Abstract

Communication failures during physician handoffs represent a significant source of preventable adverse events. Computerized sign-out tools linked to hospital electronic medical record systems and customized for neonatal care can facilitate standardization of the handoff process and access to clinical information, thereby improving communication and reducing adverse events. It is important to note, however, that adoption of technological tools alone is not sufficient to remedy flawed communication processes.

Objectives

After completing this article, readers should be able to:

Identify key elements of a computerized sign-out tool.

Describe how an electronic tool might be customized for neonatal care.

Appreciate that technological tools are only one component of the handoff process they are designed to facilitate.

Introduction

Communication errors are a leading underlying cause of adverse events and patient harm, and handoffs in patient care represent one source of such errors.1, 2, 3 The quantity and complexity of handoff information is increased in the intensive care environment, escalating the potential for errors in a process already described as a haphazard “precarious exchange”.4, 5, 6 The problem is exacerbated in the academic setting for two reasons: (1) residency work hour restrictions necessitate more frequent handoffs, increasing the risk of an incomplete or incorrect transfer of information;7, 8, 9 and (2) handoffs are most commonly conducted between junior trainees who have not commonly been given a formal structure or training for this process.10

The communication issues implicated as a root cause in greater than 80% of reported sentinel events represent an opportunity for the development of technological tools designed to improve the exchange of information.2, 11, 12 Specifically, computerized sign-out tools can facilitate standardization of the handoff process and access to clinical data.13, 14 In doing so, these electronic sign-out applications have the potential to improve communication and reduce preventable adverse events.15 The benefits of using computerized sign-out tools to facilitate the handoff process have been demonstrated in various medical disciplines16, 17, 18 including pediatrics19, 20 and the newborn intensive care unit (NICU).21

Electronic Sign-out Tools

Electronic sign-out tools can take several forms, including word processor or database manager documents, web-based systems, and tools integrated within a hospital’s electronic medical record (EMR). Regardless of the sign-out system used, certain essential information should be included. Patient demographics (name, medical record number, and location) are required for patient tracking. Information such as weight, medications, allergies, pertinent laboratory data, and provider-entered patient details (e.g. a prioritized problem list, brief narrative comments) are needed to summarize a patient’s clinical status and management. Information classified as either a to-do or an anticipatory guidance item is more likely to be communicated effectively,8 so these categories should be included as well. Finally, instructions to covering colleagues and short-hand commentary that suggest ways to adapt the care plan are not typically included in progress notes and are more accessible to covering providers when aggregated in a sign-out system.

While standalone sign-out systems such as manually updated word processor documents may improve workflow over paper processes, they can contain troublesome inaccuracies due to the significant effort required to transcribe and manually update information often available electronically. It is beneficial, therefore, to combine provider-entered clinical information with data automatically populated from the EMR.5, 22 Frank and colleagues at the Alfred I. DuPont Hospital for Children demonstrated that integration of a sign-out tool within the hospital’s EMR to automate the retrieval of demographic and clinical information improved efficiency and accuracy.19 In addition to utilizing data already present within the EMR, an EMR-integrated approach allows provider-entered sign-out information to be recorded in the EMR. Improved access to sign-out information has been shown to benefit communication by allowing the asynchronous transfer of information between members of the care team.23 Another potential benefit of EMR-integration is the development of automated checklists that provide clinical decision support using specific patient information to promote adherence to best practice guidelines or other protocols.

Customization for Neonatal Care

When an EMR-integrated sign-out tool adopted in the medical and surgical wards at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford failed to gain usage in the NICU,20 Palma et al. documented the development and acceptance of a sign-out tool specific to neonatal care (Figure 1, Figure 2).21 Following its introduction, the neonatal EMR-integrated sign-out tool was adopted rapidly, and provider satisfaction and perceptions of sign-out accuracy were improved compared to the NICU’s previous standalone sign-out tool, a Microsoft Access database.

Figure 1.

Neonatology team at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital using an EMR-integrated sign-out document to facilitate communication.

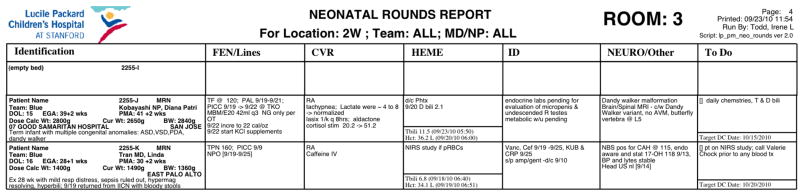

Figure 2.

Sample of an EMR-integrated neonatal sign-out document.

The experience at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital underscores the notion that the handoff process varies across different clinical settings.24 In order for an electronic tool to support communication in a particular setting, it must be tailored to the needs of that area. A primary reason that the EMR-integrated medical/surgical sign-out document was not adopted in the NICU was its length: each page of the printed document contained 2-3 patients, making the complete document cumbersome for rapid information retrieval in the 40-bed NICU. The neonatal sign-out tool was designed in such a way that each page includes up to 10 patients. Despite modification of the document’s layout, the representation of provider-entered sign-out information within the EMR is consistent with that of the medical/surgical sign-out. Because the information is patient-centric, when NICU patients are transferred to other units, their sign-out information automatically populates the sign-out document used in the receiving unit.

Electronic sign-out tools provide flexible layouts and alternative data views that permit powerful customization of the information contained in a sign-out document. The same system used throughout an institution can be adapted to fill the specialized needs of a neonatology service. In addition to standard demographic information, a neonatal sign-out tool should include an infant’s estimated gestational age. During the first several days following birth, it might also be useful to include the time of birth to aid in management decisions such as the treatment of hyperbilirubinemia. The birth weight should also be part of the sign-out document, as it is often used for medication dosing and fluid calculations during the first 1-2 weeks after birth. Laboratory data (e.g. total bilirubin levels) included on the sign-out could be annotated with the patient’s age in hours when clinically appropriate. At some point, perhaps at a week after birth, automating the calculation of postmenstrual age lends context to an infant’s clinical status. Whereas the medical data in sign-out systems are typically the patient’s own data, for the purposes of neonatal care, including key medical details about the mother may be useful.

Beyond Technology

Although this review focuses on technological approaches to improving communication, it is important to recognize that non-technical methods must be employed to address flawed handoff processes; computerization alone is not sufficient to improve communication in the setting of a poor process.5, 25 The process itself must be examined for communication failures, which define the steps required for improvement.24 Several manuscripts describe methodologies for refining the handoff process,26, 27 one of which evaluates handoffs in non-medical settings with high consequences for failure, such as nuclear power plants and the NASA Johnson Space Center.28 Only once the handoff process has been defined can a computerized tool be designed to support it effectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award 2 T32 HD007249. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Arora V, Johnson J, Lovinger D, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer DO. Communication failures in patient sign-out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streitenberger K, Breen-Reid K, Harris C. Handoffs in care: Can we make them safer? Ped Clin N Am. 2006;53(6) doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, Harrison BT, Newby L, Hamilton JD. The Quality in Australian Health Care Study. Med J Aust. 1995;163(9):458–471. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb124691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee S. A precarious exchange. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1822–1824. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Eaton EG, Horvath KD, Lober WB, Pellegrini CA. Organizing the transfer of patient care information: the development of a computerized resident sign-out system. Surgery. 2004;136(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray JE, Davis DA, Pursley DWM, Smallcomb JE, Geva A, Chawla NV. Network Analysis of Team Structure in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):e1460. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cull W, Mulvey H, Jewett E, Zalneraitis E, Allen C, Pan R. Pediatric residency duty hours before and after limitations. Pediatrics. 2006 doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang VY, Arora VM, Lev-Ari S, D’Arcy M, Keysar B. Interns Overestimate the Effectiveness of Their Hand-off Communication. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):491. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen LA, Brennan TA, O’Neil AC, Cook EF, Lee TH. Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Ann Intern Med. 1994 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-11-199412010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horwitz LI, Krumholz HM, Green ML, Huot SJ. Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(11):1173–1177. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.11.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Data - Root Causes by Event Type. [2011 April 16]; Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/Sentinel_Event_Statistics/

- 12.Kim GR, Lehmann CU. Technology CoCI. Pediatric aspects of inpatient health information technology systems. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1287–1296. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates DW, Gawande AA. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2526–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, Frankel RM. Lost in translation: challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2005;80(12):1094–1099. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilbridge P, Classen D. The informatics opportunities at the intersection of patient safety and clinical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(4):397–407. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Eaton EG, McDonough K, Lober WB, Johnson EA, Pellegrini CA, Horvath KD. Safety of using a computerized rounding and sign-out system to reduce resident duty hours. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1189–1195. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e0116f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flanagan ME, Patterson ES, Frankel RM, Doebbeling BN. Evaluation of a physician informatics tool to improve patient handoffs. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(4):509–515. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen LA, Orav EJ, Teich JM, O’Neil AC, Brennan TA. Using a computerized sign-out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24(2):77–87. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank G, Lawless ST, Steinberg TH. Improving physician communication through an automated, integrated sign-out system. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2005;19(4):68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein JA, Imler DL, Sharek PJ, Longhurst CA. Improved physician work flow after integrating sign-out notes into the electronic medical record. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(2):72–78. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palma JP, Sharek PJ, Longhurst CA. Impact of electronic medical record integration of a handoff tool on sign-out in a newborn intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2011;31(5):311–317. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarkar U, Carter JT, Omachi TA, Vidyarthi AR, Cucina R, Bokser S, et al. SynopSIS: integrating physician sign-out with the electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):336–342. doi: 10.1002/jhm.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidlow R, Katz-Sidlow RJ. Using a computerized sign-out system to improve physician-nurse communication. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(1):32–36. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Eaton E. Handoff improvement: we need to understand what we are trying to fix. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(2):51. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arora V, Johnson J. A model for building a standardized hand-off protocol. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(11):646–655. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams RG, Silverman R, Schwind C, Fortune JB, Sutyak J, Horvath KD, et al. Surgeon information transfer and communication: factors affecting quality and efficiency of inpatient care. Ann Surg. 2007;245(2):159–169. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000242709.28760.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patterson ES, Roth EM, Woods DD, Chow R, Gomes JO. Handoff strategies in settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care operations. Int J Qual Health C. 2004;16(2):125. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]