Abstract

Background

An effective working relationship between chief residents and residency program directors is critical to a residency program's success. Despite the importance of this relationship, few studies have explored the characteristics of an effective program director-chief resident partnership or how to facilitate collaboration between the 2 roles, which collectively are important to program quality and resident satisfaction. We describe the development and impact of a novel workshop that paired program directors with their incoming chief residents to facilitate improved partnerships.

Methods

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education sponsored a full-day workshop for residency program directors and their incoming chief residents. Sessions focused on increased understanding of personality styles, using experiential learning, and open communication between chief residents and program directors, related to feedback and expectations of each other. Participants completed an anonymous survey immediately after the workshop and again 8 months later to assess its long-term impact.

Results

Participants found the workshop to be a valuable experience, with comments revealing common themes. Program directors and chief residents expect each other to act as a role model for the residents, be approachable and available, and to be transparent and fair in their decision-making processes; both groups wanted feedback on performance and clear expectations from each other for roles and responsibilities; and both groups identified the need to be innovative and supportive of changes in the program. Respondents to the follow-up survey reported that workshop participation improved their relationships with their co-chiefs and program directors.

Conclusion

Participation in this experiential workshop improved the working relationships between chief residents and program directors. The themes that were identified can be used to foster communication between incoming chief residents and residency directors and to develop a curriculum for chief resident development.

Background

The partnership between chief resident and residency program director is integral to a residency program's success. The chief resident is viewed by most program directors as a critical liaison between the residents and faculty.1,2 In addition to being a role model, teacher, administrator, and clinician, the chief resident needs to advocate for the residents, foster teamwork within the residency program, and be able to take a broader view of problems that arise in complex and rapidly changing academic health care systems. In a study by Norris et al,3 family medicine program directors placed significant importance on the administrative role of chief residents. Conversely, chief residents reported a lack of preparation for dealing with administrative tasks and personnel issues and a lack of a clear job description. This 5 have led to a perception of burnout in these chief residents. In response to a survey, physical medicine and rehabilitation program directors reported that leadership and stress management were the most important skills for chief residents.2 However, only 25% of programs represented by respondents provided formal training in these areas.

Program directors often rely on effective partnering with their chief residents for a variety of tasks including personnel issues and the ability to successfully manage and, at times, transform residency programs. Considering that these relationships begin anew each academic year, strong interpersonal skills are required for an effective partnership. A highly effective team of program director and chief resident(s) 5 be instrumental to program director job satisfaction and residency program success. To date, little has been written about this critical partnership.

This article describes a novel workshop that paired program directors with their incoming chief residents to facilitate improved partnership. We describe the workshop, including results from the chief resident and program director focus groups on expectations of each other in their respective roles. We also present results from a follow-up survey of workshop participants.

Methods

Chief Resident-Program Director Relationship-Building Workshop

To begin to address the critical partnership between program directors and chief residents, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) sponsored a full-day workshop for residency program directors and their incoming chief residents at the ACGME Educational Conference in March 2010. Participation in this inaugural workshop was limited to residency program leaders and chief residents from residency programs where the program director was a current or past recipient of the Parker J. Palmer Courage to Teach award. The goals of this workshop were to allow program directors and their future chief residents to (1) learn what behaviors are desired and/or disliked in maximizing an effective working relationship, (2) develop an understanding for each other's leadership style and self-management strengths and weaknesses, and (3) establish a basis for more effective collaboration in the management of the residency program.

The first half of the workshop focused on self-discovery and co-discovery of leadership and management preferences, using experiential learning techniques.4 The Myers-Briggs Personality Inventory (MBTI Trust, Inc., Gainesville, FL) was utilized as a launching point for a discussion of differences in preferences around personal organizational styles, communication preferences and focus of energy (introversion versus extraversion), reaction to change, and strategies used for decision making. The second half of the workshop was designed to open communication between chief residents and program directors about feedback and expectations of each other in this year-long partnership. Chief residents discussed with each other the potential problems and improvements in working with their program directors. Likewise, in small groups, program directors discussed their expectations of and frustrations with chief residents. Responses were captured on flip charts. The small groups were brought back together, and chief residents and program directors from different institutions were paired to develop action steps, and then they discussed these steps with their own counterpart (chief resident or program director from the same institution). Summarized results of common themes from these small groups are presented below. Finally, participants were asked to complete an anonymous evaluation of the workshop at its conclusion.

Survey Methods

In 11 2010, the 32 workshop participants were sent an anonymous internet-based survey to determine whether there had been lasting impact of this workshop on the partnership between the chief residents and their residency program leadership. Eight questions asked participants to rate the impact of the workshop on leadership and work relationships on a 4-point scale (significantly increased/improved, moderately increased/improved, somewhat increased/improved, or did not increase/improve). Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) was used to summarize data into descriptive results. Given the small sample size and nature of the data, no tests of significance were performed.

Results

Participants expressed a high degree of satisfaction with the workshop, rating it an 8.5/10 points overall. Participants particularly found the in-depth discussion of personality styles helpful for thinking about how to work with one another and other colleagues in the coming year. Chief residents and program directors also commented on the importance of the opportunity to work in small groups together to discuss expectations and potential frustrations for the coming year.

Small Group Results

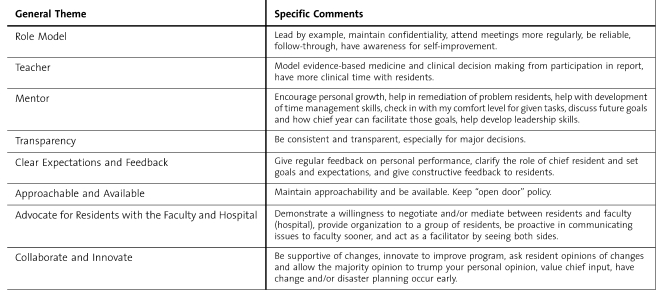

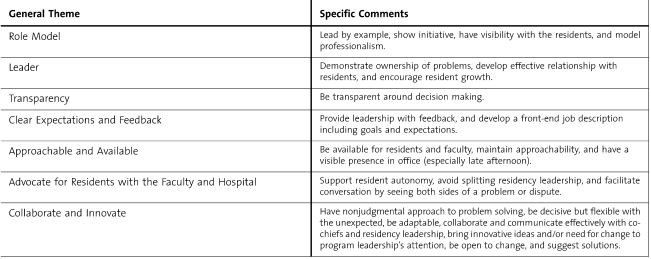

Analysis of flip chart responses from small groups of program directors and chief residents revealed some common themes. Both program directors and chief residents expect each other to act as a role model for the residents, be approachable and available, and to be transparent and as fair as possible in their decision-making processes. Both groups also wanted feedback on performance and wanted clear expectations from each other for roles and responsibilities. Finally, both chief residents and program directors identified the need to be innovative and supportive of changes in the program. When chief residents were asked what they would like to see more of in a program director, themes of professionalism, excellence in teaching and mentoring, and reliability and transparency were common (table 1). When program directors were asked what they would like to see more of in chief residents, they identified leadership, openness to change and innovation, and effective communication and collaboration as important themes (table 2).

TABLE 1.

Qualities Chief Residents Would Like To See more of in Residency Program Directors

TABLE 2.

Qualities Program Directors Would Like To See more of in Chief Residents

Survey Results

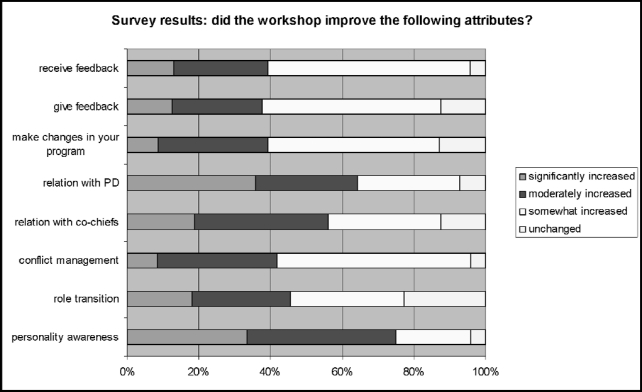

The postworkshop survey was completed by 24 of the 32 workshop participants (response rate, 75%). Results are summarized in the figure. Of the respondents, 14 respondents (58%) were chief residents, and 10 respondents (42%) were senior faculty (program director, associate program director, or education chair). Most respondents (75% overall, 79% of chief residents, 70% of faculty) indicated that the workshop moderately or significantly increased their awareness of the different aspects of their personality and its effect upon others. Workshop participants also stated that the workshop improved their ability to make a transition to a leadership role and to effectively manage conflicts. Similarly, 38% of respondents (55% of chief residents, 10% of faculty) stated that the workshop moderately or significantly improved their ability to give feedback and receive feedback. Respondents reported that participation in this workshop improved their relationships with their co-chiefs and program directors, with 9 of the 14 chief residents reporting that participation moderately or significantly improved their relationship with their program director.

FIGURE.

Impact of Workshop Participation On Leadership And Work Relationships

While both groups indicated that they benefitted from the workshop, chief residents reported a higher perceived benefit than program directors. This is likely due to the fact that for the chief residents, the workshop provided novel educational content.

Discussion

Our novel 1-day workshop aimed to give residency program directors and associate program directors and their incoming chief residents tools to increase self-awareness, leadership skills, and feedback skills in order to improve their working relationship. This was accomplished through a series of exercises that incorporated experiential learning methods with small group discussions. We believe an effective partnership between the chief resident and residency leadership is critically important to a residency program's success, chief residents' development as future leaders, and the residency program director's job satisfaction. To date, there is little information in the literature about the characteristics of an effective program director-chief resident partnership or how to facilitate collaboration between the 2 roles, which collectively are important to program quality and resident satisfaction.

Interestingly, in small group discussions, chief residents and program directors independently identified similar expectations for one another, centered on acting as program leaders and role models with high levels of professionalism. Communication and collaboration, innovation, and resident advocacy emerged strongly from both groups as characteristics they would like to see more of in each other. While chief residents also identified teaching as an important characteristic of a program director, this group of program directors did not identify teaching as something they would like to see more of in their chief residents. There are a number of explanations for this finding; however, it is likely in part an acknowledgement of the challenges of the chief resident's role in terms of leadership, management, and administrative tasks for which residency does not offer significant preparation compared with teaching skills.

Previous studies of the chief resident position identified similar expectations.5,6 Program directors expected chief residents to be leaders within the residency program and facilitators of change, mediators of conflict, and advocates for the residents.2,3,5,6 One study likened the chief resident role to that of a “middle manager” with up work (satisfying the needs and requirements of the Residency Director and institution with whom they work), down work (teaching, counseling, and support of residents), lateral work (working with other middle managers including faculty, nursing managers, etc.), and internal work (self-reflection and work with co-chief residents to determine work balance and how the work is going).7 It is clear from this workshop that through experiential learning exercises that enhance communication and leadership skills, program directors and chief residents perceive an improvement in their ability to manage conflict, work together, and give and receive feedback more effectively.

Limitations

We have described a 1-day workshop for a highly selective group of program directors and their chief residents who volunteered to come to a national meeting and participate in this workshop. Limitations of our study include our small sample size and the fact that our follow-up used a nonvalidated survey. Our results 5 not be generalizable to other chief resident courses or residency programs. We resurveyed participants 8 months after the workshop to assess for a lasting impact but did not collect third-party assessments to corroborate whether participation resulted in an actual enhancement of skills. Finally, we could not quantify whether our joint workshop for chief residents and program directors had an added benefit over holding a separate workshop for chief residents only.

Conclusions

Residency program directors and their incoming chief residents benefit from formal preparation for their year-long partnership and also perceive benefit from learning more about their individual styles and how their personalities impact those with whom they work. An effective partnership between the chief resident and residency director is critical to the continued success of residency education, and institutions should seek ways to support formal preparation for this partnership. The desirable characteristics developed by program directors and chief residents during the workshop (tables 1 and 2) 5 be useful for adoption or adaptation by residency programs.

Footnotes

Heather A. McPhillips, MD, MPH, Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Associate Residency Director, Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine; John G. Frohna, MD, MPH, Professor of Pediatrics and Medicine; Program Director for Pediatrics; Vice Chair for Education Department, University of Wisconsin; M. Hassan Murad, MD, MPH, Associate Professor and Preventive Medicine Residency Program Director 5o Clinic, Rochester; Maneesh Batra, MD, MPH, Assistant Professor - Department of Pediatrics, Division of Neonatology; Associate Director - Pediatric Residency Program; Adjunct Assistant Professor - Department of Global Health, University of Washington School of Medicine; Mukta Panda, MD, FACP, Professor and Chair, Program Director for Transitional Year, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga; Marsha A. Miller, MA, Associate Vice President, Office of Resident Services, ACGME; Timothy P. Brigham, MDiv, PhD, Chief of Staff, Senior Vice President Department of Education, ACGME; and Robert A. Doughty, MD, PhD, Senior Scholar for Experiential Learning and Leadership Development, ACGME.

References

- 1.Susman J, Gilbert C. Family medicine residency directors' perceptions of the position of chief resident. Acad Med. 1992;67:212–213. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199203000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain S. S, DeLisa J. A, Campagnolo D. Chief residents in physiatry. Expectations v training. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;72:262–265. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris T, Susman J, Gilbert C. Do program directors and their chief residents view the role of chief resident similarly. Fam Med. 1996;28:343–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doughty R. A, Williams P. D, Brigham T. P, Seashore C. Experiential leadership training for pediatric chief residents: impact on individuals and organizations. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:300–305. doi: 10.4300/JGME-02-02-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warner C. H, Rachal J, Breitbach J, Higgins M, Warner C, Bobo W. Current perspectives on chief residents in psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31:270–276. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.31.4.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young M. A, Stiens S. A, Hsu P. Chief residency in PM&R. A balance of education and administration. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;75:257–262. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg D. N, Huot S. J. Middle manager role of the chief medical resident: an organizational psychologist's perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1771–1774. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0425-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]