Abstract

Background

Professional organizations have called for individualized training approaches, as well as for opportunities for resident scholarship, to ensure that internal medicine residents have sufficient knowledge and experience to make informed career choices.

Context and Purpose

To address these training issues within the University of California, San Francisco, internal medicine program, we created the Areas of Distinction (AoD) program to supplement regular clinical duties with specialized curricula designed to engage residents in clinical research, global health, health equities, medical education, molecular medicine, or physician leadership. We describe our AoD program and present this initiative's evaluation data.

Methods and Program Evaluation

We evaluated features of our AoD program, including program enrollment, resident satisfaction, recruitment surveys, quantity of scholarly products, and the results of our resident's certifying examination scores. Finally, we described the costs of implementing and maintaining the AoDs.

Results

AoD enrollment increased from 81% to 98% during the past 5 years. Both quantitative and qualitative data demonstrated a positive effect on recruitment and improved resident satisfaction with the program, and the number and breadth of scholarly presentations have increased without an adverse effect on our board certification pass rate.

Conclusions

The AoD system led to favorable outcomes in the domains of resident recruitment, satisfaction, scholarship, and board performance. Our intervention showed that residents can successfully obtain clinical training while engaging in specialized education beyond the bounds of core medicine training. Nurturing these interests 5 empower residents to better shape their careers by providing earlier insight into internist roles that transcend classic internal medicine training.

Introduction

Creating outstanding clinicians is the primary goal of internal medicine training.1,2 However, many residents also want to explore potential career pathways as clinician investigators, leaders, or educators. Professional organizations, including the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM), and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) through its Educational Innovation Project (EIP) have called for individualized training approaches to ensure that residents have sufficient knowledge to make informed career choices.3 The 2010 Carnegie study on medical education4 recommended creating individualized learning pathways within medical training, providing learners opportunities to experience broader professional roles, and creating smaller learning communities within larger programs to promote career development.

Internal medicine programs are expected to counsel learners about careers and to provide opportunities for scholarship as defined by discovery, integration, application, or teaching.5 Traditionally, programs have relied on core educational faculty to mentor residents and facilitate career development. Mentoring and career development are interlinked with a positive association between quality mentoring and successful career development.6,7 However, by depending on traditional program mentors, residents 5 lack opportunities to experience the variety of potential internal medicine careers. In addition to providing general counseling and career advice, faculty mentors often direct residents formulating scholarly projects. Although scholarship is expected of internal medicine residents,5 with the exception of institutions that have focused research tracks, programs often lack an optimal infrastructure and ready access to qualified faculty who can support resident scholarship.8,9 Therefore, curricula that are more explicit are needed to facilitate development of both career awareness and scholarship.

To address these issues of mentorship, career development, and resident scholarship, we created our Areas of Distinction (AoD) program. This program, targeted at residents in their last 2 years of training, engages residents in education beyond the bounds of core internal medicine education. The AoD program provides individualized mentorship and smaller learning communities while simultaneously promoting resident scholarship. We provide a framework for institutions interested in developing similar initiatives for their residency programs by describing the AoDs and our evaluation of this initiative.

What was known

Individualized training approaches are thought to help residents make more informed career choices.

What is new

An internal medicine program created a program to introduce residents to specialized curricula in clinical reserach, global health, health equalities, medical education, and leadership.

Limitations

Lack of a formal comparison group, and breadth of faculty expertise needed 5 not exist in smaller departments.

Bottom line

Emphasis on academic domains in core residency can have a positive effect on resident recruitment, scholarship, and board performance.

AoD Program Description

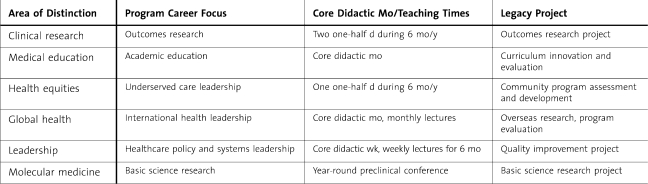

In 2007, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), Internal Medicine Residency Program implemented 6 AoDs: (1) clinical research, (2) global health, (3) health equities, (4) medical education, (5) molecular medicine, and (6) physician leadership and health systems. Each AoD features a community of learners and faculty with similar interests, didactic content, and experiential activities. Introductory core content is provided to first-year participants; the remaining didactic material is sequenced over a 2-year period. Residents either individually or jointly produce a scholarly project. Often, second-year participants guide or directly teach first-year participants. Although each AoD is led by 1 or 2 dedicated faculty members, all AoDs draw on an interdepartmental faculty community. Residents complete the curriculum during their 12 months of ambulatory education in their second and third years of residency. table 1 summarizes selected curricular features for each AoD. Materials from individual AoDs are available upon request. In 2009, UCSF initiated the Pathways to Discovery program across all residencies, the undergraduate medical school, and other schools within UCSF. Many of our AoDs have now merged their programs with the pathways program.

TABLE 1.

Curricular Features of Each Area of Distinction

Individual AoD Descriptions

Clinical Research

The longest standing AoD is the clinical research program (formerly called the primary medical education [PRIME] program),9 which focuses on exposing residents to epidemiology and clinical outcomes research. The clinical research curriculum features a month-long, core, research methods course followed by weekly epidemiology-based didactics, resident work-in-progress sessions, and journal clubs to ensure familiarity with the medical literature. Resident scholarly projects in this AoD include secondary data analyses, chart reviews of clinical outcomes, and systematic reviews of clinical topics.

Global Health

The global health AoD cultivates future leaders in international health by developing cross-cultural competence in resource-limited settings. The curriculum covers topics such as health development, human rights, communicable diseases, vulnerable populations, and leadership skills. Residents take a 1-month, introductory core course; bimonthly, evening work-in-progress sessions; and bimonthly, core, didactic sessions. Third-year residents participate in a 1-month international elective, conducting field work. This is paid for through an endowment fund created for this purpose. Examples of scholarly projects include international outcomes research and disease prevention interventions. Recent integration of this AoD with the campus-wide Pathways to Discovery program enhances its interdisciplinary nature.

Health Equities

The health equities AoD prepares leaders in caring for underserved populations. A social medicine curriculum, delivered as either weekly didactics or targeted site visits during ambulatory months, explores ways in which societal factors influence health and health care. Residents also attend clinics that provide care to underserved patients (eg, homeless outreach, prison hospitals, and drug treatment programs). Examples of scholarly projects include research and evaluations of public health programs for underserved patients. The health equities track is now 1 of 2 graduate medical education tracks within the campus's Health and Society Pathway; we currently arrange a shared core curricular week with the other track (leadership and health systems), in addition to its own weekly sessions.

Medical Education

The medical education AoD is for residents interested in becoming educators, curriculum developers, educational researchers, and medical education leaders. The curriculum is delivered in weekly half-day sessions over 2 years and is focused on teaching strategies and curricular development. Residents also participate in experiential activities, such as teaching medical students in small-group sessions, becoming a preceptor for students in clinic, or working in the assessment of medical students in clinical-observation exercises. Examples of scholarly projects include creation of curricular aids and evaluation of curricular innovations. This AoD joined the current Pathway in Health Professions Education and redistributed didactics into a month-long course covering teaching strategies and curriculum development as well as 3 flexibly scheduled courses in learning theory, assessment, and educational leadership.

Molecular Medicine

The molecular medicine AoD provides advanced education in the experimental study of the molecular and cellular basis of disease to residents committed to a career in biomedical research. The curriculum is delivered through monthly seminars and journal clubs attended by residents and physician-scientist faculty members. In contrast to the other AoDs, residents join this AoD at the time of program matriculation. Participants enter a fellowship after postgraduate year-2 (PGY-2) through the American Board of Internal Medicine Research Pathway. Scholarly projects are developed to coordinate with their fellowship plans. Activities of this AoD have been integrated with the Molecular Medicine Pathway, so residents now share these activities with students and fellows training as physician-scientists.

Leadership and Health Systems

The leadership and health systems AoD offers curriculum in leadership, health system change, and health care policy. Participants prepare for roles leading physician groups, patient safety/quality initiatives, or health policy development. Residents take a 1-week, core introductory course, followed by weekly, 1-hour, didactic sessions. Scholarly projects are selected and completed as a group activity. Individuals additionally 5 complete their own projects. Examples of group-mentored activities include hospital system quality-improvement projects and systems redesigns. The leadership and health systems track is now 1 of 2 tracks within the Health and Society Pathway and includes students, residents, and fellows from across campus.

Implementation

The specific AoDs were created based on UCSF faculty member expertise, as well as on unmet curricular needs as ascertained by resident feedback. The residency program director recruited appropriate faculty to lead each AoD. With the exception of molecular medicine, PGY-1 residents select an AoD during the winter of their internship year.

To facilitate AoD resident participation, we increased the time spent in ambulatory medicine in the PGY-2 and PGY-3 to 12 months total. Residents rotated between inpatient and ambulatory settings in 2-month blocks. For 6 months each year, AoD residents performed inpatient duties typical of an internal medicine resident. For the other 6 months, they were assigned duties in the ambulatory setting, and during that time, could participate in an AoD. Resident participation in an AoD is voluntary, and before the selection, we sponsored formal information nights and encouraged first-year residents to meet with individual AoD leaders so they could make informed decisions. Residents 5 choose only one AoD, and those who choose not to participate in the AoDs are able to remain in their categorical or primary care tracks, which continue in parallel and provide ongoing didactics and mentorship.

Program Evaluation

We used 6 metrics to evaluate our AoD program: (1) enrollment; (2) satisfaction, measured by both survey and qualitative data; (3) effect of the AoDs on recruitment, measured through surveying incoming residents; (4) effect of the AoDs on the quantity of scholarly products generated during residency training; (5) effect on learning, measured through successful Board certification; and (6) AoD costs.

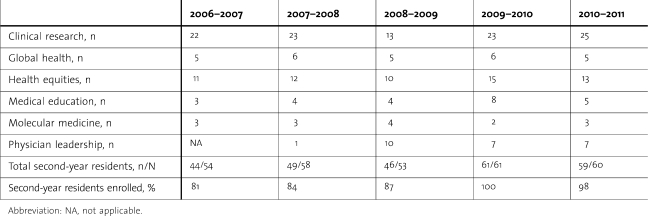

Enrollment in the AoDs

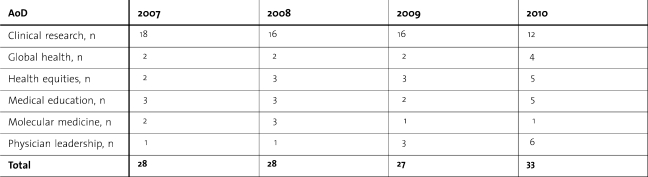

By 2007, all 6 AoDs were fully active. The trends in increasing enrollment are shown in table 2; we show second-year resident data only because virtually all residents entering a specific AoD completed their final 2 training years within that AoD.

TABLE 2.

Areas of Distinction Enrollment by Year

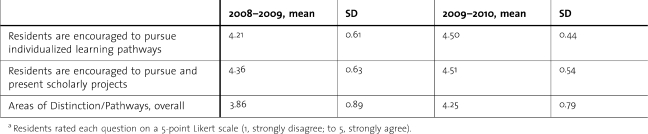

Resident Satisfaction

In 2008–2009, we initiated a graduation resident survey with 3 of 20 items (15%) specifically addressing the AoDs. Residents rated each question on a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; to 5, strongly agree). Graduating residents responded positively to all 3 questions regarding the AoDs (table 3). Their answers have shown a steady improvement from 2008 to 2010.

TABLE 3.

Results of Area of Distinction–Specific Items on Residency Program Surveya

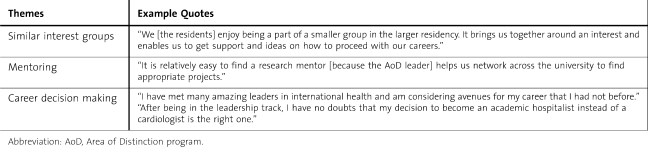

We also conducted 3 focus groups in 2009, with 36 residents participating. Focus groups were recorded, transcribed, reviewed, and coded by 2 of the authors (J.K. and R.S.). Codes and themes were generated by consensus. We identified 3 themes: residents (1) enjoyed being grouped with residents of similar interests, (2) felt the AoD program improved access to mentoring, and (3) felt that participation in AoD activities helped with career decision making. table 4 provides sample comments to support these themes.

TABLE 4.

Themes From the Qualitative Analysis of Focus Group Discussion

Intern Recruitment

In 2008, we added AoD-specific questions to our annual incoming intern survey. Of 120 residents accepted over 2 years, 112 (93%) responded to the survey, and all confirmed their familiarity with the AoD program. On this survey, PGY-1 residents could indicate interest in any of the 6 AoDs. All respondents indicated an interest in at least one AoD, with 32.1% (n = 36) selecting 1 AoD, 43.8% (n = 49) 2 AoDs, 22.3% (n = 25) 3 AoDs, and 1.8% (n = 2) 4 AoDs. The clinical research and the medical education AoDs were the AoDs most commonly mentioned by incoming interns. On a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), the incoming residents rated the influence of the AoD program on their selection of UCSF for residency training. This score increased from 2.83 (SD = 0.52) in 2008 to 3.77 (SD = 0.09) in 2009 and 3.86 (SD = 0.25) in 2010.

Medical Knowledge

We assessed if time spent in AoD activities might translate into less mastery of core internal medicine knowledge. Our residents' first-time pass rate on the internal medicine certifying examination since full implementation of the AoD program is 99% (159/161 residents) which is identical to that measure in the 3 years that preceded the AoDs (157/159 residents).

Academic Legacy Projects

We measured scholarly output by recording the number and type of presentations done at the end of each academic year at our annual Resident Research Symposium (table 5). The scholarly output of each AoD mirrors the enrollment of residents in the AoDs. As more residents have chosen other AoDs, the clinical research AoD had fewer presentations, but the output of the other AoDs has increased over this period.

TABLE 5.

Resident Research Symposia Participation by Area of Distinction (AoD)

Costs of Program Implementation

The AoD program costs include resident, faculty, and administrator salaries, as well as expenditures for supplies and other miscellaneous items. Resident salaries are distributed to the assigned ambulatory or elective rotation and have resulted in no additional costs. In 2007–2008, faculty salary support was not provided. The need for significant time commitment became apparent, and salary support was added in 2008–2009. Each AoD faculty director receives 5% to 10% salary support to manage the program. Each AoD also receives 20% to 40% time support of an administrator to help support program issues.

Discussion

The UCSF AoD program allows residents to participate in 6 distinct specialized experiences during their latter 2 years of training. We have demonstrated that it is feasible to implement these educational opportunities with favorable outcomes in the domains of resident satisfaction, recruitment, board performance, and scholarship. We believe this success relates to the AoD program providing relevant and compelling educational experiences, tailoring mentoring, and creating smaller educational communities. Residents and fellows from all specialties can participate in such a program because of the transformation from a single residency program to a campus-wide program.

We demonstrate that AoD participation helps residents decide on potential career pathways. Many residents recognize a wide variety of career options in broader professional roles. Social cognitive career theory describes a learner's perception of increased self-efficacy with career-related tasks when they experience success in new endeavors. These experiences greatly influence future career choices among developing professionals.10 Our curriculum design enables residents to make their initial postresidency career choices after having experienced a broad range of options.

To successfully implement the AoD program, we needed to create more ambulatory time in the latter 2 years of residency and restructure resident schedules into 2-month blocks. Planning for AoD educational activities involved creation of introductory core material for new participants and a 2-year curriculum appropriate for each learner level. Faculty members were recruited by each AoD leader to provide curricular content; these faculty members also served as advisors and mentors. With the incorporation of most AoDs into the UCSF Pathways program, learners from many disciplines are able to participate together, which enables our AoD faculty to assume campus-wide leadership roles.

Another challenge was recruiting expert faculty and providing them with time and resources to plan and deliver the curriculum as well as to mentor residents. Key AoD faculty members are now financially supported and receive academic recognition for their administrative, educational, and mentoring work.

Our descriptive study has several important limitations. First, it is an educational innovation at a single, large academic institution with a depth and breadth of faculty expertise that supported such an ambitious undertaking. However, we believe that this program could be adapted, in full or in part, by many institutions that have motivated faculty with similar curricular expertise. Second, we were unable to include a comparison group to examine differences in satisfaction, career path, and scholarly productivity because most residents participated in the program. Finally, we do not have longitudinal data regarding the ultimate effect of the AoD program on resident career choices.

Our innovative AoD program has contributed to a transformative change in medical education at our institution by serving as a nidus for the UCSF Pathways to Discovery program, which offers specialized, longitudinal training experiences for medical students, residents, and fellows as well as for learners from the other health care professional schools at UCSF.11 As the AoD program has merged with Pathways, our residents have new opportunities to work and learn collaboratively across different specialties and professions. Importantly, our program enables us to address the call for individualized learning tracks.4 More broadly, our experience demonstrates that academic institutions can continue to ensure that residents obtain outstanding clinical training while simultaneously creating opportunities for residents to experience expanded careers during their traditional residency education.

Footnotes

All authors are at University of California-San Francisco. R. Jeffrey Kohlwes, MD, MPH, is Associate Program Director Internal Medicine Residency Program and Director of the PRIME Residency Program, Veteran‘s Affairs Medical Center; Patricia Cornett, MD, is Associate Chair for Education in the Department of Internal Medicine, Veteran‘s Affairs Medical Center; Madhavi Dandu, MD, is Director of the International Health Area of Distinction; Katherine Julian, MD, is Director of the Primary Care Residency Program; Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, is Past Director of the Quality and Leadership Area of Distinction; Tracy Minichiello, MD, Past Director of the International Health Area of Distinction, Veteran‘s Affairs Medical Center; Rebecca Shunk, MD, is Associate Director of the PRIME Program, Veteran‘s Affairs Medical Center; Sharad Jain, MD, is Director of Primary Care Internal Medicine Residency, San Francisco General Hospital; Elizabeth Harleman, MD, is Associate Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program; Sumant Ranji, MD, is Associate Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program; Brad Sharpe, MD, is Associate Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program; Patricia O'Sullivan, PhD, is Director of Research and Development in Medical Education in the Office of Medical Education; and Harry Hollander, MD, is Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.American Board of Internal Medicine. About ABIM: Certification by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) http://www.abim.org/about/. Accessed 9 23, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Educational Innovation Project. http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/RRC_140/140_EIPindex.asp. Accessed 9 23, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgibbons JP, Bordley DR, Berkowitz LR, Miller BW, Henderson MC Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine. Redesigning residency education in internal medicine: a position paper from the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):920–926. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irby DM, Cooke M, O'Brien BC. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):220–227. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements: effective: 7 1, 2011. http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/home/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011.pdf. Accessed 12 10, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marušić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marušić A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72–78. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bierer SB, Chen HC. How to measure success: the impact of scholarly concentrations on students—a literature review. Acad Med. 2010;85(3):438–452. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181cccbd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohlwes RJ, Shunk RL, Avins A, Garber J, Bent S, Shlipak MG. The PRIME curriculum: clinical research training during residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):506–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakken LL, Byars-Winston A, Wang MF. Viewing clinical research career development through the lens of social cognitive career theory. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2006;11(1):91–110. doi: 10.1007/s10459-005-3138-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. Pathways to Discovery (PTD): training UCSF learners to contribute to health and health care beyond the excellent care of individual patients. http://medschool.ucsf.edu/pathways/. Accessed 9 23, 2011. [Google Scholar]