexins induce differentiation of GABA and glutamate postsynaptic specializations via neuroligins. Cell. 2004;119:1013–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata Y, Butz S, Südhof TC. CASK: a novel dlg/PSD95 homolog with an N-terminal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase domain identified by interaction with neurexins. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2488–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02488.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishimoto A, Liu QR, Drgon T, Pletnikova O, Walther D, Zhu XG, Troncoso JC, Uhl GR. Neurexin 3 polymorphisms are associated with alcohol dependence and altered expression of specific isoforms. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2880–2891. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichtchenko K, Hata Y, Nguyen T, Ullrich B, Missler M, Moomaw C, Südhof TC. Neuroligin 1: a splice site-specific ligand for beta-neurexins. Cell. 1995;81:435–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichtchenko K, Nguyen T, Südhof TC. Structures, alternative splicing, and neurexin binding of multiple neuroligins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2676–2682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie M, Hata Y, Takeuchi M, Ichtchenko K, Toyoda A, Hirao K, Takai Y, Rosahl TW, Südhof TC. Binding of neuroligins to PSD-95. Science. 1997;277:1511–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattenstroth G, Tantalaki E, Südhof TC, Gottmann K, Missler M. Postsynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function requires alpha-neurexins. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:2607–2612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308626100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HG, Kishikawa S, Higgins AW, Seong IS, Donovan DJ, Shen Y, Lally E, Weiss LA, Najm J, Kutsche K, et al. Disruption of neurexin 1 associated with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirov G, Gumus D, Chen W, Norton N, Georgieva L, Sari M, O’Donovan MC, Erdogan F, Owen MJ, Ropers HH, Ullmann R. Comparative genome hybridization suggests a role for NRXN1 and APBA2 in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:458–465. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J, Fuccillo MV, Malenka RC, Südhof TC. LRRTM2 functions as a neurexin ligand in promoting excitatory synapse formation. Neuron. 2009a;64:791–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J, Zhang C, Arac D, Boucard AA, Brunger AT, Südhof TC. Neuroligin-1 performs neurexin-dependent and neurexin-independent functions in synapse validation. EMBO J. 2009b;28:3244–3255. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman HM, Fann CS, Bartzis M, Evgrafov OV, Rosenthal RN, Nunes EV, Miner C, Santana M, Gaffney J, Riddick A, et al. Genomewide suggestive linkage of opioid dependence to chromosome 14q. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1327–1334. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ashley J, Budnik V, Bhat MA. Crucial role of Drosophila neurexin in proper active zone apposition to postsynaptic densities, synaptic growth, and synaptic transmission. Neuron. 2007;55:741–755. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Hong EJ, Pease S, Brown EJ, Baltimore D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science. 2002;295:868–872. doi: 10.1126/science.1067081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Südhof TC. Autonomous function of synaptotagmin 1 in triggering synchronous release independent of asynchronous release. Neuron. 2005;48:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Pang ZP, Tervo DG, Südhof TC. Monitoring synaptic transmission in primary neuronal cultures using local extracellular stimulation. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;161:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CR, Noor A, Vincent JB, Lionel AC, Feuk L, Skaug J, Shago M, Moessner R, Pinto D, Ren Y, et al. Structural variation of chromosomes in autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missler M, Fernandez-Chacon R, Südhof TC. The making of neurexins. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1339–1347. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missler M, Hammer RE, Südhof TC. Neurexophilin binding to alpha-neurexins. A single LNS domain functions as an independently folding ligand-binding unit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34716–34723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missler M, Zhang W, Rohlmann A, Kattenstroth G, Hammer RE, Gottmann K, Südhof TC. α-Neurexins couple Ca2+ channels to synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Nature. 2003;423:939–948. doi: 10.1038/nature01755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam CI, Chen L. Postsynaptic assembly induced by neurexin-neuroligin interaction and neurotransmitter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6137–6142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502038102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Südhof TC. Binding properties of neuroligin 1 and neurexin 1β reveal function as heterophilic cell adhesion molecules. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26032–26039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.26032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzke H, Ernsberger U. Expression of neurexin-1α splice variants in sympathetic neurons: selective changes during differentiation and in response to neurotrophins. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;15:561–572. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peles E, Joho K, Plowman GD, Schlessinger J. Close similarity between Drosophila neurexin IV and mammalian Caspr protein suggests a conserved mechanism for cellular interactions. Cell. 1997;88:745–746. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko AG, Ullrich B, Missler M, Krasnoperov V, Rosahl TW, Südhof TC. Structure and evolution of neurexophilin. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4360–4369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04360.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petryshen TL, Middleton FA, Tahl AR, Rockwell GN, Purcell S, Aldinger KA, Kirby A, Morley CP, McGann L, Gentile KL, et al. Genetic investigation of chromosome 5q GABAA receptor subunit genes in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:1074–1088. 1057. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissner C, Klose M, Fairless R, Missler M. Mutational analysis of the neurexin/neuroligin complex reveals essential and regulatory components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15124–15129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801639105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissone A, Monopoli M, Beltrame M, Bussolino F, Cotelli F, Arese M. Comparative genome analysis of the neurexin gene family in Danio rerio: insights into their functions and evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:236–252. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowen L, Young J, Birditt B, Kaur A, Madan A, Philipps DL, Qin S, Minx P, Wilson RK, Hood L, Graveley BR. Analysis of the human neurexin genes: alternative splicing and the generation of protein diversity. Genomics. 2002;79:587–597. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozic-Kotliroff G, Zisapel N. Ca2+-dependent splicing of neurexin IIalpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rujescu D, Ingason A, Cichon S, Pietilainen OP, Barnes MR, Toulopoulou T, Picchioni M, Vassos E, Ettinger U, Bramon E, et al. Disruption of the neurexin 1 gene is associated with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn351. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiffele P, Fan J, Choih J, Fetter R, Serafini T. Neuroligin expressed in nonneuronal cells triggers presynaptic development in contacting axons. Cell. 2000;101:657–669. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80877-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JY, Ichtchenko K, Südhof TC, Brose N. Neuroligin-1 is a postsynaptic cell-adhesion molecule of excitatory synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:1100–1105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455:903–911. doi: 10.1038/nature07456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita S, Khvochtev M, Südhof TC. Neurexins are functional α-latrotoxin receptors. Neuron. 1999;22:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80704-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita S, Saito F, Tang J, Satz J, Campbell K, Südhof TC. A stoichiometric complex of neurexins and dystroglycan in brain. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari P, Paterson AD, Zwaigenbaum L, Roberts W, Brian J, Liu XQ, Vincent JB, Skaug JL, Thompson AP, Senman L, et al. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet. 2007;39:319–328. doi: 10.1038/ng1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi K, Südhof TC. Structure and evolution of neurexin genes: insight into the mechanism of alternative splicing. Genomics. 2002;79:849–859. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi K, Blundell J, Etherton MR, Hammer RE, Liu X, Powell CM, Südhof TC. A neuroligin-3 mutation implicated in autism increases inhibitory synaptic transmission in mice. Science. 2007;318:71–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1146221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H, Gollan L, Scholl FG, Mahadomrongkul V, Dobler E, Limthong N, Peck M, Aoki C, Scheiffele P. Silencing of neuroligin function by postsynaptic neurexins. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2815–2824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0032-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich B, Ushkaryov YA, Südhof TC. Cartography of neurexins: more than 1000 isoforms generated by alternative splicing and expressed in distinct subsets of neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:497–507. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushkaryov YA, Hata Y, Ichtchenko K, Moomaw C, Afendis S, Slaughter CA, Südhof TC. Conserved domain structure of β-neurexins. Unusual cleaved signal sequences in receptor-like neuronal cell-surface proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11987–11992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushkaryov YA, Petrenko AG, Geppert M, Südhof TC. Neurexins: synaptic cell surface proteins related to the α-latrotoxin receptor and laminin. Science. 1992;257:50–56. doi: 10.1126/science.1621094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushkaryov YA, Südhof TC. Neurexin IIIα: extensive alternative splicing generates membrane-bound and soluble forms. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:6410–6414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqueaux F, Aramuni G, Rawson RL, Mohrmann R, Missler M, Gottmann K, Zhang W, Südhof TC, Brose N. Neuroligins determine synapse maturation and function. Neuron. 2006;51:741–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqueaux F, Jamain S, Brose N. Neuroligin 2 is exclusively localized to inhibitory synapses. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:449–456. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T, McClellan JM, McCarthy SE, Addington AM, Pierce SB, Cooper GM, Nord AS, Kusenda M, Malhotra D, Bhandari A, et al. Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia. Science. 2008;320:539–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1155174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Lyon T, Skolnick P. Chronic exposure to benzodiazepine receptor ligands uncouples the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor in WSS-1 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:1056–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Noltner K, Feng J, Li W, Schroer R, Skinner C, Zeng W, Schwartz CE, Sommer SS. Neurexin 1α structural variants associated with autism. Neurosci Lett. 2008;438:368–370. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahir FR, Baross A, Delaney AD, Eydoux P, Fernandes ND, Pugh T, Marra MA, Friedman JM. A patient with vertebral, cognitive and behavioural abnormalities and a de novo deletion of NRXN1α. J Med Genet. 2008;45:239–243. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.054437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Sun M, Liu L, Chen F, Wei L, Xie W. Neurexin-1 is required for synapse formation and larvae associative learning in Drosophila. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2509–2516. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Sharpe CR, Simons JP, Gorecki DC. The expression and alternative splicing of α-neurexins during Xenopus development. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:39–46. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052068zz. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Rohlmann A, Sargsyan V, Aramuni G, Hammer RE, Südhof TC, Missler M. Extracellular domains of α-neurexins participate in regulating synaptic transmission by selectively affecting N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4330–4342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0497-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Milunsky JM, Newton S, Ko J, Zhao G, Maher TA, Tager-Flusberg H, Bolliger MF, Carter AS, Boucard AA, Powell CM, Südhof TC. A neuroligin-4 missense mutation associated with autism impairs neuroligin-4 folding and endoplasmic reticulum export. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10843–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1248-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.