Abstract

Objective

To examine whether resident communication skills evaluated through patient satisfaction surveys demonstrate evidence of decline through the 3 years of internal medicine residency.

Methods

Data for this study were collected retrospectively from a database of patient satisfaction surveys completed for internal medicine residents at different levels of training. Patient satisfaction was measured with the Aggregated EVGFP (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) questionnaire recommended by the American Board of Internal Medicine.

Results

Over a span of 5 years (2005–2009), a total of 768 patient rating forms were completed for 67 residents during their 3 years of residency training. In postgraduate year (PGY)–1, the residents had a mean satisfaction rating of 4.33 ± 0.48 compared to a mean rating of 4.37 ± 0.45 in their PGY-3 year. Analysis of variance indicated no significant difference by PGY level.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that resident communication skills and patient satisfaction do not decline during the 3 years of residency. This is contrary to our hypothesis that patient satisfaction would worsen as residents progressed through training.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument used in this study (1MB, doc) .

Introduction

Research on physician-patient communication demonstrates an association between physicians' communication skills and patient satisfaction, in addition to quality of care. A systematic review found that effective physician communication ultimately resulted in improved health outcomes.1 Yet, the focus of modern medical education is centered on biomedical mechanisms and less on patients' feelings, concerns, and preferences.2 Recognizing the importance of physician-patient communication, medical educators have instituted changes throughout the medical school curriculum to emphasize patient-centered care.3

Compassionate, appropriate, and effective interpersonal communication is one of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education's core competencies for medical residents.4 We have been evaluating internal medicine residents' communication skills in their continuity clinic through the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) patient satisfaction questionnaire (provided as online supplemental material).5,6 The patient satisfaction questionnaire provides ratings (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor [EVGFP]) biannually by our residents' patients in our ambulatory resident practice. This survey was established in a prior study to provide valuable information about residents' communication skills and their ability to establish effective physician-patient relationships.6

Data from undergraduate medical education literature have demonstrated a transition from patient-centered to physician-centered or paternalistic attitudes over the course of 3 years of medical school (comparing the first year to the third and fourth year of medical school training).3 While this study was based on the medical student perspective, this change in attitude could contribute to worsening communication skills and patient satisfaction as residents progress through training.3 We examined whether our patient satisfaction surveys demonstrated evidence of decline in residents' communication skills during the 3 years of training.

Methods

This study was conducted at the Jefferson Hospital Ambulatory Practice (JHAP) at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. Data were extracted retrospectively from a database of patient satisfaction surveys collected on the internal medicine residents during their rotation at JHAP. The University's Institutional Review Board deemed our study exempt for this use of the patient satisfaction data.

Participants

Annual volume at JHAP is approximately 7600 patient visits. Throughout the year, approximately 90 interns and residents at 3 levels of training in internal medicine are assigned to the clinic, which is organized by day of the week.

Instrument

Patient satisfaction was measured with the Aggregated EVGFP questionnaire recommended by the ABIM (provided as online supplemental material).5,6 This questionnaire was designed to measure personal manner, technical skills, and communication skills by using 10 items and a rating scale of poor, fair, good, very good, and excellent. Internal validity coefficients for this questionnaire form have been reported to range from r = 0.42 to r = 0.72, and reproducibility has been estimated to be 0.70 with 20 patient ratings per resident.6 In the present study the ratings for the 10 items on each questionnaire were averaged to produce a mean satisfaction score for each patient visit.

What was known

Educators are concerned about declining communication skills due to a focus on biomedical problems as residents progress in training and the effect on patient satisfaction.

What is new

Internal medicine residents' communication skills and patient satisfaction do not decline with increasing PGY level.

Limitations

Small sample size and variability in ratings for communication and patient satisfaction.

Bottom line

Communication skills and patient satisfaction at the cohort level appear stable throughout residency.

Procedure

Lay volunteers were recruited during the 5-year period between 2005 and 2009 to administer the questionnaire to patients at the end of their visit to the practice during a 3- to 5-week interval, twice annually. They were trained to explain the purpose of the survey and to offer assistance to the patients in filling out the form, which was voluntary and anonymous.

Analysis

All resident data were deidentified. The ratings for the 3 cohorts were combined. Means were calculated for each resident at each postgraduate year (PGY-1 to PGY-3). The differences across PGY levels were evaluated by using analysis of variance with repeated measures for 67 residents at 3 levels of training with α at .05. The statistical power for this repeated measures analysis to detect a change in mean patient ratings of at least one-half standard deviation for the sample of 67 residents was determined to be 0.80 at an alpha of .05 and assuming a correlation of 0.50 between ratings at different points in time.

Results

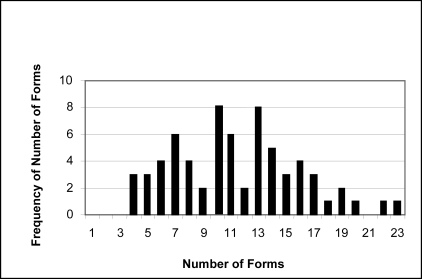

Over a span of 5 years (2005–2009), a total of 768 patient rating forms were completed for 67 residents during their 3 years of residency training. On average, there were 11 rating forms for each resident (mean ± SD, 11.5 ± 4.5). Most (90%, 691 of 768) had at least 6 forms, with up to 23 forms for 1 resident (figure).

Frequency Distribution of 768 Patient Satisfaction forms among the 67 Residents

The overall visit satisfaction rating was determined by level of residents on a scale of 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). PGY-1 residents had a mean satisfaction rating of 4.33 ± 0.48 as compared to PGY-2 residents with a mean of 4.37 ± 0.44 and PGY-3 residents with a mean satisfaction rating of 4.37 ± 0.45. Analysis of variance indicated no significant difference by PGY level. However, a difference of mean satisfaction was noted to be significant among individual residents (P < .02) but this did not change with PGY level.

Discussion

We sought to determine progression of patient satisfaction in a single academic center clinic as residents advanced from PGY-1 to PGY-3. By using the Aggregated EVGFP questionnaire, we were able to log surveys from 67 residents who had available data over the course of 5 years (2005–2009). Our data show that patient satisfaction remains the same as residents advance in their training. This is contrary to our hypothesis that patient satisfaction would worsen as residents progressed through residency training. Our initial approach was based on medical school literature supporting a more paternalistic, physician-centered approach to patient care as students progress through their training.3 With this trend and increasing training fatigue, we postulated worsening communication skills and a resultant decline in patient satisfaction. This, however, was not demonstrated, as we observed no deterioration in scores. Possible reasons for this trend include clinic reputation, efficiency, a more longstanding relationship with patients, and loss to follow-up for dissatisfied patients due to dropout, as demonstrated in prior studies.7 Additionally, with this study focused on longitudinal clinic evaluations, we postulate that the extended relationship between physician and patient would lead to a more positive evaluation, particularly for those who chose internal medicine careers. Finally, clinic dropout rates 5 positively affect scoring, as patients have either left the clinic or found a different physician.

We also found that the overall patient satisfaction scores from both groups were in the very good to excellent range (4.33 ± 0.48, 4.37 ± 0.45). In previous research, it has been recognized that evaluation by patients is positively biased.6 This is in part reflected in the “halo” effect, as patients have a more favorable opinion of the individual resident, whereas overall satisfaction of their outpatient interaction is lacking. This is also evident with patient satisfaction in the quality and reputation of the clinic tending to produce skewed scores.7 By using the patient satisfaction questionnaire, we must be aware of this bias and not be overconfident in our residents' performance. These high scores, while reassuring, make it challenging to detect small improvements or a decline in communication skills as residents advance through their training.

There are several limitations to our study. Our small sample size (n = 67) had a wide variation in individual scores. Because the survey instrument was administered during a 3- to 5-week interval, twice annually, some residents did not have data collected, and our ability to draw on data for residents who had surveys during all 3 years was limited. Our plan to use an independent surveyor trained specifically for the purpose of approaching patients at the time of checkout from the clinic avoided an interference with the physician-patient relationship, but it also decreased the number of trainees for whom complete data were available. Although this sample is not sufficient for making inferences about the performance of individual residents at different levels of training, it does provide meaningful information about groups of residents at each level of training. The “halo” effect might also skew the data. Despite these limitations, we believe these data demonstrate that resident communication skills and patient satisfaction do not decline during the 3 years of internal medicine residency.

Footnotes

All authors are at Jefferson Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University. Emily A. Stewart, MD, is Chief Medical Resident, Department of Medicine; Dina Halegoua-De Marzio, MD, is Chief Medical Resident, Department of Medicine; Douglas E. Guggenheim, MD, is Chief Medical Resident, Department of Medicine; Joanne Gotto, MEd, is Business Manager, Department of Medicine; J. Jon Veloski, MS, is Director of Medical Education Research, Center for Research in Medical Education and Health Care; and Gregory C. Kane, MD, is Interim Chair, Department of Medicine.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152(9):1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine's hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403–407. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haidet P, Dains JE, Paterniti DA, et al. Medical student attitudes toward the doctor-patient relationship. Med Educ. 2002;36:568–574. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hechtel L, Chang T, Tseng E, et al. ACGME Outcome Project. Common Program Requirements: general competencies. http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compCPRL.asp. Approved 2 13, 2007. Accessed 2 22, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLeod PJ, Tamblyn R, Benoroya S, Snell L. Faculty ratings of resident humanism predict patient satisfaction ratings in ambulatory medical clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:146–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02599179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamblyn R, Benaroya S, Snell l, McLeod P, Schnarch B, Abrahamowicz M. The feasibility and value of using patient satisfaction ratings to evaluate internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:146–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02600030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehmann F, Fontaine D, Bourque A, Côté L. Measurement of patient satisfaction: the Smith-Falvo patient-doctor interaction scale. Can Fam Physician. 1988;34:2641–2645. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]