Abstract

Innate immune responses are triggered by the activation of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). The Arabidopsis PRR FLS2 senses bacterial flagellin and initiates immune signaling by association with BAK1. The molecular mechanisms underlying the attenuation of FLS2 activation are largely unknown. We report that flagellin induces recruitment of two closely related U-box E3 ubiquitin ligases PUB12 and PUB13 to FLS2 receptor complex in Arabidopsis. BAK1 phosphorylates PUB12/13 and is required for FLS2-PUB12/13 association. PUB12/13 polyubiquitinate FLS2 and promote flagellin-induced FLS2 degradation, and the pub12 and pub13 mutants displayed elevated immune responses to flagellin treatment. Our study has revealed a unique regulatory circuit of direct ubiquitination and turnover of FLS2 by BAK1-mediated phosphorylation and recruitment of specific E3 ligases for attenuation of immune signaling.

Plants and animals rely on innate immunity to prevent infections by detection of pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs/MAMPs) through pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) (1–4). Arabidopsis FLAGELLIN-SENSING 2 (FLS2), a plasma membrane localized leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK), is the receptor for bacterial flagellin (5). Upon flagellin perception, FLS2 associates instantaneously with another LRR-RLK termed BAK1, which appears to function as a signaling partner of the growth hormone brassinolide receptor BRI1 and multiple PRRs (6–10). BIK1, a receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase in the FLS2/BAK1 complex, is rapidly phosphorylated upon flagellin perception (11–12). Ligand-induced FLS2 endocytosis has also been suggested to be coupled with the activation of flagellin signaling (13). Similar to PRR activation, down-regulation of PRR signaling is crucial for preventing excessive or prolonged activation of immune responses which would be detrimental tothe hosts. Far less is understood as to how the innate immune responses are attenuated following the PRR activation.

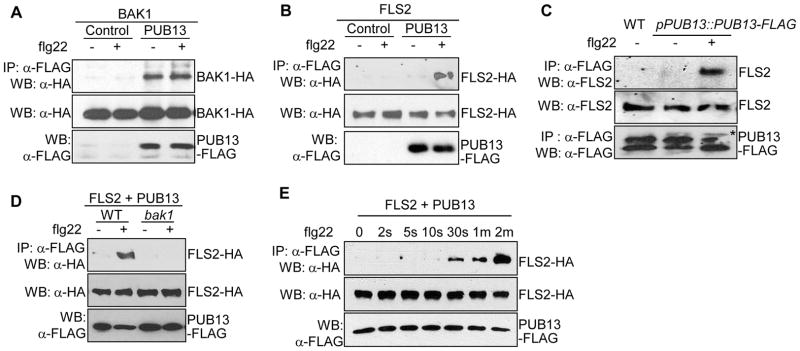

To identify components in MAMP signaling, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using the BAK1 kinase domain as bait. One of the interactors isolated encodes the C-terminus of Arabidopsis PUB13 (At3g46510) (Table S1, Figs. S1 & S2A). PUB13 is a typical Plant U-box (PUB) E3 ubiquitin ligase with a U-box N-terminal Domain (UND), a U-box domain and a C-terminal ARMADILLO (ARM) repeat domain (Fig. S1) (14–15). To test whether full-length PUB13 and BAK1 interact in vivo, we performed a co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay following protoplast transient transfection. FLAG epitope-tagged PUB13 co-immunoprecipitated HA epitope-tagged BAK1 independent of flg22, a 22 amino acid peptide of flagellin (Fig. 1A). The interaction between FLS2 and PUB13 was barely detectable in the absence of flg22 treatment, however, PUB13 strongly associated with FLS2 upon flg22 stimulation (Fig. 1B). Deletion analysis indicated that the ARM domain of PUB13 was sufficient to associate with FLS2 (Fig. S2B). PUB12, the closest homolog of PUB13, but not PUB29, also associated with FLS2 upon flg22 stimulation (Fig. S2C). The association of FLS2 with PUB13 was further confirmed in transgenic plants expressing FLAG-tagged PUB13 under the control of its native promoter (pPUB13::PUB13-FLAG) using an anti-FLS2 antibody (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Flagellin induces BAK1-dependent FLS2-PUB13 complex association. (A) BAK1 interacts with PUB13 in a Co-IP assay. Protoplasts were co-expressed with BAK1-HA and PUB13-FLAG or a control vector. The Co-IP was carried out with an anti-FLAG antibody (IP: α-FLAG), and the proteins were analyzed using Western blot with an anti-HA antibody (WB: α-HA). The top panel shows that BAK1 co-immunoprecipitates with PUB13. The middle and bottom panels show the expression of BAK1-HA and PUB13-FLAG proteins. Protoplasts were stimulated with 1 μM flg22 for 10 min. (B) flg22 induces FLS2-PUB13 association in protoplasts. (C) flg22 induces FLS2-PUB13 association in Arabidopsis seedlings. Twelve-day-old seedlings of pPUB13::PUB13-FLAG transgenic plants were treated with 50 μM MG132 for 1 hr before H2O or 1 μM flg22 treatment for 10 min. * indicates the specific band of PUB13-FLAG in pPUB13::PUB13-FLAG transgenic plants. (D) flg22-induced FLS2-PUB13 association depends on BAK1. (E) flg22 stimulates rapid association of FLS2-PUB13. The above experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Since flg22 induces the association of FLS2 with both BAK1 and PUB12/13, we tested whether flg22-induced FLS2-PUB12/13 association required BAK1. Significantly, flg22-mediated FLS2-PUB13 (Fig. 1D) or FLS2-PUB12 (Fig. S2D) association was not detectable in the bak1-4 mutant plants, indicating that flg22-induced FLS2-PUB12/13 complex formation requires BAK1. However, the interaction of BAK1 and PUB12 does not require FLS2 (Fig. S2E), consistent with the observation that BAK1 constitutively interacts with PUB12 and PUB13 in the absence of ligand (Figs. 1A, S2A & S2E). Similar to the instantaneous association of FLS2 and BAK1, FLS2-PUB13 association was detected within 30 seconds upon flg22 stimulation (Fig. 1E). Together, the results suggest that BAK1 and PUB12/13 likely exist as a complex that is rapidly recruited to FLS2 receptor upon flg22 stimulation (Fig. S2F).

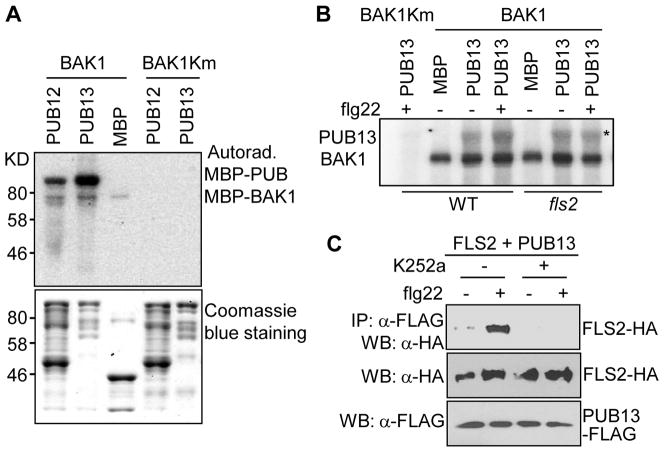

Interestingly, BAK1 directly phosphorylated PUB12 and PUB13 (Fig. 2A). The phosphorylation depended on the kinase activity of BAK1 since a BAK1 kinase mutant (BAK1Km) was unable to phosphorylate PUB12 or PUB13 (Fig. 2A). BIK1, an FLS2/BAK1-associated cytosolic kinase, did not phosphorylate PUB12 or PUB13 (Fig. S3A). However, BIK1 enhanced the ability of BAK1 to phosphorylate PUB13 (Fig. S3A). Consistent with our published data that BIK1 phosphorylates BAK1(11), it is likely that phosphorylation of BAK1 by BIK1 potentiates BAK1’s activity to phosphorylate PUB12 and PUB13. To further examine whether flg22 could enhance BAK1-dependent phosphorylation of PUB13, we performed an immunocomplex kinase assay with flg22-treated protoplasts expressing full length BAK1. The immunoprecipitated BAK1, but not kinase-inactive BAK1Km, phosphorylated PUB13 (Fig. 2B). The phosphorylation of PUB13 was further enhanced upon flg22 treatment depending on its receptor FLS2 (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that PUB12/13 are substrates of BAK1, and that flg22 perception stimulates BAK1 phosphorylation of PUB12/13, which is likely further potentiated by BIK1 (Fig. S3C). To examine the biological significance of PUB12/13 phosphorylation, we tested whether phosphorylation is required for the flg22-induced FLS2-PUB12/13 association. Significantly, we found that the flg22-induced FLS2-PUB13 or FLS2-PUB12 association was blocked by the kinase inhibitor K252a (Figs. 2C & S3B). These results support the significance of phosphorylation events in FLS2-PUB12/13 association (Fig. S3C).

Fig. 2. BAK1 phosphorylates PUB12 and PUB13.

(A) BAK1 phosphorylates PUB12 and PUB13 in vitro. An in vitro kinase assay was performed by incubating MBP fusion protein of BAK1 cytosolic domain (BAK1) or BAK1Km together with MBP, MBP-PUB12 or MBP-PUB13. Phosphorylation was analyzed by autoradiography (top panel), and the protein loading control was shown by Coomassie blue staining (bottom panel). (B) flg22 enhances PUB13 phosphorylation by BAK1. BAK1-FLAG or BAK1Km-FLAG was expressed in WT or fls2 protoplasts for 8 hr followed by 1 μM flg22 treatment for 10 min. BAK1-FLAG was immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody, and subjected to a kinase assay with MBP or MBP-PUB13 as substrate. The top band is phosphorylated PUB13 as indicated with an asterisk *, and the bottom band is BAK1 autophosphorylation. (C) Kinase inhibitor K252a suppresses FLS2 and PUB13 association. The above experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

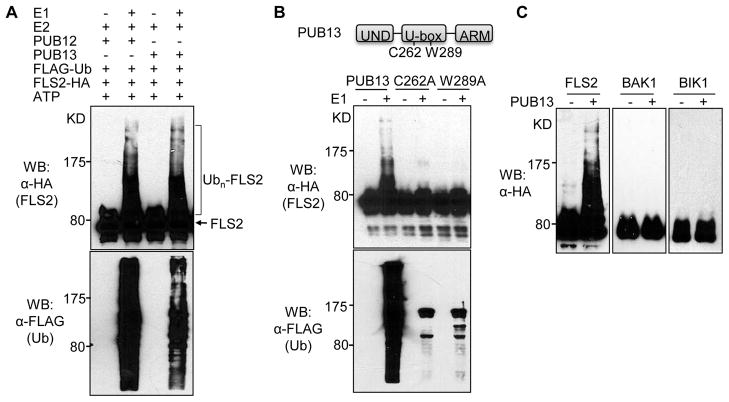

An in vitro ubiquitination assay with GST-PUB12/13 fusion proteins in the presence of recombinant AtUBA1 (E1), AtUBC8 (E2), ATP and FLAG-tagged ubiquitin (Ub) demonstrates that PUB12 and PUB13 possess auto-ubiquitination activity as detected by either anti-FLAG or anti-GST antibody (Fig. S4A). Significantly, both PUB12 and PUB13 polyubiquitinated the cytosolic domain of FLS2 evidenced by detection of a ladder-like smear with high-molecular-weight proteins (Fig. 3A). Eliminating E1, E2, PUB13, Ub or ATP from the reaction blocked the ladder formation for FLS2 (Fig. S4B). Mutation of the conserved cysteine or tryptophan residue to alanine (C262A or W289A) within the U-box motif of PUB13 abolished its ubiquitin ligase activity on FLS2 (Fig. 3B). The specificity of FLS2 ubiquitination by PUB12 and PUB13 was further substantiated by the observation that several U-box E3 ubiquitin ligases, including PUB14 and PUB29, did not ubiquitinate FLS2 (Fig. S4C). Interestingly, PUB12 and PUB13 did not ubiquitinate the cytosolic domain of BAK1 or BIK1 (Fig. 3C). Thus, PUB12 and PUB13 specifically ubiquitinate the PRR FLS2, but not the signaling components BAK1 or BIK1 (Fig. S5C).

Fig. 3. PUB12 and PUB13 ubiquitinate FLS2.

(A) PUB12 and PUB13 ubiquitinate FLS2. The HA-tagged FLS2 cytosolic domain was purified as MBP fusion protein. The ubiquitination of FLS2 was detected by an anti-HA antibody. The overall ubiquitination was detected by an anti-FLAG antibody. (B) C262 and W289 are required for PUB13 E3 ligase activity. (C) PUB13 ubiquitinates FLS2, but not BAK1 or BIK1. The above experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

It has been shown that flg22 induces FLS2 translocation into intracellular vesicles, which is followed by degradation of FLS2 (13). FLS2 possesses a PEST-like motif in the C-terminus, required for FLS2 endocytosis. In addition, a potential phosphorylation site, Thr 867, is essential for FLS2 internalization and signaling (13). However, neither the T867V nor a PEST mutant P1076A abolished FLS2 ubiquitination by PUB13 or PUB12 (Fig. S5A), suggesting that FLS2 ubiquitination and internalization are likely uncoupled. It has been reported that the ubiquitination of FLS2 by a bacterial effector AvrPtoB is also independent of its PEST domain (16). An FLS2 kinase inactive mutant K898M also did not affect FLS2 ubiquitination by PUB13 (Fig. S5B), indicating that FLS2 kinase activity is not required for its ubiquitination. This is consistent with our data that PUB12/13 are phosphorylated by BAK1 and phosphorylation is required for flg22-induced FLS2-PUB12/13 association. Our data also suggest that FLS2 ubiquitination is distinct from mammalian receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), in which a kinase-defective mutant blocked RTK ubiquitination (17).

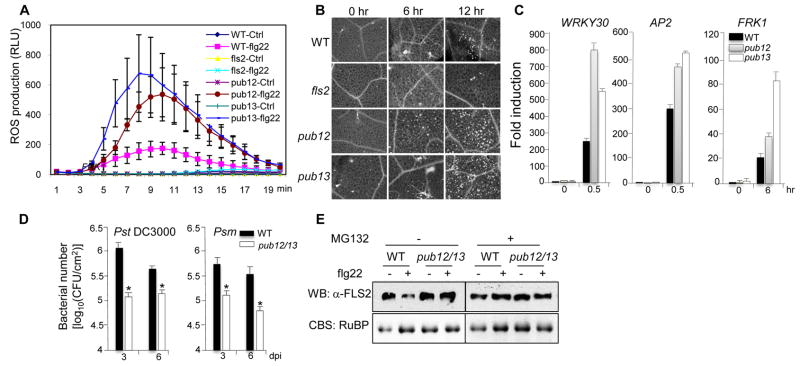

To further demonstrate the biological function of PUB12 and PUB13 in plant innate immunity, we isolated their T-DNA insertional mutants. RT-PCR analysis indicated that pub12-1 (SAIL_35_G10) displayed a slight reduction of transcript, while pub12-2 (WiscDsLox497_01) showed a pronounced transcript reduction and was selected for further analyses (Fig. S6). The pub13 mutant (SALK_093164) is a null mutant with undetectable transcript (Fig. S6). We examined the immune responses in wild-type (WT), pub12-2 and pub13 mutants. Flg22-induced FLS2/BAK1 association (Fig. S7A) and BIK1 phosphorylation (Fig. S7B) occurred similarly in pub12-2 and pub13 mutants and in WT plants, suggesting that PUB12 and PUB13 are not required for flg22 perception by FLS2. When treated with flg22, pub12-2 and pub13 mutants accumulated two- to threefold more H2O2 production than WT plants (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the pub12-2 and pub13 mutants showed more callose deposits than WT plants (Figs. 4B & S6C). The complementation lines of the pub13 mutants transformed with a pPUB13::PUB13-FLAG construct displayed a similar level of H2O2 production (Fig. S8A) and callose deposition (Figs. S8B & S8C) as the WT plants upon flg22 stimulation. Compared to WT plants, the induction of immune responsive genes, WRKY30, AP2 (At3g23230) and FRK1, was further enhanced in the pub12-2 and pub13 mutants upon flg22 treatment (Fig. 4C). Notably, the basal expression level of these genes was comparable in WT and pub12-2 or pub13 mutants, suggesting that pub12-2 and pub13 mutants are not constitutively expressing immunity-related genes. Together, these data indicate that flg22-mediated responses are potentiated in the pub12 and pub13 mutants, and that PUB12 and PUB13 play a negative role in FLS2 signaling.

Fig. 4. Function of PUB12 and PUB13 in FLS2 signaling.

(A) ROS burst in Arabidopsis leaves triggered by flg22. Leaf discs were treated with H2O (Ctrl) or 100 nM flg22. The data are shown as means ± standard errors from 40 leaf discs. (B) flg22-induced callose deposition. Leaves were treated with 1μM flg22 for 6 and 12 hr. (C) flg22-induced gene induction. Twelve-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings were treated with 10 nM flg22 for 0.5 or 6 hr. The data are shown as means ± standard errors from 3 independent biological repeats. (D) The bacterial growth assay of DC3000 and Psm. Four-week-old Arabidopsis plants were inoculated with bacteria at a concentration of 5×105 cfu/ml. The data are shown as means ± standard errors from 3 replicates. * indicates a significant difference with p<0.05 when compared with data from WT plants. (E) PUB12/13 promote FLS2 degradation. Twelve-day-old seedlings were treated with or without 50 μM MG132 for 1 hr before 1 μM flg22 treatment for 0.5 hr. The equal protein loading was shown by Coomassie blue staining (CBS) for RuBisCo (bottom panel). The above experiments were repeated three to four times with similar results.

We performed pathogen infection assays with WT and pub mutants. Neither pub12-2 nor pub13 mutants showed significantly altered disease symptoms or bacterial multiplication following Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 infection compared to WT plants (Fig. S9A). To reveal potentially functional redundancy, we generated a pub12/13 double mutant. The pub12/13 mutant did not display any obvious growth defects under normal growth conditions (data not shown), which is consistent with that pub12-2 and pub13 mutants did not constitutively activate immunity-related genes. Alternatively, additional components might play redundant functions with PUB12 and PUB13 in the control of detrimental effect of constitutively active defense systems. Importantly, the pub12/13 mutant was more resistant to DC3000 infection than WT plants. Three days after infection, the bacterial population in the pub12/13 mutant was about 10-fold lower than that in WT plants (Fig. 4D). The disease symptoms were also less severe in the pub12/13 mutant compared to WT plants six days after infection (Fig. S9B). Similarly, the pub12/13 mutants were also more resistant to P. syringae maculicola ES4326 infection as measured by bacterial growth and disease symptoms (Figs. 4D & S9B).

Ubiquitination could lead to protein degradation, or in some cases, modulation the activity or localization of a protein target. We examined FLS2 protein level in WT and the pub12/13 mutant with an anti-FLS2 antibody. We repeatedly observed an apparent reduction of FLS2 protein level within 30 min after flg22 treatment in WT plants (Fig. 4E), which is consistent with the report of ligand-induced FLS2 endocytosis/degradation (13). This degradation was diminished by treatment with MG132, an inhibitor of proteasome-mediated degradation (Fig. 4E), suggesting the involvement of the 26S proteasome in FLS2 degradation. Importantly, FLS2 protein level was not significantly reduced in the pub12/13 mutant treated with flg22 (Figs. 4E & S10A), suggesting the involvement of PUB12 and PUB13 in flg22-mediated FLS2 degradation. Similar to the pub12/13 mutant, the reduced FLS2 level triggered by flg22 was not evident in the bak1-4 mutant (Fig. S10B). This is consistent with the FLS2-PUB12/13 association being dependent on BAK1 (Figs. 1D & S2D). We further developed an in vivo ubiquitination assay with protoplast transient transfection of FLAG-tagged UBQ10. The treatment of flg22 enhanced FLS2 ubiquitination as detected by an anti-FLS2 antibody (Fig. S10C). The flg22-mediated FLS2 ubiquitination was reduced in the pub12/13 mutant (Fig. S10C), which substantiates the role of PUB12/13 in the ubiquitination of endogenous FLS2 (Fig. S11).

Ubiquitination has been implicated in plant innate immunity (18–19). Two Avr9/Cf9 rapidly elicited PUB genes are required for programmed cell death and defense in tobacco, tomato and Arabidopsis (20–21). Three closely related Arabidopsis PUBs, PUB22/23/24, negatively regulate flagellin signaling (22). Rice SPL11, one of the closest homologs to PUB12/13, is a negative regulator of plant cell death (23). Similarly, a rice RING finger E3 ligase XB3 could be phosphorylated by PRR XA21 mediating bacterial resistance (24). However, the modes of action of these E3 ligases from upstream activators to downstream substrates are largely unknown. Identification of PUB12/13 as negative regulators of flagellin signaling by direct ubiquitination of FLS2 not only contributes to the general understanding of innate immune signaling, but also improves our ability for genetic manipulation of disease resistant crop plants without deleterious side effects.

Ubiquitination-mediated Toll-like receptor (TLR) degradation serves as one of the mechanisms to down-regulate TLR signaling (25). Triad 3A, an RING finger E3 ligase mediating ubiquitination and proteolytic degradation of TLR4 and TLR9, appears to be analogous to PUB12/13 in Arabidopsis FLS2 signaling (25). However, the regulation and activation of TLR ubiquitination remain unknown. The mechanism of activating FLS2 ubiquitination is also unique and distinct from RTK signaling (Fig. S11). The ubiquitination of RTKs is regulated by ligand-induced RTK phosphorylation (26). It appears that FLS2 phosphorylation is not required for its ubiquitination (Figs. S5A & S5B). Instead, phosphorylation appears to be required for flg22-induced FLS2-PUB12/13 association (Fig. 2C & S3B). It is plausible that phosphorylation of PUB12/13 promotes their association with FLS2 in vivo (Fig. S11). More interestingly, ubiquitination only occurs on FLS2 not BAK1, a common signaling partner of multiple membrane receptors involved in immunity and development. This suggests a mechanism of how the specificity of the signal output is determined for a shared signaling component.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Fred Ausubel, Jim Alfano, Marty Dickman and Herman Scholthof for critical reading of the manuscript, Dr. Filip Rolland for the yeast two-hybrid vectors. We also thank the Salk Institute and Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center for the Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion lines. This work was supported by NSF (IOS-1030250) to L.S. and NIH (R01GM092893) to P.H.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Cell. 2010 Mar 19;140:805. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boller T, Felix G. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:379. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones JD, Dangl JL. Nature. 2006 Nov 16;444:323. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodds PN, Rathjen JP. Nat Rev Genet. 2010 Aug;11:539. doi: 10.1038/nrg2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T. Mol Cell. 2000 Jun;5:1003. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinchilla D, et al. Nature. 2007 Jul 26;448:497. doi: 10.1038/nature05999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heese A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 17;104:12217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705306104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, et al. Cell. 2002 Jul 26;110:213. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nam KH, Li J. Cell. 2002 Jul 26;110:203. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulze B, et al. J Biol Chem. 2010 Mar 26;285:9444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu D, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jan 5;107:496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909705107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, et al. Cell Host Microbe. 2010 Apr 22;7:290. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robatzek S, Chinchilla D, Boller T. Genes Dev. 2006 Mar 1;20:537. doi: 10.1101/gad.366506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yee D, Goring DR. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1109. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azevedo C, Santos-Rosa MJ, Shirasu K. Trends Plant Sci. 2001 Aug;6:354. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01960-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gohre V, et al. Curr Biol. 2008 Dec 9;18:1824. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levkowitz G, et al. Mol Cell. 1999 Dec;4:1029. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig A, Ewan R, Mesmar J, Gudipati V, Sadanandom A. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:1123. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trujillo M, Shirasu K. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010 Aug;13:402. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang CW, et al. Plant Cell. 2006 Apr;18:1084. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Lamothe R, et al. Plant Cell. 2006 Apr;18:1067. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.040998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trujillo M, Ichimura K, Casais C, Shirasu K. Curr Biol. 2008 Sep 23;18:1396. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng LR, et al. Plant Cell. 2004 Oct;16:2795. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang YS, et al. Plant Cell. 2006 Dec;18:3635. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuang TH, Ulevitch RJ. Nat Immunol. 2004 May;5:495. doi: 10.1038/ni1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell. 2010 Jun 25;141:1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.