Abstract

The authors report a case of atypical extraventricular neurocytoma (EVN) transformed from EVN which had been initially diagnosed as an oligodendroglioma 15 years ago. An 8-year-old boy underwent a surgical resection for a right frontal mass which was initially diagnosed as oligodendroglioma. When the tumor recurred 15 years later, a secondary operation was performed, followed by salvage gamma knife treatment. The recurrent tumor was diagnosed as an atypical EVN. The initial specimen was reviewed and immunohistochemistry revealed a strong positivity for synaptophysin. The diagnosis of the initial tumor was revised as an EVN. The patient maintained a stable disease state for 15 years after the first operation, and was followed up for one year without any complications or disease progression after the second operation. We diagnosed an atypical extraventricular neurocytoma transformed from EVN which had been initially diagnosed as an oligodendroglioma 15 years earlier. We emphasize that EVN should be included in the differential diagnosis of oligodendroglioma.

Keywords: Atypical extraventricular neurocytoma, Differential diagnosis, Oligodendroglioma, Recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Parenchymal neurocytoma remote from the ventricle, called "extraventricular neurocytoma (EVN)," was reported in 199219). It shares similar biological behaviors and histopathological characteristics with central neurocytoma. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of brain tumors revised in 2007 includes EVN as a single pathological diagnosis and proposes an ICD-O code identical to that of central neurocytoma8). The neurocytoma, which exhibited a MIb-1 labeling index of >2%, or atypical histological features, increased mitosis, focal necrosis and vascular proliferation, was classified as atypical2,18) Some of these cases could have been misdiagnosed as oligodendrogliomas due to similarities of clinical and histological features and the relative imprecision of neuroradiological diagnostic tools available at that time. Here, we report a case of atypical EVN that was diagnosed and treated as oligodendroglioma in 1993.

CASE REPORT

An 8-year-old boy with convulsive seizure attack was admitted to our hospital in 1993. At that time, he had one year history of headache. No focal neurologic deficit was found on admission. Brain computed tomography scans revealed a high-density mass in the frontal lobe with midline shifting. Magnetic resonance (MR) images showed a heterogeneous enhancing mass in the frontal lobe apart from the lateral ventricle. The mass was yellow and friable. It was neither hemorrhagic nor necrotic. The tumor margin was ill-defined. Immumohistochemistry for neurone specific enolase and chromogranin was negative. The initial diagnosis of the tumor was oligodendroglioma. He was discharged from the hospital without neurologic deficits or additional treatment. The patient was followed yearly with brain MR imaging. During the follow up periods, the mass had showed no specific changes and the patient had done well without any neurologic deterioration.

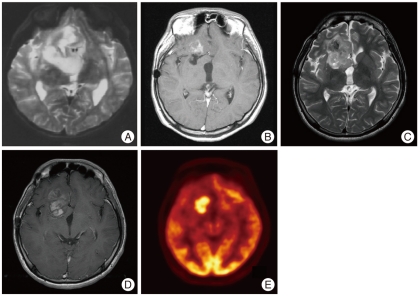

The MR images taken 15 years after the initial surgery showed a solid enhancing lesion of high signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images and low signal intensity on T1-weighted MR images in the right frontal area. The new lesion was thought to be a recurrent tumor with malignant transformation (Fig. 1) because MR spectroscopy image of the lesion showed the elevation of choline and lactate peaks, the inversion of a lactate peak at long TE sequence and a decrease in N-acetyl aspartate. 18F-FDG positron emission tomography images showed that the mass was hypermetabolic in its inferior portion. A second operation was performed and a hard calcified mass with a yellow and friable cystic portion was found. The mass was subtotally removed as the attachment sites to the internal capsule and basal ganglia were left alone.

Fig. 1.

A : Preoperative T2-weighted image from the surgical specimen at the first operation demonstrates heterogeneous signal intensity in a right frontal mass. B : Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image shows subtle peripheral enhancement 13 years after the first operation. C : T2-weighted image taken 15 years after the first operation demonstrates high signal intensity mass lesion in the right frontal lobe. D : Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image taken 15 years after the first operation shows marked enhancement. E : 18F-FDG brain positron emission tomography shows a hypermetabolic lesion in the right inferior frontal lobe.

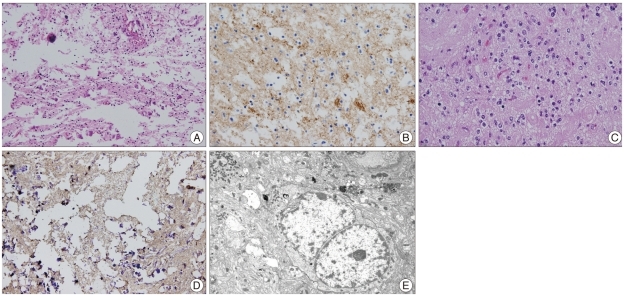

Pathologic examination revealed mitosis in 2 of 10 high power fields and electron microscopy of the ultrathin sections showed round to oval neoplastic cells. Tumor cell nuclei were relatively uniform with marginated chromatin, and cytoplasmic organelles were sparse and include a few strands of rough endoplasmic reticulum cisternae, dense bodies and glycogen particles. There were abundant cell processes containing neurosecretory-type dense granules, microtubules and glycogen particles with well developed synapses with accompanying synaptic vesicles (Fig. 2). Fluorescence in situ hybridization showed that chromosomes 1p and 19q were intact. Immunohistochemistry revealed a high Ki-67 labeling index of 16.8%. The pathologic result was consistent with atypical extraventricular neurocytoma. To confirm the previous pathologic diagnosis, we reexamined the specimen taken from the first operation. Immunohistochemistry revealed a strong immunoreactivity for synaptophysin which was consistent with EVN.

Fig. 2.

A : H&E staining shows round to oval, small uniform cells from the specimen taken at the first operation (Magnification; ×200, H&E stain). B : Immunostaining for synaptophysin demonstrates a strong positivity in the specimen taken at the first operation (Magnification; ×400, synaptophysin immunochemical stain). C : Small round cells with large clear cytoplasms and round nuclei (Magnification; ×400, H&E stain). D : A strong positivity for synaptophysin is seen (Magnification; ×400, synaptophysin immunochemical stain). E : Electron microscope shows that the cytoplasmic organelles are sparse and include a few strands of RER cisternae, dense bodies and glycogen particles (Magnification; ×7,000, electron microscopy).

The patient recovered without any neurologic deficits after surgery. Followed-up MR images showed residual tumor in the right frontal lobe, which was treated with gamma knife. Follow-up brain MR images taken at 12 months after gamma knife radiosurgery showed no further growth of the residual tumor and the patient lived well without any adverse effect.

DISCUSSION

EVN is a tumor of the central nervous system that rarely occurs in young people. This tumor is usually located in the periventricular parenchyma with benign nature. In 1997, Giangaspero et al.2) reported the first case of a tumor that mimicked central neurocytoma but was located in the extraventricular area. The 2007 WHO classification included EVN as a brain tumor entity to distinguish it from intraventricular neurocytoma8). It is a diagnostic challenge to differentiate oligodendroglioma from EVN because of its similarities in clinical and histological findings2,3). Sgouros et al.17) have shown that tumors previously diagnosed as oligodendroglioma can be reclassified as central neurocytomas, a new entity. Perry et al.13) have suggested a potential histogenic link between oligodendroglioma and EVN. EVN and oligodendroglioma share common histological features such as round, regular nuclei with clear cytoplasms, although ganglionic differentiation is more common in EVN. Immunochemistry is needed to differentiate EVN from oligodendroglioma. EVN shows a strong immunoreactivity for synaptophysin in the neuropil and perinuclear cytoplasm, whereas oligodendroglioma usually shows negative reactions. Perry et al.12) reported that chromosome 1p loss occurs in 40-92% of the tumor, and 19q loss in 50-80%. Loss of chromosome 1p/19q has not been detected in EVN, which provides a clue to differentiate it from oligodendrogliomas. Fujisawa et al.4) mentioned that allelic loss on 1p and 19q can be useful for making a differential diagnosis. In our case, the patient was first diagnosed with a oligodendroglioma by light microscopic examination and underwent subtotal resection without additional treatment. He survived for 15 years without neurological deficits and maintained a stable disease state without adjuvant therapy. Follow-up MR imaging showed a recurrent tumor just beside the pre-existing residual mass in the right frontal area. Because histological findings were consistent with atypical EVN, immunohistochemistry was performed, which revealed a strong immunoreactivity for synaptophysin, being consistent with EVN. It is thought that the differential diagnosis between EVN and oligodendroglioma was not established and the tumor resected in 1993 under a misdiagnosis of oligodendroglioma. We concluded that the tumor was actually EVN and the residual mass underwent malignant transformation to atypical EVN after 15 years. Sakurada et al.16) reported a case of EVN that was initially diagnosed as oligodendroglioma but was later diagnosed as EVN from the surgical specimen taken at the second operation for the tumor which recurred 25 years later. When the surgical specimen taken at the first operation was reexamined, the specimen was consistent with EVN. Although his patient survived for 25 years, she died 4 months after the second operation. In our case, the patient maintained a stable disease state for 15 years after the first operation, and was followed up for 1 year without any complications and disease progression after the second operation. The neurocytoma, which exhibited a MIb-1 labeling index of >2%, or atypical histological features, increased mitosis, focal necrosis and vascular proliferation, was classified as atypical2,18). This is the first reported case of an EVN with malignant transformation into atypical EVN. The initial diagnosis of oligodendroglioma was made without immunochemistry which may have been helpful in differentiating between oligodendroglioma and EVN. Therefore, immunohistochemisty should be performed in cases which require differential diagnosis of these two entities.

The treatment of atypical neurocytoma is not well established. Rades et al.14) have documented that complete resection would provide better local control and survival rates than incomplete resection and that local control and survival rates are improved with postoperative radiation therapy in cases of incomplete resection. Since there have been only a few reports on the outcomes of chemotherapy in patients with atypical neurocytoma1), the therapeutic effect of chemotherapy remains uncertain. In our case, complete resection was not performed because of the possibility of injury to the basal ganglia and internal capsule. To obtain a better local control and a higher survival rate, additional gamma knife (GK) stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) was performed. Although central neurocytoma (CN) has benign biological behavior, conventional radiotherapy has been effective to control residual CN after surgery7,11). However, Some authors criticized conventional radiotherapy could induce delayed complication5,9,10). Rades and Schild15) reported the outcome of CN after incomplete resection followed by conventional radiotherapy or GK SRS. They concluded that the GK SRS could be the alternative treatment option for the residual CN. Kim et al.6) reported the long-term outcome of GK SRS with CN. They treated CN with GK SRS as a primary or a secondary postoperative therapy. The GK SRS could be a primary or secondary postoperative treatment, and especially, it could be a initial treatment for the CN in a small size mass that the longitudinal diameter was below 3 cm. EVN has the same pathologic feature with CN, so GK SRS could be a attractive treatment option of EVN in a small size.

CONCLUSION

EVN is a benign tumor that is difficult to diagnose because it shares common clinical and histologic features with oligodendroglioma. There is the possibility that EVN was misdiagnosed in the past as oligodendroglioma because diagnostic tools were underdeveloped and the disease entity of EVN was not clearly established. Since these two tumors have different prognoses and treatment outcomes, their differential diagnosis is very important to establish an appropriate treatment plan. Immunochemisty plays an important role in the differential diagnosis between EVN and oligodendroglioma.

References

- 1.Brandes AA, Amistà P, Gardiman M, Volpin L, Danieli D, Guglielmi B, et al. Chemotherapy in patients with recurrent and progressive central neurocytoma. Cancer. 2000;88:169–174. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000101)88:1<169::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brat DJ, Scheithauer BW, Eberhart CG, Burger PC. Extraventricular neurocytomas : pathologic features and clinical outcome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1252–1260. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi YS, Song YJ, Huh KY, Kim KU. Malignant variant of the central neurocytoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2004;35:313–316. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujisawa H, Marukawa K, Hasegawa M, Tohma Y, Hayashi Y, Uchiyama N, et al. Genetic differences between neurocytoma and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor and oligodendroglial tumors. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:1350–1355. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.6.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton R. Case of the month. August 1996--frontal lobe tumor in 11 year old girl. Brain Pathol. 1997;7:713–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1997.tb01086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CY, Paek SH, Jeong SS, Chung HT, Han JH, Park CK, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for central neurocytoma : primary and secondary treatment. Cancer. 2007;110:2276–2284. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim DG, Paek SH, Kim IH, Chi JG, Jung HW, Han DH, et al. Central neurocytoma : the role of radiation therapy and long term outcome. Cancer. 1997;79:1995–2002. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970515)79:10<1995::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maiuri F, Spaziante R, De Caro ML, Cappabianca P, Giamundo A, Iaconetta G. Central neurocytoma : clinico-pathological study of 5 cases and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1995;97:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(95)00031-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namiki J, Nakatsukasa M, Murase I, Yamazaki K. Central neurocytoma presenting with intratumoral hemorrhage 15 years after initial treatment by partial removal and irradiation. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1998;38:278–282. doi: 10.2176/nmc.38.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paek SH, Han JH, Kim JW, Park CK, Jung HW, Park SH, et al. Long-term outcome of conventional radiation therapy for central neurocytoma. J Neurooncol. 2008;90:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry A, Fuller CE, Banerjee R, Brat DJ, Scheithauer BW. Ancillary FISH analysis for 1p and 19q status : preliminary observations in 287 gliomas and oligodendroglioma mimics. Front Biosci. 2003;8:a1–a9. doi: 10.2741/896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry A, Scheithauer BW, Macaulay RJ, Raffel C, Roth KA, Kros JM. Oligodendrogliomas with neurocytic differentiation. A report of 4 cases with diagnostic and histogenetic implications. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:947–955. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.11.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rades D, Fehlauer F, Schild SE. Treatment of atypical neurocytomas. Cancer. 2004;100:814–817. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rades D, Schild SE. Value of postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery and conventional radiotherapy for incompletely resected typical neurocytomas. Cancer. 2006;106:1140–1143. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakurada K, Akasaka M, Kuchiki H, Saino M, Mori W, Sato S, et al. A rare case of extraventricular neurocytoma. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2007;24:19–23. doi: 10.1007/s10014-006-0210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sgouros S, Carey M, Aluwihare N, Barber P, Jackowski A. Central neurocytoma : a correlative clinicopathologic and radiologic analysis. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soylemezoglu F, Scheithauer BW, Esteve J, Kleihues P. Atypical central neurocytoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:551–556. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zentner J, Peiffer J, Roggendorf W, Grote E, Hassler W. Periventricular neurocytoma : a pathological entity. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:38–42. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]