Abstract

Background

To evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of a tannic acid-based medical food, Cesinex®, in the treatment of diarrhea, and to investigate the mechanisms underlying its antidiarrheal effect.

Methods

Cesinex® was prescribed to six children and four adults with diarrhea. Patient records were retrospectively reviewed for the primary outcome. Cesinex® and its major component, tannic acid, were tested for their effects on cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion in mouse. Polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cells) were used to investigate the effects of tannic acid on epithelial barrier properties, transepithelial chloride secretion, and cell viability.

Results

Successful resolution of diarrheal symptoms was reported in nine of ten patients receiving Cesinex®. Treatment of HT29-CL19A cells with clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml) significantly increased transepithelial resistance and inhibited the CFTR-dependent or the calcium-activated Cl− secretion. Tannic acid could also improve the impaired epithelial barrier function induced by TNFα and inhibited the disrupting effect of TNFα on the epithelial barrier function in these cells. CTX-induced mouse intestinal fluid secretion was significantly reduced by administration of Cesinex® or tannic acid. Cesinex® has high antioxidant capacity.

Conclusions

Cesinex® demonstrates an effective and safety profile in treatment of diarrhea. The broad-spectrum antidiarrheal effect of Cesinex® can be attributed to a combination of factors: its ability to improve the epithelial barrier properties, to inhibit intestinal fluid secretion, and the high antioxidant property.

Keywords: Diarrhea, Cesinex®, Tannic acid, Intestinal barrier, Intestinal fluid secretion, Chloride channels

Introduction

Diarrhea is a leading cause of illness and death, especially in the elderly and pediatric population, with 4 billion diarrhea episodes occurring, leading to 4% of all deaths worldwide each year [1]. In the United States, around 300 million episodes of acute diarrhea occur annually, resulting in about 8 million physician visits and more than 900,000 hospitalizations [2].

The use of tannins for treating gastrointestinal diseases can be dated back to the early twentieth century. Albumin tannate tablets have been used to treat diarrhea since 1900’s, and tannin products of various formulations are widely used in Europe nowadays, for instance, a high volume of Gelatin Tannate is prescribed in Spain [3]. Clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of tannins in treatment of acute diarrhea [3, 4], the antidiarrheal effects of tannin albuminate in a patient with Crohn’s disease [5], and the modest protection effects of tannin albuminate (plus ethacridine lactate) against traveler’s diarrhea [6]. Tannins have been shown to inhibit the CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion in Caco-2, FRT, or T84 cells [7–9]. Tannic acid has also been shown to inhibit TMEM16A, a calcium-activated chloride channel (CaCC) [10]. Recent study indicated that tannic acid protects against the adverse intestinal permeability changes during infection by improving the mucosal resistance [11]. In addition, tannic acid appears to exert a protective effect against oxidative stress-induced cell death [12, 13].

Cesinex® is a tannic acid based medical food prescribed in the U.S.A. for treatment of diarrheal diseases. The main ingredients of Cesinex® are a proprietary food grade tannic acid, derived from plants, and dried egg albumen from chicken egg white. Tannic acid used in Cesinex® is a mixture of at least nine compounds with various numbers of gallic acid groups attached to a central glucose or quinic acid core. The main aims of the current study include: (i) to evaluate the efficacy and safety profile of using Cesinex® for treatment of diarrhea in pediatric and adult patients; (ii) to investigate the mechanisms underlying its antidiarrheal effects, especially to study the concentration (dosage)-dependent antidiarrheal property of its major component, tannic acid, and the possible adverse effects associated with the higher dosage.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

The reagents were obtained from the following vendors: Cesinex® and its major component, tannic acid (Hall Bioscience Corp.), human TNFα (BD Biosciences), forskolin and adenosine (Sigma-Aldrich), cupric chloride dihydrate and ascorbic acid (J.T. Baker), Trolox® and ammonium acetate (EMD), ellagic acid, tocopherol and β-carotene (MP Biomedicals), xanophyll and sodium benzoate (Spectrum), gallic acid (Pfaltz & Bauer), other tannic acids (Spectrum, and Konig & Wiegand).

Cell Culture and Animal Experiments

Human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cells) were grown in DMEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under an atmosphere of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Measurement of the Transepithelial Resistance (TER) of Polarized Human Gut Epithelial Cells (HT29-CL19A Cells)

HT29-CL19A cells were grown on Transwell® permeable supports (Corning) and incubated with different concentrations of tannic acid at the apical surface. TERs were measured at varying time points by using a Millicell-ERS Electrical Resistance System (Millipore) and reported as ohms·cm2 by multiplying the resistance with the surface area of the cell monolayers. The resistance of the polycarbonate membrane of transwell (~30 Ω·cm2) was subtracted from all readings.

To test the effect of tannic acid on rescuing the impaired epithelial barrier function caused by exposure to TNFα, the cell monolayers were treated with TNFα (500 U/ml) at the basolateral side for 12 h. Then, tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the apical side of the monolayers. Cells without tannic acid treatment were used as controls. TER were measured at varying time points as described above.

To test the ability of tannic acid on inhibiting the disrupting effect of TNFα on epithelial barrier function in polarized HT29-CL19A cells, tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the apical side of the monolayers and TNFα (500 U/ml) was added to the basolateral side. Cells without tannic acid treatment were used as controls. TER were measured at varying time points as described above.

Inulin Flux Assay

Inulin flux assay was performed as previously described [14]. Briefly, different concentrations of tannic acid were added to the apical side of polarized HT29-CL19A cell monolayers and incubated for 1 h or 6 h at 37 °C. After removing the tannic acid solutions and washing with the culture medium for 3 times, inulin (final concentration: 500 µg/ml) were added to the apical side of cell monolayers and incubated for 1 h. The amount of inulin that fluxed into the basolateral side of the cell monolayers was measured on a Fluostar Omega plate reader (BMG labtech).

Viability Assessment for HT29-CL19A Cells Upon Treatment with Tannic Acid

HT29-CL19A cells were treated with different concentrations of tannic acid for varying period of time and then cultured in normal medium. After 12 h, cells were detached by using trypsin-EDTA. The cell suspensions were centrifuged (1000 g for 10 min), and the cell viability was assessed by using trypan blue exclusion method.

Mouse Intestinal Fluid Secretion Measurements

The mouse model for diarrhea was followed with modifications [15]. C57BL/6J mice (body weight: 20–22 g) were fasted for 24 h and then anesthetized by using pentobarbital (60 mg/kg). Mouse body temperature was maintained between 36–38 °C during surgery. After making a small abdominal incision, 3 closed mid-jejunal loops (2–3 cm in length) were generated by sutures. The loops were injected with 100 µl of the following solutions: PBS, PBS containing CTX (2 µg) with or without tannic acid (0.15 mg/loop), or PBS containing CTX (2 µg) with Cesinex® (6 µl /loop). Abdominal incisions were closed with sutures, and the mice were allowed to recover. After 6 h, the mice were anesthetized. The intestinal loops were collected and the net fluid secretion was quantified by measuring the length/weight ratio of the loop. The photographs of the loops were taken by using a digital camera.

Short-circuit Currents (Isc) Measurements (Ussing Chamber Experiments)

HT29-CL19A cells were grown on Costar Transwell® permeable supports until they reached a resistance of more than 800 Ω and then mounted in an Ussing chamber. Short-circuit currents (Isc) were measured as previously reported [15]. Briefly, the cells were bathed in Ringer’s solution (mM) (Basolateral: 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.36 K2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 4.2 NaHCO3, 10 Hepes, 10 glucose, pH 7.2, [Cl−] = 149), and low Cl− Ringer’s solution (mM) (Apical: 133.3 Na-gluconate, 5 K-gluconate, 2.5 NaCl, 0.36 K2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 5.7 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 4.2 NaHCO3, 10 Hepes, 10 mannitol, pH 7.2, [Cl−] = 14.8) at 37°C, gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. All reagents were added at the apical side of the cell monolayers.

Antioxidant Capacity Measurements (CUPRAC assay)

In this assay, the antioxidant capability of the reagents was measured by their ability to reduce nCu(Nc)22+ to nCu(Nc)2+ [16]. Briefly, the Cesinex® suspension was diluted 25-fold with acetonitrile/water (70%, v/v) to precipitate the protein and solubilize the tannic acid. Five milliliter (5.0 ml) of the filtered solution was diluted to 100 ml with deionized water to produce the test solution. Samples of other antioxidant materials were prepared in ethanol (0.5 mg/ml) and then diluted 13-fold with deionized water. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Clinical Patient Record Review

Cesinex® was prescribed to six children (18 months – 8 years old) and four adults (55–71 years old) with diarrhea. None of the patients had fever over 101.5 °F or dysentery (bloody diarrhea). Cesinex® was dosed according to the product labeling using a weight-based (mg/kg) dosing regimen. The pediatric patients were treated in a hospital in-patient setting. The adults were treated through community based outpatient practices. Fresh stool obtained at admission of the pediatric patients was tested for bacterial pathogens and rotavirus by using standard microbiologic methods. Specific causes for diarrhea were found in two pediatric patients who tested positive for rotavirus. In the remaining eight patients, no specific cause was found and a presumptive diagnosis of viral gastroenteritis was given. Data was gathered via a retrospective review of patient records.

Statistical Analysis

The data were presented as the mean ± S.E., with n for the indicated number of experiments. Statistical analyses were performed by using Student's t test or one-way ANOVA. Values of *P<0.05, **P<0.01, or ***P<0.001 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Primary Outcomes of the Clinical Record Review

To assess the efficacy and safety of using Cesinex® in the treatment of diarrhea, Cesinex® was prescribed to ten patients (four adults and six pediatrics). Among these patients, two pediatric patients were tested positive for rotavirus. Most patients took Cesinex® 3–4 times per day for 2–3 days. The average number of doses taken was 9.2 with a range from 3 to 20. Side effects reported were rash and itching in one pediatric patient and gagging in another pediatric patient, no other patients reported any side effects. The primary outcome reported was "diarrheal symptoms resolved" in 9 of 10 patients (Table 1; Note: the single patient who did not report ‘diarrheal symptoms resolved’ withdraw from the study due to rash and itching as mentioned above).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and outcome of all patients treated with Cesinex®

| Pediatric patients | Adult patients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| # BM before | 10–15 | 8–12 | >4 | >4 | 3–4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | 3 | 3–4 |

| # BM after | 4–6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2–3 | ≤1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| # doses | 20 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 16–20 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 4 |

| Dose frequency/day | 3–4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3–4 | 4 | 4 | 4–6 | 4 |

| Days of taking Cesinex® | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Symptoms resolved | Y | Y | Y | Y | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Side effects | Gagging | N | N | N | Rash | N | N | N | N | N |

| Effectiveness (1–5) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

Note: Y denotes Yes; N denotes No. N/A: not applicable. The patient withdrew from the studydue to rash.

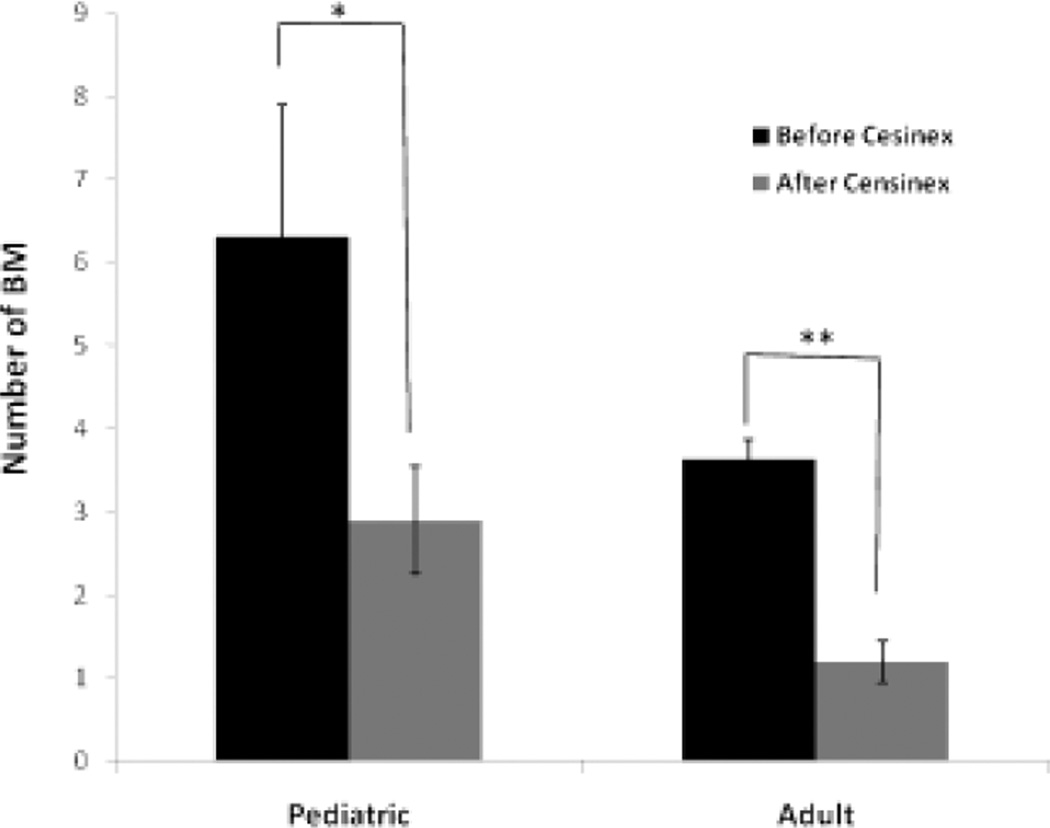

The average bowel movement (BM) number before taking Cesinex® was 6.3 per day (with a range of 3 to 15) for pediatric patients and 3.5 per day (with a range of 3 to 4) for adult patients. After taking Cesinex®, the average BM number reduced to 2.9 per day (with a range of less than 1 to 6) for pediatric patients and 1.2 (with a range of less than 1 to 2) for adult patients (Table 1). These differences are statistically significant (Fig. 1). In addition to the reduced BM number, the patients also reported the reduced volume of stools.

Fig. 1.

Number of bowel movement (BM) per day for all patients before and after administration of Cesinex®. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.; n = 5 for pediatric patients; n = 4 for adult patients. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01.

In brief, our clinical results demonstrate that Cesinex® is effective in managing diarrhea and has a good safety profile.

Clinically Relevant Concentrations of Tannic Acid Improves the Intestinal Epithelial Cell Barrier Function

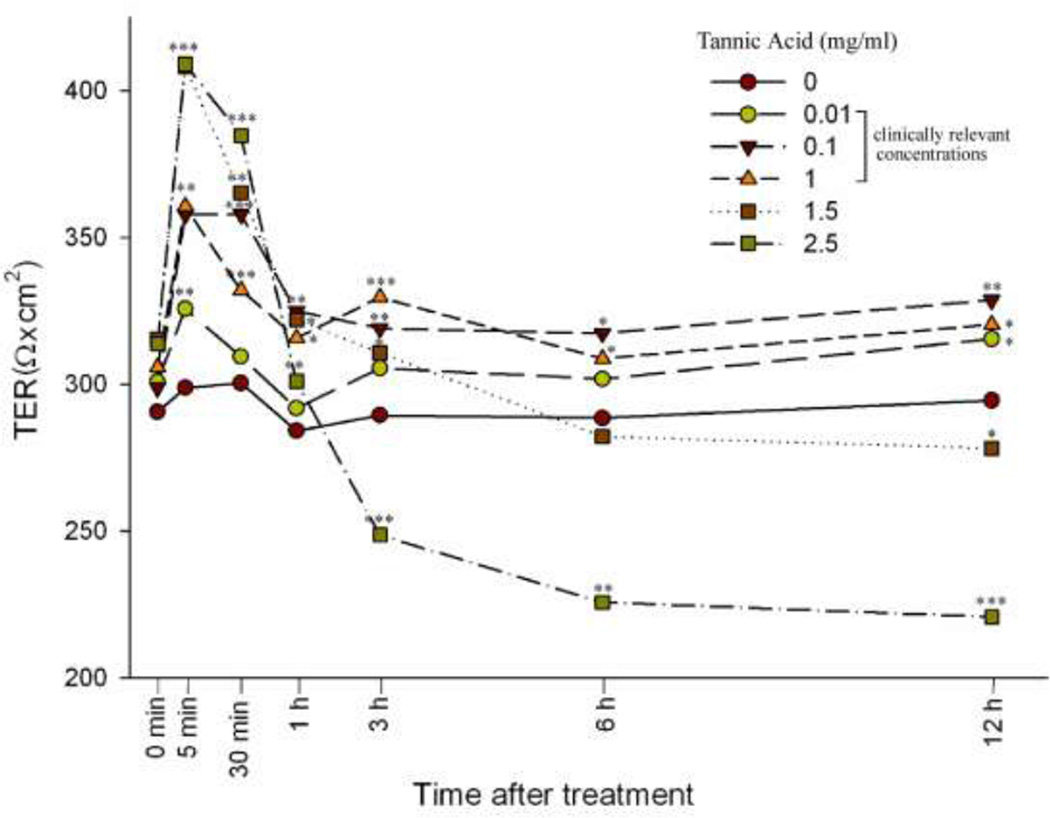

Disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier occurs in many intestinal diseases. It has been shown that epithelial barrier dysfunction is critical to the pathogenesis of diarrheal diseases. Permeability of the intestinal epithelial barrier is regulated in response to physiological and pathophysiological stimuli. Acute tight junction regulation has been suggested to play a critical role in the development of diarrhea secondary to T cell activation and cytokine release [17–19]. To investigate whether Cesinex® has any regulatory roles on the intestinal epithelial barrier functions, human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cells) were seeded on Transwell® permeable supports and then treated with different concentrations of tannic acid (the major component of Cesinex®) at the apical surface. The epithelial cell barrier function was monitored by measuring the transepithelial resistance (TER), an index for the paracellular barrier function and integrity of tight junction, at varying time points after treatment with tannic acid. Cesinex® was not directly used for this assay because it is not totally soluble in the assay buffer and only forms a suspension. As shown in Fig. 2, for the control cells (without tannic acid treatment), the TER values remained at a steady level. When the cells were treated with low concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml; please be noted that this concentration range is within a clinical dosage of Cesinex®, thus is referred to as ‘clinically relevant concentrations’ in this study), the TERs were significantly increased and kept at high levels for 12 h. However, when the cells were treated with higher concentrations of tannic acid (≥2.5 mg/ml; please be noted that these concentrations are higher than that in a clinical dosage of Cesinex®), the TERs peaked within 5 min but then kept decreasing. After 1 h, the TERs started to drop below the TER values of the control cells (Fig. 2). When tannic acid was removed from the apical side after 1 h or 6 h incubation and the cells were cultured in normal medium for 12 h, we found that the cells treated with the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml) could recover the normal TER values; whereas the cells treated with higher concentrations of tannic acid (≥2.5 mg/ml) could not recover the normal TER values. Our results suggest that treatment of the cells with the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid can improve the intestinal epithelial cell barrier function, but that further increase of the dosage would cause adverse effects to the intestinal epithelial cell barrier function, especially when treated for extended period of time (e.g. > 1 h).

Fig. 2.

The clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml) improves the epithelial barrier function in polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cell monolayers). Polarized HT29-CL19A cells were exposed to different concentrations of tannic acid at the apical surface. Transepithelial Resistances (TER) were measured at the time points indicated. n = 3. Error bars are not shown for clarity because they are obscured by the symbols. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with controls.

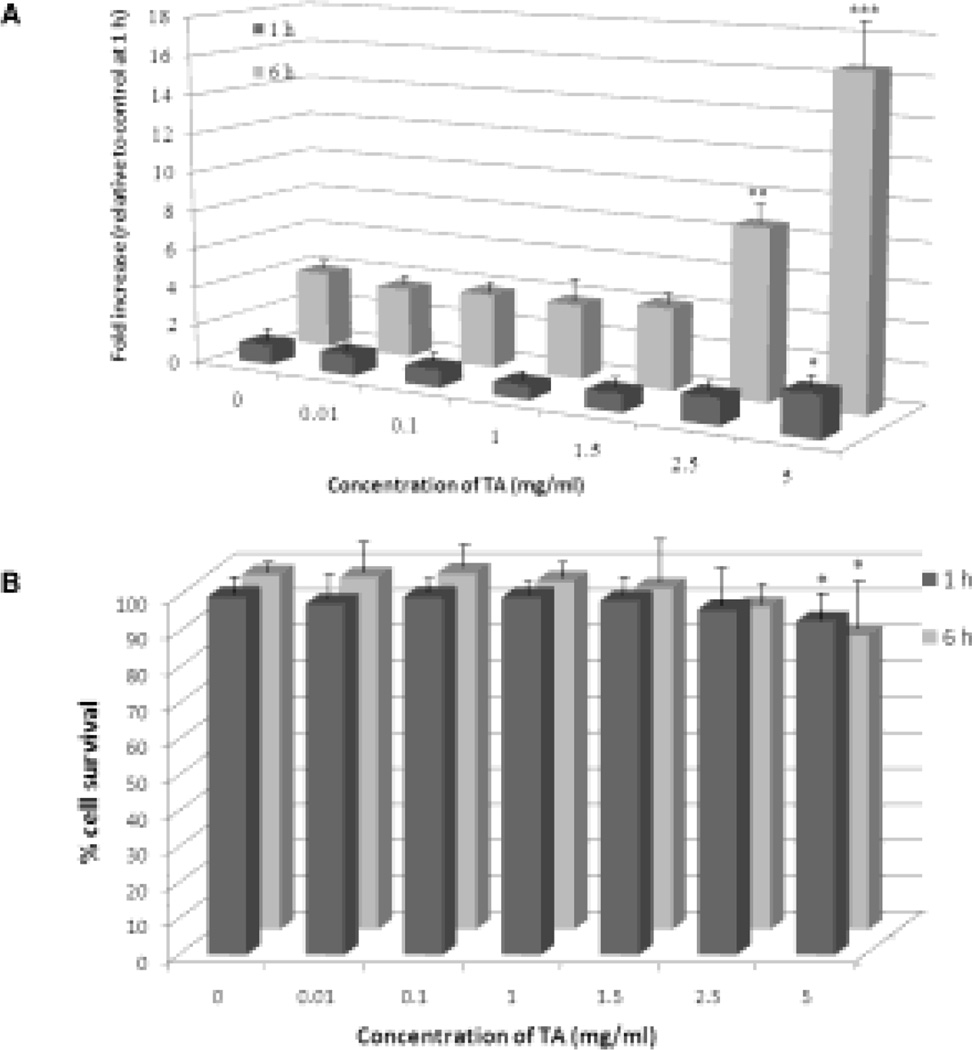

To further investigate the effect of tannic acid on the integrity of tight junction for human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cells), we monitored the diffusion of a small molecule tracer, inulin, from the apical side of the cell monolayers to the basolateral side upon treatment of the cells with different concentrations of tannic acid for 1 h or 6 h. We found that compared with the control cells (without tannic acid treatment), the inulin permeability in cells treated with the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml) was slightly decreased (Fig. 3A). However, the inulin permeability in cells treated with higher concentrations of tanic acid (≥2.5 mg/ml) was significantly increased, especially when treated for longer time (6 h) (Fig. 3A). The data are consistent with the results from the TER measurements, indicating that the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml) can improve the intestinal epithelial barrier function, and that higher concentrations of tannic acid (≥2.5 mg/ml) cause adverse effects.

Fig. 3.

Dose- and time-dependent effect of tannic acid treatment on the viability and the epithelial integrity of human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cell monolayers). (A) The integrity of the cell monolayers was monitored by using Inulin flux assay. Inulin permeability was measured after the cells had been treated with varying concentrations of tannic acid for 1 h or 6 h. The data are presented as the increase (in folds) in the inulin permeability compared to that of untreated cells after 1 h incubation. (mean ± S.E; n = 3) * P<0.05, ** P < 0.01, ***P<0.001. The results show that the inulin permeability was slightly decreased when the cells were treated with the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml), and that when the cells were treated with higher concentrations of tannic acid (> 2.5 mg/ml), the Inulin permeability significantly increased, suggesting that higher concentrations of tannic acid had adverse effect on the integrity of the cell monolayers. (B) HT29-CL19A cells were treated with different concentrations of tannic acid for 1 h or 6 h and then cultured in normal medium. After 12 h, cells viability was assessed by using trypan blue staining. The data are presented as percentage (%) of cell survival to that of untreated cells (mean ± S.E; n = 4). The results show that the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml) did not cause cytotoxicity to cells. However, higher concentrations of tannic acid (> 2.5 mg/ml) caused cells cytotoxicity. TA: tannic acid.

One of the possible reasons for the adverse effects observed for higher concentrations of tannic acid on the intestinal epithelial barrier function might be the cytotoxicity which imposed. To confirm this, we measured the viability of HT29-CL19A cells upon treatment with different concentrations of tannic acid for 1 h or 6 h by using trypan blue exclusion assay. As shown in Fig. 3B, compared with the control cells (without tannic acid treatment), the cells treated with the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01– 1 mg/ml) did not show cytotoxicity; whereas the cells treated with higher concentrations of tannic acid (≥2.5 mg/ml) showed cytotoxicity, especially when treated for longer time (6 h).

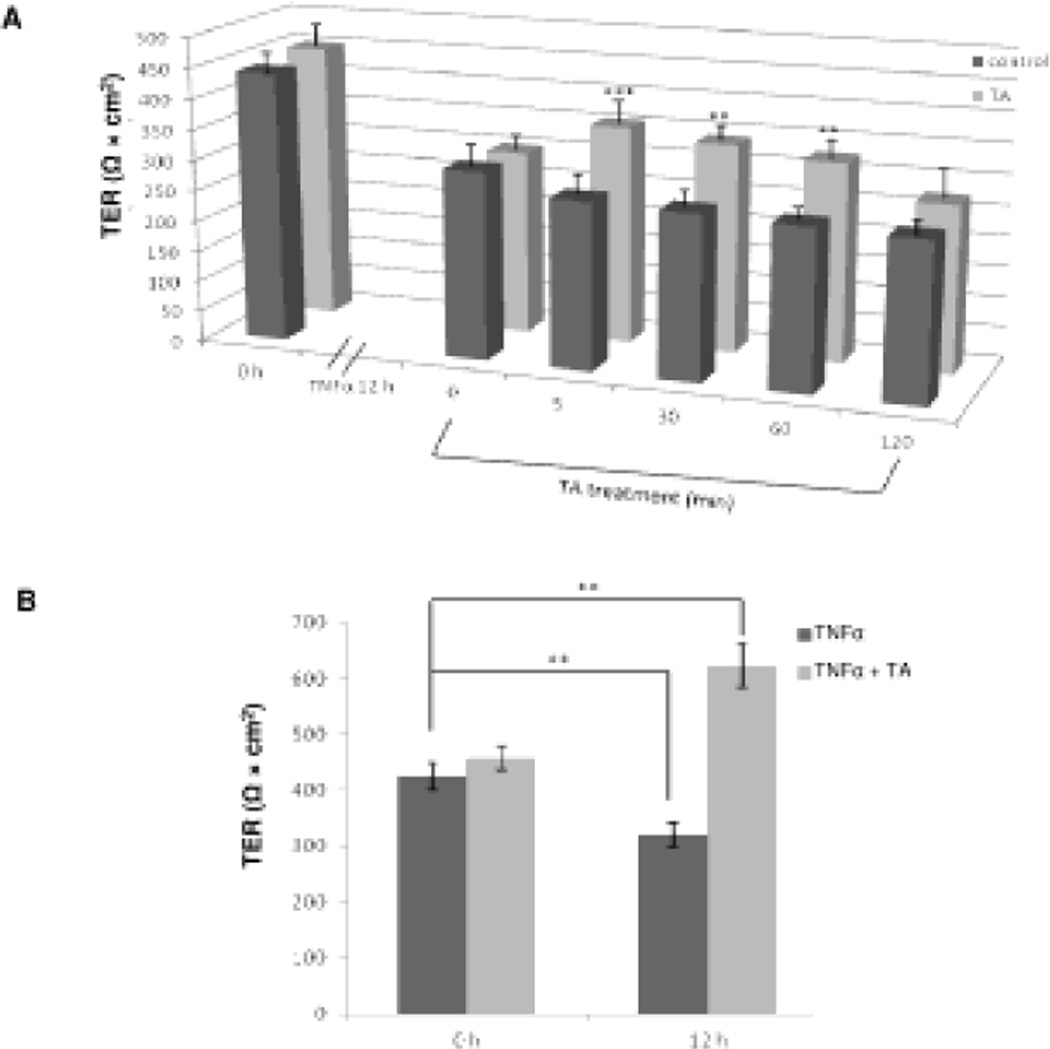

We also tested whether clinically relevant concentration of tannic acid could improve the impaired epithelial barrier function in polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cell monolayers). To perform this, we used human tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) to disrupt the epithelial barrier function and tested the rescuing effect of tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml). TNFα is a pro-inflammatory cytokine and has been shown to disrupt the epithelial barrier function in vitro and in vivo [20, 21]. The cell monolayers were treated with TNFα (500 U/ml) at the basolateral surface for 12 h. Then, tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the apical surface of the monolayers. Cells without tannic acid treatment were used as controls. As shown in Fig. 4A, TNFα impaired the epithelial barrier function in these cell monolayers. Treatment with tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) significantly improved the epithelial barrier function.

Fig. 4.

Clinically relevant concentration of tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) improves the impaired epithelial barrier function induced by TNFα in polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cell monolayers). (A) Tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) improves the impaired epithelial barrier function induced by TNFα in polarized HT29-CL19A cells. The cell monolayers were treated with TNFα (500 U/ml) at the basolateral side for 12 h. Then, tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the apical side of the monolayers. Cells without tannic acid treatment were used as controls. TER were measured at the time points indicated. The data are presented as the mean ± S.E; n = 9. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with the controls. (B) Tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) prevents the adverse disrupting effect of TNFα on the epithelial barrier function in polarized HT29-CL19A cells. Tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the apical side of the monolayers and TNFα (500 U/ml) was added to the basolateral side. Cells without TA treatment were used as controls. The data are presented as the mean ± S.E; n = 9. **P<0.01 compared with the control. TA: tannic acid

We further tested whether tannic acid of clinically relevant concentration could inhibit the disrupting effect of TNFα on epithelial barrier function in polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cell monolayers). To perform this, tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the apical surface of the cell monolayers and TNFα (500 U/ml) was added to the basolateral surface. Cells without tannic acid treatment were used as controls. Our results demonstrate that tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) significantly inhibited the disrupting effect of TNFα on the epithelial barrier function in these cells (Fig. 4B).

Taken together, our results demonstrate that: (1) the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01– 1 mg/ml), and thus Cesinex®, can improve the epithelial barrier properties in polarized HT29-CL19A cells; (2) clinically relevant concentration of tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) can improve the impaired epithelial barrier function induced by TNFα in polarized HT29-CL19A cells; (3) tannic acid (0.5 mg/ml) can also inhibit the adverse disrupting effect of TNFα on the epithelial barrier function in polarized HT29-CL19A cells. All these effects would be beneficial for the treatment of diarrhea; (4) further increase in the tannic acid concentrations causes adverse effects on the cell viability.

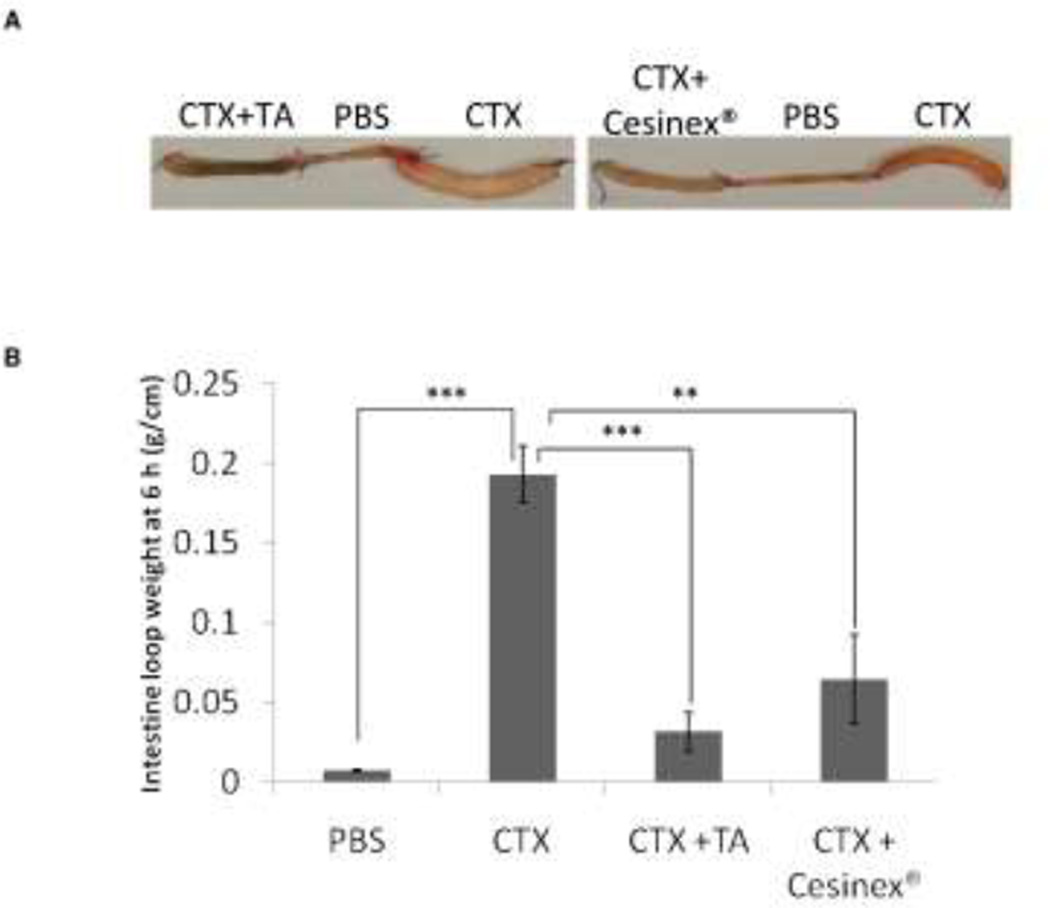

Cesinex® and Clinically Relevant Concentrations of Tannic Acid Inhibit CTX-induced Mouse Intestinal Fluid Secretion

In this study, we tested the inhibitory effects of Cesinex® and the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid on CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion by using a mouse closed-loop model. The fluid secretion was quantified by measuring the weight/length ratio of the loop before and after injecting solutions containing CTX with or without Cesinex® (or tannic acid). As shown in Fig. 5, the average weight/length ratio for loops injected with PBS, PBS containing CTX (2 µg/loop), PBS containing CTX (2 µg/loop) and tannic acid (0.15 mg/loop), or PBS containing CTX (2 µg/loop) and Cesinex® (6 µl/loop) were 0.0071±0.001, 0.193±0.018, 0.031±0.013, 0.064±0.028, respectively. The data demonstrated that concomitant intraluminal administration of Cesinex® or the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid significantly reduced the fluid accumulation in CTX-treated loops (66.8% by using Cesinex®, P <0.01; 83.9% by using tannic acid, P <0.001). The mice that received tannic acid or Cesinex® at 30 min post-exposure to CTX also showed significant decrease in intestinal fluid secretion. In brief, our results clearly demonstrate that Cesinex® and the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid can inhibit CTX-induced mouse intestinal fluid secretion.

Fig. 5.

Cesinex® and the clinically relevant concentration of tannic acid inhibit CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion in a mouse closed-loop model. (A) Representative photographs of the isolated mouse mid-jejunal loops 6 h after luminal injection of 100 µl of the following solutions: PBS, PBS containing CTX (2 µg), PBS containing CTX (2 µg) and tannic acid (0.15 mg/loop), or PBS containing CTX (2 µg) and Cesinex® (6 µl). (B) Summary of the weight/length ratios of the loops calculated from the experiments as represented in (A). The data are presented as the mean ± S.E; n = 4. ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001. TA: tannic acid.

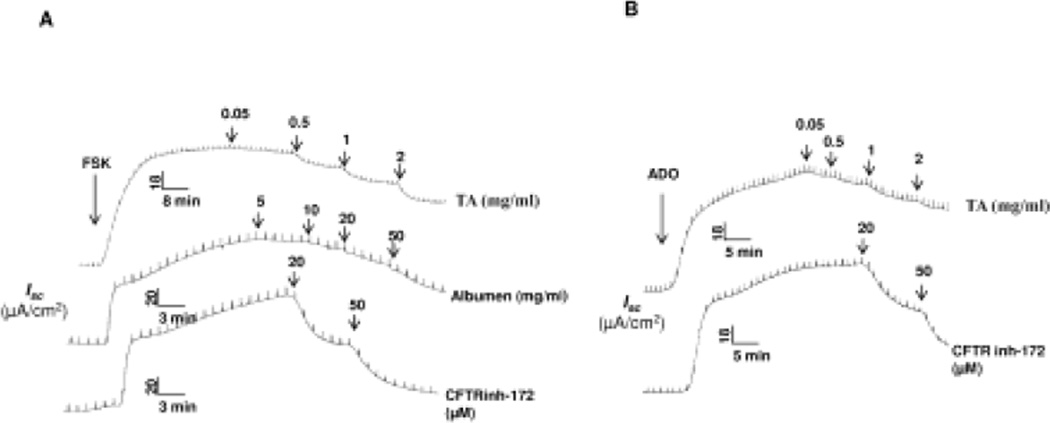

The Clinically Relevant Concentrations of Tannic Acid Inhibits CFTR-mediated Transepithelial Chloride Secretion in Polarized Human Gut Epithelial Cells (HT29-CL19A Cells)

CTX-induced fluid secretion has been reported to be directly proportional to the expression level of CFTR Cl− channel [15, 22, 23]. To further delve into the mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effects of Cesinex® on CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion, we first measured the effect of the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid on CFTR-dependent transepithelial Cl− secretion in polarized HT29-CL19A cells. Cesinex® was not directly used for the assay because it is not totally dissolved in the assay buffer and forms a suspension. Briefly, HT29-CL19A cells were seeded on Transwell® permeable supports and the inserts were mounted in a Ussing chamber for measuring CFTR-dependent short-circuit currents (Isc). In these studies, CFTR channel function was activated by using forskolin (FSK) or adenosine (ADO). A specific CFTR channel inhibitor, CFTRinh-172, was used to verify that the Isc responses observed were indeed CFTR-dependent, and also used as a positive control for tannic acid. As shown in Fig. 6, tannic acid inhibited the CFTR-mediated Isc in a dose-dependent manner. Since it has been reported that egg albumen contains high amounts of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), and that LPA inhibits CTX-induced secretory diarrhea through CFTR-dependent protein-protein interactions (22), we also tested the effect of albumen (another component of Cesinex®) on CFTR-mediated Isc. As expected, we observed that albumen also inhibited the CFTR-mediated Isc, although to a less extent compared to tannic acid (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

The clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid and albumen inhibit CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion in polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cell monolayers). Data shown are representative traces of 3–5 separate experiments. (A) Forskolin (FSK, 15 µM) was used to activate CFTR channel. (B) Adenosine (ADO, 100 µM) was used to activate CFTR channel. A specific CFTR channel inhibitor, CFTRinh-172, was used as a positive control, and to verify the responses observed are CFTR-dependent.

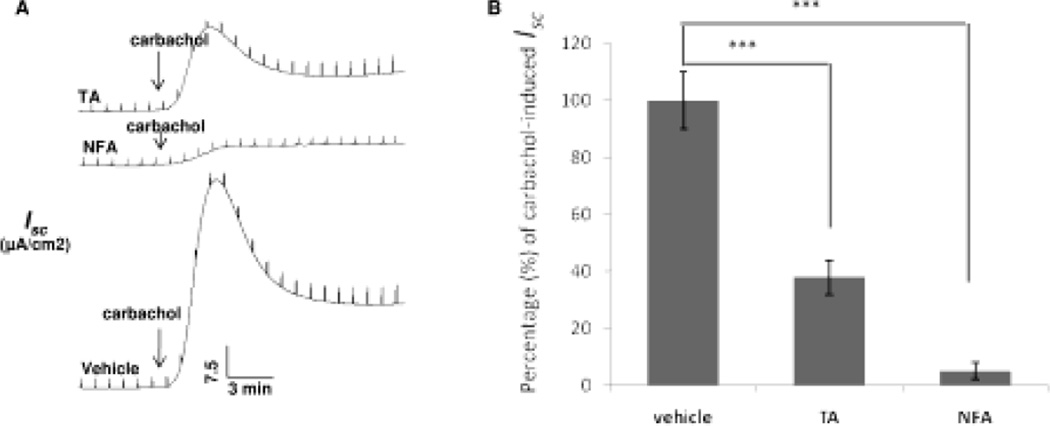

The Clinically Relevant Concentrations of Tannic Acid Inhibits the Calcium-activated Chloride Secretion in Human Gut Epithelial Cells (HT29-CL19A Cells)

In addition to CFTR-dependent pathway, intestinal chloride secretion is also activated by a calcium-mediated signaling cascade (CaCC). To investigate whether the clinically relevant concentration of tannic acid plays any role in the calcium-activated Cl− secretion, we used carbachol (100 µM), a muscarinic receptor agonist that elevates intracellular calcium levels, to stimulate the calcium-activated chloride secretion in polarized HT29-CL19A cells. Niflumic acid (NFA, an inhibitor of CaCCs) was used as a control for the studies. As shown in Fig. 7, carbachol induced Cl− secretion in these cells. Pretreatment of the cells with the clinically relevant concentration of tannic acid (1 mg/ml) significantly inhibited the carbachol-induced chloride currents, suggesting that at this concentration tannic acid inhibits the calcium-activated Cl− channel.

Fig. 7.

The clinically relevant concentration of tannic acid inhibits the calcium-activated chloride secretion in polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cell monolayers). (A) Representative traces of chloride secretion currents induced by carbachol (10 µM) after the cells had been pretreated with tannic acid (1 mg/ml), or 100 µM niflumic acid (an inhibitor for calcium-activated chloride channels), or vehicle for 5 min. (B) Summary of the data from experiments as represented in (A). The data are presented as percentage (%) of Isc to the carbachol-induced Isc (mean ± S.E.; n=4). *** P<0.001. TA: tannic acid; NFA: niflumic acid.

Cesinex® Shows High Antioxidant Capacity

We tested the antioxidant capacity of Cesinex® and tannic acid by using CUPRAC assay. Gallic acid and other antioxidants such as β-carotene, xanthophyll and tocopherol were also tested (Table 2). The results showed that Cesinex® has a high TEAC (the Trolox® Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity) value of 4.03, indicating its high antioxidant capacity. Tannic acid was also found to have high antioxidant capacity with a TEAC value of 3.95. Gallic acid and ellagic acid were found to have higher TEAC values than tannic acids, probably because hydroxyl groups in these molecules have less steric hindrance. The other antioxidants, β-carotene, xanthophyll and tocopherol, had very low TEAC values when measured in this assay. The high antioxidant capacity of Cesinex® would provide beneficial anti-inflammatory effect in the therapy of diarrhea.

Table 2.

The antioxidant capacity of Cesinex®, tannic acid, and other antioxidants measured by CUPRAC assay

| Compounds | TEAC/g |

|---|---|

| Tannic acid | 3.95 |

| Cesinex® | 4.03 |

| Gallic Acid | 4.98 |

| Epicatechin | 3.52 |

| Ellagic Acid | 4.32 |

| Sodium Benzoate | 0.01 |

| β-Carotene | 0.07 |

| Ascorbic Acid | 1.63 |

| Xanthophyll | 0.05 |

| Tocopherol | 0.27 |

Discussion

Diarrhea poses a serious public health problem and intensive efforts have been made to develop simple, safe and cost-effective approaches to treat this disease. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the efficacy and safety profile of using a tannic acid based medical food, Cesinex®, to treat diarrheal disease in pediatric and adult patients, and to investigate the mechanisms underlying its antidiarrheal effects. In this regard, we especially aimed to study the concentration (dosage)-dependent antidiarrheal property of tannic acid (the major component of Cesinex®), and the possible adverse effects associated with the higher dosage. Cesinex® demonstrated significant and consistent (P<0.05 in pediatric patients and P<0.001 in adult patients) reduction in 72-hour stool output, total stool output and duration of diarrhea. Diarrheal symptoms were successfully resolved in 9 of the 10 patients. Also importantly, Cesinex® demonstrated a good safety profile.

In mechanistic studies, our data demonstrate that the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml) can significantly increase the transepithelial resistance (TER) of the polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cells), suggesting that at this concentration range tannic acid (and thus a prescribed dosage of Cesinex®) have the capability of improving the intestinal epithelial barrier properties. There are two potential pathways for passive permeation across the intestinal epithelium: the transcellular pathway and the paracellular pathway. The resistance to passive ion flow through the transcellular pathway is on the order of 1,000–10,000 Ω·cm2 [24]. In contrast, the resistance of mammalian small intestinal epithelium is 50–90 Ω·cm2, suggesting that the paracellular pathway is the major site for passive transepithelial permeation [25]. Tight junction is a major component of the epithelial barrier. Disrupting the tight junction of the intestinal epithelium increases intestinal paracellular permeability and often leads to diarrhea in gastrointestinal diseases. It is thus intuitively obvious that improving epithelial barrier function can significantly reduce fluid secretion and thus be beneficial in the therapy of diarrheal disease. Recent studies have suggested a critical role of acute tight junction regulation in the pathogenesis of diarrhea [17–19]. Our results demonstrate that the clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml) can rapidly increase TER of the human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cells) which peaks within 5 min and can keep at high levels for 12 h. However, when the cells were treated with tannic acid at concentrations higher than the clinically relevant concentrations (e.g., ≥2.5 mg/ml), after peaked, the TER kept decreasing and dropped below the TER value of the control cells in 1 h, suggesting that high concentrations of tannic acid might be toxic to the cells. Viability measurement of the cells treated with different concentrations of tannic acid show that high concentration of tannic acid treatment (e.g., ≥ 2.5 mg/ml) for longer time (e.g., > 1 h) was indeed cytotoxic to the cells. However, when the cells were treated with clinically relevant concentrations of tannic acid (0.01–1 mg/ml), the cells were viable. Given that the transit time in the small intestine for a prescribed dosage of drug is reported to be 3±1 h regardless of the type of subjects in human [26], when taking a prescribed dose of Cesinex® (which corresponds to tannic acid concentration in the range of 0.01–1 mg/ml), it is unlikely to accumulate high concentration of tannic acid in gastrointestinal system. Conversely, at this dosage, tannic acid can improve the intestinal epithelial barrier function, and thus be beneficial to the therapy of diarrhea. This notion is further supported by the observations that the clinically relevant concentration of tannic acid (e.g., 0.5 mg/ml) can indeed improve the impaired epithelial barrier function due to TNFα exposure in polarized HT29-CL19A cells, and that it can inhibit the disrupting effect of TNFα on the epithelial barrier function in these cells.

In this study, we tested the inhibitory effects of Cesinex® and its major component, tannic acid (at the clinically relevant concentration), on CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion by using a mouse closed-loop model. We also tested the inhibitory effect of tannic acid on transepithelial Cl− secretion in polarized human gut epithelial cells (HT29-CL19A cells). Our results demonstrate that Cesinex® and tannic acid (at the clinically relevant concentrations: 0.01–1 mg/ml) significantly inhibit CTX-induced mouse intestinal fluid secretion, and that tannic acid inhibits both CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion and calcium-activated Cl− secretion in HT29-CL19A cells. Interestingly, Egg albumen, another component of Cesinex® which is used to help minimize the breakdown of tannic acid in the stomach so that it can reach the intestines, was also found to inhibit CFTR-dependent Cl− secretion in polarized HT29-CL19A cells, though to a less extent compared to tannic acid (Fig. 6A). It has been shown that egg albumen contains high amounts of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), and that LPA inhibits CTX-induced secretory diarrhea through CFTR-dependent protein-protein interactions [22]. Our results suggest that formulation of tannic acid with egg albumen provides additional beneficial effect to improve its anti-diarrheal properties.

Tannins are antioxidants characterized by their strong free radical scavenging activities and anti-inflammatory properties. It has been reported that the antioxidant defense system in both the small and large intestine in rat is impaired in early chronic diarrhea [27]. In addition, Tannic acid has been suggested to exert a protective effect against oxidative stress-induced cell death and is effective in preventing and treating intestinal inflammation and injury [28, 29]. In this study, we measured the antioxidant capacity of Cesinex® and its major component tannic acid. Our results show that both of them have high antioxidant capacities, which would provide anti-inflammatory effects in the therapy of diarrhea.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the tannic acid based medical food, Cesinex®, is effective in managing diarrhea and has a good safety profile. Since it is a medical food, it can be used in combination with other prescriptions, oral rehydration solutions, or probiotic dietary supplements. Moreover, as a palatable formulation, Cesinex® has the advantages of improving compliance and minimizing spillage or waste during administration, especially for pediatric patients. In mechanistic studies, our results suggest that the antidiarrheal effects of Cesinex® can be largely attributed to the ability of its major component, tannic acid, to improve intestinal epithelial barrier function, to inhibit intestinal fluid secretion through the CFTR-dependent pathway and calcium-mediated signaling pathways, and also its high antioxidant property. The presence of egg albumen also increases its anti-diarrheal effects. These factors work in concert to enable the broad-spectrum anti-diarrheal effects of Cesinex®.

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by U.S.A. National Institutes of Health (DK074996 and DK080834 to APN). Hall Bioscience partially funded the mechanistic studies (for purchasing reagents and materials needed for the experiments).

Abbreviations

- ADO

adenosine

- BM

bowel movement

- CaCC

the calcium-activated chloride channel

- CFTR

the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CTX

cholera toxin

- FSK

forskolin

- NFA

Niflumic acid

- TA

tannic acid

- TEAC

the Trolox® Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity

- TER

transepithelial resistance

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

Contributor Information

Aixia Ren, Department of Physiology, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, 894 Union Avenue, 415 Nash Research Building, Memphis, TN 38163, U.S.A. Tel.: (901) 448-3507, Fax: (901) 448-7126, aren@uthsc.edu.

Weiqiang Zhang, Department of Physiology, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, 894 Union Avenue, 415 Nash Research Building, Memphis, TN 38163, U.S.A. Tel.: (901) 448-3507, Fax: (901) 448-7126, wzhang16@uthsc.edu.

Hugh Greg Thomas, Hall Bioscience Corporation, 5659 Southfield Drive Suite A, P. O. Box 7788, Flowery Branch, GA 30542, U.S.A. Tel.: (678) 450-9187, gthomas@kielpharm.com.

Amy Barish, Hall Bioscience Corporation, 5659 Southfield Drive Suite A, P. O. Box 7788, Flowery Branch, GA 30542, U.S.A. Tel.: (770) 617-1621, amybarish@comcast.net.

Stephen Berry, Hall Bioscience Corporation, 5659 Southfield Drive Suite A, P. O. Box 7788, Flowery Branch, GA 30542, U.S.A. Tel.: (770) 530-1742, sberry1966@aol.com.

Jeffrey S. Kiel, Hall Bioscience Corporation, 5659 Southfield Drive Suite A, P. O. Box 7788, Flowery Branch, GA 30542, U.S.A. Tel.: (678) 450-9187. jk@kielpharm.com

Anjaparavanda P. Naren, Department of Physiology, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, 894 Union Avenue, 426 Nash Research Building, Memphis, TN 38163, U.S.A. Tel.: (901) 448-3137, Fax: (901) 448-7126, anaren@uthsc.edu.

References

- 1.Yan F, Polk DB. Probiotics as functional food in the treatment of diarrhea. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:717–721. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000247477.02650.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thielman NM, Guerrant RL. Clinical practice. Acute infectious diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:38–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp031534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteban Carretero J, Durban Reguera F, Lopez-Argueta Alvarez S, Lopez Montes J. A comparative analysis of response to vs. ORS + gelatin tannate pediatric patients with acute diarrhea. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:41–48. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082009000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeb H, Vandenplas Y, Wursch P, Guesry P. Tannin-rich carob pod for the treatment of acute-onset diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:480–485. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plein K, Burkard G, Hotz J. Treatment of chronic diarrhea in Crohn disease. A pilot study of the clinical effect of tannin albuminate and ethacridine lactate. Fortschr Med. 1993;111:114–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziegenhagen DJ, Raedsch R, Kruis W. Traveler's diarrhea in Turkey. Prospective randomized therapeutic comparison of charcoal versus tannin albuminate/ethacridine lactate. Med Klin (Munich) 1992;87:637–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabriel SE, Davenport SE, Steagall RJ, Vimal V, Carlson T, Rozhon EJ. A novel plant-derived inhibitor of cAMP-mediated fluid and chloride secretion. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G58–G63. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.1.G58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wongsamitkul N, Sirianant L, Muanprasat C, Chatsudthipong V. A plant-derived hydrolysable tannin inhibits CFTR chloride channel: a potential treatment of diarrhea. Pharm Res. 2010;27:490–497. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-0040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuier M, Sies H, Illek B, Fischer H. Cocoa-related flavonoids inhibit CFTR-mediated chloride transport across T84 human colon epithelia. J Nutr. 2005;135:2320–2325. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.10.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namkung W, Thiagarajah JR, Phuan PW, Verkman AS. Inhibition of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels by gallotannins as a possible molecular basis for health benefits of red wine and green tea. FASEB J. 2010;24:4178–4186. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-160648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Ampting MT, Schonewille AJ, Vink C, Brummer RJ, van der Meer R, Bovee-Oudenhoven IM. Damage to the intestinal epithelial barrier by antibiotic pretreatment of salmonella-infected rats is lessened by dietary calcium or tannic acid. J Nutr. 2010;140:2167–2172. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.124453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CH, Liu TZ, Chen CH, et al. The efficacy of protective effects of tannic acid, gallic acid, ellagic acid, and propyl gallate against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress and DNA damages in IMR-90 cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;518:962–968. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tikoo K, Tamta A, Ali IY, Gupta J, Gaikwad AB. Tannic acid prevents azidothymidine (AZT) induced hepatotoxicity and genotoxicity along with change in expression of PARG and histone H3 acetylation. Toxicol Lett. 2008;177:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seth A, Sheth P, Elias BC, Rao R. Protein phosphatases 2A and 1 interact with occludin and negatively regulate the assembly of tight junctions in the CACO-2 cell monolayer. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11487–11498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li C, Krishnamurthy PC, Penmatsa H, et al. Spatiotemporal coupling of cAMP transporter to CFTR chloride channel function in the gut epithelia. Cell. 2007;131:940–951. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apak R, Güçlü K, Demirata B, et al. Comparative evaluation of various total antioxidant capacity assays applied to phenolic compounds with the CUPRAC assay. Molecules. 2007;19:1496–1547. doi: 10.3390/12071496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clayburgh DR, Barrett TA, Tang Y, et al. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase-dependent barrier dysfunction mediates T cell activation-induced diarrhea in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2702–2715. doi: 10.1172/JCI24970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham WV, Marchiando AM, Shen L, Turner JR. No static at all. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:314–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weflen AW, Alto NM, Hecht GA. Tight junctions and enteropathogenic E. coli. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz H, Fromm M, Bentzel CJ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) regulates the epithelial barrier in the human intestinal cell line HT-29/B6. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:137–146. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinugasa T, Sakaguchi T, Gu X, Reinecker HC. Claudins regulate the intestinal barrier in response to immune mediators. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Dandridge KS, Di A, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits cholera toxin-induced secretory diarrhea through CFTR-dependent protein interactions. J Exp Med. 2005;202:975–986. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiagarajah JR, Verkman AS. CFTR pharmacology and its role in intestinal fluid secretion. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:594–599. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell DW. Barrier function of epithelia. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:G275–G288. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1981.241.4.G275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madara JL, Barenberg D, Carlson S. Effects of cytochalasin D on occluding junctions of intestinal absorptive cells: further evidence that the cytoskeleton may influence paracellular permeability and junctional charge selectivity. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:2125–2136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.6.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura T, Higaki K. Gastrointestinal transit and drug absorption. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:149–164. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieto N, Lopez-Pedrosa JM, Mesa MD, et al. Chronic diarrhea impairs intestinal antioxidant defense system in rats at weaning. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2044–2050. doi: 10.1023/a:1005603019800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin AR, Villegas I, Sanchez-Hidalgo M, de la Lastra CA. The effects of resveratrol, a phytoalexin derived from red wines, on chronic inflammation induced in an experimentally induced colitis model. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:873–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Souza SM, Aquino LC, Milach AC, Jr, Bandeira MA, Nobre ME, Viana GS. Antiinflammatory and antiulcer properties of tannins from Myracrodruon urundeuva Allemao (Anacardiaceae) in rodents. Phytother Res. 2007;21:220–225. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]