Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to present a series of 46 cases of ameloblastoma—38 in mandible and 8 in maxilla treated in the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Government Dental College and Hospital, Nagpur during 1997–2006 with emphasis on various treatment modalities used in treating different types of ameloblastoma and how to define the safe margin for different clinical and histopathological types of ameloblastoma with their follow-up.

Method

Confirmation of lesion done by incisional biopsy upon which treatment plan was decided and if resection is done then section was studied for amount of infiltration in adjoining bone histopathologically.

Result

In a follow-up period of 1–9 years recurrence was observed in six cases, two in patients treated with enucleation and curettage, three in patients treated with segmental resection and one in patient with peripheral ameloblastoma treated with soft tissue resection.

Conclusion

From this study we conclude that depending upon the histopathological type different amount of adjoining bone is resected to get the safe margin and based upon the result it is recommended to remain a bit aggressive in maxillary lesions.

Keywords: Ameloblastoma, Multicystic, Mandible, Malignant, Biopsy

Introduction

As stated by Robinson, ameloblastoma is usually unicentric, nonfunctional, intermittent in growth, anatomically benign and clinically persistent [1]. The tumour is relatively uncommon, it accounts for approximately 1% of all oral tumours [2]. It occurs in all age groups but the lesion is most commonly diagnosed in the third and fourth decades. The tumour shows a marked predilection for the mandible with a preponderance that could be as high as 99.1% [3].

Various reports and articles are present in literature which states various treatment modalities based upon biological behaviour or clinical presentation. This article report the various treatment modalities based upon its clinical and histopathological classification. The various clinical types of ameloblastoma are solid or multicystic type, unicystic type, malignant type and rare peripheral type.

Histopathologically the lesion has been classified as—follicular, acanthomatous, granular, basal, desmoplastic and plexiform.

Out of this, one which requires special attention is desmoplastic ameloblastoma. It has unusual histomorphology with extensive stromal collagenization or desmoplasia [4]. Radiographically it produces mixed radiolucent–radioopaque lesion.

Unlike other types of ameloblastoma, desmoplastic variant present with an ill-defined radiographic margin and look similar to fibro-osseous lesion in half of the cases. The diffuse border also indicate this tumor is more aggressive than other variants of ameloblastoma [5].

The need to separate ameloblastomas is a fundamental concept because of the better prognosis for the unicystic and the peripheral type after limited surgical treatment than it is for the solid type [6].

The multicystic or solid lesion represents the source of the most controversy over surgical management. It is a locally invasive tumour with a high rate of recurrence if not removed adequately but on the other way it has a low tendency to metastasise [6].

Unicystic ameloblastomas generally resemble dentigerous cysts clinically and radiologically although a few are not associated with unerupted teeth. They typically occur more often in younger persons.

The peripheral ameloblastoma is defined as an ameloblastoma that is confined to the gingival or alveolar mucosa. It infiltrates the surrounding tissues, basically the gingival connective tissue but it does not involve the underlying bone [7].

The current trend in surgical treatment of ameloblastoma of the jaws has been either conservative or radical. The conservative approach includes enucleation, curettage or surgical excision with peripheral osteotomy and the radical approach includes resection, where in the mandible it would be either full-thickness resection or resection with preservation of the lower border and in the maxilla it would be defined by the anatomic extension of the excision in partial or total maxillectomy. Enucleation is removal of a lesion from bone with preservation of bone continuity. Curettage is removal of a lesion from bone with preservation of bone continuity by scraping due to absence of an intact encapsulation [6].

The objective of this study is to delineate various types of ameloblastomas histopathologically and treat them in such a way such that minimum amount of bone of normal bone is salvaged to get a clear and safe margin.

Materials and Methods

The data for this report is collected from 46 cases of ameloblastoma treated at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Government Dental College and Hospital, Nagpur between 1997–2006. Out of these, numbers of male patients were 24 and female patients were 22 in number. The age of the patients varied from 11–62 years with average of 31.8 years. The male to female ratio was approximately 1:1.

The diagnosis of the patient was made by clinical and radiological grounds and confirmed by histopathological examination. The protocol for treatment of patient was:

Diagnosis confirmed by incisional biopsy preoperatively.

On the basis of the biopsy report, treatment decided as to go for radical or conservative approach.

Resection performed with a safe margin of 1 cm along the tumor as seen on the radiograph when going for radical treatment.

This sound bone adjoining the tumor sectioned and decalcified.

Sections were prepared in this at 0.25 cm distances.

Histopathological examination was done to check the bony infiltration.

After 6 months reconstruction is done.

Results

From the above study of resection and safe margin the following points that came into light are:

With unicystic ameloblastoma no infiltration was seen in bone in Type I and Type II lesion (Fig. 1). With Type III lesions, infiltration seen within .25 cm of bone margin. In 0.50 cm section of unicystic ameloblastoma no infiltration was seen (Fig. 2).

With follicular and plexiform ameloblastoma infiltration seen upto 0.50 cm of bone margin (Fig. 3). In 0.75 cm section of follicular and plexiform ameloblastoma no infiltration was seen (Fig. 4).

With granular ameloblastoma infiltration seen upto 0.75 cm of bone margin (Figs. 5, 6).

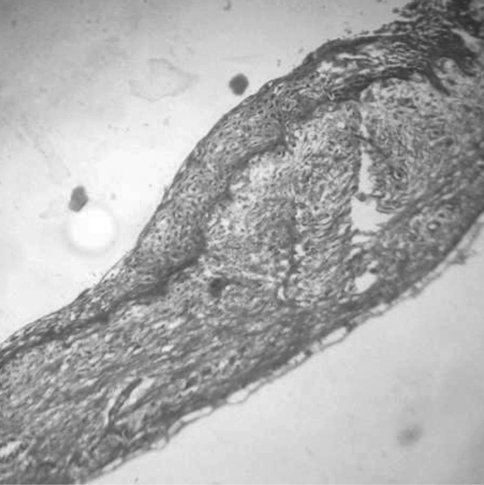

Fig. 1.

Section showing lining in unicystic ameloblastoma (Haematoxylin and Eosin stain ×10)

Fig. 2.

Section showing bone free from infiltration in unicystic ameloblastoma at 0.25 cm margin ameloblastoma (Haematoxylin and Eosin stain ×10)

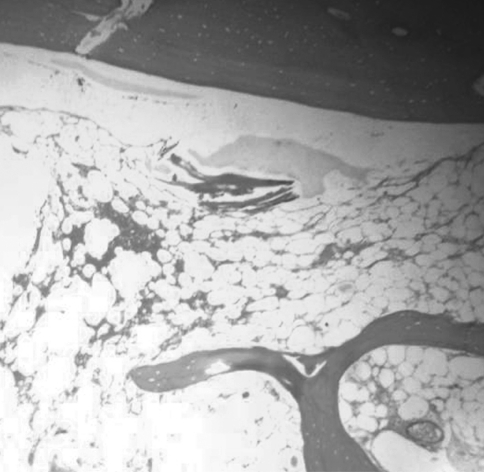

Fig. 3.

Follicular and plexiform ameloblastoma infiltration seen upto 0.50 cm of bone margin

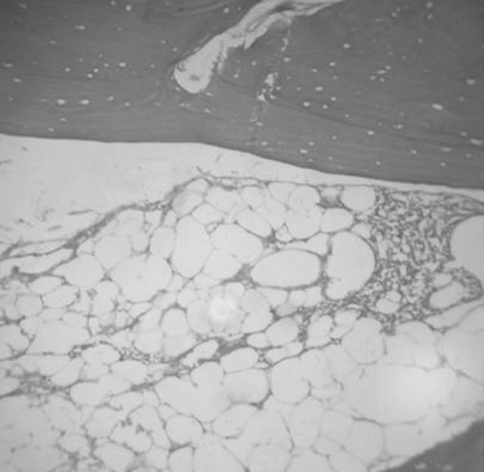

Fig. 4.

Bone margin free from ameloblastic lining in follicular ameloblastoma at 0.75 cm section (Haematoxylin and Eosin stain ×10)

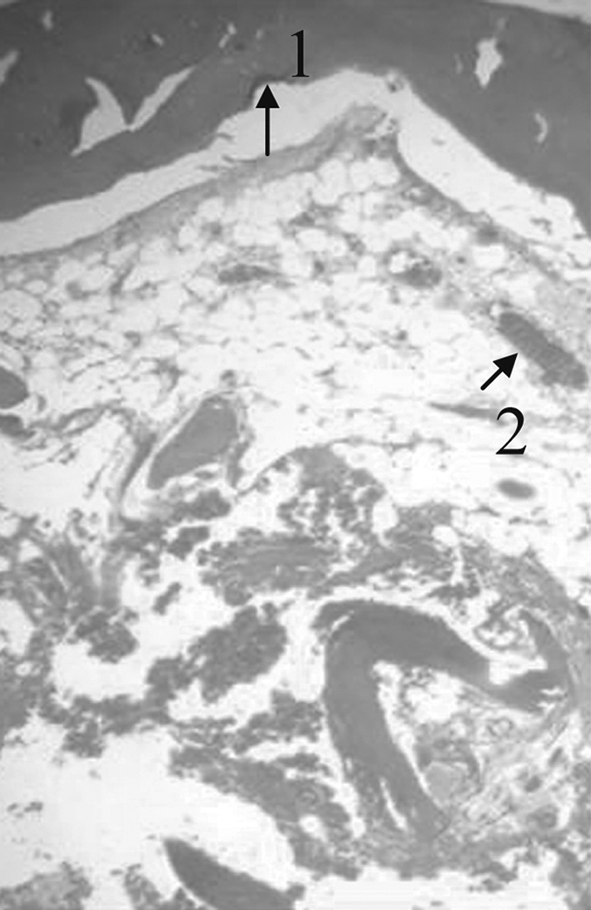

Fig. 5.

Section showing bony infiltration-2 with granular cells-3 and island of ameloblastic follicle-1 (Haematoxylin and Eosin stain ×10)

Fig. 6.

With granular ameloblastoma infiltration seen upto 0.75 cm of bone margin

Discussion

Categorising jaw lesions is difficult. The ameloblastoma falls into the odontogenic tumour group which are tumours derived from epithelial or mesenchymal elements or both that is part of tooth-forming apparatus. They are therefore, found almost exclusively in the mandible and maxilla but according to our study and a report by Minoru and Toshio (1991), they can even be found in the gingival and buccal mucosa on some occasions. Radiologically, they are osteolytic, being usually lucent and frequently multilocular with well defined sclerotic margins which may appear scalloped or expand the cortical plate, tooth roots may move or be resorbed [8].

Approximately 80% of the tumours are found in the mandible [9, 10]. The maxilla is infrequently affected. It occurs in the posterior maxilla in 98% of cases and anterior in 2%. There is early spread to sinus, pterygomaxillary fissure, infratemporal fossa and nasal cavity. There may be intracranial or orbital invasion.

In the present study 82.6% of the lesions were found in the mandible. The molar/ramus area is the most frequently involved in Japanese [11, 12], and Whites [13] more than 70% of the ameloblastomas involve this region. The present study also implicated that the molar/ramus area is the site of greatest predilection, 76.3%. In blacks ameloblastomas occur more frequently in the anterior region of the jaws [13] and reports from Nigeria show that the lesions are frequently gigantic and often cause severe grotesque disfigurement [14], such findings were not noted in this study.

Radical surgery, the treatment recommended for conventional (multicystic) ameloblastoma involves resection of the diseased section of the jaw and inclusion of about 1 or 2 cm of apparently uninvolved bone. In conventional ameloblastoma that has spared the lower border of the mandible, resection of the tumour with the investing dentoalveolar bone and a margin of 1 cm of apparently healthy bone and preservation of the lower border, has been suggested [15, 16]. Whereas others have recommended conservative surgery as a satisfactory approach to treatment of unicystic ameloblastoma [2]. The conservative procedures suggested are broad and vary with different authors. They include surgical techniques such as enucleation, curettage and cauterization.

The effectiveness of the surgical procedure depended upon accessibility of the tumour, the skill of the operator and completeness of removal of the disease. When used alone curettage can be effective in the treatment of some unicystic lesions. Curettage is followed by local recurrence in 90% of mandibular and all maxillary ameloblastomas [17]. A retrospective evaluation of 21 recurrences that included 19 mandibular and 2 maxillary tumours, strongly favoured radical surgery for both primary and recurrent tumours [3].

In our study two cases of unicystic ameloblastoma one mandibular and other maxillary lesions treated primarily by curettage and other by enucleation recurred within 2–4 years. Two cases of maxillary multicystic treated primarily by resection recurred after 3 years. One case of maxillary malignant ameloblastoma showed recurrence within 1 year. One case of peripheral ameloblastoma showed recurrence within 2 years.

Conclusions

Ameloblastoma is a slowly growing tumour. It does not involve vital structures outside the bone, even if it is giant, except if it is disseminated iatrogenically. Recurrences can be seen up to 25 or 30 years after inadequate primary operation Therefore a long follow-up is reasonable in all cases, at least 10 years.

From above histopathological study, we can conclude that:

Type I and II unicystic lesion can be treated by Enucleation and Curettage.

Type III unicystic lesion treated by surgical excision with peripheral osteotomy as it shows infiltration upto 0.25 cm of bony margin.

Multicystic lesion treated depending upon the histopathological type that is if it is follicular or plexiform then resection with safe margin above 0.50 cm and if it is granular then resection with safe margin above 0.75 cm

Desmoplastic lesion treated a bit aggressively with about 1 cm of safe margin.

Peripheral ameloblastoma treated by resecting the soft tissue with safe margin as large as possible keeping adjoining anatomical structure in mind.

Malignant ameloblastoma with safe margin of 1–2 cm followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

One more fact that came into light is maxillary lesions recur more early and needs aggressive treatment even in cases of unicystic ameloblastoma.

Curettage and enucleation can save the patients hospitalization time, function, appearance and life whereas the radical treatment can give the patient lifelong damages to the maxillofacial region so before deciding the treatment plan these facts should be kept in mind. However in this study a long follow period cannot be achieved and need to be done in future study to get a more reliable results.

References

- 1.Shafer (2006) Cysts and tumors of odontogenic origin: textbook of oral pathology, 5th edn. Elsevier Publication, pp 357–432

- 2.Ackermann GL, Altini M, Shear M. The unicystic ameloblastoma: a clinicopathological study of 57 cases. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17(9–10):541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1988.tb01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adekeye EO, Lavery KM. Recurrent ameloblastoma of the maxillo-facial region. Clinical features and treatment. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14(3):153–157. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(86)80282-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reichart PA, Philipsen HA. Desmoplastic ameloblastoma: odontogenic tumors and allied lesions. London: Quintessence Publishing Co Ltd; 2004. pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mintz S, Velez I. Desmoplastic variants of ameloblastoma. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(8):1072–1075. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner DG. Some current concepts on the pathology of ameloblastomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82(6):660–669. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinberg SE, Steinberg B. Surgical management of ameloblastoma. Current status of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81(4):383–388. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minoru U, Toshio K. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy for advanced maxillary ameloblastoma. A case report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991;19(6):272–274. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson HB. Ameloblastoma: a survey of the 379 cases of the literatures. Arch Pathol. 1937;23:831–843. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olaitan AA, Adekeye EO. Unicystic ameloblastoma of the mandible: a long-term follow-up. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55(4):345–348. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(97)90122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueno S, Nakamura S, Mushimoto K, Shirasu R. A clinicopathologic study of ameloblastoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44(5):361–365. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(86)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kameyama Y, Takehana S, Mizohata M, Nonobe K, Hara M, Kawai T, Fukaya M. A clinicopathological study of ameloblastomas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;16(6):706–712. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(87)80057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: biological profile of 3677 cases. Eur J Cancer B. 1995;31B(2):86–99. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akinosi JO, Williams AO. Ameloblastoma in Ibadan, Nigeria. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1969;27(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(69)90181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adekeye EO. Ameloblastoma of the jaws: a survey of 109 Nigerian patients. J Oral Surg. 1980;38(1):36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olaitan AA, Adeola DS, Adekeye EO. Ameloblastoma: clinical features and management of 315 cases from Kaduna, Nigeria. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1993;21(8):351–355. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehdev MK, Huvos AG, Strong EW, Gerold FP, Willis GW. Proceedings: ameloblastoma of maxilla and mandible. Cancer. 1974;33(2):324–333. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197402)33:2<324::AID-CNCR2820330205>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]