Summary

Targeted therapies against somatically altered genes are currently used for the treatment of many human cancers. The nascent technology, BEAMing, has potential to increase the clinical utility of these agents as it allows for the detection of cancer mutations in peripheral blood, providing a rapid assessment of tumor mutation status.

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, Taniguchi et al. use a novel technology called BEAMing to query for a common second site EGFR mutation (T790M) that confers resistance to small molecule EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer patients, using blood as the source for mutant DNA detection (1). As background, somatically mutated or altered genes have led to effective targeted therapies and improved biomarkers for clinical decision making. As the use of these targeted therapies becomes more widespread, a great unmet need has arisen for companion diagnostic technologies that can reliably and quickly identify patients with cancers that harbor the mutation/genetic alteration to be targeted. Of particular challenge, the ascertainment of mutational status in solid tumors has often depended on biopsies of metastatic sites, followed by conventional genotyping assays with limited sensitivity. Such biopsies can be difficult to obtain, even in a research setting, resulting in a great impetus for developing sensitive, non-invasive diagnostic tools to assay for the mutational status of a tumor and molecular predictors of response.

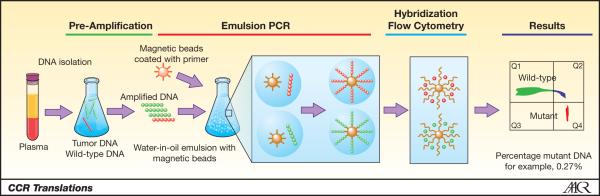

BEAMing (Beads, Emulsification, Amplification, and Magnetics) is one such technology, and relies on single molecule PCR at a massively parallel scale, similar to next-generation DNA sequencing technologies (2, 3) (Figure 1). The mechanics of BEAMing start with amplification of a pre-determined locus of interest using conventional PCR. Next the PCR product is added to hundreds of thousands of oligonucleotide-coupled beads in oil, and an emulsion is created such that most of the beads will bind only a single DNA molecule. A second round of PCR is then performed. After de-emulsification and magnetic capture, single-base primer extension, or hybridization with mutant specific probes, is performed using different fluorescently labeled nucleotides for either wild type or mutant sequences. Finally, flow cytometric analysis of hundreds of thousands of beads allows for the detection and quantification of wild type or mutant alleles. Because BEAMing is a “digital” PCR technique analyzing one allele at a time, it is highly sensitive for the detection of rare mutant alleles within a large population of wild type alleles. This is the exact molecular environment found in circulating plasma of cancer patients, i.e. rare circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) intermixed amongst a vast pool of non-cancerous DNA.

Figure 1. Principles of BEAMing.

Shown are the sequential steps involved with BEAMing. Results are expressed as a ratio of mutant to wild type DNA molecules using flow cytometry providing a quantitative measurement of mutant DNA present in the plasma. Figure adapted with permission from Inostics.

Taniguchi et al. have applied the BEAMing technology for the first time to the analysis of EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (1). Activating mutations in EGFR are found in approximately 10% of Caucasian non-small cell lung cancer cases and up to 50% of Asian cases, and are enriched in females, never-smokers, and adenocarcinomas. Such patients are now routinely offered therapy with small molecule EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKI), gefitinib or erlotinib. Unfortunately, resistance to these agents universally occurs. In 50% of cases, resistance is associated with the emergence of a second-site “gatekeeper” mutation in EGFR, T790M (4, 5). The authors studied two cohorts of patients with stage III or IV non-small cell lung cancer who had activating EGFR mutations found in their diagnostic biopsy specimens. Cohort 1 had progressive disease after treatment with an EGFR-TKI, and cohort 2 had never received an EGFR-TKI. Overall, BEAMing had a sensitivity of 72.7% in detecting the known activating EGFR mutation in plasma ctDNA collected at a single time point. In the progressive disease cohort a T790M resistance mutation was identified in 43.5% of patients, a value near the predicted 50%. This is the first use of BEAMing to detect a drug resistance mutation, although other technologies have been used for this purpose in past studies (6-9). Because BEAMing is both qualitative and quantitative, Taniguchi et al. were able to calculate the ratio of T790M mutations to the original activating EGFR mutations for each patient, with ratios ranging from 13.3 to 94%. One would predict that when this ratio reaches 100%, all of the cancer cells with activating EGFR mutations will also have acquired T790M resistance mutations—or alternatively, the T790M containing cells outgrew or out-survived the cells without T790M mutations. Preclinical data has shown that T790M cells are outcompeted for growth by T790T cells in the absence of selective pressure from EGFR-TKI’s (10). Thus the ratio of resistance to activating mutations may provide a measure of the clonal dominance of the tumor subclones with resistance mutations.

Studies such as that of Taniguchi et al. are important steps in the application of new genotyping technologies to clinical cancer care. However, there are some notable limitations and caveats. As the authors note, theirs was not a prospective study, and they did not analyze plasma ctDNA at serial time points. It is not known whether any of the patients who had T790M resistance mutations after EGFR-TKI treatment harbored such mutations at low levels in their primary tumors before treatment, which has been previously described (11, 12). To address this, future studies could also use BEAMing on the primary tumor biopsy or surgical specimen as its high sensitivity would theoretically be able to detect this presumably minute drug resistant population. This would give a clearer picture of the potential pre-existing tumor heterogeneity that may be below the current level of detection with conventional techniques, and may also give insight into the sensitivity of BEAMing ctDNA for detecting microscopic amounts of tumor. If, for example, a T790M population of cancer cells was present at less than 1% in the primary tumor at the time of diagnosis/surgery, could BEAMing of plasma detect this minority population?

Other potential applications of BEAMing include non-invasive diagnosis, screening, and detection of micrometastatic disease post-operatively to aid decisions regarding the need for adjuvant systemic therapies. However, many questions need to be answered in further depth and detail. This will require numerous studies involving large populations of patients across different tumor types, treated with a full range of therapies. In addition, such studies will also necessitate the analysis of BEAMing using serial time points to better elucidate the factors that influence the generation and stability of ctDNA and to fully understand the sensitivity and specificity of BEAMing as related to a given tumor type and response to specific classes of therapies. Other questions will also arise; for example it is currently unclear if a low level of detectable ctDNA in plasma has clinical meaning or usefulness. In a small number of colon cancer patients studied retrospectively, detectable mutant DNA predicted eventual overt disease progression, but clearly more studies are needed (13). Likewise, in the study by Taniguchi et al., T790M resistance mutations were found in patients with progressive disease, but we do not know at what quantitative level such mutations predict clinical failure of EGFR-TKI therapy.

Thus, perhaps the most powerful utility of BEAMing is the ability to quantitate the amount of cancer specific ctDNA. BEAMing could potentially assess tumor burden and tumor heterogeneity with great sensitivity and address important questions with greater precision. Is a patient with no detectable ctDNA after surgery cured? Can we rapidly ascertain whether a patient is benefitting from a chosen therapy? Does early detection of resistance mutations allow for meaningful therapeutic interventions? These questions will undoubtedly be answered as BEAMing and other technologies mature. Ultimately, the ability to detect microscopic amounts of tumor burden will better inform clinicians and patients, and allow for a tailored approach for the treatment of human cancers.

References

- 1.Taniguchi K, Uchida J, Nishino K, et al. Quantitative detection of EGFR mutations in circulating tumor DNA derived from lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dressman D, Yan H, Traverso G, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Transforming single DNA molecules into fluorescent magnetic particles for detection and enumeration of genetic variations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8817–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133470100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diehl F, Li M, He Y, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Dressman D. BEAMing: single-molecule PCR on microparticles in water-in-oil emulsions. Nat Methods. 2006;3:551–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maheswaran S, Sequist LV, Nagrath S, et al. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:366–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Janne PA, Makrigiorgos GM. Biotinylated probe isolation of targeted gene region improves detection of T790M epidermal growth factor receptor mutation via peptide nucleic acid-enriched real-time PCR. Clin Chem. 2011;57:770–3. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.157784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura T, Sueoka-Aragane N, Iwanaga K, et al. A noninvasive system for monitoring resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors with plasma DNA. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1639–48. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822956e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuang Y, Rogers A, Yeap BY, et al. Noninvasive detection of EGFR T790M in gefitinib or erlotinib resistant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2630–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chmielecki J, Foo J, Oxnard GR, et al. Optimization of dosing for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer with evolutionary cancer modeling. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:90ra59. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell DW, Gore I, Okimoto RA, et al. Inherited susceptibility to lung cancer may be associated with the T790M drug resistance mutation in EGFR. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1315–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inukai M, Toyooka S, Ito S, et al. Presence of epidermal growth factor receptor gene T790M mutation as a minor clone in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7854–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med. 2008;14:985–90. doi: 10.1038/nm.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]