Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a relatively new disease with ~10-fold increase in prevalence over the past 20 years,1,2 and has been found in ~6.5% of the population undergoing upper endoscopy.3 This disease has become one of the leading causes of dysphagia and food impaction in adults. For diagnosis, an endoscopy is performed where multiple biopsies are collected at random throughout the length of the esophagus, including the proximal and distal regions. On histopathology, the primary feature of EoE is infiltration of eosinophils into the mucosa. These mediators of inflammation may contribute to the development of structural abnormalities of the esophagus, including edema, rings, furrows, and strictures.4 Clinical symptoms do not improve with high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy, and the pH in distal esophagus is usually normal.5 However, the diagnostic criteria for this disease appear to lack clarity. EoE may be difficult to distinguish from GERD,6 which is also associated with increased eosinophilia but to a lesser extent, and the two diseases may be present at the same time. Eosinophils can also trigger allergic symptoms in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract.7

The degree of mucosal hypereosinophilia that defines EoE is controversial. While a diagnostic criteria of ≥15 eosinophils per high-power-field (hpf) on histology has been proposed,5 values as high as 30 eosinophils per hpf have been used, and no single number is widely accepted.8–10 Diagnostic uncertainty for this disease may be attributed in part to its patchy and focal nature. In addition, there is little known about the density or spatial distribution of eosinophils throughout the mucosa. Marked variability has been found within and between biopsy specimens of individual patients, resulting in a low sensitivity for detection. Currently, biopsy specimens are sectioned along a plane whose orientation to the mucosal surface is unknown. A non-uniform distribution of infiltrating eosinophils within the mucosa could result in a highly variable cell count that depends on the angle of sectioning, resulting in an inaccurate result. A novel method that can quickly and reliably quantify the number of cells over a 3-dimensional (3D) volume could be used to overcome this tissue processing limitation.

Human eosinophils contain granules that produce an intense autofluorescence in comparison to surrounding squamous epithelium.11–13 There is evidence to support flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as the source of this endogenous fluorescence.14 FAD is a coenzyme in the mitochondrial electron transport chain that has a maximum absorption at 445 nm, resulting in a peak fluorescence emission of 525 nm.15 Multi-photon microscopy (MPM) is a powerful method for collecting fluorescence images from cells and tissues,16 and has been used to perform in vivo imaging of FAD from squamous epithelium in animals.17,18 MPM imaging has inherent 3D resolution, uses near-infrared excitation for superior tissue penetration, has lower photobleaching effects, and is capable of providing quantitative information.19 We have previously demonstrated the use of MPM imaging as a highly accurate method for identifying and quantifying human eosinophils from mucosal smears of patients with allergic rhinitis.20 In this study, we aim to demonstrate the use of MPM to detect eosinophils within squamous epithelium, characterize the distribution of eosinophils with depth below the mucosal surface, and quantify the number of eosinophils within a 3D volume.

Methods

Study Subjects

Patients aged 18 to 65 years old who are undergoing routine endoscopy and have symptoms consistent with EoE, including dysphagia or food impaction were recruited prior to the procedure. Patients were excluded if they had a known bleeding disorder or an elevated INR (>1.5) due to anti-coagulantion. Patients with severe illness such as heart failure, difficulty breathing, or kidney failure were also excluded.

Specimen Collection/Preparation

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained for this study from the University of Michigan Medical School. Patients undergoing routine endoscopy were recruited, and written informed consent was obtained. Following completion of the routine portion of the endoscopy, additional specimens were collected for research purposes. A total of 4 biopsies were obtained: 2 from the proximal esophagus (~20 to 30 cm from the gums) and 2 from the distal esophagus (~2 cm above the Z-line). The specimens were placed immediately into separate vials containing normal saline, and transferred on ice to the laboratory microscope for imaging. The specimens were placed individually with the luminal side of the mucosa facing downward onto the surface of a #1.5 cover glass in a chamber slide. A small amount of normal saline was used to keep the specimens moist during imaging. Fluorescence images were collected from all specimens within 4 hours of resection.

After MPM imaging, the specimens were prepared for pathological evaluation. Specimens were placed in an Eppendorf tubes containing 5 ml of formalin and kept overnight for fixation. The following day, the specimens were immersed in 70% ethanol, cut in 5 μm sections, and stained with H&E for routine histopathology. The remaining portions of the specimens were paraffin embedded and stored.

Multi-Photon Microscopy

The specimens were first imaged on a laboratory multi-photon microscope (model# TCS SP5, Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) equipped with a tunable, ultra-fast laser that has a 100 femtosecond pulse width (Spectra-Physics, Mai Tai HP). MPM excitation at 700 nm was used based on the results of our previous study on cultured cells and human eosinophils,20 and fluorescence was collected between 500 and 600 nm. Both 2D and 3D images were obtained from each specimen. In order to achieve a large field-of-view (FOV) with deep tissue penetration, a 20× objective with a numerical aperture of 0.70 and working distance of 0.59 mm was used. Images were collected with a FOV of 775×775 μm2 and from 0 to 200 μm in axial depth. The settings for the laser and the detectors were kept constant for all specimens.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed to establish the source of the fluorescence. Frozen sections were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde/PBS, and then blocked with 20% FBS/PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with mouse anti-EPO primary antibody (clone AHE-1; Chemicon, Billerica, MA) in blocking solution (1:100 dilution) at 4°C overnight. This antibody reacts specifically with the human eosinophil peroxidase, an enzyme that plays an important role in endothelial injury in hypereosinophilic states.21 The specimens were then labeled with Alexa Fluor®-594 conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and mounted with ProLong® Gold anti-fade reagent (with DAPI; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Image Analysis

The MPM images were evaluated by using the “analyze and measure” command in Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Eosinophils were identified based on characteristics of fluorescent intensity, cell size, and cell shape. Cells that had dimensions ranging between 7 – 15 μm were included in the analysis.20 The mean and standard deviation of the fluorescence intensity of each cell and the surrounding squamous epithelium were measured. In addition, the size of each cell was recorded. Measurements were taken from 4 eosinophils and equivalent regions of epithelium in each specimen, if available. The maximum number of eosinophils per hpf were counted on the histology on viewing at 40× magnification. In addition, the absolute number of eosinophils on the MPM image were counted and compared with that found on histology. The 3D images were then generated using AutoQuantX2 (Media Cybernetics, Inc, Bethesda, MD) software. Vertical cross-sectional images were then obtained by taking a projection of the 3D image perpendicular to mucosal surface. An exponential fit of the average number of eosinophils versus mucosal depth was calculated using OriginPro 8.1 (OriginLab Corp. MA).

Pathology Review

The histology was reviewed by a gastrointestinal pathologist (HA) who was blinded to the results of the MPM images. The pathologist reported if eosinophils were present, and if so, quantified the maximum number of eosinophils per hpf.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance (p-value) was calculated using a two-sided Student's t-test with unequal variance. All results are shown as mean ± standard deviation. The relationship between eosinophil count on the MPM images and pathology evaluation was compared using linear regression. Statistics were calculated using the statistical package (data analysis) in Microsoft Excel 2007.

Results

Study Subjects

A total of n = 23 patients were recruited into this study with ages ranging from 21 to 64 years old (mean 42±13), including n = 12 female and n = 11 male. The patient demographics, symptoms on presentation, therapy prior to the study, and cell count on MPM and histopathology are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients included in study, presenting symptoms and therapy at time of endoscopy, and eosinophil cell count on multi-photon imaging (absolute over volume of 775×775×200 μm3) and pathology (maximum in hpf).

| Age | Gender | Presenting Symptoms | Therapy | Multi-Photon Absolute Eos# | Pathology Max Eos# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | F | dysphagia | Omeprazole 40 mg bid | distal-13 | distal-7 |

| 42 | M | h/o impaction, stricture, dilation | Omeprazole 20 mg prn | NA | NA |

| 36 | M | dysphagia, food impaction | Omeprazole 20 mg qd | NA | NA |

| 52 | F | EoE on Flovent, dilation q3-4 mo | none | distal-13 | distal-5 |

| 33 | M | dysphagia | Omeprazole 20 mg bid, Ranitidine 150 mg bid | 0 | 0 |

| 53 | F | GERD-like | Omeprazole 20 mg bid | 0 | 0 |

| 60 | M | h/o Barretts, suspected EoE | Omeprazole 20 mg qd | proximal-8 distal-12 | 0 |

| 56 | F | GERD-like | Ranitidine 150 mg prn | proximal-14 | 0 |

| 64 | F | GERD-like, family h/o EoE | none | 0 | 0 |

| 33 | F | new diagnosis of EoE | Omeprazole 20 mg bid | proximal-21 distal-20 | proximal-16 distal-5 |

| 34 | M | new diagnosis of EoE | Omeprazole 20 mg bid | proximal-7 distal-15 | proximal-4 distal-13 |

| 21 | M | dysphagia | none | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | M | h/o EoE, GERD-like, dysphagia | Omeprazole 20 mg bid | proximal-175 | 2 |

| 33 | M | h/o EoE | Pantoprazole 40 mg qd | proximal-5 | 0 |

| 24 | F | GERD-like | Omeprazole 20 mg qd | 0 | 0 |

| 43 | M | EoE, dysphagia | Omeprazole 40 mg qd | distal-56 | proximal-4 distal-29 |

| 26 | F | dysphagia | Lansoprazole 30 mg qd | proximal-4 distal-12 | 0 |

| 59 | F | dysphagia, GERD-like | Omepzole 40 mg qd | distal-11 | 0 |

| 49 | F | GERD-like | Omeprazole 20 mg bid | proximal-2 distal-5 | distal-1 |

| 41 | F | chest pain, GERD-like | Omeprazole 20 mg qd | distal-18 | distal-16 |

| 43 | M | dysphagia, food impaction | none | proximal-159 distal-31 | proximal-7 distal-66 |

| 57 | F | dysphagia | none | proximal-6 distal-110 | distal-4 |

| 42 | M | dysphagia | none | proximal-1 distal-10 | distal-2 |

Two-Photon Excited Fluorescence Imaging

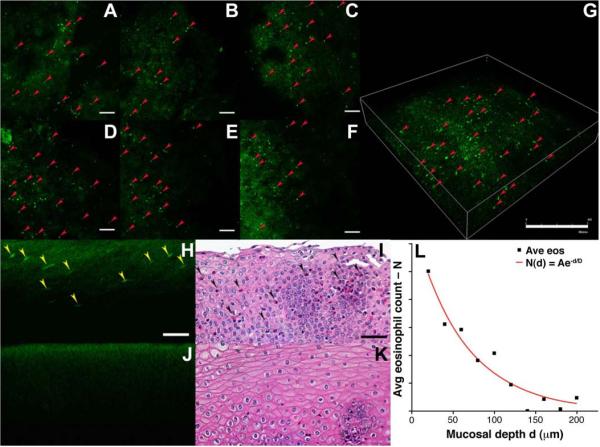

Based on routine histopathological review, eosinophils were found on n = 11 specimens. On MPM imaging, eosinophils were found on the same n = 11 specimens as well as on n = 5 additional specimens. In Fig. 1A–F, MPM images of esophageal mucosa collected in horizontal cross-sections (FOV 775×775 μm2) shows punctate regions of bright fluorescence from eosinophils (red arrows) infiltrating squamous epithelium, characterized by a diffuse and much dimmer pattern of fluorescence from the epithelium. Images are collected from the mucosal surface (d = 0 μm) and increase with depth in 20 μm increments, scale bar 100 μm. In Fig. 1G, the resulting 3D volume rendered image shows the distribution of eosinophils within the mucosa, scale bar 400 μm. We were able to accurately identify and quantify the eosinophils on these MPM images using fresh, unstained, unfixed specimen, and observed significantly greater mean MPM intensity from the eosinophils in comparison to the surrounding epithelium. The average target and background (T/B) ratio on the EoE positive images from a depth of d = 0 to 50 μm is 4.47±4.34 (range 1.38–31.14) and from d = 51 to 200 μm is 3.87±2.76 (range 1.94–15.59), p = 0.01. Vertical cross-sectional images (perpendicular to mucosal surface) show the distribution eosinophils with mucosal depth. These images are generated from the 3D volumetric images shown above. In Fig. 1H, several eosinophils (yellow arrows) can be identified from the punctate regions of increased fluorescence intensity compared to that of the surrounding squamous epithelium, scale bar 25 μm. The oval shape of the eosinophils result from processing performed to generate the vertical cross-sectional images. The corresponding histology (H&E) in Fig. 1I confirms the presence of eosinophils (black arrows). By comparison, a vertical cross-sectional image from a specimen of esophageal mucosa collected from a patient with no infiltrating eosinophils is shown in Fig. 1J as a control. The corresponding histology (H&E) shown in Fig. 1K confirms the absence of eosinophils.

Fig. 1. Detection of eosinophils on multi-photon imaging.

A–F) MPM images of esophageal mucosa collected in horizontal cross-sections (FOV 775×775 μm2) shows punctate regions of bright fluorescence from eosinophils (red arrows) infiltrating squamous epithelium. Images are collected from the mucosal surface (d = 0 μm) and increase with depth in 20 μm increments, scale bar 100 μm. G) 3D volume-rendered image shows the distribution of eosinophils within the mucosa, scale bar 400 μm. H) Vertical cross-sectional images show the distribution of eosinophils with depth. Several eosinophils (yellow arrows) can be identified, scale bar 25 μ I) Corresponding histology (H&E) from H) confirms the presence of eosinophils (black arrows). J) No infiltrating eosinophils are seen in control specimen. K) Corresponding histology (H&E) from J) confirms the absence of eosinophils. L) The average number of eosinophils at different depths below the mucosal surface shows that the cell concentration decreases in approximately an exponential fashion down to approximately 200 μm.

The average number of eosinophils on the positive specimens at different depths below the mucosal surface was found from the vertical cross-sectional images, and is shown in Fig. 1L. The concentration of eosinophils appears to be highest near the mucosal surface, and decreases in approximately an exponential fashion with tissue depth down to approximately 200 μm. A fit of the average number N of eosinophils as a function of depth d to the equation N(d) = Ae−d/D, resulted in values of A = 17 and D = 62.5 μm. We found that on the MPM images that 96% of the eosinophils present within the esophageal mucosa can be found within a 200 μm thick layer below the surface. A direct comparison of eosinophil count versus depth on histology was limited by artifacts introduced by specimen processing.

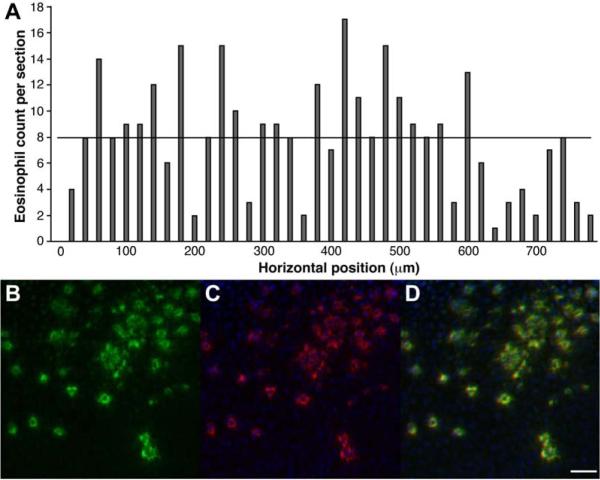

In Fig. 2A, the number of eosinophils found on individual vertical cross-sectional MPM images with dimensions 775 μm wide by 200 μm deep is shown in horizontal increments of 20 μm across the mucosal surface of the esophageal specimen. The numbers ranged from 1 to 17 cells with an average of 7.95±4.24 (horizontal black line). This result shows that any single section is unlikely to accurately represent the average number of cells over the volume of the specimen.

Fig. 2. – Variability and validation of eosinophils.

A) The number of eosinophils found on individual vertical cross-sectional MPM images is shown in horizontal increments across the mucosal surface of the esophageal specimen. The numbers range from 1 to 17 cells with an average of 7.95±4.24 (horizontal black line). B) On immunohistochemistry, numerous discrete foci of bright (green) fluorescence can be seen in a horizontal cross-sectional MPM image of superficial squamous epithelium. C) Serial section of the epithelium stained with the anti-EPO antibodies reveals numerous eosinophils (red). D) Registration of the MPM and immunohistochemistry images confirms eosinophils as source of bright fluorescence, scale bar 25 μm.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed to validate the source of the MPM signal. In Fig. 2B, numerous discrete foci of bright (green) fluorescence can be seen in a horizontal cross-sectional MPM image of superficial squamous epithelium. In Fig. 2C, a serial section of the epithelium stained with the anti-EPO primary and Alexa Fluor 594-labeled secondary antibodies reveals numerous eosinophils (red). The DAPI (blue) stain identifies cell nuclei. In Fig. 2D, registration of the MPM and immunohistochemistry images is reflected by an overlay, supporting the assertion that the MPM signal originates from eosinophils within the surface epithelium of the esophagus, scale bar 25 μm.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate the use of MPM imaging to identify and quantify eosinophils from esophageal mucosa. We found MPM to be sensitive to eosinophil autofluorescence from the mucosal surface down to a depth of about 200 μm. The T/B ratio was sufficiently high to distinguish eosinophils from the surrounding squamous epithelium over this depth. The average number of eosinophils on MPM was found to follow a decaying exponential distribution with a 1/e depth of 62.5 μm, suggesting that most of the infiltrating eosinophils are located within the squamous epithelium. In addition, eosinophils on MPM were found in all of the specimens confirmed as positive on pathology as well as in n = 5 additional specimens that the pathologist considered negative. Individual MPM sections provide a representative view of the number of cells seen on conventional histopathology, and were found to have considerable variability over the same dimensions that could lead to diagnostic error or data misinterpretation. Quantifying the number of eosinophils over an epithelial volume of rather than in a single section may achieve greater accuracy and measurement repeatability for EoE diagnosis. These results support a future study that correlates eosinophil counts on MPM with severity and resolution of clinical EoE disease using different therapies.

Currently, the diagnosis of EoE relies on a quantitative assessment of eosinophil cell count performed by a pathologist over a region of interest that is determined subjectively on tissue sections that are cut in an arbitrary orientation relative to the mucosal surface. In addition, the results reported are typically the maximum number seen rather than the absolute. Furthermore, clinical symptoms used to formulate this diagnosis can be non-specific and difficult to distinguish from GERD.22,23 Diagnostic accuracy and disease management can be greatly enhanced by establishing a standardized method for accurately measuring the number of eosinophils over a known tissue volume. The source of this intense MPM signal is believed to be FAD contained within eosinophil granules in high concentrations, distinguishing these cells from other mediators of inflammation, such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes.20 Once diagnosed and treated, patient follow-up can be performed in an objective and consistent manner. This technique can be particularly useful when symptoms persist by providing better quantification of eosinophils to determine optimal therapeutic response and to determine if future treatments will effectively reduce eosinophil count.

MPM imaging represents a novel approach for evaluating EoE by performing an “optical biopsy” of the specimen in a non-destructive and label-free manner. We found that 700 nm was an effective wavelength for two-photon excitation of the mucosal eosinophils based on our previous study.20 This result is consistent with the blue shift that has been observed in other studies, as well.24 In order to address the focal and patchy nature of this disease, miniature two-photon imaging instruments25–27 that are endoscope-compatible are being developed to collect MPM images in vivo. Conventional endoscopy alone has been found to be inadequate to support either diagnosis or treatment of EoE.28 Recently, an assessment of EoE has been demonstrated in vivo with confocal laser endomicroscopy.29 MPM imaging has potential to significantly improve tissue penetration depth and achieve 3D imaging with negligible risk of mutagenicity.30 MPM imaging is a novel and promising method for accurately detecting and quantifying eosinophils, and has potential to improve accuracy for disease detection and therapeutic monitoring.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (MICHR) grant #UL1RR024986, NIH U54 CA136429, and the University of Michigan Elma Benz Allergy Fellows Research Fund.

Obtained funding: Emily T. Wang

Technical support: Xiaoming Zhou

Study supervision: Emily T. Wang

Abbreviations

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FOV

field-of-view

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- hpf

high-power-field

- MPM

multi-photon microscopy

- T/B

target-to-background

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: All authors have nothing to disclose

Author Contributions: Study Concept and Design: Thomas D. Wang, Emily T. Wang

Acquisition of Data: Timothy Nostrant, Nastaran Safdarian, Zhongyao Liu

Analysis and Interpretation of Data: Nastaran Safdarian, Zhongyao Liu, Xiaoming Zhou, Henry Appelman, Thomas D. Wang, MD, PhD, Emily T. Wang

Drafting manuscript: Nastaran Safdarian, Zhongyao Liu, Thomas D. Wang, Emily T. Wang

References

- 1.Nonevski IT, Downs-Kelly E, Falk GW. Eosinophilic esophagitis: an increasingly recognized cause of dysphagia, food impaction, and refractory heartburn. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:623–6. 629–33. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.9.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potter JW, Saeian K, Staff D, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: an emerging problem with unique esophageal features. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:355–61. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veerappan GR, Perry JL, Duncan TJ, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in an adult population undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(4):420–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Grize L, et al. Natural history of primary eosinophilic esophagitis: a follow-up of 30 adult patients for up to 11.5 years. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1660–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. First International Gastrointestinal Eosinophil Research Symposium (FIGERS) Subcommittees. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, et al. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah A, Kagalwalla AF, Gonsalves N, et al. Histopathologic variability in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:716–21. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora AS, Yamazaki K. Eosinophilic esophagitis: asthma of the esophagus? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:523–30. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weil GJ, Chused TM. Eosinophil autofluorescence and its use in isolation and analysis of human eosinophils using flow microfluorometry. Blood. 1981;57:1099–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samoszuk MK, Espinoza FP. Deposition of autofluorescent eosinophil granules in pathologic bone marrow biopsies. Blood. 1987;70:597–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes D, Aggarwal S, Thomsen S, et al. A characterization of the fluorescent properties of circulating human eosinophils. Photochem Photobiol. 1993;58:297–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1993.tb09565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayeno AN, Hamann KJ, Gleich GJ. Granule-associated flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) is responsible for eosinophil autofluorescence. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;51:172–5. doi: 10.1002/jlb.51.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee HW, Choi HY, Han K, Hong JI. Selective fluorescent detection of flavin adenine dinucleotide in human eosinophils by using bis(Zn2+-dipicolylamine) complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4524–5. doi: 10.1021/ja070026r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denk W, Strickler JH, Webb WW. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science. 1990;248:73–76. doi: 10.1126/science.2321027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skala MC, Riching KM, Gendron-Fitzpatrick A, et al. In vivo multiphoton microscopy of NADH and FAD redox states, fluorescence lifetimes, and cellular morphology in precancerous epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19494–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708425104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skala MC, Squirrell JM, Vrotsos KM, et al. Multiphoton microscopy of endogenous fluorescence differentiates normal, precancerous, and cancerous squamous epithelial tissues. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1180–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmchen F, Denk W. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nat Methods. 2005;2:932–940. doi: 10.1038/nmeth818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Safdarian N, Liu Z, Wang TD, Wang ET. Identification of nasal eosinophils using two-photon excited fluorescence. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Protheroe C, Woodruff SA, de Petris G, et al. A novel histologic scoring system to evaluate mucosal biopsies from patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:749–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genevay M, Rubbia-Brandt L, Rougemont AL. Do eosinophil numbers differentiate eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(6):815–25. doi: 10.5858/134.6.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spechler SJ, Genta RM, Souza RF. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1301–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bestvater F, Spiess E, Stobrawa G, et al. Two-photon fluorescence absorption and emission spectra of dyes relevant for cell imaging. J Microsc. 2002;208(Pt 2):108–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2002.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engelbrecht CJ, Johnston RS, Seibel EJ, Helmchen F. Ultra-compact fiber-optic two-photon microscope for functional fluorescence imaging in vivo. Optics Express. 2008;16:5556–5564. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.005556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bao H, Allen J, Pattie R, Vance R, Gu M. Fast handheld two-photon fluorescence microenoscope with a 475 micron × 475 micron field of view for in vivo imaging. Opt Lett. 2008;33:1333–1335. doi: 10.1364/ol.33.001333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao Y, Nakamura H, Gordon RJ. Development of a versatile two-photon endoscope for biological imaging. Biomed Opt Express. 2010;1:1159–1172. doi: 10.1364/BOE.1.001159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peery AF, Cao H, Dominik R, et al. Variable reliability of endoscopic findings with white-light and narrow-band imaging for patients with suspected eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:475–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumann H, Vieth M, Atreya R, et al. First description of eosinophilic esophagitis using confocal laser endomicroscopy (with video) Endoscopy. 2011;43(S2):E66. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dela Cruz JM, McMullen JD, Williams RM, Zipfel WR. Feasibility of using multiphoton excited tissue autofluorescence for in vivo human histopathology. Biomed Opt Express. 2010;1:1320–1330. doi: 10.1364/BOE.1.001320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References (Online Only)

- 6.Parfitt JR, Gregor JC, Suskin NG, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: distinguishing features from gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study of 41 patients. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:90–6. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucendo AJ. Eosinophilic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(9):1013–21. doi: 10.3109/00365521003690251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]