Abstract

Background

Prior efforts to examine the course of drinking from onset to midlife have been limited to analyses of year-to-year changes in alcohol dependence (AD). The current investigation sought to examine the course of drinking over this timeframe using consumption-based measures of drinking and evaluate the degree of comparability in trajectories estimated from diagnostic and quantity-frequency data.

Method

Participants included 420 men with a lifetime history of AD who were drawn from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry and administered the Lifetime Drinking History, which provided person-year (retrospective) data on patterns of consumption and diagnostic symptoms from drinking onset to participants’ current age. Consumption-based data were aggregated into age categories that ranged from “up to age 20” to “ages 54–56” and analyzed separately as a dichotomous measure of “heavy drinking (HD)” and continuous QFI scores.

Results

Using latent growth mixture modeling, trajectories based on the HD measure were moderately concordant with those based on changes in AD that were previously identified in this sample, whereas trajectories based on QFI scores were only weakly related to those based on AD diagnoses. Moreover, examination of the degree of concordance between AD- and QFI-derived trajectories revealed that measures of consumption (and potentially other continuous indices of drinking) may qualify past interpretations of various developmental trajectories that have been discussed in the alcoholism typology literature (particularly “Late Onset” alcoholism).

Conclusions

Collectively, the findings highlight the importance of integrating repeated measures of alcohol consumption in future efforts to describe the course of drinking across the lifespan.

Keywords: Diagnostic index, drinking course, midlife, Quantity-Frequency index

Introduction

Beginning with the seminal writings of Jellinek (1960) more than 50 years ago, researchers have focused on a variety of dimensions – including onset, gender, chronicity, severity, comorbidity, genetic underpinning, and drinking pattern – in an effort to identify more homogeneous alcoholism subgroups. Although subtype differences in developmental course have frequently been suggested, the growth of this literature was greatly influenced by Zucker’s (1994) evidence-based description of four alcoholism types differentiated on the basis of onset characteristics and developmental pattern. Since Zucker’s early writings (1979; Zucker and Gomberg, 1986), a number of empirical studies and theoretical models have become part of this burgeoning area of research. Contributing to this literature, the present study builds on our earlier analyses of problem drinking from onset to midlife with a particular interest in determining the degree of correspondence across trajectories based on three different drinking variables: a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (AD), a measure of heavy drinking (HD), and a continuous measure of consumption derived from reports of quantity and frequency of alcohol use. As described below, determining trajectory types that generalize across different drinking variables versus those that may be specific to a particular variable is of importance to theoretical, clinical and methodological interests.

Until recently, the extant literature regarding the developmental nature of alcoholism derived largely from two research literatures. First, epidemiological studies involving large representative samples have documented the prevalence and distribution of alcohol use across a number of demographic variables (e.g., socio-economic status, racial-ethnic characteristics, gender, age). Most relevant to issues of development, such studies have repeatedly found that alcohol use and alcohol-related problems typically begins during the adolescent years, peaks during the mid-twenties and then steadily decreases through subsequent life stages. Important limitations of this literature include reliance on cross-sectional data to describe the developmental nature of alcohol use and the limited emphasis on describing the onset and development of clinically significant alcohol problems (i.e., abuse and dependence) across the lifespan. A second literature has emphasized development and expression of abuse and dependence in the context of high-risk designs in which preadolescent and adolescent age samples have been extensively assessed and followed into their twenties.

Notably, a number of these studies employed longitudinal designs and frequently identified two distinct patterns in the course of alcohol use disorders: one characterized by chronic problem drinking that is associated with deviant behavior (referred as “antisocial alcoholism,” (Zucker, 1994)), the other by problem drinking that begins in late adolescence/early twenties and declines by the mid-twenties (referred to as “developmentally limited alcoholism,” Zucker, 1994). Few studies, however, have focused on the changing nature of alcohol use and abuse from drinking onset to middle age and late life [see Gee et al., (2007); Moos et al., (2005); Schutte et al., (2003)]. This is a notable omission from the literature, given elevated rates of treatment seeking in middle age and the importance of bridging drinking phases across the lifespan. Given the above considerations, several questions need to be addressed: (i) Do individuals who exhibit chronic alcoholism during their young adult years continue to do so into their thirties, forties and fifties? (ii) Do individuals who decrease consumption and problem drinking during their young adult years continue to show low levels of alcohol-related problems, or does problem drinking re-emerge later in life, and if so what characteristics distinguish those who do and do not return to problem drinking? (iii) Are there other alcoholism trajectories that only emerge in later life? (iv) Can we identify individual, interpersonal, and contextual variables that vary across different developmental trajectories?

Our research group has conducted three key studies relevant to these issues; two studies involved middle age veterans with a lifetime diagnosis of AD drawn from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry (VETR) (Eisen et al., 1987) and a third study assessed a non-twin sample of Vietnam veterans drawn from the Vietnam Era Study (VES) (Price et al., 2001) – a 25 year follow-up to the Vietnam Drug Users Return project (Robins, 1974) that assessed the long term medical and psychiatric consequences of substance abuse of veterans from the Vietnam. In each of these studies, longitudinal (retrospective) data, obtained from the Lifetime Drinking History (LDH) interview, were analyzed via Latent Growth Mixture Modeling (LGMM). Analyses of the first VETR sample identified four alcoholism trajectories, covering the period from drinking onset to 41 years of age (Jacob et al., 2005). Three of these patterns – Severe Chronic (SC), Young Adult (YA), and Late Onset (LO) – had clear counterparts in the larger typology literature (Zucker, 1994; Zucker et al., 2006), whereas a fourth alcoholism pattern – Severe Non-Chronic (SNC) – had not been described in the literature despite its seeming importance and considerable prevalence in the study. Analyses of the second (expanded) VETR sample, covering the period from drinking onset to 56 years of age, identified the same four AD trajectories (SC, SNC, YA, LO) providing evidence that these developmental types may be present into late midlife (Jacob et al., 2009), and clarified the nature of change and stability for these alcoholism trajectories over time. In our third study, we assessed the generalizability of our findings to a non-twin sample of middle age Vietnam Era veterans drawn from the VES (Price et al., 2001). LGMM analyses of a subsample of 293 veterans from this study with a lifetime diagnosis of AD also yielded a 4-class solution with trajectories that were parallel to those identified in our VETR-based samples (Jacob et al., 2010).

Notwithstanding the replicability and generalizability of these four trajectories, which are characterized by differences in the course of AD from drinking onset to midlife – our work thus far has been limited to analyses of year-to-year changes in AD diagnostic status among males with a lifetime history of AD. However, we have yet to examine whether other drinking measures would yield a similar set of trajectories; specifically, whether consumption-based measures, when examined in person-year form from drinking onset to midlife, would result in trajectories that parallel those obtained when AD diagnosis was the variable followed over time. The importance of obtaining such data is twofold. First, and most practically, there are relatively few longitudinal datasets that have assessed changes in AD from drinking onset to midlife. Several potentially relevant longitudinal datasets, however, have obtained measures of alcohol consumption over a considerable portion of the life-course (e.g., National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979; Center for Human Resource Research, 1994). To the extent that consumption-based measures yield similar patterns to those obtained with diagnostic measures, such datasets would afford an opportunity to conduct further studies on the course of alcoholism across samples with different characteristics than those found in our sample of middle-aged male veterans. Second, comparison of trajectories based on diagnostic-versus consumption-based measures can significantly enhance our understanding of differences in drinking trajectories over time. In particular, diagnostic-based trajectories – when interpreted within the context of concurrent patterns of alcohol consumption – may reveal incomplete (and possibly incorrect) characterizations of the patterns we are attempting to define. For example, with respect to the LO pattern, it is easy to assume that prior to the emergence of an AD diagnosis, individuals who fall within this trajectory engage in low rate, non-problem drinking and that the AD diagnosis first evident in the early- and mid-thirties is without precedent. This view is consistent with prior assertions that LO alcoholism may be triggered by significant environmental and/or physical stressors and/or onset of depression (Cloninger et al., 1996; Zucker et al., 2006); however, the course of this pattern of alcoholism based on consumption-based measures has not yet been identified. Similarly, for the YA trajectory, the rapid decline in diagnosable drinking behavior that occurs during the mid- to late-twenties does not necessarily mean that many of these individuals do not continue to engage in periods of moderate, or even heavy, drinking. Clearly, the meaning we give to differences in the developmental course of alcohol use could be different when based on diagnoses only versus diagnoses and ongoing consumption patterns.

The current study analyzes the same sample we used to identify trajectories based on year-to-year changes in the diagnosis of AD (Jacob et al., 2009). Three major hypotheses guided our analyses: (1) A measure of HD, based on quantity-frequency scores, would yield similar trajectories to those found with a diagnostic measure of AD, acknowledging that this expectation is based more on assumption than a supportive empirical literature, which is surprisingly small (Borges et al., 2010); (2) Continuous measures of alcohol consumption, based on quantity-frequency scores, would yield a more variable set of trajectories found with either the AD or HD measures; thus, reflecting “hidden” variability in course when finer grain indicators are analyzed; (3) Comparing trajectories based on HD or AD versus a continuous measure of alcohol consumption would reveal considerable variability in drinking pattern that is evident both prior and subsequent to periods of more problematic drinking associated with the HD and AD measures.

Method

Participants

All participants were originally a part of the VETR (Eisen et al., 1987; Henderson et al., 1990) and had been included in the Family Twin Study, which consisted of 1,295 male twins (Jacob et al., 2003). Out of this larger sample, 420 participants met diagnostic criteria for AD at some point in their lives, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and were selected for the current study. This was the same sample used in our previous studies (Jacob et al., 2005; 2009). Out of the 420 participants, there were 86 full twin pairs and 248 singletons (i.e., the co-twin did not have a lifetime AD diagnosis and, therefore, was not included in the sample). In our prior research, supplementary analyses using only one member of an intact twin pair yielded nearly identical findings to those observed in the full sample (see Jacob et al., 2005). Thus, all twins were analyzed as individuals in the current study. On average, participants were 50.4 years old at the time of assessment (SD = 2.80; range = 43–57) and had 13.4 years of education. The median income bracket was $50,001–$60,000, and 88.3% were employed at the time of assessment – for further details on this subsample of the VETR, see Jacob et al. (2009).

Procedure

The VETR involved the enrollment in 1987 of male twins who had both served in the military between May 1965 and August 1975, and who were asked to complete a mailed questionnaire. In 1992, a subset of the sample participated in a phone interview assessing for psychiatric disorders as part of the Harvard Drug Study (Tsuang et al., 1996). A subset of that sample was later assessed by self-report questionnaires and computer-assisted telephone interviews as part of the Family Twin Study (Jacob et al., 2003; Scherrer et al., 2004). All participants and data in the current study were drawn from the Family Twin Study.

Measures

Lifetime Drinking History

Alcohol-use variables, including lifetime diagnoses of AD, were gathered with the LDH (Skinner and Sheu, 1982), as modified by Jacob (1998), and administered in the Family Twin Study. Briefly, the LDH uses retrospective questioning to identify phases of drinking patterns across the lifetime. The first phase begins at the age when an individual started to drink regularly (i.e., at least one drink per month). The end of this phase and beginning of the next phase is defined by the participant as a significant change in the frequency or quantity of alcohol consumption. The interviewer directs the respondent to consider life changes and their associated drinking patterns to assist in their recall. In this study, participants were allowed to report up to 11 distinct drinking phases ending with their current age. On average, participants reported 4.1 phases (SD = 1.4) with an average phase length of 7.9 years (SD = 4.1).. The LDH has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid instrument for assessing drinking patterns over time (Gladsjo et al., 1992; Jacob et al., 2006; Koenig et al., 2009; Lemmens et al., 1997; Skinner and Schuller, 1982; Skinner and Sheu, 1982). For example, a test-retest study of retrospective reports of lifetime drinking patterns in which the LDH was administered 5 years apart indicated a high degree of correspondence in reports of age of first drink and quantity-frequency of drinking (rs > .6; Jacob et al., 2006; see also Koenig et al., 2009).

For each identified phase of drinking, the interview collected information regarding: (1) alcohol-related diagnoses, and (2) patterns of alcohol consumption. Diagnoses of AD for each drinking phase were made on the basis of having three or more DSM-IV dependence symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Patterns of consumption were based on a quantity measure (i.e., “During this phase of your drinking, how many drinks would you usually have on a day when you drank?”) and a frequency measure (i.e., “During this phase of your drinking, on how many days a month would you usually drink any alcoholic beverage?”). Multiplying the quantity and frequency scores provided a Quantity-Frequency Index (QFI), which reflected an individual’s average number of drinks per month during each drinking phase.

Other Lifetime Drinking History variables

In addition to diagnostic and quantity-frequency data, other drinking characteristics were determined: binge drinking (defined as drinking for 2 or more days without sobering up), morning drinking, drinking alone (at least half the time), and whether the participant had ever sought treatment for drinking problems. Participants were also asked to report on events that precipitated their first phase of AD, which they believe led to changes in their drinking pattern. Individuals could report on more than one of eight events that were related to school, work, family, relationships, peers, emotional problems, military service, or other factors (e.g., medical, legal, financial).

Household income

Participants selected their pre-tax household income from 19 categories, which were subsequently reduced to five income brackets: $30,000 and below (13.7%), $30,001–$50,000 (24.8%), $50,001–$60,000 (18.4%), $60,001–$80,000 (21.6%), and $80,000 and above (21.6%).

Other diagnoses

As part of the Harvard Drug Study, diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) were determined based on DSM-III-R criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1987); 7.1% of the current sample met criteria for this disorder).

Self-report questionnaires

A self-report questionnaire was used to assess variables related to drinking expectancies and personality. Since not all participants returned the questionnaire (82% response rate), information on these variables was not available for every participant for every scale. In our prior analyses with this sample we found no significant differences in the percentage of participants returning questionnaires as a function of AD class trajectory, or in terms of demographics or drinking characteristics by trajectory (see Jacob et al., 2009). Drinking expectancies were evaluated using the Comprehensive Effects of Alcohol (CEOA) scale, which has been found to be reliable and valid in the measurement of expected positive and negative effects of alcohol consumption (Fromme et al., 1993). A four-point scale was used to rate the following drinking expectancies: risk and aggression, tension reduction, liquid courage, and cognitive and behavioral impairment. All CEOA scales had two items, except for risk and aggression, which was comprised of three items. The sample size for all scales ranged from 330 to 332. In the larger Family Twin Study sample (n = 770), alpha coefficients (α) for the CEOA scales ranged from .60 (sociability) to .85 (sexuality).

The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (McCrae, 1999; McCrae and John, 1992) was used to assess traits of extraversion, openness, neuroticism, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (n = 332–333), with 12 items per scale. The Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (Tellegen, 1982) was used to assess traits of aggression and control with 10 and 9 items, respectively (n = 330). The MPQ and the NEO personality inventories have both demonstrated excellent reliability and validity (McCrae, 1999; McCrae and John, 1992; Tellegen, 1982). In the full sample from the Family Twin Study, coefficient alphas for these NEO and the MPQ scales ranged from .64 (openness) to .84 (neuroticism).

Analyses

Data Preparation

Using the age of onset at each phase, data on AD and QFI scores from the LDH were converted to a “person-year” structure for each participant. Specifically, for each phase that was reported, all years that were part of that phase were given the same designation. For example, if an individual reported his first phase as occurring from ages 18 to 21, and reported that he met criteria for AD during that time, an AD diagnosis was designated as occurring for ages 18, 19, 20, and 21. Thus, the resulting person-year files comprised data for each year from the age when an individual started to drink regularly (i.e., at least one drink per month) until their current age. As in our previous studies (Jacob et al., 2009; Jacob et al., 2005), we then collapsed the person-year data for AD and QFI into 13 distinct age categories to facilitate estimation of latent trajectories (up to age 20, ages 21–23, 24–26, 27–29, 30–32, 33–35, 36–38, 39–41, 42–44, 45–47, 48–50, 51–53, and 54–56). All age groups contained some missing data due to variability in both the age of participants, as well as the age at which they first started drinking. For example, in the last two age categories, the percentage of participants with missing data increased substantially (45.5% for ages 51–53, n = 191; 90.2% for ages 54–56, n = 379).

For the current study, QFI scores were analyzed both as a dichotomous and a continuous variable. Regarding the former, scores were dichotomized into “heavy drinking” (HD = QFI of 60 or more alcoholic drinks in a month) and “non-heavy drinking” and were calculated for each year from onset of regular drinking until the participant’s current age. Of the total sample of 420 individuals with lifetime AD, 82.1% (n = 345) met this definition of HD at some point in their lifetime. Although our threshold for HD, which is equivalent to at least two drinks per day, on average, is slightly lower than some HD definitions in the literature (e.g., Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Department of Health and Human Services, 2010), use of a more stringent cutoff significantly reduced the number of cases in the AD sample that could be included in the analyses of HD. For example, out of the 420 individuals with AD, only 74.8% (n = 314) reported a QFI of 75+ (average of at least 2.5 drinks per day) during a phase in their lifetime, and only 69.0% (n = 290) reported a QFI of 90+ (average of at least 3 drinks per day). To maximize the comparability in sample sizes for AD and HD analyses, we chose a more liberal threshold in defining HD in this study. Notably, the shape and number of the latent trajectories obtained using this definition of HD were essentially identical when based on (a) QFI scores of 75+ or 90+, and (b) when requiring respondents to have reported both a QFI of 60+ and an average of five or more drinks per drinking occasion during at least one drinking phase in their lifetime (Stahre et al., 2006).

In preparation for a continuous QFI measure, we inspected the distributions of raw scores on this index and found these variables to be heavily (positively) skewed. To address this issue, we examined the distribution of QFI scores across all ages in the dataset and assigned a percentile rank to each score based on where it fell in the total distribution of scores across all ages. Transformation of the raw QFI scores based on this rank normalization was conducted with a macro that is publicly available on-line (Wessa, 2008).

Latent Growth Mixture Modeling

As in our previous analyses of AD trajectories, we used LGMM (Muthén and Shedden, 1999) to examine the course of alcohol consumption over time as measured by QFI scores. This statistical approach, designed for the analysis of longitudinal data, represents an extension of finite mixture modeling (Mclachlan and Peel, 2000) and attempts to identify common patterns of growth (latent trajectories) based on measurement of a given variable over multiple time points. Within each trajectory, individual trajectories are identified via estimated means associated with latent intercept and slope factors for that trajectory. Means of these two latent factors are allowed to differ across latent trajectory groups. In contrast to latent class growth models (Nagin and Tremblay, 1999), LGMMs allow for modeling of the variability on the latent intercept and slope factors within each trajectory group in the form of random (as opposed to fixed) effects.

LGMM models for both the dichotomous (i.e., HD) and continuous QFI data were fit for one through five latent groups using Mplus Version 5.2 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2008). Procedures for modeling the course of the categorical HD data were consistent with our previous LGMM analyses of AD trajectories in this sample. Specifically, estimation of the degree of risk for HD was evaluated by specifying probit thresholds that were set to be equal across the age categories, with linear slope values (which estimated growth over time) set to the midpoint of each age category, and model estimation based on the maximum likelihood ratio estimator. Adjudication of the “best-fitting” model was based on review of the following fit indices: Akaike Information Criterion (AIC = −2LL + 2r), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC = −2LL + r*ln (n), and sample-size adjusted BIC = −2LL + r*ln ((n + 2)/24); LL = likelihood function, r = number of free parameters, n = sample size. Given that model selection based solely on these fit indices may yield more classes than necessary to explain the data, we utilized the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin test to assess the relative improvement in fit with successive increases in the number of classes. In addition, entropy was used to evaluate the quality of classification with values greater than .80 interpreted as “good” delineation among the identified classes in a model (Celeux and Soromenho, 1996). Finally, practical consideration was given to the size of classes such that classes were rejected if they included a small number of participants that would be less likely to replicate in future analyses (e.g., < 5% of the sample).

For modeling the course of QFI as a continuous variable, we tested a Free Curve Slope Intercept (FCSI) mixture model as presented by Wood (in press). Under the free curve mixture model, minimal structure on the course of drinking over time is assumed; although the variance of the slope latent variable is fixed to 1 for identification purposes, all loadings associated with slope over time are free to vary. In contrast to polynomial curve models, the FCSI mixture model entails no parametric assumptions about the form of growth in a variable over time. Some have suggested that FCSI models are preferable to quadratic models for growth curve data, given that polynomial curves do not replicate the asymptotic plateaus often present in developmental data (Browne, 1993; Ram and Grimm, 2007), and successively higher powers of polynomial effects are required to estimate non-linear patterns of growth than FCSI models. For the present analyses, an orthogonal form of the FCSI was estimated in which the covariance between the slope and intercept factors is fixed at zero (Meredith and Tisak, 1990). The mean and variance of the intercept variable were freely estimated as well. In addition, error variances for the manifest variables were freely estimated across measurement occasions but fixed to equality across the mixture groups for identification reasons. Intercepts of manifest variables were fixed to zero. To minimize the effect of missing data patterns and cohort confounds (Hipp and Bauer, 2006), the number of starts was increased to 30,000 with second stage optimizations increased to 30. The analyses were also run employing several different start values as a further assurance that the solution reported here does not represent a local minimum of the mixture model loss function.

Analyses based on class membership

Results from the LGMMs yield several estimates of class characteristics including “class membership probabilities.” These probabilities were used to assign individuals to a latent trajectory group based on their highest probability of class membership, and was conducted separately for the LGMM analyses of dichotomous (i.e., HD) and continuous QFI scores. Following these classifications, we conducted cross-tabulations (separately for the dichotomous and continuous QFI variables) to examine concordance in classification of drinking course with the AD trajectories previously identified in this sample (Jacob et al., 2009).

To assess the degree to which diagnostic and QFI measures are similarly related to external covariates, we conducted general linear models (for continuous variables) and likelihood ratio chi-square analyses (for dichotomous variables) to determine whether significant differences existed between the latent trajectory QFI groups on these variables. General linear model analyses were run in SASTM1 (Ninth Edition; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) using least squares (LS) mean contrasts, with p-values for the pairwise LS means comparisons adjusted via the Tukey method. As an additional check, these models were also run in SAS using the PROC MIXED procedure (Littell et al., 1996) to correct for the dependent nature of the data (i.e., some twins pairs were included in the data). However, the pattern of significant results was unchanged; thus, the original, uncorrected results are presented. Chi-square tests (Likelihood Ratio) from cross-tabulations were run in SPSS. Post-hoc logistic regressions were conducted for significant categorical covariates by regressing the covariate separately onto dummy-coded variables for the individual class designations. For all analyses, effects with p < .05 were interpreted as significant; however, it must be noted that the Type I error rate may be increased when conducting a large number of comparisons to test a single null hypothesis (see Greenland and Rothman, 1988).

Results

Pattern of Alcohol Consumption over Time for Total Sample

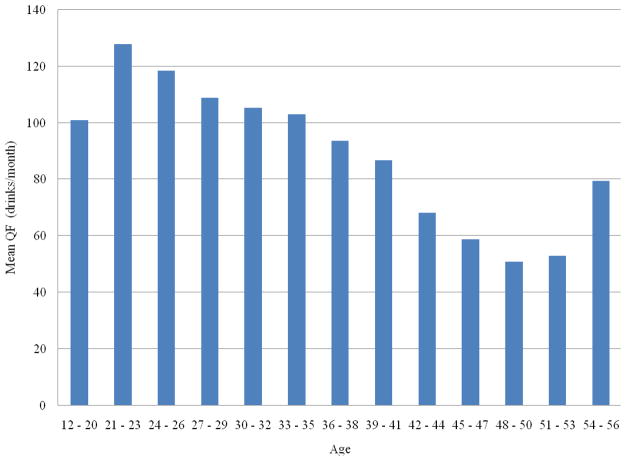

Figure 1 depicts the mean QFI scores across the 13 age categories for the total sample of AD men. Consistent with the general pattern of desistance in alcohol use as described in epidemiological studies (Muthén and Muthén, 2000), there was a peak in average QFI scores in early adulthood (ages 21–23) and a monotonic decline thereafter into the 50s. However, it should be noted that there was substantial variability in this mean QFI-derived pattern over time when plotted separately for each of the four AD trajectory groups previously identified in this data. (Data available from author upon request.)

Figure 1.

Mean QFI Scores by Age for Total Sample of Alcohol Dependent Men (n = 420).

Notes. QFI = Quantity-Frequency Index

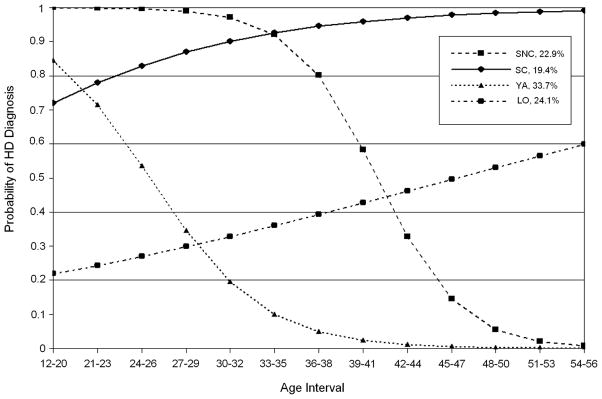

Latent Growth Mixture Models of Heavy Drinking among Individuals with Alcohol Dependence

A four-group solution was selected as the best fit for the HD trajectories, based on an examination of model fit (AIC = 3718.9, BIC = 3761.2, adjusted BIC = 3726.3), classification quality (entropy = .89), and the results of the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin tests, which indicated that a four-class solution was a significantly better fit than a three-class solution (LRT=229.9, p < .05). As seen in Figure 2, these four groups demonstrated similar trajectory patterns to those observed in our previous studies using diagnostic scores (Jacob et al., 2009; Jacob et al., 2005; Jacob et al., in press). The first class was defined as Severe Chronic (SC) heavy drinkers (n = 69, 20.0% of total HD sample), who were distinguished by relatively high probabilities of HD early in adulthood and continuing into the mid-50s. The second class consisted of Severe Non-Chronic (SNC) heavy drinkers (n = 78, 22.6%); here, the curve indicates a high probability of HD in early adulthood which declines sharply during the mid-30s and into midlife. The third, and largest, class resembled our previously identified group of Young Adult (YA) heavy drinkers (n = 116, 33.6%) and characterized by high probability of exhibiting HD in the early twenties and a rapid decline thereafter. The fourth class defined a pattern of Late Onset (LO) heavy drinkers (n = 82, 23.8%) who were characterized by low probabilities of HD in early adulthood and increasingly high probabilities of HD from young adulthood to midlife.

Figure 2.

Probability of Heavy Drinking among Individuals with Alcohol Dependence (n = 345)

Notes. HD = Heavy Drinking; SC = Severe Chronic, SNC = Severe Non-Chronic, YA = Young Adult, LO = Late Onset.

Comparison of Trajectory Group Designations by Alcohol Dependence and Heavy Drinking

Table 1 shows the results of a cross-tabulation analysis that examined the degree of concordance in classification for the HD trajectories with the AD trajectories previously identified in this sample (Jacob et al., 2009). The counts and percentages in Table 1 refer to the distribution of individuals within each AD trajectory group who were classified into each of the HD trajectory groups. Cohen’s (1960) kappa for this distribution was .51, which indicates a moderate level of agreement per Fleiss (1971). As observed from the diagonal values, the majority of individuals in the AD trajectories of SC, SNC, and YA were classified within the corresponding trajectories based on HD. The lowest degree of concordance (50% of cases) was observed for those classified within the LO group based on AD. Notably, the remaining half of these cases were classified primarily into the HD trajectories of SC and SNC (see Table 1); thus, the vast majority of cases classified as LO based on the HD index likely exhibited high levels of drinking prior to their first diagnosis of AD.

Table 1.

Cross-tabulation of Trajectory Group Designations for Alcohol Dependence and Heavy Drinking Criteria.

| HD Class | AD Class

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Chronic | Severe Non-chronic | Young Adult | Late Onset | Total | |

| Severe Chronic | 35 71.4% |

3 4.6% |

9 6.3% |

22 25.0% |

69 20.0% |

| Severe Non-Chronic | 7 14.3% |

40 61.5% |

14 9.8% |

17 19.3% |

78 22.6% |

| Young Adult | 5 10.2% |

3 4.6% |

103 72.0% |

5 5.7% |

116 33.6% |

| Late Onset | 2 4.1% |

19 29.2% |

17 11.9% |

44 50.0% |

82 23.8% |

| Total | 49 100% |

65 100% |

143 100% |

88 100% |

345 100% |

Notes. AD = Alcohol Dependence; HD = Heavy Drinking. Counts and percentages refer to distribution of HD classes within each AD class.

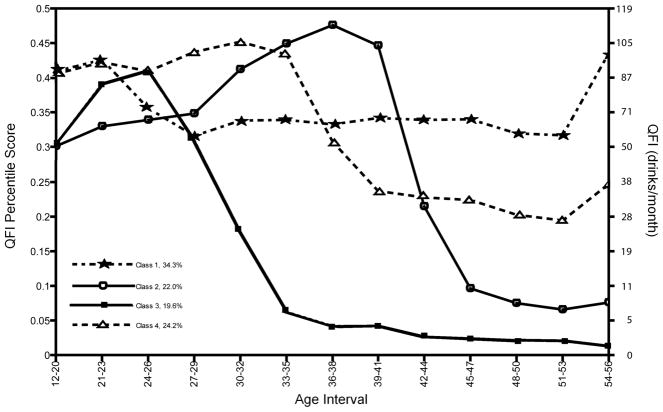

Latent Growth Mixture Models of QFI Percentile Scores among Individuals with Alcohol Dependence

A series of growth mixture models specifying one through five classes was fit to the QFI percentile scores using the FCSI model. Based on BIC fit statistics and the requirement that the obtained mixtures contain a sufficiently large number of individuals, the four group solution was selected as the best fit for the continuous QFI scores. Patterns over time for the free-curve trajectories are shown in Figure 3. Percentile rankings are presented on the Y-axis with corresponding raw QFI scores presented on the right-side of the figure to facilitate interpretation of the percentile scores, although it must be kept in mind that these raw QFI scores are only approximately equivalent to their percentile values. Class 1 (n = 153, 34.3% of total AD sample) represented the largest group and exhibited a relatively stable and moderate pattern of drinking across the age categories. Class 2 (n = 89, 22.0%) was characterized by a pattern of alcohol consumption that steadily increased through the 20s and 30s and then declined sharply to a very low level of drinking which remained low into the 50s. Class 3 (n = 91, 19.6%) peaked in their level of consumption in the mid-20s then decreased rapidly and maintained a very low level of drinking after the mid-30s. Class 4 (n = 87, 24.2%) initially exhibited somewhat higher levels of consumption, which remained stable until the mid-30s then declined and remained at a moderate level thereafter.

Figure 3.

Latent Trajectory Groups of Alcohol Consumption based on QFI Percentile Scores.

Comparison of Trajectory Designations by Alcohol Dependence and QFI Free-Curve

The results of a cross-tabulation comparing the trajectory designations for AD and for the QFI free-curve model are given in Table 2. As before, the counts and percentages in Table 2 refer to the distribution of individuals within each AD trajectory group that were classified into each of the four QFI free-curve trajectories. Cohen’s (1960) kappa for this distribution was .30, which indicates a poor level of agreement per Fleiss (1971). Among those classified as SC based on diagnoses of AD, most were classified into Class 1 based on the QFI free-curve model, which was characterized by a moderately high and stable level of drinking across the life-course. With regard to those in the SNC class for AD, the majority fell into Class 2 of the QFI free-curve model, which is marked by increasing patterns of alcohol consumption into the late 30s that drops precipitously thereafter. For YA alcoholics, as defined by AD diagnoses, most of these individuals fell into QFI free-curve Class 3 in which alcohol consumption peaks in the mid-20s then declines sharply thereafter and is minimal after the mid-30s. However, a sizeable proportion (34.9%) of cases from the YA class also fell into QFI free-curve Class 1. Finally, regarding the LO class, relatively comparable percentages of cases fell into QFI free-curve Classes 1, 2, and 4 (range of percentages: 28.2% – 35.9%).

Table 2.

Cross-tabulation of Trajectory Group Designations for Alcohol Dependence and QFI Free Curve Models.

| QFI Free Curve Class | AD Class

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Chronic | Severe Non-Chronic | Young Adult | Late Onset | Total | |

| 1 | 43 78.2% |

9 11.8% |

65 34.9% |

36 35.0% |

153 36.4% |

| 2 | 5 9.1% |

40 52.6% |

7 3.8% |

37 35.9% |

89 21.2% |

| 3 | 2 3.6% |

6 7.9% |

82 44.1% |

1 1.0% |

91 21.7% |

| 4 | 5 9.1% |

21 27.6% |

32 17.2% |

29 28.2% |

87 21.2% |

| Total | 55 100% |

76 100% |

186 100% |

103 100% |

420 100% |

Notes. AD = Alcohol Dependence; QFI = Quantity-Frequency Index. Counts and percentages refer to distribution of QFI Free Curve classes within each AD class.

Comparison of Class Characteristics for Alcohol Dependence, Heavy Drinking, and QFI Free-Curve Trajectories

Several covariates (i.e., demographic, other mental health diagnoses, antecedent events for first AD diagnosis, personality, and drinking and alcohol dependence variables) were analyzed in terms of significant differences across HD and QFI free-curve classes. F and χ2 statistics, significance levels, and the means/prevalances by class designation for HD are given in Table 3 and presented alongside results based on comparisons of class characteristics previously reported for AD (Jacob et al., 2009). F and χ2 statistics, significance levels, and the means/prevalances by class designation for the QFI free-curve classes are presented separately in Table 4. Across these two tables, results are presented only for variables that were significant for at least one of the class designations (i.e., AD, HD, or QFI free-curve). Specifically, in our previous analyses with this sample (Jacob et al., 2009), AD-based trajectories were not differentiated in terms of the following: demographics (age at interview, employed at assessment; other mental disorder diagnoses (nicotine dependence, any drug dependence, major depression); antecedent events for first AD diagnosis (school, family); NEO extraversion; religion/spirituality indices; drinking characteristics (either father/mother excessive drinker, ever binge drinking; drinking expectancies (self-perception, sociability, sexuality). Similarly, none of these covariates differentiated the HD- or the QFI free-curve trajectories in the current analyses and are not included in these tables.

Table 3.

Significant covariates across class designations for Alcohol Dependence (AD) and heavy drinking (HD): Demographics, other mental disorder diagnoses, antecedent events for first AD diagnosis, personality variables, drinking characteristics, and drinking expectancies.

| Variable | Class Variable |

F or χ2 |

SC | Class designation | LO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | p | SNC | YA | ||||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Education, mean years | AD | 3.0 | .031 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 13.5 |

| HD | 0.7 | .539 | 13.1 | 13.2 | 13.4 | 13.4 | |

|

|

|||||||

| Household income (%) | AD | 21.3 | .046 | ||||

| %<30,000 | 26.0** | 16.0 | 9.0* | 14.0 | |||

| % >$80,001 | 8.0* | 25.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 | |||

| HD | 20.5 | .058 | |||||

| %<30,000 | 23.4 | 17.9 | 8.9 | 10.0 | |||

| % >$80,001 | 12.5 | 21.8 | 21.4 | 30.0 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Other mental disorder diagnoses | |||||||

| Antisocial personality (%) | AD | 19.0 | <.001 | 20.0*** | 11.8 | 3.2** | 3.9 |

| HD | 3.6 | .307 | 13.0 | 9.0 | 5.2 | 7.3 | |

|

| |||||||

| Antecedent events for first AD diagnosis (%) | |||||||

| Military | AD | 65.8 | <.001 | 54.5 | 60.5* | 62.4*** | 16.5*** |

| HD | 36.0 | <.001 | 42.0 | 55.1 | 69.0*** | 28.0*** | |

|

|

|||||||

| Relationship | AD | 46.1 | <.001 | 30.9 | 15.8** | 22.6** | 57.3*** |

| HD | 10.9 | .012 | 36.2 | 37.2 | 21.6** | 41.5 | |

|

|

|||||||

| Work | AD | 14.7 | .002 | 20.0 | 14.5 | 18.4 | 35.9*** |

| HD | 7.1 | .068 | 30.4 | 15.4 | 20.0 | 29.3 | |

|

|

|||||||

| Other | AD | 11.8 | .008 | 10.9 | 7.9 | 14.0 | 25.2*** |

| HD | 4.7 | .198 | 17.4 | 11.5 | 12.1 | 22.0 | |

|

|

|||||||

| Peer | AD | 8.8 | .031 | 63.6 | 61.8 | 60.2 | 44.7** |

| HD | 7.8 | .049 | 65.2 | 59.0 | 58.6 | 43.9** | |

|

|

|||||||

| Emotional | AD | 8.5 | .036 | 29.1 | 28.9 | 27.4 | 43.7** |

| HD | 4.8 | .184 | 31.9 | 39.7 | 25.9 | 36.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| Personality | |||||||

| NEO agreeableness | AD | 5.8 | <.001 | 40.3 a | 40.7 a | 43.5 b | 42.2 a,b |

| HD | 4.5 | .004 | 39.7 a | 42.0 a,b | 43.0 b | 42.5 b | |

|

|

|||||||

| NEO neuroticism | AD | 4.3 | .005 | 35.6 a | 34.0 a,b | 31.6 b | 31.5 b |

| HD | 1.8 | .141 | 34.6 | 31.7 | 31.9 | 32.4 | |

|

|

|||||||

| NEO conscientiousness | AD | 1.4 | .232 | 43.0 | 44.6 | 45.2 | 44.7 |

| HD | 3.6 | .014 | 42.8 a | 44.1 a,b | 45.3 a,b | 46.2 b | |

|

|

|||||||

| MPQ aggression | AD | 3.5 | .016 | 22.7 a,b | 23.4 a | 20.8 b | 21.5 a,b |

| HD | 2.1 | .105 | 23.4 | 21.8 | 21.0 | 21.7 | |

|

|

|||||||

| MPQ control | AD | 0.8 | .470 | 30.5 | 30.7 | 31.4 | 31.3 |

| HD | 4.4 | .005 | 29.5 a | 30.8 a,b | 31.4 b | 32.3 b | |

|

| |||||||

| Drinking Characteristics | |||||||

| Age of first drink | AD | 5.9 | <.001 | 14.6 a | 15.4 a | 15.7 a,b | 16.5 b |

| HD | 2.7 | .048 | 14.8 a | 15.4 a,b | 15.7 a,b | 16.1 b | |

|

|

|||||||

| Age of first AD diagnosis | AD | 214.6 | <.001 | 20.7 a,b | 20.0 a | 21.6 b | 33.2 c |

| HD | 21.9 | <.001 | 24.7 a | 23.5 a,b | 21.2 b | 28.4 c | |

|

|

|||||||

| Age of first AD or AB diagnosis | AD | 75.7 | <.001 | 20.1 a | 19.2 a | 20.5 a | 28.4 b |

| HD | 10.4 | <.001 | 23.0 a,c | 22.0 a,b | 20.0 b | 24.7 c | |

|

|

|||||||

| Age of first AD symptom | AD | 33.7 | <.001 | 18.9 a | 19.1 a | 19.5 a | 24.1 b |

| HD | 7.1 | <.001 | 20.3 a,b | 20.5 a,b | 19.1 b | 22.2 a | |

|

|

|||||||

| Ever sought treatment (%) | AD | 11.0 | .012 | 36.4 | 42.1* | 23.1* | 34.0 |

| HD | 25.4 | <.001 | 29.0 | 52.6*** | 19.8*** | 41.5 | |

|

|

|||||||

| Ever drinking alone (%) | AD | 13.4 | .004 | 52.7 | 60.5* | 38.2*** | 52.4 |

| HD | 25.8 | <.001 | 49.3 | 60.3* | 32.8*** | 65.9*** | |

|

|

|||||||

| Ever drink in morning (%) | AD | 4.9 | .180 | 7.3 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 6.8 |

| HD | 17.7 | <.001 | 15.9*** | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1.2 | |

|

| |||||||

| Drinking expectancies | |||||||

| Risk and aggression | AD | 3.1 | .027 | 8.0 a | 7.4 a,b | 7.3 a,b | 7.0 b |

| HD | 3.7 | .012 | 7.5 a,b,c | 7.6 a,b | 7.6 b | 6.7 c | |

|

|

|||||||

| Tension reduction | AD | 2.6 | .050 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.5 |

| HD | 3.1 | .029 | 5.4 a,b | 5.2 a,b | 5.0 a | 5.5 b | |

|

|

|||||||

| Liquid courage | AD | 2.2 | .084 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| HD | 3.7 | .013 | 5.0 a,b,c | 5.0 a,b | 5.1 a,b | 4.4 c | |

|

|

|||||||

| Cognitive and behavioral impairment | AD | 0.8 | .484 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| HD | 2.7 | .047 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 4.8 | |

Notes. For continuous variables, statistics sharing a common superscript in a given row are not significantly different from one another (p < .05), whereas statistics with different superscripts are significantly different. For categorical variables, significance levels are based on post-hoc logistic regressions in which the covariate was regressed separately onto dummy-coded variables for the individual class designations. Sample sizes for analyses were in the following ranges: AD severe chronic = 47–55, AD severe non-chronic = 57–76, AD young adult = 145–186, AD late onset = 80–103; HD severe chronic = 53–69, HD severe non-chronic = 63–78, HD young adult = 91–116, HD late onset = 120–153. Class Variables refer to trajectories based on either AD = alcohol dependence, HD = Heavy Drinking. AD and HD trajectory classes include: SC = Severe Chronic, SNC = Severe Non-chronic, YA = Young Adult, and LO = Late Onset. AB = alcohol abuse; MPQ = Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Table 4.

Significant covariates across class designations for QFI Free-Curve trajectories: Demographics, other mental disorder diagnoses, antecedent events for first AD diagnosis, personality variables, drinking characteristics, and drinking expectancies.

| Variable |

F or χ2 |

QFI Free-Curve Class designation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | p | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Education, mean years | 0.2 | .876 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 13.4 | 13.3 |

|

|

||||||

| Household income (%) | 19.8 | .071 | ||||

| %<30,000 | 15.1 | 14.8 | 8.0 | 16.3 | ||

| % >$80,001 | 14.4 | 22.7 | 29.5 | 24.4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Other mental disorder diagnoses | ||||||

| Antisocial personality (%) | 5.2 | .161 | 12.2 | 6.8 | 4.1 | 5.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Antecedent events for first AD diagnosis (%) | ||||||

| Military | 8.8 | .032 | 52.3 | 38.2* | 59.3* | 47.1 |

|

|

||||||

| Relationship | 14.8 | .002 | 24.8* | 34.8 | 23.1 | 46.0*** |

|

|

||||||

| Work | 1.4 | .704 | 24.3 | 18.0 | 23.1 | 21.8 |

|

|

||||||

| Other | 0.9 | .815 | 13.7 | 14.6 | 15.4 | 18.4 |

|

|

||||||

| Peer | 5.7 | .129 | 63.4 | 53.9 | 58.2 | 48.3 |

|

|

||||||

| Emotional | 4.7 | .196 | 28.8 | 36.0 | 26.4 | 39.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Personality | ||||||

| NEO agreeableness | 5.7 | <.001 | 41.0 a | 41.4 a,b | 43.3 b,c | 44.0 c |

|

|

||||||

| NEO neuroticism | 2.2 | .089 | 33.6 | 33.2 | 31.3 | 31.3 |

|

|

||||||

| NEO conscientiousness | 1.4 | .230 | 44.1 | 44.4 | 45.9 | 44.6 |

|

|

||||||

| MPQ aggression | 1.1 | .342 | 22.2 | 22.1 | 21.0 | 21.2 |

|

|

||||||

| MPQ control | 0.5 | .688 | 31.1 | 30.8 | 31.6 | 31.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Drinking Characteristics | ||||||

| Age of first drink | 1.7 | .168 | 15.3 | 15.9 | 16.1 | 15.7 |

|

|

||||||

| Age of first AD diagnosis | 11.8 | <.001 | 23.0 a | 26.2 b | 21.7 a | 26.1 b |

|

|

||||||

| Age of first AD or AB diagnosis | 4.2 | .006 | 21.7 a,b | 23.0 a,b | 20.8 a | 23.6 b |

|

|

||||||

| Age of first AD symptoms | 2.7 | .043 | 20.1 | 21.0 | 19.8 | 21.5 |

|

|

||||||

| Ever sought treatment (%) | 16.2 | <.001 | 24.8* | 40.4* | 20.9* | 42.5** |

|

|

||||||

| Ever drinking alone (%) | 14.2 | .003 | 48.4 | 51.7 | 31.9** | 58.6* |

|

|

||||||

| Ever drink in morning (%) | 8.2 | .042 | 7.8** | 1.1 | 2.2 | 3.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Drinking expectancies | ||||||

| Risk and aggression | 0.5 | .702 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 7.1 |

|

|

||||||

| Tension reduction | 1.9 | .125 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.4 |

|

|

||||||

| Liquid courage | 0.5 | .661 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.7 |

|

|

||||||

| Cognitive/Behavioral impairment | 0.2 | .865 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.7 |

Notes. For continuous variables, statistics sharing a common superscript in a given row are not significantly different from one another (p < .05), whereas statistics with different superscripts are significantly different. For categorical variables, significance levels are based on post-hoc logistic regressions in which the covariate was regressed separately onto dummy-coded variables for the individual QFI free-curve class designations. Sample sizes for analyses were in the following ranges: QFI Free-Curve Class 1 = 120–153, Class 2 = 68–69, Class 3 = 71–91, Class 4 = 66–87. AD = alcohol dependence; AB = alcohol abuse; MPQ = Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Regarding demographics, in contrast to the AD classes, there were no significant differences across either the HD or QFI free-curve classes in terms of years of education or household income. Moreover, in contrast to the AD classes, the HD and QFI free-curve classes did not differ in terms of percentage of individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of ASPD. However, in terms of antecedent events for first AD diagnosis, for class designations based on either AD or HD, YAs were primarily linked to military events, LOs were primarily linked to relationship events, and SCs were primarily linked to peers. For the QFI free-curve classes, Class 3 was primarily linked to military events, whereas Class 4 was primarily linked to relationship events. With respect to differences in personality, for both AD and HD, SCs were lowest on agreeableness, as was Class 1 from the QFI free-curve model. Based on HD, SCs were lowest on conscientiousness and control.

Regarding differences in drinking characteristics, for both AD and HD class designations, LOs had the oldest age of first drink, AD diagnosis, AD or alcohol abuse (AB) diagnosis, and AD symptom. In terms of the QFI free-curve classes, those in Classes 2 and 4 had the oldest age of first AD diagnosis, AD or AB diagnosis, and AD symptom. Across both AD and HD class designations, SNCs were mostly likely to seek treatment, as were those from QFI free-curve Class 4. Rates of drinking alone were highest for SNCs (based on AD class designations), LOs (based on HD class designations), and those in QFI free-curve Class 4. Rates of drinking in the morning were highest for SCs (based on HD class designations) and those in QFI free-curve Class 1. In terms of drinking expectancies, for both AD and HD, those classified as LOs had the highest expectancies that alcohol would reduce tension. However, in terms of expectancies that alcohol would prompt them to become more risky and aggressive, the highest levels were observed for SCs when based on AD class designations and YAs and LOs when based on HD class designations.

Discussion

The developmental nature of alcoholism has attracted increasing research interest during the past several decades in an effort to characterize differences in the course of alcoholism over the lifespan. Our previous work has provided empirical support for several, often described alcoholism types having different developmental features (i.e., SC, YA, LO, and SNC alcoholism). The aim of the current study was to conduct parallel analyses based on alcohol consumption versus diagnostic measures, and in so doing, to assess the comparability of trajectories derived with different measures, and to determine the value of considering changes in consumption when interpreting trajectories based on diagnostic measures. Major findings indicated that (1) trajectories based on a dichotomous measure of HD were similar to (but not identical with) those based on changes in AD diagnoses over time; (2) trajectories based on a continuous measure of alcohol consumption (QFI) were only weakly related to those based on AD diagnoses, (3) examining the nature of non-concordance between AD- versus QFI-derived trajectories added new meaning and qualification to our earlier description of AD-derived trajectories.

Concordance between Trajectories Derived from Measures of Alcohol Dependence and Heavy Drinking

We anticipated that an HD measure would yield similar trajectories to those obtained from our diagnostic measure, an expectation that was partially confirmed. As seen in Table 1, there was moderate concordance in classification of individuals into the same group based on the HD- versus AD-derived trajectories. The LO group, however, exhibited a lower degree of concordance, a finding that will be returned to in a subsequent section.

For some, these associations between HD and AD measures support the perspective that drinking, problem drinking, and dependent drinking are points along a continuum of severity, which is reflected in the degree of behavioral or physical impairment (as indexed by number of symptoms) and/or by amount of alcohol consumed as indexed by QFI-derived measures (Borges et al., 2010; Bucholz et al., 1996). From this perspective, which is often an underlying assumption of population-based studies from the field of epidemiology, there is nothing uniquely or qualitatively different about the point along this continuum where a diagnosis is assigned compared with a point where less than all diagnostic criteria are met.

Notwithstanding the moderate level of agreement between HD and AD measures with regard to trajectory assignment, there were areas of non-concordance, which qualify how one interprets the observed similarities between AD- and HD-derived trajectories. First, in the original sample of 420 participants with a lifetime diagnosis of AD, approximately 18% (n = 75) did not have a period of time in which they consumed 60+ drinks per month (i.e., our dichotomized index of HD). [Given that our interest was in clustering HD individuals into different developmental trajectories and comparing the obtained trajectories with those derived from an AD measure, our analyses required each case to exhibit a lifetime history of both AD and HD.] The most likely explanation for this finding is that AD cases without a history of HD (referred to as AD/HD−) are less severely affected individuals representing the “lower end” of an AD phenotype. Consistent with this explanation, findings indicated significant group differences (with the AD/HD− group exhibiting less severity than the AD/HD+ group) in regard to (1) number of AD criteria endorsed, (2) prevalence of ASPD, drinking alone, binge drinking, and having obtained treatment, and (3) number of years during which AD was exhibited. Furthermore, a greater proportion of the AD/HD− group vs. the AD/HD+ group was classified into the YA trajectory and a smaller proportion into the SC trajectory. Clearly, a lifetime diagnosis of AD is characterized by considerable heterogeneity, in which some individuals can exhibit one or more episodes of AD without consuming a very large volume of alcohol. As will be recalled, the VETR (from which our cases were drawn) is population-based, and as such, most likely includes a larger proportion of the less severely affected AD/HD− cases than would be found a sample drawn from a treatment population. Alternatively, the fact that registry participants were drawn from the ranks of the military may have excluded some of the more severe AD/HD+ cases.

Second, the association between covariates and the emergent trajectories differed when analyses used AD versus HD measures; most importantly, variables related to undercontrol and severity (i.e., ASPD, NEO neuroticism, MPQ aggression) more clearly differentiated trajectories based on the AD versus HD measure – a difference which is probably related to the diluting effect resulting from classification discordance. For example, 30% of the SC cases, based on the AD measure, were classified into a different trajectory when based on the HD measure (14% as SNC, 10% as YA, and 4% as LO). To the extent that the SC group reflected severity and chronicity when based on the AD measure, any changes from this composition would decrease the severity/chronicity distinction of this trajectory.

Concordance between Trajectories Derived from Measures of Alcohol Dependence and Continuous QFI Scores

When analyses were based on a continuous measure of alcohol consumption, similarity with the AD-based trajectories was poor (see Figure 3). For example, the “shape” of Class 2 was most similar to the SNC trajectory (based on AD) and was characterized by an increasingly high consumption rate from the early twenties to the mid-thirties at which point consumption levels declined and remained at a low level thereafter (i.e., an average of 10 or less drinks per month by the mid-forties). Yet, concordance between the SNC group and Class 2 was only 53%, and the SNC group had substantial overlap with other QFI-based trajectories. The shape of Class 3 was most similar to the AD-based YA group (i.e., high levels of consumption during the twenties, which declined to an average of 5 or fewer drinks per month during the late thirties); however, the level of concordance (44%) was quite modest. Further, the AD-based LO group yielded concordance rates with Class 1 (35%), Class 2 (36%) and Class 4 (28%). Notably, only the AD-based SC trajectory exhibited a substantial degree of concordance (78%) with one of the QFI-based groups (Class 1), which is characterized by a peak drinking volume during the mid-twenties (approximately 85 drinks per month) followed by a decline to a substantial, though not extreme, drinking level (approximately 50 drinks per month) and remaining at that level thereafter. Despite this overlap between SC and Class 1, 55 of the 420 AD-based cases (13% of the total) were classified as SC, whereas 153 of the 420 QFI-based cases (36% of the total) were classified as Class 1; thus, many more cases were classified into the Class 1 trajectory than the SC trajectory. Significant differences in proportion of cases classified by AD-versus QFI-derived trajectories were also evident with the AD-based YA group which comprised 44% of the total sample in contrast with Class 3, which comprised 21% of the total sample.

As seen in Table 3, there was very little differentiation among QFI-derived trajectories regarding associations with covariates in contrast with AD- and HD-derived groups. Only nine covariates differentiated trajectories based on the continuous QFI scores, whereas 17 and 20 covariates differentiated trajectories based on HD and AD, respectively. Moreover, no covariates differentiated trajectories only when based on the continuous QFI scores, and (as was true with the HD-derived groups) undercontrol and severity covariates (i.e., ASPD, NEO neuroticism, MPQ aggression) were not different across the QFI-derived trajectories.

Several conclusions can be drawn from these results. First, QFI-derived trajectories may not be suitable “proxies” for the AD-based trajectories. Second, for those with a lifetime diagnosis of AD, the pattern of consumption over time reflects substantial variability resulting in limited correspondence between change in consumption and change in status of AD. Third, it appears that consumption-based trajectories may qualify how we have interpreted the different developmental trajectories that have been discussed in the alcoholism typology literature. A few such qualifications are suggested in the current findings.

Integrating Alcohol Consumption Data with Trajectories based on Diagnostic Measures

When we first described the SC, SNC, YA and LO trajectories, the person-year data were based on the presence/absence of an AD diagnosis during each year from drinking onset to current age. Other year-to-year data such as HD or QFI scores were not incorporated into our interpretations of the various patterns. Consequently, we no doubt presented a “cleaner” picture of the different trajectories than would have emerged if ongoing changes in consumption were considered. Specifically, current analyses indicate considerable variation in alcohol consumption even when drinking-related symptomatology does not achieve diagnostic levels. Although this is not particularly newsworthy in a general discussion of alcoholism, it is an important issue that is often forgotten when describing different alcoholism trajectories and how these trajectories vary with regard to individual, interpersonal and contextual correlates. For example, the LO trajectory – referred to by Zucker as negative affect alcoholism – is often described as more common among women and/or related to affective symptomatology or to the onset of significant life stressors (Fillmore et al., 1979; Zucker and Gomberg, 1986; Zucker et al., 2006). For individuals in the LO trajectory (based on the presence/absence of an AD diagnosis), the probability of achieving this diagnosis is very low during the twenties, but increases during the mid to late thirties (Jacob et al., 2005; Jacob et al., 2009). When viewed in this manner, it is easy to assume that this delayed onset of AD is preceded by a history of minimal or moderate drinking. However, examination of the consumption patterns of these individuals indicates that many drank heavily prior to their thirties. Specifically, of the 103 individuals in the present sample that were classified as LO based on diagnoses of AD, only 9 abstained from drinking prior to their thirties; whereas 41 (approximately 40%) exhibited HD (i.e., QFI> 60/month) prior to their thirties and engaged in HD for an average of 7.8 years between drinking onset and thirty years of age. This LO trajectory is clearly different from the characterization of LO alcoholism as a drinking class marked by minimal alcohol consumption prior to the onset of AD. Consistent with this finding, Sacco, Bucholz, and Spitznagel (2009), making use of an epidemiological sample (Grant et al., 2003) reported a class of drinkers who exhibit a high likelihood of heavy drinking but a low likelihood of exhibiting symptoms of alcohol abuse and dependence.

Another trajectory reflecting notable variability in consumption is the YA pattern, where in the aggregate (see Figure 1), it appears that drinking normalizes quickly (QFI=30 of fewer drinks per month) after having achieved an AD diagnosis in their late adolescence/early twenties. Incorporating the QFI data, however, indicates that a sizeable number of YA cases exhibit periods of HD after transitioning to non-HD drinking in their late twenties; specifically, 36% of the YAs cases exhibited HD for an average of 6.3 years after age 30.

Limitations

In interpreting current results, several potential limitations should be considered. First, our sample included males only; thus it is unclear whether the identified trajectories based on AD, HD, and continuous QFI scores are descriptive of the course of alcohol use among women. It must be recognized, however, that it is difficult to obtain longitudinal data involving females with a lifetime diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder that are not limited to relatively short time frames (Borges et al., 2010; Edens et al., 2007). Second, questions might be raised regarding the reliability and validity of our retrospective LDH measure. Although there are now various studies that demonstrate the psychometric adequacy of the LDH (e.g., Jacob et al., (2006) and Koenig et al., (2009), we do believe that prospective data are still the “gold standard.” Several ongoing prospective studies, which are following participants into the fourth decade of life, will provide an opportunity to determine the generalizability of the present findings over this portion of the life-course (e.g., Sher et al., (1991). Third, our dataset did not include finer-grained (repeated) measures of individual, interpersonal and contextual variables that have been hypothesized to influence the course of alcoholism. To address this issue, our next assessment of this sample will include additional measures to better define these domains. Fourth, our use of a quantity-frequency index as the main dependent variable and definition of HD (QFI ≥ 60) did not allow us to distinguish between frequent patterns of low-risk drinking from less frequent patterns of high-risk drinking. Nevertheless, when comparing our current definition of HD with a more stringent definition – i.e., QFI ≥ 60 and drinking an average of 5 drinks per drinking occasion – there was a 90% concordance rate for lifetime HD (n=309), and an average concordance rate of 81% when examining the correspondence between these HD definitions within each of the 13 age categories used in our analyses. Thus, our use of QFI and definition of HD in the current study appeared to be fairly successful at capturing “at-risk” drinking. Fifth, given that one variable is binary and the other continuous, it is conceivable that differences between the AD (or HD) and QFI free-curve trajectories may be attributable, in part, to differences in analytic methods, an issue that merits further study. Nevertheless, we believe that such differences are also clearly substantive, given the consumption patterns for the AD-based trajectories that were described above (i.e., LOs, YAs). Sixth, given the considerable amount of missing data from the age categories of 51–53 and 54–56, some caution is warranted when interpreting drinking trajectories in these age ranges.

Conclusions

Two findings from the current study are of particular importance. First, consumption based measures that distinguish excessive drinking from social/moderate drinking yield trajectories that are quite similar to those based on diagnostic levels of drinking. Yet, the differences in trajectories based on these two types of measures are as important as their similarities. Specifically a substantial proportion of individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of AD (about 20% of our sample) report never having engaged in some period of excessive drinking (QFI>60 drinks per month), a subset that includes a significant number of individuals who satisfy DSM-IV criteria for AD but often do so at a lower level of severity. Given the limited empirical literature that has actually examined the relationship between consumption and diagnostic measures, present findings are notable and can provide a point of comparison with future studies based on different samples. Second, the use of a continuous consumption measure provided data that require us to re-evaluate how we have interpreted trajectories based on diagnostic measures. Specifically, examination of variations in QFI scores as related to the AD-based trajectories serves to remind us that seemingly low probabilities of exhibiting an AD diagnosis do not necessarily mean that low levels of drinking are occurring during that time. Within the LO trajectory, a sizeable proportion of cases are engaging in heavy drinking when there is a low probability of exhibiting an AD diagnosis (< 30 years of age) and within the YA trajectory, a sizeable number of cases are engaging in heavy drinking after diagnosable AD is of low probability (>30 years of age). Such findings appear consistent with a continuous model of alcohol use, abuse and dependence where a transition from heavy drinking to diagnosable drinking would be the norm and not the exception.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Veterans Administration Merit Award and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant (R01-AA016402) awarded to Theodore Jacob.

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs has provided financial support for the development and maintenance of the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry. Numerous organizations have provided invaluable assistance, including: VA Cooperative Study Program; Department of Defense; National Personnel Records Center, National Archives and Records Administration; the Internal Revenue Service; National Institutes of Health; National Opinion Research Center; National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences; the Institute for Survey Research, Temple University. Most importantly, the authors gratefully acknowledge the continued cooperation and participation of the members of the VET Registry and their families. Without their contribution this research would not have been possible.

Footnotes

SAS is a registered trademark of SAS Institute, Cary, NC.

Contributor Information

Theodore Jacob, Family Research Center, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System

Daniel M. Blonigen, Center for Health Care Evaluation, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System

Kerry Hubel, Palo Alto University

Phillip K. Wood, University of Missouri–Columbia

Jon R. Haber, Family Research Center, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, D.C: 1987. revised. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, D.C: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Ye Y, Bond J, Cherpitel C, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Rubio-Stipec M. The dimentionality of alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption in a cross-national perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:240–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW. Structured latent curve models. In: Cuadras C, Rao C, editors. Multivariate analysis: Future directions. Vol. 2. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz K, Heath A, Reich T, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer JR, Nurnberger JI, Schuckit MA. Can we subtype alcoholics? A latent class analysis of data from relatives of alcoholics in a multicenter family study of alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20:1462–1471. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification. 1996;13:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Indicators for chronic disease surveillance. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger C, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Type I and Type II Alcoholism: An Update. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1996;20:18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People. 2. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Edens E, Glowinski A, Grazier K, Bucholz K. The 14-year course of alcoholism in a community sample: Do men and women differ? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;93:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen S, True W, Goldberg J, Henderson W, Robinette CD. The Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry: Method of construction. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae. 1987;36:61–67. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000004591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore K, Bacon S, Hyman M. Final report to the NIAAA under contract No. (ADM) 281-76-0015. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley; 1979. The 27-year longitudinal of drinking by students in college, 1949–1976. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin. 1971;76:378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot E, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gee G, Liang J, Bennett J, Krause N, Kobayashi E, Fukaya T, Sugihara Y. Trajectories of alcohol consumption among older Japanese followed from 1987–1999. Research on Aging. 2007;29:323–347. [Google Scholar]

- Gladsjo JA, Tucker JA, Hawkins JL, Vuchinich RE. Adequacy of recall of drinking patterns and event occurrences associated with natural recovery from alcohol problems. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17:347–358. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Kaplan K, Shepard J, Moore T. Source and accuracy statement fro Wave 1 of the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bethesda: Natinal Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Fundamentals of epidemiologic data analysis. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 2. Philadelphia: Lippcott, Williams & Willkins; 1998. pp. 201–229. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson WG, Eisen S, Goldberg J, True W, Barnes JE, Vitek ME. The Vietnam Era Twin Registry: A resource for medical research. Public Health Report. 1990;105:368–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipp JR, Bauer DJ. Local solutions in the estimation of growth mixture models. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:36–53. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T. Unpublished measure. 1998. Modified Lifetime Drinking History. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Blonigen D, Koenig L, Wachsmuth W, Price R. Course of alcohol dependence among Vietnam combat veterans and non-veteran controls. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:621–639. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Blonigen D, Koenig LB, Wachsmuth W, Price RK. Course of Alcohol Dependence Among Vietnam-Era Veterans With Or Without A Positive Screen For Drug Use At Discharge and non-veteran controls. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.629. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Bucholz K, Sartor CE, Howell DN, Wood PK. Drinking trajectories from adolescence to the mid-forties among alcohol dependent males. Journal of Studies in Alcohol. 2005;66:745–755. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Koenig LB, Howell DN, Wood PK, Haber JR. Drinking trajectories from adolescence to the fifties among alcohol-dependent men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:859–869. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Seilhamer R, Bargiel K, Howell DN. Reliability of lifetime drinking history among alcohol dependent men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:333–337. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Waterman B, Heath A, True W, Bucholz K, Haber JR, Scherrer J, Fu Q. Genetic and environmental influences on offspring alcoholism: New insights using a children-of-twins design. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:1265–1272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinek E. The disease concept of alcoholism. New Brunswick, NJ: New College and University Press and Hillhouse Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig LB, Jacob T, Haber JR. Validity of the Lifetime Drinking History: A comparison of retrospective and prospective quantity-frequency measures. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:296–303. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens PH, Volovics L, De Haan Y. Measurement of lifetime exposure to alcohol: Data quality of self-administered questionnaire and impact on risk assessment. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1997;24:581–600. [Google Scholar]

- Littell R, Milliken G, Stroup W, Wolfinger R. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary: SAS Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mccrae RR. Journal of Personality. Blackwell Publishing Limited; 1999. Mainstream Personality Psychology and the Study of Religion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccrae RR, John OP. Journal of Personality. Blackwell Publishing Limited; 1992. An Introduction to the Five-Factor Model and its Applications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclachlan G, Peel D. Finite Mixture Models. New York: John Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W, Tisak J. Latent curve analysis. Psychometrika. 1990;55:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Brennan P, Schutte KK, Moos B. Older adults’ health and changes in late-life drinking patters. Aging and Mental Health. 2005;9:49–59. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331323818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus [computer program] Los Angeles: 1998–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. The development of heavy drinking and alcohol related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a U.S. national sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:290–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D, Tremblay RE. Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Development. 1999;70:1181–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Washington, D.C: Bureau of Labor Statistics; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ohio State University National Longitudinal Surveys. Ohio State University Center for Human Resource Research; Columbus: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Price RK, Risk NK, Murray KS, Virgo KS, Spitznagel EL. Twenty-five year mortality of U.S. servicement deployed in Vietnam. Predictive utility of early drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;64:309–318. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Grimm K. Using simple and complex growth models to articulate developmental change: Matching method to theory. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Robins L. The Vietnam drug user returns (Final Report). Special Action Office Monograph, Series A, No. 2. Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office; 1974. [Google Scholar]