Abstract

Informal payments are a frequently overlooked source of local public finance in developing countries. We use microdata from ten countries to establish stylized facts on the magnitude, form, and distributional implications of this “informal taxation.” Informal taxation is widespread, particularly in rural areas, with substantial in-kind labor payments. The wealthy pay more, but pay less in percentage terms, and informal taxes are more regressive than formal taxes. Failing to include informal taxation underestimates household tax burdens and revenue decentralization in developing countries. We discuss various explanations for and implications of these observed stylized facts.

1 Introduction

A key function of government is the finance and provision of local public goods. Taxation allows communities to overcome the free rider problem that would otherwise lead to underprovision of these goods. In many developing countries, formal direct taxation of households is limited, comprising only 18% of total tax revenues on average compared with 45% in developed countries (Roger Gordon and Wei Li 2009).1 Agricultural sectors are often entirely exempt from taxation, and local taxation is generally quite constrained (Richard M. Bird 1990; Robin Burgess and Nicholas Stern 1993). These facts would suggest that local public goods are primarily financed outside the local community, either through direct provision or intergovernmental grants.

Substantial anecdotal evidence, however, suggests that local residents in many communities throughout the developing world do contribute substantially – outside the formal tax system – to the construction and maintenance of local public goods (e.g., Elinor Ostrom 1991). People pay in both money and labor to these projects, with often complex arrangements determining how much each household should pay and what penalties apply for those who free ride. Many countries even have specific vocabulary to describe these systems, such as gotong royong in Indonesia and harambee in Kenya.

We refer to these mechanisms of financing of local public goods as “informal taxation.” We define informal taxation as a system of local public goods finance coordinated by public officials but enforced socially rather than through the formal legal system.2 Our distinction between formal and informal (legal versus social enforcement) parallels the use of these terms in the informal insurance literature (e.g. Robert Townsend 1994). The involvement of public officials, discussed in more detail below, distinguishes informal taxation from, for example, provision of local public goods by charities or other non-governmental organizations.

In this paper, we develop some of the first systematic micro-evidence on the magnitude, distributional implications, and forms of informal taxation, using a micro dataset we assembled consisting of survey data from ten developing countries throughout the world. We then discuss a variety of potential explanations for the phenomenon and the broader implications of our findings for public finance and policy in developing countries.

The first stylized fact we document is that informal taxation is a widespread phenomenon, and it can form a substantial share of local revenue. The share of households making informal tax payments is 20% or higher in all but one country in our sample and exceeds 50% in several countries. Participation rates are always higher in rural areas than in urban areas. Across our sampled countries, informal taxes generally comprise a small share of household expenditure (0.85% in the median country) and a modest share of total taxes paid by households (15.7% in the median country). However, informal taxes can still be an important source of local public finance. In our Indonesia sample, for example, including informal taxes increases the estimates of the amount of revenue under local control by over 50%.

The second stylized fact we document is that, within individual communities, informal taxation is redistributive but regressive. Wealthier households in a community are generally more likely to participate in informal taxation schemes than poorer households. The elasticity of total payment with respect to household expenditure is positive but less than one in all countries, indicating that informal taxes rise with expenditure, but the average informal tax rate (i.e., informal taxes divided by total expenditure) falls with expenditure. Informal taxation is therefore regressive, but still provides redistribution if the local public good it finances is valued equally across the income distribution. Informal taxes are more regressive than formal taxes, both within communities and when examined in aggregate at the national level.

The third stylized fact we document is that the form of payment differs from a traditional tax; in particular, in-kind labor payments play a substantial role in informal taxation. Moreover, both the participation gradient and the elasticity of payment with respect to household expenditure are smaller for labor payments than for money payments, so that labor payments are relatively more important for poorer households. All three stylized facts we observe are remarkably consistent across countries.

We then consider a variety of possible explanations for the observed stylized facts. First, informal taxation may be a response to constraints on the revenue raising capacity of local governments: informal taxes may be the only way for these governments to meet their demand for public goods. Second, informal taxation may arise as the solution to a constrained optimal tax problem even when formal taxation is available. In particular, if communities in developing countries have information about people’s incomes that is not verifiable by courts (and therefore cannot be used in a formal tax system), it may be optimal to levy informal taxes to use this information. Third, informal tax payments may represent a user fee or benefits tax for the associated public goods provided. Finally, these payments may represent purely voluntary contributions to community projects, motivated by altruism.

In Section 5, we discuss these (non mutually exclusive) hypotheses as well as their relation to the empirical evidence on informal taxation. A limit to the constraints on formal taxation story is that it does not make direct predictions about the form or distribution of payments. In contrast, the optimal tax story can reconcile many of the observed facts (prevalence in rural areas, positive income gradients, and the prevalence of labor payments), although we do find that in cases where the good is excludable, such as water supplies or schools, informal taxes may behave more like a type of user fee. Finally, while payments may be at least partly motivated by altruism, survey evidence from Indonesia suggests that informal tax payments cannot be thought of as purely akin to charitable contributions: when asked who decides which households should participate, for example, only 8% of households report that they decide for themselves; 81% report that a local leader decides.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the existing literature and Section 3 describes the data. Section 4 presents the stylized facts. Section 5 considers various explanations for the observed stylized facts. Section 6 discusses the implications of our findings and concludes.

2 Existing Evidence on Informal Taxation

As noted above, we define informal taxation as a system for financing local public goods, characterized by social enforcement and the involvement of public officials. Qualitative evidence from a variety of settings suggests that informal taxation is a common form of local finance for the construction and maintenance of public goods such as roads, schools, and water systems throughout the developing world (e.g., Ostrom 1991), although formal empirical evidence on informal taxation remains fairly limited. A range of studies have documented the presence of informal taxation in various countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.3

In many of these countries, informal tax systems appear to form a very important component of community development. In Indonesia, for example, the concepts of gotong royong (mutual assistance) and swadaya (self-help) have become deeply institutionalized within local communities: residents are expected to make labor and monetary payments toward development projects – for example, 37% of the cost of village public goods examined by Rao (2004) in Indonesia are contributed by the community. In Kenya, harambee (pull together) projects accounted for 11.4% of national development expenditure between 1967 and 1973, and harambee-financed spending on particular sectors, such as education, matched or exceeded government expenditure (Mbithi and Rasmusson 1977).

Several patterns emerge from the range of anecdotes and studies of informal taxation. First, payments do not appear to be chosen by households individually. Rather, expected payments are generally coordinated by community leaders or a project committee. Households may be expected to provide a given monetary payment, as in the case of school fees in Kenya (Miguel and Gugerty 2005), or provide a certain number of days of labor (Ostrom 1991; Sharon R. Roseman 1996). In some cases, there may be a choice between paying in labor or in money (Njoh 2003).

Second, many of these studies document the existence of non-contributers and describe a range of punishments that may be imposed on such individuals. Miguel and Gugerty (2005) provide several anecdotal examples of social sanctions in the context of school financing in western Kenya.4 A common sanction is the public announcement of the names of parents who are late with fees; other forms of sanctions include “sending letters to the homes of parents late with fees, asking local church leaders to encourage payment during sermons, and making personal visits to the individual homes of debtors accompanied by the local Chief” (Miguel and Gugerty 2005). Other examples of punishments include fines (Ostrom 1991) and the denial of access to communal resources, such as the use of a cattledip (Thomas 1987).5 It is possible that punishments could also include exclusion from community credit or risk-sharing arrangements or other types of social enforcement, as in the informal insurance and microfinance literatures.

Our own direct experience with informal taxation in a village in Central Java, Indonesia, echoes many of these themes. In 2002, a village where one of the authors was staying received 29 drums of raw asphalt from the district government. In order to make use of the raw asphalt to resurface a road, the village needed to raise funds for additional materials (e.g., finely crushed gravel, coarse gravel, sand) as well as labor. To solve this problem, the village head called a meeting in the neighborhood where the road would be built. At that meeting, the village head, neighborhood head and an informal community leader (a local school teacher) went around the room “assigning” payments to each household. These payments increased with income: poorer households would be asked to pay a small amount (usually a few days of labor), whereas wealthier households were asked to pay in money, with the wealthiest households asked to pay the most. The meeting did not specify what sanctions would be for non-payment; however, given that payments were assigned in a public meeting, one can presume that there would have been social pressure applied to those who failed to meet their assigned payment level.

To the best of our knowledge, quantitative work on the distribution of informal tax burdens has focused on two countries: Indonesia and Kenya. Beard (2007) finds that Indonesian households with more assets or more education pay more in labor and money toward informal taxation; those with high household expenditure pay less. Note that these effects are not unconditional: regressions include all of these factors as independent variables. In surveys of particular communities in Kenya, Thomas (1987) finds that labor payments are widespread and that the rich are more likely to make cash payments than the poor, and Barkan and Holmquist (1989) find that participation and labor payments tend to follow an inverse U-shape with respect to landholding while payments in cash are increasing in landholding.

An open question is whether or not informal tax mechanisms appear similar across the broad range of countries in which they are observed. In the next sections of the paper, we provide systematic cross-country evidence to document several stylized facts about informal taxation.

3 Data

We compiled microdata from around the world to create a dataset that covers the phenomenon of informal taxation in as many countries as possible. We examined over 100 household surveys, including (but not limited to) every publicly available World Bank Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) survey.6 To be included in our sample, a survey needed to elicit information specifically about payment towards the provision of local public goods. A typical example of such a question is: “In the last 12 months did you personally or any other member of the household participate in any of the following … participate in the collective construction of community works (roads, schools etc.).”7 Our sample includes every household survey that met this criterion. We did not include surveys that asked only about labor sharing agreements among neighbors or contributions to local social organizations or cases in which the labor was clearly compensated, such as paid public works days.8

In addition to these pre-existing datasets, we designed a special survey module on informal taxation for the Health and Education Service Survey in Indonesia. This survey module included detailed questions on labor and monetary payments as well as questions on the decision-making process and enforcement of informal taxation not available on the other surveys in the sample. The Indonesia survey was conducted by Gadjah Mada University and The World Bank as a baseline survey for a poverty-alleviation program. The survey took place in 5 provinces from June-September 2007, and covered a total of 12,000 households in over 2,300 villages. More details about the survey can be found in Benjamin A. Olken, Junko Onishi, and Susan Wong (2008).

The types of community works mentioned on these surveys include roads, water and sanitation systems, schools, health centers, dams and irrigation systems, electricity systems, and cleaning of public roads and areas.9 While we refer to these goods as local public goods, they may be excludable in some cases. We return to this issue in Section 5.

The resulting sample consists of household surveys from 10 countries: Albania, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Indonesia, Nigeria, Nicaragua, Panama, the Philippines, Vietnam and Zambia. A potential concern with our sample of countries is that relevant survey questions are more likely to be included in countries where the phenomenon is prevalent. However, we can see that informal taxation is not geographically isolated to a particular region of the world: the sample contains countries from Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. In addition, as discussed in Section 2, anecdotal evidence indicates that informal taxation is common in many other countries that are similar to our sampled countries.

Table 1 provides an overview of our sample of household surveys. The surveys were conducted between 1997 and 2007, and sample sizes range from approximately 1,500 to 30,000. The surveys are nationally representative with the exceptions of Ethiopia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, which were conducted in rural areas only. Indonesia and the Philippines focus on a poorer-than-average selection of rural areas, since both surveys were conducted as baseline surveys for poverty alleviation programs. As shown in the table, all surveys contain information on in-kind labor payments toward public goods; monetary payments and quantity data are available for subsets of countries. Note that the recall period varies across surveys: while most surveys ask about payments over the past year, one survey (Philippines) asks only about the previous six months and two surveys (Nicaragua and Zambia) ask about the previous 5 years (Web Appendix A provides more details on the specific questions and survey sample for each country).

Table 1.

Data sources

| Database Name | Year | Sample | Sample size (number of households) | Recall period | Labor

|

Money

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payment indicator | Quantity | Payment indicator | Quantity | ||||||

| Albania | Living standards measurement survey | 2005 | Nationally representative | 3,840 | 1 year | X | X | ||

| Ethiopia | Ethiopian rural household survey | 1997 | Only rural areas | 1,482 | 1 year | X | X | ||

| Guatemala | National survey of living conditions | 2000 | Nationally representative | 7,276 | 1 year | X | |||

| Indonesia | Health and education service survey | 2007 | Only rural areas, focus on poorer areas | 11,676 | 1 year | X | X | X | X |

| Nicaragua | Living standards measurement study survey | 1998 | Nationally representative | 4,209 | 5 years | X | X | ||

| Nigeria | Nigeria living standards survey | 2004 | Nationally representative | 19,159 | 1 year | X | |||

| Panama | Living standards survey | 2003 | Nationally representative | 6,363 | 1 year | X | X | ||

| Philippines | Living condition Survey | 2003 | Only rural areas, focus on poorer areas | 2,398 | 6 months | X | X | ||

| Vietnam | Household living standards survey | 2002 | Nationally representative | 29,426 | 1 year | X | X | X | X |

| Zambia | Living condition monitoring survey | 1998 | Nationally representative | 16,788 | 5 years | X | X | ||

Notes: For more details on each of the surveys, please see Appendix A.

Summary statistics for each survey are given in Table 2. The summary statistics (as well as per-capita GDP from the World Development Indicators) indicate the breadth of countries covered by our data. For example, per-capita GDP in the surveyed countries ranges from a low of PP$774 in Zambia to a high of PP$6129 in Panama, and mean years of education for the household head ranges from a low of 2.5 in Ethiopia to a high of 9.6 in Albania.

Table 2.

Summary statistics

| Albania | Ethiopia | Guatemala | Indonesia | Nicaragua | Nigeria | Panama | Philippines | Vietnam | Zambia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | 4.4 | 7.3 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 5.4 |

| Number of workers per household | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.9 |

| Expenditure per capita (in PPP $) | 3396 | 554 | 2338 | 1112 | 2850 | 489 | 3514 | 938 | 1368 | 744 |

| GDP per capita (in 2000 PPP$) | 4731 | 814 | 4048 | 3423 | 2910 | 941 | 6129 | 4250 | 2274 | 774 |

| % urban | 47 | 0 | 43 | 0 | 57 | 45 | 64 | 0 | 24 | 36 |

| Age (Household head) | 52 | 47 | 44 | 47 | 45 | 48 | 48 | 47 | 48 | 41 |

| Years of education (Household head) | 9.6 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 8.3 | 5.7 | 7.0 | 6.6 |

Notes: Each cell presents the mean of the variable in the row in the dataset listed in the column weighted using household weights (available for all countries except Ethiopia). When GDP is not available for the survey year, we used the most recent data.

We include survey data from all available countries in our empirical analysis in order to paint as complete a picture as possible of the informal taxation phenomenon. One caveat, however, is worth noting explicitly. To the best of our knowledge, public labor contributions are legally mandated in Vietnam. If an individual cannot fulfill his required contribution, he must find a replacement worker or make a monetary payment equivalent to hiring a replacement at local labor costs.10 The payments observed in Vietnam may therefore be a formal tax rather than an informal tax.

4 Stylized Facts and Implications

This section presents several stylized facts about informal taxation. We focus on the following questions that are relevant when thinking about any tax: where is it most prevalent? how large is it? who pays it? and how is it collected? The first subsection summarizes the prevalence and magnitude of informal taxation and compares the magnitude of informal taxation to formal tax payments made by households and to formal government expenditure. In the second subsection, we examine the distributional implications of informal tax payments and discuss the progressivity of informal taxation relative to formal taxation. The third subsection discusses how these taxes are collected and explores a feature of informal taxation that sharply distinguishes it from conventional taxation: payments are often in labor rather than money. The final subsection provides a brief discussion of the implications of these findings for public finance in developing countries.

4.1 Prevalence and Magnitude of Informal Taxation

4.1.1 Descriptive statistics on prevalence and magnitude

We begin by presenting descriptive statistics to examine the most basic question about informal taxation: prevalence. Table 3 presents three sets of descriptive statistics: the share of households making informal taxation payments over the recall period (Panel A), the share of households making in-kind labor payments vs. payments in money and materials (Panel B), and the average amounts of those payments (Panel C) for each country in our sample.11

Table 3.

Summary of informal tax payments

| Philippines | Albania | Ethiopia | Guatemala | Indonesia | Panama | Nigeria | Vietnam | Nicaragua | Zambia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall Period | 6 months | 1 year | 1 year | 1 year | 1 year | 1 year | 1 year | 1 year | 5 years | 5 years | ||

| Panel A | Any payment | All | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.59 | 0.20 | 0.23 |

| Rural | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.26 | 0.27 | ||

| Urban | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Panel B | Any labor payment | All | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| Rural | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.23 | ||

| Urban | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.08 | |||||

| Any money payment | All | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Rural | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |||||||

| Urban | 0.18 | 0.45 | 0.08 | 0.09 | ||||||||

| Both money and labor payments | All | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Rural | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Urban | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Panel C | Amount of labor payment (in days) | All | 1.1 (4.2) | 0.2 (0.6) | 14.1 (28.3) | 5.7 (13.2) | 3.1 (7.3) | |||||

| Rural | 1.1 (4.2) | 0.2 (0.6) | 14.1 (28.3) | 5.7 (13.2) | 3.5 (7.7) | |||||||

| Urban | 0.1 (0.6) | 1.6 (5.6) | ||||||||||

| Conditional amount of labor payment (in days) | All | 3.3 (6.8) | 1.8 (1.2) | 27.6 (34.6) | 7.5 (14.7) | 12.8 (9.8) | ||||||

| Rural | 3.3 (6.8) | 1.6 (1.0) | 27.6 (34.6) | 7.5 (14.7) | 12.8 (9.7) | |||||||

| Urban | 2.1 (1.3) | 12.9 (10.1) | ||||||||||

| Amount of money payment (in 2000 PPP US$) | All | 8.9 (167.4) | 13.5 (19.8) | |||||||||

| Rural | 8.9 (167.4) | 13.2 (18.4) | ||||||||||

| Urban | 14.5 (23.6) | |||||||||||

| Conditional amount of money payment (in 2000 PPP US$) | All | 32.5 (318.2) | 27.2 (20.4) | |||||||||

| Rural | 32.5 (318.2) | 25.8 (18.3) | ||||||||||

| Urban | 31.9 (25.8) | |||||||||||

Notes: Each cell presents the mean of the variable listed in the row in the dataset listed in the column weighted using household weights (available for all countries except Ethiopia). The unit of observation is the household. Some surveys only contained information about labor payments; for these surveys, participation rates given in Panel A will be identical to participation rates for “any labor payment” given in Panel B.

Notes: The figures in Panel C represent annualized quantities; numbers in parentheses indicate standard deviations. For reference in interpreting the monetary amounts in Panel C, the average annual per capita expenditure in these samples (in PPP$) is 1112 for Indonesia and 1368 for Vietnam. Conditional amounts reported are conditional on making any payment. Weighted using household weights (available for all countries except Ethiopia).

Informal taxation is prevalent in all surveyed countries (Panel A). With the exception of Albania, participation rates are 20% or higher in all countries and exceed 50% in Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Informal taxation is more prevalent in rural areas in every country in our sample for which we have data on both. Across the sample, participation rates are between 27% (Vietnam) and 183% (Guatemala) higher in rural areas than in urban areas.

In-kind payments in the form of labor are common in all countries (Panel B). The share of households paying in labor is higher than the share of households paying in money in 3 of the 5 countries for which we have data on both labor and monetary payments (Indonesia, Nicaragua, and Zambia). In the other two countries (Panama and Vietnam), labor payments are still quite common, with 19 and 24 percent of households making payments in labor, respectively. The gap between urban and rural is smaller for monetary payments than for labor payments in all cases.

Panel C shows the magnitude of informal tax payments for all countries for which quantity data are available. The figures shown represent annualized labor payments (in days) and annualized monetary payments (in 2000 PPP US dollars). Average labor payments vary from 0.2 days per year in Albania to 14.1 days per year in Ethiopia.

4.1.2 Informal taxes and formal taxes paid by households

To better gauge the magnitude of informal taxation, we compare it to two types of benchmarks. In this subsection, we examine the burden it imposes on households by comparing informal tax payments to household expenditure and to total taxes paid by households. These benchmarks are available for the same households for whom we have data on informal taxation payments, ensuring consistent samples for comparison. In the next subsection, we compare informal taxation to government budgets.

In order to make these comparisons, we monetize the labor payments made by households to construct a measure of total informal tax payments. To do so, for each country we predict the wage for all working household members based on their education, age, gender, and urban/rural status, and value the labor contributions at the average predicted wage for all working household members. We use the predicted daily wage rate, rather than the household daily wage rate, so that when we regress payments on household expenditures below, we will not be using expenditures on both the left hand and right hand sides of the same regression.12 This method values the marginal and average wage of the household equally. This assumption is consistent with Dwayne Benjamin (1992) who shows that household composition does not affect own-farm labor supply for agricultural households in Indonesia, suggesting that labor markets for these households are competitive and complete. Using predicted wages measures the magnitude of informal taxation as the social cost of production, which may differ from the value of output produced if the opportunity cost differs from the marginal product on the project.

It is important to note the implications of using the household’s predicted wage rate to monetize days of contributions, rather than a measure of the “true” wage. First, taking the average predicted wage across the household, rather than trying to estimate the wage for each individual, means that if contributions are made by those with the lowest opportunity cost of time, our estimate of the average household wage may be an overestimate. On the hand, it is possible that some people who are listed as “working” in the household do not work a full 260 work days per year, which would lead us to underestimate their true wage rate, or that those who contribute are prime-age males with a higher marginal product than the average in the household. Second, predicting the household’s wage rate using demographics, rather than using total consumption divided by total number of works, has the advantage of removing variation arising from unearned income or labor supply, which would otherwise lead to an upward bias in the estimated wage; however, it also does not take into account dimensions of skill not captured by the included demographics, which could lead to a downward bias. The ideal thought experiment would be to measure the true marginal wage for each household member at the time of year they contribute to informal taxes, though this is not feasible in our data. As an alternative, we therefore discuss specifications using labor measured in days rather than monetized days below.

Income data from developing country household surveys is often unreliable, so we follow the standard convention of using household expenditures as a proxy for household income throughout the paper. Specifically, we use an equivalence scale adjusted measure of household expenditure to take into account children in the household and economies of scale. (Details provided in Web Appendix A.) As an alternative, we have verified that all empirical results are qualitatively similar if we use log total household expenditure and a set of household size dummies instead of log equivalent expenditure.

Data on total tax payments comes from two sources. Direct formal taxes paid by households are calculated as the sum of all direct tax payments observed in the data, and include items such as land and buildings taxes and personal income taxes. Indirect formal taxes (VAT) are imputed from consumption data and commodity specific VAT and excise rates for each country. We do not include expenditures on food in our VAT estimates, since most households in developing countries are unlikely to pay VAT on most food consumption in practice; nevertheless, we may be overestimating VAT if evasion on non-food items is prevalent. Total formal taxes are the sum of direct and imputed indirect taxes. Further details on the calculation of direct and indirect taxes are given in Web Appendix A.

Using this data, we calculate informal taxes as a share of total household expenditure and informal taxes as a share of total household taxes (informal + direct formal + indirect formal). Table 4 presents the mean of these variables for each country in the dataset. Since some households may live in areas where informal taxation does not occur, we present both results for all households (rows 1 and 3) and for all households that have non-zero informal tax payments (rows 2 and 4).

Table 4.

Informal Taxation, Expenditure, and Formal Taxation

| Philippines | Albania | Ethiopia | Indonesia | Vietnam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal tax as a share of HH expenditure | |||||

| All households | 0.23% | 0.04% | 3.77% | 1.43% | 0.85% |

| Conditional on informal tax > 0 | 0.66% | 0.37% | 6.81% | 1.83% | 1.41% |

| Informal tax as a share of HH Total Formal + Informal Tax payments | |||||

| All households | 6.94% | 0.48% | 26.8% | 16.56% | 15.70% |

| Conditional on informal tax > 0 | 20.36% | 4.57% | 49.22% | 21.15% | 26.07% |

Notes: The included countries are the countries for which we have quantity data on informal tax payments. Please see Appendix A for details on the formal tax payment calculations. Weighted using household weights (available for all countries except Ethiopia).

Overall, informal taxation appears to comprise a small share of household expenditure, although there is substantial heterogeneity across countries. Mean informal taxation payments range from a low of 0.04% of household expenditure in Albania to a high of 3.8% in Ethiopia. Conditional on making any informal tax payments, shares range from 0.37% (Albania) to 6.8% (Ethiopia).

Informal taxes are a moderate share of total taxes paid by households: mean shares are 0.5% in Albania, 7% in the Philippines, 16% in Vietnam, 17% in Indonesia, and 27% in Ethiopia. As a share of total tax payments, informal taxes are of the same order of magnitude as subnational taxes in developed countries: in 2001, the OECD average of subnational revenue as a share of total revenue was 21.9% (Isabelle Journard and Per Marhis Kongsrud 2003).

4.1.3 Informal taxes and formal government expenditure

To understand how important informal taxation is to local public finance, we compare informal taxation to government budgets. We focus on Indonesia, where for the 2007 budget year we have data on both district expenditures and village expenditures for the districts and villages in our survey area.13 We convert all amounts to 2000 PPP dollars, and express them in per-household terms. We calculate the mean per-household level of informal taxes and formal taxes from the household survey, as well as the mean per-household level of village and district revenues and village and district expenditures for our sample area; results are given in Table 5.14

Table 5.

Comparison to other local budgets in Indonesia

| Per household value of: | Mean | Informal taxes as percent of…. |

|---|---|---|

| From Indonesia household survey: | ||

| Informal taxes | 49.86 | . |

| Direct formal taxes | 29.16 | 171% |

| Indirect formal taxes | 158.88 | 31% |

| From village budget data: | ||

| Total annual village budget: | 117.64 | 42.4% |

| Village revenue from inter-governmental transfers: | 86.20 | 57.8% |

| Village revenue from local taxes/fees (including informal tax): | 31.44 | 158.6% |

| From district budget data: | ||

| Total annual district budget | 1138.45 | 4.4% |

| Expenditures on salaries: | 474.89 | 10.5% |

| Expenditures on goods & services | 224.70 | 22.2% |

| Capital expenditures: | 396.90 | 12.6% |

| District revenue from central government transfers: | 933.07 | 5.3% |

| District revenue from local formal taxes/fees: | 43.41 | 114.9% |

| District revenue from other sources: | 31.77 | 156.9% |

Notes: All data comes from Indonesia, and all data are for 2007. All are the per-household amounts for the 19 districts where we have complete data from the household survey, the village budget data, and the district budget data. For the village data, the source is the 2008 Census of Villages, matched to the same villages included in the household survey. These district budgets also include the intergovernmental transfers to villages, so these budgets should be viewed as a superset of the village budgets. All amounts are reported in 2000 PPP US$, as in the previous tables, which translates to US$1 = Rp. 3571. Note that districts have budget deficits. Informal taxation payments are not reported in district budgets, so double-counting is not an issue in this comparison. Some amount of informal taxes may be included in “village revenue from local taxes / fees” since this includes some in-kind revenues. Household survey data weighted using household weights.

We find that informal taxes are large relative to village budgets. Average annual per household village budgets are 117.64 dollars per year, whereas our household survey suggests that per household informal taxes are 49.86 dollars per year. The official village budget includes payments in-kind, suggesting that at least some informal taxation is already included in the village budget. The magnitudes demonstrate that informal taxation is one of the primary ways through which local public goods are financed by these villages.

We next compare informal taxation to district budgets. Since Indonesia’s decentralization began in 2001, Indonesian districts have primary responsibility for virtually all local public goods, including local infrastructure, water, health, and education. The budget is divided into expenditures on salaries, goods and services, and capital expenditures.15 These district budgets also include the intergovernmental transfers to villages, so these budgets should be viewed as a superset of the village budgets. Informal taxation payments are 4.4% as large as total district budgets, and 12.6% as large as district spending on capital expenditures. This implies that a non-trivial share of all spending on local public goods occurs through the informal taxation mechanism.

Third, we compare informal taxes with the other taxes that are under the control of local government: formal taxes and fees collected by the village and district governments. Table 5 shows that, other than informal taxation, sources of formal tax revenue under direct control of local governments are limited, as most revenue comes from intergovernmental grants from the national government (which administers the VAT and other taxes). Informal taxes are 1.5 times larger than total village taxes (which likely include at least some “on the books” informal taxation) and 1.15 times as large as total district level formal taxes and fees. Informal taxes are therefore the largest source of finance that is under local control.

The above figures present estimates of informal taxes in which labor payments are monetized as described in the previous section. We have also constructed estimates of informal taxes in which labor payments are monetized using the local unskilled wage rate.16 The resulting estimates of per household informal taxes decline only slightly, from 49.86 to 44.30 dollars per year. This adjustment does not substantively affect any of our conclusions about the importance of informal taxes as a local revenue source.

4.2 Distributional Implications of Informal Taxation

This section examines the distributional implications of informal taxation by looking at the relationship between informal taxation payments and household expenditure. We begin by examining the distribution of informal taxation payments within communities, which tells us how the burden for financing a given level of public goods is borne across high and low income individuals in those communities. Since informal taxation payments are determined at the community level, this within-community analysis is the level of analysis one needs for developing models of informal taxation. We then compare the aggregate burden of informal and formal taxation across the income distribution.

4.2.1 Informal taxation within communities

We first examine the participation margin – i.e., which households make informal taxation payments. Since we are interested in looking within communities, we estimate a fixed-effects logit model of the form

| (1) |

where c is a community, h is a household, αc is a community fixed effect, and PAYhc is a dummy for whether household h in community c made any payments.17 The key coefficient is γ, which is the log odds-ratio of the probability of making payments with respect to log equivalent household expenditure. Given the incidental parameters problem, we estimate (1) as a conditional logit model, which conditions out the αc in estimation. Robust standard errors in this and subsequent regressions are adjusted for clustering at the community level.

The results are presented in Panel A of Table 6. Each cell in the table reports the coefficient on log equivalent household expenditure (γ) from a separate regression of the form in equation (1).18 The estimated overall participation-expenditure gradient is statistically significantly positive in 6 of the 10 countries in our sample and is never negative and statistically significant. The median log-odds ratio among all 10 countries in the sample is 0.19. This demonstrates that the probability of payment is increasing with household expenditure within communities, and this pattern is generally consistent throughout the the countries in our sample.

Table 6.

Informal taxation vs. household expenditure

| Philippines | Albania | Ethiopia | Guatemala | Indonesia | Panama | Nigeria | Vietnam | Nicaragua | Zambia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A:Participation margin, with community fixed effects (conditional logit model) | ||||||||||

| Any payment | 0.035 (0.114) | 0.392*** (0.077) | 0.159 (0.159) | 0.228*** (0.073) | 0.228*** (0.061) | 0.460*** (0.061) | 0.064 (0.048) | 0.407*** (0.048) | -0.075 (0.086) | 0.117*** (0.033) |

| Observations | 2200 | 2487 | 1165 | 5074 | 6188 | 5963 | 9036 | 24521 | 2669 | 10271 |

| Panel B: Total payments, with community fixed effects (Poisson model) | ||||||||||

| Total payments | 0.395* (0.213) | 0.334*** (0.053) | 0.127*** (0.054) | 0.387*** (0.041) | 0.080*** (0.025) | |||||

| Observations | 2143 | 1784 | 1062 | 10840 | 26899 | |||||

| Panel C: Total payments, with community fixed effects, conditional on payments > 0 (Poisson model) | ||||||||||

| Total payments | 0.229* (0.117) | 0.122*** (0.043) | 0.111** (0.049) | 0.364*** (0.041) | 0.001 (0.021) | |||||

| Observations | 655 | 254 | 587 | 9053 | 17310 | |||||

Notes: Each cell reports the estimates from a separate regression, with robust standard errors clustered at the village level in parentheses. Panel A reports results from conditional logit estimates, where the dependent variable is a dummy for making any informal tax payments, the independent variable is log household expenditure per equivalent adult, and the conditioning variable is the village. Panel B reports results from conditional Poisson QMLE models, where the dependent variable is the quantity of informal tax payments (where labor payments are converted to monetary units at the household’s predicted wage rate), the independent variable is log household expenditure per equivalent adult, and the conditioning variable is the village. Panel C reports results from an analogous model to Panel B but without conditioning on the household having made a positive informal tax payment.

Significant at the 10% level;

significant at the 5% level;

significant at the 1% level.

We next examine the relationship between the quantity of payments and expenditure for countries for which data on the quantity of payments are available. Given the large number of observations with no payments, as well as the large number of fixed effects we wish to condition out, we estimate this relationship as a fixed-effects Poisson quasi-MLE regression with robust standard errors (Jerry A. Hausman, Bronwyn H. Hall, and Zvi Griliches 1984; Jeffrey M. Wooldridge 1999; see also Wooldridge 2002). This estimates, by MLE, equations such that

| (2) |

where αc is a community fixed-effect, and PAYMENTMOUNT is the quantity of total payments (in local currency). Given the Poisson QMLE specification, the resulting coefficients χ can be interpreted as elasticities.

To calculate PAYMENTAMOUNT, we monetize labor payments using the imputed average household wage as described above.19 By allowing the wage to vary with household income, we incorporate the fact that providing a day of labor is more costly for those with high opportunity cost.

The results (Table 6, Panel B) show that total payments are increasing in expenditure in all countries for which we have quantity data, and the coefficients are statistically significant in all cases. The estimated elasticities of informal taxation payments with respect to equivalent expenditure are 0.40 in the Philippines, 0.33 in Albania, 0.13 in Ethiopia, 0.39 in Indonesia, and 0.08 in Vietnam. These elasticities are also strictly and statistically significantly less than 1, indicating that while payments increase with expenditure, the share of household expenditures devoted to informal tax payments (i.e., the average tax rate) is declining with expenditure.20 Payments are also increasing in expenditure even conditional on making a positive informal tax payment (Table 6, Panel C), so the overall effects are driven by the intensive margin as well as the extensive margin.21

One might be concerned that measurement error in household expenditure data could cause the estimates to be less than one even if informal taxation is truly progressive. However, applying the classical measurement error attenuation bias formula to our estimates shows that measurement error would have to account for more than 60% of the total variation in observed household expenditures in all countries in order for this to be the case. Moreover, as we show below, we estimate that formal taxes are indeed progressive (with an elasticity > 1). Measurement error, if present, also should not affect our overall conclusions about the relative progressivity of informal and formal taxation, discussed in the next subsection.

Together, the results tell a consistent story: within communities, the wealthy pay more in informal taxes than the poor on an absolute level, though they pay less as a share of their total resources.

4.2.2 Comparing formal and informal taxation

We next compare informal taxes to formal direct and indirect tax payments by households. The results are presented in Table 7. For comparison purposes, Panel A shows the relationship between informal taxes and equivalent household expenditures with community fixed effects and Panel B repeats the same regressions for direct formal taxes.

Table 7.

Formal taxes vs. household expenditure: quantities (H0 : χ=0)

| Philippines | Albania | Ethiopia | Indonesia | Vietnam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Informal taxes, with community fixed effects | |||||

| Total payments | 0.395* (0.213) | 0.334*** (0.053) | 0.127*** (0.054) | 0.387*** (0.041) | 0.080*** (0.025) |

| Observations | 2143 | 1784 | 1062 | 10840 | 26899 |

| Panel B: Direct formal taxes, with community fixed effects | |||||

| Total payments | 1.526*** (0.198) | 1.433*** (0.083) | 0.418*** (0.134) | 1.372*** (0.075) | 0.691*** (0.114) |

| Observations | 2073 | 3358 | 1197 | 11591 | 20407 |

| Panel C: Informal taxes, without community fixed effects | |||||

| Total payments | 0.323* (0.170) | 0.384*** (0.049) | 0.119 (0.112) | 0.438*** (0.035) | -0.156*** (0.049) |

| Observations | 2200 | 2923 | 1062 | 11015 | 28858 |

| Panel D: Direct formal taxes, without community fixed effects | |||||

| Total payments | 1.483*** (0.211) | 1.421*** (0.056) | 0.587** (0.257) | 1.467*** (0.135) | 0.998*** (0.067) |

| Observations | 2259 | 3838 | 1197 | 11674 | 29422 |

Notes: Each cell reports the estimates from a separate regression, with robust standard errors clustered at the village level in parentheses. All results are from conditional Poisson QMLE models, where the dependent variable is given in the table, the independent variable is log household expenditure per equivalent adult, and (in Panels A and B) the conditioning variable is the village. Significance is reported relative to the null hypothesis χ=0.

Significant at the 10% level;

significant at the 5% level;

significant at the 1% level.

The results in Table 7 show that in all countries we examine, the estimated elasticities of formal taxes with respect to household expenditure are greater than the estimated elasticities for informal taxes. For example, the elasticity of formal direct taxes with respect to household consumption is 1.526 in the Philippines, 1.433 in Albania, and 1.372 in Indonesia, so that formal direct taxes are progressive in these countries. By comparison, the analogous elasticity for informal taxes is 0.395 in the Philippines, 0.334 in Albania, and 0.387 in Indonesia, so informal taxes are on average regressive. Note that we use the terms progressive and regressive in reference to the distributional implications of the tax schedules. If informal and formal taxation fund different types of public goods, the distributional consequences of the full tax and expenditure system could differ. However, the difference in progressivity on the revenue side is substantial.

The same overall conclusions hold if we examine income gradients without community fixed effects (Table 7, Panels C and D). The gradients on informal tax payments are between 0 and 1 (with the exception of Vietnam), and the gradients on formal direct tax payments are greater than 1 (with the exceptions of Ethiopia and Vietnam). For all countries, formal direct tax payments are more progressive than informal tax payments.

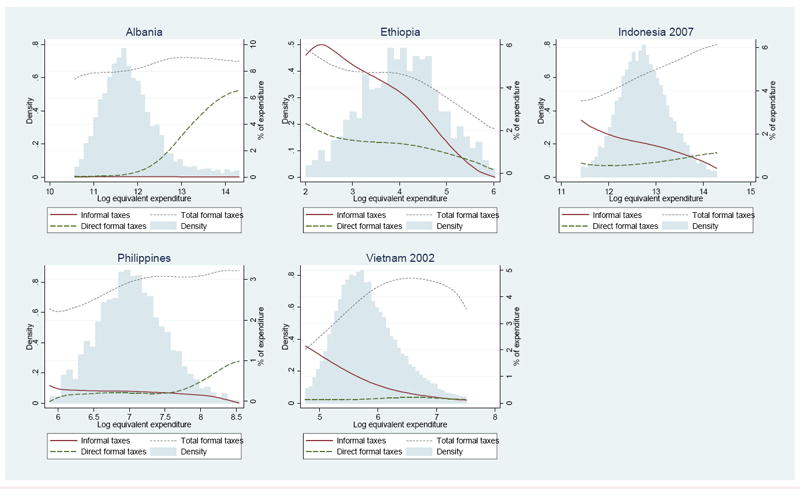

Figure 1 illustrates these differences graphically, plotting informal taxes, direct formal taxes and total formal taxes (i.e., direct + indirect), all expressed as percentages of total household expenditure. In this graph, a proportional relationship (equivalent to a coefficient of 1 in the table) would would correspond to a horizontal line, so a positive slope indicates progressivity (coefficient > 1 in the table) and a negative slope indicate regressivity (coefficient < 1 in the table). For each country, we plot the results of a non-parametric Fan regression (Jianqing Fan 1992) of each variable against log equivalent household expenditure. These regressions do not include community fixed effects, so they are most comparable to Panels C and D of Table 7. The solid lines in Figure 1 show informal taxes, the dashed lines shows direct formal taxes, and the dotted line shows total formal taxes. For comparison, we also plot a histogram of log equivalent household expenditure. To keep the graphs readable, we have excluded the bottom 0.5% and top 0.5% of the household expenditure distribution. The most striking fact about these graphs is that the formal tax system is progressive in most countries whereas the informal tax system is regressive. Including informal taxation therefore makes the total tax burden look more regressive than previously thought, both looking within communities and at the national level.

Figure 1. Comparison of formal and informal taxes as a share of expenditure (without community fixed effects).

Notes: Tax variables are plotted as non-parametric Fan regressions of each variable against log equivalent household expenditure. The y-axis shows tax payments as a share of expenditure; a negative line therefore corresponds to regressivity. These regressions do not include community fixed effects. For comparison, we also plot a histogram of log equivalent household expenditure. To keep the graphs readable, we exclude the bottom 0.5% and top 0.5% of the household expenditure distribution.

4.3 Monetary vs. In-Kind Payments

A notable feature of informal taxation is that payments are often made in labor rather than money (Table 3). To better understand this phenomenon, it is useful to understand in more detail which types of households pay in labor versus money.

To do so, we re-estimate equations (1) and (2) separately for each type of payment, focusing on the countries for which we have data on both monetary and in-kind labor payments. In the quantity analysis, to be consistent with the previous tables, we continue to value labor payments at the household’s predicted average wage rate. Using days instead of monetized labor payments generally makes the reported estimates for labor smaller and accentuates the difference between labor and money more than shown in the tables here.

The results for the participation margin – does the household pay any labor or any money – are presented in Panel A of Table 8, and the results on the quantity paid are presented in Panel B of Table 8. The results in both panels show a very clear pattern: for almost all countries in the sample, monetary payments increase more quickly with overall household expenditure than in-kind labor payments. This is true both on the participation margin and, for the two countries where we have quantity data, on the quantity margin as well. For example, looking within communities in Indonesia, the elasticity of labor payments with respect to household expenditure is 0.26, but the elasticity of monetary payments with respect to household expenditure is 1.45 (see Panel B of Table 8). This implies that monetary contributions are particularly concentrated at higher income levels.

Table 8.

Labor and money payments (H0 : χ =0)

| Indonesia | Panama | Vietnam | Nicaragua | Zambia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Participation margin | |||||

| Labor payment | 0.210*** (0.060) | 0.206** (0.080) | -0.074 (0.066) | -0.071 (0.096) | 0.097*** (0.035) |

| Observations | 6433 | 5782 | 14753 | 2225 | 8902 |

| Money payment | 0.705*** (0.055) | 0.682*** (0.068) | 0.538*** (0.047) | 0.003 (0.121) | 0.128*** (0.049) |

| Observations | 7313 | 5716 | 23780 | 1405 | 6701 |

| Panel B: Quantities | |||||

| Labor payment | 0.260*** (0.039) | -0.018 (0.036) | |||

| Observations | 10840 | 15826 | |||

| Money payment | 1.446*** (0.208) | 0.220*** (0.026) | |||

| Observations | 7632 | 25429 | |||

Notes: See Notes to Table 6. All specifications include community fixed effects. Significance is reported relative to the null hypothesis χ=0.

Significant at the 10% level;

significant at the 5% level;

significant at the 1% level.

4.4 Implications

These stylized facts have several implications for public finance in developing countries. First, a substantial share of households in many developing countries participate in these mechanisms. The results from Indonesia suggest that informal taxation can, at least in some cases, be the largest source of revenue for local communities and may be a non-trivial component of national spending on public capital improvements. Failing to take informal taxation into account will lead to underestimates of the tax burden faced by households, the size of the public sector, and the level of decentralization. Second, informal taxation is redistributive but regressive, and this pattern is observed in almost all of our sample countries. Formal taxes appear to be more progressive than informal taxes, so estimates of formal taxes alone may result in overestimates of the overall progressivity of the tax system. Finally, a notable feature of informal taxation is that in-kind labor payments are an important source of finance and are made even by households with relatively high household expenditure.

These findings also raise a number of questions. Why would communities choose such mechanisms of finance, and why do they tend to be concentrated in developing countries and poor and rural areas? What determines the distribution of payments across individuals within a community, and why do wealthier households pay more than poorer households? Why are in-kind payments so prevalent in informal tax systems when they are rarely seen as part of modern formal tax systems and why labor payments arise in equilibrium. In the next section, we discuss several possible explanations for the patterns observed in the data.

5 Explaining the Stylized Facts

There are a number of (non-mutually exclusive) possible explanations for the observed stylized facts. This section outlines four potential such explanations: informal taxes as a response to explicit legal constraints on formal taxes, informal taxes as an optimal response to information and enforcement problems, informal taxes as user fees, and informal taxation as altruistic voluntary contributions.

5.1 Informal taxation as a response to legal constraints on formal taxes

A first possibility is that informal taxation is simply a response to constraints on the ability of local governments to raise formal taxes to meet their demand for local public goods. Local governments may be legally prohibited by the center from levying certain types of taxes, or capacity problems may prevent them from being able to set up effective systems of formal taxation. If their demand for public goods exceeds intergovernmental transfers, informal taxation may be the only mechanism through which additional public goods can be financed.

This story is consistent with observed instances of informal taxation in the United States, which appear to arise when there are explicit constraints on local ability to raise revenue. When Vermont’s school finance redistribution law made financing schools through higher local taxes more expensive, for example, some communities responded by explicitly pressuring households and businesses to make “voluntary” contributions to schools.22 School fund leaders in Manchester, VT, for example, published lists of compliers and encouraged residents to call or visit non-contributer neighbors.23 Residents described a variety of sanctions levied on non-contributers, ranging from specific punishments (“if there is a restaurant that didn’t pay, I know that I’m not going to eat there”) to more intangible social sanctions (“it’s hard to look at those people in the same way”). Similar extragovernmental mechanisms were observed in California when Proposition 13 limited local property taxes (Eric Brunner and Jon Sonstelie 2003). Labor and money contributions to fire departments, libraries, and recreational services have also been shown to increase in response to fiscal limitations (e.g., James M. Ferris 1984; Douglas C. Bice and William H. Hoyt 2000).

While limits on formal taxes may be important, further explanation is required to explain how informal taxation is sustained or to make predictions about the distribution or form of informal taxation. The remaining explanations suggest these types of testable implications, and help understand now just how informal taxation occurs when it is the only choice, but also suggest when it might be optimal even if formal taxes are feasible.

5.2 Informal taxation as an optimal response to information and enforcement constraints

A second possibility is that informal taxation could in fact arise as the solution to a constrained optimal tax problem. In this framework, outlined in detail in Web Appendix B, local governments wish to finance public goods in a social welfare maximizing way and are making a choice between formal and informal taxation. Communities face an enforcement constraint (punishments for non-compliance may be limited) and a hidden income constraint (high ability types can pretend to be low ability types). We model formal and informal taxation as having different constraint parameters, arising from differences in their tax technologies. In the informal system, enforcement happens through social sanctions rather than through courts. This means that the informal tax system can use information that is observable but not legally verifiable, so informal taxation mechanisms effectively have better information on earnings ability than the formal tax system. On the other hand, by foregoing formal legal proceedings, the informal system must use less severe punishments – i.e., social sanctions instead of jail time – which limits the progressivity of the informal taxation system. The choice between formal and informal taxes therefore represents a trade-off between enforcement and information.

As we show formally in Web Appendix B, informal taxes are likely to be preferred to formal taxes if evasion costs are low or if the community can effectively levy social sanctions. The prevalence of informal taxation throughout our sample of developing countries, particularly in rural areas, is consistent with the existing evidence that informal insurance and credit markets may function more effectively in rural areas, where information is better and villagers are better able to levy informal sanctions for default (Timothy Besley and Stephen Coate 1995; Townsend 1995; Abhijit Banerjee and Andrew Newman 1998; Maitreesh Ghatak 1999) and with existing evidence that local communities have more information about actual income levels than the central government (Harold Alderman 2002; Vivi Alatas et al. 2010). The ability to verify income legally may also be more difficult in developing countries, since many individuals work in or can easily shift into the informal sector. Unsurprisingly, informal taxation mechanisms are not generally observed in developed countries, where it is harder to hide income and where social sanctions may be less effective.

This framework rationalizes the observed positive participation and payment gradients: depending on the distribution of abilities, it may be optimal for the lowest ability types not to participate, and payments should increase with earnings ability. The framework also reconciles the use of in-kind labor payments. In the presence of asymmetric information, labor payments can be used as a screening device, since unobservably high ability types face a higher cost of in-kind labor payments relative to monetary payments.24 While use of labor as a screening device has been considered in the design of income maintenance programs (e.g., Besley and Coate 1992), it has not, to the best of our knowledge, been considered in the context of raising revenue. While it may be optimal for individuals to make payments in labor even if their opportunity cost of time exceeds their marginal value on the project, the highest ability type will always pay in money: the equivalent of the “no distortion at the top” result from the optimal tax literature (James A. Mirrlees 1971).

This story implies that communities may choose to make use of informal taxation as a financing mechanism either when there are exogenous constraints on formal taxation, or when formal taxation is possible, but the information advantages of informal taxation allow a system that is more progressive than would be possible under formal taxation.

5.3 Informal taxation as user fees

A third hypothesis is that these payments represent pre-paid user fees or benefits taxes. A pure user fee model would not necessarily generate a positive correlation between household expenditure and payments unless demand for the goods was correlated with household income. If payments represent benefits taxes, then it is possible that payments could be correlated with income; under Lindahl pricing, for example, each household should pay for the public good according to their marginal benefit (in utility terms).

To examine these hypotheses, we look at whether households are more likely to pay for goods for which they benefit and whether this could explain the observed positive participation gradient of informal tax payments. We focus on the two types of goods for which we can clearly separate users from non-users: we examine whether households who have their own private well are less likely to contribute to water projects, and whether those with school-age children are more likely to contribute to schools.25

For countries for which we have disaggregated data on project type, we do see some mixed evidence of user fees: in some countries, those who are likely to need public water are more likely to pay for water projects and those with children are more likely to pay for schools (Table 9).26 However, with the exception of Zambia, we do not observe a positive expenditure gradient on participation for schools or water projects, even in regressions where we do not control for having children or not having access to private water. This suggests that while these goods may be financed partially through user fees, these goods are not explaining the overall positive correlation we found above between participation rates and household expenditure. The evidence also does not support a Lindahl pricing mechanism for water and schools, unless demand for these goods is inversely correlated with income, which seems unlikely.

Table 9.

User fees

| Indonesia | Nicaragua | Nigeria | Panama | Zambia | Philippines | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: School Contributions | ||||||||||||

| Children in the HH | 0.477** (0.199) | 0.617*** (0.173) | 0.172 (0.113) | 2.106*** (0.228) | 0.827*** (0.112) | 1.094* (0.626) | ||||||

| No private water | -0.117 (0.345) | 0.186 (0.263) | -0.37 (0.359) | 0.464* (0.248) | -0.204 (0.538) | |||||||

| Log expenditure per equivalent adult | 0.348 (0.232) | 0.307 (0.248) | -0.09 (0.122) | -0.137 (0.115) | 0.0246 (0.098) | -0.0107 (0.096) | -0.204** (0.102) | -0.459*** (0.095) | 0.130*** (0.049) | 0.0786* (0.047) | 0.362 (0.362) | 0.284 (0.394) |

| Observations | 1308 | 1308 | 1743 | 1743 | 2860 | 2860 | 4767 | 4767 | 8389 | 8389 | 384 | 384 |

| Panel B: Water Contributions | ||||||||||||

| Children in the HH | 0.319** (0.150) | 0.436 (0.393) | 0.365*** (0.112) | 0.183 (0.167) | -1.077 (1.145) | |||||||

| No private water | 0.122 (0.237) | 3.382*** (0.484) | 1.190* (0.623) | 1.438*** (0.375) | -0.653 (1.032) | |||||||

| Log expenditure per equivalent adult | 0.227 (0.167) | 0.192 (0.165) | -0.167 (0.258) | -0.088 (0.221) | 0.048 (0.135) | 0.004 (0.133) | 0.132 (0.089) | 0.146* (0.082) | -0.191 (2.030) | -0.170 (1.817) | ||

| Observations | 1398 | 1398 | 1076 | 1076 | 3282 | 3282 | 4096 | 4096 | 102 | 102 | ||

Notes: Each column reports results from conditional logit regressions, as in Panel A of Table 6, except the dependent variable is restricted to participation in payments for schools (Panel A) or participation in payments for water systems (Panel B). The first column for each country includes a dummy variable for missing water source. Households were defined as beneficiaries of public water if their listed primary source of drinking water was publicly provided, man-made, and more complex than a simple dug well. Natural sources (river, spring, rain, etc.), public or private dug wells, and other private water sources (piped water, tube wells, etc.) are not counted. Sources such as shared tube/piped wells and community water systems (publicly provided piped water, etc.) are included. Households were defined as beneficiaries of schools if they had at least one member of school age (defined as between ages 4 and 14 years).

Significant at the 10% level;

significant at the 5% level;

significant at the 1% level.

5.4 Informal taxation as altruistic voluntary contributions

Finally, it is possible that these payments are more akin to voluntary charitable contributions than taxes. The range of models of charitable contributions is vast, but it is difficult to reconcile the evidence with a charitable contributions story alone. For example, many of the studies discussed in Section 2 specifically describe the punishments that are imposed on those who do not meet their expected obligations, suggesting that payments are unlikely to be motivated solely by altruism or warm glow preferences (e.g., James Andreoni 1990).

To investigate more systematically the process through which informal tax payments are determined and enforced, we asked both households and village heads in the Indonesia survey to describe who makes decisions regarding household payments and what the consequences are for households who do not participate. The first question we asked was who makes decisions about which households participate in such mechanisms (Table 10). Although respondents were allowed to give multiple responses, only 8% of individual respondents and village heads reported that households make these decisions for themselves; 81% of households report that decisions are made by neighborhood, hamlet, or village heads. We observe a similar pattern when respondents are asked who makes decisions about how much each household is expected to pay: only 20% of households and 15% of village heads report that households make these decisions for themselves. These consistent responses from individual households and from village heads suggest that the these payments are not decided unilaterally by households, but are rather part of a system determined at the community level.

Table 10.

Decisions about informal tax payments

| Respondent | ||

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Village Head | |

| 1. Who makes decisions about which households participate? | ||

| Village/hamlet/neighborhood head | 81.3 | 79.5 |

| Village/hamlet/neighborhood meeting | 38.5 | 54.8 |

| Each household decides for themselves | 8.2 | 8.2 |

| 2. Who determines how much is expected from each household? | ||

| Village/hamlet/neighborhood head | 63.4 | 56.8 |

| Village/hamlet/neighborhood meeting | 40.7 | 61.2 |

| Each household decides for themselves | 20.9 | 15.0 |

| 3. What is the sanction imposed on a household if they do not participate? | ||

| Replace at another time | 10.5 | 12.9 |

| Give materials/food | 11.1 | 20.0 |

| Replace with other person | 5.2 | 9.3 |

| Pay another person to replace you | 2.0 | 5.9 |

| Pay a fine | 16.9 | 21.6 |

| Not allowed to use result of activity | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Excluded from local activities | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| No specified sanction | 63.0 | 54.5 |

| 4. If applicable, who determines this sanction? | ||

| Village/hamlet/neighborhood head | 47.2 | 36.7 |

| Village/hamlet/neighborhood meeting | 47.8 | 61.6 |

| Each household decides for themselves | 22.0 | 20.8 |

Notes: All data comes from Indonesia. Multiple responses were allowed for each question. The full set of choices given for questions 1, 2, and 4 were: village head, hamlet head, neighborhood head, village meeting, hamlet meeting, neighborhood meeting, each household decides for themselves, religious leaders, other informal leaders, and other. For question 4, the choice of no sanction / not applicable was also given. The full set of choices given for question 3 was: replace at another time, give materials/food, replace with another person, pay another person to replace you, pay a fine, not allowed to use result of activity, excluded from local activities, other, and no official sanction.

We then ask respondents about the consequences for not making the determined level of payment. A substantial number of respondents indicated that they would be expected to make up the contribution in another way, either by payment at a different time or in a different form. Most strikingly, 17% of individual respondents and 22% of village heads indicated that non-participating households would be expected to pay a fine. Interestingly, we find that the probability that a household reports a sanction for failure to pay is significantly higher for wealthier households; this could be consistent with poorer households not reporting sanctions because they are not expected to make payments (results not reported in the table). Conditional on some type of sanction being levied, 47% of households stated that the sanction was determined by either the village head or at a village meeting. Charitable contributions motives may be part of what is driving observed payments, but the facts that payment schedules are set by the leader or group, not by the individual, and there are consequences imposed for non-payment suggest that there are other forces at play as well.

Note that use of labor payments is not directly predicted by any of the above stories, with the exception of the optimal constrained tax story discussed in Section 5.2 in which labor payments serve as a screening device. The use of labor payments could also be a response to other types of market failures. If local governments are corrupt, residents may prefer to make payments toward public projects in a form that cannot be expropriated. Another possibility is failures in the labor market, arising from incomplete markets or asymmetric information. If there is excess supply of labor, the opportunity cost of supplying labor may be very low. Local residents may also be more productive than outside hired workers, either because they have better information about how best to implement the project in the local context or because they have less incentive to engage in moral hazard.

Another important point to note when comparing informal tax mechanisms and formal taxation is that the two types of systems may fund different types of public goods. Under the optimal tax model, production may be limited by the ability of community residents since much of the financing is in the form of in-kind labor. In addition, the requirement that communities impose social sanctions may mean that production is limited to goods for which activities are visible, such as construction of public infrastructure. Alternatively, under the user fee model, these mechanisms are only sustainable for goods that are excludable or for which use can be monitored and fees enforced, and under a “warm glow” voluntary contributions model, the choice of public goods may depend heavily on the preferences of those who are motivated to make such contributions.

6 Conclusion

Informal taxation systems appear to play an important role in local public finance in developing countries. We present some of the first systematic, cross-country evidence on the prevalence, magnitude, distributional implications, and forms of informal taxation. We find that informal taxation is prevalent, with 20% or more of households participating in informal taxation schemes in all but one surveyed country, and more than 50% of households participating in several countries. Informal taxes exceed formal direct tax payments by most households and can form a substantial share of households’ total tax burdens. In Indonesia, where we can compare informal taxes to local budgets, we find that informal taxation represents the largest source of public finance under local control and comprises a non-trivial share of all capital expenditures. In all of our sample countries, in-kind payments in the form of labor appear to be an important component of these financing systems, and informal taxation is redistributive but regressive.

Why do these systems arise, and why are they more common in developing countries? One possibility is that they are simply a response to local fiscal constraints: local communities are unable to raise formal taxes to fund their preferred level of public goods, and informal taxation is therefore the only financing mechanism available to them. While this constraint may be important, it does not fully explain the informal taxation phenomenon, since it suggests no direct predictions about the form or distribution of payments. As we have seen, there are in fact systematic patterns that appear to hold across countries. One possibility is that informal taxation reflects the desire of communities to impose more redistributive (socially enforced) tax schedules than are feasible under formal taxation, by taking advantage of local information about income within the community that is observable but not verifiable. Informal taxation may also represent pre-paid user fees, particularly for goods that are excludable. Finally, contributions may be purely voluntary, reflecting “warm glow” in the provision of public goods. In practice, a combination of these forces may be at work.

Regardless of the underlying mechanism(s) at work, our findings have a number of implications for thinking about public finance in developing countries and for development policy. First, a substantial share of households in many developing countries participate in extragovernmental mechanisms for the finance of local public goods. Policies such as the imposition of formal taxes, paid public works programs, and intergovernmental grants may therefore affect households and communities both directly as well as indirectly, through their effects on informal taxation mechanisms. To the best of our knowledge, this type of crowd-out has not traditionally been considered in the analysis of public programs in developing countries.

Second, to the extent that these payments are thought of as a tax, estimates of formal taxes may understate the true tax burden faced by households. In particular, the conventional wisdom that poor households and households in rural areas do not generally pay taxes other than VAT may be misleading. The potential efficiency costs of these taxes have not, to the best of our knowledge, been considered.

Third, failing to take informal taxation into account will lead to underestimates of the size of the public sector and the level of decentralization. In particular, informal taxation can be the dominant source of revenue for local communities and may be a non-trivial component of national spending on public capital improvements in developing countries. While there has been an increasing push toward decentralization in developing countries, such reforms have generally led to greater decentralization of expenditures than of revenue collection (Pranab Bardhan 2002). Since informal taxes are collected at the community level, these findings indicate that a larger share of local public goods is financed locally than the formal budget figures would suggest. In addition, informal taxation generally pays for particular types of goods, so formal tax figures will distort estimates of the mix as well as the level of government expenditures.

Finally, formal taxes appear to be more progressive than informal taxes, so failing to take informal taxation into account will result in overestimates of the overall progressivity of the tax system. The findings also suggest that a marginal expansion of the formal tax system through expansion of the VAT, used to allow communities to reduce informal taxes, could substantially increase the overall progressivity of the tax system. However, it is important to keep in mind that most of these formal taxes are not raised by the local community, and determining the appropriate community-specific intergovernmental transfers is challenging. This is a primary reason why local public goods in developed countries are often financed through local taxation.