Abstract

Aim

To determine the diagnostic efficacy of the size criteria for the detection of metastatic lymph nodes (LN) in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HCCA).

Introduction

LN metastasis is one of the most significant independent prognostic factors in patients with HCCA. Presently, in spite of the well known lack of sensitivity and specificity, one of the most used clinical criteria for nodal metastases is LN size.

Methods

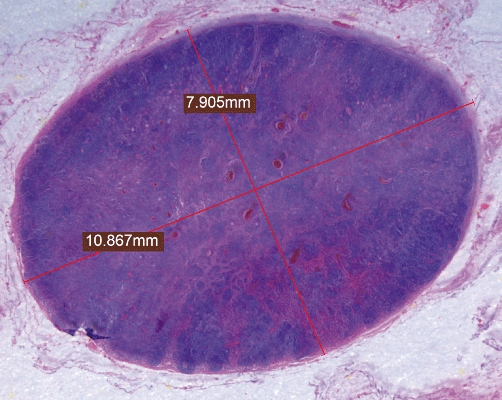

Pathological slides of 147 patients who had undergone exploration for HCCA were assessed. The size (maximum and short axis diameter) of each single node was retrieved from the pathology report or measured from a section on the glass slide using a stereo microscope and a calibrated ruler integrated in the software. When a metastatic lesion was detected, the proportion of the lesion in relation to LN size was estimated.

Results

Out of 147 patients, 645 LN were retrieved and measured. In all, 106 nodes (16%) showed evidence of metastasis. The proportion of positive nodes was 8% in nodes <5 mm and 37% in nodes >30 mm. Ten per cent of LN smaller than 10 mm were positive, whereas only 23% of LN larger than 10 mm were metastastically involved. No clear cut-off point could be found. Similar results were found for the short axis diameter. In 50% of positive LN, the metastatic lesion accounted for 10% or less of the LN size.

Conclusion

No cut-off point could be determined for accurately predicting nodal involvement. Therefore, imaging studies should not rely on LN size when assessing nodal involvement.

Keywords: cholangiocarcinoma < liver, radiological imaging/intervention < cholangiocarcinoma, pathology < cholangiocarcinoma, staging, lymph nodes

Introduction

The incidence of nodal involvement in resected specimens of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HCCA) has been reported to range from 30% to more than 50%.1–3 Lymph node (LN) metastasis is one of the most significant independent prognostic factors in patients with HCCA4–10. HCCA patients with nodal involvement beyond the hepatoduodenal ligament are currently considered unresectable.11,12 Hence, correct pre-operative and operative assessment of LN status is of crucial importance. Presently, in spite of the well known lack of sensitivity and specificity, one of the most used clinical criteria for nodal metastases is LN size. Moreover, the sizes of the maximum diameter or the short-axis diameter are commonly measured. Although enlarged regional LN on imaging studies are usually interpreted as metastases, there is no data which supports this interpretation. In addition, most patients with HCCA present with jaundice and in many cases with cholangitis. Consequently, LN size may also be increased as a result of local inflammation and infection, further impeding the correct assessment of nodal status.

A number of studies have addressed the accuracy of several imaging techniques, including ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET)13–16 for LN staging in HCCA. Unfortunately, these studies have a major drawback, because they correlate nodal positivity on a patient basis, rather than on a nodal basis. In other words, these studies correlate patients with a positive LN on imaging to patients with a positive LN during laparotomy. This carries two important limitations. First, it is difficult to determine whether the suspicious node on imaging corresponds to the positive node found during laparotomy. Second, there often is a delay between imaging and surgery, and LN size may alter during this delay and hamper accurate measurements of LN size by CT.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the association between LN size and the presence of metastasis in patients with HCCA measuring LN size using (low power) microscopical examination. The proportional size of the metastatic lesion within positive nodes was also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Patients

Histological slides of 147 patients who had undergone exploration for HCCA with at least one LN available were assessed. Laparotomies were performed from 1992 through to 2010. Patients who were found to be unresectable during laparotomy were also included, once at least one lymph node was histologically analysed. In all, 147 patients underwent exploration, of whom 100 patients underwent a resection. Out of the 47 unresectable patients, 160 LN were assessed, of which 54 (34%) were tumour positive. In these patients only suspicious (large) LN were assessed, as a complete lymphadenectomy was not useful, owing to unresectability. In 100 resected patients, 485 LN were retrieved, of which 52 (10.7%) were tumour positive. Patients and operation characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HCCA) patients who underwent a laparotomy from 1992 through to 2010

| Patients (n = 147) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patient details | ||

| Male | 94 | (64) |

| Female | 53 | (36) |

| Age (median) | 25–78 | (62) |

| Bismuth–Corlette classification | ||

| Type 1 or 2 | 38 | (26) |

| Type 3a | 57 | (38) |

| Type 3b | 32 | (22) |

| Type 4 | 20 | (14) |

| Resection performed | ||

| Yes | 100 | (68) |

| No | 47 | (32) |

| LN | ||

| Total | 645 | (100) |

| Negative LN | 539 | (84) |

| Positive LN | 106 | (16) |

| N0 patients | 93 | (63) |

| N1 patients | 54 | (37) |

| Average LN evaluated per patient | 4.4 | |

| Size in mm. (mean) | 11.3 | |

LN, lymph node.

Lymph nodes

In the first years of this study (until 2000), LN were not routinely harvested and only suspicious LN were removed and assessed. In the last decade a complete lymphadenectomy of the hepatoduodenal ligament was routinely performed, which was extended along the common hepatic artery until the celiac axis. Isolated LN were sent to the pathology department or dissected from the specimen by the pathologist according to a standardized protocol. Biopsies of LN were excluded, and only complete LN were assessed. The specimens were fixed in 5% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Grossly enlarged LN that could not be embedded in one single block were measured before processing and recorded in the pathology report. The size (maximum diameter and short-axis diameter) of each single node was retrieved from the report or measured from the pathological section on the glass slide. The separation of individual LN in clusters of para-aortic LN was difficult macroscopically, however, microscopically these LN could well be distinguished from each other. Images of the histological sections were acquired with a stereo microscope (model M165 FC; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a 1.0 × Planapo objective and a digital camera (model DFC 425C, Leica). The maximum diameter of the LN was measured offline using a calibrated ruler integrated in the software (Leica Application Suite) (Fig. 1). All LN were microscopically re-evaluated for the presence of metastasis; this analysis was carried out by an experienced hepatobiliary pathologist (F.Jt.K.). When a metastatic lesion was detected, the proportion of the metastatic lesion in relation to the LN was estimated and recorded.

Figure 1.

Pathological section of the lymph node (LN) on the glass slide. The maximum diameter and short axis diameter of the LN were measured off-line using a calibrated ruler integrated in the software

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 16.0.2.1; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data were compared using an independent sample t-test, and are expressed as means ± SD. Frequencies were analysed using the χ2 test. A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and were evaluated at the 5% level of significance.

Results

Correlation of LN metastasis and size?

Out of the 147 surgical specimens, 645 LN were retrieved and the axial size was measured. One hundred and six nodes (16%) showed evidence of metastasis. LN harbouring metastatic cancer cells were significantly larger when compared with negative LN (mean 14.85 ± 0.85 mm vs. 10.65 ± 0.31 mm, P < 0.001).

Determing a clinically useful cut-off point

The commonly used cut-off point in daily clinical practice for assessing nodal involvement is 10 mm. Out of 323 LN smaller than 10 mm, 32 (10%) showed metastatic involvement (Table 2). Out of 322 LN of 10 mm or larger, 74 (23%) were metastatically involved.

Table 2.

Lymph node (LN) classified according to size

| Negative lnn (%) | Positive lnn (%) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node size | |||||

| <10 mm | 291 | (90) | 32 | (10) | 323 |

| ≥10 mm | 248 | (77) | 74 | (23) | 322 |

| <5 mm | 150 | (92) | 13 | (8) | 163 |

| 5–9 mm | 177 | (88) | 24 | (12) | 201 |

| 10–19 mm | 159 | (76) | 50 | (24) | 209 |

| 20–29 mm | 36 | (80) | 9 | (20) | 45 |

| >30 mm | 17 | (63) | 10 | (37) | 27 |

| Total | 539 | (84) | 106 | (16) | 645 |

In order to further determine the chance of metastatic involvement based on size, we examined the frequency of metastatically involved LN in different size groups (i.e. 0–4 mm, 5–9 mm, 10–19 mm, 20–29 mm, >30 mm). As shown in Table 2, the proportion of metastically involved LN increased from 8% in the < 5 mm group to 37% in the >30 mm group (P < 0.001).

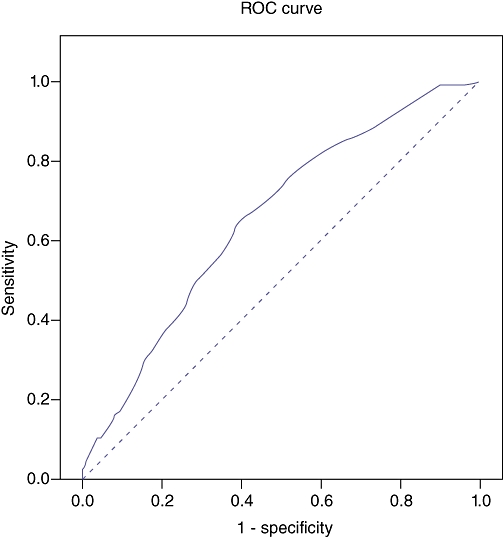

To determine the optimal cut-off point of the nodal size a ROC curve was constructed (Fig. 2). The area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curve was 0.658, with P < 0.001, testing whether the AUC > 0.50. As shown in Table 3, a cut-off of ≥12.5 mm in LN diameter could predict the presence of metastatic involvement with a sensitivity and specificity of 52% and 70%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC)-curve of lymph node (LN) size to determine LN metastasis in hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HCCA) [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.658; P < 0.001, testing whether the AUC > 0.50]

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of several cut-off values for predicting lymph node (LN) positivity according to size

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|

| Cut-off value | ||

| 4.5 mm | 93 | 19 |

| 9.5 mm | 70 | 54 |

| 10.5 mm | 65 | 61 |

| 12.5 mm | 52 | 70 |

| 14.5 mm | 42 | 75 |

| 16.5 mm | 32 | 83 |

Also the short-axis diameter was measured as shown in Table 4. The proportion of positive LN was 9% in LN with a short-axis diameter smaller than 6 mm, and increased to 28% in LN with a short-axis diameter bigger than 19 mm. Hence, the results of short-axis diameters are similar to maximum diameter results.

Table 4.

Lymph node (LN) classified according to size in short-axis diameter

| Negative lnn (%) | Positive lnn (%) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN size | |||||

| <10 mm | 416 | (87) | 64 | (13) | 480 |

| ≥10 mm | 123 | (75) | 42 | (26) | 165 |

| <6 mm | 270 | (91) | 27 | (9) | 297 |

| 6–9 mm | 146 | (80) | 37 | (20) | 183 |

| 10–19 mm | 103 | (75) | 34 | (25) | 137 |

| >19 mm | 20 | (71) | 8 | (29) | 28 |

| Total | 539 | (84) | 106 | (16) | 645 |

The proportion of metastatic cells within the LN

The proportion of malignant lesions in relation to the whole LN was estimated in all positive LN. As shown in Table 5, in half of the positive LN, the area of metastatic cells was 10% or less of the total LN. Hence, a needle biopsy of LN with 10% or less metastatic involvement could lead to a high incidence of false-negative results owing to a sampling error.

Table 5.

Metastatically involved lymph node (LN) and the proportion of involvement

| Percentage involvement | LN (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ≤5% | 29 | (27) |

| 10% | 24 | (22) |

| 15–45% | 23 | (20) |

| ≥50% | 30 | (28) |

| Total | 106 | |

The effect of LN size on the proportion of metastatic cells within the LN was evaluated (Table 6). Hypothetically, tumour growth would increase the size of metastically involved LN. Thus, LN with a larger diameter would harbour a larger proportion of metastatic cells. Yet, as shown in Table 6, LN size did not correlate with the proportion of metastatic cells within the LN (P = 0.31).

Table 6.

Metastatically involved lymph node (LN) and the proportion of involvement according to size

| 10% or less involvement of metastatic cells | >10% involvement of metastatic cells | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN size | |||||

| <5 mm | 6 | (46) | 7 | (54) | 13 |

| 5–9 mm | 9 | (37) | 15 | (63) | 24 |

| 10–19 mm | 25 | (50) | 25 | (50) | 50 |

| 20–29 mm | 7 | (78) | 2 | (22) | 9 |

| >30 mm | 6 | (60) | 4 | (40) | 10 |

| Total | 53 | (50) | 53 | (50) | 106 |

Discussion

The present study is the first to investigate directly the correlation between sizes of LN and the chance of metastatic infiltration in HCCA patients. We found that while metastatically involved LN of HCCA are significantly larger when compared with negative LN, the clinical usefulness of lymph node size is doubtful. Whereas only 23% of LN larger than 10 mm were involved with metastatic cells, 10% of LN smaller than 10 mm harboured metastatic cells. The highest chance of metastatic involvement was found in LN larger than 30 mm. However, this size category comprised no more than 4% of all nodes and the overall metastatic involvement in this group was only 37%. The relatively small AUC of the ROC curve of 0.66 also suggests that nodal size is not useful in predicting LN metastasis.

Noji et al. investigated the relationship of size and metastatic involvement in patients with biliary cancer based on CT criteria.17,18 The authors concluded that CT is not clinically useful for nodal staging in patients with biliary cancer owing to the lack of a correlation between LN size and metastatic infiltration. This is in accordance with our results, and we believe the present study also shows that any imaging modality will not be able to accurately predict metastatic infiltration based on nodal size alone. Other imaging criteria, such as nodal shape or signs of necrosis, could be more specific for metastatic infiltration. In addition, high-resolution MRI with superparamagnetic nanoparticles may be a promising method to identify LN metastasis19 in patients with HCCA.

The relationship between LN size and metastatic involvement has been investigated in various tumours, including uterine, breast, gastric, oesophageal and colorectal cancer.20–26 Similar results were found in these previous studies regarding the lack of clinical usefulness of LN size as predictor of metastatic involvement. The size of the LN found in the present study was large (mean 11.3 mm) in comparison to the LN in colorectal, uterine and gastric cancer (mean size 2.7 to 6.0 mm).20,21,23,24,27 This finding supports our assumption that perihilar LN in patients with HCCA are on average larger as a result of frequent, concomitant local inflammation and cholangitis. This also may have influenced the low correlation found between LN size and metastatic involvement in the present study.

The question remains whether the size after fixation and staining can be extrapolated to the size on imaging modalities. We have not performed imaging on resections specimens, which would ideally confirm the size relation between imaging size and measurement after fixation. Yet, Monig et al. did perform imaging on resections specimens, and thereby found a shrinkage factor of LN as a result of fixation and staining, which was calculated to be 10%.23 Taking into account a 10% shrinkage factor, 9% (25/255) of LN smaller than 10 mm were metastatically involved, whereas 22% (81/284) of LN of 10 mm or larger showed metastasis. Hence, results remain approximately the same when applying this shrinkage factor. We therefore believe that shrinkage as a result of fixation and staining was not a significant issue in the present study.

We also investigated the proportion of the metastatic lesion with regard to LN size. We found that half of the LN investigated, were 10% or less involved with metastatic cells. As a consequence, the chance of missing malignant cells in a metastatic LN using a needle biopsy is significant, which could be one of the factors leading to false negatives in these patients. Although the present study was not designed to assess this question, we believe that caution is warranted when performing a nodal biopsy. Nonetheless, the only study addressing this topic by Gleeson et al28 found metastases in LN of 8/47 (17%) patients with unresectable HCCA using endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) and missed only two patients with malignant perigastric LN.

A major drawback of the present study design was the unavailability of the ‘small’ LN of the unresectable patients, which where not removed owing to the unresectability. However, if we had chosen to exclude these patients, we would have introduced another major bias in the present study. We would then have excluded a group of patients with a large proportion of positive LN, thus resulting in a study group with a significantly lower proportion of positive LN, which is not representative of the clinical situation. When we analysed the LN sizes of only resectable patients, the relation of size and metastatic involvement is even worse, as shown in Table 7. Hence, we believe the above-mentioned bias will not affect our conclusions.

Table 7.

Lymph node (LN) classified according to size in resectable patients

| Negative lnn (%) | Positive lnn (%) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN size | |||||

| <10 mm | 237 | (15) | 15 | (6) | 252 |

| ≥10 mm | 196 | (84) | 37 | (16) | 233 |

| <5 mm | 123 | (95) | 6 | (5) | 129 |

| 5–9 mm | 140 | (92) | 12 | (8) | 152 |

| 10–19 mm | 126 | (83) | 25 | (17) | 151 |

| 20–29 mm | 30 | (88) | 4 | (12) | 34 |

| >30 mm | 14 | (74) | 5 | (26) | 19 |

| Total | 433 | (89) | 52 | (11) | 485 |

In conclusion, no clear cut-off point of LN size (maximum diameter, or short-axis diameter) in HCCA patients was found that could accurately predict nodal involvement. This finding has several implications. First, imaging studies should not rely only on LN size in predicting LN metastasis, and different imaging criteria should be used in addition to size criteria. And second, during a laparotomy, one cannot rely on nodal size alone when assessing nodal status. Furthermore, in 50% of the positive LN the metastatic lesion accounted for 10% or less of LN size. Consequently, the chance of missing malignant cells when performing a needle biopsy in positive LN should be considered.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Kitagawa Y, Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, Sano T, Yamamoto H, et al. Lymph node metastasis from hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 110 patients who underwent regional and paraaortic node dissection. Ann Surg. 2001;233:385–392. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200103000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463–473. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugiura Y, Nakamura S, Iida S, Hosoda Y, Ikeuchi S, Mori S, et al. Extensive resection of the bile ducts combined with liver resection for cancer of the main hepatic duct junction: a cooperative study of the Keio Bile Duct Cancer Study Group. Surgery. 1994;115:445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebata T, Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, Nagasaka T, Nimura Y. Hepatectomy with portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 52 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2003;238:720–727. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094437.68038.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito K, Ito H, Allen PJ, Gonen M, Klimstra D, D′Angelica MI, et al. Adequate lymph node assessment for extrahepatic bile duct adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2010;251:675–681. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3d2b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Ohta T, Kitagawa H, Tajima H, Miwa K. Role of nodal involvement and the periductal soft-tissue margin in middle and distal bile duct cancer. Ann Surg. 1999;229:76–83. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosuge T, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Makuuchi M. Improved surgical results for hilar cholangiocarcinoma with procedures including major hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 1999;230:663–671. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199911000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakeeb A, Tran KQ, Black MJ, Erickson BA, Ritch PS, Quebbeman EJ, et al. Improved survival in resected biliary malignancies. Surgery. 2002;132:555–563. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.127555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takao S, Shinchi H, Uchikura K, Kubo M, Aikou T. Liver metastases after curative resection in patients with distal bile duct cancer. Br J Surg. 1999;86:327–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Gulik TM, Kloek JJ, Ruys AT, Busch OR, van Tienhoven GJ, Lameris JS, et al. Multidisciplinary management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor): extended resection is associated with improved survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BJ, et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507–517. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruys AT, Busch OR, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Staging Laparoscopy for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: is it Still Worthwhile? Ann Surg Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1576-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hann LE, Greatrex KV, Bach AM, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Cholangiocarcinoma at the hepatic hilus: sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:985–989. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.4.9124155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SW, Kim HJ, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, et al. Clinical usefulness of 18F-FDG PET-CT for patients with gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:560–566. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masselli G, Gualdi G. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: MRI/MRCP in staging and treatment planning. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:444–451. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park HS, Lee JM, Choi JY, Lee MW, Kim HJ, Han JK, et al. Preoperative evaluation of bile duct cancer: MRI combined with MR cholangiopancreatography versus MDCT with direct cholangiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:396–405. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noji T, Kondo S, Hirano S, Tanaka E, Ambo Y, Kawarada Y, et al. CT evaluation of paraaortic lymph node metastasis in patients with biliary cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:739–743. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noji T, Kondo S, Hirano S, Tanaka E, Suzuki O, Shichinohe T. Computed tomography evaluation of regional lymph node metastases in patients with biliary cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:92–96. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, Deserno WM, Tabatabaei S, van de Kaa CH, et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2491–2499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tangjitgamol S, Manusirivithaya S, Jesadapatarakul S, Leelahakorn S, Thawaramara T. Lymph node size in uterine cancer: a revisit. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1880–1884. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez RO, Pereira DD, Proscurshim I, Gama-Rodrigues J, Rawet V, Sao Juliao GP, et al. Lymph node size in rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation–can we rely on radiologic nodal staging after chemoradiation? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1278–1284. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a0af4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noda N, Sasako M, Yamaguchi N, Nakanishi Y. Ignoring small lymph nodes can be a major cause of staging error in gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:831–834. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monig SP, Baldus SE, Zirbes TK, Schroder W, Lindemann DG, Dienes HP, et al. Lymph node size and metastatic infiltration in colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:579–581. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monig SP, Zirbes TK, Schroder W, Baldus SE, Lindemann DG, Dienes HP, et al. Staging of gastric cancer: correlation of lymph node size and metastatic infiltration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:365–367. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.2.10430138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotanagi H, Fukuoka T, Shibata Y, Yoshioka T, Aizawa O, Saito Y, et al. The size of regional lymph nodes does not correlate with the presence or absence of metastasis in lymph nodes in rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1993;54:252–254. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930540414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doi N, Aoyama N, Tokunaga M, Okamoto M, Hayashi M, Kameda Y, et al. Possibility of pre-operative diagnosis of lymph node metastasis based on morphology. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:977–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obwegeser R, Lorenz K, Hohlagschwandtner M, Czerwenka K, Schneider B, Kubista E. Axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer: is size related to metastatic involvement? World J Surg. 2000;24:546–550. doi: 10.1007/s002689910088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gleeson FC, Rajan E, Levy MJ, Clain JE, Topazian MD, Harewood GC, et al. EUS-guided FNA of regional lymph nodes in patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]