Abstract

The ideal reconstructive material for cranioplasty is autogenous bone, however if it is not available the use of alloplastic materials is recommended. We present a case of 26-year-male patient who sustained compound depressed fracture of the frontal bone and associated anterior cranial fossa fracture following a road traffic accident. He was managed at hospital where the fractured bone fragments were removed but recently presented with watery discharge from nose (CSF rhinorrhoea) and cosmetic deformity of forehead. We describe the utilization of autogenous local frontal bone split calvarial graft for the reconstruction of the defect.

Keywords: Frontal fracture, CSF rhinorrhea, Calvaria, Graft

Introduction

It is well accepted that the ideal reconstructive material for cranioplasty is autogenous bone, however if it is not available the use of alloplastic materials is recommended [1, 2]. The necessity and advisability of using free and vascularized bone grafts in the reconstruction of small to moderate size anterior cranial fossa defects is controversial [3]. We describe the utilization of autogenous local frontal bone split calvarial graft for the reconstruction of the large post-traumatic frontal defect.

Case Report

A 26-year-male patient with head injury following a road traffic accident that happened two months back. At that time he sustained compound depressed fracture of the frontal bone and associated anterior cranial fossa fracture (Fig. 1). He was managed at a peripheral hospital where the all loose bone fragments were removed (Fig. 2). Now he presented with watery discharge from nose (CSF rhinorrhoea) and cosmetic deformity of forehead (Fig. 3). There was no history of fever, headache, vomiting, seizures or focal weakness. His general and systemic examination was normal. He was conscious, alert and oriented to time, place and person. Cranial nerves were normal except loss of smell. Motor and sensory examination was normal. There were no meningeal signs. His repeat CT scan showed large defect in the frontal bone as well as in the region of cribriform plate (Fig. 4). The patient underwent bifrontal craniotomy through a bicornal skin flap. There was large defect in the frontal bone (Fig. 5 inset). The dural was opened and gliotic brain tissue was removed from the cribriform plate. As the pericranium was very thin, temporalis fascia was used to cover the cribriform plate. Frontal bone defect was covered with split calvarial graft and the graft was fixed with plate and screws (Fig. 6). The screws were covered with fascia so it will touch the brain parenchyma. CSF rhinorrhoea subsided in the immediate postoperative period. Follow-up X-rays showed good position of the calvarial graft (Fig. 7).

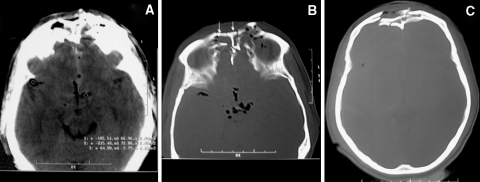

Fig. 1.

CT scan showing compound depressed fracture of the frontal bone

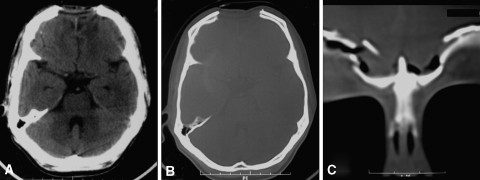

Fig. 2.

CT scan showing large bone defect after initial surgery

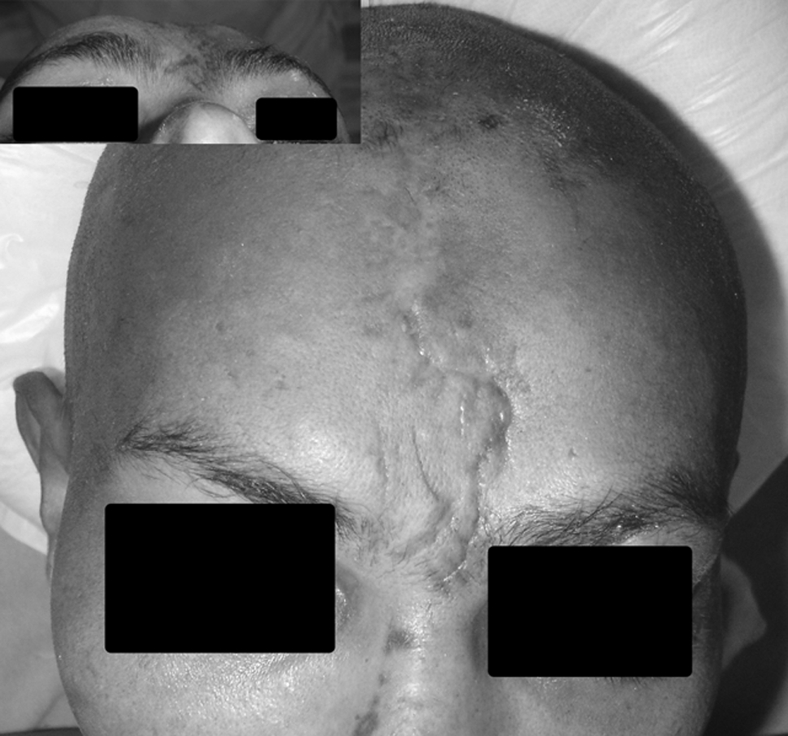

Fig. 3.

Clinical photograph showing the mid forehead depression

Fig. 4.

Intra-operative photograph showing the bone defect

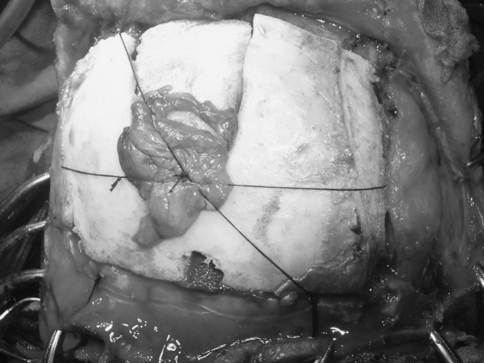

Fig. 5.

Photograph showing the reconstructed defect with split calvarial graft

Fig. 6.

Photograph showing the replaced frontal bone

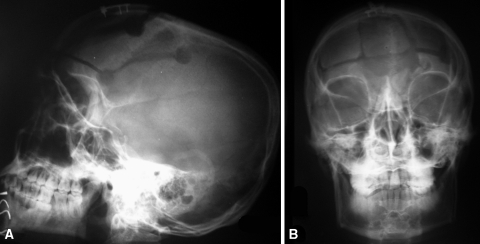

Fig. 7.

Follow-up x-ray showing the graft in place

Discussion

As described in the literature, the purposes of the reconstruction in present case were to cover the bone, to achieve the separation of the cranial cavity from the nasopharynx, the paranasal sinuses, and the orbit, to achieve the watertight dural reconstruction and to provide an adequate support of the brain tissue [3–6]. The available options to reconstruct the frontal bone include autogenous bone graft (particularly split-thickness calvarial bone grafts) [7], alloplastic materials (e.g. titanium mesh, hydroxyapatite cement, and prefabricated custom acrylic implants) [8] and the bioactive glass-coated fiber-reinforced composite (long-term studies are needed for use in humans) [9]. Methylmethacrylate is cheap, readily available and easy to use alloplastic material and remains the material of choice for cranioplasty [1, 10]. On the other hand with hydroxyapatite cement the long term results are disappointing [1, 11, 12]. The options to reconstruct the dural include free autografts (e.g. fascia lata and temporalis fascia) and vascularized flaps (i.e., free muscular flaps, pericranial or galeal flaps), assuming that an overlying vascular tissue will provide the long-term viability of the fascial graft [6, 13].

Conclusion

The utilization of autogenous local bone for reconstruction provides autogenous tissue, obviates second surgical intervention, donor site morbidity and is rarely rejected. In our circumstances where the finances may be a limiting factor the autogenous bone is the most appropriate [14–17].

References

- 1.Marchac D, Greensmith A. Long-term experience with methylmethacrylate cranioplasty in craniofacial surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(7):744–752. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mottaran R, Guarda-Nardini L, Fusetti S, Ferroneto G, Salar G. Reconstruction of a large post-traumatic cranial defect with a customized titanium plaque. J Neurosurg Sci. 2004;48(3):143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamamoto Y, Minakawa H, Yoshida T, Igawa H, Sugihara T, Ohura T, Nohira K. Role of bone graft in reconstruction of skull base defect: is a bone graft necessary. Skull Base Surg. 1993;3(4):223–229. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1060587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Disa JJ, Rodriguez VM, Cordeiro PG. Reconstruction of lateral skull base oncological defects: the role of the free tissue transfer. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41(6):633–639. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle JO, Shah KC, Shah JP. Craniofacial resection for malignant neoplasms of the skull base: an overview. J Surg Oncol. 1998;69(4):275–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199812)69:4<275::AID-JSO13>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gil Z, Abergel A, Leider-Trejo L, Khafif A, Margalit N, Amir A, Gur E, Fliss DM. A comprehensive algorithm for anterior skull base reconstruction after oncological resections. Skull Base. 2007;17(1):25–37. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendus J, Draf W, Bockmühl U (2005) Reconstruction of the frontoorbital frame using split-thickness calvarial bone grafts. Laryngorhinootologie 84(12):899–904 (Article in German) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Tadros M, Costantino PD. Advances in cranioplasty: a simplified algorithm to guide cranial reconstruction of acquired defects. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24(1):135–145. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1037455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuusa SM, Peltola MJ, Tirri T, Lassila LV, Vallittu PK. Frontal bone defect repair with experimental glass-fiber-reinforced composite with bioactive glass granule coating. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;82(1):149–155. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greene AK, Warren SM, McCarthy JG. Onlay frontal cranioplasty using wire reinforced methyl methacrylate. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2008;36(3):138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen TM, Wang HJ, Chen SL, Lin FH. Reconstruction of post-traumatic frontal-bone depression using hydroxyapatite cement. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(3):303–308. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000105522.32658.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddi SP, Stevens MR, Kline SN, Villanueva P. Hydroxyapatite cement in craniofacial trauma surgery: indications and early experience. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 1999;5(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasegawa M, Torii S, Fukuta K, Saito K. Reconstruction of the anterior cranial base with the galeal frontalis myofascial flap and the vascularized outer table calvarial bone graft. Neurosurgery. 1995;36(4):725–731. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199504000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal A, Badhu B, Wakode P (2007) Management of a case of massive orbital fracture associated with intracranial injury. Niger J Ophthalmol 15(1):13–16 (Online). Available: http://www.ajol.info/viewarticle.php?id=37975

- 15.Agrawal A, Borle RM, Bhola N, Daga A, Bora S, Sachdeva S. Multiple fractures involving the orbit and incidental finding of large fourth ventricular epidermoid. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20(1):261–262. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318184339b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrawal A, Joharapurkar SR, Borle RM, Richa A. Giant ostoid osteoma of the frontal bone: case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg (India) (accepted for publication)

- 17.Rajendra PB, Mathew TP, Agrawal A, Sabharawal G. Characteristics of associated craniofacial trauma in patients with head injuries: An experience with 100 cases. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2009;2(2):89–94. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.50742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]