Bradby’s (2010) critique of our paper ‘Race and Shared Decision-Making: Perspectives of African-Americans with Diabetes’ (Peek at al., 2010) highlights important questions about racism, patient/provider communication and U.S. health disparities. We address her concerns through the following questions: 1) How can we best conceptualize racism in healthcare? 2) Is there evidence for racism in the current U.S. healthcare system?, 3) How can we disentangle racial discrimination from discrimination based on other social factors?, 4) Is there evidence and/or theoretical model(s) that link institutional racism to population-level health disparities?, 5) Is there evidence and/or theoretical model(s) that link the patient/provider relationship and communication disparities to population-level health disparities?, and 6) Are there potentially effective solutions to address institutional racism, particularly unconscious provider bias?

How can we best conceptualize racism in healthcare?

The Institute of Medicine (IOM), in its landmark report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, identified two causes of healthcare disparities: healthcare systems and discrimination at the patient/provider level (defined as ‘biases, prejudices, stereotyping, and uncertainty in clinical communication and decision-making’) (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2002, p.4).

Within this context, one can consider theoretical models to further define racism and discrimination within healthcare. We used Camara Jones’ framework because of its widespread use and because it was developed to highlight how racism can lead to health disparities (Jones, 2000). Jones describes three levels of racism: institutionalized racism, personally-mediated racism and internalized racism. Institutionalized racism, defined as differential access to goods, services, and opportunities by race, includes differential access to health insurance, which study participants described as a contributing factor to communication disparities between African-Americans and their physicians. It is important to note that institutional racism does not require personal bias commonly associated with term ‘racism.’ This type of racism, termed personally-mediated racism, is defined as prejudice (differential assumptions about the abilities, motives, and intentions of others according to their race) and discrimination (differential actions toward others according to their race) (Jones, 2000). Prejudice and discrimination may manifest as disrespect, poor service and failure to communicate options (Jones 2000), all of which our study participants described in their experiences within the U.S. healthcare system. They attributed differential physician assumptions (e.g. “maybe they assumed that she would not understand”) and behaviors (e.g. “they just talk right at the patient because they are black”) specifically to being African-American, indicating participants’ perceived influence of race on patient/physician encounters.

There are two important points to underscore about personally mediated racism. First, it may occur subconsciously. Well-meaning individuals may harbor assumptions about people that reflect societal norms. According to social science theory, everyone uses the strategy of social categorization (e.g. by race or gender) in an attempt to understand, predict and control one’s environment and process new information (Hamilton, 1981; Klopf, 1991). Unfortunately, this process can lead to exaggeration of negative inter-group differences (stereotypes) and an over-generalization of them (bias/prejudice) (Klopf, 1991; Lalonde, & Gardner, 1989). Second, although discrimination may be subconscious, its impact is powerful. Racism need not take overt forms of slavery or segregation to have a significant effect. In fact, the most potent forms of discrimination that African-Americans currently experience are subtle forms experienced chronically (Banks, Kohn-Wood, & Spencer, 2006).

Finally, Jones defines internalized racism as the acceptance by members of stigmatized races of negative messages about their abilities and intrinsic worth (Jones, 2000). Internalized racism can have many manifestations, including helplessness, self-devaluation, and limiting one’s right to self-determination and self-expression (Jones, 2000). Our participants reported a decreased ability of African-Americans to question their treatment and speak up to their physicians, and also described devaluing characteristics (e.g. poor physical presentation, not “speaking well”) as potential causes of communication disparities.

The above literature defining racism in healthcare provides a strong theoretical framework for understanding its contribution to health disparities, and corroborates the findings of our study.

Is there evidence for racism in the current U.S. healthcare system?

Indeed, there is evidence that racism exists within the U.S. healthcare system (institutional racism) and among healthcare providers (personally-mediated racism). The IOM report Unequal Treatment reviewed the disparities literature and concluded that an important contributor to racial disparities in health status is the difference in the quality of medical care given to racial/ethnic minorities (Smedley et al., 2002). For example, among diabetes patients, African-Americans are less likely to receive influenza vaccinations, have glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) testing or cholesterol testing (Peek, Cargill, & Huang, 2007).

Healthcare providers may harbor racial biases (personally mediated racism), and may be at increased risk of using stereotypes as cognitive short-cuts because of clinical encounter characteristics (time pressure, high cognitive demand, limited resources and uncertainty) (Hamilton, 1981). There is evidence that physicians hold stereotypes based on patient characteristics (e.g. race), which may influence their interpretation of patient behaviors and symptoms, and consequently their clinical decisions (Finucane & Carrese, 1990; Burgess, van Ryn, Dovidio, & Saha, 2007). For example, one study found that physicians were more likely, after controlling for confounding variables, to rate their African-American patients as less educated, less intelligent, more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol, and less likely to adhere to treatment regimens (van Ryn & Burke, 2000). Green, Carney, Pallin, Ngo, Raymond, Iezzoni, & Banaji (2007) documented the association between implicit physician bias and racial disparities in treatment recommendations for acute myocardial infarctions.

While there is no consensus on how to best measure healthcare discrimination (Kressin, Raymond, & Manze, 2008), most researchers rely upon patient reports of perceived discrimination--a strategy with inherent advantages and disadvantages. While perceptions may be misinterpreted, they do reflect patients’ personal experiences and how they are internalized, which may be important to how discrimination affects health (see discussion below). This may be particularly true for patients who lived through U.S. segregation, as their historical healthcare experiences undoubtedly shaped how they currently experience healthcare encounters. In our study, all but three participants were born before the 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawing U.S. segregation.

There is growing evidence that minorities perceive healthcare discrimination and that such perceptions are associated with important outcomes, such as less preventive healthcare (e.g. cancer screening, dyslipidemia screening, and influenza vaccinations) (Hausmann, Jeong, Bost, & Ibrahim, 2008; Trivedi & Ayanian, 2006), prescription medication utilization and medical testing/treatment (Van Houtven, Voils, Oddone, Weinfurt, Friedman, Schulman, et al., 2005). Among diabetes patients, perceived healthcare discrimination is associated with lower quality physician interactions, and worse diabetes care and outcomes (Piette, Bibbins-Domingo, & Schillinger, 2006; Ryan, Gee, & Griffith, 2008; Trivedi & Ayanian, 2006).

The above evidence compels us to conclude that racism is embedded within the U.S. healthcare system, at both institutional and personally mediated levels.

How do we disentangle racial discrimination from discrimination based on other social factors?

Racial disparities in healthcare (institutional racism) persist after adjusting for other sociodemographic variables such as gender and class (Smedley et al., 2002). There has been less research separating personally-mediated racism from other forms of discrimination. However, in several studies, healthcare discrimination attributed to race (vs. other social factors) was reported most commonly among minorities and associated with worse care and outcomes (Trivedi & Ayanian, 2006; Ryan et al., 2008; Ren, Amick, & Williams, 1999). For example, in a study of discrimination and diabetes management, perceived racial discrimination was associated with a 50% lower probability of three aspects of diabetes care, while perceived gender discrimination was associated with a 22% lower probability of one aspect of care (Ryan et al., 2008).

In our study, we explored the relationship between race and shared decision-making (SDM), while recognizing that other social factors affect such communication and may interact with race. As we note in our paper, an important next step will be to explore how perceptions of race interact with other social variables to influence SDM.

Is there evidence/theoretical model(s) that link institutional racism to population-level health disparities?

Several well-known models broaden our understanding of how institutional racism may lead to population-level health disparities. The chronic stress induced by personal experiences with discrimination is one mechanism by which institutional racism may affect health (Williams, 1996; Jones, 2000). For example, McEwen’s model (1998) of allostatic load emphasizes interactions between cognitive processes (i.e. responses to perceived stress) and physiological responses (e.g. cardiovascular, immunological effects) to explain how environmental stressors, major life events and trauma (e.g. racism) result in physiological changes. In Massey’s biosocial model of racial stratification (2004), concentrations of poverty and violence (due to socioeconomic inequalities and residential segregation) result in high allostatic loads that have downstream health effects such as coronary artery disease, inflammatory disorders and cognitive impairment. Among African-Americans, perceptions of discrimination are independently associated with C-reactive protein, a marker of systemic inflammation that correlates to cardiovascular disease and other health outcomes andprecursors to cardiovascular disease (e.g. coronary artery calcification) (Lewis, Everson-Rose, Powell, Matthews, Brown, Karavolos et al., 2006; Lewis, Aiello, Leurgans, Kelly, & Barnes, 2009). Institutional racism may also affect health through negative health behaviors such as delays in healthcare utilization and treatment non-adherence (Casagrande, Gary, LaVeist, Gaskin, & Cooper, 2007), and cigarette and alcohol use (Borrell, Jacobs, Williams, Pletcher, Houston, & Kiefe, 2007). Institutional racism, as perceived discrimination within society, is associated with poor health measures, including depression, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disease (Gee, Spencer, Chen, & Takeuchi, 2007; Williams et al., 1997).

In the above, we have highlighted some of the evidence linking institutional racism to health outcomes, and illustrated models proposing pathways between racism and population-level health disparities.

Is there evidence and/or theoretical model(s) that link the patient/provider relationship and communication disparities to population-level health disparities?

Evidence-based models have shown how health providers may contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health (van Ryn, 2002; Ashton, Haidet, Paterniti, Collins, Gordon, O’Malley, et al., 2003). These models focus on patient/provider relationships and how bias, health and interpersonal behaviors, cognitive and affective factors, perceptions, and professional decision-making influence healthcare delivery and health outcomes.

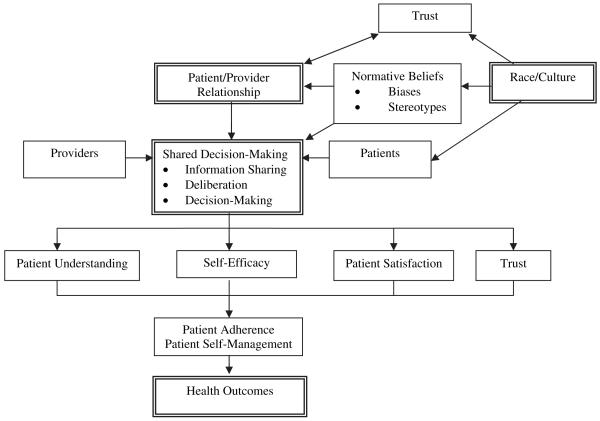

Based on our research, we have developed a conceptual model for exploring relationships between race, shared decision-making and health outcome. It is important to note that our model is nested within the broader context of the healthcare system and macro-level factors which also affect health outcomes and health disparities.

The model demonstrates how shared decision-making is a joint endeavor, and its successful execution depends on the preference of both patients and providers to engage in this process, and on the patient/provider relationship, which creates the situational context for SDM. Race may potentially affect SDM through several mechanisms. First, racial differences may exist in patient preferences for SDM or in how SDM is conceptualized. A study of a multi-ethnic population found no differences between white and African-American patients in preferences for SDM (Peek, Tang, Cargill, & Chin, 2007), suggesting that patient preference is unlikely to drive SDM disparities. In a prior analysis, we found that African-Americans with diabetes defined SDM in ways that are different than how it is conceptualized in the literature (Peek, Quinn, Gorawara-Bhat, Odoms-Young, Wilson, & Chin, 2008), which may influence SDM behaviors and contribute to differential experiences of SDM among African-Americans.

Race may also impact SDM through its influence on the patient/provider relationship. In a prior analysis involving African-American diabetes patients, one of the most powerful SDM facilitators was physicians’ interpersonal skills, which were described as essential to establishing a meaningful patient/provider relationship and creating an environment for patients to express concerns and play active roles (Peek, Wilson, Gorawara-Bhat, Quinn, Odoms-Young, & Chin, 2009). Interpersonal skills and relationship-building may be an important way to address the disproportionate physician mistrust among African-Americans (Jacobs, Rolle, Ferrans, Whitaker, & Warnecke, 2006).

Physician mistrust is associated with lower preferences for shared decision-making (Kraetschmer, Sharpe, Urowitz, & Deber, 2004), and in our conceptual model, trust and normative beliefs (e.g. biases) are two mechanisms by which race may influence SDM, either directly or through the patient/provider relationship (Blanchard & Lurie, 2004). For example, providers may have preconceived ideas about who is more likely to prefer an active role, which may influence how engaging they are of different racial/ethnic groups in decision-making. In general, African-Americans have less participatory physician visits with more physician verbal dominance, less information delivery, and less patient-centered communication than whites (Johnson, Roter, Powe, & Cooper, 2004; Epstein, Taylor, & Seage, 1985).

Our study explored patient perceptions about the influence of race on patient/provider communication and specific domains of shared decision-making, an area that has received little attention to date. Consistent with our conceptual model, participants described patient trust, bias/stereotypes and the patient/provider relationship as mediating factors between race and SDM. We also found that race has the potential to negatively influence SDM within each of its domains—information-sharing, deliberation/physician recommendation and decision-making—through cultural discordance, patient beliefs arising from internalized racism, and unconscious provider bias (personally-mediated racism).

While SDM and patient-centered care are associated with health outcomes, the mechanisms are not fully understood. However, we do know that information-sharing and joint goal-setting (important SDM components) are associated with self-efficacy and diabetes self-management, and research suggests that patient understanding, self-efficacy, patient satisfaction and trust predict adherence and self-management, and may be the mechanisms through which shared decision-making impacts health (Heisler, Bouknight, Hayward, Smith, & Kerr, 2002; Heisler, Vijan, Anderson, Ubel, Bernstein, & Hofer, 2003; Piette, Schillinger, Potter, & Heisler, 2003).

Are there potentially effective solutions to address institutional racism, particularly unconscious provider bias?

The question of how to effectively address U.S. racial/ethnic health disparities is an important one, and for which there is no simple or single solution. Rather, the answers must address the range of causes of disparities (e.g. inequalities in education, housing, and health insurance) and empower multiple levers of change (e.g. patients, providers, health systems, policymakers, communities). For example, researchers at the University of Chicago are working to reduce diabetes disparities on the city’s South Side, a predominantly working class African-American community, through a multi-site intervention that combines patient education/activation, provider training, health systems redesign and community engagement (Alliance to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes, 2010).

Our paper focuses on patient-physician communication, and as such, our proposed solutions target patients and physicians. The issue that Bradby (2010) raises about how to address unconscious provider bias is an important one. The training of health providers involved in the Tuskegee syphilis experiment in racial eugenics showed that medical education can create racial bias and exacerbate health disparities (Lombardo & Dorr, 2006). To date, however, no research has shown that physician education through cultural competency training can reduce disparities in health outcomes (Beach, Price, Gary, Robinson, Gozu, Palacio, et al., 2005; Sequist, Fitzmaurice, Marshall, Shaykevich, Marston, Safran et al., 2010). However, such training can improve provider knowledge, attitudes and skills, which may be an important precursor to addressing unconscious provider bias.

There is evidence that with sufficient motivation, cognitive resources and effort, people can inhibit stereotypes and focus on individuals rather than the sociodemographic groups they represent (Blair, 2002; Fiske, Lin, & Neuberg, 1999). Drawing upon evidence in social cognitive psychology, Burgess et al (2007) have outlined strategies and skills for healthcare providers to prevent unconscious racial biases from influencing the clinical encounter. Their framework includes: 1) Enhancing internal motivation and avoiding external pressure to reduce bias, 2) Enhancing understanding of the psychosocial basis of bias, 3) Enhancing providers’ confidence in their ability to successfully interact with socially dissimilar patients, 4) Enhancing emotional regulation skills specific to promoting positive emotions, 5) Increasing perspective taking and affective empathy, and 6) Improving the ability to build partnerships with patients. Teal et al. (in press) developed a medical student elective designed to help manage patient bias that incorporates many of Burgess’ principles; they reported significant improvements in students’ strategies to identify and address their racial biases.

Thus, medical science is currently on the cutting edge of identifying and implementing strategies to reduce unconscious provider bias in healthcare, but much work remains to be done. Addressing such bias is only one of many strategies needed to make strides in eliminating racial/ethnic health disparities.

In summary, Bradby (2010) raises important issues about racism within healthcare and its potential effects on patient/provider communication and health disparities. Yet the evidence is clear: race and racism affect the U.S. healthcare system and the patients and providers that interact within it. Our current study builds upon a large body of evidence and gives voice to the perceptions and experiences of African-Americans with diabetes. Only through continued work to understand racism can we make strides in addressing its effects on healthcare delivery and health disparities.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Monica E. Peek, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL UNITED STATES [Proxy]

Angela Odoms-Young, University of Illinois-Chicago.

Michael T Quinn, The University of Chicago.

Rita Gorawara-Bhat, The University of Chicago.

Shannon C Wilson, The University of Chicago.

Marshall H Chin, The University of Chicago.

References

- Alliance to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes Improving diabetes care and outcomes on the South Side of Chicago. 2010 http://ardd.sph.umich.edu/university_chicago.html.

- Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, Collins TC, Gordon HS, O’Malley K, Peterson LA, Sharf BF, Suarez-Almazor ME, Wray NP, Street RL. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preference or poor communication? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:146–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, Spencer M. An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Ment Health J. 2006;42(6):555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes MW, Feuerstein C, Bass EB, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Cultural Competence: A systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43:356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair IV. The malleability of automatic stereotypes and prejudice. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2002;6:242–261. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard J, Lurie N. R-E-S-P-E-C-T: Patient reports of disrespect in the health care setting and its impact on care. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(9):721–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Jacobs DR, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, Kiefe CI. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the coronary artery risk development in adults study. Am J Epidemiology. 2007;166(9):1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradby . 2010. IN THIS ISSUE. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess D, van Ryn M, Dovidio J, Saha S. Reducing racial bias among health care providers: Lessons from social-cognitive psychology. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:882–887. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0160-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Cooper LA. Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AM, Taylor WC, Seage GR. Effects of patients’ socioeconomic status and physicians’ training and practice on patient-doctor communication. Am J Med. 1985;78:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane TE, Carrese JA. Racial bias in presentation of cases. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:120–121. doi: 10.1007/BF02600511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Lin M, Neuberg SL. The continuum model: ten years later. In: Trope SCY, editor. Dual Process Theories in Social Psychology. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 211–254. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Spencer MS, Chen J, Takeuchi D. A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1275–1282. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, Banaji MR. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DL. Cognitive processes in stereotyping and intergroup behavior. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann LRM, Jeong K, Bost JE, Ibrahim SA. Perceived discrimination in health care and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;23(10):1679–1684. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0730-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, Smith DM, Kerr EA. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M, Vijan S, Anderson RM, Ubel PA, Bernstein SJ, Hofer TP. When do patients and their physicians agree on diabetes treatment goals and strategies, and what difference does it make? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:893–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EA, Rolle I, Ferrans CE, Whitaker EE, Warnecke RB. Understanding African Americans’ views of the trustworthiness of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):642–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klopf DW. Intercultural communication. Morton; Englewood, CO: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kraetschmer N, Sharpe N, Urowitz S, Deber RB. How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision-making? Health Expect. 2004;7:317–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressin NR, Raymond KL, Manze M. Perceptions of race/ethnicity-based discrimination: A review of measures and evaluation of their usefulness for the health care setting. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2008;19:697–730. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde RN, Gardner RC. The intergroup perspective on stereotype organization and processing. Br J Soc Psychol. 1989;28:289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Aiello AE, Leurgans S, Kelly J, Barnes LL. Self-reported experiences of everyday discrimination are associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in older African-American adults. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.11.011. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Everson-Rose SA, Powell LH, Matthews KA, Brown C, Karavolos K, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Jacobs E, Wesley D. Chronic exposure to everyday discrimination and coronary artery calcification in African American women: The SWAN heart study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:362–368. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221360.94700.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo PA, Dorr GM. Eugenics, medical education, and the Public Health Service: Another perspective on the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Bull Hist Med. 2006;80:291–316. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2006.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Segregation and stratification: a biosocial perspective. DuBois Rev Soc Sci Rev Race. 2004;1:7–25. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang E. Diabetes health disparities: A systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5):101S–156S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Odoms-Young A, Wilson SC, Chin MC. How is Shared Decision-Making Defined among African-Americans with Diabetes? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Tang H, Cargill A, Chin MH. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Preferences for Shared Decision-Making. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(S1):41. [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Wilson SC, Gorawara-Bhat R, Quinn MT, Odoms-Young A, Chin MC. Barriers and facilitators to Shared Decision-Making among African-Americans with Diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1135–1139. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1047-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek . 2010. IN THIS ISSUE. [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Bibbins-Domingo K, Schillinger D. Health care discrimination, processes of care, and diabetes patients’ health status. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;60:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Schillinger D, Potter MB, Heisler M. Dimensions of patient-provider communication and diabetes self-care in an ethnically diverse population. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:624–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.31968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren XS, Amick BC, Williams DR. Racial/ethnic disparities in health: The interplay between discrimination and socioeconomic status. Ethn Dis. 1999;9:151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AM, Gee GC, Griffith D. The effects of perceived discrimination on diabetes management. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2008;19:149–163. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2008.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, Shaykevich S, Marston A, Safran DG, Ayanian JZ. Cultural competency training and performance reports to improve diabetes care for black patients. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:40–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith SY, Nelson AR, Smedley BD, Stith SY, Nelson AR, editors. Institute of Medicine. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C: 2002. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teal CR, Shada RE, Gill A, Thompson BA, Fruge E, Villarreal GB, Haidet P. When best intentions aren’t enough: Helping medical students develop strategies for managing bias about patients. J Gen Intern Med. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1243-y. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ. Perceived discrimination and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:553–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZ, Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Schulman KA, Bosworth HB. Perceived discrimination and reported delay of pharmacy prescriptions and medical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:578–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002;40(1):I140–I151. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–828. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Racism and health: a research agenda. Ethn Dis. 1996;54:805–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]