Abstract

Background

With the advancements in dentistry the treatments are done with high perfections and patient comfort. Noninvasive, methods reduce fear and anxiety of the patient on phobia of syringes and injections. Topical anesthesia satisfies all the above criteria.

Aim and objective

Comparison of the efficacy of topical application of lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel and bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel for extraction of teeth.

Materials and methods

Lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel and bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel are prepared with carbopol (thickening agent). 510 extractions with lignocaine hydrochloride gel 5% and bupivacaine hydrochloride gel 5% in equal numbers was undertaken. Parameters of onset of anesthesia, peak effects, pain, and disappearance of numbness, local irritation, bleeding and periodontal status of teeth to be extracted were taken into consideration.

Results

Onset and peak effect were faster with 5% lignocaine hydrochloride gel. 5% bupivacaine hydrochloride gel had longer duration of analgesia. Patients experienced more pain with bupivacaine. Grade 1 mobile posterior teeth were painful during extraction.

Conclusion

5% lignocaine hydrochloride gel is better than 5% bupivacaine hydrochloride gel as a topical anesthetic for extraction of grade II and grade III mobile teeth.

Keywords: Topical anesthesia, Lignocaine hydrochloride, Bupivacaine hydrochloride

Introduction

Pain is the cynosure of all basic and clinical sciences [1]. Relief of pain should be the objective of every phase of the healing arts. Success usually depends on relieving the pain and administering treatment with least amount of trauma. Many children and indeed adults are afraid of syringes and needle insertions. This fear and anxiety overpowers any rational thinking. So the challenge faced by the clinician, is to provide an environment that allows treatment to be delivered without inflicting any adverse psychological trauma or physical harm. Topical anesthesia satisfied all the above criteria. However, depth of penetration has been a limiting factor to its widespread use. It has been used for minor surgical procedures such as removal of arch bars, gingivectomy, subgingival scaling, orthodontic band placement, gingival curettage, needle insertions and pain relief from acute infections, inflammatory conditions, ulcerations, wounds and extraction of periodontally weak teeth.

These topical gels have an advantage of locally targeting the drug, better control over systemic drug absorption, offering a greater bio-availability and reduction in dosage.

Lignocaine base and lidocaine hydrochloride have efficient pain control with short duration for the above purposes. So it was decided to try a long acting topical anesthetic for securing analgesia with increased duration for extraction of teeth. As bupivacaine is one of the most successful long acting local anesthetic, it was thought to use this as the topical anesthetic (in concentration of 5%) in comparison with lignocaine 5% gel (Fig. 1).

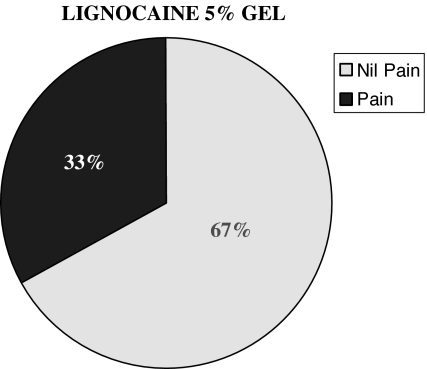

Fig. 1.

Lignocaine 5% gel efficiency in controlling pain

To make the study symmetrically comparable, both the drugs are mixed with carbopol in same concentrations. Lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel was obtained in a solution form (uniform mix) but bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel was obtained in a dispersed form (Fig. 2).

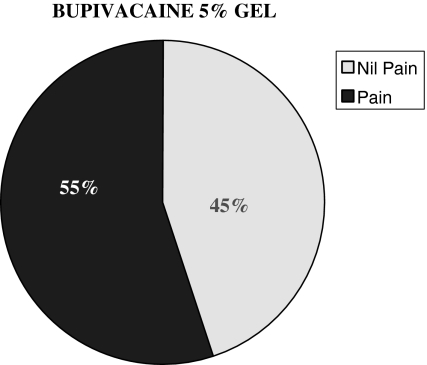

Fig. 2.

Bupivacaine 5% gel efficiency in controlling pain

No study has been published so far which has dealt with the use of topical anesthetics as the sole means of anesthesia for extractions. An attempt has been made to fill this void.

In our study we have used the most commonly performed minor surgical procedure i.e. extraction and observed onset of anesthesia, peak effect, pain during extraction and duration of analgesia. Local complications, bleeding, surrounding soft tissue anesthesia and taste alteration were also observed (Figs. 3, 4, and 5).

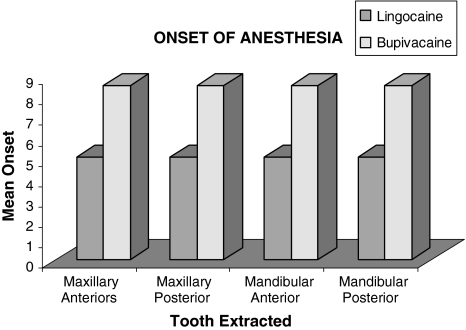

Fig. 3.

Onset of anesthesia in the study population by the type of local anesthesia used

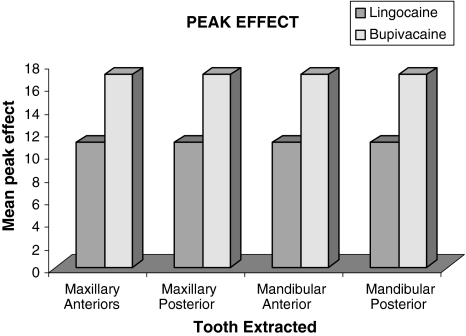

Fig. 4.

Peak effect in the study population by the type of local anesthesia used

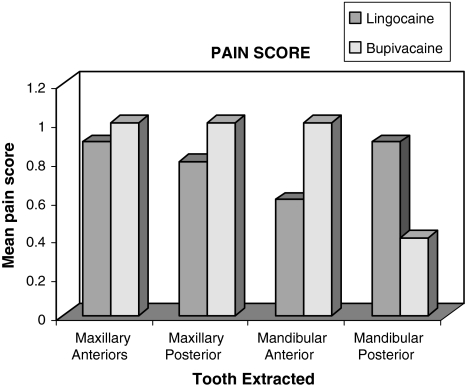

Fig. 5.

Pain score in the study population by the type of local anesthesia used

Before the start of the study, protocol was made and ethical clearance was obtained from the committee constituted by the Institute (PMNM Dental College, Bagalkot).

Each and every patient was made aware of the study protocol and was asked to sign the informed consent written in local language for their understanding.

Materials and Methods

A clinical study of 510 extractions with lignocaine hydrochloride gel 5% and bupivacaine hydrochloride gel 5% in equal numbers was undertaken. Patients requiring dental extractions referred to the department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, P.M. Nadagouda Memorial Dental College and Hospital, Bagalkot, were selected.

Pilot Study

Pilot study was conducted with the above gels, and it was found that the gels were ineffective to secure analgesia for firm teeth.

Inclusion Criteria

Healthy adult patients with age groups of 12 to 80 years requiring extraction of periodontally weak teeth irrespective of the grades of mobility.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients allergic to lignocaine and/or bupivacaine, severe periapical infections, systemic conditions contraindicating extraction and adverse drug interactions of lignocaine and/or bupivacaine with any drugs taken by the patient, no analgesics for the past 24 h, and not on any anti-hypertensive, antiepileptic, muscle relaxants and antipsychotic drugs.

Parameters Measured/Evaluated

Parameters of onset of anesthesia, peak effect, pain, and disappearance of numbness, local irritation, bleeding and periodontal status of teeth to be extracted were taken into consideration.

Method of Preparation

The preparation of gel was done at college of pharmacy, Mahe. Every month, gel used to be prepared freshly and transported to our head of the department. The following formula was used for the preparation of both the gels.

Formula

| Carbopol | 1 g |

| Lignocaine hydrochloride | 5 g |

| Distilled water | 100 ml |

| Triethnolamine PH | 7–7.2 |

After the preparation of both the gels, double blinding was done with patients (subjective) and observer being blind to eliminate bias.

Procedure

A thin layer (approximately 2 to 5 mm thickness) of the gel is applied on the dried gingival (attached and free) and alveolar mucosa of the concerned teeth on the buccal/labial and lingual/palatal mucosa up to the level of the tip of the root.

Onset is measured by probing the gingival (free or attached) and alveolar mucosa every minute. The other objective symptoms such as superficial probing, deep probing and gingival detachment were assessed with a sharp probe or sharp end of the periosteal elevator.

All the patients were asked to rate the pain verbally (verbal scale) as: 0—nil; 1—mild; 2—moderate; 3—severe.

The time period from the application of gel to the detachment of the gingiva painlessly was taken as peak effect.

An intraoral pressure pack was placed over the extraction site after the extraction. This pack was removed after 10 minutes and the socket was checked for bleeding, if any bleeding was noticed after 10 minutes, it was considered as excessive bleeding.

After extraction, the patients were checked periodically to note the time taken for termination of numbness by either asking the patient verbally about pain in the socket or by probing the gingiva every 10 minutes without disturbing the pressure pack.

The site of application was noted for any ulceration or inflammation (local complications) after extraction. Patients were also monitored for excessive salivation, taste and anesthesia of surrounding tissue.

Results and Observations

510 extractions of periodontally weak teeth were done by either topical application of lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel or bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel in equal numbers.

The total number of extraction done of grade I, II and III mobile teeth with 5% lignocaine hydrochloride gel were 29(11.3%), 83(32.5%) and 14(56.2%) respectively.

The total number of extractions done of grade I, II and III mobile teeth with 5% bupivacaine hydrochloride gel were 26(10.2%), 92(36.1%) and 138(54.1%) respectively.

The number of extractions which could not be done due to ineffective anesthesia was 9 out of 255(4%) for 5% lignocaine hydrochloride gel and 8 out of 255(3.5%) for 5% bupivacaine hydrochloride gel.

The onset of analgesia was quicker with lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel than bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel irrespective of the position and mobility of the tooth to be extracted (Table 1).

Peak effect was achieved faster with lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel than bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel (Table 2).

Table 1.

Onset of analgesia (min) of the study group of LA

| Tooth and mobility | Lignocaine (5%) (I) | Bupivacaine (5%) (II) | t-Value | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | No. | Mean | SD | |||

| Maxillary anterior grade I | 9 | 4.67 | 0.87 | 10 | 9.30 | 1.89 | 6.73 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary anterior grade II | 27 | 4.44 | 1.12 | 26 | 8.46 | 1.50 | 11.06 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary anterior grade III | 45 | 4.13 | 0.81 | 34 | 7.97 | 2.29 | 8.69 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary posterior grade I | 4 | 4.00 | 0.82 | 3 | 7.33 | 2.31 | – | – |

| Maxillary posterior grade II | 18 | 4.28 | 0.96 | 10 | 9.70 | 3.23 | 6.78 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary posterior grade III | 22 | 4.55 | 0.80 | 23 | 8.26 | 1.96 | 8.19 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade I | 15 | 4.27 | 1.22 | 10 | 9.60 | 1.84 | 8.72 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade II | 23 | 4.48 | 1.27 | 34 | 9.38 | 2.74 | 8.25 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade III | 44 | 4.43 | 0.97 | 44 | 7.91 | 2.64 | 8.33 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular posterior grade I | 1 | 4.00 | – | 3 | 7.33 | 2.31 | – | – |

| Mandibular posterior grade II | 15 | 4.73 | 1.62 | 22 | 9.05 | 2.32 | 6.32 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular posterior grade III | 32 | 3.97 | 0.82 | 37 | 8.95 | 2.21 | 12.13 | <0.001 |

Student’s t-test (unpaired)

P < 0.001 HS

Table 2.

Peak effect (min) of the study group of LA

| Tooth and mobility | Lignocaine (5%) (I) | Bupivacaine (5%) (II) | t-Value | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | No. | Mean | SD | |||

| Maxillary anterior grade I | 9 | 9.89 | 1.05 | 10 | 16.00 | 2.21 | <.54 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary anterior grade II | 27 | 9.41 | 1.58 | 26 | 15.65 | 2.43 | 11.14 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary anterior grade III | 45 | 9.33 | 1.98 | 34 | 15.68 | 2.91 | 11.53 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary posterior grade I | 4 | 10.25 | 1.50 | 3 | 16.33 | 4.04 | – | – |

| Maxillary posterior grade II | 18 | 9.50 | 2.57 | 10 | 16.30 | 2.91 | 6.40 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary posterior grade III | 22 | 10.09 | 1.11 | 23 | 16.52 | 3.85 | 7.54 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade I | 15 | 9.60 | 0.99 | 10 | 17.40 | 3.17 | 8.98 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade II | 23 | 10.09 | 1.62 | 34 | 16.29 | 2.93 | 9.23 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade III | 44 | 9.91 | 1.48 | 44 | 15.84 | 2.91 | 12.06 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular posterior grade I | 1 | 8.00 | – | 3 | 16.33 | 2.52 | – | – |

| Mandibular posterior grade II | 15 | 9.53 | 2.20 | 22 | 16.45 | 3.19 | 7.29 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular posterior grade III | 32 | 9.41 | 1.50 | 37 | 16.41 | 2.80 | 12.64 | <0.001 |

Student’s t-test (unpaired)

P < 0.001 HS

Verbal Pain Score

It was found that for maxillary anterior grade I mobile teeth, pain experienced was more with bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel than lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel. But for grade II mobile teeth, pain experienced was more for lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel than bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel (Table 3).

For maxillary posterior grade I mobile teeth, pain experienced was more with bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel than lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel.

For mandibular anterior grade I, II and III mobile teeth, pain experienced was comparatively more with bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel than lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel.

Extraction was not possible with bupivacaine hydrochloride 5% gel for grade I mandibular posterior teeth. But with lignocaine hydrochloride 5% gel, 2 teeth were extracted.

170/246 (66.6%) showed 0 (nil) score, 50/246 (19.60%) showed 1 (mild), 24/246 (11.76%) scored 2 (moderate) and 2/246 (1.96%) scored 3 (severe) with lignocaine 5% gel.

141/247 (55.29%) showed 0 (nil) score, 63/247 (24.70%) showed 1 (mild), 35/247 (15.29%) scored 2 (moderate) and 8/247 (4.7%) scored 3 (severe) with bupivacaine 5% gel.

Table 3.

Pain score (min) of the study group of LA

| Tooth and mobility | Lignocaine (5%) (I) | Bupivacaine (5%) (II) | t-Value | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | No. | Mean | SD | |||

| Maxillary anterior grade I | 9 | 1.22 | 0.67 | 10 | 2.00 | 2.16 | 1.03 | 0.31 NS |

| Maxillary anterior grade II | 27 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 26 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 1.47 | 0.15 NS |

| Maxillary anterior grade III | 45 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 34 | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.75 NS |

| Maxillary posterior grade I | 4 | 1.50 | 0.58 | 3 | 2.00 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Maxillary posterior grade II | 18 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 10 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.54 NS |

| Maxillary posterior grade III | 22 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 23 | 0.43 | 0.84 | 1.54 | 0.13 NS |

| Mandibular anterior grade I | 15 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 10 | 1.89 | 1.23 | 2.29 | 0.03 NS |

| Mandibular anterior grade II | 23 | 0.52 | 0.73 | 34 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 1.77 | 0.08 NS |

| Mandibular anterior grade III | 44 | 0.25 | 0.53 | 44 | 0.73 | 1.58 | 2.12 | 0.04 NS |

| Mandibular posterior grade I | 1 | 2.00 | – | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| Mandibular posterior grade II | 15 | 0.40 | 0.74 | 22 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 1.79 | 0.07 NS |

| Mandibular posterior grade III | 32 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 37 | 0.35 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 0.66 NS |

Student’s t-test (unpaired)

P < 0.001 HS

Overall the percentage of nil pain in lignocaine group were 67% (170/255), with pain were 33% (85/255) and in bupivacaine group were 45% (141/255) and 55% (114/255) with pain, with most of the patients following in the mild pain group.

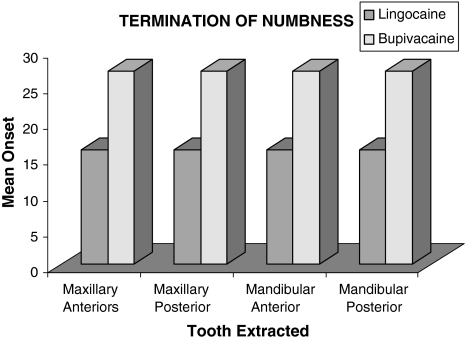

Termination of numbness was quicker with lignocaine 5% gel than bupivacaine 5% gel (Fig. 6; Table 4).

In grade I maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth, it was observed that extraction of canine was most painful may be because inadequate anesthesia due to thick palatal mucosa in the maxillary region and loss of gel by salivation in the lingual side for the mandibular region and also may be of its longer root length.

There was no local irritation or systemic toxic reaction with any one of the patients. All the patients reported a bitter taste of both gels. Bleeding and salivation was normal for all the patients. Surrounding soft tissue analgesia was observed when gel accidentally came in contact with the oral mucosa and lasted for a longer period than the hard tissue analgesia.

Fig. 6.

Termination of numbness in the study of pain

Table 4.

Termination of numbness

| Tooth and mobility | Lignocaine (5%) (I) | Bupivacaine (5%) (II) | t-Value | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | SD | No. | Mean | SD | |||

| Maxillary anterior grade I | 9 | 15.33 | 1.80 | 10 | 28.40 | 3.66 | 9.69 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary anterior grade II | 27 | 16.19 | 3.61 | 26 | 29.46 | 4.46 | 11.94 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary anterior grade III | 45 | 16.64 | 2.36 | 34 | 29.32 | 3.77 | 18.33 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary posterior grade I | 4 | 17.25 | 3.10 | 3 | 30.00 | 5.29 | – | – |

| Maxillary posterior grade II | 18 | 16.33 | 3.34 | 10 | 28.70 | 2.31 | 10.16 | <0.001 |

| Maxillary posterior grade III | 22 | 17.77 | 3.02 | 23 | 29.57 | 3.15 | 12.81 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade I | 15 | 17.07 | 3.03 | 10 | 28.80 | 2.74 | 9.83 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade II | 23 | 17.52 | 3.29 | 34 | 29.74 | 3.24 | 13.88 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular anterior grade III | 44 | 16.52 | 2.47 | 44 | 29.14 | 3.72 | 18.37 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular posterior grade I | 1 | 23.00 | – | 3 | 30.67 | 1.15 | – | – |

| Mandibular posterior grade II | 15 | 17.53 | 3.14 | 22 | 29.87 | 3.83 | 8.98 | <0.001 |

| Mandibular posterior grade III | 32 | 16.91 | 2.22 | 37 | 29.32 | 3.67 | 16.68 | <0.001 |

Student’s t-test (unpaired)

P < 0.001 HS

Discussion

Topical anesthesia has been in use for different procedures such as topical bupivacaine and etidocaine following fallopian tube banding [2], in manipulation of fractured nose by amethocaine gel [3], lignocaine gel for cystoscopy in men [4], pain control following simple dental extractions by topical bupivacaine [5], gingival mucosal anesthesia by lignocaine 10% spray or 5% eutectic mixture, painless removal of arch bars by EMLA cream [6], for topical anesthesia in periodontal manipulations, operative density and mirror oral surgical procedures [7].

However, there has been no scientific study on topical anesthesia for extraction of teeth in adults. The most commonly used topical anesthetic in anesthesia is lignocaine 5% as a pre-injection procedure to make the needle insertion painless. A variety of drugs in the form of sprays, gels, ointments and creams are in use. Topical anesthesia is also used to control post-extraction pain [8, 9] fallopian tube banding [10] etc.

To enable us to achieve satisfactory anesthesia and to totally eliminate pain during extraction, a concentration of 5% lignocaine and 5% bupivacaine which are the most commonly available local anesthetic agents in solution form in our country were thought to be suitable for our study.

The most common form of topical anesthesia i.e. ointment has the disadvantage [10] of shorter retention time of the drug at the application site, as it leaches out into the oral cavity shortly after application mainly because of its low viscosity. Ultimately, a very short clinically insignificant pain relief [10] is obtained following topical application.

To overcome this problem of retaining the drug on the mucosa for a desired length of time, and to achieve adequate anesthesia [11], 5% lignocaine and bupivacaine gels were made with carbopol [12] which increases the mucoadhesion and helps in the stability of the mixture for longer period of time.

Creams, ointment [10], 5% eutectic mixtures [6, 13], patches [10], cellulose discs [10], sprays [13] have been used as different modes of topical anesthesia. These studies of using discs, patches etc. indicate advantage over other modes since they retain the drug for longer periods at the desired site. However, the facility to manufacture these drugs in the form of patches or discs etc. is not easily available and increases the cost of treatment phenomenally. Therefore it was decided to prepare 5% gel with carbopol which is an acrylic acid polymer used as a thickening agent and has an inherent property of swelling when it comes in contact with aqueous fluids leading to interpenetration in the pores of mucous membrane thereby giving increase in retention time of the drug at the site.

Cotton pads [10] as carrier during the application procedure have proved inadequate to achieve adequate analgesia. Therefore the drug is directly applied to the alveolar mucosa and gingival of buccal/labial, palatal, lingual surface of the indicated teeth.

Bupivacaine was proved to be a drug of choice in comparison with lignocaine because it provided good topical analgesia when used in transurethral resection of benign prostatic hyperplasia [14] delivering a mean duration of 141 min compared to 29 min of lignocaine and also has been used as topical anesthesia in children who underwent multiple extractions [2] under general anesthesia to reduce post extraction pain.

Many studies have indicated that onset of anesthesia to be within 5 min for applying topical 2% lignocaine which is in congruence with our study of 4–5 min and bupivacaine as injection showed an onset of 6–10 min which also is in congruence with our study of 8–11 min.

The topical anesthetic effect peaked at 8–11 min with lignocaine and 15–18 min with bupivacaine in this study. 15–18 min of anesthesia with topical lignocaine and 25–30 min with topical bupivacaine afforded sufficient time for the operator to carry out multiple extractions if needed, let along single tooth extraction.

Therefore the onset of action and peak effect of bupivacaine is nearly double that of lignocaine which meant that the patient had to keep the mouth open for a shorter period of time with lignocaine. The operator too had the convenience of maintaining the dry field for a shorter period of time with lignocaine 5% gel.

The duration of action of bupivacaine ranged between 25 and 30 minutes. However, the average extraction procedure lasted just a couple of minutes, thereby no significant advantage of bupivacaine having a longer duration of action than lignocaine. 15–18 min of anesthesia with 5% lignocaine gel is more than sufficient to complete multiple extraction procedures.

The pain score was definitely higher with bupivacaine group than the lignocaine group. Statistically this was significant (P < 0.01) denoting more efficient analgesia with lignocaine 5% gel.

This topical analgesia achieved was adequate for extractions of grade II and grade III mobile teeth and were done painlessly. As the grade I mobile teeth extraction were painful, the gel application procedure was aborted and injectable technique was resorted (N = 17). This could be explained probably due to the lack of penetration of drug through the alveolar bone into the periapical area as the patient demonstrated no pain on probing deeply even beyond the mucoperiosteum but developed pain during the extraction procedure. This constituted only a small percentage i.e., 3.41% of the entire 510 extractions done in this study.

Therefore, it was concluded that the use of 5% lignocaine gel and 5% bupivacaine gel cannot be used for extraction of grade I mobile or normal teeth. It can be used successfully for grade II and grade III whether maxillary or mandibular both for anterior and posteriors.

No systemic toxicity was noticed during the entire study probably due to lower rate of absorption. No excessive bleeding was encountered in the entire study in congruence with the other study [15].

All in all, bupivacaine and lignocaine proved to be safe mode of anesthesia for grade II and grade III mobile teeth. The onset of anesthesia and the peaking effect of bupivacaine prove to be a little undesirable and inconvenient as compared to shorter time period of lignocaine.

Onset of action, peaking effect and pain being significantly less in 5% topical lignocaine gel group, it proved to be a better topical anesthesia than 5% bupivacaine gel.

The ease of technique, lack of usage of syringes and needles, absence of adverse reactions (systemic or local) and efficient analgesia for extraction of grade II and grade III mobile teeth could therefore point to a wider usage of topical 5% lignocaine hydrochloride gel.

Summary and Conclusion

It was observed that:

Lignocaine has quicker onset of action compared to that of bupivacaine (lignocaine 4–5 min, bupivacaine 8–11 min).

Peak effect was achieved faster with lignocaine than with bupivacaine i.e. 8–11 min and 15–18 min respectively.

Bupivacaine has longer duration of analgesia than lignocaine (lignocaine 15–18 min, bupivacaine 28–30 min).

Patients experienced more pain with bupivacaine than with lignocaine.

Extraction was painful with both gels while extracting grade I mobile maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth, therefore extractions could not be done.

Grade I anterior teeth (maxillary or mandibular) extractions were more painful with bupivacaine than with lignocaine.

No excessive salivation or bleeding was seen. Local irritation and systemic toxicity were not found with both the gels at concentration of 5%.

Extractions done with topical 5% lignocaine gel were less painful, onset and peaking action were faster than 5% bupivacaine gel, affording increased convenience to the operator and less distress to the patient.

It can therefore safely be concluded that 5% lignocaine gel is better than 5% bupivacaine gel as a topical anesthetic for extraction of grade II and grade III mobile teeth.

References

- 1.‘Pain’. The Dental clinics of North America (1978)

- 2.McKenzie R, Phitayakorn P, Uy NT, Chalasani J, Melnick BM, Kennedy RL, Vicinie AF., III Topical bupivacaine and etidocaine analgesia following fallopian tube banding. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36(5):510–514. doi: 10.1007/BF03005376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones JM, Nandapalan V. Manipulation of fractured nose: a comparison of local infiltration anesthesia and topical local anesthesia. Swed Dent J. 1985;22(1):185–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birch BR, Ratan P, Morley R, Cumming J, Smart CJ, Jenkins JD. Flexible cystoscopy in men; is topical anesthesia with lignocaine gel worthwhile? Br J Urol. 1994;73(2):155–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1994.tb07484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anusavice KJ (1996) Phillip’s science of dental materials, 10th edn, vol 4. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, PA, p 6

- 6.Pere P, Iizuka T, Rosenberg PH, Lindqvist C. Topical anesthesia of 5% eutectic mixture of lignocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) before removal of arch bar. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;30(3):153–156. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(92)90146-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meecahn JG. Intraoral topical anesthesia: a review. J Dent. 2000;28(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0300-5712(99)00041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elhakim M. Painless dental extraction in dental children. Anaesthesiol Reanim. 1993;18(3):80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greengrass SR, Andrzejowski J, Ruiz K. Topical bupivacaine for pain control following simple dental extractions. Br Dent J. 1998;184(7):354–355. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taware CP, Mazumdar S, Pendharkar M, Adani MH, Devarajan PV. A bioadhesive drug delivery system as an alternative to infiltration anesthesia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84(6):609–615. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill CJ, Orr DL., II A double blind crossover comparison of topical anesthetic. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;98(2):213–214. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1979.0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nortier YL, Haven JA, Koks CH, Beijnen JH. Preparation and stability testing of a hydro gel for topical analgesia. Pharm World Sci. 1995;17(6):214–217. doi: 10.1007/BF01870614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haasio J, Jokinen T, Numminen M, Rosenberg PH. Topical anaesthesia of gingival mucosa by 5% eutectic mixture of lignocaine and prilocaine or by 10% lignocaine spray. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;28(2):99–101. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(90)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawkins GP, Harrison NW, Ansell W. Urethral anesthesia with topical bupivacaine: a role for a longer acting agent. Br J Urol. 1995;76(4):484–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1995.tb07752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aps C, Reynolds F. The effect of concentration on vasoactivity of bupivacaine and lignocaine. Br J Anaesth. 1976;48(12):1171–1174. doi: 10.1093/bja/48.12.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]