Abstract

Pleomorphic adenoma is the benign tumor of salivary glands, which originates from the myoepithelial cells and intercalated duct cells. This tumor is more common in major salivary glands. This case report describes a rare and unusual lesion in a 55-year-old female, which was diagnosed as pleomorphic adenoma of the minor salivary glands in the upper lip. The tumor was a circumscribed, submucosal nodule, about 2.0 cm in diameter and was characterized by slow growth and rubbery consistency. Complete excision was performed and the histopathological analysis showed an epithelial salivary gland tumor with islands of plasmacytoid cells, duct like structures, in a variable stroma with chondroid, fibrous and myxoid appearance. No recurrence was observed 1 year after the surgery.

Keywords: Minor salivary glands, Pleomorphic adenoma, Upper lip

Introduction

Salivary gland tumours account for less than 3% of the head and neck tumours [1]. They are more common in adults than in children [2, 3]. Tumours arising in the minor salivary glands account for 22% of all salivary gland neoplasms [4]. The majority are malignant; only 18% are benign. The most common site of a Pleomorphic Adenoma (PA) of the minor salivary glands is the palate, followed by lip, buccal mucosa, floor of mouth, tongue, tonsil, pharynx, retromolar area and nasal cavity [4–7]. Approximately 85% of all PA are located in the parotid glands, 10% in the minor salivary glands, and 5% in the submandibular glands [8]. When they originate in the minor salivary glands, they occur mostly in the hard palate and soft palate. The second most common site of origin is the upper lip [9]. PA is more often seen in women in the fourth to sixth decade of their life, and has a natural history of asymptomatic slow growth over a long period [10]. The etiology of PA is unknown. It is of epithelial origin and clonal chromosome abnormalities with aberrations involving 8q12 and 12q15 have been described [10]. Histologically, PA is characterized by a large variety of tissues consisting of epithelial cells arranged in a cord-like cell pattern, together with areas of squamous differentiation or with plasmacytoid appearance [10]. Myoepithelial cells are responsible for the production of abundant, extracellular matrix with chondroid, collagenous, mucoid, and osseous stroma [10].

Case Report

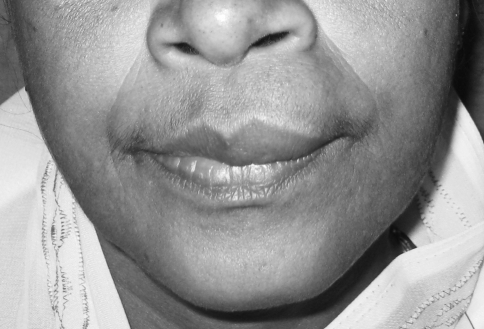

A 55-year-old female came to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery with a submucosal nodule in the maxillary left labial mucosa (Fig. 1). She had first noted the lesion about 1 year ago, after which it had gradually increased in size. The clinical development of the nodule was slow and asymptomatic. On examination the nodule was circumscribed, mobile, sessile, and rubbery in consistency and 1.5 to 2 cm in diameter (Fig. 2). The overlying mucosa was smooth with a pinkish color showing evidence of superficial vascularity. There was no pain or bleeding on palpation. There was no evidence of the lesion on the external surface of the lip. Medical history was unremarkable, and no other abnormalities were found on clinical examination.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative frontal view

Fig. 2.

Oval swelling of the upper lip

A dental etiology was ruled out based on clinical and radiological examination. Thus, the clinical diagnosis established was compatible with a benign salivary gland tumour or a lipoma.

The tumour was completely removed along with extraction of mobile 22 and other root stumps. As the specimen was completely encapsulated, the lesion was excised without any difficulty with clinically normal margin (Figs. 3, 4, 5). Subsequent follow-up after 1 year showed no sign of recurrence (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

Blunt dissection of the encapsulated mass

Fig. 4.

Specimen intact

Fig. 5.

Primary suturing

Fig. 6.

Postoperative view

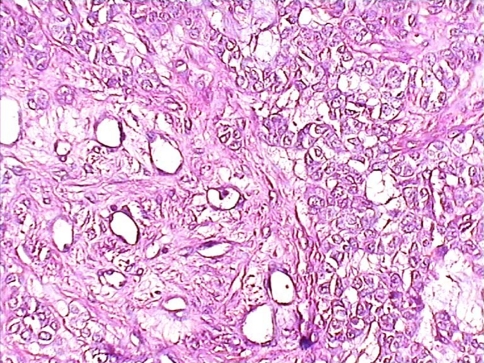

Histopathological analysis of the surgical specimen revealed a cellular mass in a variable stroma with chondroid, fibrous and myxoid appearance. There was no evidence of malignancy. The diagnosis was PA (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Histopathology of pleomorphic adenoma of minor salivary gland

Discussion

PA is slow growing, well demarked, and usually encountered in the parotid gland. Histologically, there is morphologic diversity, including mucoid, chondroid, osseous, and myxoid elements [11].

The myoepethelial cell is thought the cell of origin capable of producing such a variety of characteristic importance there are both visible excrescences and microscopic prolongation that account for the high recurrence rate if enucleation alone is performed [11].

Differential diagnosis of intraoral solid, asymptomatic nodules include, minor salivary gland tumours and benign and malignant mesenchymal lesions such as neurofibroma and rhabdomyosarcoma. For differential diagnosis of lesions affecting the buccal mucosa, lip and tongue, lipoma, neurofibroma and other benign mesenchymal tumour should be considered. The encapsulation and mobility of the nodule are the signs of benignity, although a biopsy must always be performed [12].

PA are usually painless, slow growing tumours, however, some cases exhibiting rapid growth have been reported, especially in the palate. PA appears to be encapsulated, but this capsule is often infiltrated by lateral extension of the tumour. Even though PA is benign, it has a high rate of implantability. Any rupture of the capsule or incomplete excision will leave residual tumour cells behind, resulting in recurrence [13].

In a retrospective study, McGregor et al. showed that of 31 patients under 30 years of treatment for PA, 42% (n = 16) developed recurrence. All recurrences occurred in parotid gland. All authors believed that the chances of recurrence are higher when the first incidence of PA appears before 30 years of age [14, 15].

A lesion referred to as Salivary Gland Anlage Tumour (SGAT) histologically resembles a PA [16, 17]. The microscopic and ultrastructural pattern of this benign tumour shows epithelial and mesenchymal components, with tubular and cord like structures composed of cells immunophenotypically compatible with myoepithelium, which expresses a broad spectrum of keratins and epithelial membrane antigens while the stromal component expresses vimentin and smooth muscle actin [18, 19]. Only 23 cases have been described in the literature so far, and the studies comparing the nature of the epithelia, myoepithelial cells and stromal components of the SGAT with those of the PA are lacking. It is known that the luminal cells of PA are positive for cytokeratin and S-100 protein and negative for vimentin, and that the myoepithelial cell markers are vimentin, alpha-smooth- muscle actin or calponin. This difference may be related to the cellular differentiation of both entities. However, the SGAT is seen as a nasal or nasopharyngeal obstruction in the newborns, especially males, and there have been no reported recurrences [20]. Thus, it has been proposed that it may have a hamartomatous nature, its histological resemblance with PA, makes it a true benign salivary gland tumour.

The present case did not show any local recurrence 12 months after surgery. However taking into consideration the characteristics of salivary gland neoplasms, which may recur after many years, patient will be followed up at least 5 years.

As these lesions are asymptomatic, the patient may not be aware of their existence or are discovered accidentally by a dentist during examination.

Acknowledgement

I wish to thank Dr Pascal X. Pinto, MDS, FDSRCS, Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, KIDS Belgaum, for his support and guidance in preparing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Luna MA, Batsakis JG, el-Naggar AK. Salivary gland tumours in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100(10):869–871. doi: 10.1177/000348949110001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley P, McClelland L, Mehta D. Paediatric salivary gland epithelial neoplasms. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2007;69(3):137–145. doi: 10.1159/000099222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaaban H, Bruce J, Davenport PJ. Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the palate in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54(3):245–247. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2000.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiro RH. Salivary neoplasms: overview of a 35-year experience with 2,807 patients. Head Neck Surg. 1986;8(3):177–184. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890080309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldron CA, el-Mofty SK, Gnepp DR. Tumours of the intraoral minor salivary glands: a demographic and histologic study of 426 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66(3):323–333. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90240-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eveson JW, Cawson RA. Tumours of the minor (oropharyngeal) salivary glands: a demographic study of 336 cases. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14(6):500–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1985.tb00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MA. Pleomorphic adenoma of the cheek. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;15(6):777–779. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(86)80123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey BJ (2001) Head and neck surgery. In: Otolaryngology, chap 107, 3rd edn. Lippincott Williams and wilkins, Philadelphia

- 9.Ballenger JJ (2003) Head and neck surgery. In: Otolaryngology, vol 2, chaps 50, 54, 62, 16th edn. BC Decker Inc., Spain

- 10.Forty MJ, Wake MJ. Pleomorphic salivary adenoma in an adolescent. Br Dent J. 2000;188(10):545–546. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800534a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berjis N, Haji Malian M (2006) Pleomorphic adenoma presented as a subglotic mass. 7. http://semj.sums.ac.ir.

- 12.Jorge J, Pires FR, Alves FA, Perez DE, Kowalski LP, Lopes MA, Almeila OP. Juvenile intraoral pleomorphic adenoma: report of five cases and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31(3):273–275. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniels JS, Ali I, Al Bakri IM, Sumangala B. Pleomorphic adenoma of the palate in children and adolescents: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(3):541–549. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGregor AD, Burgoyne M, Tan KC. Recurrent pleomorphic salivary adenoma—the relevance of age at first presentation. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41(2):177–181. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(88)90048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellies M, Schaffranietz F, Arglebe C, Laskawi R. Tumours of the salivary glands in childhood and adolescence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(7):1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Har-El G, Zirkin HY, Tovi F, Sidi J. Congenital pleomorphic adenoma of the nasopharynx (report of a case) J Laryngol Otol. 1985;99(12):1281–1287. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100098546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dehner LP, Valbuena L, Perez-Atayde A, Reddick RL, Askin FB, Rosai J. Salivary gland anlage tumour (“congenital pleomorphic adenoma”). A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of nine cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(1):25–36. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrmann BW, Dehner LP, Lieu JE. Congenital salivary gland anlage tumour: a case series and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(2):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen EG, Yoder M, Thomas RM, Salerno D, Isaacson G. Congenital salivary gland anlage tumour of the nasopharynx. Pediatrics. 2003;112(1 Pt 1):e66–69. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.1.e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furuse C, Sousa SO, Nunes FD, Magalhães MH, Araújo VC. Myoepithelial cell markers in salivary gland neoplasms. Int J Surg Pathol. 2005;13(1):57–65. doi: 10.1177/106689690501300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]