Abstract

Objective To test the “27 club” hypothesis that famous musicians are at an increased risk of death at age 27.

Design Cohort study using survival analysis with age as a time dependent exposure. Comparison was primarily made within musicians, and secondarily relative to the general UK population.

Setting The popular music scene from a UK perspective.

Participants Musicians (solo artists and band members) who had a number one album in the UK between 1956 and 2007 (n=1046 musicians, with 71 deaths, 7%).

Main outcome measures Risk of death by age of musician, accounting for time dependent study entry and the number of musicians at risk. Risk was estimated using a flexible spline which would allow a bump at age 27 to appear.

Results We identified three deaths at age 27 amongst 522 musicians at risk, giving a rate of 0.57 deaths per 100 musician years. Similar death rates were observed at ages 25 (rate=0.56) and 32 (0.54). There was no peak in risk around age 27, but the risk of death for famous musicians throughout their 20s and 30s was two to three times higher than the general UK population.

Conclusions The 27 club is unlikely to be a real phenomenon. Fame may increase the risk of death among musicians, but this risk is not limited to age 27.

Introduction

The recent tragic death of the singer Amy Winehouse, aged 27, reignited talk of the “27 club”, as a seemingly unusual number of well known musicians have died at this age.1 A rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle is often associated with excess drinking and taking psychoactive drugs. These behaviours greatly increase the risk of death from an accident or overdose,2 3 but why would these deaths occur specifically at age 27? One explanation might be that musicians often become famous in their early twenties, and their risk taking peaks four to five years later. Another explanation is that joining the 27 club has become attractive to musicians who want to be more famous (whether consciously or subconsciously), and hence their risky behaviour peaks at this age, or they may even commit suicide at 27. An alternative explanation is that the 27 club exists by chance and is an example of confirmation bias, where people focus on results that support their hypothesis and ignore those that refute it.4 5

We investigated whether a true increase in risk exists by creating a retrospective cohort of famous musicians and using survival analysis to search for a peak in risk at age 27.

Methods

Sampling scheme

We aimed to create a cohort of famous musicians with an unbiased and transparent sampling scheme. We defined famous musicians as those who had had a number one album in the UK charts. We chose the UK charts because they were a long running and reasonably consistent marker of success. For musicians in bands, we sampled all the band members listed on the album. We collected data from 1956, when the UK charts began, until the end of 2007. The first number one was Frank Sinatra’s Songs for Swingin’ Lovers! on 28 July 1956, and the last number one was Leona Lewis’ Spirit on 18 November 2007.

We obtained data from Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org) using the lists of number one albums by decade. In a test of 42 scientific articles, Wikipedia had a similar accuracy to Encyclopaedia Britannica.6 We took a simple random sample of 48 musicians using a random number generator in the R software, and verified the Wikipedia date of birth as correct (using biographies or official web sites) for 41 (85%). Two dates (4%) had differences of less than six months, and for the remaining five (10%) no confirmatory date could be found.

For each musician we recorded their date of birth, date of number one, and date of death. Musicians who were still alive were censored on 1 August 2011, two weeks before the data were extracted. The date of number one was used as the time dependent study entry and the date from which musicians were at risk (when their fame began). Musicians who became famous after age 27 cannot be part of the 27 club, but their data are still useful for estimating the overall mortality curve. For musicians with multiple number one albums we used the earliest album. Musicians in our cohort were at risk after their first number one album, in the same way that a patient is at risk of a ventilator associated pneumonia after being ventilated.7

We excluded 114 musicians with no recorded date of birth, and five unlucky musicians with posthumous number one albums (as they were never alive and famous according to our definition).

Statistical methods

We used a Lexis diagram to display all data by calendar time and age at death.8 We also plotted the number of deaths for each age (in whole years), the number of musicians at risk, and the death rate per 100 musician years. This was to show the number and rate of deaths at age 27 compared with other years, and the denominator of the number at risk.

To estimate the death rates per 100 musician years we used a survival analysis with age as a time dependent exposure.9 To give any potential peak in risk at age 27 a high chance of being found, we smoothed the death rates using a natural spline for age and tested models with two to 12 degrees of freedom.10 The higher the degrees of freedom, the more flexible the spline and hence the greater chance of the model finding a “bump” in the risk. However, more degrees of freedom also mean a more complex model. Therefore, we compared the fit of the models using the Akaike information criterion.11 The model was fitted using a Poisson distribution with age as the independent variable.

For comparison with musician death rates, we drew the death rates per 100 person years in the UK population by decade of birth. We made this comparison to check that there was no peak in death rates in the UK population at age 27, which would be repeated in our musician cohort. These data were from a publicly available database (the human mortality database from University of California and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research at www.mortality.org, downloaded 11 August 2011).

All analyses were done using R with the Epi and MVNA packages. All the data used were publicly available, and no ethics applications were made.

Results

Our final sample contained 1046 musicians, with 71 deaths (7%). The sample included crooners, death metal stars, rock ‘n’ rollers, and even Muppets (the actors, not the puppets). The sample consisted mostly of men (899, 86%). The median age at first number one was 26 years (inter-quartile range 23 to 30 years). The total follow-up time was 21 750 musician years, with an average per musician of 21 years.

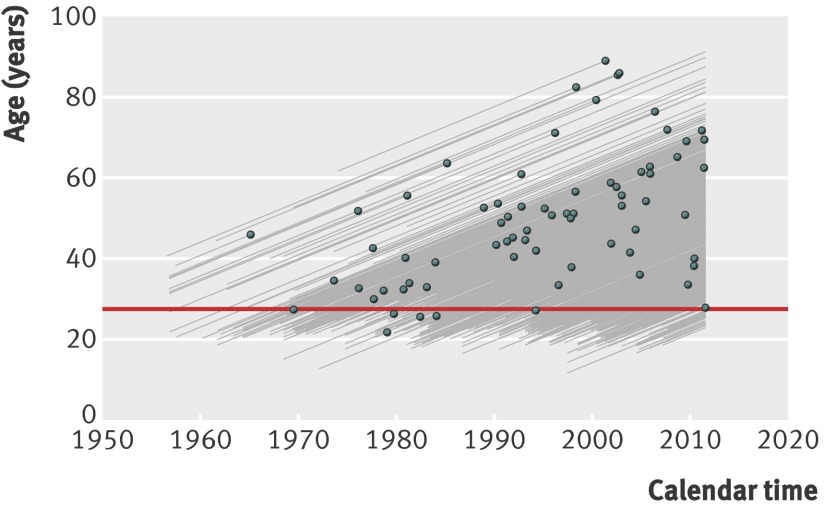

The Lexis diagram shows the lifetime of every musician (fig 1). For example, the highest line shows a musician who had a number one in 1974 aged 61, and who died in 2001 aged 88 (Perry Como). This lifetime highlights that not all musicians in our cohort were at risk at age 27, because their first number one occurred when they were older. We repeated all the analyses using a subcohort of musicians who had a number one album before age 28 (624 musicians, 60%), which gave similar results and conclusions.

Fig 1 Lexis diagram of musicians with a number one UK album from 1956 to 2007. Each grey line shows a musician’s lifetime, starting at their number one album and ending in their death (points) or censoring in 2011

Our sample contained only three deaths at age 27 (in 1969, 1994, and 2011), but there were a few near misses in the late 1970s and early 1980s. We noted a group of relatively young deaths (ages 20 to 40) in the 1970s and early 1980s, followed by an absence of deaths in this age group from 1985 to 1992 despite there being many musicians at risk. There were no deaths at any age between 1985 and 1987.

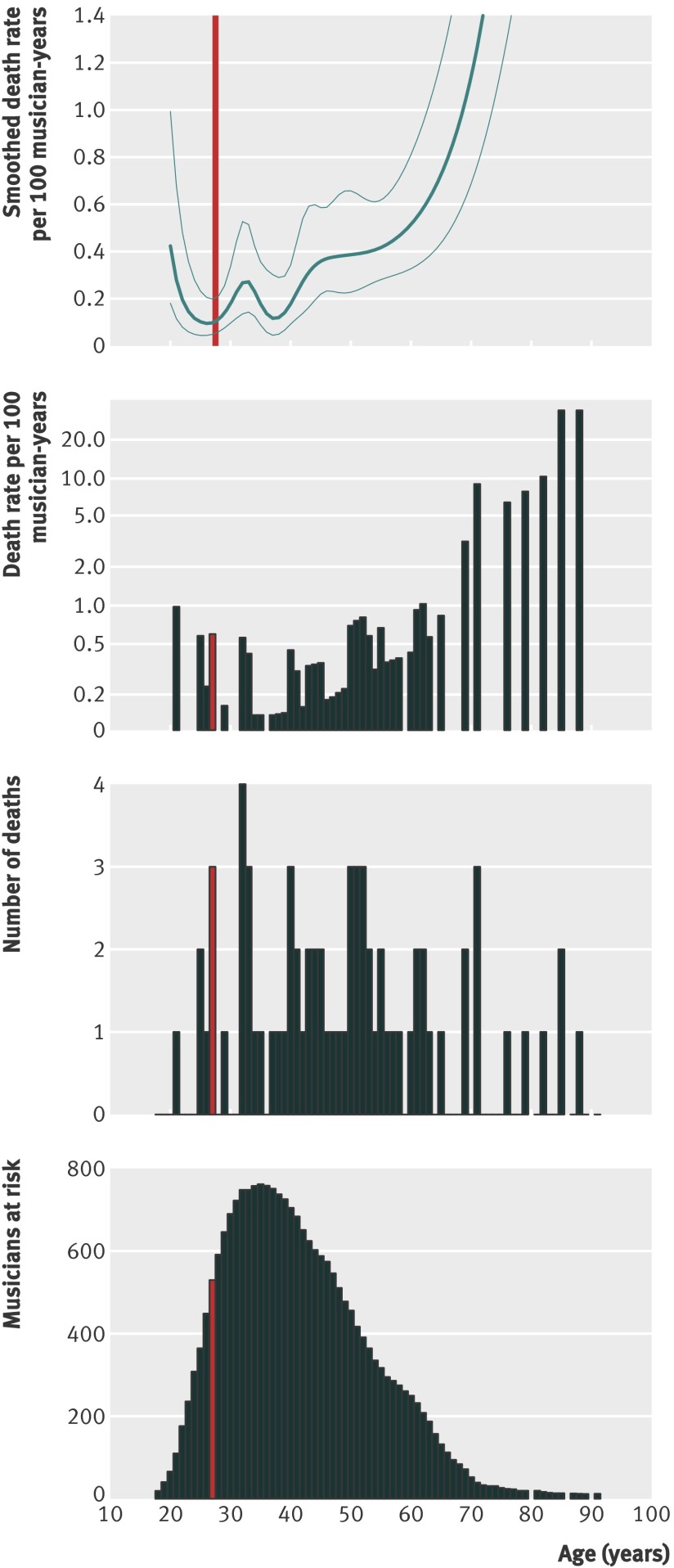

Figure 2 shows the number of deaths at each age and the number of musicians at risk. The death rates per 100 musician years were calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the number of musicians at risk and multiplying by 100. There were three deaths at age 27 amongst 522 musicians at risk, giving a death rate of 0.57 per 100 musician years. Similar death rates were observed at ages 25 (rate=0.56) and 32 (rate=0.54). The smoothed death rate shows a peak at age 32 and no peak at age 27. Risk increased greatly after age 60. The best fit for the smoothed death rate (smallest Akaike information criterion) used seven degrees of freedom.

Fig 2 Smoothed mean death rate per 100 musician years using a spline with a 95% confidence interval (top), mean death rate per 100 musician-years (second from top) number of deaths (third from top), and number of musicians at risk (bottom) by age in years. Age 27 is marked in red. Y axis for smoothed death rates restricted to 0 to 1.4 to focus on the ages of interest. Y axis for mean death rates is on log scale to focus on younger ages

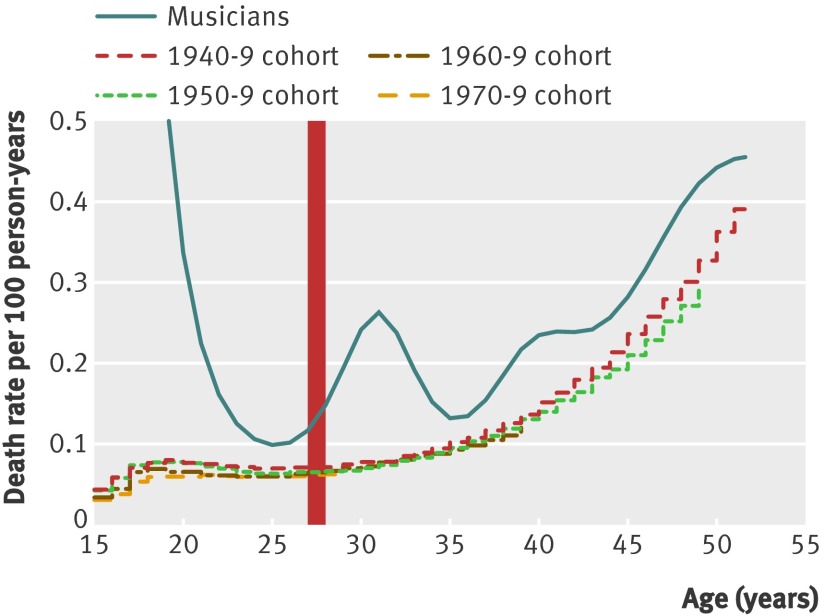

Figure 3 shows the death rates in the general UK population by decade of birth, and the smoothed death risk from the top panel of figure 2. Death rates in the UK show the well known steady increase in risk with ageing, and the reduction in risk for younger cohorts. Death rates for the cohort of famous musicians during their 20s and 30s were two to three times higher than in the UK population.

Fig 3 Deaths rates in the general UK population per 100 person years by age and decade of birth (cohort) for ages 18 to 50, and smoothed death rate per 100 musician years. Vertical red line indicates age 27, with no increase in risk. Each cohort’s line ends at the age where no more data are available

Discussion

Our analysis found no peak in the risk of death for musicians at age 27, despite using a flexible spline model that would have allowed even a small bump in risk to appear. The study indicates that the 27 club has been created by a combination of chance and cherry picking.

We found some evidence of a cluster of deaths in those aged 20 to 40 in the 1970s and early 1980s. This pattern was particularly striking because there were no deaths in this age group in the late 1980s, despite the great number of musicians at risk. This difference may be due to better treatments for heroin overdose, or the change in the music scene from the hard rock 1970s to the pop dominated 1980s.

Limitations

Our sampling scheme only captured three of the seven most famous 27 club members (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Club_27), as one fell outside our time period (Robert Johnson, who died in 1938), and three did not have a number one UK album (Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison). We used a clear, specific, and measurable a priori definition of fame, rather than working backwards from the known 27 club members, an approach that had the potential to create a biased sample. Our a priori definition in combination with a cohort design allows the calculation of our main outcome: death rates in famous musicians by age.12 Although we only captured three of the seven famous 27 club members, we did capture seven Muppets.

Not the 27 club: Brian Jones, Amy Winehouse, Kurt Cobain

Dezo Hoffmann/Rex; Yui Mok/PA; KMazur/WireImage/Getty Images

The 114 (10%) musicians with no recorded date of birth were likely to be less famous (for example, bass players and backing singers). If these people had died in tragic or dramatic circumstances (especially at age 27), then their birth and death dates would probably have been recorded in Wikipedia. If these musicians are more likely to be alive than the musicians with recorded dates, then our estimated musicians’ death rate will be too high.

Our definition of fame was based on a number one album in the UK, so our conclusions only hold for musicians famous in the UK. Results may be different for other settings, such as the US music scene, especially if the trappings and pressures of fame differ by country. Other studies based on alternative definitions of fame are needed before we can definitively state that the 27 club is a chance finding. Two example definitions are: using a number one UK single rather than album, which would capture one-hit wonders; and using a number one album in the US, which would examine the consequences of being famous in the US.

We compared the death rates of musicians from multiple countries with death rates based on UK population data. The higher rate of deaths in musicians should therefore be interpreted in light of this mismatch in populations (although most of the musicians were from western countries, with broadly similar death rates to the UK). The comparison to the general UK population might be also prone to information bias,12 as the death rates were obtained from different sources.

Conclusion

The myth of the 27 club supposes that musicians are more likely to die aged 27, whereas our results show that they have a generally increased risk throughout their 20s and 30s. This finding should be of international concern, as musicians contribute greatly to populations’ quality of life, so there is immense value in keeping them alive (and working) as long as possible.

What is already known on this subject

The notion of the “27 club”—a group of well known musicians who died at age 27—has led some to believe that a high risk of death among musicians at this age is a real phenomenon

What this study adds

Famous musicians do not have an increased risk of death at age 27, but they do have a generally increased risk of death during their 20s and 30s compared with the UK population

Thorough statistical analysis is essential before apparently unusual clusters of deaths are declared real

We thank Cunrui Huang for entering the data and Jan Beyersmann for discussions about the sampling scheme.

Contributors: MW, AA, and AGB had the original idea and designed the sampling scheme. MW, AA, and AGB ran the statistical analyses with input from NG. AGB wrote the first draft with critical input from MW and NG. AGB is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Consent was not obtained but the presented data are anonymised.

Data sharing: Statistical code and data are available at www.hlth.qut.edu.au/ph/about/staff/barnett/MusicianFiles.zip with open access.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d7799

References

- 1.Segalstad E, Hunter J. The 27s: the greatest myth of rock and roll. North Atlantic Books, 2009.

- 2.Howland J, Hingson R. Alcohol as a risk factor for drownings: a review of the literature (1950-1985). Accid Anal Prev 1988;20:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darke S, Zador D. Fatal heroin “overdose”: a review. Addiction 1996;91:1765-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blastland M, Dilnot A. The Tiger that isn’t: seeing through a world of numbers. Profile; 2008.

- 5.Goldacre B. Bad science: quacks, hacks, and big pharma flacks. Faber and Faber, 2010.

- 6.Giles J. Internet encyclopaedias go head to head. Nature 2005;438:900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenthal V, Udwadia F, Muñoz H, Erben N, Higuera F, Abidi K, et al. Time-dependent analysis of extra length of stay and mortality due to ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive-care units of ten limited-resources countries: findings of the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC). Epidemiol Infect 2011;139:1757-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keiding N. Statistical inference in the Lexis diagram. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London series A: physical and engineering sciences 1990;332:487-509. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyersmann J, Allignol A, Schumacher M. Competing risks and multistate models. Springer, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Ruppert D, Wand M, Carroll R. Semiparametric regression. Cambridge series on statistical and probabilistic mathematics. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- 11.Burnham K, Anderson D. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Springer; 2002.

- 12.Grimes D, Schulz K. Cohort studies: marching towards outcomes. The Lancet 2002;359:341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]