Abstract

Naïve T cells undergo robust proliferation in lymphopenic conditions, while they remain quiescent in steady-state conditions. However, a mechanism by which naïve T cells are kept from proliferating under steady-state conditions remains unclear. Here we report that memory CD4 T cells are able to limit naïve T cell proliferation within lymphopenic hosts by modulating stimulatory functions of DC. The inhibition was mediated by IL-27, which was primarily expressed in CD8+ DC subsets as the result of memory CD4 T cell-DC interaction. IL-27 appeared to be the major mediator of inhibition as naïve T cells deficient in IL-27R were resistant to memory CD4 T cell mediated inhibition. Finally, IL-27-mediated regulation of T cell proliferation was also observed in steady-state conditions as well as during Ag-mediated immune responses. We propose a new model for maintaining peripheral T cell homeostasis via memory CD4 T cells and CD8+ DC-derived IL-27 in vivo.

Introduction

Naïve T lymphocytes, although remain quiescent in steady-state conditions, undergo rapid proliferation within lymphopenic hosts (1-3). This proliferation is induced as a part of a homeostatic process by which the immune system reinstates the homeostatic balance. Although it is believed that peptide antigens derived from the commensal microflora and/or self-antigens play a role in inducing the proliferation (4-6), those antigens are also presented to naïve T cells under steady-state conditions, during which signals to sustain survival or to optimize functions are likely to be delivered (7). Therefore, an active process directly controlling T cell proliferation depending on in vivo conditions is necessary and its failure may lead to immune dysfunctions including autoimmunity.

Heterogeneity of T cell proliferation has been noticed after adoptive T cell transfer into lymphopenic mice (4, 8). Particularly, antigen-dependent homeostatic T cell proliferation is a robust response that occurs in the complete absence of IL-7 (4, 8). Since this response is likely associated with immunopathology resulting from uncontrolled T cell activation (9, 10), understanding mechanisms regulating the proliferation is of great importance.

T cell proliferation induced within immunodeficient hosts gradually wanes over a period of several weeks following transfer. As a result, T cells displaying memory phenotypes are generated, although only a few millions of these cells are typically found in the lymphoid tissues of these recipients (11-13). Since transferred naïve T cells either differentiate into memory phenotype cells or die, and there is no endogenous source of naïve T cells in these hosts, the lymphopenic status remains unchanged except a relatively small number of memory phenotype T cells derived from the initial transfer. Importantly, those memory phenotype T cells are fully capable of inhibiting the proliferation of naïve T cells that are newly transferred into the recipients (12, 14). How naive T cells are kept from proliferating in memory T cell-enriched lymphopenic conditions has not been previously explored. Thus, understanding mechanism(s) underlying the proliferation may provide fundamental insight into the regulation of homeostatic T cell proliferation.

One key player involved in T cell activation/proliferation is antigen presenting cell (APC), particularly dendritic cell (DC). In addition to inducing T cell immunity post infection or immunization, DC are also critical for naïve CD4 T cells to undergo proliferation in lymphopenic hosts (15). DC also deliver tolerogenic signals (16); it was recently demonstrated that DC acquire IL-27-dependent regulatory functions, inducing IL-10-producing T cell tolerance and suppressing autoimmune neuroinflammation (16). Consistent with this, IL-27R−/− or IL-27−/− mice were highly susceptible to the disease and generated more IL-17+ encephalitogenic T cells (17, 18). IL-27 also suppresses CD28-mediated IL-2 production and T cell proliferation via suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) (19-21).

Here we examined the hypothesis that memory phenotype CD4 T cells (which will be referred to as ‘memory’ T cells hereafter) inhibit naïve T cell proliferation by altering stimulatory functions of APC. Memory CD4 T cells fully inhibited the proliferation of both naïve CD4 and CD8 T cells in lymphopenic hosts. This inhibition was found only when both naïve and memory T cells interact with the same APC; i.e., the inhibition was abolished when memory CD4-APC interaction was absent even under memory cell enriched conditions. The expression of IL-27 was found elevated when naïve T cell proliferation was inhibited. Naïve T cells deficient in IL-27R underwent robust proliferation regardless of the presence of memory T cells in vivo. CD8+ DC were the dominant population that expressed high levels of IL-27 following CD4 T cell-DC interaction. IFNγ was necessary to induce IL-27 expression in CD8+ DC. Therefore, IL-27 expressed by DC directly controls naïve T cell proliferation and the memory CD4 T cell interaction with the DC controls the IL-27 expression. Our results highlight a novel feedback mechanism involving memory CD4 T cells and DC derived IL-27, from which homeostatic regulation of naïve T cells is kept under control.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Ly5.1 C57BL/6, Thy1.1 C57BL/6, C57BL/6 TCRβ−/−, C57BL/6 MHC II−/− (H2dlAb1-Ea), C57BL/6 Rag2−/−, C57BL/6 OT-II TCR Tg, C57BL/6 IFNγR−/−, C57BL/6 IFNγ−/−, and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). B10.A Rag2−/− and Ly5.1 B10.A mice were kindly provided from Dr. William Paul (NIH). C57BL/6 IL-27R−/− mice were provided from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). All the mice were maintained under specific pathogen free facility located in the Lerner Research Institute. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with approved protocols for the Cleveland Clinic Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee.

Cell isolation and adoptive transfer

Donor naïve T cells were isolated from lymph nodes. In brief, lymph node cells were incubated with FITC conjugated anti-MHC II (M5/114), anti-FcγR (2.4G2), anti-NK1.1 (PK136), and anti-B220 (RA3-6B2) antibodies. Labeled cells were subsequently incubated with anti-FITC microbeads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA) and then T cells were purified through magnetic field isolation. Cells were then labeled with PE-anti-CD44 (IM7) and APC-anti-CD4 (RM4-5) or APC-anti-CD8 (53-6.7). CD44low naïve T cells were sorted using a FACSAria high-speed cell sorter (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Purity is typically > 99%. As the primary transfer, Rag−/− or TCRβ−/− mice were transferred with 3 × 106 purified CD4 T cells. Four weeks later the mice received the secondary naïve T cells. 1 × 106 naïve T cells were intravenously transferred into recipients. In some experiments examining cell proliferation, T cells were labeled with CFSE (Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester, Molecular Probe, Carlsbad, CA). The recipients were sacrificed 7 days post transfer, and proliferation (as well as total cell recovery) was determined by FACS analysis using a FACSCalibur or a FACS LSRII and a FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR). The following antibodies were used: anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-Ly5.1 (A20), anti-Thy1.1 (HIS51), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-I-Ab (AF6-120.1), anti-Kb (AF6-88.5), and anti-I-Ek (14-4-4S). All antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) or PharMingen (San Diego, CA). In some experiments examining T cell proliferation in vivo, the recipients were injected with 1mg BrdU one day prior to sacrifice. BrdU incorporation was determined using a BrdU staining kit (PharMingen) according to the manufacturer’s manual. In some experiment recipients were subcutaneously immunized with OVA protein (Sigma-Aldrich) plus LPS (Sigma-Aldrich).

Bone marrow chimeras

Lethally irradiated mice were transferred with 15-20 × 106 BM cells isolated from the donor mice as indicated in the text. The BM recipients were intraperitoneally injected with gentamycin at day 0 and 2 post transfer. Six weeks later the recipients were bled and reconstitution was confirmed prior to the transfer experiments. In the experiments examining CD4-mediated CD4 T cell proliferation described in Figure 2, the BM chimera recipients were injected with anti-NK1.1 Ab (250μg/mouse, −1 and 3, 6) prior to the secondary donor CD4 T cell transfer. In some experiments, 1:1 mixture of Ly5.1 WT and Ly5.2 IL-27R−/− BM cells were injected into lethally irradiated recipients. Reconstitution of each T cell type was monitored every two weeks post reconstitution.

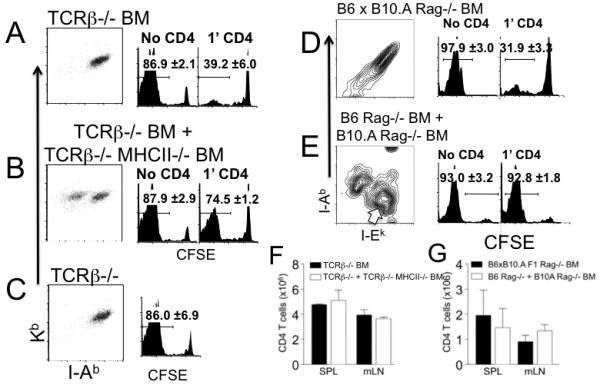

Figure 2. Memory CD4 T cells suppress naïve T cell proliferation through interacting the same APC.

A and B. Lethally irradiated Rag−/− mice were transferred with BM cells from TCRβ−/− (A) or 1:1 mixture of TCRβ−/− and TCRβ−/− MHC II−/− mice (B). After 6 weeks of BM reconstitution, MHC I and MHC II expression of CD11c+ splenic DCs was examined by FACS analysis. The dot plots show the expression of Kb and I-Ab of CD11c+ splenic DC. The reconstituted mice were transferred with 3 × 106 Thy1.2 CD4 T cells (1′ CD4). CFSE labeled Thy1.1 naïve CD8 T cell transfer was performed 4 weeks post the 1′ CD4 T cell transfer. CFSE profiles of the Thy1.1 CD8 T cells were examined 7 days post transfer (A and B, right histogram). CD8 T cells were also transferred into reconstituted recipients without the 1′ CD4 transfer (A and B, left histogram). Histograms shown are CFSE profiles of Thy1.1-gated CD8 T cells. C. CFSE labeled naïve Thy1.1 CD8 T cells were transferred into TCRβ−/− recipients and their proliferation was examined 7 days post transfer. Data are representative of 4 individually tested mice from two independent experiments. The average ± SD of the proportion of T cells that fully diluted CFSE is indicated. D and E. Irradiated B6 × B10.A Rag−/− F1 mice were reconstituted with BM cells from B6 × B10.A Rag−/− F1 (D) or with 1:1 mixture of BM cells from B6 Rag−/− and B10.A Rag−/− mice (E). After 6 weeks of BM transfer, reconstitution was confirmed by FACS analysis. Contour plots show expected I-Ab and I-Ek expression of CD11c+ splenic DCs (D and E). BM chimeras generated above were transferred with 3 × 106 1′ I-Ab restricted (and I-Ek/I-Ak tolerant) Thy1.1 CD4 T cells (please see Supplementary Figure S4). Four weeks post the 1′ transfer, the recipients were transferred with CFSE labeled Ly5.1 I-Ak/I-Ek restricted (I-Ab tolerant) FACS sorted naïve CD4 T cells. 250γg anti-NK1.1 mAb was injected at days -1, 3 and 6 of the second transfer. CFSE profiles were examined 7 days post transfer (right histogram). Naïve CD4 T cells were also transferred into reconstituted recipients without the 1′ CD4 transfer (left histogram). Histograms shown are CFSE profiles of Ly5.1-gated CD4 T cells. Data are representative of 4-5 individually tested mice from two independent experiments. The average ± SD of the proportion of T cells that fully diluted CFSE is indicated. (F) Total numbers of 1′ memory CD4 T cells from the groups described in the Figure 2A and 2B were counted by FACS analysis. (G) Total numbers of 1′ memory CD4 T cells from the groups described in the Figure 2D and 2E were counted. Data shown are the average ± SD from two independent experiments.

Real time quantitative PCR

CD11c+ splenic DC were isolated from wild type, Rag−/−, and Rag−/− mice that received CD4 T cells 4 weeks earlier. DC were further sorted into different subsets based on the expression of CD8. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was subsequently obtained using a SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real time PCR was performed using the Ebi3- and p28- specific primers and probe sets (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA) and ABI 7500 PCR machine (Applied Biosystem). In some experiments, bone marrow derived DC were generated, and cocultured with OT-II CD4 T cells with or without 1μM OVA peptide for 48 hours. CD8+ and CD8− CD11c+ DC from the culture were further sorted by FACS and subsequently analyzed for the expression of IL-27 subunits. All gene expression results are expressed as arbitrary units relative to expression of the endogenous control GAPDH. Relative expression of each gene is quantified using the formula, 2^(ΔΔCT).

Data analysis

Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t-test using the Prism 4 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). p<0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Experimental model

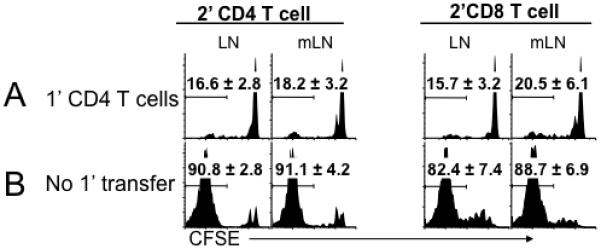

T cell proliferation induced by a homeostatic mechanism is determined by the lymphopenic status of hosts; naïve T cells remain quiescent in lymphocyte-sufficient but rapidly proliferate in lymphocyte-deficient hosts. We and others previously reported that memory CD4 T cells play a key role in limiting naïve CD4 T cell proliferation (12, 14). To investigate the underlying mechanism we employed a double transfer strategy as previously reported (Figure S1) (12). CD4 T cells (1′ transfer) were introduced into lymphopenic mice (Rag−/− or TCRβ−/−), allowing them to expand, differentiate into memory cells, and populate the peripheral lymphoid tissues of the recipients. Four weeks later the recipients received a new cohort of CFSE labeled Thy1.1 (or Ly5.1 in some experiments) CD44low naïve T cells (2′ transfer) and the CFSE dilution was determined 7 days after transfer. Of note, almost 100% of the 1′ CD4 T cells acquired a memory phenotype, although their cellularity within the secondary lymphoid tissues was ~2 × 106 at the time of the 2′ transfer, indicating a severe lymphopenic status of these recipients (12, 22). As previously reported (12), the preexisting 1′ memory CD4 T cells fully inhibited the proliferation of 2′ naïve CD4 T cells (Figure 1A). Interestingly, memory CD4 T cells inhibited naïve CD8 T cell proliferation as well (Figure 1A). The inhibition was not found without the 1′ transfer (Figure 1B). Although it was previously proposed that memory T cells with a given specificity may prevent responses of naïve T cells of the same or related specificity (23), CD4 and CD8 T cells are not likely to share specificity; thus, an alternative mechanism may operate.

Figure 1. Preexisting memory phenotype CD4 T cells inhibit naïve T cell proliferation.

A. Groups of Rag−/− mice were transferred with 3 × 106 Thy1.2 CD4 T cells (1′ CD4). Subsequently, the recipients were transferred with CFSE labeled FACS sorted Thy1.1 naïve 2′ T cells (1 × 106, containing both CD4 and CD8) 4 weeks post the 1′ CD4 transfer. Histograms shown are CFSE profiles of Thy1.1-gated T cells (2′ CD4 or 2′ CD8) examined 7 days post transfer. B. CFSE labeled Thy1.1 naïve T cells were transferred into Rag−/− mice. CFSE profiles were determined 7 days post transfer. The experiments were repeated three times and similar results were observed. The average ± SD of the proportion of T cells that fully diluted CFSE is indicated. LN, peripheral LN; mLN, mesenteric LN. Similar results were found in the spleen (not shown).

Memory CD4 T cell-mediated inhibition of naïve CD8 T cell proliferation operates through APC

Interaction of T cells expressing high affinity antigen receptors with APC can downregulate peptide-MHC complexes on the APC, preventing further activation of newly recruited naïve T cells (24). We thus hypothesized that memory CD4 T cells may downmodulate stimulatory functions of APC and that this interaction between memory CD4 T cells and APC may be essential to restrain naïve cell proliferation. The hypothesis also predicts that APC that do not interact with memory CD4 T cells may preserve stimulatory functions even in the presence of them. To test this hypothesis BM chimeras in which interactions between APC and memory CD4 T cells are restricted were generated. Irradiated Rag−/− mice were reconstituted with BM cells from TCRβ−/− (Figure 2A) or with 1:1 mixture of BM cells from TCRβ−/− and TCRβ−/− MHCII−/− mice (Figure 2B). The recipients remained T cell-deficient but had APC expressing both MHCI and MHCII (Figure 2A), or two APC populations; one expressing both MHCI and MHCII and one expressing MHCI alone (Figure 2B). MHC expression on CD11c+ splenic DC from these chimeras confirmed the appropriate reconstitution (Figure 2A and 2B). The reconstituted mice received 1′ CD4 T cells and CFSE labeled naïve 2’ CD8 T cells 4 weeks later. Consistent with results shown in Figure 1, CD8 T cells failed to proliferate in mice in which APC expressed both MHCI and MHCII (Figure 2A right panel). By contrast, a substantial proliferation was found in recipients in which ~50% of the APC were MHCII−/− (Figure 2B right panel). This proliferation was not due to different numbers of 1′ memory CD4 T cells generated in these recipients since the total numbers of CD4 T cells derived from the 1′ transfer were similar (Figure 2F). CD8 T cells underwent robust proliferation in both types of BM chimeras without 1′ CD4 transfer (Figure 2A and 2B left panel) or in control TCRβ−/− recipients (Figure 2C). Therefore, memory CD4 T cell interaction with MHCII+ APC may limit the proliferation of naïve CD8 T cells that interact with the same APC.

Memory CD4 T cell mediated inhibition of naïve CD4 T cell proliferation operates through APC

To examine if memory CD4 T cells similarly regulate naïve CD4 proliferation we used CD4 T cells restricted to different MHCII haplotype molecules (illustrated in Figure S2). To establish recipients in which APC express different MHCII restriction elements, B6 × B10.A F1 Rag−/− mice were reconstituted with B6 × B10.A F1 (I-Abxk) Rag−/− BM (Figure 2D) or 1:1 mixture of B6 (I-Ab) Rag−/− and B10.A (I-Ak/I-Ek) Rag−/− BM cells (Figure 2E). APC from the former recipients are expected to express both I-Ab and I-Ak/I-Ek (Figure 2D), while APC from the latter recipients are expected to express either I-Ab or I-Ak/I-Ek (Figure 2E). Appropriate reconstitution was confirmed by examining MHCII expression in splenic DC at 6 weeks after reconstitution (Figure 2D and 2E).

Because of alloreacitivity CD4 T cells that are restricted to one MHCII but tolerant to another MHCII element were needed. Since developing CD4 T cells are restricted to selecting MHCII during thymic development (25), B10.A BM cells transferred into lethally irradiated B6 Rag−/− mice are expected to develop into CD4 T cells that are restricted to I-Ab but tolerant to I-Ak/I-Ek (Figure S3A). Likewise, B6 BM cells transferred into lethally irradiated B10.A Rag−/− mice are expected to develop into CD4 T cells that are restricted to I-Ak/I-Ek but tolerant to I-Ab (Figure S3A). To examine if T cells obtained above behave as expected a proof-of-principle experiment was performed. Sorted naïve CD4 T cells from B10.A Rag−/− recipients reconstituted with B6 BM cells (I-AkI-Ek restricted/I-Ab tolerant) were transferred into B10.A Rag−/− or B6 Rag−/− recipients and the proliferation was assessed. As expected, those CD4 T cells fully diluted the CFSE content only within I-Ak-expressing B10.A Rag−/− but not within I-Ab-expressing B6 Rag−/− recipients (Figure S3B, filled arrow), indicating a MHCII-restricted T cell proliferation. Interestingly, IL-7-dependent homeostatic proliferation ((4, 8); i.e., 1-2 cell division) was still observed in B6 Rag−/− recipients (Figure S3B, open arrow), suggesting that the cytokine-dependent proliferation is not a MHC-restricted response, although MHCII molecules are still necessary (4, 8).

CD4 T cells (1′) restricted to I-Ab MHCII elements were isolated and then transferred into reconstituted recipients described in Figures 2D and 2E. I-Ak/I-Ek restricted (and CFSE labeled) 2′ naive CD4 T cells were transferred 4 weeks after the 1′ CD4 transfer. Consistent with the results seen in CD8 T cells, the preexisting I-Ab-restricted memory CD4 T cells efficiently inhibited 2′ CD4 T cell proliferation when APC expressed both MHCII haplotype molecules (Figure 2D right panel). By contrast, the same 2′ naïve CD4 T cells underwent robust proliferation when transferred into recipients where I-Ak/I-Ek-expressing APC (Figure 2E open arrow) do not express I-Ab and therefore do not interact with memory 1′ CD4 T cells (Figure 2E right panel). Notably, the total numbers of memory 1′ CD4 T cells in both recipients were similar, indicating that the different proliferation of 2′ naïve T cells is not due to a discrepancy in the memory CD4 T cell numbers present in these recipients (Figure 2G). Robust proliferation of 2′ CD4 T cells was equally observed in both types of recipients without 1′ CD4 T cell transfer (Figure 2D and 2E left panel). Therefore, these results strongly suggest that APC play a central role in controlling naïve T cell proliferation and that memory CD4 T cells directly control the stimulatory function of the APC via TCR-MHCII interactions.

Continuous presence of memory CD4 T cells is necessary to mediate the inhibition

If stimulatory functions of APC are downregulated by memory CD4 T cells, those APC may remain non-stimulatory, or alternatively, continuous presence of memory CD4 T cells may be required to maintain the functions. To directly test this possibility, preexisting memory CD4 T cells expressing Thy1.2 were depleted using anti-Thy1.2 Ab when naïve T cells expressing Thy1.1 were transferred. As shown in Figure 3, the proliferation of both Thy1.1 naïve CD4 and CD8 T cell proliferation was significantly restored upon memory cell depletion. A partial restoration of Thy1.1 T cell proliferation could be due to a homeostatic competition by residual non-depleted memory T cells that are also likely to undergo proliferation under this condition (26). Our results suggest that APC-mediated control of naïve T cell proliferation is a reversible process that is directly dependent on the presence of memory CD4 T cells.

Figure 3. Continuous presence of memory CD4 T cells is necessary to inhibit naïve T cell proliferation.

Rag−/− mice that received 1′ Thy1.2 CD4 T cells and 2′ CFSE labeled Thy1.1 naïve T cells as described above were injected with 250μg anti-Thy1.2 Ab at the time of 2′ naïve T cell injection. Shown are the CFSE profiles of donor T cells in the LN tissues examined 7 days post the 2′ transfer. Similar results were observed in the spleen tissues. The number shown in the histograms indicates the proportion of donor T cells that fully diluted the CFSE. Similar results were observed from two independent experiments.

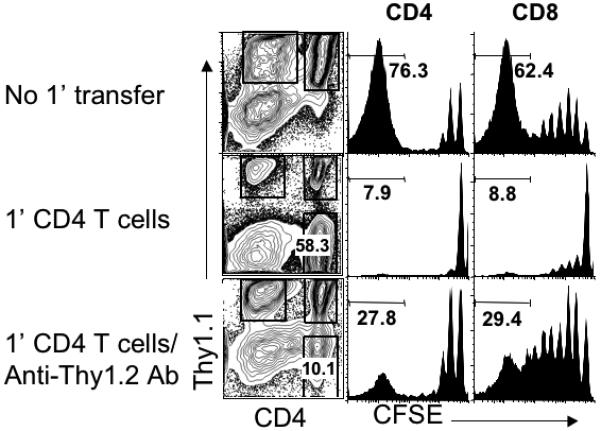

IL-27 mediates memory CD4 T cell-induced inhibition of naïve T cell proliferation

To examine mechanism(s) underlying APC-mediated control of naïve T cell proliferation, we first compared surface expression of molecules involved in T cell activation/inhibition. No significant differences in the expression of MHC as well as costimulatory molecules were found in CD11c+ DC isolated from wild type and lymphopenic TCRβ−/− (and Rag−/−, data not shown) mice. IL-27 has recently been shown to be induced by DC that deliver tolerogenic signals to T cells (16) and to suppress T cell IL-2 production (19). To directly test if IL-27 is involved, we used naïve CD4 T cells deficient in IL-27R (20). CD4 T cells were transferred into TCRβ−/− mice. Four weeks later CFSE labeled CD44low naive IL-27R−/− or wild type CD4 T cells were transferred into the recipients. To our surprise, IL-27R−/− CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD8 (data not shown) T cells were refractory to memory T cell-induced inhibition, while wild type CD4 T cell proliferation was fully suppressed. Of note, the proliferation of WT and IL-27R−/− T cells was similar in lymphopenic conditions without the 1′ CD4 transfer (data not shown), suggesting that IL-27R−/− T cells are not more prone to proliferation compared to WT cells in the absence of memory CD4 T cells. Therefore, IL-27 expressed in the presence of memory CD4 T cells appears to signal the IL-27R on naive CD4 T cells and directly prevents the proliferation.

Figure 4. IL-27 induced by CD4 T cells inhibits naïve T cell proliferation.

A. Groups of Thy1.1 TCRβ−/− mice were transferred with 3 × 106 Thy1.1 CD4 T cells (1′ CD4) and with 1 × 106 CFSE labeled Thy1.2 naïve CD4 T cells isolated from wild type or IL-27R−/− mice at 4 weeks post 1′ transfer. CFSE profiles of Thy1.2-gated CD4 T cells were examined 7 days post transfer. Histograms shown are representative of 4 individually tested mice from two independent experiments. The average ± SD of the proportion of T cells that fully diluted CFSE is indicated. LN, peripheral LN; mLN, mesenteric LN. Similar results were found in the spleen (not shown). B. CD11c+ DC were FACS sorted from spleen cells of wild type, Rag−/−, and Rag−/− mice that received 1′ CD4 T cells (4 weeks earlier). Expression of Ebi3 and p28 was measured by quantitative PCR analysis. The expression was normalized to endogenous control GAPDH. Data shown are the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. *, p<0.01; **, p<0.05.

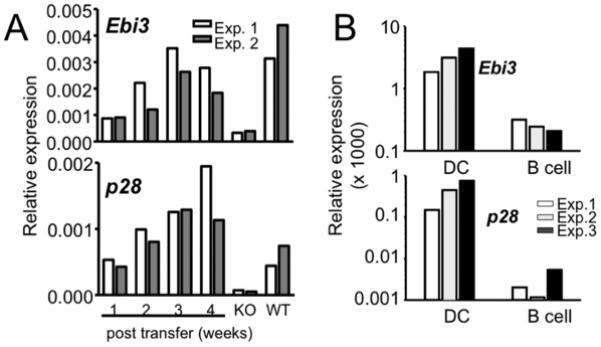

Because activated APC are the major source of IL-27 (27) and DC are the primary APC inducing proliferation of both naïve and memory CD4 T cells in lymphopenic settings (15), we next examined if DC mediate the inhibition by releasing IL-27. CD11c+ DC were isolated from WT and Rag−/− mice and examined for the expression of IL-27 subunits, Ebi3 and p28. Indeed, the expression of both subunits was significantly diminished in DC isolated from lymphopenic Rag−/− mice compared to those DC isolated from wild type mice (Figure 4B). Importantly, IL-27 expression in DC dramatically increased when Rag−/− mice received CD4 T cells (Figure 4B). Likewise, IL-27 expression was lower in DC isolated from TCRβ−/− compared to WT mice and the expression was also restored following CD4 T cell transfer (data not shown). IL-27 expression increased as early as 7 days after CD4 transfer, and it continued to increase up to 4 weeks post transfer (Figure 5A). IL-27 expression was mostly found in DC, and B cells expressed little IL-27, suggesting that DC are the primary source of IL-27 (Figure 5B). Therefore, the lack of CD4 T cells appears to be responsible for the defects in IL-27 expression.

Figure 5. IL-27 is primarily expressed by DC.

(A) Kinetics of IL-27 expression following CD4 T cell transfer. Groups of TCRβ−/− mice were transferred with CD4 T cells. IL-27 expression in CD11c+ splenic DC was weekly measured by qPCR. Wild type B6 and TCRβ−/− mice are included as positive and negative control, respectively. (B) IL-27 subunits expression by DCs and B cells. CD11c+ DCs and CD19+ B cells were sorted from splenocytes of TCRβ−/− mice that received CD4 T cells 4 weeks earlier. Expression of IL-27 subunits was subsequently examined. Experiments were repeated three times as shown.

IL-27 is highly expressed in CD8+ DC

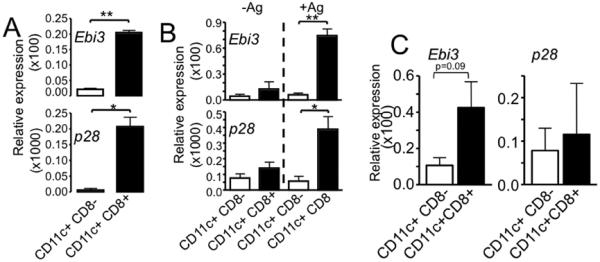

Functional specialization of DC subsets particularly in preventing self-reactive responses has been described (28). To examine if IL-27 seen in wild type mice, or lymphopenic mice that receive CD4 T cells is expressed by a subset of DC we isolated different CD11c+ DC subsets from wild type mice based on the expression of CD8 and measured IL-27 expression. We found that IL-27 subunits were primarily expressed in CD8+ DC subsets, while CD8− CD11c+ DC expressed little IL-27 (Figure 6A). Selective expression of IL-27 in CD8+ DC was further confirmed in DC-OT-II coculture experiments. The addition of antigen in the culture significantly increased IL-27 expression only in CD8+ DC subsets (Figure 6B). Lastly, CD8+ DC subsets isolated from Rag−/− mice that received CD4 T cells expressed elevated levels of IL-27, particularly Ebi3 (Figure 6C). Although the elevation was not statistically significant, the increase was highly reproducible. Furthermore, it should be noted that the IL-27 expression continues to rise after CD4 T cell transfer (Figure 5A). Therefore, these results suggest that the level of IL-27 expression in CD8+ DC increased possibly as a result of T cell activation both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 6. IL-27 is primarily expressed by CD8+ DC subsets.

A. Splenic DC from wild type B6 mice were sorted into different subsets based on the expression of CD8. Expression of IL-27 subsets was determined by real time PCR analysis. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results. B. Bone marrow derived DCs were cocultured with OVA-specific OT-II CD4 T cells with or without OVA peptide antigen. After 48 hours of culture, DCs were sorted from the culture into CD8+ and CD8− CD11c+ cells, and the expression of IL-27 subunits was determined by qPCR analysis. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results. C. CD8+ and CD8− splenic DC subsets were purified from Rag−/− mice that received CD4 T cells 7 days earlier by cell sorting and IL-27 expression was examined by qPCR. Expression of Ebi3 and p28 was normalized to endogenous control GAPDH. The data shown is average ± SD from two independent experiments. *, p<0.01; **, p<0.05.

IFNγ induces IL-27 expression in CD8+ DC

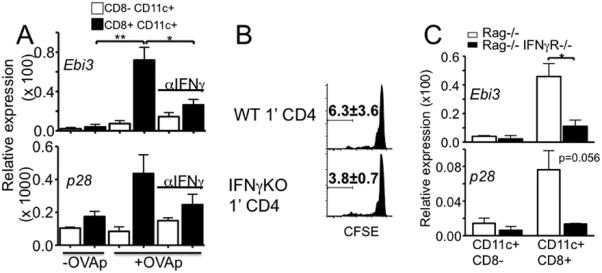

Since it was recently reported that IFNγ plays a critical role in inducing IL-27 production in DC (29), we tested if IFNγ is necessary. Neutralizing IFNγ during in vitro coculture of OT-II and DC significantly diminished Ag-induced IL-27 expression in CD8+ DC (Figure 7A). This finding prompted us to test if T cell-derived IFNγ is critical to induce IL-27 and thus to limit naïve T cell proliferation in vivo. To test this possibility, Rag−/− recipients were transferred with IFNγ-deficient or WT 1′ CD4, and then with CFSE labeled naïve CD4 T cells 4 weeks post the 1′ transfer. However, IFNγ-deficient 1′ CD4 T cell efficiently inhibited naïve cell proliferation (Figure 7B), which is likely due to recipient cells such as NK cells that are still capable of expressing IFNγ (data not shown). Yet, it should be noted that IFNγ possibly derived from NK cells is unable to induce sufficient level of IL-27 in the absence of CD4 T cells. Indeed, IFNγ production by NK cells requires the presence of CD4 T cells (30). We instead used Rag−/− mice deficient in IFNγR as recipients. CD4 T cells were transferred into these mice, and DC expression of IL-27 was measured by PCR. As shown in Figure 7C, CD8+ DC expressed lower level of IL-27, strongly suggesting the importance of IFNγ-mediated induction of IL-27 in CD8+ DC. Therefore, it is expected that 1′ CD4 T cells would be unable to inhibit naïve cell proliferation in these recipients mainly due to the defects in IL-27 expression. However, we were unable to test this possibility because IFNγR−/− Rag−/− recipients of CD4 T cells developed very severe colitis even within a week post transfer (unpublished observation). Whether the lack of IL-27 expression in IFNγR−/− Rag−/− mice is due to high level of inflammation is not clear. IL-27 is known to suppress Th17 development that is directly associated with colitis (31, 32), although the role of IL-27 in the development of colonic inflammation remains controversial (33). Notwithstanding this unexpected observation, these results clearly suggest the importance of IFNγ- and potentially IL-27-mediated regulation of T cell proliferation and activation.

Figure 7. IFNγ induces IL-27 expression in CD8+ DC.

A. OT-II T cells were cocultured with BM derived DC in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti-IFNγ Ab. CD8+ and CD8− DC were sorted from the culture 48 hours later. IL-27 expression was examined by qPCR. Coculture without peptide was included as a control. The data shown is average ± SD from two independent experiments. B. Rag−/− mice were transferred with wild type or IFNγ−/− CD4 T cells. Four weeks later, CFSE labeled Thy1.1 naïve CD4 T cells were transferred into the recipients. CFSE profiles of newly transferred cells were determined 7 days post transfer. The data shown is average ± SD from two independent experiments. C. CD4 T cells were transferred into Rag−/− or Rag−/− IFNγR−/− recipients. CD8+ and CD8− splenic DC were sorted 10 days post transfer and IL-27 expression was examined by qPCR. *, p<0.01; **, p<0.05.

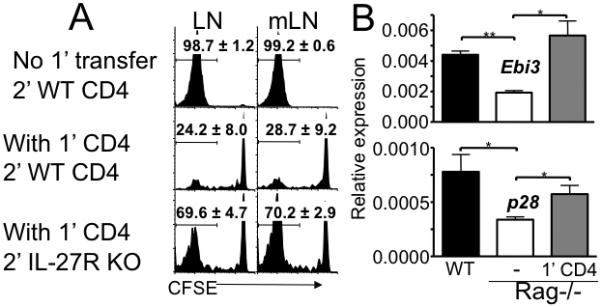

Homeostatic role of IL-27 in steady-state conditions

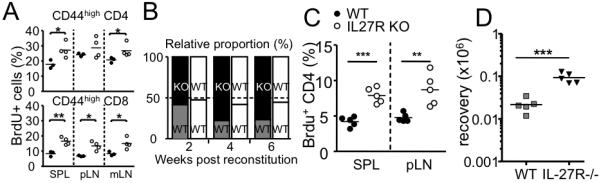

Although IL-27 controls T cell proliferation under lymphopenic settings, whether it plays a similar role in a non-lymphopenic setting was next examined. Mice deficient in IL-27R were reported healthy and fertile, and no significant differences in gross or in body weights between wild type and deficient animals were found (20). Moreover, development and differentiation of lymphocytes in the lymphoid tissues were found to be normal in these mice (20). However, we noticed that in vivo proliferation of CD44high memory phenotype T cells was substantially higher in IL-27R−/− than in wild type mice (Figure 8A). The importance of IL-27R in T cell expansion was better demonstrated in Rag−/− mice that are reconstituted with 1:1 mixture of Ly5.1 WT and Ly5.2 IL-27R−/− BM cells. As shown in Figure 7B, IL-27R−/− BM-derived T cells significantly outgrew WT BM-derived T cells over time; ~80% of peripheral T cells were of IL-27R−/− BM origin. On the other hand, equal reconstitution of Ly5.1 WT and Ly5.2 WT T cells was found in control mice (Figure 8B). Of note, comparable repopulation of WT and IL-27R−/− T cells at early time post reconstitution strongly suggests that the outgrowth of IL-27R−/− T cells is not due to a competitive advantage during thymic development (Figure 8B). Both IL-27R−/− CD4 (Figure 8C) and CD8 T cells (data not shown) from the reconstituted mice displayed a greater proliferation activity compared to WT T cells. On the contrary, equal proliferation was found in control mice (data not shown). Consistent with these results, CD44high memory phenotype T cells generated from IL-27R−/− BM cells were substantially abundant than those generated from WT BM cells (Figure S4). Therefore, IL-27 may regulate the generation as well as the maintenance of memory phenotype T cells in steady-state conditions.

Figure 8. IL-27 regulates T cell proliferation in steady-state conditions as well as during Ag-mediated immune responses.

A. Groups of wild type (filled circle) and IL-27R−/− (open circle) mice were injected with BrdU. Mice were sacrificed 24 hours later and BrdU incorporation by CD44high memory phenotype T cells was examined. Each symbol represents individually tested mice. B and C. Groups of irradiated Rag−/− mice were reconstituted with 1:1 mixture of Ly5.1 WT plus Ly5.2 IL-27R−/− (or Ly5.2 WT) BM cells. B. Following the reconstitution, mice were bled every two weeks, and the relative proportion of Ly5.1/Ly5.2 T cells was examined. C. In vivo proliferation of reconstituted CD4 T cells was examined by BrdU incorporation experiments as described above. D. 5 × 105 WT or IL-27R−/− Ly5.1 OT-II CD4 T cells were transferred into B6 recipients. The recipients were subsequently immunized s.c. with 50γg OVA protein plus 10μg LPS. Ly5.1 T cell expansion within the draining lymph node was determined by FACS analysis 7 days post immunization. Each symbol represents individually tested mouse. *, p<0.01; **, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001.

Lastly, whether IL-27 plays a role in the generation of Ag specific effector CD4 T cells was examined. WT B6 mice were transferred with WT or IL-27R−/− OT-II CD4 T cells and subsequently immunized with OVA. Expansion of OT-II T cells was then monitored. As shown in Figure 8D, the expansion of IL-27R−/− OT-II T cells was significantly greater than that of WT OT-II T cells, further suggesting a key regulatory role of IL-27 during Ag mediated T cell responses.

Discussion

Lymphocyte levels in the periphery determine proliferative behaviors of naïve T cells; in lymphopenic conditions naïve T cells proliferate, while in steady-state conditions they remain quiescent. Efforts have been made to understand underlying mechanisms that induce T cell proliferation in lymphopenic hosts (4). However, how T cells are prevented from proliferating under steady-state conditions has not been formally explored. We report here that naïve T cell proliferation is primarily determined by stimulatory functions of APC particularly of DC (23), and that memory CD4 T cells directly modulate the conditions of the DC. We identified that IL-27 produced by CD8+ DC subsets through interaction with memory CD4 T cells plays a central role in controlling naïve T cell proliferation by directly acting on naïve T cells. Furthermore, IL-27-mediated regulation of T cell proliferation was also found in resting conditions as well as Ag-mediated immune responses.

A simplistic view of T cell homeostasis would be a soluble factor-mediated competition between lymphocytes. In steady-state conditions factors available to T cells may be sufficient to maintain survival but not enough to induce proliferation, whereas in lymphopenic conditions increased availability of these factors may deliver signals sufficient to induce proliferation. IL-7 has been well characterized to explain this model (34-37). Indeed, IL-7 levels in the circulation inversely correlate with T cell levels (37, 38). However, a cytokine-independent (TCR-MHC-dependent) proliferation found in lymphopenic hosts (4, 8), which is the major response of interest in this study, is not supported by this model. Moreover, this is the dominant response observed within severe lymphopenic settings and is believed to result in immunopathology that often develops in such conditions.

Our results provide key mechanisms that explain a fundamental basis of T cell homeostasis. First, memory phenotype CD4 T cells are the regulators of peripheral T cell homeostasis. Rag−/− mice populated with memory cells efficiently prevent newly transferred naïve T cells from proliferating (12, 23). Memory Marilyn TCR transgenic CD4 T cells transferred into Rag/γc−/− recipients suppress naïve Marilyn CD4 T cell proliferation (14). Eliminating these memory T cells allowed naïve T cells to proliferate. Therefore, we would argue that the lack of memory T cells is the primary driving force of naïve T cell proliferation. Once memory cells occupy the peripheral lymphoid tissues, it becomes a ‘homeostatically stable’ environment regardless of naïve T cells, as demonstrated in our study.

Second, memory CD4 T cells regulate naïve cell responses through APC. This type of regulation was previously reported during immune responses. CD4 T cells engage and ‘condition’ DC through a CD40L-CD40 interaction, and these DC can promote an optimal CD8 differentiation into cytotoxic effector cells (39). Likewise, orally immunized memory T cells use IL-4 and IL-10 to ‘educate’ antigen-presenting DC, which then induce naïve T cells to produce the same cytokines as those produced by memory T cells (40). Our results indicate that in lymphopenic (and non-inflammatory) and even in steady-state conditions a similar type of regulatory mechanism may operate. Memory CD4 T cells interact with APC, particularly CD8+ DC, alter their stimulatory functions, and in turn prevent naive T cell proliferation. CD40L-CD40 interaction was not involved in this process as memory CD4 T cells within CD40-deficient Rag−/− mice were fully capable of inhibiting naïve T cell proliferation (data not shown).

Third, IL-27 expressed by CD8+ DC subsets directly inhibits naïve T cell proliferation. IL-27 plays both pro- and anti-inflammatory roles in both innate and adaptive immunity (27). IL-27 production by APC can be induced by inflammation-mediated signals associated with pathogens (41, 42). The activation of the NFκB pathway might induce high levels of IL-27 production, which may synergize with IL-12 to promote Th1 immunity (20, 42). Under non-inflammatory lymphopenic conditions described in this study, IL-27 expression in DC appears to be mainly controlled by IFNγ (8, 29). Moreover, T cells that lack the IL-27 receptor expanded better even during resting conditions as well as Ag-mediated immune responses. It is possible that different IL-27 levels might explain different action of IL-27 on T cells (43); low IL-27 produced within non-inflammatory conditions might result in anti-proliferative function, while high IL-27 produced under inflammatory conditions may favor Th1 development. Consistently, IL-27R−/− CD4 T cells proliferate better following in vitro activation (21). Likewise, CD4 T cells from IL-27R−/− mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii expanded better, and their IL-2 production was also higher (44). IL-2 expression in activated T cells was directly suppressed by IL-27 in vitro (21). In support of this, IL-27R−/− OT-II CD4 T cells expanded greater when immunized in vivo with OVA peptide. Although the mechanism by which IL-27 mediates anti-proliferative functions needs further examination, SOCS3 induced by IL-27 may be involved in inhibiting T cell proliferation possibly via a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1 (21, 45).

Although IL-27 appears to be the major mediator regulating naïve T cell proliferation, it is unclear why continued presence of memory CD4 T cells is necessary to mediate the inhibition. The level of IL-27 expressed in vivo may be very low, and the half-life of IL-27 could be short (46). Thus, the action of IL-27 may be very local unlike inflammatory cytokines that permeate an active lymph node and signal the majority of cells therein (47). Likewise, IL-2 needed for secondary expansion of memory CD8 T cells was reported to be of local autocrine origin (48). Whether IL-27 is the sole mediator or whether additional factors are involved depending on the type of responses will require further investigation. We believe that Tregs are not involved in the mode of homeostatic regulation reported here, as we observed efficient IL-27 expression even after transfer of CD25neg CD4 T cells (data not shown). Moreover, when TCRβ−/− mice that received 1′ CD25neg CD4 T cells were treated with anti-CD25 (PC61) or control Ab at the time of 2′ naïve CD4 T cell transfer, the proliferation of newly transferred naïve CD4 T cells was efficiently inhibited by the 1′ memory CD4 T cells regardless of PC61 Ab treatment (data not shown), strongly suggesting that inducible Tregs (iTreg) which might have been generated from the 1′ transfer do not appear to be involved in the inhibition process.

Selective expression of IL-27 in CD8+ DC subsets suggests that the capacity of DC to stimulate naïve T cell proliferation via a homeostatic mechanism might be divergent depending on the subsets (15, 49). In fact, it was demonstrated that CD8+ DC result in reduced proliferative T cell responses, when compared to CD8− DC (50), which is possibly mediated by IL-27. This mode of regulation under non-inflammatory settings could be important and efficient in preventing unnecessary activation of naïve T cells during homeostatic control (23), consistent with the idea that CD8+ DC are primarily involved in peripheral tolerance (28).

There are some outstanding questions that need further investigation. We previously reported that TCR repertoire diversity is critical in regulating naïve T cell homeostasis because memory T cells with single or limited specificity were unable to inhibit naïve cell proliferation while those cells with highly diverse specificity were fully capable of doing so (12). Thus, memory CD4 T cell interaction with DC and subsequent induction of IL-27 may be affected by the TCR repertoire complexity. It will be critical to understand how memory T cell repertoire complexity regulates DC production of IL-27. Moreover, in this study, we mainly studied homeostatic mechanism controlled by memory CD4 T cells. Whether memory CD8 T cells exert similar regulatory mechanisms, and if so, whether IL-27 is also involved in the process needs to be tested.

In summary, homeostatic regulation of T cell proliferation is achieved by multiple mechanisms. IL-27 is mainly involved in limiting naïve T cell proliferation without exogenous Ag, while IL-7 might be primarily involved in regulating the overall size as well as the survival of the peripheral T cells. Concerted action between two cytokines and between different T cell subsets and DC is likely to contribute to T cell homeostasis. As dysregulated DC functions are likely to be associated with uncontrolled activation of T cells (51), controlling DC functions and naïve T cell responses by memory CD4 T cells may represent a novel mechanism by which the immune system achieves a homeostatic balance in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank the Amgen for providing IL-27R-deficient mice, Ms. Jennifer Powers for cell sorting, and Dr. William E. Paul for critical review of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the NIH grant AI074932 (B.M.).

Footnotes

Competing interests statement The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Boyman O, Letourneau S, Krieg C, Sprent J. Homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive and memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2088–2094. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams KM, Hakim FT, Gress RE. T cell immune reconstitution following lymphodepletion. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanchot C, Rosado MM, Agenes F, Freitas AA, Rocha B. Lymphocyte homeostasis. Semin Immunol. 1997;9:331–337. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kieper WC, Troy A, Burghardt JT, Ramsey C, Lee JY, Jiang HQ, Dummer W, Shen H, Cebra JJ, Surh CD. Recent immune status determines the source of antigens that drive homeostatic T cell expansion. J Immunol. 2005;174:3158–3163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prlic M, Jameson SC. Homeostatic expansion versus antigen-driven proliferation: common ends by different means? Microbes Infect. 2002;4:531–537. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst B, Lee DS, Chang JM, Sprent J, Surh CD. The peptide ligands mediating positive selection in the thymus control T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation in the periphery. Immunity. 1999;11:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stefanova I, Dorfman JR, Germain RN. Self-recognition promotes the foreign antigen sensitivity of naive T lymphocytes. Nature. 2002;420:429–434. doi: 10.1038/nature01146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min B, Yamane H, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. Spontaneous and homeostatic proliferation of CD4 T cells are regulated by different mechanisms. J Immunol. 2005;174:6039–6044. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datta S, Sarvetnick N. Lymphocyte proliferation in immune-mediated diseases. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupica T, Jr., Fry TJ, Mackall CL. Autoimmunity during lymphopenia: a two-hit model. Clin Immunol. 2006;120:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.04.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge Q, Hu H, Eisen HN, Chen J. Different contributions of thymopoiesis and homeostasis-driven proliferation to the reconstitution of naive and memory T cell compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2989–2994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052714099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min B, Foucras G, Meier-Schellersheim M, Paul WE. Spontaneous proliferation, a response of naive CD4 T cells determined by the diversity of the memory cell repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3874–3879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400606101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winstead CJ, Reilly CS, Moon JJ, Jenkins MK, Hamilton SE, Jameson SC, Way SS, Khoruts A. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells optimize diversity of the conventional T cell repertoire during reconstitution from lymphopenia. J Immunol. 2010;184:4749–4760. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandjean I, Duban L, Bonney EA, Corcuff E, Di Santo JP, Matzinger P, Lantz O. Are major histocompatibility complex molecules involved in the survival of naive CD4+ T cells? J Exp Med. 2003;198:1089–1102. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Do JS, Min B. Differential requirements of MHC and of DCs for endogenous proliferation of different T-cell subsets in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20394–20398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909954106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilarregui JM, Croci DO, Bianco GA, Toscano MA, Salatino M, Vermeulen ME, Geffner JR, Rabinovich GA. Tolerogenic signals delivered by dendritic cells to T cells through a galectin-1-driven immunoregulatory circuit involving interleukin 27 and interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:981–991. doi: 10.1038/ni.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diveu C, McGeachy MJ, Boniface K, Stumhofer JS, Sathe M, Joyce-Shaikh B, Chen Y, Tato CM, McClanahan TK, de Waal Malefyt R, Hunter CA, Cua DJ, Kastelein RA. IL-27 blocks RORc expression to inhibit lineage commitment of Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5748–5756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald DC, Zhang GX, El-Behi M, Fonseca-Kelly Z, Li H, Yu S, Saris CJ, Gran B, Ciric B, Rostami A. Suppression of autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system by interleukin 10 secreted by interleukin 27-stimulated T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1372–1379. doi: 10.1038/ni1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villarino AV, Stumhofer JS, Saris CJ, Kastelein RA, de Sauvage FJ, Hunter CA. IL-27 limits IL-2 production during Th1 differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;176:237–247. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida H, Hamano S, Senaldi G, Covey T, Faggioni R, Mu S, Xia M, Wakeham AC, Nishina H, Potter J, Saris CJ, Mak TW. WSX-1 is required for the initiation of Th1 responses and resistance to L. major infection. Immunity. 2001;15:569–578. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owaki T, Asakawa M, Kamiya S, Takeda K, Fukai F, Mizuguchi J, Yoshimoto T. IL-27 suppresses CD28-mediated [correction of medicated] IL-2 production through suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J Immunol. 2006;176:2773–2780. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winstead CJ, Reilly CS, Moon JJ, Jenkins MK, Hamilton SE, Jameson SC, Way SS, Khoruts A. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells Optimize Diversity of the Conventional T Cell Repertoire during Reconstitution from Lymphopenia. J Immunol. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Min B, Paul WE. Endogenous proliferation: burst-like CD4 T cell proliferation in lymphopenic settings. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kedl RM, Schaefer BC, Kappler JW, Marrack P. T cells down-modulate peptide-MHC complexes on APCs in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:27–32. doi: 10.1038/ni742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bevan MJ. In a radiation chimaera, host H-2 antigens determine immune responsiveness of donor cytotoxic cells. Nature. 1977;269:417–418. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Z, Bensinger SJ, Zhang J, Chen C, Yuan X, Huang X, Markmann JF, Kassaee A, Rosengard BR, Hancock WW, Sayegh MH, Turka LA. Homeostatic proliferation is a barrier to transplantation tolerance. Nat Med. 2004;10:87–92. doi: 10.1038/nm965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stumhofer JS, Hunter CA. Advances in understanding the anti-inflammatory properties of IL-27. Immunol Lett. 2008;117:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shortman K, Heath WR. The CD8+ dendritic cell subset. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:18–31. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murugaiyan G, Mittal A, Weiner HL. Identification of an IL-27/osteopontin axis in dendritic cells and its modulation by IFN-gamma limits IL-17-mediated autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11495–11500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002099107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scharton TM, Scott P. Natural killer cells are a source of interferon gamma that drives differentiation of CD4+ T cell subsets and induces early resistance to Leishmania major in mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:567–577. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stumhofer JS, Laurence A, Wilson EH, Huang E, Tato CM, Johnson LM, Villarino AV, Huang Q, Yoshimura A, Sehy D, Saris CJ, O’Shea JJ, Hennighausen L, Ernst M, Hunter CA. Interleukin 27 negatively regulates the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells during chronic inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:937–945. doi: 10.1038/ni1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batten M, Li J, Yi S, Kljavin NM, Danilenko DM, Lucas S, Lee J, de Sauvage FJ, Ghilardi N. Interleukin 27 limits autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing the development of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:929–936. doi: 10.1038/ni1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox JH, Kljavin NM, Ramamoorthi N, Diehl L, Batten M, Ghilardi N. IL-27 promotes T cell-dependent colitis through multiple mechanisms. J Exp Med. 2011;208:115–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li WQ, Jiang Q, Aleem E, Kaldis P, Khaled AR, Durum SK. IL-7 promotes T cell proliferation through destabilization of p27Kip1. J Exp Med. 2006;203:573–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzucchelli RI, Warming S, Lawrence SM, Ishii M, Abshari M, Washington AV, Feigenbaum L, Warner AC, Sims DJ, Li WQ, Hixon JA, Gray DH, Rich BE, Morrow M, Anver MR, Cherry J, Naf D, Sternberg LR, McVicar DW, Farr AG, Germain RN, Rogers K, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Durum SK. Visualization and identification of IL-7 producing cells in reporter mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fry TJ, Mackall CL. The many faces of IL-7: from lymphopoiesis to peripheral T cell maintenance. J Immunol. 2005;174:6571–6576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guimond M, Veenstra RG, Grindler DJ, Zhang H, Cui Y, Murphy RD, Kim SY, Na R, Hennighausen L, Kurtulus S, Erman B, Matzinger P, Merchant MS, Mackall CL. Interleukin 7 signaling in dendritic cells regulates the homeostatic proliferation and niche size of CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:149–157. doi: 10.1038/ni.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fry TJ, Mackall CL. Interleukin-7: master regulator of peripheral T-cell homeostasis? Trends Immunol. 2001;22:564–571. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–478. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alpan O, Bachelder E, Isil E, Arnheiter H, Matzinger P. ‘Educated’ dendritic cells act as messengers from memory to naive T helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:615–622. doi: 10.1038/ni1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wirtz S, Becker C, Fantini MC, Nieuwenhuis EE, Tubbe I, Galle PR, Schild HJ, Birkenbach M, Blumberg RS, Neurath MF. EBV-induced gene 3 transcription is induced by TLR signaling in primary dendritic cells via NF-kappa B activation. J Immunol. 2005;174:2814–2824. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molle C, Nguyen M, Flamand V, Renneson J, Trottein F, De Wit D, Willems F, Goldman M, Goriely S. IL-27 synthesis induced by TLR ligation critically depends on IFN regulatory factor 3. J Immunol. 2007;178:7607–7615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J, Guan X, Ma X. Regulation of IL-27 p28 gene expression in macrophages through MyD88- and interferon-gamma-mediated pathways. J Exp Med. 2007;204:141–152. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villarino A, Hibbert L, Lieberman L, Wilson E, Mak T, Yoshida H, Kastelein RA, Saris C, Hunter CA. The IL-27R (WSX-1) is required to suppress T cell hyperactivity during infection. Immunity. 2003;19:645–655. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu CR, Mahdi RM, Ebong S, Vistica BP, Gery I, Egwuagu CE. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 regulates proliferation and activation of T-helper cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29752–29759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pot C, Apetoh L, Awasthi A, Kuchroo VK. Molecular pathways in the induction of interleukin-27-driven regulatory type 1 cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2010;30:381–388. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perona-Wright G, Mohrs K, Mohrs M. Sustained signaling by canonical helper T cell cytokines throughout the reactive lymph node. Nat Immunol. 11:520–526. doi: 10.1038/ni.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feau S, Arens R, Togher S, Schoenberger SP. Autocrine IL-2 is required for secondary population expansion of CD8(+) memory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:908–913. doi: 10.1038/ni.2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suffner J, Hochweller K, Kuhnle MC, Li X, Kroczek RA, Garbi N, Hammerling GJ. Dendritic cells support homeostatic expansion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in Foxp3.LuciDTR mice. J Immunol. 184:1810–1820. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kronin V, Winkel K, Suss G, Kelso A, Heath W, Kirberg J, von Boehmer H, Shortman K. A subclass of dendritic cells regulates the response of naive CD8 T cells by limiting their IL-2 production. J Immunol. 1996;157:3819–3827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen M, Wang YH, Wang Y, Huang L, Sandoval H, Liu YJ, Wang J. Dendritic cell apoptosis in the maintenance of immune tolerance. Science. 2006;311:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1122545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.