Abstract

(See the editorial commentary by Beck, on pages 172–3, and the article by Kim et al, on pages 244–51.)

For the first time, obesity appeared as a risk factor for developing severe 2009 pandemic influenza infection. Given the increase in obesity, there is a need to understand the mechanisms underlying poor outcomes in this population. In these studies, we examined the severity of pandemic influenza virus in obese mice and evaluated antiviral effectiveness. We found that genetically and diet-induced obese mice challenged with either 2009 influenza A virus subtype H1N1 or 1968 subtype H3N2 strains were more likely to have increased mortality and lung pathology associated with impaired wound repair and subsequent pulmonary edema. Antiviral treatment with oseltamivir enhanced survival of obese mice. Overall, these studies demonstrate that impaired wound lung repair in the lungs of obese animals may result in severe influenza virus infection. Alternative approaches to prevention and control of influenza may be needed in the setting of obesity.

In March 2009, a novel influenza A virus subtype H1N1 strain derived from 2 preexisting swine influenza virus lineages was identified in Mexico and the United States [1]. By June 2009, the World Health Organization indicated the start of the first influenza pandemic of the 21st century. The actual number of cases worldwide is unknown as most cases were not laboratory confirmed. However, estimates suggest that the total number of cases was on the order of several tens of millions worldwide [2–4]. Although most illness associated with infection was mild and self-limiting [4], several high-risk groups, including persons with chronic illnesses, pregnant women, and immunocompromised patients, experienced more severe infection [4–6]. Strikingly, however, obesity was also shown to be a risk factor for developing severe influenza disease [3, 5–8]. Severe or morbid obesity was associated with a relative risk of severe disease or death between 5 and 15 times greater than that of the rest of the population [9].

Obesity is increasing epidemically worldwide [10, 11]. Although the role of obesity as a risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality through its association with cardiovascular disease and diabetes is well documented [12–14], the past decade has highlighted that obesity is also a risk factor for respiratory diseases (reviewed in [15]). The exact mechanisms are unclear; however, obesity is associated with a state of chronic systemic inflammation that may promote airway hyperresponsiveness [15]. A recent study describing the clinicopathologic characteristics of confirmed pandemic 2009 H1N1-associated deaths found that 72% of the cases were in obese adults and adolescents [8]. Others, including groups in Chile, Canada, and Mexico, reported that obesity was one of the most frequently identified underlying conditions in fatal pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza cases in patients over 20 years of age [16]. Given the worldwide increase in obesity, there is a pressing public health need to understand the pathogenic mechanisms underlying poor outcomes from influenza infection in this expanding population. The goal of the present study was to fill this gap in knowledge by examining the severity of pandemic 2009 H1N1 virus in obese animals and evaluate antiviral therapy effectiveness with the neuraminidase (NA) inhibitor oseltamivir. Our data confirm that obese animals are more susceptible to severe influenza virus infection. Increased pathogenicity appears to be due to impaired wound repair in the infected lungs of obese animals, leading to edema rather than increased replication or spread of the virus. Importantly, oseltamivir protected obese animals. Overall, these studies demonstrate that the enhanced inflammation and lack of wound repair in obese mice may lead to the development of more severe influenza infection but that antiviral therapies are effective in this population.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

All procedures involving animals were approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals

Genetically Obese Mice

Eight-week-old lean male C57BL/6J (∼21 g) and B6.V-Lepob/J (genetically obese [ob/ob]; ∼53 g) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME).

Diet-Induced Obese Mice

Eleven-week-old male C57BL/6J (∼21 g) and preconditioned diet-induced obese (DIO; ∼35 g) mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IA). The mice were preconditioned by feeding C57BL/6 mice either a traditional mouse diet or a Tekland high-fat diet (60% Kcal from fat; TD.06414, Tekland, Harlan Laboratories) from the time of weaning. All mice had free access to food and water.

Viruses and Infection

A/California/04/2009 (CA/09, pandemic H1N1 [pH1N1]) and A/Hong Kong/1/1968 2:6 (HK68, influenza A virus subtype H3N2 [17]) viruses were propagated in the allantoic cavity of 10-day-old specific pathogen-free embryonated chicken eggs. At 48–72 hours postinfection, allantoic fluid was harvested, clarified by centrifugation, and stored at −70°C. Viral titers were determined by 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) analysis in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells as described elsewhere [18] and evaluated by the method of Reed and Muench [19]. For infections, mice were lightly anesthetized by isofluorane inhalation and intranasally inoculated with 105 TCID50 of CA/09 in 25 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.1 median lethal dose [MLD50]) or 6.3 × 105 TCID50 of HK68 in 100 μL PBS (0.2 MLD50).

Flow Cytometry

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples were collected on days 3–14 postinfection from 2 control and 3 infected mice, and flow cytometry was performed. Briefly, single-cell populations were collected by mild centrifugation (100g, 10 minutes), resuspended in red blood cell lysis solution (0.15 mol/L NH4Cl, 1 mmol/L KHCO3, and 0.1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), washed with PBS, and aliquoted at 1.0 × 104 cells per sample. Aliquots then were incubated with 4% normal rat serum and anti-Fc block (CD16/32; eBioscience Inc, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cell populations were stained with Ly-6G, CD11b, CD11c, F4/80, CD86, NK1.1, CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD69 antibodies directly conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647, Alexa Fluor 700, fluorescein isothiocyanate, phycoerythrin, and APC-eFluor (eBioscience Inc) combined with the violet LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) was used for cellular acquisition of 10 000 total live, singlet events per sample, and results were analyzed using FlowJo Flow Cytometry Analysis software.

Quantitation of Viral Titers

On days 3–14 postinfection, lungs were removed from 2 control and 3 infected mice per group, homogenized in minimum essential medium, and stored at −80°C. Titers determined on individual mice were performed in triplicate by TCID50 analysis in MDCK cells [18] and evaluated by the method of Reed and Muench [19].

Luminex Cytokine Arrays

Briefly, lung homogenates were collected and cytokine/chemokine levels determined using the Milliplex Mouse 22-Plex Cytokine Detection Systemmouse cytokine kit (LINCO Research Inc, Saint Charles, MO) on a Luminex100 reader (Luminex Corp, Austin, TX). Data were calculated using a calibration curve obtained in each experiment using the respective recombinant proteins as per manufacturer’s instructions. Values were normalized to equivalent protein concentrations as determined by BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, IL) and calculated as the mean of replicates of 6.

Histopathology

On days 3–14 postinfection, deeply anesthetized mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunohistochemical staining was performed by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Veterinary Pathology Core Facility.

Oseltamivir Treatment

Oseltamivir phosphate (oseltamivir) was administered by oral gavage (100 μL/mouse) twice daily for 5 days to groups (n = 5) at dosages of 20 and 100 mg/kg/day. Control (infected untreated) mice received sterile PBS on the same schedule. Six hours after receiving the first dose of oseltamivir, the mice were inoculated with 105 TCID50 of CA/09 in 25 μL PBS [20].

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of survival between groups of mice was performed with the log rank χ2 test on the Kaplan–Meier survival data. Comparison of the cellular, cytokine, and viral titer data was performed using analysis of variance for multiple comparisons or Student t test for pairwise comparisons with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Error bars represent standard deviation, and statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

RESULTS

Survival of Obese Mice Challenged With Pandemic H1N1 and H3N2 Influenza Viruses

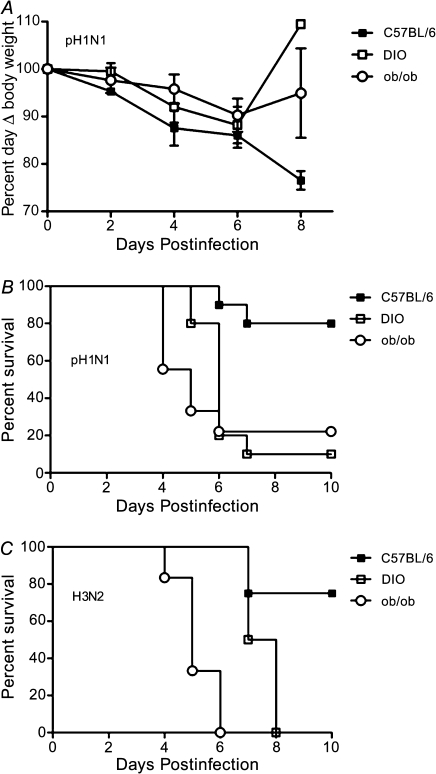

Epidemiological studies suggested that obesity was a risk factor for developing severe 2009 H1N1 influenza infection [3, 5–9]. To evaluate the relevance of obesity as a risk factor for developing severe influenza and begin defining underlying mechanisms, strain-matched lean (C57BL/6, n = 28), and DIO (n = 28) or ob/ob (n = 28) mice were lightly anesthetized and intranasally inoculated with CA/09 pH1N1 virus and monitored for morbidity and mortality. Both genetically and diet-induced obese mice were used to more closely mimic causes of human obesity. The pH1N1 virus-infected mice in all groups lost ∼10%–15% of their starting weight by day 6 postinfection with the lean mice continuing to lose weight at day 8 postinfection (Figure 1A). Despite a lack of significant weight loss, obese mice rapidly succumbed to pH1N1 infection (Figure 1B). Within 6 days postinfection, 80% of the infected obese mice died as compared with ∼20% of the lean controls (P < .01 for DIO and P < .003 for ob/ob). The enhanced mortality did not differ with the type of obesity and was not specific to the 2009 pH1N1 influenza virus. Obese mice infected with the 1968 HK68 H3N2 virus also succumbed more readily to infection (Figure 1C). With this virus, 100% of the ob/ob mice died by day 6 postinfection, whereas the DIO had a slight, although significant delay in mortality, with 100% dying by day 8 postinfection (P < .004). Similar results were observed with highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses (data not shown). These results suggest that obese mice are more likely to develop severe influenza infection.

Figure 1.

Obese mice have increased mortality during influenza infection. C57BI/6N (n = 28) and diet-induced obese (DIO, n = 28) or genetically obese (ob/ob, n = 28) mice were lightly anesthetized and intranasally infected with (A, B) 105 TCID50 A/California/04/2009 H1N1 (CA/09, pH1N1) or (C) 6.3 × 105 TCID50 A/Hong Kong /68 (HK68, H3N2) influenza virus and monitored for weight loss and mortality. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Abbreviations: pH1N1, pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1; H3N2, influenza A virus subtype H3N2.

Immune Cell Infiltration in Obese Mice

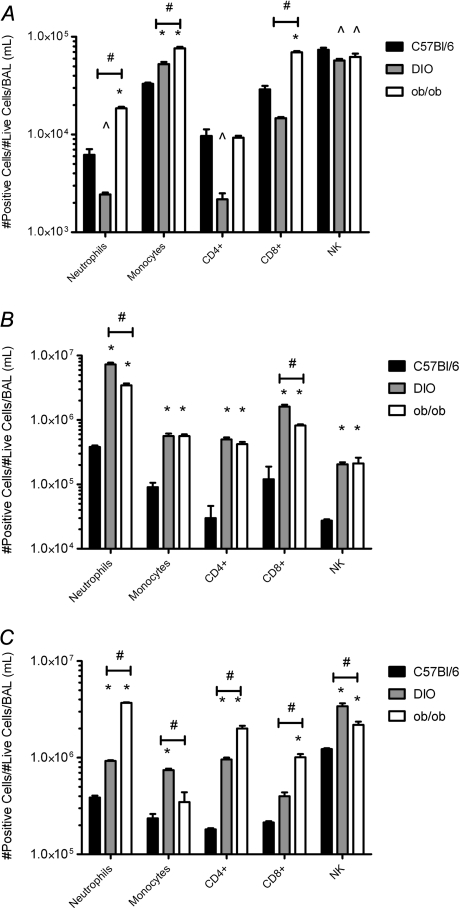

Obesity is associated with chronic low levels of inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness (reviewed in [15, 21]), so we further examined lung inflammation. Immune cell infiltration into the airways was monitored by BAL at days 3, 6, and 14 postinfection. At day 3 postinfection, infiltrating monocyte (CD11b+, CD11c+, Ly-6g−, and CD86+) levels increased in the pH1N1-infected obese mice as compared with lean mice (P < .01; Figure 2A). The infected ob/ob mice also had elevated levels of neutrophils (CD11bhi, CD11c−, Ly6ghi, and F4/80−) and CD8+ T cells (CD3+, NK1.1−, CD8+, and CD4−; P < .01; Figure 2A). By day 6 postinfection, all the cell types monitored were significantly increased in the obese mice with the most significant elevation being in neutrophil numbers (P < .001; Figure 2B). Neutrophil numbers were ∼9-fold higher in the ob/ob and ∼20-fold higher in the DIO mice (3.5 × 106 and 7.2 × 106, respectively, as compared with 3.8 × 105 cells in lean mice). The increased cellular infiltration was still evident at day 14 postinfection in the obese mice that survived viral infection (Figure 2C). The elevated cellular infiltration was likely due to amplified levels of the chemokines granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), CXCL10 (IP-10), CXCL1 (KC), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) present in the lungs of the infected obese mice (Table 1). This was accompanied by elevated levels of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 6 (IL-6). We found significant decreases in the levels of the immunoregulatory protein transforming growth factor β at day 3 postinfection and interferon γ at day 6 postinfection as compared with both uninfected control and infected lean mice (Table 1), suggesting further dysregulation of immune responses.

Figure 2.

Changes in immune cell infiltrates in the lungs of obese mice infected with influenza virus. BAL samples were collected on days 3 (A), 6 (B), and 14 (C) post-pH1N1 infection from 2 control and 3 infected mice and flow cytometry performed. Briefly, single-cell populations were collected and single-cell populations were stained with Ly-6G, CD11b, CD11c, F4/80, CD86, NK1.1, CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD69 antibodies directly conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647, Alexa Fluor 700, fluorescein isothiocyanate, phycoerythrin, APC-eFluor combined with LIVE/Dead Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain Kit. Results are graphed as the number of positive cells per number of lives cells per 1 mL BAL fluid. Error bars represent SD, asterisk (*) indicates significant increase, and (^) indicates significant decrease in cell numbers as compared with C57BI/6 lean infected mice. Number symbol (#) represents significant differences between DIO and ob/ob infected mice.

Abbreviations: BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; pH1N1, pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1.

Table 1.

Pulmonary Expression of Cytokines/Chemokines in Uninfected and pH1N1-Infected Obese Micea

| Cytokine/Chemokine | Day 3 Uninfected Lean | Day 3 Infected DIO | Day 6 Uninfected ob/ob | Day 6 Infected Lean | Day 3 Uninfected DIO | Day 3 Infected ob/ob | Day 6 Uninfected Lean | Day 6 Infected DIO | Day 3 Uninfected ob/ob | Day 3 Infected Lean | Day 6 Uninfected DIO | Day 6 Infected ob/ob |

| G-CSF | 9 ± 2 | 11 ± 3 | 1 ± 0.2 | 60 ± 4 | 3441 ± 635 | 2518 ± 401 | 4 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | 1 ± 0.1 | 95 ± 18 | 182 ± 80 | 561 ± 101 |

| IL-6 | 0.4 ± 0 | 1 ± 0.3 | 745 ± 218 | 40 ± 1 | 1074 ± 144 | 569 ± 198 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.7 | 1 ± 0.2 | 650 ± 76 | 1217 ± 87 | 442 ± 155 |

| CXCL10 | 80 ± 8 | 32 ± 10 | 17 ± 9 | 169 ± 41 | 607 ± 89 | 745 ± 150 | 18 ± 4 | 18 ± 5 | 14 ± 0.8 | 262 ± 64 | 161 ± 1 | 68 ± 3 |

| CXCL1 | 20 ± 9 | 25 ± 2 | 19 ± 6 | 22 ± 8 | 102 ± 17 | 724 ± 153 | 5 ± 4 | 225 ± 60 | 8 ± 2 | 54 ± 7 | 51 ± 15 | 68 ± 3 |

| MCP-1 | 4 ± 0.3 | 2 ± 0.2 | 2 ± 0.5 | 6 ± 0.04 | 80 ± 21 | 58 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.1 | 1 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 0.2 | 10 ± 0.04 | 48 ± 5 | 17 ± 6 |

| TGF-β | 2348 ± 375 | 1790 ± 103 | 1984 ± 390 | 4237 ± 373 | 585 ± 277 | 390 ± 279 | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| IFN-γ | … | … | … | … | … | … | 15 ± 4 | 171 ± 1 | 468 ± 1 | 170 ± 16 | 34 ± 4 | 8 ± 0.3 |

Abbreviations: pH1N1, pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1; DIO, diet-induced obese; ob/ob, genetically obese; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IL-6, interleukin 6; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; TGF- β, transforming growth factor β; IFN-γ, interferon γ.

Mean concentration (ρg/mL) ± SD from 6 mice.

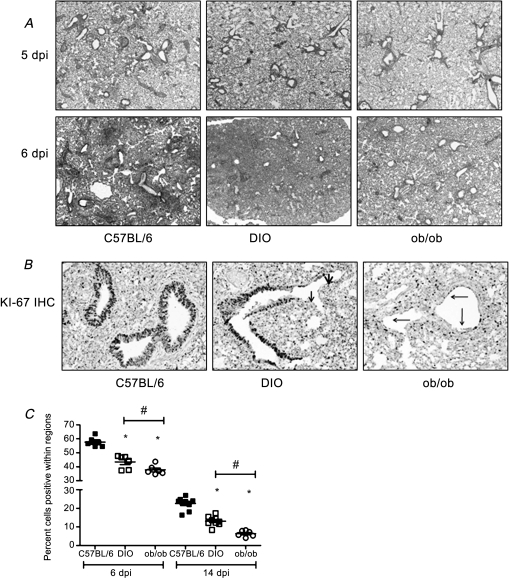

Histopathology in Lungs of Obese Mice Infected With pH1N1 Influenza Virus

Histologically, there were no significant differences among the lean, DIO, and ob/ob pH1N1-infected mice on days 2 and 3 postinfection (data not shown), and by day 5 postinfection, all of the mice had increased interstitial inflammation and moderate perivascular cuffing by lymphocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3A). At day 6 postinfection, the overall severity and extent of inflammation in the lungs of mice in all 3 groups increased, although there were differences in the severity. In lean mice, alveoli frequently contained abundant granulocytes and cell debris, and perivascular cells were composed largely of macrophages and granulocytes accompanied by variable numbers of lymphocytes (Figure 3A). The lungs of infected DIO mice had similar lesions but showed a greater extent and severity of granulocytic inflammation and protein exudates in alveoli (Figure 3A). Unexpectedly, the ob/ob mice showed significantly less interstitial and alveolar inflammation, yet there was increased edema (Figure 3A). However, at day 14 postinfection, there was still significant inflammation in the lungs of the obese mice in contrast to the lean mice (Figure 6A), suggesting that the obese animals had delayed resolution of lung inflammation following influenza virus infection. No lesions were seen outside the lung.

Figure 3.

Decreased cell proliferation in the lungs of obese mice infected with influenza virus. At days 5, 6, and 14 postinfection, lungs were collected from deeply anesthetized and formalin-perfused mice and paraffin-embedded. Sections (4 μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A) or for the cell proliferation marker Ki-67 (B). Representative pictures of each group are shown at 4× (A) and 20× (B) magnification. C, Digital images of the Ki-67 slides were obtained, and the percentage of positive nuclei in 4 random sections of the lung for each animal were determined with ImageScope using a nuclear-based algorithm. Error bars represent SD, and asterisk (*) indicates significant decrease in percent cells positive as compared with C57BI/6N lean infected mice. Number symbol (#) represents significant differences between DIO and ob/ob infected mice.

Abbreviations: dpi, days postinfection; DIO, diet-induced obese; ob/ob, genetically obese.

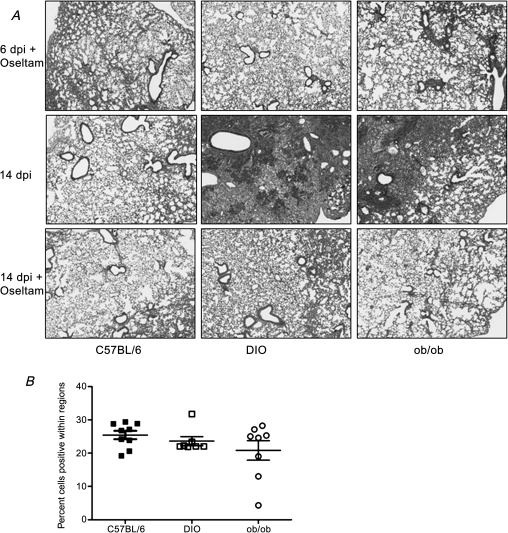

Figure 6.

Decreased lung histology and increased Ki-67 staining in the lungs of influenza virus–infected mice treated with oseltamivir. A, At days 6 and 14 postinfection, lungs were collected from deeply anesthetized and formalin-perfused mice and paraffin-embedded. Sections (4 μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and representative pictures of each group are shown at 20× magnification. B, Digital images of the Ki-67 slides were obtained, and the percentage of positive nuclei in 4 random sections of the lung for each animal were determined with ImageScope using a nuclear-based algorithm. Error bars represent SD.

Abbreviations: dpi, days postinfection; Olestam, oseltamivir; DIO, diet-induced obese; ob/ob, genetically obese.

To further evaluate the effect of obesity on lung pathology, we next examined epithelial proliferation using the cellular marker for proliferation Ki-67 [22]. A striking finding was the marked reduction in the extent of epithelial regeneration in the infected obese animals as determined by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 3B). At day 6 postinfection, evidence of epithelial regeneration was widespread in the bronchioles of lean mice, whereas the majority of the bronchiolar surfaces in DIO mice remained denuded of epithelial covering. The relatively few bronchioles that showed regeneration in DIO mice were typically only partially covered by attenuated epithelial cells. The reduction in epithelial regeneration was also severe in the ob/ob-infected mice. Although some bronchioles were denuded of epithelium, much of the luminal surface of bronchioles were covered by a discontinuous layer of regenerating epithelium, which in many bronchioles appeared as a flattened attenuated single layer of cells. Quantitative analysis showed a decrease in Ki-67 staining from ∼59% positive cells in lean mice to ∼43% in DIO mice and 38% in ob/ob mice (P < .005; Figure 3C). The ob/ob infected mice also had significantly less Ki-67 staining than did the DIO mice (P < .05). The decreased Ki-67 staining in the obese mice was still evident at day 14 postinfection, suggesting an impaired wound repair response (Figure 3C).

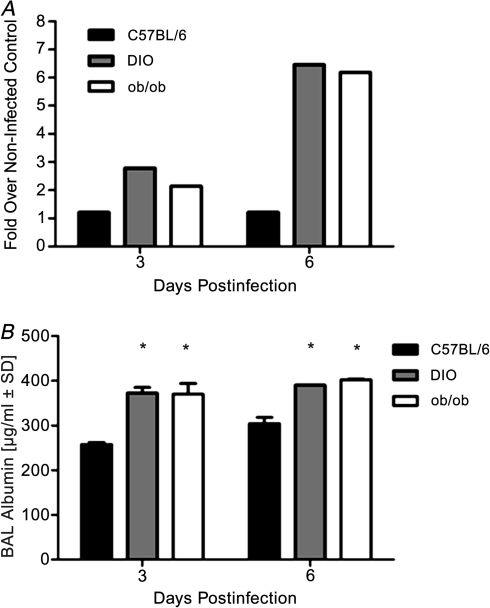

Increased Protein Levels in the Lungs of Obese Mice

To determine if the increased inflammation and edema in the obese mice was associated with elevated pulmonary barrier permeability, we determined BAL fluid total protein concentration (Figure 4A). Results are shown as the fold over noninfected controls. Total protein levels in the BAL fluid were significantly increased in the lungs of obese mice compared with lean animals. At day 6 postinfection, the obese animals had ∼0.5 mg protein in their BAL fluid as compared with 0.1 mg in lean mice (Figure 4A). To clarify that this was an effect on barrier dysfunction, permeability was directly assessed by measuring BAL albumin levels by ELISA [23, 24]. BAL albumin levels were significantly enhanced in the infected obese mice (P < .001; Figure 4B), suggesting that there is a defect in barrier permeability potentially leading to the edema. We hypothesize that this is mediated by the delayed repair of epithelial surfaces in the airways and alveoli.

Figure 4.

Influenza virus-infected obese mice have increased lung protein and albumin levels. BAL samples were collected on days 3 and 6 post-pH1N1 infection from 2 control and 3 infected mice total protein concentrations determined by BCA assays (A) or albumin levels by enzyme-linked immunoassay (B). Error bars represent standard deviation, and asterisk (*) indicates significant increase in BAL albumin levels as compared with C57BI/6N lean infected mice.

Abbreviations: BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; pH1N1, pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1; BCA, bradford colorimetric assay; DIO, diet-induced obese; ob/ob, genetically obese.

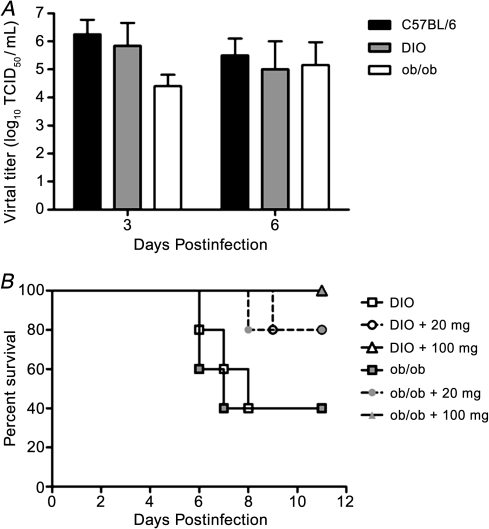

Increased Pathogenicity in Virus Infected Obese Mice Is Independent of Enhanced Viral Replication Yet Oseltamivir Is Effective

The enhanced disease severity in the pH1N1-virus–infected obese mice was not due to elevated viral titers. There were no significant differences in viral titer at either time postinfection (Figure 5A), and by day 10 postinfection, all surviving mice had cleared the virus from their lungs (data not shown). Further, no virus was found outside the lungs. However, the interaction of the virus with the obesogenic environment was required for the enhanced disease severity since administration of oseltamivir protected the mice from lethal disease (Figure 5B). Briefly, mice were administered 20 mg/kg/day (a drug regimen that approximated the recommended human regimen) and 100 mg/kg/day of the drug by oral gavage 6 hours before inoculation with pH1N1 influenza virus. Both DIO and ob/ob virus-inoculated, untreated control mice showed high mortality rates; only 40% of the mice survived the infection, respectively. In contrast, 80% of the mice treated with 20 mg/kg/day oseltamivir survived viral infection, increasing to 100% survival in the mice administered 100 mg/kg/day (Figure 5B). No statistically significant differences in weight were observed between oseltamivir-treated and untreated control obese mice (results not shown). These studies demonstrate that a dose of oseltamivir equivalent to that recommended for humans reduces the enhanced severity of influenza infection observed in obese mice. However, an increased dose was required for complete protection. These results correlate with the observation that the severity of severe pH1N1 2009 infections in humans were reduced when oseltamivir treatment was employed [25].

Figure 5.

Enhanced lethality in obese mice is independent of increased viral titers, but mice can still be protected with oseltamivir. A, At 3 and 6 days postinfection, lung homogenates were monitored for viral titers by TCID50 analysis on MDCK cells. B, pH1N1 DIO or ob/ob mice (n = 5 per group) were orally administered either 20 or 100 mg/kg oseltamivir virus 8 hours preinfection, then every 12 hours after infection with 105 TCID50 pH1N1 influenza virus for 5 days, and then monitored for morbidity over 12 days. Error bars represent SD.

Abbreviations: TCID50, 50% tissue culture infectious dose; MDCK, Madin-Darby canine kidney; DIO, diet-induced obese; ob/ob, genetically obese; pH1N1, pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1.

There was very little difference in lung viral titers in lean versus obese mice (Figure 5A), yet the mice were protected by oseltamivir. To better understand the mechanism of protection, viral titers, lung histology, and Ki-67 staining were assessed. In contrast to the untreated mice (Figure 5A), all mice administered oseltamivir had cleared the virus by day 6 postinfection (data not shown) and there was decreased lung inflammation (Figure 6A) as compared with untreated mice (Figure 3A). This was even more evident at day 14 postinfection where there was still significant inflammation in the lungs of the untreated obese mice in contrast to the lean mice (Figure 6A). Oseltamivir treatment led to lessened inflammation in the obese mice with Ki-67 levels similar to lean mice. These studies suggest that influenza virus infected obese mice have prolonged inflammation and impaired wound repair independent of increased viral titers that can be alleviated by treatment with oseltamivir.

DISCUSSION

Obesity has become a worldwide epidemic. It is estimated that >30% of adults in the United States are overweight or obese [26, 27]. Obesity can lead to a variety of serious conditions, and more recent evidence suggests that it is also associated with impaired immune function and increased susceptibility to a number of different pathogens (reviewed in [21]), including influenza virus [3, 28–30]. Experimental studies in obese animals demonstrated augmented mortality during sepsis [31] and increased viral myocarditis during coxsackievirus B4 infection [32].

In the present study, we show that both genetically and diet-induced obese animals are more likely to develop severe influenza infection. Our results demonstrated that the increased severity was independent of the viral strain and appeared to be due to impaired wound repair in the lungs of infected obese animals leading to edema, and not to increased lung replication of the virus or spread outside the lungs. Importantly, adjusted oseltamivir treatment based on body weight reduced severity of infection and protected obese animals from death.

Our findings complement previous work using the mouse-adapted laboratory strain A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1; PR8). These studies demonstrated that 50% of PR8-infected DIO mice succumbed to infection by day 8 postinfection [33]. Similar to our data, they found no difference in viral titers in the obese animals as compared with nonobese mice [33]. In that study, infection in obese animals was associated with depressed cytokine levels, reduced natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity, and selective impairment in dendritic cell function [34]. Further, they demonstrated that obesity led to alterations in the T-cell populations that may ultimately be damaging to the host [35, 36]. However, the mechanism for the increased mortality during the primary infection was not defined and protection by antiviral therapies was not addressed.

To understand the mechanism of increased mortality during primary infection, we evaluated lung inflammation and function. Although there were no remarkable difference in histopathology at day 3 postinfection, the obese mice had increased numbers of infiltrating monocytes and decreased numbers of NK cells as compared with nonobese animals. The increase in monocytes could be due to the increased expression of the chemokines G-CSF, CXCL1, CXCL10, and MCP1 in the lungs of obese mice. Strikingly, there were remarkable differences in the infiltrating cell populations depending on the type of obesity. The infected DIO mice had significantly fewer infiltrating neutrophils and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as compared with either lean or ob/ob mice. The reason for these differences remains under investigation.

In contrast, by day 6 postinfection, the obese animals had significantly higher cellular infiltration in the lung that was not resolved by day 14 postinfection. Histologically, the DIO mice had the greatest extent and severity of granulocytic inflammation and protein exudates in alveoli as compared with lean mice. Although the ob/ob mice superficially appeared to have the least severe pulmonary lesions, with notably less interstitial and alveolar cellular infiltrates, mice in this group had the most extensive and severe pulmonary edema. Both obese groups had higher levels of protein and albumin in the lungs as compared with lean mice, suggesting a defect in barrier permeability. Exploring a potential mechanism, we found a notable reduction in the airway reepithelialization in the lungs of obese animals. The reduced extent of wound repair was most evident in the genetically obese animals, suggesting that either the increased weight of the animals or some underlying metabolic complications led to decreased wound healing. Delayed or impaired wound repair is a common finding in obesity. In humans, obesity leads to impaired cutaneous wound repair [37], and more extensive studies in obese animals demonstrated both impaired cutaneous [38] and gastric healing [39]. Studies are underway to determine the cause of the delayed wound repair and its role in disease severity.

An important question that remained unaddressed was how obesity-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes might affect the efficacy of therapeutic interventions in patients suffering from influenza virus [40, 41]. Thus, we treated obese animals with increasing doses of oseltamivir and monitored protection. Our studies showed that dosing at 20 mg/kg/day increased survival from 40% to 80% and that dosing 100 mg/kg/day afforded complete protection to obese animals. These findings suggest that oseltamivir should be effective in this highly susceptible population and are supported by several reports showing that oseltamivir is the drug of choice for treating severe pH1N1 infections, including those in obese patients [42–44].

In summary, we demonstrate that obesity is a risk factor for severe influenza infection in mice. Furthermore, we implicate poor lung wound healing leading to pulmonary edema suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome as a potential underlying mechanism, rather than a lack of viral control. This has implications for the prevention and treatment of influenza in obese persons. Obesity should be recognized as a risk factor requiring early antiviral therapy, and the pharmacokinetics and effectiveness of anti-influenza drugs should be carefully examined in this population. Clearly, further epidemiologic investigation of outcomes during seasonal influenza are indicated, and preparation for the next pandemic should take obesity into account.

Notes

Acknowledgments.

The authors gratefully acknowledge members of the Schultz-Cherry lab and the expert technical assistance of Pamela Freiden and Brad Seufzer. They thank Drs. Erik Karlsson, Andrew Burnham, Troy Cline, Nicholas van de Velde, Elaine Tuomanen, and Pamela McKenzie for discussions and critical review of the manuscript, Sean Savage and the staff in the St. Jude Animal Research Center and the Veterinary Pathology core facility. The NA inhibitor oseltamivir phosphate was provided by Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd.

Financial support.

This work was supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Gilliam Fellowship to K. O. B. and in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) contract HHSN266200700005C and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Potential conflicts of interest.

All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Garten RJ, Davis CT, Russell CA, et al. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science. 2009;325:197–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1176225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Presanis AM, De Angelis D, Hagy A, et al. The severity of pandemic H1N1 influenza in the United states, from April to July 2009: a Bayesian analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz E, Rodriguez A, Martin-Loeches I, et al. Impact of obesity in patients infected with new influenza A (H1N1) Chest. 2011;139:382–386. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerardin P, El Amrani R, Cyrille B, et al. Low clinical burden of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) infection during pregnancy on the island of La Reunion. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothberg MB, Haessler SD. Complications of seasonal and pandemic influenza. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:e91–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c92eeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louie JK, Acosta M, Winter K, et al. Factors associated with death or hospitalization due to pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in California. JAMA. 2009;302:1896–02. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsatsanis C, Margioris AN, Kontoyiannis DP. Association between H1N1 infection severity and obesity—adiponectin as a potential etiologic factor. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:459–60. doi: 10.1086/653842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill JR, Sheng ZM, Ely SF, et al. Pulmonary pathologic findings of fatal 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 viral infections. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:235–43. doi: 10.5858/134.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, et al. Clinical Aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. New Engl J Med. 2010;362:1708–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James WP. The fundamental drivers of the obesity epidemic. Obes Rev. 2008;9(suppl 1):6–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.James WP. WHO recognition of the global obesity epidemic. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(suppl 7):S120–6. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Despres JP. Intra-abdominal obesity: an untreated risk factor for Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathieu P, Pibarot P, Larose E, Poirier P, Marette A, Despres JP. Visceral obesity and the heart. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:821–36. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shore SA. Obesity, airway hyperresponsiveness, and inflammation. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:735–43. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00749.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaillant L, La Ruche G, Tarantola A, Barboza P. Epidemiology of fatal cases associated with pandemic H1N1 influenza 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14 doi: 10.2807/ese.14.33.19309-en. pii 19309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vigerust DJ, Ulett KB, Boyd KL, Madsen J, Hawgood S, McCullers JA. N-linked glycosylation attenuates H3N2 influenza viruses. J Virol. 2007;81:8593–600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00769-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson CM, Turpin EA, Moser LA, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta: activation by neuraminidase and role in highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001136. e1001136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Govorkova EA, Ilyushina NA, McClaren JL, Naipospos TS, Douangngeun B, Webster RG. Susceptibility of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses to the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir differs in vitro and in a mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3088–96. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01667-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsson EA, Beck MA. The burden of obesity on infectious disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:1412–24. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:311–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson MR, O'Dea KP, Dorr AD, Yamamoto H, Goddard ME, Takata M. Efficacy and safety of inhaled carbon monoxide during pulmonary inflammation in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inouey BE, Daniloff E, Kohno N, Hiwada K, Newman LS. Pulmonary epithelial cell injury and alveolar-capillary permeability in berylliosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:109–15. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9612043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith JR, Ariano RE, Toovey S. The use of antiviral agents for the management of severe influenza. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:e43–51. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c85229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherry B, Blanck HM, Galuska DA, Pan L, Dietz WH, Balluz L. Vital signs: state-specific obesity prevalence among adults—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huttunen R, Syrjanen J. Obesity and the outcome of infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:442–3. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nave H, Beutel G, Kielstein JT. Obesity-related immunodeficiency in patients with pandemic influenza H1N1. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:14–5. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Easterbrook JD, Dunfee RL, Schwartzman LM, et al. Obese mice have increased morbidity and mortality compared to non-obese mice during infection with the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2011;5:418–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strandberg L, Verdrengh M, Enge M, et al. Mice chronically fed high-fat diet have increased mortality and disturbed immune response in sepsis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webb SR, Loria RM, Madge GE, Kibrick S. Susceptibility of mice to group B coxsackie virus is influenced by the diabetic gene. J Exp Med. 1976;143:1239–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.5.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith AG, Sheridan PA, Harp JB, Beck MA. Diet-induced obese mice have increased mortality and altered immune responses when infected with influenza virus. J Nutr. 2007;137:1236–43. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith AG, Sheridan PA, Tseng RJ, Sheridan JF, Beck MA. Selective impairment in dendritic cell function and altered antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in diet-induced obese mice infected with influenza virus. Immunology. 2009;126:268–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karlsson EA, Sheridan PA, Beck MA. Diet-induced obesity in mice reduces the maintenance of influenza-specific CD8+ memory T cells. J Nutr. 2010;140:1691–7. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlsson EA, Sheridan PA, Beck MA. Diet-induced obesity impairs the T cell memory response to influenza virus infection. J Immunol. 2010;184:3127–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–29. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holcomb VB, Keck VA, Barrett JC, Hong J, Libutti SK, Nunez NP. Obesity impairs wound healing in ovariectomized female mice. In Vivo. 2009;23:515–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanigawa T, Watanabe T, Otani K, et al. Leptin promotes gastric ulcer healing via upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor. Digestion. 2010;81:86–95. doi: 10.1159/000243719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falagas ME, Athanasoulia AP, Peppas G, Karageorgopoulos DE. Effect of body mass index on the outcome of infections: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2009;10:280–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pai MP, Bearden DT. Antimicrobial dosing considerations in obese adult patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1081–91. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.8.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yokoyama T, Tsushima K, Ushiki A, et al. Acute lung injury with alveolar hemorrhage due to a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus. Intern Med. 2010;49:427–30. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bearman GM, Shankaran S, Elam K. Treatment of severe cases of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza: review of antivirals and adjuvant therapy. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2010;5:152–6. doi: 10.2174/157489110791233513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee EH, Wu C, Lee EU, et al. Fatalities associated with the 2009 H1N1 influenza A virus in New York city. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1498–504. doi: 10.1086/652446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]