Abstract

Objectives

Diagnoses-specific sickness certification guidelines were recently introduced in Sweden. The aim of this study was to investigate to which extent general practitioners (GPs) used these guidelines and how useful they found them, 1 year after introduction.

Design

A cross-sectional questionnaire study. A comprehensive questionnaire about sickness certification practices in 2008 was sent to all physicians living and working in Sweden (n=36 898, response rate 60.6%). In all, 19.7% (n=4394) of the responders worked as GPs.

Setting

Primary healthcare in all Sweden.

Participants

The participating GPs who had consultations concerning sickness certification at least a few times a year (n=4278, 97%).

Main outcome measures

Descriptive statistics and prevalence ratios for the 11 questionnaire items about the use and usefulness of the sickness certification guidelines.

Results

A majority (76.2%) of the GPs reported that they used the guidelines. In addition, 65.4% and 43.5% of those GPs reported that the guidelines had facilitated their contacts with patients and social insurance officers, respectively. The guidelines also helped nearly one-third (31.5%) of the GPs to develop their competence and improve the quality of their management of sickness certification consultations (33.5%). About half experienced some problems when using the guidelines and 43.7% wanted better competence in using them. A larger proportion of non-specialists and of GPs with fewer sickness certification consultations had benefitted from the guidelines.

Conclusions

The national sickness certification guidelines implemented in Sweden were widely used by GPs already a year after introduction. Also, the GPs consider the guidelines useful in several respects, for example, in patient contacts and for competence development.

Article summary

Article focus

Sweden recently introduced national sickness certification guidelines. We investigated:

To what extent did the general practitioners use them 1 year later?

How useful did the general practitioners find them?

Key messages

Already after 1 year, most general practitioners used the guidelines and benefited extensively from them

Two-thirds of the general practitioners reported that the guidelines had facilitated their patient contacts and one-third that it facilitated their contacts with social insurance, other healthcare staff and employers

One-third stated that the guidelines had been helpful in competence development and improved the quality of their management of sickness certification cases

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths were the large study group and that all general practitioners in Sweden were included. Also, internationally this is the, so far, without comparison largest study of general practitioner's sickness certification practices. However, the non-response rate of 39% was a limitation, and we have no way of knowing if the non-responders differed with regard to use of the guidelines. However, only 11 of the 163 items in the questionnaire concerned the guidelines, why there is no reason to believe that no response was related to use of the guidelines.

Introduction

A systematic review of published studies showed that physicians experience sickness certification as problematic,1 and this was confirmed by later investigations,2–8 even to such an extent that it was considered a work environmental problem.9 Also, considering patients with the same complaints, there has been marked variation in whether sickness certificates have been issued and, if so, for how long; this applies especially to some of the vague diagnoses that are common in primary healthcare (PHC) and which underlie a large proportion of all sick-leave days.1 8 10

Clinical practice guidelines have been defined as ‘systematically developed statements to assist practitioners' and patients' decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances’.11 Such recommendations play an important role in enabling knowledge on best practice and evidence-based medicine to be implemented in routine practice. Improvements in quality of care and reduction of variation in practice are common reasons for establishing guidelines.12 This is exemplified by the comprehensive and detailed sickness certification guidelines that were introduced in the UK in 2002 and updated in 2010, developed by the Department for Work and Pensions to support medical practitioners in this context.13 Another type of sickness certification guidelines has been used for many years in the USA.14 Sickness certification cases are common among general practitioners (GPs), and the lack of scientific knowledge to base management of such cases is a large problem.1 The need for useful guidelines has been large, however, so has also the reluctance towards such guidelines been among GPs.1

In addition to the problems outlined in the first paragraph, were those related to the patients' right to equal treatment, to employers' and insurance officers' difficulties to assess the right to sickness benefits and to the previous dramatic increase in sick-leave rates. Involved stakeholders (healthcare, employers, social insurance, the Swedish Medical Association, the Swedish Society of Medicine and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, including the county councils responsible for healthcare) agreed on the need for sickness certification guidelines. In 2005, the Swedish government asked the National Board of Health and Welfare and the Social Insurance Agency to develop sickness certification guidelines. The efforts of these two agencies resulted in two sets of recommendations: overarching guidelines covering the principles related to sickness certification and diagnosis-specific guidelines for duration and degree (full or part time) of sick leave for a large number of diagnoses. Unfortunately, there was (and still is) only a very limited knowledge base regarding the need for, or consequences of being on, sick leave for a certain number of days among persons with different conditions and having different work tasks.15 16 Accordingly, the development of the guidelines could not be based on scientific evidence or even on particular studies. Instead, groups of clinicians with well-documented expertise in handling specific diagnoses were asked to give recommendations about the duration and degree of sickness absence for the most prevalent sick-leave diagnoses. Other systems for such guidelines were also scrutinised.13 14 The suggested guidelines were first tested by several GPs and were found to be useful. In October 2007, the guidelines were introduced in the whole country and were made available at the website of the National Board of Health and Welfare.17 Furthermore, the guidelines are continuously updated, for example, recommendations regarding a number of psychiatric disorders were added in May 2008.

Examples of issues in the overarching guidelines are the roles of physicians and social insurance officers; the importance of patients' participation in the discussion about sick leave; that the diagnosis-specific recommendations and special circumstances might be considered for the patient; to handle sickness certification as an active measure with a clear aim and that the patient, when possible, should keep in contact with the work site; and that it is not the disease in itself but the work incapacity resulting from the disease that can motivate sickness benefits. Furthermore, aspects of qulaity assurance are included.

Below, two examples from the diagnosis-specific guidelines are given. Regarding sickness certification with acute lumbago (ICD-10 code M54-55), it is stated that there is no scientific evidence that heavy work prolongs the rehabilitation or implies a risk for future disorders and complications. The work capacity might be reduced for up to 2 weeks if the patient has a physically strenuous work and otherwise for up to 1 week. Several recommendations are also given regarding actions to be taken if the sick leave exceeds these guidelines. Another example is acute appendicitis (ICD-10 code K35, K37); no need for a sickness certificate if the patient does not have a physically straining work (in Sweden, you can have self-certified sick leave for up to 7 days); if the patient has a physically strenuous work, up to 2 weeks sick leave is recommended after a laparoscopic operation and 3 weeks after a traditional operation, when possible for part time.

In Sweden, as in most countries, the physicians have the following tasks regarding consultations involving possible sickness certification: to determine whether the patient has a disease or injury and if it impairs the work capacity in relation to the patient's work demands; together with the patient discuss advantages and disadvantages of being sickness absent; to determine the grade and duration of sick leave; to make an action plan regarding measures needed during sick leave; to determine possible needs for other contacts within healthcare, with employers or other stakeholders and if so, establish such contacts; to issue a certificate that provides sufficient information for the employer or Social Insurance Office (SIO) for their decision about sickness benefits; to document assessments and actions taken. That is, the physician has two roles: as the treating physician of the patient and as a medical expert, providing information for other stakeholders.1 18 19

Our aim was to investigate to what extent GPs used the sickness certification guidelines and how useful they found them, a year after introduction.

Methods

Study design and participants

A comprehensive questionnaire including 163 questions about sickness certification practice was developed based on previous studies.3 9 16 20 The aim was to obtain more extensive and detailed knowledge on various aspects of how physicians manage sickness certification tasks in different types of clinics or practices. The study population comprised all 36 898 physicians living and working in Sweden in October 2008.19 They were identified in a register of all physicians in Sweden compiled by the company Cegedim AB, which also provided the following information on these professionals: year of examination and medical licensure, type of specialty, sex and age.

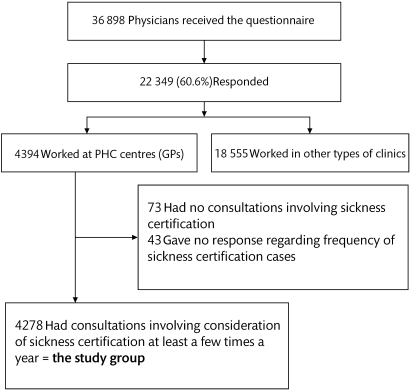

The questionnaire was administered by Statistics Sweden, and it was sent to the physicians' home addresses to avoid interaction with colleagues during completion. After three reminders, 22 349 (60.6%) of the physicians had responded (figure 1). Of those, 4394 (19.7%) reported that they worked chiefly in PHC, and here, those physicians are referred to as GPs. A majority of them were specialists in general practice (65.3%) or were in resident training to become such specialists (20.1%), whereas 3.0% had other specialties. In Sweden, GPs are qualified as specialists after 5 years of post-licensure specialist training. Inasmuch as no information was available about the total number of physicians working at PHC centres, the specific response rate for GPs could not be calculated. The response rate for all specialists in general practice was 59.9%; however, all of those do not work as GPs.

Figure 1.

Study population and study group. GPs, general practitioners; PHC, primary healthcare.

Our study group consisted of the 4278 GPs who had consultations concerning sickness certification at least a few times a year (figure 1). These physicians represented 97.4% of all GPs in the country. The results were stratified by sex, age group (24–44, 45–64 or >64 years), educational level (medical degree, registered physician, in resident training or specialist) and frequency of consultations involving sickness certification (more than five times a week, one to five times a week, less than once a week). Half of the GPs were women (49.9%) (table 1).

Table 1.

The GPs in the study group, stratified by sex, age and level of medical education

| GPs with consultations involving consideration of sickness certification at least a few times a year | Frequency of consultations involving consideration of sickness certification* |

Frequency of use of the new national guidelines†‡ |

|||||||

| >5 Times a week | 1–5 Times a week | Less than once a week | >5 Times a week | 1–5 Times a week | About once a month | A few times per year | Never or almost never | ||

| n=1819 | n=2234 | n=225 | n=142 | n=765 | n=1444 | n=831 | n=989 | ||

| n (%) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| All GPs | 4278 (100.0) | 42.5 (41.0 to 44.0) | 52.2 (50.7 to 53.7) | 5.3 (4.6 to 5.9) | 3.4 (2.9 to 4.0) | 18.3 (17.2 to 19.5) | 34.6 (33.2 to 36.1) | 19.9 (18.7 to 21.1) | 23.7 (22.4 to 25.0) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Women | 2135 (49.9) | 39.3 (37.2 to 41.4) | 55.0 (52.9 to 57.1) | 5.7 (4.7 to 6.7) | 3.7 (2.9 to 4.5) | 19.3 (17.6 to 21.0) | 36.6 (34.5 to 38.6) | 20.1 (18.4 to 21.8) | 20.3 (18.6 to 22.0) |

| Men | 2143 (50.1) | 45.7 (43.6 to 47.8) | 49.5 (47.3 to 51.6) | 4.8 (3.9 to 5.7) | 3.1 (2.4 to 3.8) | 17.4 (15.8 to 19.0) | 32.7 (30.7 to 34.7) | 19.7 (18.0 to 21.4) | 27.1 (25.2 to 29.0) |

| Age groups (years) | |||||||||

| 24–44 | 1607 (37.6) | 43.8 (41.4 to 46.2) | 52.3 (49.8 to 54.7) | 3.9 (3.0 to 4.9) | 4.8 (3.7 to 5.9) | 22.1 (20.0 to 24.1) | 35.5 (33.2 to 37.9) | 16.8 (15.0 to 18.7) | 20.7 (18.7 to 22.8) |

| 45–64 | 2491 (58.2) | 42.0 (40.1 to 44.0) | 52.5 (50.5 to 54.5) | 5.5 (4.6 to 6.4) | 2.6 (2.0 to 3.2) | 16.6 (15.2 to 18.1) | 34.9 (33.0 to 36.8) | 21.7 (20.0 to 23.3) | 24.2 (22.5 to 25.9) |

| 65–84 | 180 (4.2) | 37.8 (30.6 to 44.9) | 47.8 (40.4 to 55.1) | 14.4 (9.3 to 19.6) | 2.3 (0.0 to 4.5) | 8.6 (4.4 to 12.8) | 23.0 (16.7 to 29.3) | 23.0 (16.7 to 29.3) | 43.1 (35.7 to 50.5) |

| Educational level | |||||||||

| Specialist | 2964 (69.3) | 43.3 (41.5 to 45.1) | 51.6 (49.8 to 53.4) | 5.2 (4.4 to 6.0) | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.0) | 15.7 (14.4 to 17.1) | 34.9 (33.2 to 36.7) | 21.6 (20.1 to 23.1) | 25.3 (23.7 to 26.9) |

| In resident training | 843 (19.7) | 43.9 (40.5 to 47.2) | 50.46 (47.0 to 53.8) | 5.7 (4.1 to 7.3) | 5.8 (4.2 to 7.4) | 21.7 (18.9 to 24.5) | 35.6 (32.3 to 38.9) | 17.9 (15.2 to 20.5) | 19.0 (16.3 to 21.7) |

| Registered physician | 206 (4.8) | 49.5 (42.6 to 56.4) | 44.7 (37.8 to 51.5) | 5.8 (2.6 to 9.1) | 9.5 (5.4 to 13.7) | 22.6 (16.8 to 28.5) | 32.7 (26.1 to 39.2) | 11.1 (6.7 to 15.4) | 24.1 (18.1 to 30.1) |

| Medical degree | 265 (6.2) | 24.2 (19.0 to 29.3) | 71.3 (65.8 to 76.8) | 4.5 (2.0 to 7.0) | 1.6 (0.0 to 3.1) | 33.9 (28.0 to 39.7) | 29.6 (24.0 to 35.2) | 14.4 (10.1 to 18.7) | 20.6 (15.6 to 25.6) |

| Frequency of GPs' consultations involving sickness certification* | |||||||||

| >5 Times a week | 1819 (42.5) | – | – | – | 6.0 (4.9 to 7.1) | 20.7 (18.8 to 22.6) | 33.0 (30.8 to 35.1) | 15.7 (14.0 to 17.4) | 24.7 (22.7 to 26.7) |

| 1–5 Times a week | 2234 (52.5) | – | – | – | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.0) | 17.8 (16.2 to 19.4) | 36.1 (34.0 to 38.1) | 22.3 (20.5 to 24.0) | 22.4 (20.6 to 24.1) |

| <1 Time a week | 225 (5.3) | – | – | – | 1.0 (−0.4 to 2.3) | 4.3 (1.5 to 7.0) | 33.8 (27.4 to 40.3) | 31.4 (25.1 to 37.8) | 29.5 (23.3 to 35.7) |

Data represent proportions of GPs (per cent and 95% CI) regarding the frequency of their use of the guidelines and consultations involving consideration of sickness certification.

In all tables, the response options ‘>20 times a week’ and ‘6–20 times a week’ were combined to ‘>5 times a week’ and ‘about once a month’ and ‘a few times a year’ were combined to ‘less than once a week’.

The response options ‘>10 times a week’ and ‘6–10 times a week’ were combined to ‘>5 times a week’.

107 (2.5%) GPs did not respond.

GPs, general practitioners.

Variables

In this study, answers to the 11 questionnaire items about various aspects of the sickness certification guidelines were analysed. The questions and response options are given in the tables, and they concerned the following: how often the GPs used the guidelines (table 1), whether the guidelines had facilitated different types of contacts (table 2), the extent to which the guidelines had helped the GPs develop competence in managing sickness certification cases (table 3), how useful the GPs found the guidelines with regard to ensuring high-quality management of sickness certification cases (table 3), how problematic the GPs found it to adhere to the overarching guidelines and to issue sickness certificates in accordance with the diagnosis-specific guidelines (table 4), and the extent to which the GPs needed to develop their competence regarding the guidelines (table 5). The question “What difficulties, if any, do you experience in your contacts with the social insurance office (SIO)?” included the response option “Different interpretations of the new national sickness certification guidelines.”

Table 2.

Proportions of GPs who felt that the national guidelines had facilitated their contacts with different actors

| Do the new national guidelines for sickness certification facilitate your contacts with…* |

||||||||||||

| …patients?* |

…the SIO?† |

…the healthcare staff?‡ |

…the patients' workplaces or employment office?§ |

|||||||||

| n=1766 |

n=1163 |

n=789 |

n=805 |

|||||||||

| % | PR | 95% CI | % | PR | 95% CI | % | PR | 95% CI | % | PR | 95% CI | |

| All GPs | 65.4 | – | – | 43.5 | – | – | 29.4 | – | – | 30.2 | – | – |

| Educational level | ||||||||||||

| Specialist | 61.4 | 1 | – | 40.3 | 1 | – | 25.9 | 1 | – | 27.0 | 1 | – |

| In resident training | 70.8 | 1.15 | 1.03 to 1.29 | 46.9 | 1.17 | 1.01 to 1.34 | 34.0 | 1.31 | 1.11 to 1.56 | 34.8 | 1.29 | 1.09 to 1.52 |

| Registered physician | 70.6 | 1.15 | 0.92 to 1.44 | 46.5 | 1.15 | 0.87 to 1.53 | 43.8 | 1.69 | 1.26 to 2.27 | 34.5 | 1.28 | 0.92 to 1.77 |

| Medical degree | 87.3 | 1.42 | 1.20 to 1.69 | 65.1 | 1.62 | 1.32 to 1.98 | 43.5 | 1.68 | 1.32 to 2.15 | 46.7 | 1.73 | 1.37 to 2.20 |

| Frequency of GPs' consultations involving sickness certification | ||||||||||||

| >5 Times a week | 59.5 | 1 | – | 37.0 | 1 | – | 25.0 | 1 | – | 25.5 | 1 | – |

| 1–5 Times a week | 69.2 | 1.16 | 1.05 to 1.28 | 47.3 | 1.28 | 1.13 to 1.45 | 31.8 | 1.27 | 1.10 to 1.47 | 33.2 | 1.30 | 1.13 to 1.51 |

| <1 Time a week | 75.2 | 1.26 | 1.01 to 1.58 | 61.1 | 1.65 | 1.28 to 2.13 | 44.7 | 1.79 | 1.33 to 2.41 | 38.8 | 1.52 | 1.11 to 2.08 |

Data are presented as prevalence ratio (PR) with 95% CI.

No response from 101 (3%) GPs, and 380 (12%) GPs did not use the guidelines.

No response from 127 (4%) GPs, and 380 (12%) GPs did not use the guidelines.

No response from 120 (4%) GPs, and 380 (12%) GPs did not use the guidelines.

No response from 133 (4%) GPs, and 380 (12%) GPs did not use the guidelines.

GPs, general practitioners; SIO, social insurance office.

Table 3.

Proportions of GPs who considered that the national guidelines promoted development of their competence and improved their quality in managing sickness certification cases, respectively

| To what extent have the national guidelines helped you to develop your competence in managing sickness certification cases?* |

What effects have the diagnosis-specific sickness certification guidelines had on ensuring the quality of your management of sickness certification cases?† |

||||||||||

| To a large extent | To a fairly large extent | To some extent | Not at all | PR for a large or fairly large extent |

Very beneficial | Moderately beneficial | Not beneficial | PR for very beneficial |

|||

| n=185 | n=790 | n=1587 | n=531 | n=1039 | n=1799 | n=267 | |||||

| % | % | % | % | PR | 95% CI | % | % | % | PR | 95% CI | |

| All GPs | 6.0 | 25.5 | 51.3 | 17.2 | – | – | 33.5 | 57.9 | 8.6 | – | – |

| Educational level | |||||||||||

| Specialist | 5.0 | 23.5 | 52.8 | 18.7 | 1 | – | 28.6 | 61.3 | 10.1 | 1 | – |

| In resident training | 6.1 | 28.0 | 50.9 | 15.0 | 1.20 | 1.02 to 1.40 | 38.3 | 56.1 | 5.6 | 1.34 | 1.16 to 1.55 |

| Registered physician | 11.7 | 31.7 | 42.8 | 13.8 | 1.52 | 1.18 to 1.97 | 49.3 | 43.1 | 7.6 | 1.72 | 1.35 to 2.21 |

| Medical degree | 12.0 | 34.9 | 42.7 | 10.4 | 1.64 | 1.32 to 2.05 | 58.3 | 39.2 | 2.5 | 2.04 | 1.67 to 2.49 |

| Frequency of GPs' consultations involving sickness certification | |||||||||||

| >5 Times a week | 3.7 | 22.9 | 54.8 | 18.6 | 1 | – | 28.7 | 60.2 | 11.1 | 1 | – |

| 1–5 Times a week | 7.2 | 27.1 | 49.3 | 16.4 | 1.29 | 1.13 to 1.48 | 35.8 | 57.4 | 6.8 | 1.25 | 1.09 to 1.42 |

| <1 Time a week | 12.8 | 31.9 | 41.8 | 13.5 | 1.68 | 1.29 to 2.20 | 50.7 | 43.8 | 5.6 | 1.76 | 1.37 to 2.27 |

Data are presented as prevalence ratio (PR) with 95% CI.

No response from 89 GPs (2.8%).

No response from 77 GPs (2.4%).

GPs, general practitioners.

Table 4.

Proportions of GPs experiencing various degrees of problems using the overarching and the diagnosis-specific national sickness certification guidelines

| How problematic is it to apply the overarching national guidelines for sickness certification?* |

How problematic is it to issue sickness certificates in accordance with the national diagnosis-specific guidelines?† |

|||||||||||

| Very problematic | Fairly problematic | Somewhat problematic | Not at all problematic | PR for very and fairly problematic |

Very problematic | Fairly problematic | Somewhat problematic | Not at all problematic | PR for very and fairly problematic |

|||

| n=202 | n=965 | n=1233 | n=278 | n=252 | n=916 | n=1066 | n=234 | |||||

| % | % | % | % | PR | 95% CI | % | % | % | % | PR | 95% CI | |

| All | 7.5 | 36.0 | 46.0 | 10.4 | – | – | 10.2 | 37.1 | 43.2 | 9.5 | – | – |

| Educational level | ||||||||||||

| Specialist | 7.9 | 36.8 | 45.1 | 10.2 | 1 | – | 10.6 | 37.6 | 42.7 | 9.2 | 1 | – |

| In resident training | 7.9 | 36.8 | 45.7 | 9.6 | 1.00 | 0.87 to 1.16 | 11.1 | 38.3 | 42.5 | 8.1 | 1.03 | 0.89 to 1.18 |

| Registered physician | 6.6 | 38.0 | 43.8 | 11.6 | 1.00 | 0.76 to 1.31 | 8.8 | 38.9 | 42.5 | 9.7 | 0.99 | 0.75 to 1.31 |

| Medical degree | 3.0 | 23.7 | 59.2 | 14.2 | 0.60 | 0.44 to 0.80 | 4.0 | 26.2 | 52.3 | 17.4 | 0.63 | 0.46 to 0.85 |

| Frequency of GPs' consultations involving sickness certification | ||||||||||||

| >5 Times a week | 8.2 | 39.8 | 44.5 | 7.5 | 1 | – | 12.0 | 40.7 | 41.1 | 6.1 | 1 | – |

| 1–5 Times a week | 7.2 | 33.4 | 47.5 | 11.9 | 0.85 | 0.75 to 0.95 | 8.9 | 34.7 | 45.1 | 11.2 | 0.83 | 0.74 to 0.93 |

| <1 Time a week | 4.8 | 32.0 | 44.0 | 19.2 | 0.77 | 0.57 to 1.04 | 8.7 | 31.3 | 40.0 | 20.0 | 0.76 | 0.56 to 1.02 |

Data are presented as prevalence ratio (PR) with 95% CI.

No response from 54 GPs (1.7%), and 450 GPs had not used these guidelines.

No response from 66 GPs (2.1%), and 648 GPs had not used these guidelines.

GPs, general practitioners.

Table 5.

Proportions of GPs expressing a need for further competence in using the sickness certification guidelines

| To what extent do you need to further develop your competence in using the national guidelines?* |

||||||

| To a large extent | To a fairly large extent | To some extent | Not at all | PR for a large or fairly large extent |

||

| n=298 | n=1061 | n=1438 | n=310 | |||

| % | % | % | % | PR | 95% CI | |

| All GPs | 9.6 | 34.1 | 46.3 | 10.0 | – | – |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Specialist | 8.7 | 32.3 | 48.6 | 10.4 | 1 | – |

| In resident training | 12.3 | 39.8 | 40.4 | 7.5 | 1.27 | 1.12 to 1.44 |

| Registered physician | 12.9 | 33.3 | 45.6 | 8.7 | 1.13 | 0.88 to 1.44 |

| Medical degree | 8.0 | 36.0 | 41.0 | 15.0 | 1.07 | 0.86 to 1.34 |

| Frequency of GPs' consultations involving sickness certification | ||||||

| >5 Times a week | 9.5 | 33.0 | 47.0 | 10.5 | 1 | – |

| 1–5 Times a week | 9.5 | 35.1 | 45.9 | 9.5 | 1.05 | 0.94 to 1.17 |

| <1 Time a week | 12.0 | 33.8 | 43.7 | 10.6 | 1.08 | 0.83 to 1.39 |

Data are presented as prevalence ratio (PR) with 95% CIs.

No response from 75 GPs (2.4 %).

GPs, general practitioners.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used. Prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% CIs were estimated by modified Poisson regression and applied to assess the association between the different strata and the questions about the guidelines. Only the crude ratios are shown in the tables; tests for possible confounders such as age and sex showed no notable changes in the results, why only crude estimates are presented. SPSS software (V.18) was used in all the analyses.

Results

A majority of the GPs (76.2%, n=3182) reported that they used the national sickness certification guidelines at least a few times a year (table 1), and this group was subjected to further investigation regarding perceived usefulness of the guidelines. Slightly more than a fourth of these GPs (28.5%, n=907) used the guidelines at least once a week, and there were no gender differences. Younger GPs, GPs with only a medical degree and registered physicians used the guidelines more often than others.

A majority of those who used the guidelines reported that the recommendations were useful and had facilitated their contacts with patients (65.4%), as well as with the SIO (43.5%), other healthcare staff (29.4%) or with patients' workplace or employment office (30.2%) (table 2). Facilitation of such contacts was reported by a larger proportion of the GPs with only a medical degree and the GPs who had fewer consultations involving sickness certification (table 2). Eight per cent (n=249) had experienced difficulties in contacts with the SIO due to different interpretations of the guidelines (data not shown).

Close to one-third of the GPs (31.5%) stated that the guidelines had helped them to develop their competence in managing sickness certification cases to a large or fairly large extent (table 3). Moreover, for a third (33.5%), the diagnosis-specific guidelines had improved the quality of their management of sickness certification cases (table 3). A larger proportion of non-specialists and GPs with fewer sickness certification consultations reported that the guidelines had helped them to develop competence and quality.

Nearly half of the GPs found it fairly or very problematic to use both the overarching guidelines and the diagnosis-specific guidelines (43.5% and 47.3%, respectively; table 4). A significantly lower rate of those with only a medical degree found this problematic. Ten per cent stated that they had no need to further develop their competence in using the guidelines, whereas 9.6% felt that they had an extensive need in that area. The rest (80.4%) wanted to increase their competence to some degree, especially among those in residence training (PR=1.27) (table 5).

Discussion

In summary, 76.3% of the GPs used the national sickness certification guidelines 1 year after these recommendations were launched. Up to 65.4% reported that the guidelines had facilitated their contacts with their patients and >40% stated the same regarding their contacts with the SIO. Nearly one-third stated that the guidelines had helped them develop their competence and had also greatly improved the quality of their management of sickness certification cases. A higher rate of both non-specialists and GPs with fewer sickness certification consultations had benefited more extensively from the guidelines. Most of the physicians (90%) indicated that they had at least some degree of need to develop their competence in applying the guidelines.

In general, even long after guidelines are introduced, many of them are not used by the targeted physicians.21 22 Indeed, investigations have shown considerable variation in the application of guidelines, and this has been demonstrated using different outcome measures. In one study,13 self-reporting by GPs indicated that there was low awareness (36%) and even lower use (20%) of the sickness certification guidelines in the UK a number of years after they were introduced. Another questionnaire investigation demonstrated that 34% of GPs were aware of the existence of the UK guidelines concerning return to work after surgery, 3 years after these recommendations were introduced.23 In yet another such study in the UK,24 50% of physicians reported that they used 26 guidelines for gastrointestinal disorders and endoscopy but the response rate was only 4.1%. In Norway, an assessment of self-reported use of 19 recently introduced guidelines for common problems in general practice showed that 52% used the guidelines for management of diabetes, whereas 3%–31% used the rest of the guidelines.25 Other studies have measured the extent to which clinical decisions actually comply with guidelines. For example, an average of 67% of physicians in the Netherlands based their decisions on clinical guidelines for family medicine,21 and there was partial or complete compliance with guidelines for venous thromboembolism in 84% of the patients in an investigation conducted in the USA.26

Compared with the results of these studies, the proportion of GPs in Sweden who were using the new guidelines already 1 year after introduction is large. That is probably related partly to the need for such guidelines that was expressed among physicians,19 partly to the nationwide launch of these recommendations and partly to the support of them from different stakeholders, including the medical associations. It has been shown that many young physicians are concerned about their lack of knowledge in sickness certification,27 and hence use of the guidelines is probably a way of developing such proficiency. However, others13 have observed extensive use of sickness certification guidelines among GPs with higher qualifications, as have we. The communication between the GPs and their patients has an important role in sickness certification, especially in cases involving doctor–patient conflicts.1 18 28 Furthermore, problems in the contact between the GPs and the SIOs have been reported,29 and SIOs have stressed the significance of mutual understanding in that context.30 Our results indicate that the new guidelines have already led to improvements of this.

In general, there were only limited differences between GPs of different educational levels and with different frequency of consultations involving sickness certification, respectively, regarding problems in applying the guidelines and need for further competence in using them. Physicians with only a medical degree were the only ones who reported fewer problems in using the guidelines compared with the other groups, possibly because they had not yet developed their own routines in this field (tables 4 and 5).31 32

Strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study were the large study group and the fact that all GPs in Sweden were included. This is, so far, without comparison the largest study of GP's sickness certification practices in general and especially of GP's use of sickness certification guidelines. However, the non-response rate of 39% was a limitation, and we have no way of knowing if the non-responders differed with regard to use of the guidelines. However, the questionnaire did not focus only on the guidelines; only 11 of the 163 questions concerned the guidelines, why there is no reason to believe that the response rate was related to use of the guidelines. Moreover, the response rate was higher than in most comparable studies.33 34 In all questionnaire studies, self-reporting can entail a risk for bias. In general, GPs will probably under-report using guidelines, if they interpret ‘use of guidelines’ to mean visiting a particular website instead of complying with the recommendations, as was found in an interview study (published in Swedish as a master thesis).

Conclusions and implications

The national guidelines for sickness certification that were introduced in Sweden were already a year later widely used by GPs. These physicians found the guidelines useful in several respects, such as enhancing contacts with patients and with SIOs, as well as raising their competence in sickness certification. The sickness certification guidelines are subject to continuous development and evaluation, and it is important that this be done from different perspectives, such as patient safety, education of physicians-in-training and enhancement of contacts between physicians and other stakeholders. These guidelines might be even more accessible if they are integrated with the new electronic sickness certificate about to be implemented in Sweden. In general, the guidelines have fulfilled positive expectations put on them. Results from studies on GPs sickness certification practices in different countries are surprisingly alike which might mean that equivalent guidelines might be found useful also in other countries.1 8

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Skånér Y, Nilsson GH, Arrelöv B, et al. Use and usefulness of guidelines for sickness certification: results from a national survey of all general practitioners in Sweden. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000303. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000303

Funding: Funding sources were the Swedish Research Council of Working Life and Social Sciences, the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, AFA Insurance and the National Social Insurance Agency. The sponsors were in no way involved in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, interpretation of the data or in the writing and submitting of the article. All researchers have had access to all data.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm (Reg. No. 2008/795-31).

Contributors: All authors participated in the study design. EH performed the data management and statistical analyses. YS drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in interpretation of data and reviewed the manuscript. KA, GHN, BA and CL initiated the project and developed the questionnaire, and KA is the guarantor.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Wahlström R, Alexanderson K. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 11. Physicians' sick-listing practices. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2004;63:222–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussey S, Hoddinott P, Wilson P, et al. Sickness certification system in the United Kingdom: qualitative study of views of general practitioners in Scotland. BMJ 2004;328:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Löfgren A, Arrelöv B, Hagberg J, et al. Frequency and nature of problems associated with sickness certification tasks: a cross sectional questionnaire study of 5455 physicians. Scand J Prim Health Care 2007;25:178–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Knorring M, Sundberg L, Löfgren A, et al. Problems in sickness certification of patients: a qualitative study on views of 26 physicians in Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:22–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engblom M, Alexanderson K, Rudebeck CE. Characteristics of sick-listing cases that physicians consider problematic—analyses of written case reports. Scand J Prim Health Care 2009;27:250–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerner U, Alexanderson K. Issuing sickness certificates: a delicate task for physicians. Scand J Public Health 2009;37:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiscock J, Byrne P, Peters S, et al. Complexity in simple tasks: a qualitative analysis of GPs? Completion of long-term incapacity forms. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2009;10:254–69 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynne-Jones G, Mallen CD, Main CJ, et al. What do GPs feel about sickness certification? A systematic search and narrative review. Scand J Prim Health Care 2010;28:67–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swartling MS, Hagberg J, Alexanderson K, et al. Sick-listing as a psychosocial work problem: a survey of 3997 Swedish physicians. J Occup Rehabil 2007;17:398–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waddell G, Burton K. Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-Being? London: TSO, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field MJ, Lohr KN, eds. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, et al. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999;318:527–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roope R, Parker G, Turner S. General practitioners' use of sickness certificates. Occup Med (Lond) 2009;59:580–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed P, ed. The Medical Disability Advisor. Workplace Guidelines for Disability Duration. Singapore: Reed Group Holdings, Ltd., 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vingård E, Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Consequences of being on sick leave. Scand J Public Health 2004;32(Suppl 63):207–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Swedish council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 12. Future need for research. Scand J Public Health 2004;32(Suppl 63):256–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anonymous. Försäkringsmedicinskt Beslutsstöd [Sickness Certification Guidelines] (In Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Socialstyrelsen [National Board of Health and Welfare] 2011. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/riktlinjer/forsakringsmedicinsktbeslutsstod [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen DA, Aylward M, Rollnick S. Inside the fitness for work consultation: a qualitative study. Occup Med (Lond) 2009;59:347–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindholm C, Arrelov B, Nilsson G, et al. Sickness-certification practice in different clinical settings; a survey of all physicians in a country. BMC Public Health 2010;10:752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrelöv B, Alexanderson K, Hagberg J, et al. Dealing with sickness certification—a survey of problems and strategies among general practitioners and orthopaedic surgeons. BMC Public Health 2007;7:273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):II46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hetlevik I, Holmen J, Krüger O, et al. Fifteen years with clinical guidelines in the treatment of hypertension—still discrepancies between intentions and practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 1996;15:134–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clayton M, Verow P. Advice given to patients about return to work and driving following surgery. Occup Med (Lond) 2007;57:488–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefanidis D, Richardson WS, Fanelli RD. What is the utilization of the SAGES guidelines by its members? Surg Endosc 2010;24:3210–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treweek S, Flottorp S, Fretheim A, et al. [Guidelines in general practice—are they read and are they used?] (In Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2005;125:300–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shackford SR, Rogers FB, Terrien CM, et al. 10-year analysis of venous thromboembolism on the surgical service: the effect of practice guidelines for prophylaxis. Surgery 2008;144:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walters G, Blakey K, Dobson C. Junior doctors need training in sickness certification. Occup Med (Lond) 2010;60:152–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swartling MS, Alexanderson KA, Wahlström RA. Barriers to good sickness certification—an interview study with Swedish general practitioners. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:408–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Timpka T, Hensing G, Alexanderson K. Dilemmas in sickness certification among Swedish Physicians. Eur J Public Health 1995;5:215–19 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorstensson CA, Mathiasson J, Arvidsson B, et al. Cooperation between gatekeepers in sickness insurance—the perspective of social insurance officers. A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabbay J, le May A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed “mindlines?” Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. BMJ 2004;329:1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell A, Ogden J. Why do doctors issue sick notes? An experimental questionnaire study in primary care. Fam Pract 2006;23:125–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pransky G, Katz J, Benjamin K, et al. Improving the physician role in evaluating work ability and managing disability: a survey of primary care practitioners. Disabil Rehabil 2002;24:867–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.