Abstract

Total atherosclerotic occlusion is a leading cause of death. Recent animal models of this disease are devoid of cell-mediated calcification and arteries are often not occluded gradually. This study is part of a project with the objective of developing a new model featuring the above two characteristics using a tissue engineering scaffold. The amount and distribution of calcium deposits in primary human osteoblast (HOB) cultures on polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds under flow conditions were investigated. HOBs were cultured on PCL scaffolds with TGF-β1 loadings of 0 (control), 5, and 50 ng. HOB/PCL constructs were cultured in spinner flasks. Under flow conditions, cell numbers present in HOB cultures on PCL scaffolds increased from day-7 to day-14, and most calcification was induced at day-21. TGF-β1 loadings of 5 ng and 50 ng did not show a significant difference in ALP activity, cell numbers, and amount of calcium deposited in HOB cultures. But calcium staining showed that 50 ng of TGF-β1 had higher calcium deposited both on days 21, and 28 under flow conditions compared with 5 ng of loading. Amount of calcium deposited by HOBs on day-28 showed a decrease from their levels on day-21. PCL degradation may be a factor contributing to this loss. The results indicate that cell-induced calcification can be achieved on PCL scaffolds under flow conditions. In conclusion, TGFβ1-HOB loaded PCL can be applied to create a model for total atherosclerotic occlusion with cell-deposited calcium in animal arteries.

1. INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis is the number one cause of mortality and morbidity in North America (Trion and van der Laarse 2004; Yanni 2004). This disease begins in the form of a fatty streak, and then progresses to fibro-lipid plaques in the lumen area of arteries (Daugherty 2002; Narayanaswamy et al. 2000). Calcium deposits are often seen in the lipid core of plaques (Alexopoulos and Raggi 2009) and calcification is considered a surrogate marker for advanced atherosclerosis (Hsu et al. 2008). Intracellular traffic is a highly regulated process (Cabrera et al. 2010; Sha et al. 2007; Sha et al. 2009). Similarly, calcification in vessel walls is an actively regulated, cell-mediated process resembling bone formation (Sinha et al. 2009). Numerous cell types within the vessel wall undergo phenotypic changes displaying many characteristics of osteoblasts (Giachelli 2005; Sinha et al. 2009). These cells include pericytes, myofibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, and calcifying vascular cells (Sinha et al. 2009; Vattikuti and Towler 2004). It has been previously recorded that cells produce calcified matrix and promote nucleation of calcium deposits in the vessel wall (Abedin et al. 2004; Giachelli 2004). As calcified plaque grows thicker, the artery lumen narrows. With the additional participation of inflammation and other cellular events, the blood vessel eventually can be totally occluded with significant cell-mediated calcification.

There is a strong need to model total atherosclerotic occlusion with cell-deposited calcium in animal arteries. Such a model will facilitate the development of new therapies for the most severe atherosclerosis. However, most animal models occlude arteries instantly using ameroid constrictors or thrombin (Radke et al. 2006; Segev et al. 2005), which do not mimic the gradual occlusion in chronic diseases. Some recent new models achieved calcified total occlusion using a gelatin sponge mixed with bone powder or a polymer coated with calcium and phosphate ions (Suzuki et al. 2008; Suzuki et al. 2009). Calcification was detected in arteries, but the question remains if this calcium was induced by cells, as is the case in total occlusion in humans. Our group has previously developed the interventional cardiology techniques to implant polymeric scaffolds into coronary arteries of pigs (Prosser et al. 2006). Although the results were promising and showed that arteries achieved gradual total occlusion due to the presence of scaffolds, no calcium deposits were detected.

The overall aim of this project is to establish total atherosclerotic occlusion with cell-mediated calcification in an animal artery using tissue-engineered scaffolds. In this study, as one of the first steps toward this goal, primary human osteoblasts (HOBs) were grown on polymeric scaffolds under flow conditions in a spinner flask bioreactor and their ability to deposit calcium in the extra-cellular matrix and on the scaffold was evaluated. These particular cells were used because most vasculature cells need to be first differentiated into osteoblastic phenotypes prior to their depositing calcium in the vessel wall (Abedin et al. 2004; Shioi et al. 2000). A spinner flask bioreactor was chosen because the convective forces generated in the spinner flask increases the external mass-transfer of oxygen and nutrients in a 3D construct (Martin et al. 2004) and reduces the stagnant cell layer on the surface of scaffolds (Chen and Hu 2006; Freed et al. 2006; Martin et al. 2004). Many applications in bone tissue engineering have used spinner flasks (Wang et al. 2009). Bone cell cultures in spinner flasks had higher number of cells, more differentiation, earlier osteoblastic expression, and more calcification in extracellular matrix in comparison with those in rotating wall vessels (Sikavitsas et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2009).

In our previous investigation, an in vitro cell-calcium construct was successfully generated using primary human osteoblasts (HOBs) on polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds with TGF-β1 loading under static culture conditions (Zhu et al. 2011). A wide range of TGF-β loading on scaffolds, 0 (control), 5, 10, 50, and 100 ng, was tested with in the media containing 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The lower amount of TGF-β1 loading (5 ng) showed most calcification, high DNA synthesis, and high ALP activity in HOB cultures under static conditions. The purpose of this present study was to investigate whether calcification can be maintained under flow conditions since the cell-scaffold construct will be expected to experience blood flow in animal arteries. TGF-β1 loading of 5 ng was picked as the optimized dose from our previous study. Another higher dose of TGF-β1 at 50 ng was also tested in the consideration that dynamic flow may wash away parts of growth factors coated on PCL scaffolds.

2. METHODS

2.1 Preparation of PCL scaffolds

PCL scaffolds were prepared by the vibration particle/salt leaching technique as previously reported (Chim et al. 2003). Briefly, 1.33 g poly ε-caproplactone (PCL, Biringham Polymer Inc. Birmingham, AL) with an inherent viscosity of 1.14 dl/g and an average molecular weight of 128k Da was dissolved in 11.37 ml dichloromethane (purity >=98%; Sigma) under continuous stirring. 7.87 g of NaCl (particle size 250 μm~500 μm) was spread evenly at the bottom of a mold with a rectangular cavity and the polymer solution was added on top. Under continuous air flow two more sets of salt (7.87 g, and 3.50 g) were sequentially added into the mold. The whole process was performed while vibrating the mold continuously using a vortex meter to evenly distribute the NaCl particles. After 24 hours of solvent evaporation, the salt-polymer composite was placed in a vacuum (5000 m Torr) at 45 °C for 24 hours, and scaffolds were extracted using a metal circulator punch. Thus prepared scaffolds were then immersed in ddH2O for 48 hours, dried in a lyophilizer for another 24 hours, and stored under vacuum until usage. The PCL scaffolds were cylindrical, with a diameter of 5 mm and a length of 5 mm. They had a porosity of approximately 91% and a permeability of 24.4 ± 11.3 × 10−8 m4/NS (Chim et al. 2003). Before cell culture, the PCL scaffolds were soaked in 75% ethanol for 15 minutes and then rinsed with PBS three times.

2.2 TGF-β1 Coating on PCL Scaffolds

PCL scaffolds were first soaked in 20 μg/ml fibronectin solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) overnight. BSA solution at 1% was prepared by dissolving 0.1 g bovine serum albumin fraction V (Sigma-Aldrich) in 10 ml of sterilized PBS. A stock concentration of TGF-β1 (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at 40 ng/μl (in 4 mM HCl) was diluted to aliquots using 1% BSA to achieve final quantities of TGF-β1 at 5 ng, and 50 ng per 20 μl of volume respectively. Then, each 20 μl of aliquot was dropped onto corresponding fibronectin coated PCL scaffolds using a pipette. Scaffolds with no TGF-β1 loading were used as controls. Fibronectin was used as a medium for binding both the test cells and TGF-β1 to PCL scaffolds.

2.3 Primary Human Osteoblast Culture

Primary human osteoblasts, osteoblast basal media, SingleQuotes®, and Trypsin/EDTA were purchased from Lonza Walkersville, Inc. Walkersville, MD. Primary human osteoblasts (HOBs) were cultured in osteoblast basal media supplemented with SingleQuotes in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells were maintained in T-150 flasks, and the culture media was changed once every two days. When HOBs reached 80–90% confluence, they were trypsinized using Trypsin/EDTA, and 7.5 × 105 cells were used to establish the next culture in another T-150 flask. Cells from the third passage were used for the experiments. HOBs were counted using a hemocytometer, and 2 × 105 cells were seeded onto each PCL scaffold using a drop technique. Media used for experiments was osteogenic media supplemented with 10−10 M dexamethasone (Dex). The osteogenic media was α-MEM, (α-minimum essential medium, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 7% FBS, 1% antibiotic/antimycotic stabilized (10,000 units/ml penicillin G, 10 mg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 25 μg/ml amphotericin B), (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 100 μg/ml L-ascorbic acid, and 5 mM β-glycerophosphate (β-GP).

HOB/PCL constructs prepared for dynamic flow experiments were first cultured in 24 well plates for 5 days under static conditions. This step was to facilitate initial cell adhesion and growth on scaffolds. At day 6, HOB/PCL scaffolds were removed from static culture under sterile conditions, and placed in 125 ml glass spinner flasks (Corning Cat# 4500-125, Lowell MA). The spinning speed was initially set at 5 rpm, and then increased to 20 rpm on day 7 and maintained constant thereafter.

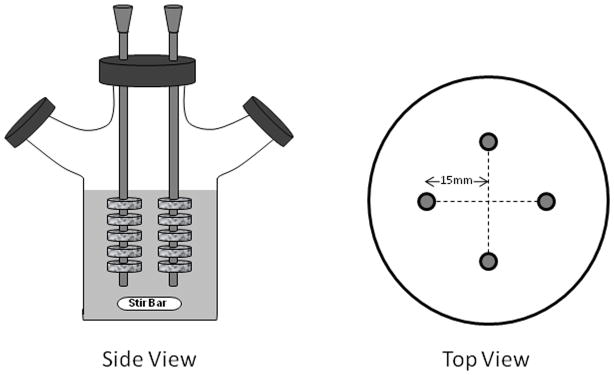

2.4 Bioreactor Set-up

To install HOB/PCL cultures in the bioreactor, four holes were drilled through the cap of the spinner flask. These holes were evenly apart from each other in a circle, with each one having a distance of 15 mm from the center of the cap. Four stainless steel needles (0.5 mm in diameter) were hung symmetrically inside the spinner flask through the 4 holes on the cap (Figure 1). Five HOB/PCL constructs were threaded on each needle and each scaffold was placed 10 mm apart from adjacent ones using silicon tubing spacers (inner diameter = 0.5 mm, Cole Parmer, Chicago, IL). The lowest construct on each needle was 20 mm from the bottom of the flask. A 51 mm magnetic stirrer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) was placed at the bottom of the flask and rotated freely. A volume of 250 ml of media was added to the flask to completely submerge all 20 scaffolds. Media were changed after every 3 – 4 days. At pre-determined time points of 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, five constructs at the bottom of the flask were harvested for further biological assays. The rest of the specimens were moved downward by 10 mm on the needles, and they were cultured in the spinner flask continuously until the time for harvest.

Figure 1.

Schematic views of spinner flask bioreactors from side and the top

2.5 Alkaline Phosphatase Activity Measurement

The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was assessed using Senso Lyte FDP secreted alkaline phosphatase reporter gene assay (AnaSpec, San Jose, CA). At the end of the prescribed time points, HOB/PCL constructs were rinsed with PBS three times and lysed using 200 μl of 0.02% Triton X-100. Twenty μl of cell lysate was incubated with the fluorogenic substrates in the kit for 25 minutes in dark. Fluorescence was measured with a fluorescent microplate reader FLX800 (Bio-Tek Instrument) using an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm. Commercial ALP enzyme (Sigma) at 1:500 and 1:1000 dilution ratios were used as controls.

2.6 Quantification of Cell Numbers

The HOB/PCL constructs were washed with PBS three times and lysed in 200 μl of 0.02% Triton X-100. The specimens were then shaken in an orbital shaker at 0 °C for 30 minutes. After centrifugation at 40,000 rpm for 10 minutes, the supernatant of each sample containing clear cell lysates was collected. DNA content from lysates was quantified using the PicoGreen DNA quantification assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The fluorescence of samples was read by a fluorescent microplate reader FLX800 (Bio-Tek Instrument, Winooski, VT) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm, and an emission wavelength of 528 nm. Calf Thymus DNA (Invitrogen) of known concentration was measured in parallel with samples in order to generate a DNA standard curve. DNA quantities of each sample were derived from its respective fluorescence reading based on this standard curve. Using the same PicoGreen DNA quantification assay, another standard curve of a set of known cell numbers and their absorbance was generated. Thus, the cell numbers of each specimen was derived from the above two standard curves.

2.7 Quantification of Calcium Content

Calcium content was measured using a method based on the interaction of calcium with o-Cresolphthalein. Cell-polymer constructs were washed with PBS three times followed by immersion in 150 μl of 0.6 N HCl overnight at 4 °C to release calcium deposits from culture matrix. Fifty μl of sample solution was reacted with colorgenic reagents of a calcium reagent set (Pointe Scientific, Inc. Canton, MI) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance of reacted solution was then measured using a spectrophotometer at 560 nm within 20 minutes. To prepare a negative control for this assay, HOBs (2 × 105 cells) were seeded on PCL scaffolds with no TGF-β1 coating, and were cultured in growth media (α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS). Dex was not added to the growth media. Negative controls were supposed to have only minor calcium deposits, and their levels were lower than any of the three study groups. These controls were included at every study end-point. The absorbance of negative controls was set as the baseline, and was subtracted from readings obtained from the actual samples at each time point. The actual negative control data is not presented here.

2.8 Fluorescent Calcification and DAPI Staining

Calcification of HOB cultures on PCL scaffolds was stained by a fluorogenic calcification assay, and images were viewed under a confocal laser scanning microscope. Briefly, the specimens were rinsed with PBS three times, and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at 4 °C overnight. They were then embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA), longitudinally sectioned by a Leica cryostat and mounted on silane coated microscope glass slides. Reagents from an OsteoImage mineralization assay kit (Lonza, Walksville, MD) were used to stain calcium deposits according to manufacturer’s instructions. After staining, slides were mounted in mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and were observed under an Olympus FV-1000 Laser Scanning microscopy system with Olympus IX-81 microscope at a magnification of 10×. Spatial distribution of calcium deposits was assessed by a three line argon laser (λex=488 nm, λem=520 nm), and DAPI-stained HOB nuclei were revealed by scanning with a diode laser (λex=405 nm, λem=460 nm). Calcium deposits were stained green, while cell nuclei were stained blue. Three specimens were used for each group of TGF-β1 loading on PCL scaffolds, and the images were taken on three different slides from each scaffold.

2.9 Quantification of Calcification Area

Area of calcium deposits was measured based on fluorescent calcium images using Image J software (version 1.4 National Institute of Health). Three samples were taken from each study group at each time point, and three images were used from one specimen to measure the amount of calcium. The field of view of each image was 0.41 mm2.

2.10 Polymer Weight Loss

Each PCL scaffold was immersed in 10 ml of PBS in a sealed 15 mL centrifuge tube. These specimens were placed in a 37 °C incubator for 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 days with biweekly PBS changes. At the end of each test time point, scaffolds were removed from the incubator, washed with ddH2O, and vacuum dried for 72 hours. The mass of each scaffold was measured using an electronic micro-balance, and the percent mass remaining was determined.

2.11 Statistical Analysis

For quantitative measurements of cell number, ALP and calcification levels, four samples were used for each group at each time point (7, 14, 21, and 28 days). The degradation study used six samples at days-7, 14, 21, 28, and four samples at day-35. The experimental data collected are presented as “mean ± standard deviation”. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed between various groups. If statistical difference was determined by one way ANOVA, Student Newman Keuls test was then performed to determine the statistical significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) between two individual groups.

3. RESULTS

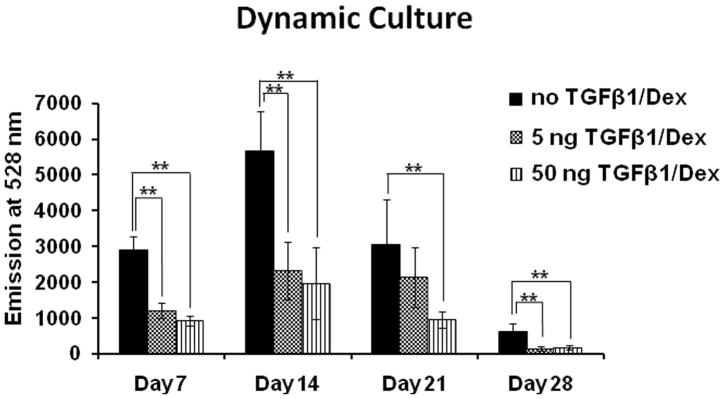

3.1 Intracellular Alkaline Phosphatase Activity on PCL Scaffolds

Alkaline phosphatase activity is a phenotypic indicator of osteoblast maturation and is often used to measure the biological activity of growth factors loaded on biodegradable polymers. Figure 2 illustrates the ALP activity of HOB cultures on PCL scaffolds loaded with 0 ng, 5 ng, and 50 ng of TGF-β1 after 7, 14, 21, and 28 days in dynamic conditions. HOBs on PCL with 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading had lower ALP activity than those on control PCL at all time points from day-7 to day-28 (p<0.01). Intracellular ALP activity on PCL with 5 ng of TGF-β1 was lower than those of control PCL at days 7, 14, and 28 (p<0.01). There was no difference in ALP activity between TGF-β1 doses of 5 ng and 50 ng at any time point. For all three groups, there was a significant increase of ALP activity from day-7 to day-14 (p<0.01 for control group, and p<0.05 for groups with 5 and 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading). On day-14, the ALP activity of for all groups reached their highest levels compared to other days. At day-28, ALP activity of three groups was significantly lower than their respective levels on day-21 (p<0.01). Our data thus suggests that under flow conditions, the highest ALP activity of HOBs occurred on day-14, and the doses of TGF-β1 at 5 ng and 50 ng did not show a significant difference in ALP activity. However, the introduction of TGF-β1 appeared to reduce ALP activity at all time points.

Figure 2.

Intracellular ALP activity of HOBs on PCL scaffolds coated with 0 (control), 5 ng, and 50 ng of TGF-β1 under dynamic conditions (*p<0.05, **p<0.01).

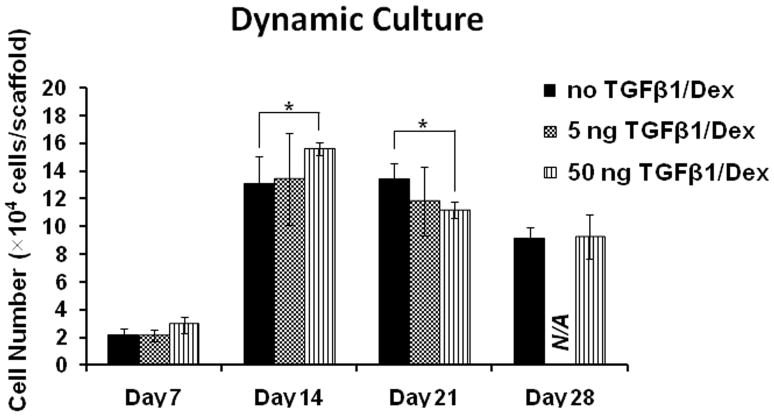

3.2 Cell Number

Figure 3 shows the cell number of HOBs cultured on PCL scaffolds with different loadings of TGF-β1 at 0 ng (control), 5 ng, and 50 ng at days 7, 14, 21, and 28 under dynamic conditions. Unfortunately the data for 5 ng loading at 28 days was lost due to contamination. For all three groups of different TGF-β1 loading, the cell number on day-14 was significantly higher than their respective levels on day-7 (p<0.01). On day-7, cells in dynamic culture had about 12% of the initial cells seeded, however the maximum number of HOBs in dynamic culture reached 1.5 × 105 cells on day-14. On day-14, cells on scaffolds loaded with 50 ng of TGF-β1 had significantly more cells than those on controls (p<0.05). However, on day-21, the same groups had opposite results as the control scaffolds had higher cell numbers than those with 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading (p<0.05). By day-28 the number of HOBs for these two groups did not show a significant difference. Also on day-28, the cell numbers on control scaffolds and those with 50 ng of TGF-β1 were significantly lower than their respective levels on day-21 (p<0.01). Though the amount of cells in both groups decreased from day-21 to day-28, it should be clearly noted that HOBs on control scaffolds had a 4 fold increase from day-7 to day-28, and cells on scaffolds with 50 ng of TGF-β1 had a 3 fold increase from day-7 to day-28. The cell number data demonstrates that after the TGF-β1 coating on PCL, cell seeding efficiency on the scaffold was about 12%. But under flow conditions, the number of cells increased 5.6 times on day-14 from their levels on day-7.

Figure 3.

Cell number of HOBs on PCL scaffolds with none, 5, and 50 ng loading of TGF-β1 in dynamic conditions (*p<0.05, **p<0.01).

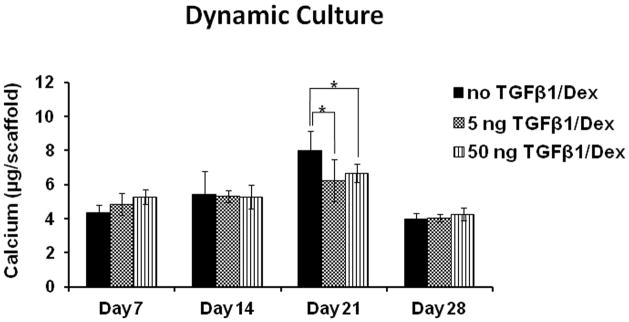

3.3 Quantitative Measurement of Calcium Deposits

Figure 4 shows the amount of calcium deposited in HOB cultures on scaffolds loaded with 0 ng (control), 5 ng, and 50 ng of TGF-β1 after 7, 14, 21, and 28 days under flow conditions. Calcium deposition in HOB cultures gradually increased from day-7 to day-14, and reached the highest level on day-21 for all three groups of scaffolds. On day-28, however, calcification in three study groups decreased significantly from their individual levels on day-21 (p<0.01).

Figure 4.

HOBs were cultured on PCL scaffolds with different doses of TGF-β1 coatings at 0 (control), 5 ng, and 50 ng respectively under flow conditions. The amount of calcium deposited in cultures was measured at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days (*p<0.05, **p<0.01).

On day-21, HOBs on control PCL scaffolds (no TGF-β1 loading) showed a peak for the maximum calcium deposited in all the groups (7.973 ± 1.16 μg; p<0.05), followed by cells on scaffolds with 5 ng of TGF-β1 loading (6.693 ± 0.542 μg). Cultures on scaffolds with 5 ng and 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading did not show significant difference between each other at any time point. HOB cultures on control scaffolds and scaffolds with 50 ng of TGF-β1 coating both had significantly higher amount of calcium deposited on day-21 than their respective levels on day-14 (p<0.05 for the control group; p<0.01 for the group with 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading).

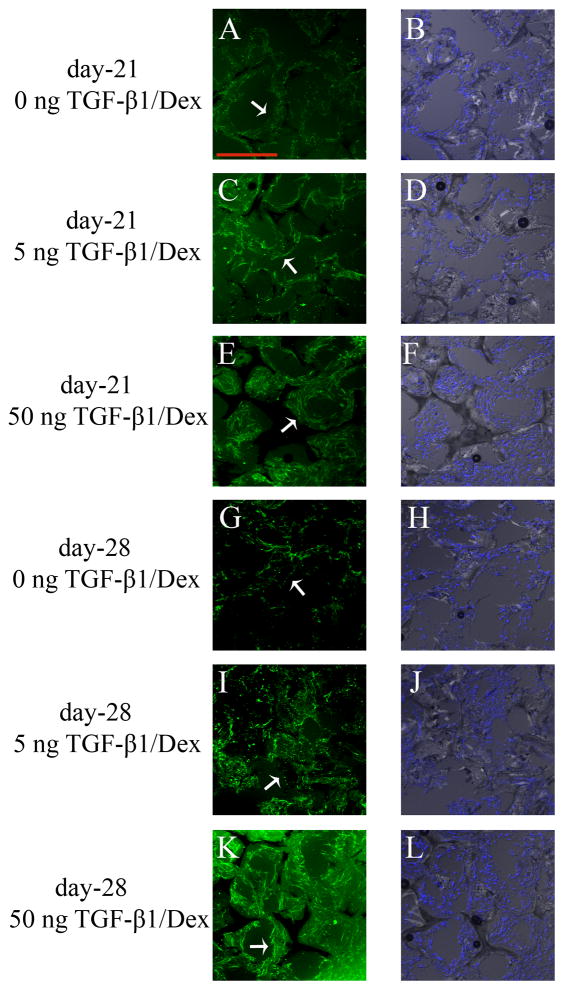

3.4 Imaging of Calcification

Figure 5 shows the typical confocal images of HOBs cultured on PCL scaffolds at day-21 (Figure 23A–F), and day-28 (Figure 23G–L) with TGF-β1 loading of 0, 5, and 50 ng. Calcium deposits were stained green while HOB nuclei were counterstained blue by DAPI. On day-21, maximal calcification was detected in groups with 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading. The results for day-28 were similar to those on day-21, as scaffolds loaded with 50 ng of TGF-β1 had the most extensive calcification in cultures. DAPI staining indicated that HOBs grew extensively in all scaffolds. A comparison of the first and second columns in Fig 5 indicates that calcification and cells co-localize with each other on scaffolds. More calcium deposits were detected where more cells were present on scaffolds (Figure 5E, 5K).

Figure 5.

Calcification staining (green fluorescence) of HOB cultures on PCL scaffolds under dynamic cultures. HOB nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue fluorescence). HOBs were cultured on 0 (A, B), 5 (C, D), and 50 ng (E, F) of TGF-β1 loaded PCL scaffolds, and calcification was imaged at day-21. At day-28, calcium was examined in HOB cultures with 0 (G, H), 5 (I, J), and 50 ng (K, L) of TGF-β1 loading on PCL scaffolds. First column indicates calcium staining. Second column shows the nuclei of HOBs on PCL scaffolds from the same location. Scale bar was 250 μm in A, and this applies from A to R. All arrows point to calcium deposits.

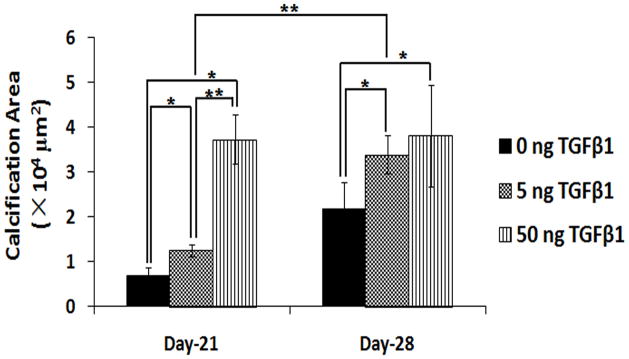

3.5 Quantification of Calcification Area

Figure 6 shows the area of calcium deposits on PCL scaffolds based on fluorescent calcium images. On day-21, scaffolds loaded with 50 ng of TGF-β1 had the highest calcification among the three groups (p<0.05). Groups with 5 ng of TGF-β1 loading had more calcium deposits than the control group (p<0.05). On day-28, both groups of TGF-β1 at 5 ng and 50 ng had more calcification than the control scaffolds which had no TGF-β1 (p<0.05). No difference was observed between these two groups. But calcium deposits on scaffolds with 5 ng of TGF-β1 increased significantly from day-21 to day-28 (p<0.01).

Figure 6.

Quantification of calcification area on PCL scaffolds under dynamic conditions based on fluorescent calcium images. HOBs were cultured on 0 ng (control), 5 ng and 50 ng of TGF- β1 loaded scaffolds for 21 and 28 days (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01).

Figures 5 and 6 suggested that when HOBs were cultured under flow conditions, 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading induced maximum calcium deposits in scaffolds at day-21. Calcification on 5 ng of TGF-β1 increased from day-21 to day-28. Calcium deposits was present extensively both at day-21, and day-28 in dynamic cultures.

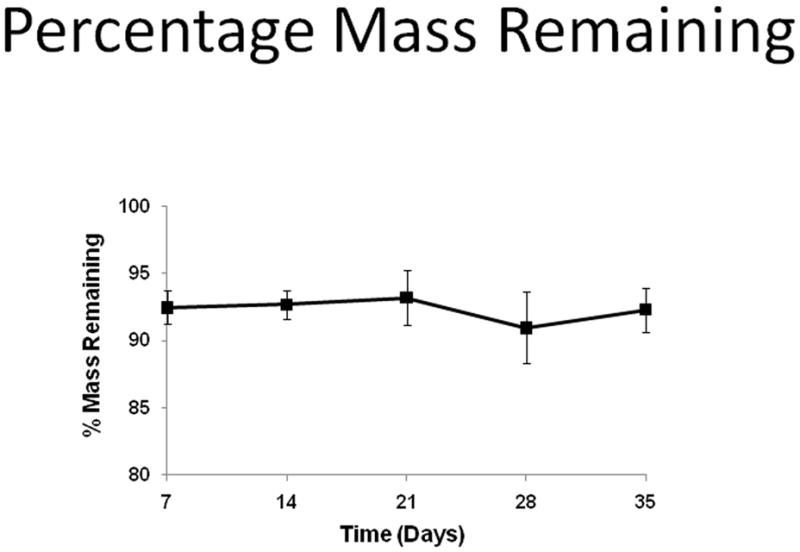

3.6 PCL Weight Loss

Figure 7 shows the percent mass remaining on PCL scaffolds over 35 days under static conditions. No significant difference was detected in the percent mass remaining for up to 35 days. The data indicates that after 35 days in static conditions, the mass of PCL did not decrease significantly.

Figure 7.

Percentage mass remaining of PCL scaffolds over 35 days in PBS immersion under static conditions.

4. DISCUSSION

This study used a spinner flask to investigate the amount and distribution of calcium deposits in primary human osteoblast (HOB) cultures on TGF-β1 loaded polycaprolactone scaffolds under dynamic conditions. Several assays were carried out including ALP activity, cell numbers, amount and distribution of calcification in HOB cultures.

Our data showed that the cell number on scaffolds was relatively low at day-7 compared to day-14. Low initial seeding density might explain this observation. Other research teams have reported that cell seeding efficiency was low on PCL/PLA scaffolds coated with Matrigel (Barralet et al. 2003). More importantly, even with the low seeding efficiency in our study, the cell number of HOBs increased by 6-fold from day-7 to day-14, and reached 1.5 × 105 cells per scaffold in 2 weeks. In addition, DAPI staining showed that cells grew extensively inside the scaffolds by 4 weeks. These cells were able to efficiently undergo differentiation and deposit calcium on scaffolds, as demonstrated in Figures 4 and 5 by quantitative calcification and calcium imaging. Consistent with our results, some studies also reported that HOBs grown on PCL/PLLA scaffolds had relatively low cell number at day-7, but proliferated by more than 3-fold by day-14 and the cell number consistently increased at day-21 (Guarino et al. 2008).

Previous investigations demonstrated that shear force generated by flow is a major factor of how bioreactors influence cell behavior. In a spinner flask, flow is generated by a rotating bar. Its pattern is unsteady, periodic, and turbulent (Bilgen and Barabino 2007; Sucosky et al. 2004). Thus, the resultant spatial distribution of shear force is also non-uniform. Shear force in a spinner flask varies depending upon the position of scaffolds in the glass (i.e. bottom or top, central or far) (Bilgen and Barabino 2007). At a flow rate of 50 rpm, the range of shear force is 0–1.2 dyn/cm2 (Bilgen and Barabino 2007; Sucosky et al. 2004). Studies have shown that human osteoblasts subjected to low shear force of 0.03–0.63 dyn/cm2 have had increased levels of ALP activities, higher cell proliferation, and cell in growth inside scaffolds (Botchwey et al. 2003; Liegibel et al. 2004). When shear force is increased to 14 dyn/cm2 or 20 dyne/cm2, proliferation of human osteoblasts can be either stimulated (Kapur et al. 2003) or inhibited (Schwartz et al. 2007) in comparison with the static culture. In this study, we picked 20 rpm as the speed for our tests. Based on the literature, the mean shear force generated can be expected to be around 0.12–0.44 dyn/cm2. Our results also validated that this shear force falls in the range to favor the growth of human osteoblasts.

Dynamic flow has been proposed to affect cell proliferation, differentiation, and the expression of biomarkers for different types of osteoblasts and their progenitor cells including HOBs (Botchwey et al. 2003; Facer et al. 2005; Fassina et al. 2005; Grellier et al. 2009; Zhao et al. 2007). Previously, in a flow perfusion chamber, human osteoblast-like cells (SAOS-2) cultured on non-degradable polyurethanes scaffolds have had 33% higher cell proliferation, and a 10-fold increase in calcium deposition when compared to the cells cultured under static conditions for 16 days (Fassina et al. 2005). Human osteoblast-like cells had grown predominantly in the interior regions of scaffolds during rotation in high aspect ratio vessels (Botchwey et al. 2003). When grown in rotary cell culture vessel system, human pre-osteoblasts (human embryonic palatal mesenchymal cells) have been observed to start depositing calcium in ECM as early as one week and the amount of calcification was higher than those cultured in 2D tissue plates (Facer et al. 2005).

Overall, these previous studies indicate that under dynamic conditions both cell proliferation and calcification should be enhanced. Since the goal of the present study was to achieve maximum calcification on the cell-PCL constructs, it appears that dynamic conditions should be beneficial. Our results under flow conditions were similar to the above findings as the cell numbers of HOBs were significantly increased at 14, 21, and 28 days in comparison with their respective levels at day-7. From day-7 to day-14, the number of HOBs on PCL scaffolds increased almost 5–6 fold, reaching 1.5 × 105 in dynamic cultures while the number of cells in static conditions did not increase much through 28 days of culture (Zhu et al. 2011).

Groups with TGF-β1 loading of 0, 5, and 50 ng did not show significant difference between each other in cell numbers. One possible reason could be that the flow conditions already stimulated cell growth to nearly maximal level and the effects of flow on cell growth overshadow those of TGF-β1.

The main focus of the data collected on day-28 was to observe quantitative calcification and to image calcium deposits. Separate groups of samples were used for each assay. Although cell number for the group with 5 ng of TGF-β1 at day-28 was unavailable, the data on ALP activity, quantitative calcification, and calcium deposit imaging were carefully measured from well maintained samples. The groups with 0 ng and 50 ng TGF-β1 showed that the cell number at day-28 decreased slightly from day-21, but was still significantly higher than day-7. In lieu of actual cell number data at day-28 for scaffolds with 5 ng of TGF-β1, the trend can be extrapolated from the groups with 0 ng and 50 ng TGF-β1. These predictions are further consistent with our published results of the cell growth curve in static culture with different loadings of 0, 5, and 50 ng TGF-β1 on scaffolds (Zhu et al. 2011).

Our data under flow conditions showed the calcification in HOB cultures reached their maximum levels on day-21. However, one difference we observed between our study and previous investigations is that calcification decreased for all study groups at day-28 in our study. One previous study reported that when rat stem cells were cultured on PCL scaffolds for 21 and 28 days, calcium deposition had not been significantly higher in a high aspect ratio vessel when compared with static conditions (Petrie Aronin et al. 2008).

Our calcium imaging and quantification of calcification based on images (Figures 5 and 6) indicated that 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading had highest calcium deposits at day-21 among all three groups. In addition, the calcification on 5 ng of TGF-β1 increased significantly from day-21 to day-28. This was inconsistent with the quantitative measurement of calcification (Figure 4) where 5 ng and 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading showed similar amounts of calcium deposits. One reason for this could be that the method used for Figure 4 applied HCl to dissolve ECM and collect the calcium. Parts of the calcium deposits could have not dissolved in HCl and still stayed on scaffolds. On the other hand, the method for Figures 5 and 6 used staining to detect calcium directly on matrix. Less calcification would be lost from the latter technique. Thus, Figures 5 and 6 could be closer to the actual calcification conditions on scaffolds.

Our previous data of HOBs on scaffolds loaded with 0, 5, and 50 ng of TGF-β1 under static conditions showed that calcification continuously increased from day-14, through day-21, to day-28 (Zhu et al. 2011). On day-7, the amount of calcium (4 μg per scaffold) deposited under flow conditions was twice the amount of that generated under static cultures. Our results were similar to a previous finding about human pre-osteoblasts (human embryonic platal mesenchymal cells). When grown in rotary cell culture vessel system, these cells were reported to start depositing calcium in ECM as early as one week and the amount of calcium was higher than those cultured in 2D tissue plates (Facer et al. 2005). In our Figure 4 at day 21, calcium deposits by dynamically cultured HOBs had a 1.21 fold increase with 5 ng of TGF-β1 loading, and approximately 4 fold increase with 50 ng of TGF-β1 loading in comparison with static conditions. The data also demonstrates that under flow conditions, calcification in HOB cultures reached their maximum levels earlier than those in static cultures (21 days vs 28 days), and the maximum amount of calcium deposition (7.97 ± 1.16 μg/scaffold) in dynamic culture was the same as that in static culture (8.42 ± 0.64 μg/scaffold) (Zhu et al. 2011). Interestingly, HOBs with 50 ng of TGF-β1 coating on scaffolds were able to deposit significantly higher amount of calcium (6.69 ± 0.54 μg/scaffold) when cultured under dynamic condition compared to static condition (2.20 ± 0.18 μg/scaffold) (Zhu et al. 2011).

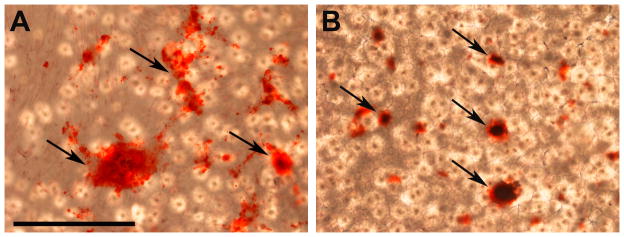

We also investigated whether the percentage weight loss of PCL contributed to the decrease of calcification at 28 days for dynamically cultured cells. The mass of PCL remained the same through 35 days under static conditions. In addition, a previous study from our group has shown that the degradation rate of biodegradable scaffolds decreases under dynamic flow (Agrawal et al. 2000). However, even though no significant mass loss was detected, the chemical degradation process continues and the degradation product of PCL is caproic acid. Acid-based byproducts can dissolve calcium deposits. Previously, we cultured HOBs on 2D PCL films with the addition of 10−10 M Dex in media (Figure 8). Fewer calcium deposits were observed at day-28 compared to those samples at day-21 using Alizarin-Red staining. It’s possible that acid-based byproducts changed the microenvironment of HOBs and its ECM and some calcium was dissolved. This might explain the decrease in calcification (Figure 4) at day-28 on PCL scaffolds.

Figure 8.

Alizarin Red staining of HOBs cultured on PCL films for 21 days (A), and 28 days (B). Media was composed of 10−10 M dexamethasone and without TGF-β1. Scale bar was 1 mm in A and this applies to B.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Under dynamic conditions, cell numbers present in primary human osteoblast cultures on PCL scaffolds increased from day-7 to day-14, and most calcification was induced at day-21. Also under dynamic cultures, doses of TGF-β1 between 5 ng and 50 ng did not show a significant difference in ALP activity, cell numbers, and amount of calcium deposited in HOB cultures. But calcium staining showed that 50 ng of TGF-β1 had higher calcium deposited both on days 21, and 28 under flow conditions compared with 5 ng of loading. More calcification was detected at locations where more cells were present on the scaffolds. Amount of calcium deposited by HOBs on day-28 showed a decrease from their levels on day-21. PCL degradation may be a factor contributing to this loss. The results indicate that cell-induced calcification can be achieved on PCL scaffolds to create a model for total atherosclerotic occlusion with cell-deposited calcium in animal arteries.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Janey Briscoe Center for Cardiovascular Research at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Fluorescent images were generated in the Core Optical Imaging Facility at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, which is supported by NIH-NCI P30 CA54174 (CTRC at UTHSCSA), NIH-NIA P30 AG013319 (Nathan Shock Center), and NIH-NIA P01AG19316.

References

- Abedin M, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Vascular calcification: mechanisms and clinical ramifications. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(7):1161–1170. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133194.94939.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal CM, McKinney JS, Lanctot D, Athanasiou KA. Effects of fluid flow on the in vitro degradation kinetics of biodegradable scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2000;21(23):2443–2452. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos N, Raggi P. Calcification in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6 (11):681–688. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barralet JE, Wallace LL, Strain AJ. Tissue engineering of human biliary epithelial cells on polyglycolic acid/polycaprolactone scaffolds maintains long-term phenotypic stability. Tissue Eng. 2003;9(5):1037–1045. doi: 10.1089/107632703322495673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgen B, Barabino GA. Location of scaffolds in bioreactors modulates the hydrodynamic environment experienced by engineered tissues. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;98(1):282–294. doi: 10.1002/bit.21385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchwey EA, Pollack SR, El-Amin S, Levine EM, Tuan RS, Laurencin CT. Human osteoblast-like cells in three-dimensional culture with fluid flow. Biorheology. 2003;40(1–3):299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera R, Sha Z, Vadakkan TJ, Otero J, Kriegenburg F, Hartmann-Petersen R, Dickinson ME, Chang EC. Proteasome nuclear import mediated by Arc3 can influence efficient DNA damage repair and mitosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(18):3125–3136. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HC, Hu YC. Bioreactors for tissue engineering. Biotechnol Lett. 2006;28(18):1415–1423. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chim H, Ong JL, Schantz JT, Hutmacher DW, Agrawal CM. Efficacy of glow discharge gas plasma treatment as a surface modification process for three-dimensional poly (D,L-lactide) scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;65(3):327–335. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A. Mouse models of atherosclerosis. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323(1):3–10. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facer SR, Zaharias RS, Andracki ME, Lafoon J, Hunter SK, Schneider GB. Rotary culture enhances pre-osteoblast aggregation and mineralization. J Dent Res. 2005;84(6):542–547. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassina L, Visai L, Asti L, Benazzo F, Speziale P, Tanzi MC, Magenes G. Calcified matrix production by SAOS-2 cells inside a polyurethane porous scaffold, using a perfusion bioreactor. Tissue Eng. 2005;11(5–6):685–700. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed LE, Guilak F, Guo XE, Gray ML, Tranquillo R, Holmes JW, Radisic M, Sefton MV, Kaplan D, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Advanced tools for tissue engineering: scaffolds, bioreactors, and signaling. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(12):3285–3305. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachelli CM. Vascular calcification mechanisms. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(12):2959–2964. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000145894.57533.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachelli CM. Inducers and inhibitors of biomineralization: lessons from pathological calcification. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2005;8(4):229–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2005.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grellier M, Bareille R, Bourget C, Amedee J. Responsiveness of human bone marrow stromal cells to shear stress. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3(4):302–309. doi: 10.1002/term.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino V, Causa F, Taddei P, di Foggia M, Ciapetti G, Martini D, Fagnano C, Baldini N, Ambrosio L. Polylactic acid fibre-reinforced polycaprolactone scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29(27):3662–3670. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JJ, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Murine models of atherosclerotic calcification. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9(3):224–228. doi: 10.2174/138945008783755539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Baylink DJ, Lau KH. Fluid flow shear stress stimulates human osteoblast proliferation and differentiation through multiple interacting and competing signal transduction pathways. Bone. 2003;32(3):241–251. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00979-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liegibel UM, Sommer U, Bundschuh B, Schweizer B, Hilscher U, Lieder A, Nawroth P, Kasperk C. Fluid shear of low magnitude increases growth and expression of TGFbeta1 and adhesion molecules in human bone cells in vitro. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2004;112(7):356–363. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-821014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin I, Wendt D, Heberer M. The role of bioreactors in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22(2):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanaswamy M, Wright KC, Kandarpa K. Animal models for atherosclerosis, restenosis, and endovascular graft research. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11 (1):5–17. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie Aronin CE, Cooper JA, Jr, Sefcik LS, Tholpady SS, Ogle RC, Botchwey EA. Osteogenic differentiation of dura mater stem cells cultured in vitro on three-dimensional porous scaffolds of poly(epsilon-caprolactone) fabricated via co-extrusion and gas foaming. Acta Biomater. 2008;4(5):1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser L, Agrawal CM, Polan J, Elliott J, Adams DG, Bailey SR. Implantation of oxygen enhanced, three-dimensional microporous L-PLA polymers: A reproducible porcine model of chronic total coronary occlusion. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67(3):412–416. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke PW, Heinl-Green A, Frass OM, Post MJ, Sato K, Geddes DM, Alton EW. Evaluation of the porcine ameroid constrictor model of myocardial ischemia for therapeutic angiogenesis studies. Endothelium. 2006;13(1):25–33. doi: 10.1080/10623320600660128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Z, Denison TA, Bannister SR, Cochran DL, Liu YH, Lohmann CH, Wieland M, Boyan BD. Osteoblast response to fluid induced shear depends on substrate microarchitecture and varies with time. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;83(1):20–32. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev A, Nili N, Qiang B, Charron T, Butany J, Strauss BH. Human-grade purified collagenase for the treatment of experimental arterial chronic total occlusion. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2005;6(2):65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha Z, Yen HC, Scheel H, Suo J, Hofmann K, Chang EC. Isolation of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe proteasome subunit Rpn7 and a structure-function study of the proteasome-COP9-initiation factor domain. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(44):32414–32423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706276200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha Z, Brill LM, Cabrera R, Kleifeld O, Scheliga JS, Glickman MH, Chang EC, Wolf DA. The eIF3 interactome reveals the translasome, a supercomplex linking protein synthesis and degradation machineries. Mol Cell. 2009;36(1):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shioi A, Mori K, Jono S, Wakikawa T, Hiura Y, Koyama H, Okuno Y, Nishizawa Y, Morii H. Mechanism of atherosclerotic calcification. Z Kardiol. 2000;89(Suppl 2):75–79. doi: 10.1007/s003920070103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikavitsas VI, Bancroft GN, Mikos AG. Formation of three-dimensional cell/polymer constructs for bone tissue engineering in a spinner flask and a rotating wall vessel bioreactor. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62(1):136–148. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Eddington H, Kalra PA. Vascular calcification: lessons from scientific models. J Ren Care. 2009;35(Suppl 1):51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2009.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucosky P, Osorio DF, Brown JB, Neitzel GP. Fluid mechanics of a spinner-flask bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;85(1):34–46. doi: 10.1002/bit.10788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Saito N, Zhang G, Conditt G, McGregor J, Flynn AM, Leahy D, Glennon P, Leon MB, Hayase M. Development of a novel calcified total occlusion model in porcine coronary arteries. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20(6):296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Oyane A, Ikeno F, Lyons JK, Yeung AC. Development of animal model for calcified chronic total occlusion. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;74(3):468–475. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trion A, van der Laarse A. Vascular smooth muscle cells and calcification in atherosclerosis. Am Heart J. 2004;147(5):808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vattikuti R, Towler DA. Osteogenic regulation of vascular calcification: an early perspective. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286(5):E686–696. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00552.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TW, Wu HC, Wang HY, Lin FH, Sun JS. Regulation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells into osteogenic and chondrogenic lineages by different bioreactor systems. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;88(4):935–946. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanni AE. The laboratory rabbit: an animal model of atherosclerosis research. Lab Anim. 2004;38(3):246–256. doi: 10.1258/002367704323133628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Chella R, Ma T. Effects of shear stress on 3-D human mesenchymal stem cell construct development in a perfusion bioreactor system: Experiments and hydrodynamic modeling. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;96(3):584–595. doi: 10.1002/bit.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Bailey SR, Mauli Agrawal C. Engineering calcium deposits on polycaprolactone scaffolds for intravascular applications using primary human osteoblasts. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;5(4):324–336. doi: 10.1002/term.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]