Abstract

Purpose

We hypothesized that surgeons who place shunts infrequently during CEA may have inferior outcomes when shunt use may be required more commonly, such as contralateral carotid occlusion (CCO). Therefore, we studied the association between surgeon practice pattern in shunt placement and 30-day stroke/death in patients undergoing CEA with CCO.

Methods

Among 6,379 CEAs performed in the Vascular Study Group of New England (VSGNE) between 2002-2009, we identified 353 patients who underwent CEA with CCO, and compared 30-day stroke/death rate to 5,279 patients who underwent primary, isolated CEA with a patent contralateral carotid artery. Within patients with CCO, we examined 30-day stroke or death rate across the reason for shunt placement (no shunt, shunt placed routinely, and a shunt placed for an indication) as well as 2 distinct surgeon practice patterns in shunt placement (surgeons who selectively utilize a shunt (0-95% of their CEAs), or routinely utilize a shunt (>95% of their CEAs). We used observed to expected (O/E) ratios to provide risk-adjusted comparisons across groups.

Results

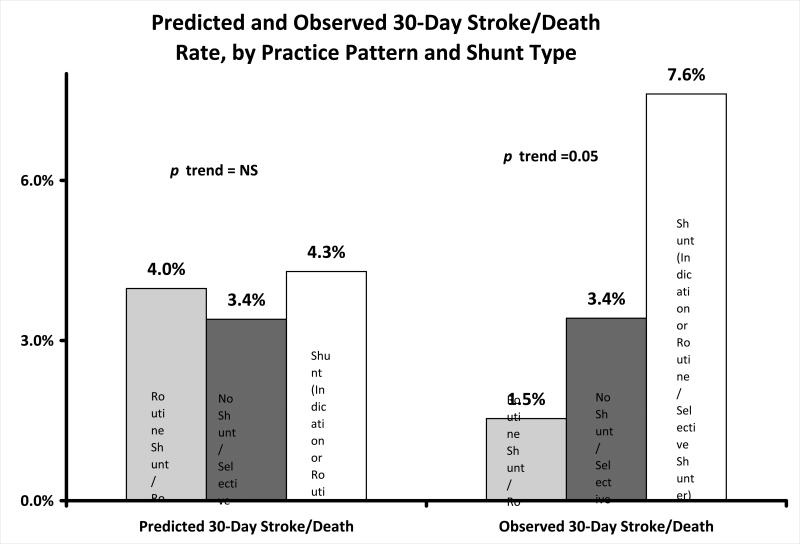

Of 353 patients with CCO, 118 patients (33)% underwent CEA without a shunt, 173 patients (49%) underwent CEA using a shunt placed routinely, and 62 (18%) had a shunt placed for a neurologic indication. There were no differences in rates of 30-day stroke /death across categories of reason for shunt use (3.4% no shunt, 4.0% routine shunt, 4.8% shunt for indication, p=0.891). However, across surgeon practice patterns in shunt use, the risk of 30-day stroke/death was higher for surgeons who selectively placed shunts in all their CEAs, and lower for surgeons who routinely placed shunts (5.6% selective, 1.5% routine, p=0.05). Even when adjusting for patient characteristics, the risk of 30-day stroke/death was higher than 1 in patients undergoing selective shunting (O/E ratio = 1.4, 95% CI 1.1-1.7), and lower than 1 for surgeons who placed shunts routinely (O/E ratio = 0.4, 95% CI 0.2-0.9). Within surgeon practice patterns, stroke/death rates were lowest when individual surgeons’ intra-operative decisions reflected their usual pattern of practice (1.5% stroke/death rate when “routine” surgeons placed a shunt, 3.4% when “selective” surgeons did not place a shunt, 7.6% stroke/death rate for “selective” surgeons placed a shunt, p trend=0.05)

Conclusions

The risk of 30-day stroke/death is higher in patients with CCO than in CEA with a patent contralateral carotid artery, and surgeons who place shunts selectively during CEA have higher rates of stroke/death in patients with CCO. This suggests that shunt use during CEA for CCO is associated with fewer complications, but only if the surgeon uses a shunt as part of their routine practice in CEA. Surgeons should pre-operatively consider their own practice pattern in shunt utilization when faced with a patient who may require shunt placement.

Introduction

Surgical decision-making for patients with severe carotid atherosclerosis is complicated by the presence of a contralateral carotid occlusion (CCO)1-4. Fewer than 10% of CEAs are performed in patients with CCO, limiting the power of most studies to analyze uncommon events such as peri-operative stroke or death. Evaluation of potential methods of risk reduction during CEA with CCO is also challenging, because of the inherent variation in patient risk factors (such as symptomatic or asymptomatic presentation) and surgical technique (such as the use of eversion endarterectomy or patch angioplasty).

Despite these challenges, many believe that using an intra-operative shunt is important for stroke reduction during CEA in patients with CCO. Proponents argue that shunt utilization ensures global perfusion, as evidenced by EEG and stump pressure measurement5. Further, large clinical series have shown excellent outcomes when shunts are placed for CEA in the setting of CCO. However, many surgeons argue that shunts are not routinely necessary, even in the setting of CCO4,6-8. This conclusion is justified by similarly large series case of CEAs, which demonstrate equivalent rates of stroke with and without a shunt, in CEAs with and without CCO9. But in many of these series, CEA is performed by a high-volume surgeon or group of surgeons who rarely place a shunt for any reason. Whether these results can be generalized to broader populations of surgeons and patients is uncertain.

To study the outcomes and optimal management of a large group of patients undergoing CEA in the setting of CCO, we used data from the Vascular Study Group of New England (VSGNE). We examined the outcomes of patients undergoing CEA in the settings of CCO, with a focus on evaluating the effect of different surgeon practice patterns regarding shunt use within the academic and community centers that participate in this regional registry.

Methods

Within the VSGNE, data was prospectively collected by 74 surgeons and associated staff in 12 hospitals (www.vsgne.org) . Hospital data were collected for each patient and periodically audited against claims data to insure entry of all patients. Follow-up data were collected at the time of subsequent outpatient evaluation, with data from the visit closest to one year after surgery entered into the database. Further details on this database have been published previously10, and others are available at www.vsgne.org.

Subjects

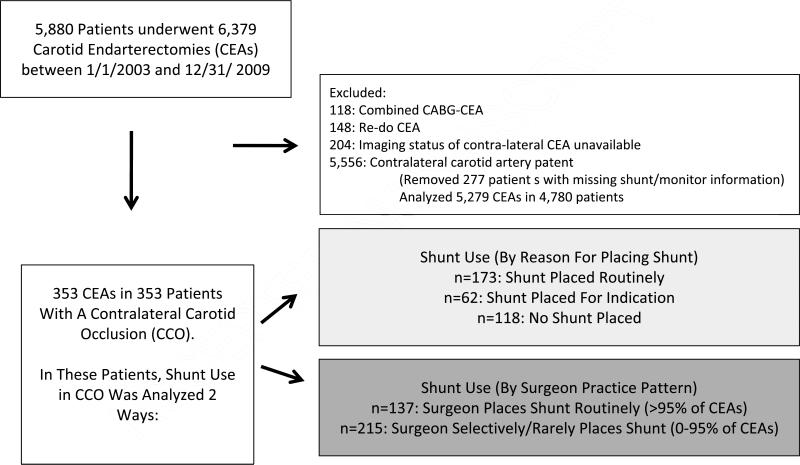

Between January 1st 2003, and December 29, 2009, 5,880 patients underwent 6,379 primary CEAs in New England at one of the 12 centers participating in our registry (Figure 1). Patients without imaging information (either duplex, CT, or MRI) available at the time of surgery were excluded from the analysis (204 of 6,379 CEAs, 3.1% of the total). Patient data was entered into the registry pre-operatively, at discharge, and at one-year follow up. Mean interval follow-up was 13.5 months, (95% CI 12.6-14.5 months).

Figure 1.

Cohort formation.

We excluded all patients who underwent re-do CEA (n=148 CEAs, 2.3% of the total) and combined CABG/CEA (n=118, 1.8% of the total). Our study cohort consisted of all patients with a contralateral carotid occlusion (CCO) documented by pre-operative imaging (n=353). Of the 5,556 CEAs with a patent contralateral carotid artery ( performed in 5,057 patients), details on shunt placement or monitoring information was unavailable in 227 patients (4%). Therefore, our comparison cohort consisted of 5,279 CEAs performed in 4,780 patients with a patent contralateral carotid artery.

Definitions and Exposure Variables

The unit of analysis was the operation. Patients were evaluated for pre-existing medical co-morbidities, and these data were prospectively entered into the registry by specifically trained surgeons, nurses or clinical data abstractors. Over 70 clinical and demographic variables were collected for each patient. Our dataset was audited for completeness of procedural submissions using ICD-9 data from each center10,11.

The main exposure variable was the presence of a CCO, and the secondary exposures were the type of shunt placed and surgeon practice patterns in shunt placement. Demographic data and the incidence of patient-level comorbidities are outlined in Table 1. CEA was categorized as conventional or eversion. Primary versus patch closure of the endarterectomy was recorded, as was other descriptions of operative technique, such as anesthesia type, anticoagulant use, and completion study utilization.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and univariate associations of 30-day stroke or death, by CCO status

| CEA with Contralateral Carotid Occlusion (n=353) | CEA without Contralateral Carotid Occlusion (n=5,279) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % of Total | n | Total N | % of Total | n | Total N | p value |

| Patient characteristics | |||||||

| Male Gender | 72.5 | 282 | 353 | 59.3 | 3210 | 5279 | <0.001 |

| Right Side | 50.6 | 197 | 353 | 49.0 | 2585 | 5279 | 0.445 |

| Non-White Race | 0.8 | 3 | 353 | 1.2 | 61 | 5279 | 0.319 |

| Urgency | |||||||

| Elective | 88.4 | 312 | 353 | 89.5 | 4720 | 5279 | 0.086 |

| Urgent | 11.6 | 41 | 353 | 9.8 | 515 | 5279 | |

| Energent | 0.0 | 0 | 389 | 0.8 | 41 | 5279 | |

| Age | |||||||

| Less than 40 years | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 0.1 | 3 | 5279 | 0.117 |

| Age 40-49 | 4.3 | 15 | 353 | 2.2 | 117 | 5279 | |

| Age 50-59 | 15.3 | 54 | 353 | 12.1 | 638 | 5279 | |

| Age 60-69 | 29.2 | 103 | 353 | 30.9 | 1630 | 5279 | |

| Age 70-79 | 37.7 | 133 | 353 | 38.3 | 2024 | 5279 | |

| Age 80-89 | 13.3 | 47 | 353 | 15.7 | 830 | 5279 | |

| Age 90 or greater | 0.3 | 1 | 353 | 0.7 | 37 | 5279 | |

| Smoking (prior or current) | 90.1 | 318 | 353 | 78.9 | 4153 | 5279 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 29.5 | 104 | 353 | 30.8 | 1623 | 5279 | 0.616 |

| Creatinine >1.8% | 12.2 | 43 | 353 | 8.4 | 443 | 5279 | 0.013 |

| Dialysis | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 0.7 | 38 | 5279 | 0.077 |

| Hypertension | 89.8 | 317 | 353 | 86.7 | 4570 | 5279 | 0.027 |

| Beta blockers | 84.6 | 297 | 353 | 82.5 | 4337 | 5279 | 0.313 |

| Coronary disease | 35.7 | 126 | 353 | 32.4 | 1709 | 5279 | 0.371 |

| Prior CABG or Coronary Intervention | 33.4 | 118 | 353 | 31.5 | 1662 | 5279 | 0.686 |

| Congestive heart failure | 8.0 | 28 | 353 | 7.3 | 385 | 5279 | 0.557 |

| Ipsilateral Degree of stenosis | |||||||

| Ipsilateral <50% stenosis | 0.3 | 1 | 353 | 0.7 | 36 | 5279 | 0.321 |

| Ipsilateral >50% stenosis | 1.7 | 6 | 353 | 1.5 | 79 | 5279 | |

| Ipsilateral >60% stenosis | 3.4 | 12 | 353 | 4.4 | 230 | 5279 | |

| Ipsilateral >70% stenosis | 17.6 | 62 | 353 | 21.4 | 1128 | 5279 | |

| Ipsilateral >80% stenosis | 76.1 | 268 | 353 | 71.3 | 3753 | 5279 | |

| Occluded | 0.9 | 3 | 353 | 0.7 | 35 | 5279 | |

| Contralateral Degree of stenosis | |||||||

| Contralateral <50% stenosis | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 58.5 | 2983 | 5279 | <0.001 |

| Contralateral >50% stenosis | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 11.9 | 606 | 5279 | |

| Contralateral >60% stenosis | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 10.6 | 543 | 5279 | |

| Contralateral >70% stenosis | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 11.8 | 601 | 5279 | |

| Contralateral>80% stenosis | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 7.2 | 369 | 5279 | |

| Occluded | 100.0 | 353 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 5279 | |

| Symptom Status | |||||||

| Cortical Symptoms (TIA or Stroke) | 25.8 | 91 | 353 | 37.2 | 1964 | 5279 | 0.003 |

| Ocular Symptoms | 8.4 | 30 | 353 | 15.3 | 816 | 5279 | <0.001 |

| Ipsilateral Vertebrobasilar Symptoms | 4.9 | 17 | 353 | 2.5 | 130 | 5279 | 0.006 |

| Preoperative Medication Regimen | |||||||

| No Anti-platelet Agent Use | 10.8 | 38 | 353 | 11.1 | 585 | 5279 | 0.020 |

| Anti-platelet Agent Use (aspirin only) | 68.0 | 240 | 353 | 72.9 | 3851 | 5279 | |

| Anti-platelet Agent Use (clopidigrel only) | 4.2 | 15 | 353 | 2.8 | 146 | 5279 | |

| Anti-platelet Agent Use (Aspirin, clopidigrel, or both) | 17.0 | 60 | 353 | 13.0 | 687 | 5279 | |

| Preoperative Statin Use | 77.8 | 274 | 353 | 73.0 | 3850 | 5279 | 0.043 |

| Operative Characteristics | |||||||

| General Anesthesia | 93.5 | 330 | 353 | 87.9 | 4637 | 5279 | <0.001 |

| Shunt Utilization (by procedure) | |||||||

| No shunt placed | 33.4 | 118 | 353 | 53.5 | 2823 | 5279 | <0.001 |

| Routine shunting | 49.0 | 173 | 353 | 41.9 | 2209 | 5279 | |

| Shunting placed for indication | 17.6 | 62 | 353 | 4.6 | 224 | 5279 | |

| Type of Monitoring That Prompted Shunt | |||||||

| EEG | 57 | 192 | |||||

| Awake Patient | 3 | 14 | |||||

| Other (e.g. stump pressure) | 2 | 15 | |||||

| Shunt Utilization (by surgeon practice pattern) | |||||||

| Procedure Performed by Selective Shunter Surgeon | 60.9 | 215 | 353 | 62.1 | 3267 | 5279 | 0.809 |

| Procedure Performed by Routine Shunter Surgeon | 39.1 | 138 | 353 | 37.9 | 1992 | 5279 | |

| Technical Aspects of CEA | |||||||

| Eversion endarterectomy | 9.7 | 34 | 353 | 10.7 | 564 | 5279 | 0.427 |

| Patch angioplasty | 84.4 | 298 | 353 | 84.8 | 4474 | 5279 | 0.999 |

| Protamine | 43.5 | 153 | 353 | 47.1 | 2481 | 5279 | 0.461 |

| Completion study | 36.8 | 130 | 353 | 33.2 | 1751 | 5279 | 0.032 |

Examination of The Decision to Place a Shunt

First, as outlined in Figure 1, with the patient and procedure as the unit of analysis, we categorized shunt use in terms of the manner in which the shunt was placed. In the VSGNE registry, shunt use during CEA is categorized as: not used (none), placed because of routine practice (routine), or placed for some specific indication, such as EEG changes with clamping, observed neurologic changes in an awake patient, or low carotid stump pressure (shunt for indication), Thus, for each CEA, shunt use was categorized as none, routine or for indication.

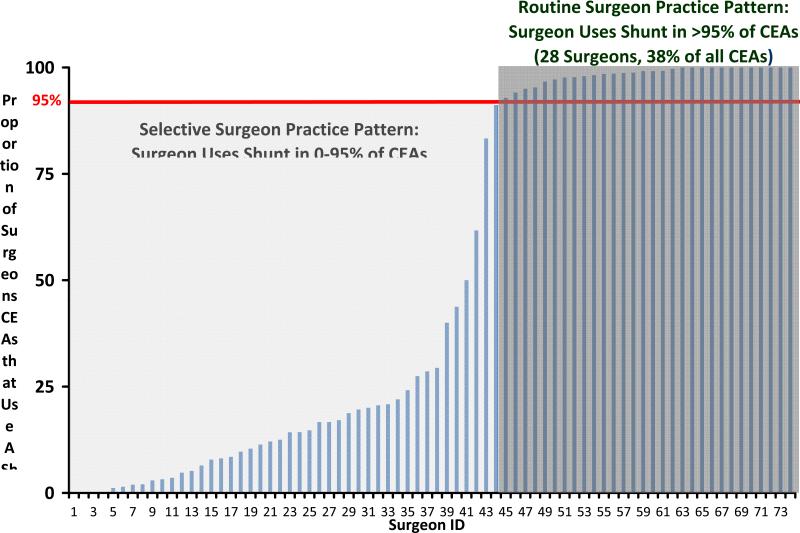

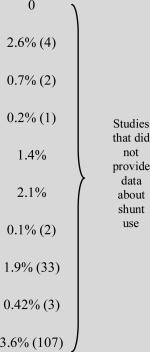

Since we sought to examine surgeon practice patterns in shunt utilization, we then categorized each surgeon according to their practice pattern in CEA. We categorized each surgeon using two mutually exclusive practice patterns: surgeons who routinely utilize a shunt (>95% of all their CEAs), or surgeons who selectively utilize a shunt (0-95% of all their CEAs). These thresholds were established following examination of the practice patterns in shunt use (Figure 2), and a review of current literature12-15. Other thresholds were examined in sensitivity analyses (30%, 50%, 80%, and 90% shunt use) .

Figure 2.

Surgeon practice patterns in shunt utilization.

Outcome Measures

Our main outcome measure was 30-day stroke or death following CEA. In crude analyses, we compared unadjusted rates of 30-day stroke or death following CEA, across patients with and without CCO. Further, within those patients who underwent CEA in the setting of a CCO, we compared crude rates of 30-day stroke or death across type of shunt use (none, routine, shunt for indication) as well as across surgeon practice pattern (routine or selective).

Multivariable Model to Adjust For Pre-Operative \Risk of 30-Day Stroke or Death

After determining the crude rates of thirty-day stroke or death, we compared the crude rates across groups with and without CCO, using observed to expected (O/E) ratios. These O/E ratios were generated by dividing the observed 30-day stroke or death rate by the predicted 30-day stroke or death rate for each group. These predicted risks were generated at the patient level, based on pre-operative patient characteristics, utilizing our VSGNE-specific CEA risk prediction model. This model utilizes pre-operative patient characteristics (urgent need for surgery, symptom status, congestive heart failure, age, and antiplatelet therapy) to predict the risk of stroke or death within 30 days following CEA11. We used this model because it was derived from over 3,000 CEAs undergoing surgery in the VSGNE, and has been internally and externally validated. We then compared predicted and actual rates to provide each groups O/E ratio, with surrounding 95% confidence intervals.

All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) and STATA (College Station, TX). The Institutional Review Board at Dartmouth Medical School reviewed and approved our study protocol.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Overall, patients with CCO were more frequently male (73%), and between the ages of most commonly between the ages of 70-79. Nearly all (99%) were Caucasian (Table 1) and had a history of either prior or current smoking (89%); 91% had hypertension, 30% had diabetes, and 23% had a history of COPD. In terms of symptom status, 54% of patients were symptomatic (39% ipsilateral, 15% contralateral or non-specific), while the remainder (46%) were asymptomatic. Further details about the characteristics of the cohort are available in Table 1.

Patients who underwent CEA for CCO differed from the remaining CEA patients in the VSGNE registry in several ways. Patients with CCO were more commonly male (73% versus 59%), more likely to have a smoking history (90% versus 79%, p<0.001), more likely to have chronic renal insufficiency (12% versus 8%, p=0.013), and more likely to have hypertension (91% versus 87%, p=0.02). However, while patients with CCOs tended to have more comorbidities, they were less likely to have symptoms (CCO = 39% symptomatic, non-CCO 55% symptomatic, p=0.001, Table 1). Lastly, patients with CCO were less likely to undergo surgery without a shunt (33% CCO CEAs performed without a shunt, 54% of non-CCO CEAs performed without a shunt, p<0.001).

Among patients with CCO, there were several differences in shunt use based on patient characteristics (Table 1b). For example, patients in whom a shunt was placed for an indication were more likely to be symptomatic pre-operatively than those in whom no shunt or routine shunting was employed (37% versus 18% versus 27%, respectively, p<0.01). Further, patients who were operated upon urgently were more likely to receive a shunt for indication (26%) versus patients undergoing elective CEA (16%) (p<0.018).

Table 1b.

Patient characteristics and univariate associations of 30-day stroke or death, by type of shunt in CCO patients.

| CEA with Contralateral Carotid Occlusion (n=353) | No shunt (n=118) | Routine Shunt (n=173) | Shunt for Indication (n=62) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % of Total | n | Total N | % of Total | n | Total N | % of Total | n | Total N | % of Total | n | Total N | p value |

| Patient characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Male Gender | 79.8 | 282 | 353 | 77.9 | 92 | 118 | 70.5 | 122 | 173 | 16.7 | 43 | 62 | 0.299 |

| Right Side | 55.8 | 197 | 353 | 47.5 | 56 | 118 | 63.5 | 110 | 173 | 50.0 | 31 | 62 | 0.063 |

| Non-White Race | 0.8 | 3 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 118 | 0.6 | 2 | 173 | 1.6 | 1 | 62 | 0.391 |

| Urgency | 118 | 173 | 62 | ||||||||||

| Elective | 88.4 | 312 | 353 | 94.9 | 112 | 118 | 86.1 | 149 | 173 | 82.3 | 51 | 62 | |

| Urgent | 11.6 | 41 | 353 | 5.1 | 6 | 118 | 13.9 | 24 | 173 | 17.7 | 11 | 62 | |

| Energent | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 118 | 0.0 | 0 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | 0.018 |

| Age | 118 | 173 | 62 | ||||||||||

| Less than 40 years | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 118 | 0.0 | 0 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | |

| Age 40-49 | 4.3 | 15 | 353 | 2.5 | 3 | 118 | 4.1 | 7 | 173 | 8.0 | 5 | 62 | |

| Age 50-59 | 15.3 | 54 | 353 | 16.1 | 19 | 118 | 15.0 | 26 | 173 | 15.3 | 9 | 62 | |

| Age 60-69 | 29.2 | 103 | 353 | 35.6 | 42 | 118 | 27.8 | 48 | 173 | 20.9 | 13 | 62 | |

| Age 70-79 | 37.7 | 133 | 353 | 35.6 | 42 | 118 | 38.2 | 66 | 173 | 40.3 | 25 | 62 | |

| Age 80-89 | 13.3 | 47 | 353 | 10.2 | 12 | 118 | 14.5 | 25 | 173 | 16.1 | 10 | 62 | |

| Age 90 or greater | 0.3 | 1 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 118 | 0.6 | 1 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | 0.535 |

| Smoking (prior or current) | 90.1 | 318 | 353 | 91.5 | 108 | 118 | 87.9 | 152 | 173 | 93.6 | 58 | 62 | 0.356 |

| Diabetes | 29.5 | 104 | 353 | 28.8 | 34 | 118 | 27.2 | 47 | 173 | 37.0 | 23 | 62 | 0.333 |

| Creatinine >1.8% | 12.2 | 43 | 353 | 11.0 | 13 | 118 | 10.4 | 18 | 173 | 19.4 | 12 | 62 | 0.162 |

| Dialysis | 0.0 | 0 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 118 | 0.0 | 0 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | 0.999 |

| Hypertension | 89.8 | 317 | 353 | 91.5 | 108 | 118 | 88.4 | 153 | 173 | 90.3 | 56 | 62 | 0.687 |

| Beta blockers | 84.6 | 297 | 353 | 86.4 | 102 | 118 | 80.1 | 137 | 173 | 93.6 | 58 | 62 | 0.034 |

| Coronary disease | 35.7 | 126 | 353 | 42.4 | 50 | 118 | 32.4 | 56 | 173 | 32.3 | 20 | 62 | 0.179 |

| Prior CABG or Coronary Intervention | 33.4 | 118 | 353 | 42.4 | 50 | 118 | 26.6 | 46 | 173 | 35.5 | 22 | 62 | 0.018 |

| Congestive heart failure | 8.0 | 28 | 353 | 4.2 | 5 | 118 | 9.3 | 16 | 173 | 11.3 | 7 | 62 | 0.166 |

| Ipsilateral Degree of stenosis | 118 | 173 | 62 | ||||||||||

| Ipsilateral <50% stenosis | 0.3 | 1 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 118 | 0.6 | 1 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | |

| Ipsilateral >50% stenosis | 1.7 | 6 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 118 | 3.5 | 6 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | |

| Ipsilateral >60% stenosis | 3.4 | 12 | 353 | 2.5 | 3 | 118 | 5.2 | 9 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | |

| Ipsilateral >70% stenosis | 17.6 | 62 | 353 | 19.5 | 23 | 118 | 16.9 | 29 | 173 | 16.1 | 10 | 62 | |

| Ipsilateral >80% stenosis | 76.1 | 268 | 353 | 78.0 | 92 | 118 | 72.1 | 124 | 173 | 83.9 | 52 | 62 | |

| Occluded | 0.9 | 3 | 353 | 0.0 | 0 | 118 | 1.7 | 3 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | 0.106 |

| Symptom Status | 118 | 173 | 62 | ||||||||||

| Cortical Symptoms (TIA or Stroke) | 25.8 | 91 | 353 | 17.8 | 21 | 118 | 27.2 | 47 | 173 | 37.1 | 23 | 62 | 0.016 |

| Ocular Symptoms | 8.4 | 30 | 353 | 5.0 | 6 | 118 | 10.9 | 19 | 173 | 8.0 | 5 | 62 | 0.394 |

| Ipsilateral Vertebrobasilar Symptoms | 4.9 | 17 | 353 | 2.5 | 3 | 118 | 6.4 | 11 | 173 | 4.8 | 3 | 62 | 0.594 |

| Preoperative Medication Regimen | 118 | 173 | 62 | ||||||||||

| No Anti-platelet Agent Use | 10.8 | 38 | 353 | 11.0 | 13 | 118 | 11.5 | 20 | 173 | 8.0 | 5 | 62 | |

| Anti-platelet Agent Use (aspirin only) | 68.0 | 240 | 353 | 76.3 | 90 | 118 | 61.3 | 106 | 173 | 71.0 | 44 | 62 | 0.997 |

| Anti-platelet Agent Use (clopidigrel only) | 4.2 | 15 | 353 | 2.5 | 3 | 118 | 4.6 | 8 | 173 | 6.5 | 4 | 62 | 0.673 |

| Anti-platelet Agent Use (Aspirin, clopidigrel, or both) | 17.0 | 60 | 353 | 9.3 | 11 | 118 | 24.3 | 42 | 173 | 11.3 | 7 | 62 | 0.083 |

| Preoperative Statin Use | 77.8 | 274 | 353 | 82.2 | 97 | 118 | 77.9 | 134 | 173 | 69.4 | 43 | 62 | 0.143 |

| Operative Characteristics | 118 | 173 | 62 | ||||||||||

| General Anesthesia | 93.5 | 330 | 353 | 85.6 | 101 | 118 | 98.3 | 170 | 173 | 96.2 | 59 | 62 | 0.001 |

| Shunt Utilization (by surgeon practice pattern) | 118 | 173 | 62 | ||||||||||

| Procedure Performed by Selective Shunter Surgeon | 60.9 | 215 | 353 | 98.3 | 116 | 118 | 21.4 | 37 | 173 | 100.0 | 62 | 62 | 0.001 |

| Procedure Performed by Routine Shunter Surgeon | 39.1 | 138 | 353 | 0.8 | 1 | 118 | 78.6 | 136 | 173 | 0.0 | 0 | 62 | |

| Technical Aspects of CEA | 118 | 173 | 62 | ||||||||||

| Eversion endarterectomy | 9.7 | 34 | 353 | 20.5 | 24 | 118 | 1.2 | 2 | 173 | 12.9 | 8 | 62 | 0.001 |

| Patch angioplasty | 84.4 | 298 | 353 | 71.2 | 84 | 118 | 95.4 | 165 | 173 | 79.0 | 49 | 62 | 0.001 |

| Protamine | 43.5 | 153 | 353 | 24.6 | 29 | 118 | 61.3 | 106 | 173 | 29.5 | 18 | 62 | 0.001 |

| Completion study | 36.8 | 130 | 353 | 34.8 | 41 | 118 | 39.9 | 69 | 173 | 32.3 | 20 | 62 | 0.479 |

Rate of 30-day stroke or death

The rate of 30-day stroke or death was higher in patients in the setting of a CCO than in those patients who underwent CEA without CCO ( 4.0% versus 1.9%, p<0.007, Table 2). Across the 353 patients undergoing CEA in the setting of a CCO, 14 strokes and 3 deaths occurred within the first 30 days following surgery. All three deaths occurred in patients who had experienced a post-operative stroke. Among 5,279 patients undergoing CEA who did not have a CCO, 100 strokes and 9 deaths occurred, and all but 3 deaths were stroke-related.

Table 2.

Rate of 30-day Stroke or Death, Overall, by CCO status, and by shunt type

| CEA with Contralateral Carotid Occlusion (n=353) | CEA without Contralateral Carotid Occlusion (n=5,279) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % of Total | number with characteristic | Total N | % of Total | number with characteristic | Total N | P-value (CCO vs no CCO)* |

| 30-Day Stroke | 3.97 | 14 | 353 | 1.78 | 100 | 5,279 | 0.002 |

| 30-Day Death | 0.77 | 3 | 353 | 0.1 | 9 | 5,279 | 0.471 |

| 30-Day Stroke or Death | 3.97 | 14 | 353 | 1.93 | 102 | 5,279 | 0.007 |

| CEA with Contralateral Carotid Occlusion (n=353) | CEA without Contralateral Carotid Occlusion (n=5,279) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No Shunt Used n/total (%)* | Routinely Placed Shunt Used n/total (%)* | Shunt Placed For Indication n/total (%)* | P-value (within CCO)* | No Shunt Used n/total (%)* | Routinely Placed Shunt Used n/total (%)* | Shunt Placed For Indication n/total (%)* | P-value (within non-CCO)* |

| 30-Day Stroke | 4 / 118 (3.3%) | 7/ 173 (4.0%) | “3/62” (4.8%) | 0.883 | 46 / 2824 (1.6%) | 41/ 2210 (1.8%) | “9 / 245”(3.7%) | 0.016 |

| 30-Day Death | 1 / 118 (0.1%) | 1 / 173 (0.1%) | “1/62” (0.1%) | 0.759 | “12/2824” (0.1%) | “7/2210” (0.1%) | “2/245” (0.1%) | 0.511 |

| 30-Day Stroke/Death | 4 / 118 (3.4%) | 7 / 173 (4.0%) | 3/62 (4.8%) | 0.883 | 48/2824 (1.7%) | 44/2210 (1.9%) | 10/245 (4.1%) | 0.032 |

P-value from Fisher's Exact Test

P-value from Fisher's Exact Test

Rate of 30-day stroke or death, by shunt use

Within the patients with CCO, there were no significant differences in rates of 30-day stroke or death across categories of shunt use (no shunt 3.4%, routine shunt 4.1%, shunt for indication 4.8%, p=0.8, Table 2). Patient characteristics between the three categories of shunt use did not vary significantly, and therefore the predicted 30-day stroke/death rate risk across the three groups was not different (no shunt, routine shunt, and shunt for indication: 3.4% versus 4.0% versus 4.3%, p=0.891). The O/E ratios were similar across categories of shunt use ( O/E ratios: no shunt = 1.0 (95% CI 0.3-2.4), routine shunt = 1.0 (95% CI 0.4-2.4), shunt for indication 1.1 (95% CI 0.3-3.0)), indicating that when we adjusted for patient characteristics, there were no significant differences in 30-day stroke or death across categories of shunt use.

For comparison, rates of 30 day stroke or death across categories of shunt in patients without CCO are shown in Table 2. This demonstrates that the risk of 30-day stroke or death is significantly higher in patients in whom a shunt is placed for an indication, as compared to routinely placed shunt or patients in whom shunts were not placed (shunt for indication 4.1%, routinely placed shunt 1.9%, no shunt 1.7%, p=0.03).

Rate of 30-day stroke or death, by surgeon practice pattern in shunt use

As shown in Figure 2, 46 of the 74 surgeons in our dataset placed shunts selectively. Selective surgeons performed 62 % of all CEAs in our dataset, including 215 of the 353 (61%) CEAs with CCOs in our study. Nearly all of these “selective” surgeons (40 of the 46, 87%) used a shunt in fewer than 30% of their CEAs. Conversely, 28 surgeons routinely shunted, and these surgeons performed 38 % of all CEAs in our data, including 137 of the 353 (39%) CEAs with CCO in our study.

Surgeons who routinely used shunts in all their CEAs had a significantly lower 30-day stroke or death rate in patients with CCOs (1.5% for surgeons who shunt routinely, 5.6% in surgeons who shunt selectively, p=0.05) (Table 3). This difference was unlikely to be secondary to differences in patient characteristics between the two cohorts, as predicted risks based on patient characteristics were similar between these groups (3.9% versus 3.9%, p=0.961), because patient characteristics associated with stroke or death were similar in both groups (Table 4). We found that the O/E ratio was higher than 1 in patients undergoing selective shunting (O/E ratio = 1.4, 95% CI 1.1-1.7), indicating higher than expected stroke risk,. However, the O/E ratio was lower than 1 for surgeons who placed shunts routinely (O/E ratio = 0.4, 95% CI 0.2-0.9), indicating lower than expected risk of stroke or death, based on pre-operative patient characteristics.

Table 3.

Rate of 30-day Stroke or Death, by CCO status and surgeon practice pattern

| Patients Undergoing CEA in the Setting of a CCO (N=353) | Patients Undergoing CEA in Without a CCO (N=5,279) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Surgeon Shunts Routinely n/total (%)* | Surgeon Shunts Selectively n/total (%)* | p value | Surgeon Shunts Routinely n/total (%)* | Surgeon Shunts Selectively n/total (%)* | p value |

| 30-Day Stroke | 2 /138 | 12 / 215 | 0.027 | “35/1992” | “64/3287” | 0.471 |

| 30-Day Death | 1 / 138 | 2 / 215 | 0.443 | “2/1992” | “4/3287” | 0.636 |

| 30-Day Stroke/Death | 2 /138 (1.5%) | 12 / 215 (5.6%) | 0.054 | 36/1992 (1.81%) | 66/3287 (2.02%) | 0.587 |

** P-value from Fisher's Exact Test

Table 4.

Incidence of risk factors for 30-day stroke or death, by surgeon practice pattern

| Surgeon Shunts Selectively | Surgeon Shunts Routinely | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Over 80 | 14.9% | 11.7% | 0.494 |

| Aspirin or Plavix Use | 87.0% | 91.0% | 0.182 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 7.5% | 8.8% | 0.665 |

| Urgent Procedeure | 10.2% | 13.9% | 0.3 |

| Cortical Ipsilateral Symptoms | 7.4% | 5.1% | 0.688 |

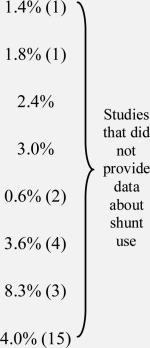

Finally, we examined the rate of 30-day stroke or death, by shunt use and surgeon practice pattern (Figure 3). Surgeons classified as “routine” shunters had the lowest overall rate of 30-day stroke or death when they placed a shunt (1.5%, Figure 3). Surgeons classified as “selective” shunters had a rate of 30-day stroke or death of 3.4% when they chose not to place a shunt in patients with CCO. The rate of 30-day stroke or death was highest for selective surgeons who chose to place a shunt during a CEA with CCO (7.6%). As with our previous results, these differences are not likely to be due to differences in patient characteristics, as predicted risks of 30-day stroke or death did not vary significantly across groups (4.0%, 3.4%, 4.3% respectively, Figure 3). When we calculated O/E ratios, we found that “routine” surgeons who shunted routinely performed slightly better than expected (O/E ratio=0.4, 95% CI 0.2-0.8), “selective” surgeons who did not shunt performed as expected (O/E ratio=0.9, 95% CI 0.7-1.2), and “selective” surgeons who placed a shunt performed slightly worse than expected (O/E ratio=1.7, 95% CI 1.2-2.1) (p trend across O/E ratios = 0.05).

Figure 3.

30-day stroke and death rate in patients with a CCO, by shunt type and surgeon practice pattern

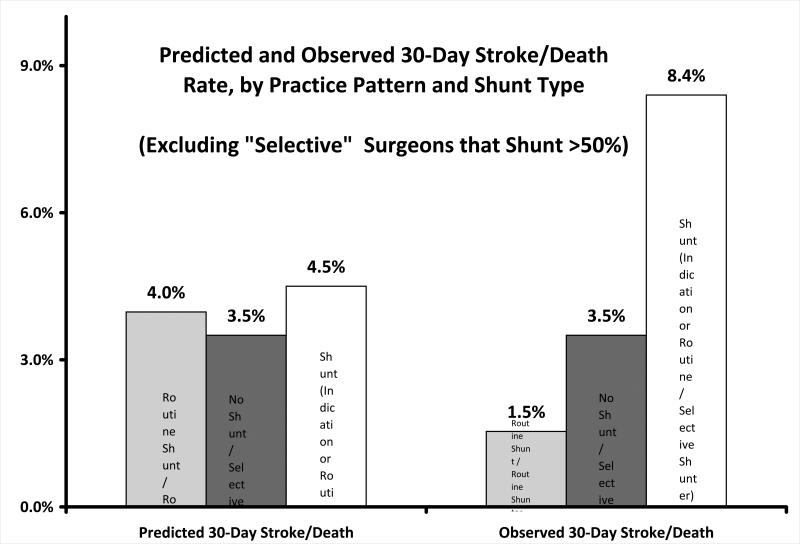

Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis around our definition of “selective” shunt placement (95% of all CEAs) to examine if our findings were due to adverse events occurring in selective surgeons who placed a shunt frequently, such as in 30%, 50% or 90% of their CEAs. As shown in Appendix 1, our results did not change if we eliminated from the analysis any CEA in the setting of a CCO wherein a “selective” surgeon who placed a shunt in more than 30%, 50%, or 90% of their non-CCO cases. This finding reflects the fact that most patients that underwent surgery in the setting of a CCO had surgery performed by surgeons who clustered at the lower (<30%) and higher (>95%) ends of practice patterns. Only 11 CEAs with CCO (3% of the total) were performed by surgeons who shunted in between 30% and 95% of their cases, and none of these patients experienced post-operative stroke or death.

Appendix 1.

30-day stroke and death rate in patients with a CCO, by shunt type and surgeon practice pattern, excluding selective surgeons who shunt >50% of patients . Findings were similar fodr 30% and 90% cutpoints.

Discussion

Within our series of 353 primary CEAs performed in patients with CCO, we found that the risk of 30-day stroke or death was higher in patients with CCO than in patients without CCO. Further, our data indicate that surgeons who placed shunts routinely had low rates of 30-day stroke or death when they placed a shunt, and surgeons who did not routinely use a shunt and performed CEA in the setting of CCO without a shunt also had low rates of 30-day stroke or death, but only when they did not place a shunt. The highest risk-adjusted chance of stroke or death occurred when surgeons who did not typically utilize a shunt placed a shunt during CEA in the setting of a CCO. Therefore, surgeons should consider their own practice pattern in shunt utilization pre-operatively when faced with a patient who may require shunt placement.

The marginal risk imparted in CEA when the contralateral carotid is occluded has long been a topic of debate among vascular surgeons. Secondary data analyses from both the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET)16,17 and the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS)18 demonstrated increased rates of stroke or death among patient with CCO undergoing CEA. However, in 2007, Dalainas et al studied 2,959 CEAs, 373 of which were performed in patients with CCO, and found no significant difference in peri-operative stroke or death between patients with and without CCO19. A similar sized study performed by Rockman et al in 2002, also found similar rates of peri-operative stroke or death between patients with and without CCO14,15. As summarized in Table 5a, most studies have found little difference in outcomes following CEA among patients with CCO.

Table 5a.

Outcomes between CEA patients with and without contralateral carotid occlusion, in the presence or absence of a shunt.

| Stroke/Death rate in CCO (N) |

Stroke/Death rate in non-CCO (N) |

Comparison of 30d stroke/death b/w CCO and non-CCOa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | # of CCO cases | % CCO cases using shunt (N) | Shunt | No Shunt | Comparison of 30d stroke/death (shunt vs. no shunt) | # non-CCO cases | % non-CCO cases using shunt (N) | Shunt | No Shunt | |

| Locatic,24 (2000) | 198 | 83.3% (165) | 4.2% (7) | 3.0% (1) | NS | 1068 | 8.9% (96) | 2.3% (25) | NS | |

| Ballottad,13 (2002) | 68 | 52.9% (36) | 0 | 6.3% (2) | NS | 268 | 4.8% (13) | 23.1% (3) | 0 | NSb |

| Schneiderd,25 (2002) | 57 | 55% (31) | 0 | 0 | NS | 507 | 13% (66) | 7.6% (5) | 0 | NSb |

| Cinar9 (2004) | 55 | 10.9% (6) | 50% (3) | 0 | <0.001 | 374 | 9.1% (34) | 8.8% (3) | 0.9% (3) | NSb |

| Ballotta26 (2004) | 135 | 54% (73) | 0 | 4.8% (3) | NS | 38 | 15.7% (6) |

|

NS | |

| Fitzpatrick27 (2005) | 16 | 68.8% (11) | 9.1% (1) | 0 | NS | 154 | 46.7% (72) | NS | ||

| Ballottae, 13 (2002) | 68 | 52.9% (36) |

|

268 | 4.8% (13) | NSb | ||||

| Schneidere, 25 (2002) | 57 | 55% (31) | 507 | 13% (66) | NSb | |||||

| Pulli28 (2002) | 82 | 25.6% (21) | 1242 | 6.9% (86) | NS | |||||

| Rockmand,14,15 (2002, 2004) | 338 | 66.2% (224) | 2082 | 27.3% (568) | NS | |||||

| Rockmane,14,15 (2002, 2004) | 338 | 66.2% (224) | 2082 | 27.3% (568) | NSb | |||||

| Domenig29 (2003) | 112 | 82.1% (92) | 1752 | 76.9% (1348) | NS | |||||

| Bellosta30 (2006) | 36 | 100% | 706 | 100% | <0.001a | |||||

| Dalainas19 (2007) | 373 | 28.7% (107) | 2959 | 7.1% (210) | NS | |||||

Doesn't report . stroke/death rate by shunt use or shunt use was 0% or 100%

Data extracted/combined from original article and assessed by this author using chi2 with Fisher's exact.

Rates reported include TIA, stroke and death.

Complication rates reflect peri-operative stroke only (mortality excluded)

Complication rates reflect peri-operative mortality only (stroke excluded)

The role of shunt placement during CEA is also widely debated. Several prior series and a recently updated meta-analysis of randomized trials found no significant difference in outcomes following CEA among surgeons who routinely shunt and those who selectively shunt20. In the subset of CEAs with CCO, multiple observational studies have also found no impact of shunting on stroke or death following CEA with CCO (Table 5a and 5b).

Table 5b.

Studies that report comparison of selective versus routine shunting or shunt versus no shunt.

| Comparison of Selective vs Routine Shunting | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | # in Selective Shunt (# shunted) | Stroke/Death in Selective Shunt | # in Routine Shunt | Stroke/death rate in routine shunt | P-value for selective vs routine | Stroke/Death in Shunt | Stroke/Death in No Shunt | P-value for shunt vs no shuntb |

| Woodworth31 (2007) | 194 (41) | 1% (2)a | 1217 | 3.9% (47) | 0.04 | 3.8% | 0.7% | 0.047 |

| AbuRahma32 (2010) | 102 (29) | 2% (2) | 98 | 0 | NS | 0% | 2.7% | NS |

| Grga33 (2001) | 144 (43) | 3.5% (5) | 170 | 0.6% (1) | NSb | 0.9% | 4.0% | NS |

| Nguyen34 (2005) | 117 (22) | 0.8% (1) | 878 | 0.7% (6) | NSb | 0.8% | 0 | NS |

| Salvianc,35 (1997) | 213 (34) | 0.5% (1) | 92 | 4.4% (4) | NS | 3.2% | 0.6% | NS |

| Comparison of Shunt vs No Shunt | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | # Shunted | Stroke/Death in Shunted | # Not Shunted | Stroke/Death in Non-Shunted | p-value for shunt vs no shuntb |

| Chang36 (2000) | 4.1% (112) | 2.7% (3) | 95.5% (2612) | 1.1% (28) | NS |

| Ballotta12 (2003) | 43 | 2.3% (1) | 581 | 0.5% (3) | NS |

| Palombo37 (2007) | 50% (48) | 0 | 50% (48) | 0 | NS |

| Ballotta5 (2010) | 16.3% (312) | 3.2% (1)a | 83.7% (1602) | 0.62% (10) | NS |

Complication rates reflect peri-operative stroke only (mortality excluded)

In many cases, data were extracted from original article and assessed by this author using chi2 with Fishers exact tests.

Complication rates reflect peri-operative major stroke only (mortality and minor stroke [resolved within 30days] excluded

Our results demonstrate increased risk of stroke/death exists for CEA performed in the presence of CCO, and found that surgeons who shunt infrequently incur an increased risk of stroke when shunting is performed. While debate regarding the influence of these two covariates (CCO status and shunt use) on stroke/death risk will undoubtedly continue, our study adds to the current debate in two ways.

First, our study represents a large number of patients undergoing CEA with CCO in a “real-world” setting of mixed academic and community practice. Second, our study indicates that surgeons who routinely place shunts during all their CEAs have better results than surgeons who place shunt selectively in the setting of a CCO, a novel observation in carotid surgery. We believe it is plausible that a relationship exists between the routine performance of a technically demanding process of care in surgery, and better outcomes. Relationships such as these have multiple precedents in surgery. For example, the use of LIMA grafts during CABG and routine cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy21,22 are both commonly referenced examples of the association between routine performance of complex processes of care with better surgical outcomes. While indirect, our data suggests that the surgeons who perform shunt placement routinely are those who are most likely to perform it safely. Conversely, if an unplanned shunt is required for a specific indication in a patient with CCO, the infrequent shunt user had a substantially higher stroke/death rate.

Do our results suggest that shunt placement should be always be performed in CEA in the setting of CCO? We believe the answer is no. Rather, we believe our data suggests that the safest operation a surgeon can provide in the setting of a CCO is the operation that the surgeon would perform without the CCO being present. In other words, surgeons who shunt routinely fared best when they routinely placed shunts, and selective surgeons, on average, obtained the best results when they performed CEA in the way they most commonly performed the operation - without a shunt. We believe that surgeons can use our study to inform their decision-making pre-operatively when faced with a patient likely to need a shunt, such as a patient with a CCO and an incomplete circle of Willis. In this setting, selective surgeons may choose to use strategies to limit the need for shunting such as permissive hypertension, or refer the patient to a colleague who places shunts commonly. However, our study is small, and will need to be replicated in larger settings before these conclusions are made.

Our study has limitations. Many will argue that our study, which is observational in nature, cannot fully account for patient differences or intra-operative events that led surgeons who do not usually shunt to place a shunt during high-risk CEA. And while our observational dataset does not obviate bias or confounding as a randomized trial might, our validated multivariable risk model fails to demonstrate any significant differences in patient characteristics that may explain our findings.. Second, our designation of surgeon practice pattern was established using data from surgeon's practice pattern not in the setting of a CCO, and most surgeons designated as “selective” shunters were indeed selective (i.e. shunted infrequently) in the use of this process of care. Many believe that the use of a shunt in 90% of cases more closely represents “routine” utilization. However, we have performed sensitivity analyses examining the impact of different cutpoints, (such as 30%, 50%, 80%, and 90%) and found little difference in the direction or magnitude of effect of our findings. Third, the use of neuro-monitoring differs across surgeons, as some use EEG, others awake CEA, and still others stump pressure as an indicator to place a “shunt for indication.” While we found no systematic evidence that these choices varied dramatically by surgeon practice pattern, the non-randomized nature of this covariate could potentially introduce bias. Lastly, given the non-randomized nature of our dataset, we are unable to infer what might have occurred if a selective surgeon had chosen not to place a shunt during one of the cases wherein they shunted for an indication.

Finally, beyond the debates surrounding the technical points of carotid surgery, all interested parties (surgeons, payers, and patients) all agree that procedure-specific quality measures are needed to most effectively measure and improve performance23. At the outset of this project, it was our hypothesis that shunt use would be associated with better outcomes for CEA in the setting of CCO. It seemed to be a reasonable presumption that shunt use in the setting of CCO could potentially serve as a reasonable procedure-specific quality indicator in vascular surgery. However, as outlined above, our registry data refuted this hypothesis, leading us to conclude that shunt use is not a useful quality measure, because surgeons can achieve excellent outcomes with or without using a shunt. This process illustrates the need for vascular surgeons to become active participants in developing and vetting quality measures, a process that will often require detailed clinical data from representative, real-world practice.

In conclusion, within our multi-center registry, the risk of 30-day stroke was significantly higher in patients with CCO. Further, while shunt use itself was not directly associated with lower rates of 30-day stroke or death, surgeons who use a shunt infrequently during any CEA have higher rates of stroke / death when treating patients with a CCO with a shunt. Our results suggests that shunt use in CEA with CCO is associated with a lower rate stroke/death, but only if the surgeon uses a shunt as part of their routine practice. .

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Goodney was supported by a grant from the Hitchcock Foundation, Hanover NH, and a K08 Award from the NHLBI, and a AVA/ACS Supplemental Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adelman MA, Jacobowitz GR, Riles TS, et al. Carotid endarterectomy in the presence of a contralateral occlusion: a review of 315 cases over a 27-year experience. Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;3:307–12. doi: 10.1016/0967-2109(95)93881-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobowitz GR, Adelman MA, Riles TS, Lamparello PJ, Imparato AM. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy in the presence of a contralateral occlusion. American Journal of Surgery. 1995;170:165–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Julia P, Chemla E, Mercier F, Renaudin JM, Fabiani JN. Influence of the status of the contralateral carotid artery on the outcome of carotid surgery. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 1998;12:566–71. doi: 10.1007/s100169900201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samson RH, Showalter DP, Yunis JP. Routine carotid endarterectomy without a shunt, even in the presence of a contralateral occlusion. Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;6:475–84. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(98)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballotta E, Saladini M, Gruppo M, Mazzalai F, Da Giau G, Baracchini C. Predictors of electroencephalographic changes needing shunting during carotid endarterectomy. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2010;24:1045–52. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bydon A, Thomas AJ, Seyfried D, Malik G. Carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral internal carotid artery occlusion without intraoperative shunting. Surg Neurol. 2002;57:325–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(02)00678-x. discussion 31-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frawley JE, Hicks RG, Gray LJ, Niesche JW. Carotid endarterectomy without a shunt for symptomatic lesions associated with contralateral severe stenosis or occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23:421–7. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(96)80006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimakakos PB, Antoniou A, Papasava M, Mourikis D, Rizos D. Carotid endarterectomy without protective measures in patients with occluded and non occluded contralateral carotid artery. Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery. 1999;40:849–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cinar B, Goksel OS, Karatepe C, et al. Is routine intravascular shunting necessary for carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral occlusion? A review of 5-year experience of carotid endarterectomy with local anaesthesia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;28:494–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronenwett JL, Likosky DS, Russell MT, et al. A regional registry for quality assurance and improvement: the Vascular Study Group of Northern New England (VSGNNE). Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2007;46:1093–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.012. discussion 101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodney PP, Likosky DS, Cronenwett JL. Vascular Study Group of Northern New E. Factors associated with stroke or death after carotid endarterectomy in Northern New England. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2008;48:1139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballotta E, Da Giau G. Selective shunting with eversion carotid endarterectomy. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2003;38:1045–50. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballotta E, Da Giau G, Baracchini C. Carotid endarterectomy contralateral to carotid artery occlusion: analysis from a randomized study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;387:216–21. doi: 10.1007/s00423-002-0312-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rockman C. Carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral carotid occlusion. Seminars in Vascular Surgery. 2004;17:224–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7967(04)00048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rockman CB, Su W, Lamparello PJ, et al. A reassessment of carotid endarterectomy in the face of contralateral carotid occlusion: surgical results in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2002;36:668–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson GG, Eliasziw M, Barr HW, et al. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial : surgical results in 1415 patients. Stroke. 1999;30:1751–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.9.1751. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasecki AP, Eliasziw M, Ferguson GG, Hachinski V, Barnett HJ. Long-term prognosis and effect of endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis and contralateral carotid stenosis or occlusion: results from NASCET. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) Group. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1995;83:778–82. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.5.0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA. 1991;273:1421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalainas I, Nano G, Bianchi P, Casana R, Malacrida G, Tealdi DG. Carotid endarterectomy in patients with contralateral carotid artery occlusion. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bond R, Rerkasem K, Counsell C, et al. Routine or selective carotid artery shunting for carotid endarterectomy (and different methods of monitoring in selective shunting). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002:CD000190. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips EH. Routine versus selective intraoperative cholangiography. American Journal of Surgery. 1993;165:505–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80950-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berci G, Sackier JM, Paz-Partlow M. Routine or selected intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? American Journal of Surgery. 1991;161:355–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90597-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs’ NSQIP: the first national, validated, outcome-based, risk-adjusted, and peer-controlled program for the measurement and enhancement of the quality of surgical care. National VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Annals of Surgery. 1998;228:491–507. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Locati P, Socrate AM, Lanza G, Tori A, Costantini S. Carotid endarterectomy in an awake patient with contralateral carotid occlusion: influence of selective shunting. Ann Vasc Surg. 2000;14:457–62. doi: 10.1007/s100169910081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider JR, Droste JS, Schindler N, Golan JF, Bernstein LP, Rosenberg RS. Carotid endarterectomy with routine electroencephalography and selective shunting: Influence of contralateral internal carotid artery occlusion and utility in prevention of perioperative strokes. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1114–22. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.124376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballotta E, Renon L, Da Giau G, Barbon B, Terranova O, Baracchini C. Octogenarians with contralateral carotid artery occlusion: a cohort at higher risk for carotid endarterectomy? J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:1003–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzpatrick CM, Chiou AC, DeCaprio JD, Kashyap VS. Carotid revascularization in the presence of contralateral carotid artery occlusion is safe and durable. Mil Med. 2005;170:1069–74. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.12.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pulli R, Dorigo W, Barbanti E, et al. Carotid endarterectomy with contralateral carotid artery occlusion: is this a higher risk subgroup? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;24:63–8. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domenig C, Hamdan AD, Belfield AK, et al. Recurrent stenosis and contralateral occlusion: high-risk situations in carotid endarterectomy? Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2003;17:622–8. doi: 10.1007/s10016-003-0068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellosta R, Luzzani L, Carugati C, Talarico M, Sarcina A. Routine shunting is a safe and reliable method of cerebral protection during carotid endarterectomy. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2006;20:482–7. doi: 10.1007/s10016-006-9037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodworth GF, McGirt MJ, Than KD, Huang J, Perler BA, Tamargo RJ. Selective versus routine intraoperative shunting during carotid endarterectomy: a multivariate outcome analysis. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:1170–6. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000306094.15270.40. discussion 6-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aburahma AF, Stone PA, Hass SM, et al. Prospective randomized trial of routine versus selective shunting in carotid endarterectomy based on stump pressure. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2010;51:1133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grga A, Hebrang A, Brkljacic B, Hlevnjak D, Sarlija M. Asymptomatic carotid stenosis: selective or routine use of intraluminal shunt. Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery. 2001;42:657–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen TQ, Lind L, Harris EJ., Jr Selective shunting during carotid endarterectomy. Vascular. 2005;13:23–7. doi: 10.1258/rsmvasc.13.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salvian AJ, Taylor DC, Hsiang YN, et al. Selective shunting with EEG monitoring is safer than routine shunting for carotid endarterectomy. Cardiovascular Surgery. 1997;5:481–5. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(97)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang BB, Darling RC, 3rd, Patel M, et al. Use of shunts with eversion carotid endarterectomy. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2000;32:655–62. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.110171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palombo D, Lucertini G, Mambrini S, Zettin M. Subtle cerebral damage after shunting vs non shunting during carotid endarterectomy. European Journal of Vascular & Endovascular Surgery. 2007;34:546–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]