Abstract

Background

Quality improvement (QI) education in residency training is important and necessary for accreditation. Although the literature on this topic has been growing, some specialties, in particular psychiatry, have been underrepresented.

Methods

We developed a didactic and experiential QI curriculum within a US psychiatry residency program that included a seminar series and development of QI projects. Evaluation included resident knowledge using the Quality Improvement Knowledge Application Tool, implementation of resident QI projects, and qualitative and quantitative satisfaction with the curriculum.

Results

Our curriculum significantly improved QI knowledge in 2 cohorts of residents (N = 16) as measured by the Quality Improvement Knowledge Application Tool. All resident QI projects (100%) in the first cohort were implemented. Residents and faculty reported satisfaction with the curriculum.

Conclusions

Our curriculum incorporated QI education through didactic and experiential learning in a moderately sized US psychiatry residency program. Important factors included a longitudinal experience with protected time for residents to develop QI projects and a process for developing faculty competence in QI. Further studies should use a control group of residents and examine interprofessional QI curricula.

Background

Educating residents about quality improvement (QI) is important for many reasons. QI spans 2 of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) 6 competencies—practice-based learning and improvement and systems-based practice. The ACGME requirements state that residents must be “integrated and actively participate in interdisciplinary clinical quality improvement and patient safety programs.”1 Performing QI activities will soon be linked to maintenance of certification, maintenance of licensure, and even reimbursement by Medicare.2

Reports of QI education within residency training are increasingly common, with primary care representing most of this work.3 A 2009 review found 28 reports documenting residency QI curricula, 9 of which described QI didactic instruction, followed by engagement in QI activities.4 Curricula that combine didactic and experiential learning appear most effective.5,6 Most QI curricula are time-limited, often consisting of only a 4-week rotation, which 5 explain the finding that few resident QI projects are implemented.4 Another barrier is the shortage of faculty educated in QI.7 Moreover, some specialties, including psychiatry, lag behind others in development of performance measures.8

A more-recent review showed that most published studies on QI curricula had small sample sizes and low response rates.3 Acquisition of QI knowledge has typically been evaluated via subjective self-assessments as opposed to established assessment tools.3,9 However, some reports use the Quality Improvement Knowledge Application Tool (QIKAT), which assesses ability to apply core concepts of improvement to cases.6,10,11

Our review of the literature found only one published psychiatry QI curriculum, from a Canadian residency program.12 Third-year (postgraduate year-3 [PGY-3]) residents participated in QI didactics and projects; outcomes consisted of focus groups to examine attitudes toward QI training following the curriculum. To address the paucity of psychiatry QI education in the literature, we developed and assessed a didactic and experiential QI curriculum for US psychiatry residents. We describe our curriculum, outcomes, and recommendations for future directions.

Methods

Curricular Development

To develop our curriculum, we used literature review, internal-medicine residency leaders at our university who had already developed an innovative QI curriculum,13 and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement website.14,15

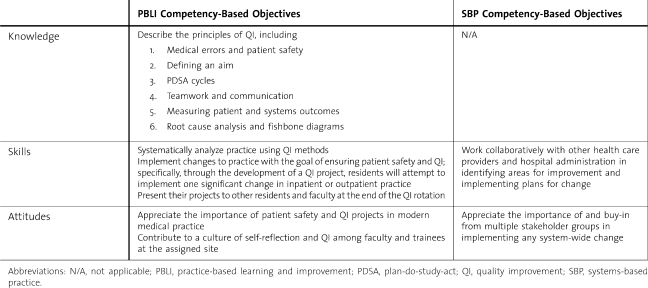

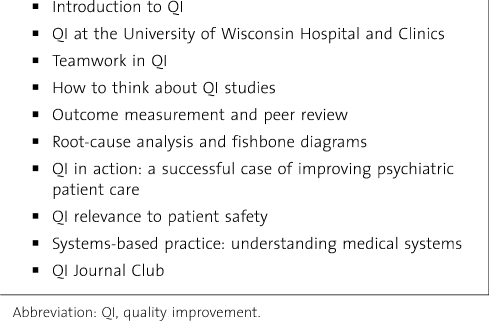

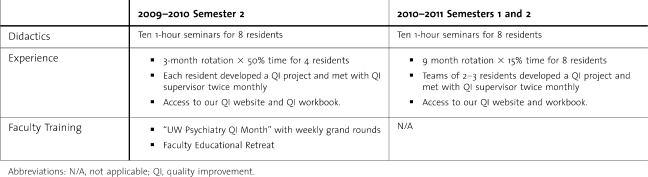

Our educational objectives were focused on the practice-based learning and improvement and systems-based practice competencies (table 1). Our didactics consisted of 10 seminars, 1-hour each (table 2). For resident cohort 1, the QI rotation was 3 months long with 50% protected time (table 3). Each resident was assigned to a psychiatry unit, where he or she developed a QI project, had a QI project supervisor, and was given an internally developed QI workbook. At the end of the rotation, residents presented their projects at departmental conferences.

TABLE 1.

Competency-Based Objectives for Psychiatry Quality Improvement Rotation

TABLE 2.

Seminar Topics for Psychiatry Quality Improvement Didactics

TABLE 3.

Psychiatry Quality Improvement Curriculum for Cohort 1 Versus Cohort 2

After cohort 1 completed the curriculum, we reviewed the assessments and met with project supervisors. This led to a change in the rotation to 9 months at 15% protected time. Consistent with literature reports, residents and supervisors felt that a longer experience would be helpful in implementing projects. Additionally, we changed the format so that QI projects would be completed in teams of 2 to 3 residents. The University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board determined the educational study to be exempt from review, and the QI activities did not require formal Institutional Review Board review.

Faculty Development

To address faculty development in QI, we created a department-wide “QI Month” during which we held weekly grand rounds on QI topics. The month concluded with a 1-day Educational Retreat entitled “Quality Improvement: What's in it for Me? consisting of interactive breakout sessions for faculty to learn QI basics.

Evaluation

Assessment of our QI didactic curriculum included predidactic and postdidactic administration of the QIKAT, which was given to PGY-3 residents during their seminar time. The QIKAT contains 2 scenarios, with each scored from 0 (low) to 5 (high), with the highest score being 10. The scenarios were written specifically for psychiatry residents. Responses were blinded and scored by 2 raters using the standard QIKAT scoring rubric.10 Discrepancies were reconciled between the scorers. Pretest and posttest scores for each resident cohort were compared using paired t tests. We tabulated separate scores for each cohort because of the change in curriculum that occurred. We assessed attitudes toward QI learning through qualitative evaluations of the seminars via free-text responses to standard questions and quantitative evaluations of the experiential rotation via Likert scales. Finally, we qualitatively assessed resident QI projects for content and implementation.

Results

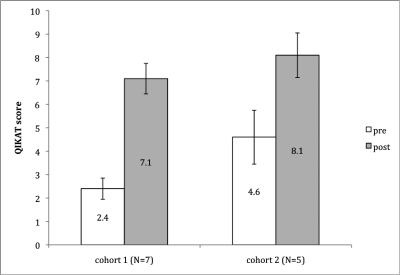

In cohort 1, 7 of 8 residents completed both predidactic and postdidactic QIKAT assessments. The QIKAT scores improved from a mean of 2.4 (SD 0.9) to 7.1 (SD 1.3) (P < .001). In cohort 2, 5 of 8 residents completed both pre-QIKAT and post-QIKAT assessments. One resident in cohort 1, and 3 in cohort 2, did not complete the posttest because they were on leave or vacation. Scores again improved, this time from a mean of 4.6 (SD 2.3) to 8.1 (SD 1.9) (P < .05; figure).

FIGURE.

Residents' Knowledge of QI Principles Pre-QI and Post-QI Didactics, as Measured by Mean QIKAT Scores (10 = Best)

Abbreviations: QI, quality improvement; QIKAT, Quality Improvement Knowledge Application Tool.

Resident evaluations of the QI seminars were positive. Comments included “inspiring” and “very useful for the QI rotation.” Resident evaluations of the QI experiential rotation have also been positive, showing a mean score of 5 out of 5 (5 best) for “overall satisfaction with rotation,” and 4.3 out of 5 for “impact on learning.”

Four resident QI projects thus far have been completed. The first was the development of a psychiatry intern how-to manual to standardize the process for learning inpatient procedures. The second was designed to increase resident/faculty attendance at department-wide seminars via the development of online streaming of these seminars to remote sites. Attendance improved 25% over 3 months. The third was development of a process to minimize the time psychiatric patients spend in the emergency department, the result of which was that waiting time from consultation to disposition decreased from 3.5 to 2.05 hours over 3 months. Finally, a resident developed a system ensuring that all psychiatry consults placed in our hospital are systematically transmitted to the psychiatry team.

Discussion

In developing our curriculum, we addressed problems that have been described as commonplace in QI curricula. As the second report of a psychiatry residency QI curriculum, we built on the first by incorporating quantitative assessment of our curriculum and by examining the feasibility of a longitudinal QI curriculum within a more modestly sized program. It is difficult to know precisely which ingredients were necessary for the success of our curriculum. However, many reports have highlighted the need for greater faculty development to achieve sufficient numbers of teachers of QI.3 Our QI Month and QI Retreat addressed this for our department. Likewise, we met frequently with interprofessional stakeholders who would be involved in implementing QI projects and chose QI project mentors who were able to facilitate system change.

Factors that contributed to the success of the projects included providing relatively long durations for the rotation, requiring residents to present projects at department-wide conferences, informing residents of other opportunities for scholarly presentations of their work, and providing protected time. Additionally, one resident enrolled in a QI elective and another on the department QI committee was more engaged because of her training in the core QI curriculum.

Our study limitations include small sample size and a single-site intervention. We relied on 7 faculty members knowledgeable in QI, 3 of whom each contributed 18 hours per academic year and 4 of whom contributed less than 2 hours each. This amount of time and expertise might be unavailable in some settings, limiting generalizability. We did not include a control group and thus cannot rule out the possibility that changes occurred because of other trends in training, although this seems unlikely. We did not track the direct costs, but, apart from faculty time, these were minimal.

Future QI curriculum initiatives could involve system-wide QI curricula, cutting across multiple education programs at a given hospital. If programs are teaching systems-based practice via QI curricula, then it makes sense to teach across specialties and professions with nursing, social work, and administration. 5o Clinic has instituted a QI curriculum across specialties, but the effects on learner knowledge, skills, and attitudes are not yet known.16

Conclusions

We have provided evidence that a didactic and experiential QI curriculum within a US psychiatry residency program can increase QI knowledge and lead to implemented QI projects. Important factors might include faculty development and a longitudinal curriculum with protected resident time. Further studies should examine curricula that use a control group and cross-specialty QI curricula.

Footnotes

Claudia L. Reardon, MD, is Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Associate Residency Training Director, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health; Greg Ogrinc, MD, MS, is Associate Professor of Community and Family Medicine and Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School and Senior Scholar at White River Junction Veterans Administration Quality Scholars Program; and Art Walaszek, MD, is Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Residency Training Director, and Vice Chair for Education at University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Funding: This material is based on support, resources, and the use of facilities at the White River Junction Veterans Administration in White River Junction, VT.

The authors are indebted to Dean Krahn, MD, MS, and Eric Heiligenstein, MD, for their help designing and implementing the curriculum.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME 2010 common program requirements. http://acgme-2010standards.org/pdf/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011.pdf, Accessed 12 6, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oldham JM, Golden WE, Rosof BM. Quality improvement in psychiatry: why measures matter. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008;14((suppl 2)):8–17. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000320122.53681.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong BM, Etchells EE, Kuper A, Levinson W, Shojania KG. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1425–1439. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e2d0c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patow CA, Karpovich K, Riesenberg LA, Jaeger J, Rosenfeld JC, Wittenbreer M, et al. Residents' engagement in quality improvement: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1757–1764. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bf53ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman MT, Nasraty S, Ostapchuk M, Wheeler S, Looney S, Rhodes S. Introducing practice-based learning and improvement ACGME core competencies into a family medicine residency curriculum. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29:238–247. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogrinc G, Headrick LA, Morrison LJ, Foster T. Teaching and assessing resident competence in practice-based learning and improvement. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19((5, pt 2)):496–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosser G, Frisch KK, Skarda PK, Gertner E. Addressing the challenges in teaching quality improvement. Am J Med. 2009;122(5):487–491. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel KK, Butler B, Wells KB. What is necessary to transform the quality of mental health care. Health Aff. 2006;25(3):681–693. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boonyasai RT, Windish DM, Chakraborti C, Feldman LS, Rubin HR, Bass EB. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298(9):1023–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison LJ, Headrick LA, Ogrinc G, Foster T. The quality improvement knowledge application tool (QIKAT): an instrument to assess knowledge application in practice-based learning and improvement [abstract] J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18((suppl)):250. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varkey P, Karlapudi SP. Lessons learned from a 5-year experience with a 4-week experiential quality improvement curriculum in a preventive medicine fellowship. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(1):93–99. doi: 10.4300/01.01.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sockalingam S, Stergiopoulos V, Maggi J, Zaretsky A. Quality education: a pilot quality improvement curriculum for psychiatry residents. Med Teach. 2010;32(5):e221–e226. doi: 10.3109/01421591003690346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland R, Meyers D, Hildebrand C, Bridges AJ, Roach MA, Vogelman B. Creating champions for health care quality and safety. Am J of Med Qual. 2010;25(2):102–108. doi: 10.1177/1062860609352108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batalden P, Berwick D, Bisognano M, Splaine M, Baker G, Headrick L. Knowledge Domains for Health Care Professional Students Seeking Competency in the Continual Improvement and Innovation of Health Care. Boston, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogrinc G, Headrick LA, Mutha S, Coleman MT, O'Donnell J, Miles PV. A framework for teaching medical students and residents about practice-based learning and improvement, synthesized from a literature review. Acad Med. 2003;78(7):748–756. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200307000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varkey P, Karlapudi S, Rose S, Nelson R, Warner M. A systems approach for implementing practice-based learning and improvement and systems-based practice in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2009;84:335–339. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819731fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]