Abstract

Conjugated dienes can be diaminated at the internal and/or terminal double bonds using Cu(I) as catalyst and N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) as nitrogen source. The regioselectivity is highly dependent upon the choice of Cu(I) catalyst and the substituents on diene substrates. The diamination likely proceeds via two mechanistically distinct pathways. The N-N bond of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) is first homolytically cleaved by the Cu(I) catalyst to form four-membered Cu(III) species A and Cu(II) radical species B, which are in rapid equilibrium. The internal diamination likely proceeds in a concerted manner via Cu(III) species A and the terminal diamination likely involves Cu(II) radical species B. Kinetic studies have shown that the diamination is first-order in N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1), zero-order in olefin, first-order in total Cu(I) catalyst, and the cleavage of the N-N bond of 1 by the Cu(I) catalyst is the rate-determining step. The internal diamination is favored by use of CuBr without ligand and electron-rich dienes. The terminal diamination is favored when using CuCl-L and dienes with radical-stabilizing groups.

Introduction

1,2-Diamines are important functional moieties present in many biologically active compounds and chiral catalysts.1 The synthesis of 1,2-diamines is of interest to organic chemists.1 Diamination of olefins, allowing direct installation of two nitrogen atoms across C-C double bonds, provides a straightforward approach to prepare 1,2-diamines. Various metal-free,1,2 metal-mediated,1,3,4 and metal-catalyzed4c,5-8 diaminations of olefins have been developed. In our own studies, we have developed Pd(0)-9,10,11 and Cu(I)-catalyzed12-15 diaminations of olefins using three-membered rings 1-316-19 as nitrogen sources (Chart 1). When Pd(0) was used as catalyst, various dienes were efficiently diaminated at the internal double bonds with N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (Scheme 1).9 Mechanistic studies suggest this diamination likely proceeds via a concerted reaction pathway.9f The Pd(0) catalyst inserts into the N-N bond of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) to form four-membered Pd(II) species 6,20 which reacts with diene 4 to give π-allyl Pd species 7.21,22 Species 7 then undergoes reductive elimination to give internal diamination product 5 and regenerate the Pd(0) catalyst.23 However, when CuCl-L complex was used as catalyst, the terminal diamination product 8 was predominantly formed for various conjugated dienes (Scheme 2).12a A radical mechanism has been proposed for this Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination.12a The Cu(I) first homolytically cleaves the N-N bond of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) to give nitrogen radical species 9.24-28 Radical species 9 adds to the terminal double bond of the diene to form allyl radical species 10, which then undergoes rapid C-N bond formation to give terminal diamination product 8 and regenerate the Cu(I) catalyst. The CuCl-L catalyzed diamination with N,N-di-t-butylthiadiaziridine 1,1-dioxide (2)14 and N,N-di-t-butyl-3-(cyanimino) diaziridine (3)15 also appears to proceed via a stepwise radical mechanism based upon studies of deuterated olefin substrates.

Chart 1.

Scheme 1.

Pd(0)-catalyzed internal diamination of dienes

Scheme 2.

Cu(I)-catalyzed terminal diamination of dienes

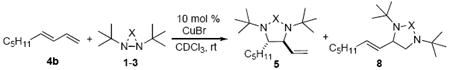

Very recently, we have found that various conjugated dienes can be predominantly diaminated at internal double bonds when CuBr without ligand is used as catalyst, giving internal diamination product 5 in good yield and high regioselectivity (Scheme 3).29 The preliminary studies suggest that the Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination may proceed via two distinct pathways (Scheme 4). The terminal diamination proceeds via a stepwise radical mechanism involving Cu(II)30 intermediate (B) and the internal diamination proceeds via a concerted mechanism involving a four-membered Cu(III)31,32 species (A) similar to that of the Pd(0)-catalyzed diamination.9f To better understand the Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination,33,34 we have further investigated this reaction including kinetics, substituent effect, and the effect of different nitrogen sources. Herein, we wish to report our detailed studies on this subject.

Scheme 3.

Cu(I)-catalyzed regioselective diamination of dienes

Scheme 4.

Proposed mechanisms for the Cu(I)-catalyzed regioselective diamination of conjugated dienes

Results and Discussion

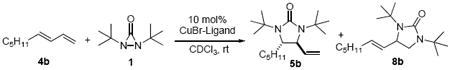

Various conjugated dienes have been investigated for the internal diamination using CuBr29a and/or terminal diamination using CuCl-PCy3. As shown in Table 1, 1-monosubstituted (entries 1, 3, and 4), 1,2-disubstituted (entries 7, 8, 10-14), 1,3-disubstituted (entries 15-18), and 1,2,3-trisubstituted (entries 20 and 21) dienes can be efficiently diaminated at the internal double bonds with 5-10 mol % CuBr and N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1), giving diamination products 5 in good yields and high regioselectivities. 1-Arylbutadienes such as (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene exhibited relatively low regioselectivity for internal diamination using CuBr (Table 1, entry 5), but high regioselectivity for terminal diamination using CuCl-PCy3 (Table 1, entry 6).35 However, the regioselectivity for the internal diamination using CuBr increased dramatically when additional alkyl substituent(s) were introduced at the 2 and/or 3 positions (Table 1, entries 8, 18, and 21) of the diene substrates. For 1-alkylbutadiene substrates, high regioselectivity can be obtained for either internal diamination using CuBr or terminal diamination using CuCl-PCy3 (Table 1, entries 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Cu(I)-catalyzed regioselective diamination of dienesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | method | product | yield (%)b (5:8)c |

| 1 |

|

A |

|

99 |

| 2 | B |

|

53 (3:97) | |

| 3 |

|

A |

|

97 (96:4) |

| 4 |

|

A |

|

95 |

| 5 |

|

A |

|

90 (27:73) |

| 6 | B |

|

75 | |

| 7 |

|

A |

|

81 |

| 8 |

|

A |

|

92 (97:3) |

| 9 | B |

|

94 | |

| 10 |

|

A |

|

95 |

| 11 | 4h, n = 2 | 99 | ||

| 12 | 4i, n = 3 | 94 | ||

| 13 |

|

A |

|

85 |

| 14 |

|

A |

|

95 (97:3)d |

| 15 |

|

A |

|

98 |

| 16 |

|

A |

|

96 (89:11) |

| 17 |

|

A |

|

94 |

| 18 |

|

A |

|

97 (91:9) |

| 19 | B |

|

99 | |

| 20 |

|

A |

|

90 |

| 21 |

|

A |

|

95 |

Method A (taken from ref. 29a): All reactions were carried out with olefin 4 (0.20 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.22 mmol), CuBr (0.010 mmol) in CDCl3 (0.4 mL) under Ar with vigorous stirring at 0 °C for 20 h unless otherwise stated. For entry 3, olefin 4b (0.19 mmol) was used. For entry 4, olefin 4c (0.25 mmol, E:Z = 15.7:1, E isomer: 0.24 mmol) and 1 (0.20 mmol) were used. For entry 5, the reaction was carried out with 1 (0.24 mmol), CuBr (0.020 mmol), and CDCl3 (0.8 mL) for 24 h. For entry 12, the reaction was carried out on 0.40 mmol scale. For entry 14, CuBr (0.020 mmol) was used. For entry 18, the reaction was carried out in CDCl3 (1 mL) at -20 °C for 40 h. Method B: All reactions were carried out with olefin 4 (0.20 mmol), 1 (0.40 mmol), CuCl-PCy3 (1:1.5) [0.020 mmol, prepared in situ from CuCl (0.020 mmol) and PCy3 (0.030 mmol) in C6D6 (0.20 mL) by stirring at room temperature for 1 h] in C6D6 (0.25 mL) under Ar at room temperature for 10 h unless otherwise stated. Entries 2 and 19 were taken from ref. 29a. For entries 2 and 9, the reactions were carried out with olefin 4 (2.0 mmol) and 1 [0.20 mmol, dissolved in C6D6 (0.1 mL), slow addition over 7 h] at room temperature for 10 h (total).

Isolated yield based on 4 except entries 2, 4, and 9 which were based on 1.

The ratio was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. The ratio of 5/8 is >99:1 unless otherwise indicated. For entries 6, 9, 19, the ratio of 8/5 is >99:1.

The stereochemistry was tentatively assigned on the basis of sterics.

1. Kinetic Model and Analysis of the Cu(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective Diamination

Based on the mechanisms proposed in Scheme 4, a kinetic model has been established for the Cu(I)-catalyzed regioselective diamination (for the detailed derivation, see Supporting Information). Using steady-state approximation, the internal diamination rate and the terminal diamination rate are expressed as equations 1 and 2, respectively. The ratio of internal diamination product 5 to terminal diamination product 8 can be expressed as equation 3, indicating that the diamination regioselectivity is dependent on the equilibrium between A and B (K), the equilibrium between A and D (k2/k-2), and the rate constants of C-N bond formation (k3 and k5).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

2. Kinetic Studies

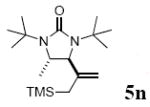

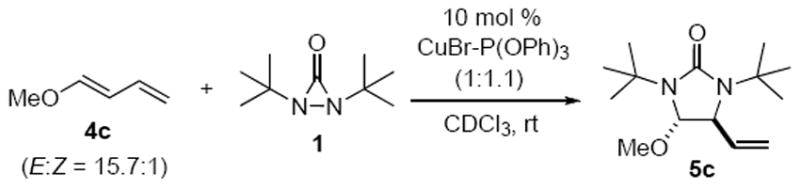

The proposed diamination mechanism in Scheme 4 involves the cleavage of the N-N bond of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) by the Cu(I) catalyst and the subsequent C-N formation with diene 4. In order to determine the rate-determining step for the reaction, kinetic studies were carried out using 1-methoxy-1,3-butadiene (4c) as substrate for internal diamination (Scheme 5) and (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene (4d) as substrate for terminal diamination (Scheme 6). The reactions were monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy using Si(SiMe3)4 as internal standard. The concentrations of diaziridinone 1, internal diamination product 5c, and terminal diamination product 8d were calculated by integration of the signals corresponding to their respective t-butyl groups. As judged by 1H NMR spectroscopy, internal diamination product 5c and terminal diamination product 8d were formed with high regioselectivities using 10 mol % CuBr-P(OPh)3 and 10 mol % CuCl-P(OPh)3 as catalysts, respectively.

Scheme 5.

Scheme 6.

(a) Reaction Order in N,N-Di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1)

1-Methoxy-1,3-butadiene (4c) was chosen as test substrate for the kinetic studies of internal diamination due to its high reactivity and high regioselectivity for internal diamination. CuBr-P(OPh)3 (1:1.1) was used as catalyst instead of CuBr (Table 1, Method A) for the kinetic study because it was soluble in CDCl3 and also gave the internal diamination product for 4c. The reaction was carried out in an NMR tube at room temperature (Scheme 5). Internal diamination product 5c was cleanly formed during the reaction as judged by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. No terminal diamination product and negligible amounts of by-products from the decomposition of 1 were observed. Since the internal diamination predominates in this case, equation 1 can be simplified to equation 4 (for detailed derivation, see Supporting Information). Equation 4 can be further expressed as equation 5 if the cleavage of the N-N bond of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) by the Cu(I) catalyst is the rate-determining step (for detailed derivation, see Supporting Information). The plot of ln([1]0/[1]) against reaction time gave a straight line with kobs = 2.3 × 10-3 s-1 (Figure 1), indicating first-order dependence on diaziridinone 1 in the internal diamination of 1-methoxy-1,3-butadiene (4c), which is consistent with the rate law shown in equation 5.

| (4) |

| (5) |

Figure 1.

Plot of ln([1]0/[1]) against reaction time (min) for the Cu(I)-catalyzed internal diamination of 1-methoxy-1,3-butadiene (4c) (E:Z = 15.7:1, E isomer: 0.24 mmol) with 1 (0.20 mmol) and CuBr-P(OPh)3 (1:1.1) (0.020 mmol) in CDCl3 (total solution volume: 1.2 mL) in an NMR tube at room temperature. [1]0 stands for the initial concentration of 1 in M and [1] stands for the concentration of 1 in M at a particular time.

The diamination of 1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene (4d) with 10 mol % CuCl-P(OPh)3 and 1 occurred regioselectively at the terminal double bond as judged by the 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture. CuCl-P(OPh)3 was chosen as catalyst instead of CuCl-PCy3 (Table 1, method B) for the kinetic study because the 1H NMR signal of P(OPh)3 does not interfere with the signals of the tert-butyl groups of 1 and 8d as PCy3 does. Equation 2 can be similarly simplified to equation 6 if the cleavage of the N-N of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) is also assumed to be the rate-determining step. The straight line obtained for the plot of ln([1]0/[1]) against reaction time with kobs = 3.0 × 10-3 s-1 (Figure 2) also indicates first-order kinetics in N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) in this case.

| (6) |

Figure 2.

Plot of ln([1]0/[1]) against reaction time (min) for the Cu(I)-catalyzed terminal diamination of (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene (4d) (0.72 mmol) with 1 (0.20 mmol) and CuCl-P(OPh)3 (1:1.5) (0.020 mmol) in dry C6D6 (total solution volume: 1.2 mL) in an NMR tube at room temperature. [1]0 stands for the initial concentration of 1 in M and [1] stands for the concentration of 1 in M at a particular time.

The decomposition of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) was investigated using CuBr-P(OPh)3 (1:4) complex as catalyst in the absence of a diene substrate (Scheme 7). The reaction was carried out in CDCl3 and monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) rapidly decomposed to unidentified compounds (Figure 3). Under the reaction conditions, Cu species A or B cannot be detected by NMR spectroscopy even with stoichiometric amounts of Cu(I) salt at low temperature, which indicates the decomposition of A and B should be faster than their formation. Under the diamination conditions, the reaction between A and B with the diene substrate should be even faster than the decomposition of A and B, which also suggests the formation of A and B is likely to be the rate-determining step.

Scheme 7.

Figure 3.

Plot of [1] against reaction time (min) in the Cu(I)-catalyzed decomposition of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.20 mmol) with CuBr-P(OPh)3 (1:4.0) (0.020 mmol) in CDCl3 (total solution volume: 1.2 mL) in an NMR tube at room temperature.

(b) Effect of Olefin Concentration

According to equations 5 and 6 the internal and terminal diamination reactions should be zero-order in olefin 4. The effect of olefin concentration on the internal and the terminal diaminations was investigated using 1-methoxy-1,3-butadiene (4c) and (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene (4d), respectively. Similar reaction rates were observed for the CuBr-catalyzed internal diamination when [4c]0 varied from 0.067 to 0.40 M (Figure 4). The slightly reduced reaction rate observed with high [4c]0 (0.67 M) is possibly due to the complexation of the Cu catalyst with the diene substrate. For the CuCl-catalyzed terminal diamination of (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene (4d), similar reaction rates were also observed when [4d]0 varied from 0.10 to 0.60 M (Figure 5). These results indicate that the potential involvement of copper-diene complexes has little affect on the overall kinetic profile, and the concentration of diene 4c or 4d has negligible influence on the rate of diamination, which is consistent with the rate law as expressed in equations 5 and 6. The fact that the diamination is first-order in N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (Figures 1 and 2) and zero-order in diene 4 (Figures 4 and 5) further indicates that the cleavage of the N-N bond of 1 by the Cu(I) complex to form active Cu species A and B is the rate-determining step of the diamination.

Figure 4.

Plots of [5c] (M) against reaction time (min) for the Cu(I)-catalyzed internal diamination of 1-methoxy-1,3-butadiene (4c) with variable initial olefin concentrations. The diaminations were carried out with 4c (E:Z = 15.7:1, E isomer: 0.080 mmol, 0.16 mmol, 0.24 mmol, 0.48 mmol, or 0.80 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.20 mmol), and CuBr-P(OPh)3 (1:1.1) (0.020 mmol) in CDCl3 (total solution volume: 1.2 mL) in an NMR tube at room temperature.

Figure 5.

Plots of [8d] (M) against reaction time (min) for the Cu(I)-catalyzed terminal diamination of (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene (4d) with variable initial olefin concentrations. The diaminations were carried out with 4d (0.12 mmol, 0.24 mmol, 0.48 mmol, or 0.72 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.20 mmol), and CuCl-P(OPh)3 (1:1.5) (0.020 mmol) in C6D6 (total solution volume: 1.2 mL) in an NMR tube at room temperature.

(c) Effect of Total Cu Concentration

According to equations 5 and 6, the internal and terminal diaminations should be first-order in total Cu catalyst concentration. CuBr-catalyzed internal diamination of 1-methoxy-1,3-butadiene (4c) and CuCl-catalyzed terminal diamination of (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene (4d) were then investigated with variable amounts of initial Cu salts. The plots of kobs against total Cu catalysts ([CuBr]0 and [CuCl]0) have found to be straight lines as shown in Figure 6 for the internal diamination of 4c, and in Figure 7 for the terminal diamination of 4d. This data indicates that the internal and terminal diaminations are first-order in total Cu catalyst as expressed in equations 5 and 6.

Figure 6.

Plot of kobs against [CuBr]0 for the Cu(I)-catalyzed internal diamination of 1-methoxy-1,3-butadiene (4c) with variable amounts of total CuBr (0.020-0.10 mmol). The diaminations were carried out with 4c (E:Z = 15.7:1, E isomer: 0.24 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.20 mmol), and CuBr-P(OPh)3 (1:1.1) (0.020 mmol, 0.040 mmol, 0.060 mmol, 0.080 mmol, and 0.10 mmol) in CDCl3 (total solution volume: 1.2 mL) in an NMR tube at room temperature.

Figure 7.

Plot of kobs against [CuCl]0 for the Cu(I)-catalyzed terminal diamination of (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene (4d) with variable amounts of total CuCl (0.020-0.10 mmol). The diaminations were carried out with 4d (0.24 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.20 mmol), and CuCl-P(OPh)3 (1:1.5) (0.020 mmol, 0.040 mmol, 0.060 mmol, 0.080 mmol, and 0.10 mmol) in C6D6 (total solution volume: 1.2 mL) in an NMR tube at room temperature.

3. EPR Studies

Intermediates A and B are proposed to be involved in the Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination with N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (Scheme 4). However, these intermediates could not be detected by the NMR spectroscopy. Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) was subsequently used to detect any radical species. A triplet with a 1:1:1 intensity ratio was observed when N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) was treated with CuCl-P(OPh)3 (1:1.5) at low temperature (Figure 8), which supports the existence of nitrogen radical intermediate B.

Figure 8.

EPR spectrum for the reaction between N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.050 mmol) and CuCl-P(OPh)3 (1:1.5) (0.0050 mmol) in toluene (0.18 mL) at -50 °C. A similar triplet was also observed when the reaction was performed in the presence of (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadiene 4d (0.10 mmol).

4. Effect of Copper Salt and Ligand

The effect of copper salt on the diamination was investigated in C6D6 using (E)-nona-1,3-diene (4b) as substrate (Table 2). CuCl and CuBr exhibited the highest catalytic activity for the diamination (Table 2, entries 1 and 2). CuBr gave the highest regioselectivity for the internal diamination (Table 2, entry 2). Interestingly, CuCN gave only terminal diamination product with moderate catalytic activity (Table 2, entry 5). Apparently, the counter anion of the Cu(I) salt has a dramatic effect on the reactivity and selectivity for the diamination. The counter anion could affect the reaction by altering the relative stability and/or reactivity of four-membered Cu(III) species A and Cu(II) radical species B.

Table 2.

Studies of the effect of copper salt on the diamination of (E)-nona-1,3-diene (4b)a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | conv. (%)b | 5b : 8bc |

| 1 | CuCl-P(OPh)3 | 60 | 0.37 : 1 |

| 2 | CuBr-P(OPh)3 | 69 | 1.26 : 1 |

| 3 | CuI-P(OPh)3 | 29 | 0.11 : 1 |

| 4 | CuOAc-P(OPh)3 | 0 | |

| 5 | CuCN-P(OPh)3 | 50 | 0 : 1 |

| 6 | CuSPh-P(OPh)3 | 0 | |

The diamination was carried out with diene 4b (0.20 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.30 mmol), and CuX-P(OPh)3 (1:1.5) (0.020 mmol) in C6D6 (0.20 mL) in a 1.5 mL vial at room temperature under Ar for 10 h unless otherwise stated.

The conversion was based on diene 4b and determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

The ratio of 5b to 8b was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture except for Entry 3. For Entry 3, an accurate ratio of 5b to 8b was difficult to obtain by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture due to the signal interference with baseline noise and unknown byproducts. The ratio was thus obtained by 1H NMR analysis after flash chromatography (5b and 8b were nearly inseparable by column).

Various ligands were also investigated for the Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination of (E)-nona-1,3-diene (4b) (Table 3). Bidentate phosphine, such as BINAP was found to be an ineffective ligand for the diamination (Table 3, entry 1). Monodentate ligands exhibited good activity for the reaction (Table 3, entries 2-8). The regioselectivity was also greatly influenced by the ligand. It appears that electron-rich ligands such as tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine and tricyclohexylphosphine favored terminal diamination (Table 3, entries 3 and 5), whereas electron-deficient ligands such as tris(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)phosphine favored internal diamination (Table 3, entry 4). The Cu-ligand ratio was also investigated. Increasing the amount of ligand lowered the regioselectivity for internal diamination product (Table 3, entries 6-8). CuBr without ligand gave the highest regioselectivity for internal diamination (Table 3, entry 9). The ligand could influence the relative amount and/or reactivity of four-membered Cu(III) species A and Cu(II) radical species B, consequently affecting the regioselectivity of the diamination. Coordination of a ligand (particularly a bulky ligand such as PCy3) to the Cu could increase the steric congestion around the Cu and cause the equilibrium to shift toward the sterically less crowded Cu(II) radical species B, favoring terminal diamination. At the same time, coordination of a ligand to the Cu could disfavor the formation of complex D and subsequent internal diamination.

Table 3.

Studies of the ligand effect on the Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination of (E)-nona-1,3-diene (4b)a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Ligand (L:Cu) | conv. (%)b | 5b : 8bc |

| 1 | (±)-BINAP(1.5 :1) | 0 | |

| 2 | PPh3 (1.5 :1) | 72 | 0.76 : 1 |

| 3 | P(4-MeOPh)3 (1.5 :1) | 60 | 0.35 : 1 |

| 4 | P(4-CF3PPh)3 (1.5 :1) | 92 | 1.59 : 1 |

| 5 | P(cyclohexyl)3 (1.5 :1) | 77 | 0.33 : 1 |

| 6 | P(OPh)3 (1:1) | 99 | 2.9 : 1 |

| 7 | P(OPh)3 (1.5 :1) | 94 | 1.89 : 1 |

| 8 | P(OPh)3 (4 :1) | 87 | 0.92 : 1 |

| 9 | No ligand | 99 | 10 : 1 |

The diaminations were carried out with diene 4b (0.20 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.30 mmol), and CuBr-ligand (0.020 mmol) in CDCl3 (0.2 mL) in a 1.5 mL vial at room temperature under Ar for 10 h.

The conversion was based on diene 4b and determined by analysis of the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude reaction mixture.

The ratio of 5b to 8b was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

5. Substituent Effect

The diamination of various para-substituted (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadienes was carried out using CuCl-P(OPh)3 (1:1.5) in C6D6. Under these reaction conditions, the diamination occurred essentially only at the terminal double bond as judged by 1H NMR spectroscopy. As shown in Table 4, the diamination was accelerated by both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents (Table 4, entries 1, 2, 4-6 vs entry 3). The Hammett plot of log(kX/kH) against radical substituent constant σ• for the reaction gave a straight line as shown in Figure 9,36,37 which is consistent with the radical mechanism proposed for the terminal diamination as shown in Scheme 4 [for the Hammett plot of log(kX/kH) against σp, see: Figure 9a in Supporting Information].

Table 4.

Competition experiments of CuCl-catalyzed terminal diamination of para-substituted (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadienes 4a

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | arylbutadiene (4) | ratio of [8]x/[8]Hb |

| 1 | X = Me, 4r | 1.18 |

| 2 | X = Ph, 4s | 1.33 |

| 3 | X = H, 4d | 1.00 |

| 4 | X = Cl, 4t | 1.13 |

| 5 | X = Br, 4u | 1.08 |

| 6 | X = NO2, 4v | 1.55 |

The competitive diaminations were carried out with 4d (1.0 mmol), competing diene (4r, 4s, 4t, 4u, or 4v) (1.0 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.10 mmol), and CuCl-P(OPh)3 (1:1.5) (0.020 mmol) in C6D6 (1.0 mL) in a 3.0 mL vial under Ar at room temperature for 6 h.

The ratio of [8]x/[8]H was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

Figure 9.

Plot of log(kX/kH) against radical substituent constant σ• for the CuCl-catalyzed terminal diamination of para-substituted (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadienes 4. The radical substituent constants σ• were taken from ref. 36b.

The diamination of para-substituted (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadienes was also carried out with 10 mol % CuBr as catalyst. Under these reaction conditions, a mixture of internal and terminal diamination products (5 and 8) was formed. As shown in Table 5, in all these cases the terminal diamination product (8) was the major product. However, the relative amount of internal diamination product increased with the electron-donating capability of the substituents. A good correlation was obtained in the Hammett plot of the regioselectivity ([5]/[8]) against 0.23σ• + 0.77σp (Figure 10) using the best-fit approach (for the Hammett plots of the regioselectivity against σ• and σp, see: Figures 10a and 10b in Supporting Information).36-38 The regioselectivity of the diamination appears to be more sensitive to substituent constant σp (77%) than to radical-based substituent constant σ•. The negative slope suggests that radical-stabilizing and electron-withdrawing substituents decrease the ratio of internal to terminal diamination ([5]/[8]), and that the internal diamination of diene 4 with Cu(III) species A (Scheme 4) is likely to be electrophilic in nature.

Table 5.

Ratio of [5]/[8] for the CuBr-catalyzed diamination of para-substituted (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadienes 4a

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | arylbutadiene (4) | [5]/[8] b |

| 1 | X = OMe, 4w | 0.94 |

| 2 | X = Me, 4r | 0.80 |

| 3 | X = Ph, 4s | 0.29 |

| 4 | X = H, 4d | 0.37 |

| 5 | X = F, 4x | 0.37 |

| 6 | X = Cl, 4t | 0.21 |

| 7 | X = Br, 4u | 0.18 |

The diamination was carried out with diene 4 (0.20 mmol), N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) (0.24 mmol), and CuBr (0.020 mmol) in CDCl3 (0.80 mL) in a 1.5 mL vial at 0 °C under Ar for 24 h.

The ratio of [5]/[8] was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

Figure 10.

Hammett correlation of regioselectivity ([5]/[8]) for the CuBr-catalyzed diamination of para-substituted (E)-1-phenyl-1,3-butadienes 4. The radical substituent constants σ• were taken from ref. 36b and the substituent constants σp were taken from ref. 38.

6. Effect of Nitrogen Source

The diamination of (E)-nona-1,3-diene (4b) was investigated with 10 mol % CuBr as catalyst using different nitrogen sources (1, 2, and 3). These three nitrogen sources displayed very different regioselectivity in the diamination reaction. While N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) gave high regioselectivity favoring internal diamination (Table 6, entry 1), N,N-di-t-butyl-3-(cyanimino)-diaziridine (3) afforded essentially only the terminal diamination product (Table 6, entry 3). The high regioselectivity for terminal diamination exhibited by 3 is likely due to the fact that the CN group can stabilize the radical Cu(II) species G, thus steering the reaction toward the terminal diamination (Scheme 8). At the same time, higher content of radical species G likely leads to more rapid decomposition of 3 via the radical pathway, thus giving relatively lower conversion for the diamination (44%).

Table 6.

CuBr-catalyzed diamination of (E)-nona-1,3-diene (4b) with nitrogen sources 1-3a

The diamination was carried out with diene 4b (0.20 mmol), nitrogen source (1, 2, or 3) (0.30 mmol), and CuBr (0.020 mmol) in CDCl3 (0.4 mL) in a 1.5 mL vial at room temperature under Ar atmosphere for 20 h.

The conversion was based on diene 4b and determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

The ratio of [5] to [8] was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

Scheme 8.

Conclusion

Mechanistic studies have shown that the Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination of conjugated dienes proceeds via two distinct mechanistic pathways (Scheme 4). The reaction begins with the cleavage of the N-N bond of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) by the Cu(I) catalyst to form four-membered Cu(III) species A and Cu(II) radical species B, which are in rapid equilibrium. For the internal diamination, Cu(III) species A coordinates with conjugated diene 4 to form olefin-Cu complex D, which undergoes migratory insertion and subsequent reductive elimination to form internal diamination product 5 and regenerate the Cu(I) catalyst. For the terminal diamination, nitrogen radical B adds to the terminal double bond of conjugated diene 4 to form Cu(II) allyl radical species C which undergoes the subsequent C-N bond formation to give terminal diamination product 8 and regenerate the Cu(I) catalyst. The existence of nitrogen radical intermediate B was supported by EPR spectroscopy.

Kinetic studies have shown that the diamination is first-order in N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1), zero-order in olefin, and first-order in total Cu(I) catalyst, suggesting that the cleavage of the N-N bond of 1 by the Cu(I) catalyst is the rate-determining step. Studies with para-substituted 1-phenyl-1,3-butadienes have shown that the Cu(I)-catalyzed terminal diamination was favored by both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents. A good correlation of the Hammett plot with radical-based substituent constants σ• supports the proposed radical mechanism for the terminal diamination. The CuBr-catalyzed diamination of para-substituted 1-phenyl-1,3-butadienes afforded a mixture of terminal and internal diamination products (5 and 8). The regioselectivity ([5]/[8]) had a good Hammett correlation with 0.23σ• + 0.77σp (Figure 10), suggesting the substituent constant σp contributes more to regioselectivity than the radical-based substituent constant σ• does. The negative slope indicates that the internal diamination with Cu(III) intermediate A is electrophilic. Conjugated dienes with good radical-stabilizing groups such as 1-aryl-1,3-butadienes are effective substrates for terminal diamination. Electron-rich dienes favor the internal diamination. Besides diene substrates, the competition between the terminal and internal diamination is also dependent upon reaction conditions such as Cu(I) catalyst and ligand,29 as well as the nitrogen source. N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1) is the most regioselective nitrogen source for the CuBr-catalyzed internal diamination of conjugated dienes, and N,N-di-t-butyl-3-(cyanimino)-diaziridine (3) exhibits the highest regioselectivity for terminal diamination.

The current mechanistic studies have shown that Cu(III) and Cu(II) species can coexist in rapid equilibrium in the catalytic cycle of the diamination. The Cu(III) species accounts for a concerted reaction pathway leading to internal diamination, whereas the Cu(II) species accounts for a radical reaction pathway leading to terminal diamination. The extent of the involvement of the Cu(III) or Cu(II) species depends upon reaction conditions and substrates used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the generous financial support from the General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (GM083944-04).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: The procedures for diamination, kinetic studies, EPR study, studies of substituent effect and nitrogen sources, and characterization data along with NMR spectra (42 pages).

References

- 1.For leading reviews, see: Lucet D, Gall TL, Mioskowski C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2580. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981016)37:19<2580::AID-ANIE2580>3.0.CO;2-L.. Mortensen MS, O’Doherty GA. Chemtracts: Org Chem. 2005;18:555.. Kotti SRSS, Timmons C, Li G. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;67:101. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00347.x.. Kizirian J-C. Chem Rev. 2008;108:140. doi: 10.1021/cr040107v.. Lin G-Q, Xu M-H, Zhong Y-W, Sun X-W. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:831. doi: 10.1021/ar7002623.. Jensen KH, Sigman MS. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:4083. doi: 10.1039/b813246a.. de Figueiredo RM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:1190. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804362.. Cardona F, Goti A. Nat Chem. 2009;1:269. doi: 10.1038/nchem.256.. Chemler SR. J Organomet Chem. 2011;696:150. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.08.041.

- 2.For leading references on metal-free diamination, see: Lavilla R, Kumar R, Coll O, Masdeu C, Bosch J. Chem Commun. 1998:2715.. Lavilla R, Kumar R, Coll O, Masdeu C, Spada A, Bosch J, Espinosa E, Molins E. Chem Eur J. 2000;6:1763. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(20000515)6:10<1763::aid-chem1763>3.0.co;2-r.. Li G, Kim SH, Wei H-X. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:8699.. Booker-Milburn KI, Guly DJ, Cox B, Procopiou PA. Org Lett. 2003;5:3313. doi: 10.1021/ol035374m.. Chen D, Timmons C, Wei H-X, Li G. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5742. doi: 10.1021/jo030098a.. Pei W, Wei H-X, Chen D, Headley AD, Li G. J Org Chem. 2003;68:8404. doi: 10.1021/jo030193j.. Timmons C, Chen D, Xu X, Li G. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:3850.. Timmons C, Chen D, Barney CE, Kirtane S, Li G. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:12095.. Wu H, Ji X, Sun H, An G, Han J, Li G, Pan Y. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4555.. Li H, Widenhoefer RA. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4827. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.03.082.

- 3.For examples of metal-mediated diamination, see: Tl: Gómez Aranda V, Barluenga J, Aznar F. Synthesis. 1974:504.. Os: Chong AO, Oshima K, Sharpless KB. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:3420.. Muñiz K. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:2243.. Pd: Bäckvall J-E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978:163.. Hg: Barluenga J, Alonso-Cires L, Asensio G. Synthesis. 1979:962.. Co: Becker PN, White MA, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:5676.. Mn: Fristad WE, Brandvold TA, Peterson JR, Thompson SR. J Org Chem. 1985;50:3647.

- 4.For recent Cu(II)-promoted diamination, see: Zabawa TP, Kasi D, Chemler SR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11250. doi: 10.1021/ja053335v.. Zabawa TP, Chemler SR. Org Lett. 2007;9:2035. doi: 10.1021/ol0706713.. Sequeira FC, Turnpenny BW, Chemler SR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:6365. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003499.

- 5.For metal-catalyzed diamination with TsNCl2 or TsNBr2, see: Li G, Wei H-X, Kim SH, Carducci MD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4277. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4277::AID-ANIE4277>3.0.CO;2-I.. Wei H-X, Kim SH, Li G. J Org Chem. 2002;67:4777. doi: 10.1021/jo0200769.. Timmons C, Mcpherson LM, Chen D, Wei H-X, Li G. J Peptide Res. 2005;66:249. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2005.00294.x.. Han J, Li T, Pan Y, Kattuboina A, Li G. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;71:71. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00604.x.

- 6.For Pd(II)-catalyzed diamination, see: Bar GLJ, Lloyd-Jones GC, Booker-Milburn KI. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7308. doi: 10.1021/ja051181d.. Streuff J, Hövelmann CH, Nieger M, Muñiz K. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14586. doi: 10.1021/ja055190y.. Muñiz K. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14542. doi: 10.1021/ja075655f.. Muñiz K, Hövelmann CH, Streuff J. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:763. doi: 10.1021/ja075041a.. Hövelmann CH, Streuff J, Brelot L, Muñiz K. Chem Commun. 2008:2334. doi: 10.1039/b719479j.. Muñiz K, Hövelmann CH, Campos-Gómez E, Barluenga J, González JM, Streuff J, Nieger M. Chem Asian J. 2008;3:776. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700373.. Muñiz K, Streuff J, Chávez P, Hövelmann CH. Chem Asian J. 2008;3:1248. doi: 10.1002/asia.200800148.. Sibbald PA, Michael FE. Org Lett. 2009;11:1147. doi: 10.1021/ol9000087.. Sibbald PA, Rosewall CF, Swartz RD, Michael FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15945. doi: 10.1021/ja906915w.. Iglesias A, Pérez EG, Muñiz K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8109. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003653.. Muñiz K, Kirsch J, Chávez P. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:689.

- 7.For Ni(II) and Au(I)-catalyzed diamination, see: Muñiz K, Streuff J, Hövelmann CH, Núñez A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:7125. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702160.. Muñiz K, Hövelmann CH, Streuff J, Campos-Gómez E. Pure Appl Chem. 2008;80:1089.. Iglesias A, Muñiz K. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:10563. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901199.

- 8.For a recent Au(I)-catalyzed intramolecular diamination of allenes via dihydroamination, see: Li H, Widenhoefer RA. Org Lett. 2009;11:2671. doi: 10.1021/ol900730w.

- 9.For Pd(0)-catalyzed diamination of conjugated dienes using 1, see: Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:762. doi: 10.1021/ja0680562.. Du H, Yuan W, Zhao B, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11688. doi: 10.1021/ja074698t.. Xu L, Du H, Shi Y. J Org Chem. 2007;72:7038. doi: 10.1021/jo0709394.. Xu L, Shi Y. J Org Chem. 2008;73:749. doi: 10.1021/jo702167u.. Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. Org Synth. 2009;86:315.. Zhao B, Du H, Cui S, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3523. doi: 10.1021/ja909459h.

- 10.For Pd(0)-catalyzed allylic and homoallylic C-H diamination of terminal olefins using 1, see: Du H, Yuan W, Zhao B, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7496. doi: 10.1021/ja072080d.. Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8590. doi: 10.1021/ja8027394.. Fu R, Zhao B, Shi Y. J Org Chem. 2009;74:7577. doi: 10.1021/jo9015584.. Zhao B, Du H, Fu R, Shi Y. Org Synth. 2010;87:263.

- 11.For Pd(0)-catalyzed dehydrogenative diamination of terminal olefins using 2, see: Wang B, Du H, Shi Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8224. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803184.

- 12.For Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination of conjugated dienes using 1, see: Yuan W, Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. Org Lett. 2007;9:2589. doi: 10.1021/ol071105a.. Du H, Zhao B, Yuan W, Shi Y. Org Lett. 2008;10:4231. doi: 10.1021/ol801605w.. Zhao B, Du H, Shi Y. J Org Chem. 2009;74:8392. doi: 10.1021/jo901685c.

- 13.For Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination of 1,1-disubstituted terminal olefins using 1, see: Wen Y, Zhao B, Shi Y. Org Lett. 2009;11:2365. doi: 10.1021/ol900808z.

- 14.For Cu(I)-catalyzed diamination of terminal olefins using 2, see: Zhao B, Yuan W, Du H, Shi Y. Org Lett. 2007;9:4943. doi: 10.1021/ol702061s.

- 15.For Cu(I)-catalyzed cycloguanidination of olefins using 3, see: Zhao B, Du H, Shi Y. Org Lett. 2008;10:1087. doi: 10.1021/ol702974s.

- 16.For a leading review on diaziridinones, see: Heine HW. In: The Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds. Hassner A, editor. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 1983. p. 547.

- 17.For the preparation of N,N-di-t-butyldiaziridinone (1), see: Greene FD, Stowell JC, Bergmark WR. J Org Chem. 1969;34:2254.. ref. 9e..

- 18.For the preparation of N,N-di-t-butylthiadiaziridine 1,1-dioxide (2), see: Timberlake JW, Alender J, Garner AW, Hodges ML, Özmeral C, Szilagyi S, Jacobus JO. J Org Chem. 1981;46:2082.. Ramirez TA, Zhao B, Shi Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:1822. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.01.114.

- 19.For the preparation of N,N-di-t-butyl-3-(cyanimino)-diaziridine (3), see: Quast H, Schmitt E. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1969;8:448.. L’abbé G, Verbruggen A, Minami T, Toppet S. J Org Chem. 1981;46:4478.. Mestres R, Palomo C. Synthesis. 1980:755.

- 20.The insertion of Ni and Pd to the N-N bond of diaziridinone has been reported, see: Komatsu M, Tamabuchi S, Minakata S, Ohshiro Y. Heterocycles. 1999;50:67.

- 21.For examples of cis-aminopalladation, see: Isomura K, Okada N, Saruwatari M, Yamasaki H, Taniguchi H. Chem Lett. 1985:385.. Ney JE, Wolfe JP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3605. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460060.. Brice JL, Harang JE, Timokhin VI, Anastasi NR, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2868. doi: 10.1021/ja0433020.. Liu G, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7179. doi: 10.1021/ja061706h.. Fritz JA, Nakhla JS, Wolfe JP. Org Lett. 2006;8:2531. doi: 10.1021/ol060707b.

- 22.For a recent leading review on π-allyl Pd chemistry, see: Trost BM. J Org Chem. 2004;69:5813. doi: 10.1021/jo0491004.

- 23.For a recent book on Pd, see: Tsuji J. Palladium Reagents and Catalysts: New Perspective for the 21st Century. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2004.

- 24.For a leading review on metal promoted radical reactions, see: Iqbal J, Bhatia B, Nayyar NK. Chem Rev. 1994;94:519.

- 25.For leading reviews on CuX-catalyzed atom transfer reactions see: Patten TE, Matyjaszewski K. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:895.. Clark AJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2002;31:1. doi: 10.1039/b107811a.

- 26.For leading references on nitrogen-centered radicals, see: Stella L. In: Radicals in Organic Synthesis. Renaud P, Sibi MP, editors. Vol. 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2001. p. 407.. Guin J, Mück-Lichtenfeld C, Grimme S, Studer A. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4498. doi: 10.1021/ja0692581.

- 27.For leading references on Cu(I)-catalyzed homolytic cleavage of N-O bonds of oxaziridines, see: Aubé J, Peng X, Wang Y, Takusagawa F. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5466.. Aubé J. Chem Soc Rev. 1997;26:269.. Black DStC, Edwards GL, Laaman SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:5853.. Black DStC, Edwards GL, Laaman SM. Synthesis. 2006:1981.

- 28.For a leading review on organocopper reagents, see: Lipshutz BH, Sengupta S. Org React. 1992;41:135.

- 29.(a) Zhao B, Peng X, Cui S, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11009. doi: 10.1021/ja103838d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cornwall RG, Zhao B, Shi Y. Org Lett. 2011;13:434. doi: 10.1021/ol102767j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.For leading references on Cu(II) species and reactions involving Cu(II) intermediates, see: Noack M, Göttlich R. Chem Commun. 2002:536. doi: 10.1039/b111656h.. Pintauer T, Eckenhoff WT, Ricardo C, Balili MNC, Biernesser AB, Noonan SJ, Taylor MJW. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:38. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802048.. Ricardo C, Pintauer T. Chem Commun. 2009:3029. doi: 10.1039/b905839g.. Xiao Z, Matsuo Y, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12234. doi: 10.1021/ja1056399.

- 31.For leading references on Cu(III) species and reactions involving Cu(III) intermediates, see: Margerum DW, Chellappa KL, Bossu FP, Burce GL. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:6894. doi: 10.1021/ja00856a065.. Keyes WE, Dunn JBR, Loehr TM. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:4527.. Anson FC, Collins TJ, Richmond TG, Santarsiero BD, Toth JE, Treco BGRT. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2974.. Ribas X, Jackson DA, Donnadieu B, Mahía J, Parella T, Xifra R, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Llobet A, Stack TDP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2991. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020816)41:16<2991::AID-ANIE2991>3.0.CO;2-6.. Aboelella NW, Kryatov SV, Gherman BF, Brennessel WW, Young VG, Jr, Sarangi R, Rybak-Akimova EV, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16896. doi: 10.1021/ja045678j.. Xifra R, Ribas X, Llobet A, Poater A, Duran M, Solà M, Stack TDP, Benet-Buchholz J, Donnadieu B, Mahía J, Parella T. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:5146. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500088.. Bertz SH, Cope S, Murphy M, Ogle CA, Taylor BJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7208. doi: 10.1021/ja067533d.. Gärtner T, Henze W, Gschwind RM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11362. doi: 10.1021/ja074788y.. Falciola CA, Alexakis A. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:3765.. Phipps RJ, Grimster NP, Gaunt MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8172. doi: 10.1021/ja801767s.. Huffman LM, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9196. doi: 10.1021/ja802123p.. King AE, Brunold TC, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5044. doi: 10.1021/ja9006657.. Yao B, Wang D, Huang Z, Wang M. Chem Commun. 2009:2899. doi: 10.1039/b902946j.. Yang L, Lu Z, Stahl SS. Chem Commun. 2009:6460. doi: 10.1039/b915487f.. He C, Guo S, Huang L, Lei A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8273. doi: 10.1021/ja1033777.

- 32.For leading references on π-allyl copper(III) species and reactions involving π-allyl copper(III) intermediates, see: Yamanaka M, Kato S, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6287. doi: 10.1021/ja049211k.. Nakanishi W, Yamanaka M, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1446. doi: 10.1021/ja045659+.. Yoshikai N, Zhang S-L, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12862. doi: 10.1021/ja804682r.. Bartholomew ER, Bertz SH, Cope S, Murphy M, Ogle CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11244. doi: 10.1021/ja801186c.

- 33.For leading reviews on mechanistic studies on transition-metal catalysis, see: Masel RI. Chemical Kinetics and Catalysis. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2001. . Bhaduri S, Mukesh D. Homogeneous Catalysis: Mechanisms and Industrial Applications. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2000. . Heaton B. Mechanisms in Homogeneous Catalysis: a Spectroscopic Approach. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. . Blackmond DG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4302. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462544.

- 34.For leading references on mechanistic studies on copper-catalyzed reactions, see: Krauss SR, Smith SG. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:141.. Lockhart TP. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:1940.. Lim PK, Zhong Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:8404.. Evans DA, Faul MM, Bilodeau MT. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:2742.. Li Z, Quan RW, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5889.. Evans DA, Burgey CS, Kozlowski MC, Tregay SW. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:686.. Díaz-Requejo MM, Belderrain TR, Nicasio MC, Prieto F, Pérez PJ. Organometallics. 1999;18:2601.. Brandt P, Södergren MJ, Andersson PG, Norrby P-O. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:8013.. Lammertsma K, Ehlers AW, McKee ML. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14750. doi: 10.1021/ja0349958.. Strieter ER, Blackmond DG, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4120. doi: 10.1021/ja050120c.. Rodionov VO, Fokin VV, Finn MG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:2210. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461496.. Rodionov VO, Presolski SI, Díaz DD, Fokin VV, Finn MG. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12705. doi: 10.1021/ja072679d.. Srivastava RS, Tarver NR, Nicholas KM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15250. doi: 10.1021/ja0751072.. Michaelis DJ, Ischay MA, Yoon TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6610. doi: 10.1021/ja800495r.. Strieter ER, Bhayana B, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:78. doi: 10.1021/ja0781893.. King AE, Brunold TC, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5044. doi: 10.1021/ja9006657.. Kaddouri H, Vicente V, Ouali A, Ouazzani F, Taillefer M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:333. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800688.. Özen C, Konuklar AS, Tūzūn NS. Organometallics. 2009;28:4964.. Balili MNC, Pintauer T. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:5642. doi: 10.1021/ic100540q.

- 35.For additional examples of terminal diamination of 1-aryl-1,3-butadienes with CuCl-P(OPh)3 and 1, see: ref 12a.

- 36.For leading references on radical-based substituent constant σ•, see: Fischer TH, Meierhoefer AW. J Org Chem. 1978;43:224.. Dinctürk S, Jackson RA. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans II. 1981:1127.. Jiang X-K, Ji G-Z. J Org Chem. 1992;57:6051.

- 37.For leading references on substituent effect studies, see: Lehmann J, Lloyd-Jones GC. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:8863.. Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ, Brookhart M, Templeton JL. Organometallics. 1997;16:4399.

- 38.For leading references on Hammett substituent constant σp, see: Jaffé HH. Chem Rev. 1953;53:191.. Brown HC, Okamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:4979.. Mcdaniel DH, Brown HC. J Org Chem. 1958;23:420.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.