Abstract

Objective To assess the salt content of hot meals served at the institutions of salt policy makers in the Netherlands.

Design Observational study.

Setting 18 canteens at the Department of Health, the Health Council, the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority, university hospitals, and affiliated non-university hospitals.

Intervention A standard hot meal collected from the institutional staff canteens on three random days.

Main outcome measure Salt content of the meals measured with an ion selective electrode assay.

Results The mean salt content of the meals (7.1 g, SE 0.2 g) exceeded the total daily recommended salt intake of 6 g and was high at all locations: 6.9 g (0.4 g) at the Department of Health and National Health Council; 6.0 g (0.9 g) at the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority; 7.4 g (0.5 g) at university hospital staff canteens; and 7.0 g (0.3 g) at non-university hospital staff canteens. With data from a national food consumption survey, the estimated total mean daily salt intake in people who ate these meals was 15.4 g. This translates into a 23-36% increase in premature cardiovascular mortality compared with people who adhere to the recommended levels of salt intake.

Conclusion If salt policy makers eat at their institutional canteens they might consume too much salt, which could put their health at risk.

Introduction

Excess salt intake is estimated to cause 30% of all hypertension, and many countries have nationwide programmes to reduce salt intake.1 2 3 4 5 6 We investigated how much salt might be consumed by policy makers if they eat at their institutions’ canteens.

Methods

Network of stakeholders

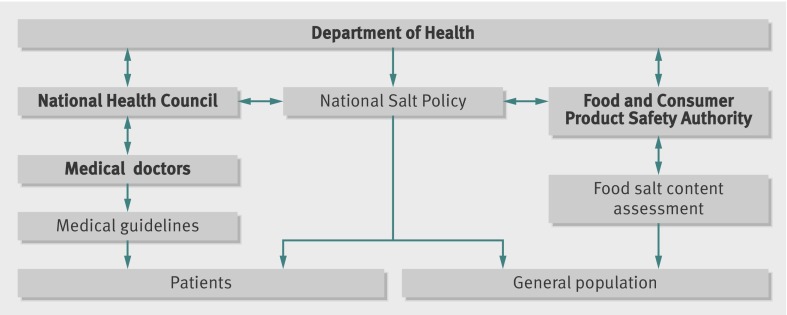

We focused on policy makers (figure)7 because we assumed they would have a greater awareness of the risk of high salt intake and a sense of urgency, combined with power and legitimacy, to formulate guidelines for salt reduction.

Network analysis of salt policy makers

In the Netherlands the Department of Health receives advice from the National Health Council, an independent scientific organisation. It advised the Department of Health to reduce the recommended salt intake in the general population to 6 g a day8 and recommended that the food industry reduce the salt content of commercially available prepared food voluntarily. Such food is monitored by the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority. The advice is implemented in the National Prevention of Disease Act, which is used by doctors in university and non-university hospitals to formulate guidelines on reduction of salt intake.

Locations and consent

Meals were collected at 18 locations in the Netherlands (see table). We did not inform the hospitals but had to notify the security services of the Department of Health, the Health Council, and the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority that we would visit the building. We were allowed to make unannounced visits to the staff restaurant without revealing our objectives.

Collection and analysis

We collected a typical hot lunch (soup and the non-vegetarian hot dish) at each location on three separate randomly chosen weekdays. All canteens visited provided only one non-vegetarian option, served in standard portions. For full details of salt analysis see the appendix on bmj.com. After the collection, we asked whether the policy makers had an institutional salt policy and whether they had outsourced catering or provided it locally. We also randomly sampled 100 employees and asked them how often they ate the hot lunch provided and the type of meal they ate for dinner at home after they had had the hot lunch.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the mean total salt content, rather than the sodium content of the hot meals, according to NICE guidelines.3 Other outcomes were the salt content per 100 g meal and the salt content at different locations. We first calculated the mean salt content at separate locations and tested for heterogeneity before pooling the data. We also used a national food consumption survey to obtain a detailed description and quantification of foods, recipes, and supplements consumed during the preceding day.9 With these data we estimated the probable average daily salt intake of a person who ate the lunch, using data on food intake for the rest of the day from the survey and the employees’ questionnaire, assuming similar salt intake at the weekends.10 We used this estimated total salt intake to determine the probable associated health risk of eating in this way4 11 Data are expressed as means and standard errors. All analyses were done with SPSS version 16.0 (Chicago, IL).

Results

The mean salt content of the hot meals analysed was 7.1 g (SE 0.2), ranging from 5.3 g (0.7) to 9.0 g (2.4), with a median value of 7.0 g (table). There was no heterogeneity in the means between institutions. The mean salt content of the meals exceeded the recommended total daily allowance of 6 g. Of the 54 meals collected, 36 (67%) contained more than 6 g of salt.

Mean salt content of staff meals at institutions of salt policy makers, including academic medical centres and affiliated hospitals in same region

| Location | Salt content | |

|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean (SE) | |

| Ministry of Health and National Health Council* | 6.5-7.3 | 6.9 (0.2) |

| Food Consumer Product Safety Authority*† | 5.0-6.8 | 6.0 (0.5) |

| Academic Medical Centre: | ||

| Amsterdam 1*† | 5.2-11.0 | 7.5 (1.8) |

| Affiliated hospital | 4.9-9.5 | 7.4 (1.4) |

| Amsterdam 2* | 6.9-9.6 | 8.2 (0.8) |

| Affiliated hospital | 5.3-10.2 | 7.0 (1.6) |

| Groningen | 5.6-8.1 | 6.8 (0.7) |

| Affiliated hospital | 5.9-10.6 | 8.1 (1.4) |

| Leiden | 4.8-13.1 | 9.0 (2.4) |

| Affiliated hospital | 5.1-9.3 | 7.1 (1.2) |

| Maastricht | 4.2-6.6 | 5.3 (0.7) |

| Affiliated hospital | 5.2-8.1 | 6.3 (0.9) |

| Nijmegen | 5.2-6.8 | 5.9 (0.5) |

| Affiliated hospital | 5.3-6.7 | 5.9 (0.4) |

| Rotterdam | 6.1-10.5 | 8.2 (1.3) |

| Affiliated hospital | 5.4-7.9 | 6.7 (0.7) |

| Utrecht | 6.6-10.7 | 8.5 (1.2) |

| Affiliated hospital* | 7.3-8.1 | 7.7 (0.2) |

*External food service provider.

†Institution stated to have policy to reduce salt intake.

The salt content averaged 6.5 g (0.4) in non-medical settings versus 7.2 g (0.3) in hospitals; 7.0 g (0.2) in non-academic hospitals versus 7.4 g (0.5) in academic hospitals; and 7.1 g (0.3) in the 13 locations with local catering versus 7.3 g (0.4) with outsourced catering. Only two university hospitals and the Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority had a policy on salt restriction. The salt content of the lunches from these institutions was 7.2 g (0.3) versus 7.1 g (0.6) in those without such a policy. We found similar direction and magnitude of outcomes per 100 g meal (data not shown).

Of the interviewed employees, 63 out of 100 ate the hot meal at work. Of these, 40 (63%) had another hot meal for dinner at home that day. We used these data, and data from the National Food Consumption Survey,9 to estimate the daily salt intake, based on 63% of the people eating another standard dinner at home in the evening and the remainder eating a standard bread meal.9 In people who ate the hot lunch, the estimated daily mean salt intake was 15.4 g (9.4 g higher than the recommended 6 g). Salt intake tends to be similar or higher at weekends,10 and we used a conservative estimate of overconsumption of 9 g a day to estimate health outcomes based on systematic reviews.4 11

Results in context

In a meta-analysis of longer term trials, He and MacGregor studied the dose-response between salt reduction and fall in blood pressure and compared this with two well controlled studies of three different levels of salt intake.11 All three studies showed a consistent dose-response to salt reduction within the range of 3-12 g a day. A reduction of 3 g a day predicted a fall in blood pressure of 3.6-5.6 mm Hg systolic and 1.9-3.2 mm Hg diastolic in people with hypertension and 1.8-3.5 mm Hg and 0.8-1.8 mm Hg, respectively, in those with normal blood pressure. The effect would be doubled with a reduction of 6 g a day and tripled with a reduction of 9 g a day. A conservative estimate indicated that a reduction of 3 g a day would reduce strokes by 13% and ischaemic heart disease by 10%. The effects would be almost doubled with a reduction of 6 g a day and tripled with a reduction of 9 g a day. Reducing salt intake by 9 g a day could reduce strokes by about a third and ischaemic heart disease by a quarter. Other recent meta-analyses studied smaller decreases in salt (2.0-2.3 g) and found less impressive effects.12 13

Thus, overconsumption of 9 g of salt could translate into an average increase in systolic blood pressure in those with hypertension of 11-17 mm Hg, with a diastolic increase of 6-10 mm Hg. In people with normal blood pressure, the estimated systolic increase is 5-11 mm Hg, and diastolic 3-5 mm Hg,11 with the greatest rises predicted to occur in older people and in black people.4 If people eat the meals served at the institutions we studied, they run an estimated increase in cardiovascular risk of 32-36% more deaths from stroke and 23-27% more deaths from coronary heart disease compared with people who adhere to the guidelines.4 11

Discussion

It is impossible for salt policy makers to adhere to their guidelines for salt intake if they eat the hot lunch provided in their workplaces. The mean salt content of the meal alone exceeded the total daily allowance, translating into up to a 36% increase in mortality compared with adherence to the guideline.

Details of the strengths and limitations of our study are in the appendix on bmj.com.

Comparison with other studies

We could not find any published studies on salt content of meals served at staff canteens in institutions of people who make policy on salt intake. The workplace is an understudied location for assessment of salt intake. In our study, 63% of the employees indicated that they ate the hot lunch at work, and it is estimated that public sector organisations provide around one in three meals eaten outside the home.3 Hence, an effective way to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease would be to improve the nutritional quality of the food at work.3 The major contributors to dietary salt intake are commercially prepared foods, including those from restaurants and food service operators,3 which account for around 75% of the sodium intake.14

Guideline implementation

To comply with the recommendation to reduce salt intake, one needs to be first aware of it, then intellectually agree with it before deciding to adopt it and adhere to it.15 The salient stakeholders pair high awareness, agreement, and adoption of the salt policy with power to change guidelines, a sense of urgency, and legitimacy to act.7 Still, the salt policy makers’ institutions do not adhere to the guidelines. The fact that restaurant food is not labelled could contribute to this. Clear labelling helps stakeholders and consumers to make informed choices, and can encourage manufacturers and restaurants to reformulate foods high in salt and other unhealthy constituents.3 In many countries, however, there is no labelling of food in restaurants, and restaurant owners are expected to reformulate their products voluntarily.3 16 17 Our data show that, at least in the offices of the stakeholders, this goal has not been met.

Adam DiChiara after Vincent van Gogh

Conclusions and policy implications

Reduction of salt intake is a cost effective measure to reduce blood pressure and the effects of hypertension, the greatest risk factor for premature death worldwide.3 6 Our data indicate that even salt policy makers cannot adhere to a low salt diet if they consume the hot lunch at work. Consuming these high salt meals translates into a 23-36% increase in premature cardiovascular mortality. These data underline the urgency to remove the exemption of nutrition labelling for food products intended solely for use in restaurants and foodservice operations.

What is already known on this topic

High salt intake is estimated to cause 30% of all hypertension

Ministries of health often initiate and coordinate the development of policies to reduce salt intake, involving governmental and non-governmental stakeholders including the medical profession

What this study adds

Meals served at staff restaurants of salient stakeholders contain high levels of salt, leading to an estimated daily salt intake of more than 15 g (2.5 times the recommended limit), translating into a 23-36% increase in risk of cardiovascular mortality

Even for people who make the policy, salt policies are difficult to adhere to, particularly if they eat food in staff restaurants and canteens

Contributors: LMB and GAvM designed the study after eating very salty meals in staff canteens at their own and other academic institutions. CAB collected the meals. LMB, CAB, and GAvM monitored the data collection and designed the methods for analyses. LMB and CAB cleaned and analysed the data, and this was monitored by GAvM. LMB wrote the introduction, methods, results and discussion, and designed the figure. CAB and GAvM helped to write and revise the paper. LMB is guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: None required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d7352

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Details of salt analysis and strengths and limitations of study

References

- 1.Appel LJ, Frohlich ED, Hall JE, Pearson TA, Sacco RL, Seals DR, et al. The importance of population-wide sodium reduction as a means to prevent cardiovascular disease and stroke: a call to action from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;123:1138-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reducing salt intake in populations: report of a WHO forum and technical meeting, 5-7 October 2006 Paris, France. World Health Organization, 2007. www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/reducingsaltintake_EN.pdf.

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Prevention of cardiovascular disease at population level. NICE, 2010.

- 4.Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, Moran A, Lightwood JM, Pletcher MN, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2010;362:590-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, Adams C, Alleyne G, Asaria P, for the Lancet NCD Action Group; NCD Alliance. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet 2011;377:1438-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Hoorn SV, Murray CJL, for the Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 2002;360:1347-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell RK, Agle BR, Wood DJ. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who or what really counts. Acad Manage Rev 1997;22:853-86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Council of the Netherlands. Guidelines for a healthy diet. 2006. www.gezondheidsraad.nl/en/publications/guidelines-healthy-diet-2006-0.

- 9.Hulshof KFAM, Ocké MC, van Rossum CTM, Buurma-Rethans EJM, Brants HAM, Drijvers JJMM, Ter Doest D. Resultaten van de Voedselconsumptiepeiling 2003. RIVM/TNO, 2004 [in Dutch].

- 10.Shortt C, Flynn A, Morrissey PA. Assessment of sodium and potassium intakes. Eur J Clin Nutr 1988;42:605-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He FJ, MacGregor GA. How far should salt intake be reduced? Hypertension 2003;42:1093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor RS, Ashton KE, Moxham T, Hooper L, Ebrahim S. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (Cochrane Review). Am J Hypertens 2011;24:843-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He FJ, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet 2011;378:380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattes RD, Donnelly D. Relative contributions of dietary sodium sources. J Am Coll Nutr 1991;10:383-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathman DE, Konrad TR, Freed GL, Freeman VA, Koch GG. The awareness-to-adherence model of the steps to clinical guideline compliance. Med Care 1996;34:873-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Drug administration. Office of Nutrition, Labeling, and Dietary Supplements. Guidance for industry: a labeling guide for restaurants and other retail establishments selling away-from-home foods. FDA, 2008. www.fda.gov/food.

- 17.European Commission, Directorate General Health, Consumers Directorate C “Health and Risk Assessment”. Evaluation of the European platform for action on diet, physical activity and health. Case report: food/drink reformulation. European Union, 2010. http://ec.europa.eu/health/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/evaluation_case2_en.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Details of salt analysis and strengths and limitations of study