Abstract

The present study examined the association between positive traits, pain catastrophizing, and pain perceptions. We hypothesized that pain catastrophizing would mediate the relationship between positive traits and pain. First, participants (n = 114) completed the Trait Hope Scale, the Life Orientation Test- Revised, and the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Participants then completed the experimental pain stimulus, a cold pressor task, by submerging their hand in a circulating water bath (0º Celsius) for as long as tolerable. Immediately following the task, participants completed the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ-SF). Pearson correlation found associations between hope and pain catastrophizing (r = −.41, p < .01) and MPQ-SF scores (r = −.20, p < .05). Optimism was significantly associated with pain catastrophizing (r = −.44, p < .01) and MPQ-SF scores (r = −.19, p < .05). Bootstrapping, a non-parametric resampling procedure, tested for mediation and supported our hypothesis that pain catastrophizing mediated the relationship between positive traits and MPQ-SF pain report. To our knowledge, this investigation is the first to establish that the protective link between positive traits and experimental pain operates through lower pain catastrophizing.

1. Introduction

Pain affects more than 76 million people in the United States, or about 26% of the population. Annual estimates of healthcare costs for those suffering with chronic pain exceed $6,000 per person (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). Moreover, chronic pain is a continual burden affecting both physical and mental functioning. Negative consequences of chronic pain can include long hours of rehabilitation, loss of work and income, and hospitalization (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006).

Pain is a complex phenomenon influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors. The control gate theory of pain is a popular psychological explanation that suggests that perception and interpretation are important in understanding pain(Siegele, 1974).When individuals assess pain, their characteristic ways of thinking (i.e., cognitive sets), and their feelings are significant determinants of their subsequent pain response. For instance, anxiety can intensify the experience of pain, whereas, positive affect can attenuate pain (Siegele, 1974). The present study focused on the psychological experience of pain and addressed the influence of positive psychological traits and negative cognitive sets; specifically, how hope, optimism and pain catastrophizing affected pain outcomes.

Pain catastrophizing is an exaggerated negative response to actual or anticipated pain. It is the tendency to ruminate, magnify, or feel helplessness about pain experience (Sullivan, Bishop, & Pivik, 1995). Previous studies have found that pain catastrophizers report more pain in clinical and experimental settings (France, France, al'Absi, Ring, & McIntyre, 2002; Rhudy et al., 2009). Further, pain catastrophizers generally report significantly more pain-related thoughts, and experience more emotional distress, and greater pain intensity than non-catastrophizers (Moldovan, Onac, Vantu, Szentagotai, & Onac, 2009).

Negative personality traits, or response patterns and their association with pain have historically been the primary focus of clinical research (Pearce & Porter, 1983). Neuroticism, a negative psychological trait that can produce nervousness, moodiness, and sensitivity to negative stimuli, has been shown to influence pain report (Charles, Gatz, Kato, & Pedersen, 2008), and higher neuroticism can provoke more negative affect in emotion-inducing situations (Larsen & Ketelaar, 1989). Other recent research suggests that pain catastrophizing mediates the relationship between self-handicapping and pain. Self-handicapping is a defense mechanism whereby individuals generate hurdles prior to a performance that affects their attributions after the performance. Individuals who self-handicap tend to pain catastrophize and report higher pain (Uysal & Lu, 2010).

Within the past decade, there has been a shift from studying negative traits and emotions to also examining the important role of positive traits and emotions (Fredrickson, 2001; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Emerging evidence suggests that levels of hope, a positive psychological construct, and optimism, described as a generalized expectancy of positive outcomes are linked with lower pain reports (Berg, Snyder, & Hamilton, 2008; Geers, Wellman, Heifer, Fowler, & France, 2008; Snyder et al., 2005). In addition, positive emotions and psychological resilience are associated with less pain catastrophizing (Ong, Zautra, & Reid, 2010).

Optimism and hope are positive traits that both have links to adaptive outcomes(Scheier & Carver, 1985; 1987). Despite their similarities, the two constructs differ in important ways. Optimism is a dispositional trait conceived as an explanatory style whereby individuals focus their cognitions on distancing themselves from negative outcomes (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Conversely, hope is a construct conceived as dispositional (Snyder et al., 1991), state (Snyder et al., 1996), or goal-specific (Feldman, Rand, & Kahle-Wrobleski, 2009). Importantly, compared to optimism, hope has been shown to better describe an individual’s emphasis on positive, goal-directed cognitions (Snyder, 2002).

Previous research suggests that hope and optimism are strongly associated but not identical, with correlations ranging from .51 and .55 (Magaletta & Oliver, 1999; Rand, 2009). In addition, statistical modeling has differentiated hope and optimism as distinct but related constructs. Bryant and Cvengros (2004) found that when analyzing hope and optimism, a goodness-of-fit model with separate second-order factors had greater explanatory power than a model analyzing the constructs as a single global factor. Moreover, hope and optimism had divergent patterns of association with coping and self-efficacy. They suggest that researchers interested in future physical and emotional outcomes should examine the constructs separately.

There is a need to examine the relationships among positive psychological traits, pain, and negative reactions to pain (i.e., pain catastrophizing). Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to describe the mechanism through which positive traits and pain perception are linked. We tested the hypothesis that pain catastrophizing mediates the relationship between the positive traits, hope and optimism, and pain perception.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

An initial telephone screening of 274 participants deemed 96 participants medically ineligible. As we obtained data for this study as part of larger study (Pulvers & Hood, 2010) for which smoking status was an important variable, 32 participants were ineligible due to an unstable smoking rate (any smoking rate was acceptable, so long as participants were smoking at their current rate for at least one year). Results from the larger study indicated that gender and smoking status were associated with pain perception (Pulvers & Hood, 2010), which is consistent with previous literature (Girdler et al., 2005; Kanarek & Carrington, 2004; Sullivan, Trip, & Cantor, 2000; Riley, Robinson, Wise, Myers, & Fillingim, 1998; Jamner, Girdler, Shapiro, & Jarvik, 1998). Therefore, we controlled for gender and smoking status in the present study. A further 32 participants were eligible but did not appear for their scheduled appointment.

Eligible participants who completed the entire study (n = 114, 57 males)were aged 18 – 73 years old (M = 34, SD = 14), and 107 completed all experimental measures. Participants predominantly identified themselves as Caucasian (65%), most had completed some college (50%), and the majority (72%) had an annual household income of less than $34,000. Smokers were approximately 50% of the sample, and smoked an average of 10 cigarettes a day. California State University San Marcos Institutional Review Board approved the protocol and all participants provided informed written consent prior to participation. Participants affiliated with the university (n = 9) received compensation of $10, all other participants (n = 105) received $25 for one hour of their time.

2.2. Procedure

Researchers recruited participants through newspaper and Internet advertisements. Participants first completed a phone survey that assessed demographics and eligibility. Participants did not abstain from eating or drinking, and smokers could smoke ad-lib prior to the experiment. Criteria for medical exclusion included the presence of any contraindicative medical conditions self-reported by the participant (e.g., injury to non-dominant hand, circulatory problems, or a history of fainting or seizures). Participants completed a pre-experimental survey, which included the Trait Hope Scale, the Life Orientation Test-Revised and the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Participants then completed the cold pressor task. Research assistants instructed participants to hold their non-dominant hand in the water as long as tolerable. When participants could no longer tolerate the pain, they could remove their hand from the bin of cold water. There was an uninformed maximum time limit of five minutes (Girdler, et al., 2005). Directly following the cold-water task, participants completed the McGill Pain Questionnaire-Short Form. Finally, participants confirmed that they were not experiencing pain or discomfort and received a referral should they experience pain or discomfort.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Trait Hope Scale

The Trait Hope Scale (THS) developed by Snyder et al. (1991) is an eight-item measure (with four additional distractor items) developed to quantify dispositional hope. Two subscales, agency (e.g., I energetically pursue my goals) and pathways (e.g., there are many ways around any problem), each comprise four items measured on an 8-point Likert scale. The total THS score (range 8 to 64) is the sum of the four pathways and four agency items, with higher scores representing higher hope levels. The THS has good test-retest reliability over three, eight, and ten weeks (.85, .73, and .79, respectively), and coefficient alphas range from .73 to .86 (Curry, Snyder, Cook, Ruby, & Rehm, 1997; Snyder, et al., 1991). The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .89.

2.3.2. The Life Orientation Test – Revised

The Life Orientation Test – Revised (LOT-R; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994) is a six-item measure (with four additional filler items) developed to measure dispositional optimism. Three items are positively phrased (e.g., "I’m always optimistic about my future"), and three items are negatively phrased (e.g., "I hardly ever expect things to go my way"). Participants rated each item by indicating the extent of their agreement along a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree”. Previous research demonstrated test-retest reliability of .68, .60, .56, and .79, at four, twelve, twenty-four and twenty-eight months respectively (Scheier, et al., 1994). The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .82.

2.3.3. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS; Sullivan, et al., 1995) is a 13-item measure intended to quantify catastrophizing cognitions in relation to painful experiences. The PCS has three subscales; 4 items assess rumination, (e.g., I can’t seem to keep it out of my mind), 3 items assess magnification, (e.g., I think of other painful experiences), and 6 items assess helplessness, (e.g., I feel I can’t go on). Participants rate the items on a five-point Likert scale with scoring ranging from zero (not at all) to four (always). The total score ranges from 0 to 52. High total scores indicate more catastrophic cognitions. Previous research demonstrated test-retest reliability from .73 to .75 (Lamé, Peters, Kessels, van Kleef, & Patijn, 2008; Sullivan, et al., 1995). The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .94

2.3.4. Cold Pressor Apparatus

The pain stimulus, a refrigerating bath (Jeio Tech Inc) continually circulated water cooled to 0º Celsius. Prior research has established the cold pressor task as harmless, with the exception of those individuals who meet certain exclusion criteria (von Baeyer, Piira, Chambers, Trapanotto, & Zeltzer, 2005).

2.3.5. The McGill Pain Questionnaire- Short-Form

The McGill Pain Questionnaire-Short Form (MPQ-SF) is a pain rating scale that consists of 15-descriptor items, 11 items relate to sensory pain dimensions (e.g. shooting), and four items relate to affective pain dimensions (e.g. fearful) (Melzack, 1987). Participants rated items on a 4-point scale, ranging from zero (no pain) to four (severe). Total scores can range from 0 to 60, with higher scores representing higher pain levels. The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .87.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Pearson correlation evaluated the relationships between hope and optimism, pain catastrophizing, and pain report. Bootstrapping, a non-parametric resampling procedure to assess indirect effects, tested for mediation. Bootstrapping is an approach that does not make assumptions about the shape of the distribution of the variables or the sampling distribution of the statistic (Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008). Often, only large samples have exact normal distributions; however, as large-sample theory does not provide the basis for bootstrapping, researchers can apply the procedure to small samples with more confidence. In addition, bootstrapping avoids the power problems associated with variables that are non-normally distributed (Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

From our original dataset of 114 cases, random sampling with replacement generated a bootstrap sample of 114 cases. Repeating the process 5,000 times provided the basis for the bootstrap estimates. Means and standard errors of the 5,000 samples were then calculated. We used Bias Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) 95% confidence intervals (CI) to test for significance, as they adjust for possible bias and skewness in the bootstrap distribution. If zero was not within the 95% confidence interval, we concluded that the indirect effect was significantly different from zero at p< .05, two tailed (Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

3. Results

3.1. Correlations

We hypothesized that lower hope and optimism would be associated with higher pain catastrophizing and higher pain. The correlation between hope and optimism (r = .61, p < .01) was similar to previous research studies that found the constructs to be related yet distinct. Hope and pain catastrophizing were significantly associated (r = −.41, p <.01) and hope and total scores on the MPQ- SF were significantly associated (r = −.20, p<.05). In addition, optimism and pain catastrophizing were significantly associated (r = −.44, p < .01) and optimism and total scores on the MPQ-SF scores were significantly associated (r = −.19, p < .05). These results indicated that lower levels of hope and/or optimism are in fact associated with higher levels of pain catastrophizing and higher total scores on the MPQ-SF.

3.2. Mediation

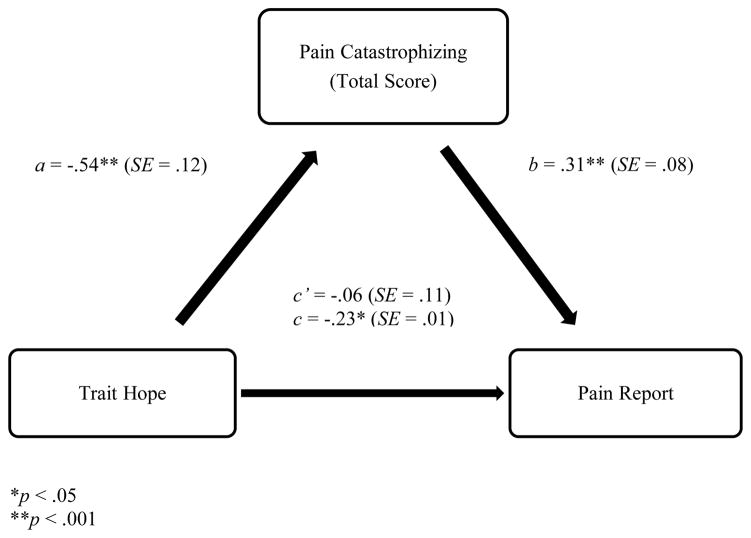

To determine if pain catastrophizing was a mediator of the positive traits and pain perception, we conducted bootstrap analyses to estimate the direct and indirect effects. Mediation analyses indicate if the total effect (weight c) of the independent variable (IV; hope or optimism) on a dependent variable (DV; pain) is comprised of a direct effect (weight c’) of the IV on the DV and an indirect effect (weight a x b) of the IV on the DV through a predicted mediator (pain catastrophizing). Weight a denotes the IV on the mediator, whereas, weight b is the effect of the mediator on the DV.

3.3. Bootstrapping Procedure

The total effect (weight c) of trait hope on pain was − .23, p < .05 and the direct effect (weight c’) of trait hope on pain was − .06, p > .05. The total direct effect (the difference between the total and direct effects) has a point estimate of − .16 and a 95% BCa CI of− .31 to − .07. The confidence intervals suggested that, even after controlling for smoking status and gender, the indirect effect of trait hope is significantly different from zero at p< .05. The directions of paths a and b (see Figure 1) are consistent with the interpretation that lower hope leads to higher pain catastrophizing, which in turn leads to higher pain perception. Thus, pain catastrophizing was a significant mediator of hope and pain.

Fig. 1.

Pain Catastrophizing as a mediator of Trait Hope and Total Score on the MPQ-SF (Pain Perception).

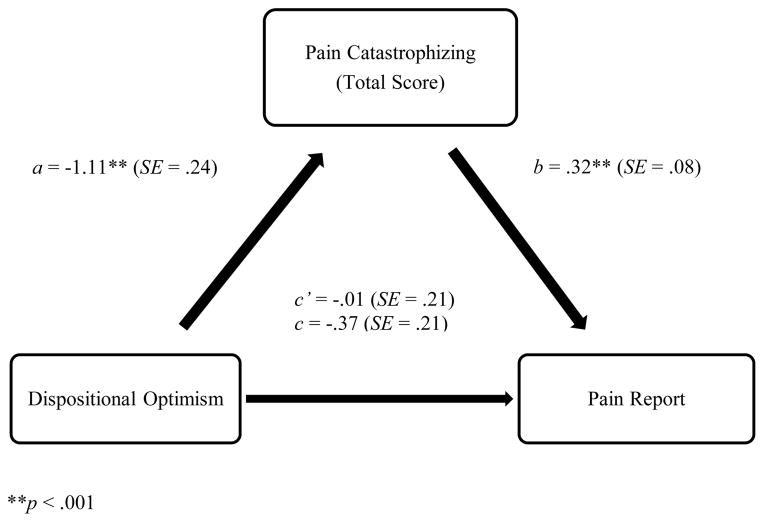

The total effect (weight c) of optimism on pain perception was − .37, p < .05 and the direct effect (weight c’) of optimism on pain was − .01, p > .05. The total direct effect (the difference between the total and direct effects) has a point estimate of − .36 and a 95% BCa CI of − .63 to − .17. The confidence intervals suggested that, even after controlling for smoking status and gender, the indirect effect of optimism is significantly different from zero at p< .05. The directions of paths a and b (see Figure 2) are consistent with the interpretation that lower optimism leads to higher pain catastrophizing, which in turn leads to higher pain perception. Thus, pain catastrophizing was a significant mediator of optimism and pain perception.

Fig. 2.

Pain Catastrophizing as a mediator of Dispositional Optimism and Total Score on the MPQ-SF (Pain Perception)

An examination of the rumination, magnification and helplessness subscales of the PCS (the specific indirect effects) indicated that all three subscales are mediators of hope and pain perception, and of optimism and pain perception since none of their 95% BCa CI contains zero (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Indirect Effects of the Pain Catastrophizing Subscales on Positive Traits

| Mediator | Point Estimate | SE | BCa 95% CI lower | BCa 95% CI upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait Hope as IV | ||||

| Rumination | − .10 | .05 | − .22 | − .03 |

| Helplessness | − .13 | .05 | −.27 | − .05 |

| Magnification | − .15 | .06 | − .30 | − .06 |

|

| ||||

| Optimism as IV | ||||

| Rumination | − .19 | .08 | − .40 | − .06 |

| Helplessness | − .29 | .11 | − .55 | − .12 |

| Magnification | − .37 | .13 | − .67 | − .16 |

Note. Based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. BCa = bias corrected and accelerated; CI = confidence interval.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated whether pain catastrophizing mediated the relationship between hope and optimism and pain perception. Our findings indicated that individuals low in hope or optimism reported higher pain catastrophizing and had higher pain reports. These results are consistent with the literature that pain catastrophizing often mediates pain reports (Ong, et al., 2010; Uysal & Lu, 2010), and that lower levels of hope and/or optimism result in higher levels of pain perception(Berg, et al., 2008; Geers, et al., 2008). However, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to establish that the protective link between positive traits and experimental pain perception operates through lower pain catastrophizing.

All three subscales (rumination, magnification and helplessness) of the PCS individually mediated the relationship between hope, optimism and pain report. Previous research had only found that the helplessness, but not rumination or magnification, mediated the relationship between self-handicapping and pain (Uysal & Lu, 2010). The association between positive traits, pain catastrophizing, and pain report appears especially robust.

Our findings suggest that the psychological resilience attributed to those with positive psychological traits, such as hope and optimism, works through lower pain catastrophizing in order to modify pain perception. Hope is a trait composed of agency and pathways towards a desired outcome or goal (Snyder et al., 1991). In a situation in which an individual experiences pain, those who have higher hope can generate different ways of dealing with pain by creating routes (pathways) and exerting control (agency), are less likely to catastrophize about pain, and consequently likely to experience less pain. However, the present study did not explicitly measure this possible mechanism. Objective measures such as brain imaging, might be better able to distinguish some of the differences in brain processing between pathways and agency in individuals experiencing pain. This would be especially interesting as new research found that higher levels of neuroticism significantly influences brain processing during visceral pain (Coen et al., 2011).

Optimism may foster confidence to overcome and succeed in a given scenario (Scheier & Carver, 1987). This confidence might help people remain positive in painful conditions leading them to catastrophize less about their pain and therefore report less pain (Berg, et al., 2008; Geers, et al., 2008). We found that those who catastrophize have lower levels of these positive traits, which, in turn, is associated with higher pain. Individuals who are unable to create pathways and assert agency or optimism are likely to ruminate, magnify, or feel helplessness about their pain experience.

Although the present investigation was community-based, the recruitment strategy yielded a majority sample of low-income, Caucasian adults. Researchers should use caution generalizing the study results to other populations, and we advise replication studies with more diverse samples. In terms of our experimental paradigm, participants filled out the pain questionnaire after the cold pressor task, so their pain report may not reflect their actual level of pain during the procedure. In order to eliminate the issue of pain report accuracy, future studies could have participants rate their pain after an allotted time during the cold pressor task (Sullivan et al., 2000). Further, the present study utilized an experimental pain stimulus; our participants did not suffer from chronic pain, and could remove their hand from the cold pressor. Future research should explore whether the link between hope or optimism and pain through pain catastrophizing persists in chronic pain sufferers. Finally, the present study measured only two positive traits; future investigation of additional positive traits would be valuable.

Despite these limitations, the present study does provide novel information that might prove especially helpful in a clinical setting. For example, a doctor interviewing a patient before a painful procedure could assess whether the patient has high levels of positive psychological traits, such as hope and optimism. High hope patients may have fewer problems with pain catastrophizing and subsequent pain management. Eliott and Olver (2002) found that cancer patients often use the word "hope" in their speech without provocation, and Larsen, Edey and Lemay (2007) suggested that requests like, “Tell me about a time when something turned out better than you expected” could indicate a patient's hope level. Patients with lower levels of positive psychological traits may need further counseling and assistance in order to deal with their pain catastrophizing and subsequent elevated feelings of pain. Given the need to reduce pain, future studies that implement our findings in a clinical setting could help to improve the quality of life for those suffering from pain.

We examine positive traits, pain catastrophizing, and pain report.

Participants completed an experimental pain stimulus, a cold pressor task.

Associations found between positive traits, pain catastrophizing and pain report.

Pain catastrophizing mediated the relationship between positive traits and pain.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by NIGMS MARC Grant GM-08807. The authors would like to thank Sara Bayles, Jessica Edwards, Sara Margetta, Anna Meldau, Ines Pandzic, Ashleigh Shepard, Mae Talicuran and Laura Thode for their help with data collection and management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berg CJ, Snyder CR, Hamilton N. The effectiveness of a hope intervention in coping with cold pressor pain. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(6):804–809. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, Cvengros JA. Distinguishing hope and optimism: Two sides of a coin, or two separate coins? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23(2):273–302. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.2.273.31018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S, Gatz M, Kato K, Pedersen NL. Physical health 25 years later: The predictive ability of neuroticism. Health Psychology. 2008;27(3):369–378. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen SJ, Kano M, Farmer AD, Kumari V, Giampietro V, Brammer M, Aziz Q. Neuroticism Influences Brain Activity During the Experience of Visceral Pain. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(3):909–917.e901. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry LA, Snyder CR, Cook DL, Ruby BC, Rehm M. Role of hope in academic and sport achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(6):1257–1267. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliott J, Olver I. The discursive properties of 'hope': A qualitative analysis of cancer patients' speech. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12(2):173–193. doi: 10.1177/104973202129119829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DB, Rand KL, Kahle-Wrobleski K. Hope and goal attainment: Testing a basic prediction of hope theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2009;28(4):479–497. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.4.479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- France CR, France JL, al’Absi M, Ring C, McIntyre D. Catastrophizing is related to pain ratings, but not nociceptive flexion reflex threshold. Pain. 2002;99(3):459–463. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00235-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist. 2001;56(3):218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers AL, Wellman JA, Heifer SG, Fowler SL, France CR. Dispositional optimism and thoughts of well-being determine sensitivity to an experimental pain task. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36(3):304–313. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdler SS, Maixner W, Naftel HA, Stewart PW, Moretz RL, Light KC. Cigarette smoking, stress-induced analgesia and pain perception in men and women. Pain. 2005;114(3):372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamner LD, Girdler SS, Shapiro D, Jarvik ME. Pain inhibition, nicotine, and gender. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6(1):96–106. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.6.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanarek RB, Carrington C. Sucrose consumption enhances the analgesic effects of cigarette smoking in male and female smokers Sucrose, nicotine and pain sensitivity. [Article] Psychopharmacology. 2004;173(1/2):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamé IE, Peters ML, Kessels AG, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Test-retest stability of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale and the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia in chronic pain patients over a longer period of time. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(6):820–826. doi: 10.1177/1359105308093866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen D, Edey W, Lemay L. Understanding the role of hope in counselling: Exploring the intentional uses of hope. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2007;20(4):401–416. doi: 10.1080/09515070701690036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Ketelaar T. Extraversion, neuroticism and susceptibility to positive and negative mood induction procedures. Personality and Individual Differences. 1989;10(12):1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(89)90233-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(6):803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaletta PR, Oliver JM. The hope construct, will, and ways: Their relations with self-efficacy, optimism, and general well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55(5):539–551. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199905)55:5<539::aid-jclp2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan AR, Onac IA, Vantu M, Szentagotai A, Onac I. Emotional distress, pain catastrophizing and expectancies in patients with low back pain. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies. 2009;9(1):83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Zautra AJ, Reid MC. Psychological resilience predicts decreases in pain catastrophizing through positive emotions. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(3):516–523. doi: 10.1037/a0019384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce S, Porter S. Personality variables and pain expectations. Personality and Individual Differences. 1983;4(5):559–561. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(83)90090-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvers K, Hood A. Cigarette Smoking and Gender Effects on Pain Sensitivity in a Cold Pressor Task. Poster presented at the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students; Charlotte, North Carolina. 2010. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Rand KL. Hope and optimism: Latent structures and influences on grade expectancy and academic performance. Journal of Personality. 2009;77(1):231–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhudy JL, France CR, Bartley EJ, Williams AE, McCabe KM, Russell JL. Does pain catastrophizing moderate the relationship between spinal nociceptive processes and pain sensitivity? The Journal of Pain. 2009;10(8):860–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, III, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Myers CD, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: A meta-analysis. Pain. 1998;74(2–3):181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4(3):219–247. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Dispositional Optimism an Physical Well-Being: The Influence of Generalized Outcome Expectancies on Health. [Article] Journal of Personality. 1987;55(2):169–210. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.ep8970713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. [Empirical Study] Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(6):1063–1078. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegele DS. The gate control theory. American Journal of Nursing. 1974;74(3):498–502. doi: 10.2307/3469644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR. Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13(4):249–275. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1304_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Berg C, Woodward JT, Gum A, Rand KL, Wrobleski KK, Hackman A. Hope Against the Cold: Individual Differences in Trait Hope and Acute Pain Tolerance on the Cold Pressor Task. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(2):287–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Harney P. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60(4):570–585. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Sympson SC, Ybasco FC, Borders TF, Babyak MA, Higgins RL. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;2:321–335. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(4):524–532. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJL, Tripp DA, Santor D. Gender differences in pain and pain behavior: The role of catastrophizing. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24(1):121–134. doi: 10.1023/a:1005459110063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uysal A, Lu Q. Self-handicapping and pain catastrophizing. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49(5):502–505. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von Baeyer CL, Piira T, Chambers CT, Trapanotto M, Zeltzer LK. Guidelines for the Cold Pressor Task as an Experimental Pain Stimulus for Use With Children. The Journal of Pain. 2005;6(4):218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Web References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New report finds that pain affects millions of Americans. 2006 Retrieved March 7, 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/06facts/hus06.htm.