Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) has been shown to regulate adaptive thermogenesis and glucose metabolism. Here we show that PGC-1α regulates triglyceride metabolism through both farnesoid X receptor (FXR)-dependent and -independent pathways. PGC-1α increases FXR activity through two pathways: (1) it increases FXR mRNA levels by coactivation of PPARγ and HNF4α to enhance FXR gene transcription; and (2) it interacts with the DNA-binding domain of FXR to enhance the transcription of FXR target genes. Ectopic expression of PGC-1α in murine primary hepatocytes reduces triglyceride secretion by a process that is dependent on the presence of FXR. Consistent with these in vitro studies, we demonstrate that fasting induces hepatic expression of PGC-1α and FXR and results in decreased plasma triglyceride levels in wild-type but not in FXR-null mice. Our data suggest that PGC-1α plays an important physiological role in maintaining energy homeostasis during fasting by decreasing triglyceride production/secretion while it increases fatty acid β-oxidation to meet energy needs.

Keywords: FXR, PGC-1α, HNF4α, PPARγ, triglyceride

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) was originally identified as a coactivator of PPARγ and, as such, it was shown to play a critical role in the control of adaptive thermogenesis (Puigserver et al. 1998). Subsequent studies demonstrated that PGC-1α is involved in the expression of multiple genes that regulate mitochondrial biogenesis (Wu et al. 1999), glucose uptake in muscle (Michael et al. 2001), hepatic gluconeogenesis in liver (Yoon et al. 2001), and skeletal muscle fiber-type switching (Lin et al. 2002b; Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003).

Fasting markedly induces the hepatic expression of PGC-1α, which subsequently stimulates the entire program of genes involved in hepatic gluconeogenesis (Yoon et al. 2001). The observation that the same gluconeogenic genes could be induced merely by infecting primary hepatocytes with adenovirus containing the gene encoding PGC-1α provided critical evidence for the importance of PGC-1α in gluconeogenesis (Yoon et al. 2001). Induction of these gluconeogenic genes is thought to depend on the interaction of PGC-1α with hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α), a transcription factor that is necessary for transcriptional activation of these genes (Rhee et al. 2003). PGC-1α has also been shown to physically interact with several nuclear hormone receptors (Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003), including the glucocorticoid receptor (Knutti et al. 2000), PPARα (Vega et al. 2000), and PPARγ (Puigserver et al. 1998).

The farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, forms an obligate heterodimer with RXR (Forman et al. 1995; Seol et al. 1995), and is activated by bile acids (Makishima et al. 1999; Parks et al. 1999; Wang et al. 1999). FXR contains a number of domains that are conserved in most members of this superfamily. These include a poorly defined N-terminal transactivation domain, a highly conserved DNA-binding domain, a hinge region, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain that is involved in dimerization, ligand binding, and transactivation (Glass 1994; Mangelsdorf and Evans 1995). FXR is most highly expressed in liver, intestine, kidney, and adrenal gland with reduced levels reported in fat and heart (Forman et al. 1995; Lu et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2003).

The identification of FXR target genes and the characterization of FXR-null mice provided important insights into the physiological importance of this nuclear receptor. FXR target genes, which include the ileal bile acid-binding protein (I-BABP; Grober et al. 1999; Makishima et al. 1999), small heterodimer protein (SHP; Goodwin et al. 2000; Lu et al. 2000), apoC-II (Kast et al. 2001), bile salt export pump (BSEP; Ananthanarayanan et al. 2001), phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP; Laffitte et al. 2000; Urizar et al. 2000), MRP2 (ABCC2; Kast et al. 2002), and syndecan-1 (Anisfeld et al. 2003), are involved in the regulation of bile acid, cholesterol, and lipoprotein metabolism (Edwards et al. 2002). The identification of these target genes coupled with the observation that FXR-null mice exhibited a proatherogenic lipoprotein profile and had elevated serum levels of bile acids, triglycerides, and cholesterol (Sinal et al. 2000), led to the hypothesis that FXR plays a key role in regulating blood lipids (Sinal et al. 2000; Edwards et al. 2002). In addition, the demonstration that FXR-null, but not wild-type mice exhibited hepatic toxicity when fed a diet enriched in either fat and cholesterol or bile acids suggested that FXR plays an important role in maintaining normal liver function (Sinal et al. 2000).

Recent studies have shown that four mRNAs are transcribed from the single FXR gene as the result of use of two distinct promoters that initiate transcription from either exon 1 or exon 3, and as a result of alternative splicing between exon 5 and exon 6 (Huber et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2003). The four transcripts and the four corresponding protein isoforms have been termed FXRα1, FXRα2, FXRβ1, and FXRβ2 (Huber et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2003). We have renamed these four isoforms FXRα1, FXRα2, FXRα3, and FXRα4, respectively, to conform to the nomenclature used for other nuclear receptors. This renaming is also necessitated by the recent identification of FXRβ, a distinct murine gene (a pseudogene in humans) that has 44% identity to FXRα (Otte et al. 2003).

The 5′ or 3′ promoters of the murine FXRα (referred to as FXR in the text below) gene regulate the expression of either FXRα1 plus FXRα2 or FXRα3 plus FXRα4 transcripts, respectively (Zhang et al. 2003). FXRα1 and FXRα3 contain four amino acids (MYTG), immediately 3′ of the DNA-binding domain, which are absent from FXRα2 and FXRα4 (Zhang et al. 2003). The presence of the MYTG motif decreases the binding of the FXR/RXR heterodimer to FXREs in vitro and affects the transcriptional activation of some, but not all, genes (Anisfeld et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2003). For example, FXRα2 and FXRα4 highly activate transcription of I-BABP and syndecan-1, whereas FXRα1 or FXRα3 is ineffective (Anisfeld et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2003). In contrast, all four FXR isoforms transcriptionally activate BSEP, SHP, and PLTP to similar extents (Anisfeld et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2003). Although the four FXR mRNAs are known to be differentially expressed in various tissues, the factors affecting the transcription of the FXR gene per se and the coactivators that are necessary for activation of FXR target genes remain unknown.

In the present study we initially used fasted mice to determine whether FXR expression and/or activity were affected by the nutritional status. These studies demonstrated that fasting selectively induced FXR transcripts initiated from the 3′ (internal) promoter of the murine gene. Additional studies demonstrated that selective activation of the 3′ FXR promoter could be recapitulated in cultured cells following ectopic expression of PGC-1α. We demonstrate that PGC-1α activates FXR, resulting in increased expression of FXR target genes. This latter activation is dependent on a novel interaction between the 180-400 amino acid domain of PGC-1α and the DNA-binding domain of FXR. The effect of fasting on FXR expression/activity has physiological consequences, as shown by the findings that fasting decreases plasma triglyceride levels in wild-type mice but not in FXR-null mice. Consistent with this observation, we report that ectopic expression of PGC-1α decreases triglyceride secretion in wild-type primary hepatocytes but not in FXR-null cells. Taken together, our data suggest that PGC-1α is a central regulator of hepatic FXR function, where it regulates triglyceride metabolism to ensure energy demands during fasting.

Results

Modulation of FXR by nutritional status

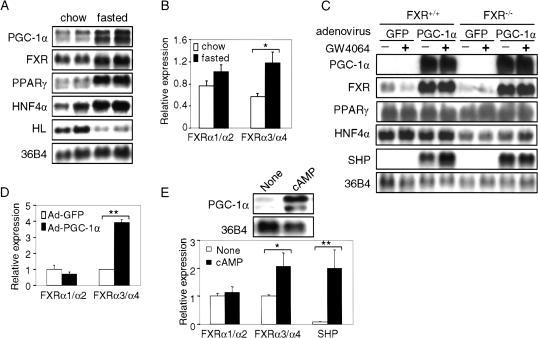

Previous studies have shown that activated FXR regulates the expression of genes that control the metabolism of bile acids, cholesterol, and lipoproteins (Sinal et al. 2000; Edwards et al. 2002). To investigate the effect of the nutritional status on the hepatic expression of FXR, mice were fasted for 24 h prior to isolation of RNA. Northern blot assays indicated that a number of hepatic mRNAs, including those encoding PGC-1α, FXR, PPARγ, and HNF4α, were induced in the livers of fasted mice (Fig. 1A; data not shown). The mRNA levels of SHP, a known FXR target gene, were also induced in the livers of fasted mice (0.84 ± 0.05 vs. 1.6 ± 0.4; n = 4, p < 0.05). The induction of specific hepatic mRNAs in response to fasting was selective, as shown by the observation that hepatic lipase mRNA levels were repressed under these conditions (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Fasting and PGC-1α induce FXR mRNA levels. (A) Northern blot analysis of gene expression in fasted livers. FXR+/+ and FXR-/- mice (n = 4 or 5 per group) were fed either standard chow diet or fasted for 24 h. Total hepatic RNA was analyzed by Northern blot analysis using the indicated probes. (HL) Hepatic lipase. (B) Relative mRNA expression of FXRα1/α2 and FXRα3/α4 in fasted livers. Real-time PCR was used to identify the relative expression of FXRα1 + FXRα2 and FXRα3 + FXRα4 in the livers of mice either fed a chow diet or fasted for 24 h (n = 4 or 5 per group). The values are normalized to cyclophilin mRNA. (C) Ectopic expression of PGC-1α induces FXR expression. Murine primary hepatocytes were infected with adenovirus containing cDNA encoding either green fluorescent protein (GFP; Ad-GFP) or PGC-1α (Ad-PGC-1α) for 48 h, followed by treatment with either vehicle (DMSO) or the FXR ligand GW4064 (1 μM) for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated and mRNAs were identified by Northern blot assay. (D) PGC-1α differentially induces FXRα3/α4 expression in primary hepatocytes. FXR+/+ primary hepatocytes were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-PGC-1α for 48 h. Total RNA was isolated and real-time PCR was used to analyze the relative expression of FXRα1 + α2 and FXRα3 + α4. (E) cAMP differentially induces FXRα3/α4 expression in primary hepatocytes. Primary hepatocytes were treated with or without 1 mM 8-bromo-cAMP (cAMP) for 24 h. Northern blot or real-time PCR was used to analyze the indicated gene expression. (*) p < 0.05; (**) p < 0.01.

Four murine transcripts (FXRα1-FXRα4) are produced as a result of alternative splicing of exon 5 and the use of two alternative promoters that initiate transcription from either exon 1 or exon 3 (Zhang et al. 2003). To investigate whether the two murine FXR promoters are differentially activated by fasting, we used real-time PCR to analyze the relative hepatic expression of FXRα1 and FXRα2 (FXRα1/α2 in Fig. 1B) versus FXRα3 and FXRα4 (FXRα3/α4). The data of Figure 1B indicate that fasting results in a 2.1-fold increase in the level of FXRα3/α4 mRNAs, but in a statistically insignificant change in the levels of FXRα1/α2. These results suggest that fasting results in preferential activation of the 3′ (internal) FXR promoter relative to the 5′ promoter.

PGC-1α and cAMP induce FXR mRNA

The coordinate induction of PGC-1α and FXR mRNAs in response to fasting prompted us to investigate whether PGC-1α is involved in the transcriptional activation of the FXR gene. Primary hepatocytes, derived from either FXR+/+ or FXR-/- mice, were infected with adenovirus that expressed either green fluorescent protein (Ad-GFP, a negative control) or PGC-1α (Ad-PGC-1α; Fig. 1C). After 48 h, RNA was isolated and various mRNAs were quantitated by Northern blot analysis. The data of Figure 1C demonstrate that ectopic expression of PGC-1α resulted in a robust induction of FXR and SHP transcripts (Fig. 1C). In wild-type, but not in FXR-null hepatocytes, the SHP transcript was further induced by the FXR-specific ligand GW4064 (Fig. 1C). Using real-time PCR we also observed significant induction of SHP transcripts by GW4064 in wild-type hepatocytes that were infected with Ad-GFP (data not shown). These latter data are consistent with SHP being an FXR target gene (Goodwin et al. 2000; Lu et al. 2000). However, the finding that SHP mRNA was highly induced when PGC-1α was overexpressed in FXR-null hepatocytes indicates that SHP expression can also be induced by PGC-1α in an FXR-independent manner. Other mRNA levels, including PPARγ and HNF4α, were unchanged following PGC-1α overexpression (Fig. 1C; data not shown), suggesting that PGC-1α does not promote a global induction of gene expression.

Figure 1D shows that transcripts (FXRα3/α4) derived from the internal promoter, but not those derived from the 5′-promoter (FXRα1/α2), were induced following overexpression of PGC-1α in wild-type hepatocytes. Thus, the data of Figure 1, B and D, are consistent with the proposal that the two FXR promoters are differentially regulated in vivo in response to fasting, and in isolated cells in response to enhanced levels of PGC-1α.

cAMP has been shown to increase PGC-1α expression in rat primary hepatocytes (Yoon et al. 2001). Treatment of murine primary hepatocytes with dibutyryl cAMP significantly increased mRNA levels of PGC-1α (Fig. 1E, top), FXRα3/α4 and SHP (Fig. 1E, bottom), but had no effect on FXRα1/α2 expression (Fig. 1E, bottom). Taken together, these data suggest that cAMP may induce PGC-1α, which, in turn, enhances transcription of the FXR gene from the 3′-promoter.

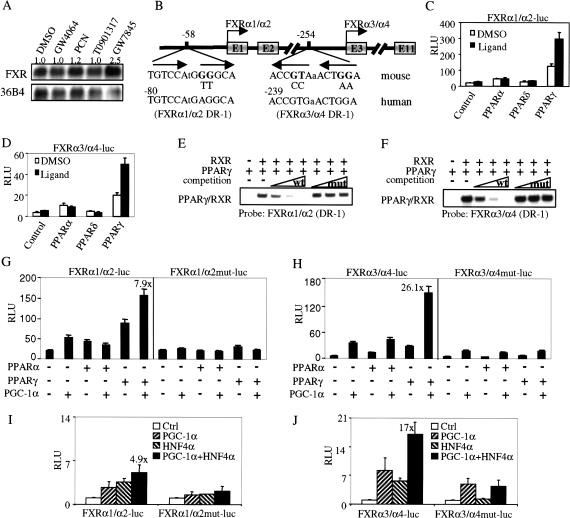

PGC-1α coactivates PPARγ and HNF4α to enhance FXR promoter activity

PGC-1α alone has low inherent transcriptional activity and is thought to function as a coactivator (Puigserver et al. 1999). To identify a potential transcriptional factor that is both bound to the FXR promoter and is activated by PGC-1α, we treated mouse primary hepatocytes with ligands for FXR, LXR, PXR, PPARα, PPARδ, or PPARγ; only the PPARγ-specific ligand GW7845 resulted in an increase in the FXR mRNA (Fig. 2A; data not shown). The two transcriptional start sites (exon 1 and exon 3 of the FXR gene) are separated by 26.6 kb (Fig. 2B). Analysis of the nucleotides upstream of exons 1 and 3 identified a putative PPARE (DR-1) at -58 bp to -46 bp or -254 bp to -242 bp, respectively (Fig. 2B). Both putative PPAREs are conserved in the two human FXR promoters (Fig. 2B). Reporter genes under the control of either the 5′ (FXRα1/α2) or 3′ (FXRα3/α4) FXR promoters were cotransfected into CV-1 cells together with plasmids encoding RXR and PPARα, PPARδ, or PPARγ (Fig. 2C,D). The data of Figure 2, C and D, show that both FXR promoter-reporter genes, that contained the putative PPAREs, were robustly induced by PPARγ and that the induction was potentiated by the PPARγ-specific ligand GW7845. In contrast, both FXR reporter genes were weakly activated by PPARα and unaffected by PPARδ in the absence or presence of specific ligands (Fig. 2C,D). These latter results using the FXR promoter-reporter constructs are consistent with the observation that only the PPARγ ligand induced the endogenous FXR mRNA (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

PGC-1α coactivates PPARγ and HNF4α to enhance FXR gene transcription. (A) PPARγ ligand induces FXR expression. Mouse primary hepatocytes were treated for 24 h with either vehicle (DMSO) or ligands for FXR (GW4064, 1 μM), PXR (PCN, 10 μM), LXR (T0901317, 1 μM), or PPARγ (GW7845, 1 μM). Total RNA was used for Northern blot assay. (B) Schematic representation of the 5′-end of the FXR gene showing the two FXR promoters and the nucleotides corresponding to the two DR-1 elements. FXRα1/α2 and FXRα3/α4 mRNAs are the products of transcription initiated from exon 1 or exon 3, respectively. Exon 1 is 26.6 kb upstream of exon 3. The sequences of DR-1 elements, and the incorporated mutations, are shown. The corresponding sequences of DR-1 elements in the promoters of the human FXR gene are also shown. (C,D) Activation of FXR promoters by PPARs. CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with either the FXR promoter-reporter constructs pGL3-FXRα1/α2-luc or pGL3-FXRα3/α4-luc together with PPARα, PPARδ, or PPARγ. The cells were treated with either vehicle or corresponding ligands (PPARα, 1 μM GW7847; PPARδ, 1 μM GW2433; PPARγ, 1 μM GW7845) for 36 h. Luciferase activity was analyzed and normalized with β-galactosidase activity. The values represent three independent experiments. (E,F) PPARγ/RXR binds to the DR-1 elements in both FXR promoters. Electrophoretic mobility-shift assays were performed using in vitro transcribed/translated receptors and radiolabeled FXRα1/α2 (E) or FXRα3/α4 (F) probes. For competition experiments, excess unlabeled competitor DNA, containing wild-type or mutant DR-1 sequences (B), was used at 20×, 100×, and 500×, respectively. (G,H) PGC-1α coactivates PPARγ to enhance FXR transcription via a DR-1 element. CV-1 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding PPARα, PPARγ, or PGC-1α together with either pGL3-FXRα1/α2-luc and pGL3-FXRα1/α2mut-luc (G) or pGL3-FXRα3/α4-luc and pGL3-FXRα3/α4mut-luc (H). Cells were incubated for 36 h in the presence or absence of specific PPAR ligands prior to determination of the luciferase activity. Values, normalized to β-galactosidase activity, are the means (±SE) of three experiments. (I,J) PGC-1α coactivates HNF4α to enhance FXR transcription via a DR-1 element. CV-1 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding PGC-1α or HNF4α together with FXR promoters as described in G and H. These values represent three independent experiments.

To determine whether PPARγ/RXR can bind to the putative PPREs, electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed that used radiolabeled oligonucleotides containing the DR-1 element from either the 5′-promoter (FXRα1/α2; Fig. 2E) or the internal promoter (FXRα3/α4; Fig. 2F) of the FXR gene. Both radiolabeled probes formed a shifted complex only when incubated with both PPARγ and RXR (Fig. 2E,F, lane 2). The formation of the complex was competed away by the addition of unlabeled probes, but not by the addition of unlabeled probes containing mutations in the DR-1 element (Fig. 2E,F). Thus, these studies identify a functional PPARE in each of the two proximal promoters of the murine FXR gene.

PGC-1α was originally identified as a coactivator for PPARγ (Puigserver et al. 1998). PPARγ is induced during fasting (Fig. 1A). The studies described above suggest that PGC-1α potentiates the transcription of the FXR gene, possibly via activation of PPARγ. To test this proposal, CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with either FXRα1/α2 or FXRα3/α4 promoter-reporter genes together with plasmids encoding PGC-1α, PPARγ, or PPARα. The data of Figure 2, G and H, show that PGC-1α alone activated the 5′ and 3′ FXR promoter-reporter genes by 2.5- and 6.1-fold, respectively. However, induction was enhanced by 7.9- and 26.1-fold in the presence of both PGC-1α and PPARγ (Fig. 2G,H). Thus, the FXRα3/α4 promoter is activated by PPARγ plus PGC-1α to a greater extent than the FXRα1/α2 promoter (Fig. 2H vs. Fig. 2G). Mutation of the DR-1 elements in either promoter attenuated the stimulatory effect produced by both PGC-1α and PPARγ (Fig. 2G,H). The finding that the FXRα3/α4 mutant promoter is activated threefold by PGC-1α (Fig. 2H, right panel) suggests that PGC-1α also activates other factors that modulate transcription of the FXR gene. In contrast to the data with PPARγ, activation of the FXR reporter genes by PPARα was unaffected by PGC-1α (Fig. 2G,H). These data suggest a mechanism by which overexpression of PGC-1α in hepatocytes produces a differential induction of the FXRα3/α4 versus FXRα1/α2 transcripts as a result of activation of PPARγ (Fig. 1D).

HNF4α is abundantly expressed in the liver and is induced by fasting (Fig. 1A). PGC-1α has also shown to be a coactivator for HNF4α (Yoon et al. 2001). To investigate whether HNF4α could also activate FXR gene transcription via the DR-1 elements, transient transfection experiments were performed (Fig. 2I,J). HNF4α activated wild-type but not mutated FXR promoters. However, in the presence of both PGC-1α and HNF4α, the internal (FXRα3/α4) promoter was induced to a much higher level compared with the 5′ (FXRα1/α2) promoter (17-fold vs. 4.9-fold). Taken together, these data suggest that the differential induction of FXR transcripts by PGC-1α may be achieved by the activation of HNF4α and/or PPARγ.

PGC-1α coactivates FXR to enhance FXR-target gene promoter activity

The findings that ectopic expression of PGC-1α in FXR+/+ hepatocytes induced both FXR and the FXR target gene SHP, and that the induction of SHP was further potentiated by an FXR-specific ligand (Fig. 1C), suggest that PGC-1α may coactivate FXR per se. To test this hypothesis, we transiently transfected cells with luciferase reporter genes under the control of the promoters derived from the murine BSEP or I-BABP genes together with plasmids that express FXR or PGC-1α. Both BSEP and I-BABP are well-characterized FXR target genes (Grober et al. 1999; Makishima et al. 1999; Ananthanarayanan et al. 2001). BSEP is known to be activated by all four FXR isoforms, whereas I-BABP is known to be preferentially activated by FXRα2 or FXRα4, the FXR isoforms that do not contain the four amino acid insert in their hinge regions (Zhang et al. 2003).

As expected, FXRα2 and FXRα4 activated the I-BABP promoter ∼10-fold in the presence of FXR ligand GW4064 (Fig. 3A; Zhang et al. 2003). In the absence of FXR, PGC-1α had no effect on the I-BABP promoter activity (Fig. 3A). However, coexpression of PGC-1α together with FXRα2 or FXRα4 resulted in a remarkable 250- to 300-fold activation (Fig. 3A). In contrast, FXRα1 or FXRα3, the isoforms with the four amino acid insert in their hinge regions, cannot activate the I-BABP promoter even in the presence of PGC-1α (Fig. 3A). In addition, the I-BABP promoter containing a mutant FXRE was unresponsive to all FXR isoforms even in the presence of PGC-1α (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that the transcriptional activation of FXR target genes, such as I-BABP, by PGC-1α is dependent on FXR and an intact FXRE.

Figure 3.

PGC-1α coactivates all FXR isoforms to enhance FXR target gene transcription. (A-C) HepG2 cells were transiently transfected in triplicate with the indicated I-BABP or BSEP promoter-reporter gene together with a specific FXR isoform and PGC-1α. The cells were treated with vehicle or GW4064 (1 μM). After 36 h the cells were lysed and the luciferase activity was determined after being normalized to β-galactosidase activity. These values represent the means (±SE) of three experiments.

To determine whether PGC-1α also activates FXRα1 and FXRα3, we used a BSEP promoter-reporter construct because all four FXR isoforms have been shown to activate the murine BSEP gene to a similar degree (Zhang et al. 2003). As shown in Figure 3C, all four FXR isoforms activated the BSEP promoter to similar levels and, in each case, this activation was robustly potentiated by PGC-1α. Taken together, these data demonstrate that PGC-1α highly activates all four FXR isoforms. Nonetheless, the specificity of gene activation in response to the different FXR isoforms is unaffected by PGC-1α.

PGC-1α interacts with the DNA-binding domain of FXR

To investigate the mechanism(s) by which PGC-1α activates FXR, we performed a series of in vitro protein-binding studies to determine whether PGC-1α interacts with FXR. Full-length as well as 5′ or 3′ deletion fragments of FXR were in vitro translated in the presence of 35S-methionine and incubated with glutathione S-transferase (GST)-PGC-1α (amino acids 1-400) fusion protein. Figure 4A shows both a graphical representation of the domain structure of FXRα3 and a summary of the results obtained when the indicated fragments of FXRα3 were incubated with GST-PGC-1α (1-400). The data from studies with different FXR isoforms and different fragments of FXRα3 are presented in Figure 4B-D.

Figure 4.

PGC-1α physically interacts with FXR in vitro and in cells. (A) Schematic representation of the domain structures of FXRα3 and the summary of the results to determine an interaction between PGC-1α (1-400) and various fragments of FXRα3. The domain structures of FXRα3 are shown (top). Interactions between PGC-1α (1-400) and the indicated fragments of FXRα3 are represented by + or - (right). (B) Mapping of the 5′ interaction domain of FXR with PGC-1α (1-400). 35S-labeled proteins corresponding to each of the four full-length FXR isoforms or 5′ deletions of FXRα3 or FXRα4 were incubated with GST-PGC-1α (1-400) in the presence of glutathione beads as described in Materials and Methods. The bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by autoradiography. (C) Mapping of the 3′ interaction domain of FXR with PGC-1α (1-400). The indicated N-terminal fragments of FXRα3 were in vitro labeled with 35S-methionine and used to determine the interaction with GST-PGC-1α (1-400), as described in B. (D) The DBD of FXR interacts directly with PGC-1α. 35S-labeled full-length PGC-1α protein was used to determine the interaction with the DBD or DBD plus the four amino acid insert (MYTG) of FXR. (E) Mapping the interaction domain of PGC-1α with FXR. 3′ deletions of PGC-1α with or without the mutation of the LXXLL motif were in vitro labeled with 35S-methionine and used to test interaction with the DBD of FXR. (F) FXR ligand has no effect on the interaction between FXR and PGC-1α. 35S-labeled, full-length FXRα1-4 were incubated with PGC-1α (1-400) in the presence or absence of GW4064 (1 μM). The assay was performed as described in B. (G) PGC-1α interacts with FXR in cells. CV-1 cells were transfected with CMX-Flag-PGC-1α and CMX-FXR plasmids, as indicated. After 48 h, whole-cell lysates were prepared and incubated with anti-Flag antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Western blot, using an anti-FXR antibody.

The data show that PGC-1α interacts with the full-length forms of each of the four FXR isoforms (Fig. 4B, lanes 1-4) and with fragments that contain the intact DNA-binding domain (Fig. 4B, lanes 5,6; Fig. 4C, lanes 7-9). However, FXR fragments that contained either the ligand-binding domain (amino acids 269-488) or the LBD plus the hinge region and only part of the DBD (amino acids 190-488 or 214-488) failed to interact with PGC-1α (Fig. 4B, lanes 7-10). GST alone did not interact with FXR (Fig. 4C, lanes 4,5). These data suggest that the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of FXR might be required for the interaction with PGC-1α.

To test whether the DBD of FXR interacts with PGC-1α, DBD +/- the four amino acid insert (MYTG) were fused to GST as bait protein and incubated with full-length 35S-methionine-labeled PGC-1α. The DBD or DBD + MYTG interacted equally well with full-length PGC-1α (Fig. 4D). These data suggest that the DBD of FXR is required and sufficient to interact with PGC-1α.

To map the region of PGC-1α that interacts with FXR, we used the GST-FXR(DBD) fusion protein and 35S-labeled PGC-1α fragments with a series of 3′ deletions that contain either the wild-type or mutated LXXLL motif (amino acids 142-146). This leucine-rich motif has been shown to be required for the binding of PGC-1α to PPARα, HNF4α, and ERα (Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003). Figure 4E shows that the DBD of FXR strongly interacts with PGC-1α (1-400) containing either a wild-type or mutant LXXLL motif (36% pull down). In contrast, there was little interaction (<0.5%) with PGC-1α, amino acids 1-180 (Fig. 4E). We conclude that the DBD of FXR interacts with amino acids 180-400 of PGC-1α. PPARγ and NRF-1 have also been shown to interact with this same region (Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003).

In some, but not all cases, recruitment of coactivators to nuclear receptors is dependent on the presence of receptor-specific ligands (Glass et al. 1997; Shibata et al. 1997). To investigate whether an FXR ligand affects the interaction between PGC-1α and FXR, the pull-down assay was performed in the absence or presence of GW4064, an FXR-specific ligand. Figure 4F shows that the interaction of PGC-1α with each of the four FXR isoforms was not affected by GW4064, suggesting that the interaction between PGC-1α and FXR is ligand-independent.

To investigate whether PGC-1α and FXR interact in cells, we isolated whole-cell lysates following transient transfection of CV-1 cells with plasmids encoding Flag-tagged PGC-1α and specific FXR isoforms. Immunoprecipitation with an anti-Flag antibody followed by Western blot assays using anti-FXR antibody demonstrates that PGC-1α interacts with all four FXR isoforms (Fig. 4G, lanes 2-5). In contrast, no FXR protein was precipitated when the cells were transfected with PGC-1α alone (Fig. 4G, lane 1). Taken together, the data demonstrate that the region containing amino acids 180-400 of PGC-1α interacts directly with the DBD of FXR in a ligand-independent manner.

Fasting specifically decreases plasma triglyceride levels

The finding that FXR-/- mice exhibit elevated plasma triglyceride levels compared with their wild-type littermates (Sinal et al. 2000) suggests that FXR may play an important role in triglyceride metabolism. The findings that fasting induces mRNAs for both PGC-1α (Yoon et al. 2001) and FXR (Fig. 1A) and that PGC-1α interacts directly with FXR to increase FXR target gene transcription (Figs. 3, 4) have led us to hypothesize that fasting might decrease plasma triglyceride levels through an FXR-dependent process. Consistent with this hypothesis, fasting was associated with a significant decrease in plasma triglyceride levels in both male and female FXR+/+ mice but a significant increase in these lipids in FXR-/- mice (Fig. 5). The differential effect of FXR geno-type on triglyceride levels in response to fasting is relatively specific because both plasma total cholesterol, free fatty acids, and HDL cholesterol levels increased, or were unaffected, in both FXR+/+ and FXR-/- mice (Fig. 5C,D; data not shown). These data demonstrate that the decrease in plasma triglyceride levels in response to fasting is dependent on FXR.

Figure 5.

The change in plasma triglyceride levels in response to fasting is dependent on the FXR genotype. (A,B) Fasting decreases plasma triglyceride levels. Male (A) and female (B) FXR+/+ or FXR-/- mice (n = 4 or 5 per group) were either fed a chow diet or fasted for 24 h. Blood samples were collected and plasma triglyceride levels (mean ± SE) were determined. (C,D) Fasting increases total plasma cholesterol and plasma free fatty acids. Plasma total cholesterol (C) or free fatty acids (D; mean ± SE) are shown for the same mice. (*) p < 0.05; (**) p < 0.01.

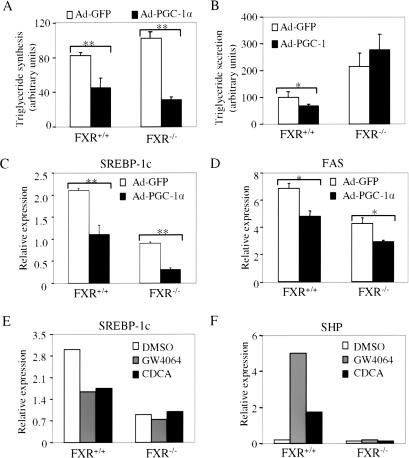

PGC-1α modulates triglyceride synthesis and secretion

Hepatic PGC-1α levels have been shown to increase in response to fasting (Fig. 1A; Yoon et al. 2001). To investigate whether the decrease in plasma triglyceride levels that occurs in fasted wild-type mice (Fig. 5A,B) might be mediated by the PGC-1α/FXR pathway, we infected mouse primary hepatocytes with adenovirus expressing GFP or PGC-1α. After 48 h, cells were incubated for an additional 2 h in media containing 14C-palmitic acid prior to isolation of radiolabeled lipids. The data show that ectopic expression of PGC-1α decreased triglyceride synthesis in both normal and FXR-null hepatocytes (Fig. 6A). In contrast, PGC-1α expression reduced triglyceride secretion in normal but not in FXR-null cells (Fig. 6B). In addition, the data of Figure 6B suggest that FXR-/- hepatocytes secrete twofold to threefold more triglyceride than FXR+/+ hepatocytes (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

PGC-1α and FXR regulate triglyceride synthesis and secretion. (A) Ectopic expression of PGC-1α decreases triglyceride synthesis in primary hepatocytes. Wild-type and FXR-null primary hepatocytes were infected with adenovirus expressing GFP or PGC-1α. After 48 h, 14C-palmitic acid was added to the media. After an additional 2 h, the media and hepatocytes were separated and the radioactive triglyceride levels were determined, as described in Materials and Methods. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3). (B) Ectopic expression of PGC-1α decreases triglyceride secretion in an FXR-dependent manner. FXR+/+ or FXR-/- primary hepatocytes were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-PGC-1α for 48 h and then incubated with 14C-palmitic acid for 2 h, as described in A. The radioactive triglyceride in the media was determined and the values were shown, mean ± SE (n = 3). (C,D) Ectopic expression of PGC-1α decreases SREBP-1c and FAS expression. Primary hepatocytes were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-PGC-1α for 48 h. Real-time PCR was used to analyze the relative expression of SREBP-1c and fatty acid synthase (FAS). (E,F) Activation of FXR decreases SREBP-1c expression. Primary hepatocytes were treated with FXR ligand GW4064 (1 μM) or CDCA (100 μM) for 24 h. Real-time PCR was used to analyze the relative expression of SREBP-1c and SHP expression. (*) p < 0.05; (**) p < 0.01.

Overexpression of PGC-1α in wild-type and FXR-null hepatocytes also resulted in a decrease in the SREBP-1c and fatty acid synthase mRNA levels (Fig. 6C,D). Because SREBP-1c regulates multiple genes involved in fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis (Horton et al 2002), these data provide a mechanism by which PGC-1α overexpression inhibits triglyceride synthesis in both cell types (Fig. 6A).

Because PGC-1α can activate FXR (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4), we are interested in whether activation of FXR may also decrease SREBP-1c expression. Consequently, wild-type and FXR-null primary hepatocytes were treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or FXR ligands. Treatment with either GW4064 or CDCA decreased SREBP-1c mRNA levels in wild-type, but not in FXR-null hepatocytes (Fig. 6E). In contrast, the FXR target gene SHP was induced by FXR ligands only in wild-type hepatocytes (Fig. 6F). These data demonstrate that activation of FXR decreases SREBP-1c mRNA expression. Taken together, the data suggest that PGC-1α may decrease SREBP-1c expression and triglyceride synthesis via both FXR-dependent and -independent pathways.

Discussion

PGC-1α has been shown to regulate a number of biological pathways linked to energy production and utilization (Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003). One major function of PGC-1α appears to be the stimulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis in response to fasting (Yoon et al. 2001). Here we demonstrate that PGC-1α has unexpected and novel roles in regulating both FXR expression and FXR activation. Such changes lead to alterations in hepatic gene expression and triglyceride metabolism (Fig. 7). We also demonstrate that under conditions in which hepatic PGC-1α levels are increased (fasting, ectopic expression of PGC-1α, or elevated cellular cAMP levels), there is preferential activation of the 3′ (internal) promoter of the murine FXR gene; the result is increased mRNA levels of FXRα3 and FXRα4 as compared with FXRα1 and FXRα2 (Fig. 1B,D,E). The relative steady-state expression of FXRα1-4 in different murine or human tissues is known to vary (Huber et al. 2002; Zhang et al 2003). However, the present report provides the first evidence that the two FXR promoters can be differentially regulated. We also demonstrate that transcriptional activation of FXR promoter-reporter genes is potentiated by coexpression of PGC-1α and PPARγ. These data are consistent with the presence of a PPARE (DR-1 element) in the FXR promoters, induction of the endogenous FXR mRNA by GW7845 (a PPARγ-specific ligand), and induction of hepatic PPARγ mRNA levels in response to fasting (Figs. 1A, 2A-H). Thus, these data provide novel evidence that links PPARγ and FXR to changes in hepatic lipid metabolism.

Figure 7.

Model for PGC-1α to activate FXR and regulate triglyceride metabolism. PGC-1α, PPARγ, and HNF4α mRNAs are induced after a prolonged fast. PGC-1α coactivates PPARγ and/or HNF4α bound to a DR-1 element in the FXR promoter, to induce FXR mRNA expression. In addition, PGC-1α interacts directly with FXR to enhance transcription of FXR target genes. Activation of FXR target genes by PGC-1α and FXR results in a decrease in SREBP-1c expression and in increased expression of genes involved in triglyceride metabolism and clearance. On the other hand, PGC-1α may also repress SREBP-1c expression in an FXR-independent manner. The decrease in SREBP-1c expression may reduce triglyceride synthesis/secretion and lower plasma triglyceride levels. The decrease in triglyceride synthesis in the liver may reduce storage of fatty acids and increase fatty acid β-oxidation to meet the normal energy demands during fasting.

In addition to PPARγ, our data also demonstrate that HNF4α may bind to these DR-1 elements and activate FXR gene transcription by a process that is potentiated by PGC-1α (Fig. 2I,J). Interestingly, in the presence of PGC-1α, HNF4α or PPARγ preferentially activates the internal (FXRα3/α4) promoter. This may explain why PGC-1α preferentially induces FXRα3/α4 transcripts in primary hepatocytes. Because HNF4α is abundantly expressed in the liver and is induced by fasting (Fig. 1A), we propose that HNF4α and PGC-1α may together play a major role in mediating the activation of FXR gene transcription in response to fasting. Nonetheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that other transcription factors also bind to the DR-1 element and activate FXR transcription.

PPARα is enriched in the liver, and its level is further induced in response to fasting (Kersten et al. 1999). Because ligand-activated PPARα also activates FXR-promoter reporter genes, albeit by a process that is unaffected by PGC-1α (Fig. 2C,D,G,H), this member of the PPAR nuclear family may also have a role in regulating FXR expression. Additional studies will be required to determine whether the hypotriglyceridemic effects of PPARα ligands, such as fibrates, involve FXR.

PGC-1α has previously been shown to interact with either the hinge region (Puigserver et al. 1998) or the AF2 domain (Tcherepanova et al. 2000) of nuclear receptors or other transcription factors (Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003). The requirement for the LXXLL motif in these interactions has been shown to be variable (Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003). Using 5′ and 3′ deletions of FXR proteins and 3′ deletions of PGC-1α fragments, we demonstrate that the region containing amino acids 180-400 of PGC-1α interacts directly with the DNA-binding domain of all four FXR isoforms in a ligand-independent manner (Fig. 4). To our knowledge, PGC-1α has not previously been shown to interact directly with the DBD of nuclear receptors. Not surprisingly, PGC-1α activates all four FXR isoforms (Fig. 3C), because the amino acid sequences in their DBDs are identical (Zhang et al. 2003).

The combined effect of the changes in PGC-1α-induced FXR gene expression and FXR-activated target gene expression in normal mice is to cause a decrease in both plasma triglyceride levels and in hepatic triglyceride synthesis and secretion (Figs. 5, 6, 7). In contrast, neither plasma triglyceride levels nor hepatic triglyceride secretion decline in FXR-null mice or hepatocytes (Figs. 5, 6). These data provide the genetic evidence that links PGC-1α to FXR and to the control of triglyceride metabolism. We hypothesize that the consequence of the decrease in triglyceride biosynthesis/secretion in response to PGC-1α and FXR is to reduce the energy storage of fatty acids. Such changes may also complement the increased fatty acid β-oxidation that occurs during fasting, so as to meet normal energy demands. Taken together, our data provide a molecular network to explain how fasting, PGC-1α and FXR together regulate triglyceride metabolism (Fig. 7).

FXR has been shown to play an important role in maintaining bile acid, cholesterol, and lipoprotein metabolism. In FXR-deficient mice, plasma triglyceride levels are elevated compared with wild-type littermates. In addition, previous reports have shown that activation of FXR by drugs or bile acids lowers plasma triglyceride levels in wild-type rodents (Maloney et al. 2000; Kast et al. 2001) but has no effect in FXR-null mice (Kast et al. 2001). However, the mechanism by which FXR regulates plasma triglyceride levels has not been clearly established, despite the fact that several FXR target genes (apoC-II, phospholipid transfer protein, syndecan-1) that regulate lipoprotein metabolism have been identified (Edwards et al. 2000; Anisfeld et al. 2003). After injection with tyloxapol (an inhibitor of VLDL catabolism), plasma VLDL triglyceride levels in FXR-/- mice increased dramatically compared with those in FXR+/+ mice, suggesting that FXR-/- mice might secrete more triglycerides/VLDL than normal mice (Lambert et al. 2003). Consistent with this hypothesis, our in vitro experiments using 14C-labeled palmitic acid indicate that FXR-/- hepatocytes secreted twofold more radiolabeled triglyceride than FXR+/+ hepatocytes (Fig. 6B).

The finding that mRNA levels of SREBP-1c and FAS are reduced following overexpression of PGC-1α provides a mechanism to explain the decrease in fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis in both wild-type and FXR-null cells (Fig. 6C,D). Based on the observation that activation of FXR decreases SREBP-1c mRNA levels in wild-type cells (Fig. 6E), we conclude that PGC-1α decreases SREBP-1c mRNA levels through both FXR-dependent and FXR-independent pathway. Because SREBP-1 has been shown to activate multiple genes involved in fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis (Edwards et al. 2000; Horton et al. 2002), this decrease in SREBP-1c expression might provide the molecular link between PGC-1α, FXR, and fatty acid synthesis.

In summary, we have established a new link between PGC-1α, FXR, and triglyceride metabolism in the liver. We hypothesize that the decrease in triglyceride production/secretion following activation of PGC-1α and FXR during fasting will provide additional fatty acids for β-oxidation, to generate more energy. Such changes would parallel the increase in gluconeogenesis that occur under the same physiological conditions (Yoon et al. 2001; Puigserver and Spiegelman 2003). In addition, plasma triglyceride levels have been identified as an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease (Cullen 2000; Forrester 2001). The finding that PGC-1α decreases triglyceride production and secretion via FXR in the liver may allow for the development of novel liver-selective drugs that target either PGC-1α and/or FXR as a treatment for hypertriglyceridemic patients.

Materials and methods

Materials

The expression plasmids CMX-FXRα1, CMX-FXRα2, CMXFXRα3, and CMX-FXRα4, and the pGL3-BSEP promoter plasmid have been described elsewhere (Zhang et al. 2003). FXR constructs with 5′ deletions or 3′ deletions, or PGC-1α constructs with 3′ deletions, were generated by PCR and subcloned into the pCMX expression vector. CMX-PGC-1α(1-400mut) or CMX-PGC-1α(1-180mut) was created by mutagenesis of the LXXLL motif (amino acids 142-146) into LXXAA using the Quick-Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). CMX-HNF4α was generated by cloning the coding region of HNF4α into pCMX vector. GST-FXR(DBD) and GSTFXR(DBD+4aa) were created by cloning the DNA binding domain (DBD) of FXR or DBD plus a four amino acid insert motif (MYTG) into the pGEX-4T1 vector. Mouse FXR promoter reporters pGL3-FXRα1/α2-luc and pGL3-FXRα3/α4-luc were constructed by cloning the fragments -1020 to +94 or -1103 to +37, relative to the transcriptional start sites of exon 1 or 3, respectively, into pGL3. The constructs pGL3-FXRα1/α2mut-luc and pGL3-FXRα3/α4mut-luc were created by mutating 2 or 4 bp of the DR-1 elements. mI-BABP1042-luc and I-BABP142mut-luc promoter plasmids were kindly provided by David Mangelsdorf (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; Makishima et al. 1999). Plasmids GST-PGC-1α(1-400) and pcDNA-PGC-1α have been described elsewhere (Puigserver et al. 1998, 1999; Lin et al. 2002a). CMX-PPARα, CMX-PPARγ, and pBabe-PPARδ were kindly provided by Peter Tontonoz (University of California, Los Angeles). Recombinant adenovirus Ad-GFP and Ad-PGC-1α have been described (Lehman et al. 2000). Synthetic ligands, including GW4064 (FXR), GW7447 (PPARα), GW2433 (PPARδ), and GW7845 (PPARγ) are gifts from Tim Willson (GlaxSmithKline).

Animal experiments

Eight- to 10-week-old male and female FXR-null and their wild-type C57BL/6J littermates (Sinal et al. 2000) were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility with 12-h light/12-h dark cycle and either fed standard rodent chow diet or fasted for 24 h. Fasting started 3 h prior to the dark cycle and ended the following day 3 h prior to the next dark cycle. Blood samples were collected for lipid assay, and the livers were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at -80°C until analyzed.

RNA analysis and real-time PCR

Total RNA from tissue or cells was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Then 10 μg of total RNA was denatured, electrophoresed, transferred to a nylon membrane, and probed with the indicated cDNA probes. For analysis of relative mRNA expression of FXRα1/α2, FXRα3/α4, SREBP-1c, and FAS, real-time PCR was performed using corresponding primes and probes as described (Zhang et al. 2003). The sequences of primers and probes for SREBP-1c and FAS are available upon request.

Transfection assay

CV-1 and HepG2 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 U/mL penicillin G, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate in a 5% CO2/37°C incubator. Transient transfections were performed in a 48-well plate. Briefly, 5 ng of CMX-RXR, 100 ng of reporter plasmid, and 50 ng of pCMX-β-gal, together with 50 ng of CMX-FXR, CMX-PPARs, CMXHNF4α, and/or pcDNA-PGC-1α, were cotransfected in CV-1 or HepG2 cells using the MBS Mammalian Transfection kit (Stratagene). The cells were treated with vehicle (Me2SO) or indicated ligands in superstripped FBS (HyClone) for 36 h. Luciferase activity was assayed and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Each transfection was performed in triplicate.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSA was performed essentially as described (Zhang et al. 2003). Briefly, in vitro translated nuclear receptors and 32P endlabeled oligonucleotide were incubated in a buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 6% glycerol, 100 μg/mL poly(dI-dC), and 0.3 mg/mL BSA. For competition experiments, an excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide was added at the indicated concentration.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Flag-tagged PGC-1α and/or FXR expression plasmids were transiently transfected into CV-1 cells using the MBS Mammalian Transfection kit. After 48 h, whole-cell lysates were prepared and subjected to an overnight incubation with a monoclonal antibody to Flag conjugated to agarose beads (Sigma). The immunoprecipitates were washed extensively, separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunodetection using anti-FXR antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech).

Protein interaction assays

GST and GST fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21, pLysS) and purified on beads containing glutathione. 35S-labeled FXR proteins were produced in vitro using TNT-T7 coupled reticulocytes (Promega). Fusion protein (300 ng) was mixed with 5-7 μL of 35S-labeled protein in a binding buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 6% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.05% Triton X-100. The binding reaction was gently rotated for 1 h at 4°C, and the beads were then extensively washed with PBS and resuspended in SDS sample buffer. After electrophoresis, the 35S-labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography.

Primary hepatocytes and adenovirus infection

Primary hepatocytes were isolated and cultured as described (Berry and Friend 1969), with minor modifications. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with nembutal (50 mg/kg). After cannulation of the portal vein, the liver was perfused with a PBS-EDTA chelating solution (0.1 g of glucose and 19mg of Na-EDTA per 100 mL of PBS) for 5 min, followed by perfusion for 6 min with a PBS-collagenase (GIBCO) solution (0.1 g of glucose and 50 mg of collagenase per 100 mL of PBS). Hepatocytes were dispersed, filtered through gauze, and washed thrice in Hepato-STIM hepatocyte culture media (BD Bioscience). The media were serum-free, but contained insulin and dexamethasone. Viability, determined by trypan blue exclusion, was >95%. The hepatocytes were plated at a density of 6 × 106 cells/10-cm plate and cultured in Hepato-STIM hepatocyte culture media for 48 h prior to being used in the various experiments. For adenovirus infection, the hepatocytes were infected for 48 h with adenovirus carrying cDNA encoding either green fluorescent protein (GFP; Ad-GFP) or PGC-1α (Ad-PGC-1α) at an m.o.i. of 5, followed by the indicated treatments.

Lipid analysis

Lipids were analyzed by the Lipid and Lipoprotein Laboratory at the University of California Los Angeles, which is certified by the CDC National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Lipid Standardization Program. Briefly, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and unesterified fatty acids were determined by enzymatic, colorimetric methods as described previously (Warnick 1986). Free plasma glycerol concentrations were also determined and used to correct the triglyceride values. The HDL cholesterol is derived from the measurement of the supernatant following the precipitation of apoB-containing lipoproteins with heparin and MnCl2 (Puppione and Charugundla 1994). All assays were performed in triplicate with three external control samples with known analytic concentrations included in each assay to ensure accuracy.

Rates of triglyceride synthesis and secretion

Primary hepatocytes were cultured under 95% O2/5% CO2 in Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing 5.5 mM glucose, 3% BSA, 1 mM palmitic acid, and [U-14C]-palmitic acid at a final specific activity of 1.25 × 106 dpm/μmole of palmitate (∼5 × 106 dpm/2 mL of media). After 2 h, the media was collected for lipid extraction. The hepatocytes were washed thrice with cold PBS and then collected for lipid extraction. The major lipid classes (phospholipids, cholesterol, unesterified fatty acids, triglycerides, and cholesteryl esters) were extracted (Folch et al. 1957) and separated by thin layer chromatography, and the radioactivity incorporated into the triglyceride fraction was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry as described (Castellani et al. 1991).

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed student's t-test was used to calculate P-values.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Spiegelman, D. Mangelsdorf, P. Tontonoz, and T. Willson for providing plasmids and reagents and H. Woebern, P. Tontonoz, R. Davis, and the members of the Edwards lab for critical comments. We thank Chinwe Okoye for excellent technical assistance. Y. Zhang is a recipient of an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL30568 and HL68445 (to P.A.E.) and a grant from the Laubisch Fund (to P.A.E.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1138104.

References

- Ananthanarayanan M., Balasubramanian, N., Makishima, M., Mangelsdorf, D.J., and Suchy, F.J. 2001. Human bile salt export pump promoter is transactivated by the farnesoid X receptor/bile acid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 28857-28865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisfeld A.M., Kast-Woelbern, H.R., Meyer, M.E., Jones, S.A., Zhang, Y., Williams, K.J., Willson, T., and Edwards, P.A. 2003. Syndecan-1 expression is regulated in an isoform-specific manner by the farnesoid-X receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 20420-20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M.N. and Friend, D.S. 1969. High-yield preparation of isolated rat liver parenchymal cells: A biochemical and fine structural study. J. Cell Biol. 43: 506-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani L.W., Wilcox, H.C., and Heimberg, M. 1991. Relationships between fatty acid synthesis and lipid secretion in the isolated perfused rat liver: Effects of hyperthyroidism, glucose and oleate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1086: 197-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen P. 2000. Evidence that triglycerides are an independent coronary heart disease risk factor. Am. J. Cardiol. 86: 943-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards P.A., Tabor, D., Kast, H.R., and Venkateswaran, A. 2000. Regulation of gene expression by SREBP and SCAP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1529: 103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards P.A., Kast, H.R., and Anisfeld, A.M. 2002. BAREing it all: The adoption of LXR and FXR and their roles in lipid homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 43: 2-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Lees, M., and Sloane-Stanley, G.H. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226: 497-509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman B.M., Goode, E., Chen, J., Oro, A.E., Bradley, D.J., Perlmann, T., Noonan, D.J., Burka, L.T., McMorris, T., Lamph, W.W., et al. 1995. Identification of a nuclear receptor that is activated by farnesol metabolites. Cell 81: 687-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester J.S. 2001. Triglycerides: Risk factor or fellow traveler? Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 16: 261-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass C.K. 1994. Differential recognition of target genes by nuclear receptor monomers, dimers, and heterodimers. Endocr. Rev. 15: 391-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass C.K., Rose, D.W., and Rosenfeld, M.G. 1997. Nuclear receptor coactivators. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9: 222-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin B., Jones, S.A., Price, R.R., Watson, M.A., McKee, D.D., Moore, L.B., Galardi, C., Wilson, J.G., Lewis, M.C., Roth, M.E., et al. 2000. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Mol. Cell 6: 517-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober J., Zaghini, I., Fujii, H., Jones, S.A., Kliewer, S.A., Willson, T.M., Ono, T., and Besnard, P. 1999. Identification of a bile acid-responsive element in the human ileal bile acid-binding protein gene. Involvement of the farnesoid X receptor/9-cis-retinoic acid receptor heterodimer. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 29749-29754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J.D., Goldstein, J.L., and Brown, M.S. 2002. SREBPs: Activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J. Clin. Invest. 9: 1125-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R.M., Murphy, K., Mian, B., Link, J.R., Cunningham, M.R., Rupar, M.J., Cunyuzlu, P.L., Haws, T.F., Kassam, A., Powell, F., et al. 2002. Generation of multiple farnesoid-X-receptor isoforms through the use of alternative promoters. Gene 290: 35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kast H.R., Nguyen, C.M., Sinal, C.J., Jones, S.A., Laffitte, B.A., Reue, K., Gonzalez, F.J., Willson, T.M., and Edwards, P.A. 2001. Farnesoid X-activated receptor induces apolipoprotein C-II transcription: A molecular mechanism linking plasma triglyceride levels to bile acids. Mol. Endocrinol. 15: 1720-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kast H.R., Goodwin, B., Tarr, P.T., Jones, S.A., Anisfeld, A.M., Stoltz, C.M., Tontonoz, P., Kliewer, S., Willson, T.M., and Edwards, P.A. 2002. Regulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (ABCC2) by the nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor, farnesoid X-activated receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 2908-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten S., Seydoux, J., Peters, J.M., Gonzalez, F.J., Desvergne, B., and Wahli, W. 1999. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J. Clin. Invest. 103: 1489-1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutti D., Kaul, A., and Kralli, A. 2000. A tissue-specific coactivator of steroid receptors, identified in a functional genetic screen. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 2411-2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffitte B.A., Kast, H.R., Nguyen, C.M., Zavacki, A.M., Moore, D.D., and Edwards, P.A. 2000. Identification of the DNA binding specificity and potential target genes for the farnesoid X-activated receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 10638-10647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert G., Amar, M.J., Guo, G., Brewer Jr., H.B., Gonzalez, F.J., and Sinal, C.J. 2003. The farnesoid X-receptor is an essential regulator of cholesterol homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 2563-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman J.J., Barger, P.M., Kovacs, A., Saffitz, J.E., Medeiros, D.M., and Kelly, D.P. 2000. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor g promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 106, 847-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Puigserver, P., Donovan, J., Tarr, P., and Spiegelman, B.M. 2002a. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1β (PGC-1β), a novel PGC-1-related transcription coactivator associated with host cell factor. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 1645-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Wu, H., Tarr, P.T., Zhang, C.Y., Wu, Z., Boss, O., Michael, L.F., Puigserver, P., Isotani, E., Olson, E.N., et al. 2002b. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 α drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature 418: 797-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.T., Makishima, M., Repa, J.J., Schoonjans, K., Kerr, T.A., Auwerx, J., and Mangelsdorf, D.J. 2000. Molecular basis for feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis by nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell 6: 507-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.T., Repa, J.J., and Mangelsdorf, D.J. 2001. Orphan nuclear receptors as eLiXiRs and FiXeRs of sterol metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 37735-37738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makishima M., Okamoto, A.Y., Repa, J.J., Tu, H., Learned, R.M., Luk, A., Hull, M.V., Lustig, K.D., Mangelsdorf, D.J., and Shan, B. 1999. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science 284: 1362-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney P.R., Parks, D.J., Haffner, C.D., Fivush, A.M., Chandra, G., Plunket, K.D., Creech, K.L., Moore, L.B., Wilson, J.G., Lewis, M.C., et al. 2000. Identification of a chemical tool for the orphan nuclear receptor FXR. J. Med. Chem. 43: 2971-2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf D.J. and Evans, R.M. 1995. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell 83: 841-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael L.F., Wu, Z., Cheatham, R.B., Puigserver, P., Adelmant, G., Lehman, J.J., Kelly, D.P., and Spiegelman, B.M. 2001. Restoration of insulin-sensitive glucose transporter (GLUT4) gene expression in muscle cells by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 3820-3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte K., Kranz, H., Kober, I., Thompson, P., Hoefer, M., Haubold, B., Remmel, B., Voss, H., Kaiser, C., Albers, M., et al. 2003. Identification of farnesoid X receptor β as a novel mammalian nuclear receptor sensing lanosterol. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 864-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks D.J., Blanchard, S.G., Bledsoe, R.K., Chandra, G., Consler, T.G., Kliewer, S.A., Stimmel, J.B., Willson, T.M., Zavacki, A.M., Moore, D.D., et al. 1999. Bile acids: Natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science 284: 1365-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P. and Spiegelman, P.M. 2003. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α): Transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocr. Rev. 24: 78-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P., Wu, Z., Park, C.W., Graves, R., Wright, M., and Spiegelman, B.M. 1998. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92: 829-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P., Adelmant, G., Wu, Z., Fan, M., Xu, J., O'Malley, B., and Spiegelman, B.M. 1999. Activation of PPARγ coactivator-1 through transcription factor docking. Science 286: 1368-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puppione D.L. and Charugundla, S. 1994. A microprecipitation technique suitable for measuring α-lipoprotein cholesterol. Lipids 29: 595-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee J., Inoue, Y., Yoon, J.C., Puigserver, P., Fan, M., Gonzalez, F.J., and Spiegelman, B.M. 2003. Regulation of hepatic fasting response by PPARγ coactivator-1α (PGC-1): Requirement for hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α in gluconeogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 4012-4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol W., Choi, H.S., and Moore, D.D. 1995. Isolation of proteins that interact specifically with the retinoid X receptor: Two novel orphan receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 9: 72-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H., Spencer, T.E., Onate, S.A., Jenster, G., Tsai, S.Y., Tsai, M.J., and O'Malley, B.W. 1997. Role of co-activators and co-repressors in the mechanism of steroid/thyroid receptor action. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 52: 141-164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinal C.J., Tohkin, M., Miyata, M., Ward, J.M., Lambert, G., and Gonzalez, F.J. 2000. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell 102: 731-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherepanova I., Puigserver, P., Norris, J.D., Spiegelman, B.M., and McDonnell, D.P. 2000. Modulation of estrogen receptor-α transcriptional activity by the coactivator PGC-1. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 16302-16308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urizar N.L., Dowhan, D.H., and Moore, D.D. 2000. The farnesoid X-activated receptor mediates bile acid activation of phospholipid transfer protein gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 39313-39317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega R.B., Huss, J.M., and Kelly, D.P. 2000. The coactivator PGC-1 cooperates with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α in transcriptional control of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation enzymes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 1868-1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Chen, J., Hollister, K., Sowers, L.C., and Forman, B.M. 1999. Endogenous bile acids are ligands for the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR. Mol. Cell 3: 543-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnick G.R. 1986. Enzymatic methods for quantification of lipoprotein lipids. Methods Enzymol. 129: 101-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Puigserver, P., Andersson, U., Zhang, C., Adelmant, G., Mootha, V., Troy, A., Cinti, S., Lowell, B., Scarpulla, R.C., et al. 1999. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98: 115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J.C., Puigserver, P., Chen, G., Donovan, J., Wu, Z., Rhee, J., Adelmant, G., Stafford, J., Kahn, C.R., Granner, D.K., et al. 2001. Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis through the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Nature 413: 131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Kast-Woelbern, H.R., and Edwards, P.A. 2003. Natural structural variants of the nuclear receptor farnesoid X receptor affect transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]