Host–guest systems that display catalytic behavior represent a promising area of supramolecular chemistry.[1] Supramolecular approaches to cataylst design include ligand-templated encapsulation,[2] self-assembled ligands, coordination compounds, and artificial biomacromolecules.[3] Generally, these systems operate by binding substrates and stabilizing transition states and/or increasing the effective concentration of reactive species within confined space.[4] In most catalytic host–guest systems the substrate is a guest and substrates that adequately fill the host’s interior are required to ensure activity. Alternatively, there are few instances where the guest is the catalyst.[5] These examples incorporate transition metal guests and enhanced reaction rates are rare.[6] Here we report a complementary approach where the bound guest is an organocatalyst in a deep cavitand. We find that the cavitand/piperidinium complex accelerates the Knoevenagel condensation and show that the rate of the reaction can be controlled using light to stimulate structural changes in the cavitand’s shape.

Relatively few examples of photo-switchable catalysis have been described,[7] but our recent experience with photo-controlled guest binding in a cavitand with an azo wall provided an encouraging point of departure.[8] For the present investigation we used short hydrocarbon chains (C2) on the “feet” to facilitate crystallization and incorporated an isopropyl substituent onto the azo wall (Scheme 1). The azo group can be photo-isomerized between trans (with 448 nm light) and cis (with 365 nm light) configurations. In the trans resting state the cavitand presents a cavity accessible to guests; in the cis configuration a self-fulfilling introverted arrangement results (Figure 1). This invagination imparts unusual stability to the cis-1 isomer: it shows a t1/2 at room temperature of more than 75 days.

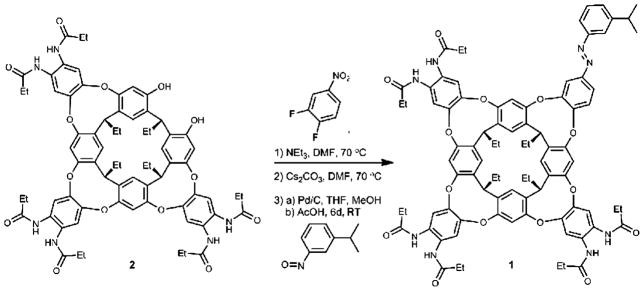

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of light-responsive cavitand 1.

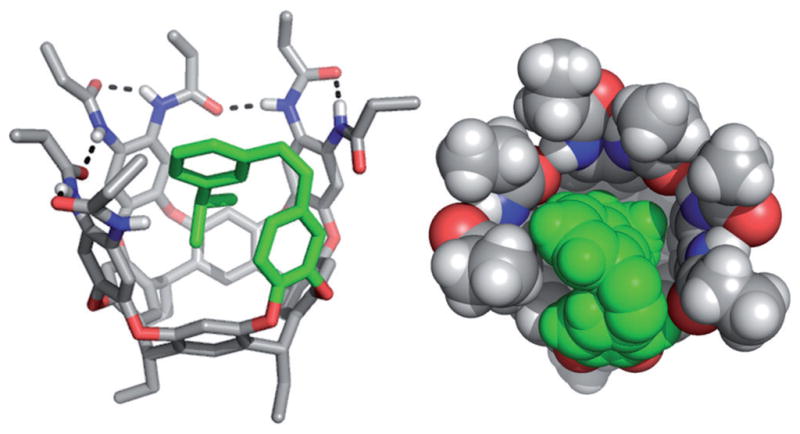

Figure 1.

Stick and CPK representations of the introverted cis-1 crystal structure viewed from the side (left) and the top (right). The introverted azo wall is colored green.

The synthesis of 1 was achieved in three steps from known hexa-amide diol 2. The azo wall of the cavitand was installed in two parts by coupling 3,4-difluoronitrobenzene, first using triethylamine as the base followed by cesium carbonate. Subsequently, the nitro group was reduced to an amine then immediately condensed with 3-isopropylnitrosobenzene in glacial acetic acid. The iPr azo cavitand 1 is a yellow solid, isolated in 37% yield from hexaamide diol 2 and exists as a mixture of trans and cis isomers.

The extreme conformational stability of cis-1 allowed for structural characterization in the solid state that is quite uncommon for cis-azo compounds.[9] Single, red crystals of 1 were grown by diffusing pentane into an acetone solution after UV irradiation. Cis-1 crystallizes in the C2/c space group with one cavitand in the asymmetric unit and 8 molecules per unit cell.[10] Both enantiomers were observed and modeled accordingly. The cavitand adopts an introverted conformation with the iPr group penetrating the cavity stabilized by CH–π contacts ranging from 3.0 to 3.9 Å (Figure 1 and Figure S4 in the Supporting Information). The azo geometry is distorted to maximize contacts with the interior of the cavitand with average ∢CCNN =58° and ∢NNC =123° (53.3° and 121.9° respectively for cis-azobenzene).[11]

Knoevenagel reported that formaldehyde and diethyl malonate could be condensed using diethylamine as the catalyst.[12,13] The Knoevenagel condensation was extended to include other active methylene compounds reacting with aldehydes or ketones and became a reliable method for preparing carbon–carbon bonds. This reaction is still employed in the synthesis of natural products, drugs, dyes and other compounds.[13] and an asymmetric variant has recently been achieved.[14] Other secondary amines and their salts catalyze this reaction and, depending on the conditions and substrates, the reaction proceeds through a Hann-Lapworth[15] (β-hydroxy intermediate, I) mechanism and/or a Knoevenagel (iminium intermediate, II) mechanism (Scheme 2).[13,16] Piperidine or piperidinium salts are popular catalysts for the reaction.

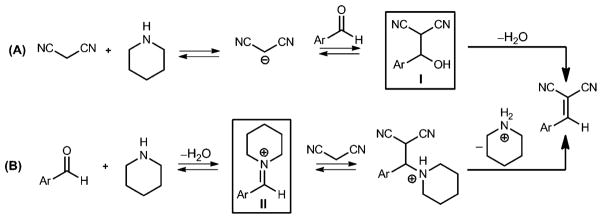

Scheme 2.

Two possible mechanisms for secondary amine-catalyzed Knoevenagel condensations. Counter ions are omitted for simplicity.

The cavitand 1 binds piperidinium acetate in a variety of organic solvents. In [D4]acetic acid trans-1 exhibits a dynamic vase conformation on the NMR time scale, as revealed by the broad methine protons of the resorcin[4]arene. When piperidinium acetate is introduced, trans-1 folds around the catalyst forming a vase conformation with sharp NMR signals. An association constant Ka of 4300 m−1 was determined. Separate signals for free and bound piperidinium indicate slow exchange on the NMR time scale and 2D EXSY experiments reveal the barrier to be 17.8 kcalmol−1.[17] Irradiation with UV light (365 nm) isomerizes the azo wall of the cavitand to the cis configuration and this has a remarkable effect—the cavitand assumes an introverted conformation projecting the iPr substituent into the cavity (Figure 1) and ejecting the piperidinium acetate into solution.

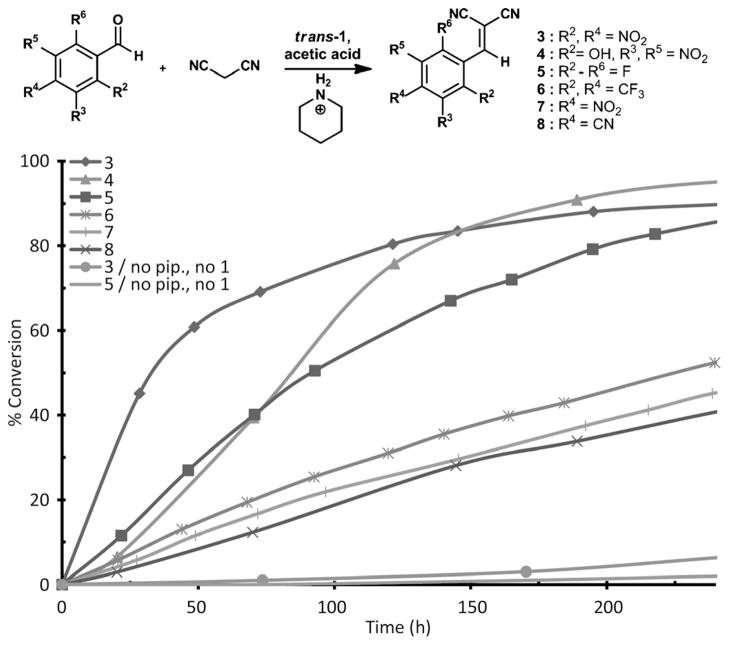

Surprisingly, cavitand 1 promotes the piperidinium acetate-catalyzed Knoevenagel condensation between malononitrile and aromatic aldehydes (Figure 2, inset). The uncatalyzed reaction is quite slow in [D4]acetic acid. After 240 h little reaction occurs and only 7% or less of the olefin product is observed (Figure 2). The reaction is significantly accelerated by the host–guest complex: piperidinium acetate (5 mol%) and trans-1 (5–13 mol%).[18] The host binds the piperidinium catalyst and not the substrate. As a result, the catalyzed reaction tolerates a range of aromatic aldehydes that do not fit into the cavity.

Figure 2.

Graph depicting % conversions of cavitand 1/piperidinium-catalyzed Knoevenagel condensations of aromatic aldehydes at room temperature.

The supramolecular assembly appears necessary for the rate enhancement. Comparison of the reaction rates in the presence and absence of trans-1 highlights the importance of the cavitand/catalyst complex (Table 1). Cavitand 1 produces up to 3.5-fold increase in the initial reaction rate (kHG/kCAT) as compared to the reaction with piperidinium alone (kCAT).[19] NOESY NMR experiments and magnetic anisotropy induced changes to chemical shifts reveal that piperidinium acetate binds to trans-1 with the nitrogen near the open end of the cavitand. This orientation surrounds the catalyst with a structured semi-circle of hydrogen bonding secondary amides. In this system we observe the buildup of a β-hydroxy intermediate (Scheme 2, I).[20] It is likely that the polar amide groups facilitate deprotonation of the malononitrile nucleophile which quickly reacts with the aldehyde to produce the olefin product—outside the cavitand. Neither the condensation product nor the substrates are guests and the catalyst is the only species observed in the cavitand during the reaction.[21]

Table 1.

Comparison of the rate constants[a] involving the host–guest complex (kHG) and the piperidinium-catalyzed reaction (kCAT).

| Aldehyde | kHG/kCAT |

|---|---|

| 3 | 3.0 |

| 4 | n.d.[b] |

| 5 | 3.5 |

| 6 | 2.3 |

| 7 | 2.6 |

| 8 | 2.1 |

The reactions are second order and initial rates were used with the same time interval for both rate constant calculations.

Reaction abides by different reaction kinetics and was not compared.

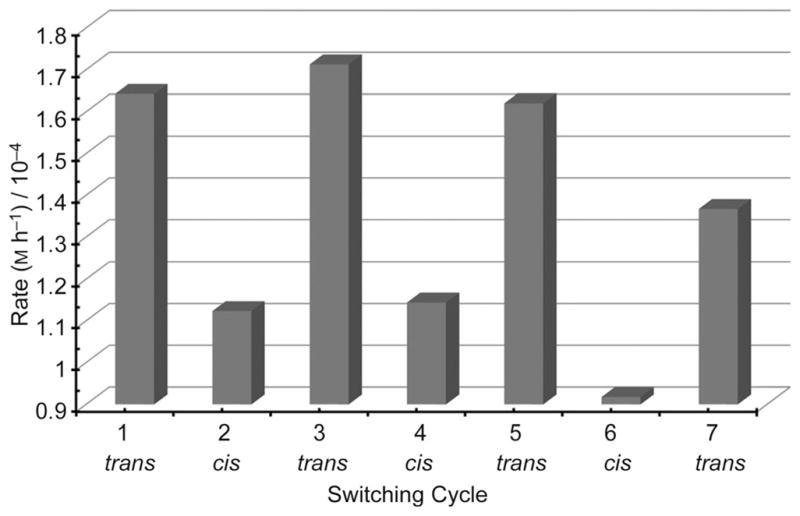

The azo wall of 1 allows control of guest binding and as an example, we reacted pentafluorobenzaldehyde (5) with malononitrile in the presence of piperidinium acetate and the cavitand. At set time intervals the cavitand was photo-isomerized between the trans and cis configurations and the reaction rates were measured between isomerizations (Figure 3). The reaction is accelerated by trans-1 and decelerated by cis-1, consistent with the removal of the catalyst from the host.[22] This process is reversible and numerous cycles were followed without loss of function (Supporting Information). A control experiment excluding 1 did not respond to light.

Figure 3.

Photo-controlled catalysis of the Knoevenagel condensation between 5 and malononitrile with the 1/piperidinium catalyst complex.

In summary, the Knoevenagel condensation of aromatic aldehydes with malononitrile is accelerated and catalyzed by a light responsive cavitand/piperidinium complex. In this example the cavitand binds the catalyst itself, and the rate of the reaction can be manipulated with light. Photo-controlled reactivity is a viable approach to supramolecular catalysis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We are grateful to the Skaggs Institute and the NIGMS (GM 27953) for financial support. A Ruth L. Kirschstein Postdoctoral fellowship for O.B.B. was provided by NIH (F32GM087068). A.C.S. is a Skaggs Pre-doctoral Fellow. We would also like to thank Prof. Arnie Rheingold and Milan Gembicky for assistance with the X-ray structure.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201105374.

Contributor Information

Dr. Orion B. Berryman, The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037 (USA)

Aaron C. Sather, The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037 (USA)

Agustí Lledó, Research Unit of Asymmetric Synthesis (URSA), Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB), Baldiri Reixach 10, Barcelona 08028 (Spain).

Prof. Julius Rebek, Jr., The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037 (USA).

References

- 1.a) Pluth MD, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1650–1659. doi: 10.1021/ar900118t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yoshizawa M, Tamura M, Fujita M. Science. 2006;312:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1124985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Kleij AW, Reek JNH. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:4218–4227. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Slagt VF, Kamer PCJ, Van Leeuwen PWNM, Reek JNH. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1526–1536. doi: 10.1021/ja0386795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Leeuwen PWMN. Supramolecular Catalysis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2008. [Google Scholar]; Van Leeuwen PWMN. In: Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry. Reinhoudt DN, editor. Vol. 10. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Breiner B, Clegg JK, Nitschke JR. Chem Sci. 2011;2:51–56. [Google Scholar]; b) Minten IJ, Claessen VI, Blank K, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM, Cornelissen JJLM. Chem Sci. 2011;2:358–362. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Cavarzan A, Scarso A, Sgarbossa P, Strukul G, Reek JNH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2848–2851. doi: 10.1021/ja111106x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fiedler D, Leung DH, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:349–358. doi: 10.1021/ar040152p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Leung DH, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2746–2747. doi: 10.1021/ja068688o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sarmentero MA, Fernandez-Perez H, Zuidema E, Bo C, Vidal-Ferran A, Ballester P. Angew Chem. 2010;122:7651–7654. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:7489–7492. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Brown CJ, Miller GM, Johnson MW, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11964–11966. doi: 10.1021/ja205257x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Bai S, Yang H, Wang P, Gao J, Li B, Yang Q, Li C. Chem Commun. 2010;46:8145–8147. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01401j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang ZJ, Brown CJ, Bergman RG, Raymond KN, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7358–7360. doi: 10.1021/ja202055v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niazov T, Shlyahovsky B, Willner I. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6374–6375. doi: 10.1021/ja0707052.Peters MV, Stoll RS, Kuhn A, Hecht S. Angew Chem. 2008;120:6056–6060. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802050.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5968–5972. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802050.for a recent review on all types of photogated catalysis including photoswitchable catalysis see: Stoll RS, Hect S. Angew Chem. 2010;122:5176–5200.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:5054–5075. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000146.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:5054–5075. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000146.Ueno A, Takahashi K, Osa T. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1980:837–838.Ueno A, Takahashi K, Osa T. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1981:94–96.Wei Y, Han S, Kim J, Soh S, Grzybowski BA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11018–11020. doi: 10.1021/ja104260n.Würthner F, Rebek J., Jr Angew Chem. 1995;107:503–505.Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:446–448.

- 8.Berryman OB, Sather AC, Rebek J., Jr Chem Commun. 2011;47:656–658. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03865b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.To highlight this we turned to the CSD (Cambridge Structural Database, Version 5.31, November 2009, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge, CB2 1EZ, UK.). A search of any azobenzene derivative in the CSD with an R factor less than 0.1 resulted in 1096 hits A second search constraining the CNNC dihedral angle to be less than 90° resulted in only 55 hits illustrating that azobenzene structures in the cis conformation are relatively uncommon Furthermore, only 6 structures (plus one solvate) are representatives of cis-azobenzene derivatives free of covalent restrictions Of the 55 hits 13 have the azobenzene tied up as a heterocycle or as the N-oxide 23 are cis-azobenzene derivatives coordinating to metal centers and 10 have the azobenzene derivative as part of a macrocycle (plus one polymorph and solvate)

- 10.Crystal data for cis-1, C97H109N8O16.5, M = 1650.92, monoclinic, C2/c, a =28.7988(12), b =21.3694(9), c =30.4767(13) Å, α = 90.00, β =110.894(2), γ =90.00°, V=17522.4(13) Å3, Z =8, ρcalcd = 1.252 gmL−1, μ (MoKα) = 0.694 mm−1, 2θmax = 55.71°, T=100 K, 60963 reflections collected, R1 =0.1221 for 10800 reflections, Rint = 0.1022 (1099 parameters) with I > 2σ(I), and R1 =0.0945, wR2 =0.3228, GooF =1.542 for all 10800 data, CCDC 842812 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- 11.a) Crecca CR, Roitberg AE. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:8188–8203. doi: 10.1021/jp057413c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mostad A, Roemming C. Acta Chem Scand. 1971;25:3561–3568. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.25-3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knoevenagel E. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1896;29:172.Knoevenagel E. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1898;31:738.Knoevenagel E. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1898;31:2585.Knoevenagel E. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1898;31:2596.e) for an excellent review on the Knoevenagel condensation see reference [13].

- 13.Tietze LF, Beifuss U. Chem Synth. 1991;2:341–388. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee A, Michrowska A, Sulzer-Mosse S, List B. Angew Chem. 2011;123:1745–1748. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1707–1710. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hann ACO, Lapworth A. J Chem Soc. 1904;85:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka M, Oota O, Hiramatsu H, Fujiwara K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1988;61:2473–2479. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renslo AR, Tucci FC, Rudkevich DM, Rebek J., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4573–4582. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Initial test reactions using trans-1 were done with 5.8 mol% and 11 mol% cavitand (see Supporting Information). The reaction with 11 mol% cavitand showed only a 1% increase in overall reaction rate. Nevertheless, further studies were conducted using 9–13 mol% of cavitand.

- 19.For the rate constant calculations inital rates were used with approximately the same time interval for both calculations. Plots of 1/[A] vs time produce linear graphs suggesting that for most of the substrates the reaction is second order (see Supporting Information; A =aldehyde).

- 20.Knoevenagel reactions catalyzed by tertiary amines are known to proceed through the Hann–Lapworth mechanism. The reaction of malononitrile with 3 in the presence of triethylammonium as a catalyst is slightly faster and produced the same intermediate that is observed when piperidinium is used as the catalyst. Triethylamine cannot form an iminium intermediate suggesting that the reaction proceeds through this pathway. Furthermore, this intermediate does not match the spectrum of the iminium obtained from reacting the aldehyde with piperidinium alone.

- 21.An intermediate is observed that does not bind to the cavitand. The intermediate is formed in the presence or absence of cavitand and only when all three components are present (aldehyde, malononitrile and piperidinium). This intermediate is likely the β-hydroxy intermediate (see reference [20]).

- 22.Despite the efficiency of the guest removal upon photoisomerization to cis-1, a small amount of piperidinium acetate remains bound to the cavitand (see Supporting Information). This results in slightly elevated reaction rates as compared to the reaction when the cavitand is absent. In addition, the isomerization from cis-1 to trans-1 reaches a photostationary state of approximately 90% trans-1 leading to depressed reaction rates as compared to the reaction with 100% trans-1.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.