Abstract

Background

Use of lubricant products is extremely common during receptive anal intercourse (RAI) yet has not been assessed as a risk for acquisition of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Methods

From 2006–2008 a rectal health and behavior study was conducted in Baltimore and Los Angeles as part of the UCLA Microbicide Development Program (NIAID IPCP# #0606414). Participants completed questionnaires and rectal swabs were tested for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis with the Aptima Combo 2 assay and blood was tested for syphilis (for RPR and TPHA with titer) and HIV. Of those reporting lubricant use and RAI, STI results were available for 380 participants. Univariate and multivariate regressions assessed associations of lubricant use in the past month during RAI with prevalent STIs.

Results

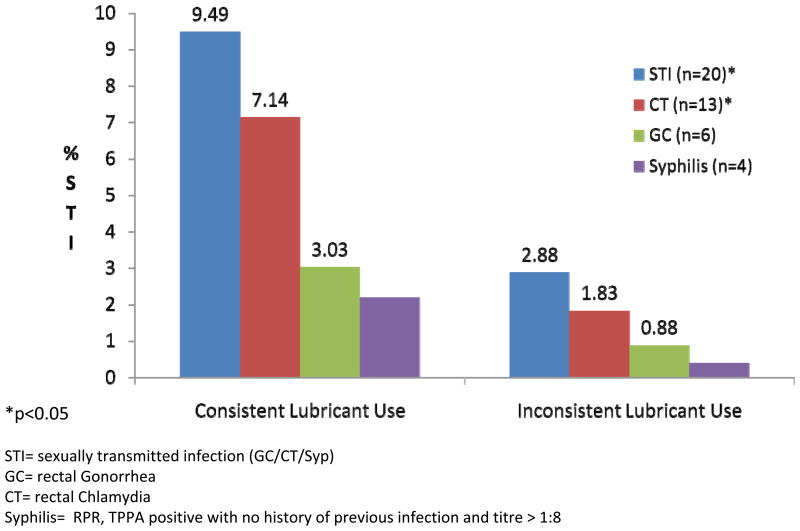

Consistent lubricant use during RAI in the past month was reported by 36% (137/380) of participants. Consistent past month lubricant users had a higher prevalence of STI than inconsistent users (9.5% vs. 2.9%; p=0.006). In a multivariable logistic regression model testing positive for STI was associated with consistent use of lubricant during RAI in the past month (adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 2.98 (95%CI 1.09, 8.15) after controlling for age, gender, study location, HIV status, and numbers of RAI partners in the past month.

Conclusions

Findings suggest some lubricant products may increase vulnerability to STIs. Because of wide use of lubricants and their potential as carrier vehicles for microbicides, further research is essential to clarify if lubricant use poses a public health risk.

Keywords: rectal sexually transmitted infections, lubricants, rectal health

Introduction

Anal intercourse (AI) is a common sexual behavior among men who have sex with men (MSM) 1 and is also practiced by many women2, 3. Recent reviews have reiterated that unprotected receptive anal intercourse (URAI) remains the highest risk method of HIV transmission4–6 Many men and women report use of lubricant products during AI : 59% of respondents reported always using lubricant in a large internet survey of 6,124 men and women reporting AI7 and 89% of MSM in a San Francisco survey reported always using lubricant 8. While there are few international studies of lubricant use, in Peru 48% of MSM reporting RAI in the past 3 months reported lubricant use at last sex9 suggesting use is also high throughout the world among MSM yet may be low among heterosexuals as men in heterosexual couples in a Zambian study reported never using a lubricant product for vaginal sex10. Many individuals also report use of saliva as a lubricant during AI11 in addition to or instead of commercial products or oils or lotions. Lubricants are used to reduce friction during AI, an effect that not only increases sexual pleasure but also facilitates penile penetration.

Concerns about the effects of lubricants on the epithelium are not new. The COL-1492 trial provided evidence that vaginal application of nonoxynol-9 (N-9) use was associated with increased risk of HIV infection, and that rectal administration of N-9 was associated with sloughing of rectal epithelium12, 13,14. Although increased rectal transmission of HIV secondary to N-9 use has never been demonstrated, these findings raised concerns about the potential for other rectal products used during RAI to facilitate HIV transmission. Studies using explant biopsy or surgical samples from humans and animals15 showed some commercial lubricants increased the infection (using laboratory strains of HIV-1) of those tissues when infected in the laboratory and have toxic effects on rectal epithelium16, 17,18. In an important clinical study, gel products similar to those that are commercially available caused short-term denudation of rectal epithelium19, thought to be induced by the lubricant’s osmotic effect on the rectal mucosa. Such injury of the rectal epithelia has been hypothesized to enhance the probability of transmission of pathogens such as HIV and merits additional study.

There is a dearth of data on the frequency as well as types (aqueous-, oil-, silicone-based or numbing) or specific brands of lubricants used in populations practicing AI. Safety data is limited because lubricant products are classified in the US as “medical devices” and in Canada as “cosmetics”, thereby avoiding the safety testing that accompanies drug licensure. There is no existing empirical examination of an effect of rectal lubricant use on rectal health in the context of AI, nor on the probability of rectal infection by an sexually transmitted infection (STI). Given the widespread use of these products in the community and the current focus on rectal-specific formulations of potential new methods of HIV prevention such as microbicides (e.g.: gels that may be similar to existing rectal lubricants), the examination of the association between lubricant use and STI is essential.

Methods

Between October 2006 and June 2009, a rectal health and behaviors study designed to compare the effect of RAI and rectal behaviors on rectal health by gender was conducted as part of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Microbicide Development Program in two community sites in Los Angeles: the AIDS Research Alliance (ARA) and UCLA CARE Clinic and in Baltimore at the Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Eligible, interested individuals recruited from newspaper, internet and clinic posted advertisements and research registries were given further details on the study and provided written informed consent in a private room. The general eligibility criteria was men and women who were at least 18 years of age; willing to be tested for STIs including HIV; willing to undergo an anal exam; and mentally competent to understand study procedures and give informed consent. Criteria by RAI status was defined as no RAI in the past year for the non-RAI men and women. Ror the practicing RAI group it was reported RAI in the past 30 days for men and reported RAI in the past 12 months for women. Men and women were excluded if they were less than 18 years of age; unwilling to be tested for STIs (and HIV); unwilling to undergo an anal exam; unwilling to complete study questionnaire; not mentally competent to understand study procedures and give informed consent; or if they were a male who had no RAI in the past month but did have RAI in the past year.

The study procedures were reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at UCLA, ARA, and JHU. All procedures were also reviewed by the Division of AIDS at National Institutes of Health. Following written informed consent, participants completed computer-administered self interviews about rectal sexual and hygiene behavior and anorectal symptoms, underwent perianal and anorectal examinations including high resolution anoscopy (HRA) to detect anal and distal rectal clinical signs, and were tested for STIs. Rectal swabs were collected and tested for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) with the Aptima Combo 2 assay. Other specimens were collected including blood for syphilis (tested for RPR and TPHA with titer). The study population recruited was intentionally half individuals who were HIV positive with HIV-1 status confirmed in clinic by rapid tests and confirmed by Western Blot. The study population also intentionally was evenly divided by gender and by RAI status so that as described above (n=431 reporting RAI).

Lubricant use was assessed as reported frequency (always, sometimes, never) in the past month during RAI and 620 of 896 male and female participants (69%) provided a response to this question (an additional 244 replied “does not apply and 15 skipped the question); 240 of 620 (39%) were excluded because they responded they never used lubricant for RAI in the past month AND reported no RAI in the past month. The final analysis was conducted on the 380 who reported having RAI in the reference period, provided a response to the lubricant use questions, and for whom there were STI test results. Final analyses utilized a dichotomous variable for lubricant use: those who reported always using lubricant in the past month were coded as “consistent users” versus those who either sometimes or never used lubricant as “inconsistent users”. “Commercial lubricants” were specified as those that participants “can buy in a store or on-line such as KY-jelly.” The definition also specified that using saliva or the lubricant that comes with condoms were not considered “commercial lubricant use”. Participants were then asked to report which lubricants they had used in the past month with choices of “Silicone-based (like Eros brand); water-based (like KY and Wet); Oil-based (like Crisco); Numbing (lubricant that reduces feeling in your butt, vagina, or penis)”. Participants who reported RAI in the past month were also asked if the last time they had RAI they used a commercial lubricant, oil, spit, lotion, a desensitizing lubricant, nothing or other. Condom use was reported for last two RAI events. STI (n=20) was defined as a positive result on a rectal compartment-specific test for a GC (n=6) or CT infection (n=13) or syphilis (positive RPR and TPHA with titre 1:8 or greater and no history of previous diagnosis of syphilis) (n=4).

Bivariate associations between STI and lubricant use in the past month, demographics, HIV status, number of acts of anal intercourse in the past month, numbers of rectal sex partners in the past month and other behaviors were analyzed using univariate logistic regression, chi-square tests, Fisher exact tests and t-tests. Logistic regression was used for univariate and multivariable analyses. All analyses were performed in Stata version 8.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

As described above the sample was intentionally half male, from each city, and HIV positive (Table 1). Distribution of demographic characteristics shows an ethnically diverse sample with almost half African American (53%), a quarter Caucasian (24%), 17% Hispanic/Latino and 6% other race/ethnicity. About one quarter reported being homeless in the past year and 22% were currently unemployed. Half the participants reported a main partner in the past month and less than 5% reported a one-time, unknown or trade partner in the past month. Test results for STI was available for 380 of those reporting RAI lubricant use frequency (227 males and 153 females). Among those reporting RAI in the past month, males reported a slightly higher frequency of acts of RAI in the past month but overall these were not significantly different (mean 5.38, median 2 versus females reported mean of 4.20, median 2.0, p=0.20).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants reporting receptive anal intercourse and consistency of lubricant use

| Full RAI Sample (N=431) | Among those reporting rectal lubricant use in the past month and who have STI data (n=380) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent lube use (N=243) | Consistent lubricant use (N=137) | |||||

| % | N | % | N | % | N | |

| Male* | 53.6 | 231 | 55.5 | 126 | 44.5 | 101 |

| Location: LA | 52.9 | 228 | 65.3 | 130 | 34.7 | 69 |

| HIV Positive | 47.7 | 205 | 62.6 | 122 | 37.4 | 73 |

| Age Group | ||||||

| 18–25 | 13.7 | 59 | 77.1 | 37 | 22.9 | 11 |

| 26–35 | 20.1 | 87 | 62.5 | 45 | 37.5 | 27 |

| 36–45 | 37.3 | 161 | 62.7 | 91 | 37.3 | 54 |

| over 45 | 28.8 | 124 | 60.9 | 70 | 39.1 | 45 |

| Race/Ethnicity* | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 17.6 | 71 | 61.1 | 44 | 39.9 | 28 |

| African American | 52.5 | 212 | 68.1 | 128 | 31.9 | 60 |

| White | 23.5 | 100 | 52.8 | 47 | 47.2 | 42 |

| Other | 6.4 | 26 | 80.7 | 21 | 19.2 | 5 |

| =Homeless past year* | 26.5 | 107 | 72.7 | 72 | 27.3 | 27 |

| < High school education | 17.7 | 78 | 70.8 | 51 | 29.2 | 21 |

| Unemployed* | 22.4 | 92 | 82.1 | 69 | 17.9 | 15 |

| Partner Type | ||||||

| Main | 56 | 218 | 66.2 | 155 | 33.8 | 79 |

| Regular | 12.3 | 48 | 64.3 | 90 | 35.7 | 50 |

| Friend | 14.7 | 57 | 61.7 | 71 | 38.3 | 44 |

| Acquaintance | 7.5 | 29 | 57.1 | 48 | 42.9 | 36 |

| One Time | 4.6 | 18 | 58.7 | 54 | 41.3 | 45 |

| Unknown | 2.1 | 8 | 67.6 | 50 | 32.4 | 24 |

| Trade | 2.8 | 11 | 65.7 | 40 | 34.3 | 21 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age* | 39 | 10.3 | 38.9 | 9.9 | 40.7 | 10 |

| Number RAI partners last month | 2.97 | 7.12 | 3 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 13 |

| Number of times RAI last month | 4.9 | 8.7 | 4.9 | 8.8 | 5.1 | 9.1 |

p-value<0.05

LA=Los Angeles

RAI=receptive anal intercourse

Lube=commercial lubricant

Lubricant Use with RAI

Thirty-six percent (137/380) of participants reported consistent lubricant use when they engaged in RAI in the past month and 64% (224/351) reported use of “commercial lubricant” at last RAI. There were significant differences by gender; fewer women reported consistent use of lubricant in the past month compared to men (24% of women versus 45% of males (p<0.000). There were differences by race/ethnicity (χ=9.6,df=3,p=.02); 47% of Whites, 32% of African Americans, 40% of Hispanics and 19% of ‘Other’ reported consistent use of lubricants. (Table 1). There was no difference in reported frequency of lubricant use among participants who were HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative, or related to interview location (Baltimore vs. Los Angeles). By partner type consistent use of lubricants in the past month was most often reported by those with acquaintance partners and one time partners and less by those with main and one-time partners, but these differences were not significant (Table 1). Significantly fewer of those who were homeless and unemployed reported consistent use than inconsistent use of lubricants. The number of RAI acts in the past month as well as numbers of partners in the past month did not differ among those reporting consistent use of lubricants and those using inconsistently. Those who reported consistent use of commercial lubricant during RAI in the past month were significantly older than those who did not (mean age of 4 vs 38, t-test p-value =0.009).

Rectal STI prevalence

Overall, the prevalence of STI was 5.3% (n=20/380) of those reporting on rectal lubricant use in the past month (6.2% of males and 3.9% of females, difference not significant). Those positive for STI were significantly younger (35.4 years vs 39.7, p=.05); this was true for males (36.7 vs 41.2; p=.05) but borderline for females (32.3 vs 37.7; p=0.09). There was no significant difference by race/ethnicity, HIV status, study city, number of RAI acts in past month, having a main partner in the past month, or number of RAI partners in the past month (Table 2). A third of those with STI also tested positive for GC/CT in their urine based NAAT test (3/17); 30% of those with STI had urethral GC/CT vs 3.7% that did not p<0.007); however, significantly more women were infected in both compartments (44% of those with STI also had cervical infection) whereas few men with rectal STI also had urethral infection (6.7%); none of the men reporting about rectal lubricant use in the past month were infected in both compartments.

Table 2.

Prevalence of rectal sexually transmitted infections including syphilis within groups of study participants

| Rectal GC/CT and Syphils n=20/380 |

No infection n=360/380 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | |||

| Male | 6.2 | 14 | 93.8 | 213 |

| Location: LA | 6.0 | 12 | 94.0 | 187 |

| HIV Positive | 4.1 | 8 | 95.1 | 187 |

| Age Group | ||||

| 18–25 | 6.3 | 3 | 93.8 | 45 |

| 26–35 | 9.7 | 7 | 90.3 | 65 |

| 36–45 | 4.1 | 2 | 95.9 | 139 |

| over 45 | 3.5 | 4 | 96.5 | 111 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 6.9 | 5 | 93.1 | 67 |

| African American | 3.7 | 7 | 96.3 | 181 |

| White | 6.7 | 6 | 93.3 | 83 |

| Other | 7.7 | 2 | 92.3 | 24 |

| =Homeless past year | 7.1 | 7 | 92.9 | 92 |

| < High school education | 5.6 | 4 | 94.4 | 68 |

| Unemployed | 2.4 | 2 | 97.6 | 82 |

| Partner Type | ||||

| Main | 3.8 | 9 | 96.2 | 225 |

| Regular | 2.1 | 3 | 97.9 | 137 |

| Friend | 2.6 | 3 | 97.4 | 112 |

| Acquaintance | 4.7 | 4 | 95.3 | 80 |

| One Time | 6.4 | 7 | 93.6 | 102 |

| Unknown | 6.7 | 5 | 93.2 | 69 |

| Trade | 3.3 | 2 | 96.7 | 59 |

| Mean | SD | |||

| Age* | 35.4 | 9.4 | 39.7 | 9.9 |

| Number of RAI partners last month | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 9.4 |

| Number of times RAI last month | 5 | 11.4 | 5 | 8.7 |

p-value<0.05

Among those reporting RAI

Association of rectal STI and reported lubricant use

There were significantly more STIs detected among those who reported consistent use of lubricant for RAI in the past month than in those reporting inconsistent use (4.1% of those never reporting lubricant, 2.4% of those sometimes using lubricant, and 9.5% of those always using lubricant (p=0.019 Fisher exact test). Consistent lubricant users in the past month also had a higher prevalence of STI than inconsistent users (9.5% vs. 2.9%; p=0.006).

Most participants who reported lubricant use in the past month reported using just one lubricant type at last RAI 64% (239/374), however, 16.6% reported using at least 2 types of lubricants (Table 3). The number of different types of lubricant used in the past month was significantly associated with prevalent rectal GC or CT infection. Those with STI reported greater numbers of lubricants used (mean of 1.23) than those who did not have rectal GC or CT (mean of 0.97 types of lubricants used in the past month; t-test p-value=0.04). Males reported using significantly more lubricants than females in the past month (mean 1.11 versus 0.75, respectively p=.000).

Table 3.

Types of lubricants used among those reporting lubricant use for receptive anal intercourse in past month*

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon-based (e.g., Eros® brand) | 76 | 20.9% |

| Water-based (e.g., brands like KY®, Wet®) | 228 | 61.3% |

| Oil-based (e.g., Crisco®) | 55 | 15.1% |

| Numbing** | 26 | 7.2% |

| Reported 0 types of lubricant | 73 | 19.5% |

| Reported only 1 type of lubricant | 239 | 63.9% |

| Reported 2 types of lubricant | 40 | 10.7% |

| Reported 3 types of lubricant | 22 | 5.9% |

Respondents checked ALL that they used in the past month so sum >100; among only those reporting RAI in past month and lubricant frequency in the past month

Lubricant that reduces feeling in your butt, vagina or penis

Of the participants using lubricants, most reported using a water-based lubricant (61%) while 20% used silicon-based products, 15% oil-based lubricants and 7% said they had used numbing lubricants (Table 3). Efforts to correlate a specific type of reported lubricant use with STI were limited due to small sample sizes. Nevertheless, detected STI was higher in those lubricant users who reported exclusively using water-based lubricants in the past month compared to those used other types of lubricants (6.1% versus 2.7%; p=0.05) and those exclusively using silicone lubricants versus those using other lubricant products (9.2% vs 3.3%, p=.02). There was no difference in those reporting exclusively using oil based lubricants and those who used other lubricants. There were not enough cases of STI by type of lubricant used to assess these differences in multivariate analyses.

There was a difference between those reporting lubricant use at last RAI by condom use at last RAI: fewer condom users reported not using lubricant than non-condom users (27.8% vs. 41.6% 72.2% respectively; p-value=0.014). Among those using condoms at last RAI, there was no difference by frequency of lubricant use reported for the past month. There was no significant difference in STIs between those reporting condom use (4.6% of those reporting condom at last RAI had STI vs 5.4% of those reporting not using a condom at last RAI).

In a multivariable logistic regression model testing positive for STI was associated with consistent use of lubricant during RAI in the past month (adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 2.98 (95%CI 1.09, 8.15) after controlling for age, gender, study location, HIV status, and numbers of RAI partners in the past month. A second model controlled for number of RAI acts in the past month with similar findings; a significant association with lubricant use (AOR 3.41, 95% CI 1.22–9.51) (Table 4). When condom use at last RAI was included in the model the findings remained consistent, however, it was not included in the final mulitvariable models because the time frame was different (not in the last month). Models with and without condom use are presented for reference in Table 4.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of behaviors and characteristics associated with rectal gonorrheal or chlamydial infection or syphilis

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis N=346 | Multivariate analysis N=359 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Age | 0.95 (0.91–1.00) | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.95 (0.89–1.00) |

| Male | 1.61 (0.60–4.28) | 1.47 (0.49–4.41) | 1.88 (0.62–5.68) |

| Los Angeles vs Baltimore | 1.39 (0.55–3.47) | 1.33 (0.48–3.66) | 1.07 (0.39–2.88) |

| HIV positive | 0.61 (0.24–1.53) | 0.92 (0.31–2.70) | 0.87 (0.28–2.63) |

| Number RAI partners in past month | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | -- | 0.98 (0.92–1.05) |

| Number RAI acts in past month | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | -- |

| Condom use at last RAI | 0.77 (0.28–2.28) | -- | -- |

|

| |||

| Always commercial lubricant use for RAI past month* | 3.53 (1.37–9.08) | 3.41 (1.22–9.51) | 2.98 (1.09–8.15) |

Discussion

The use of rectal lubricants for RAI has not been previously assessed in a large observational study as a risk factor for rectal STIs. We report the first epidemiological study to find an association between prevalent STIs and reported use of lubricants for recent RAI; nevertheless this paper reports an association, not causation. While it is not possible to determine the exact act, the exact behaviors practiced, nor the exact route by which an STI was acquired, we used conservative definitions of STIs by restricting our outcome to non-viral STIs most likely acquired through rectal exposure. Our findings also suggest an association between the use of more types of commercial lubricants and prevalent STI among men and women in these two US cities.

Our findings are limited by a lack of a definitive temporal relationship between the reports of lubricant use and the timing of STI acquisition. Only a randomized controlled clinical trial or an observational longitudinal study could better determine such relationships. While clinical trials conducted for rectal microbicide development may shed more light on this, their subjects are randomized to use either an active microbicide product or a gel placebo that is known to be minimally harmful to the epithelium (e.g.: the universal HEC placebo) and participants are counseled to not use other rectal lubricant products. A longitudinal study would be better able to determine STIs that were incident, however, reports would remain based on recall given that assessments of STI would likely be at monthly, six monthly, or yearly intervals. In this study, detection of prevalent infections (during clinic visit) insures that these bacterial infections were likely relatively recently acquired. It should be noted that most of the women with rectal GC or CT also had a positive urine test for GC or CT and it possible that the rectal specimens were contaminated. However, because all women reporting rectal infection also reported having vaginal intercourse, they were likely penetrated by the same infected person in more than one site in the same sexual event or during the same period of time.

Because about 17% of study participants reported using more than one type of lubricant in the past month we could only assess lubricant type by STI among those who reported using just one type of lubricant. Our sample size was too small to allow analysis by those who used different combinations of lubricant types (i.e. used both water-based and silicone-based in the past month). Future studies may have to resort to other epidemiological designs, more detailed behavioral data, and more specific measurement of lubricants types to clarify if specific lubricant types or brands increase risk of STIs more than others.

Anal intercourse has been clearly demonstrated as a behavior widely practiced by men and women and is an important factor in facilitating the HIV and STI epidemics. Clearly, there is a need for rectal microbicide prevention products. Modellers have demonstrated the potential for such interventions for HIV prevention among high risk groups20 and among those who do not use condoms21. The study findings reported here, while specifically defining associations, not causation, contribute to this science by identifying additional factors that may facilitate transmission of STIs, and provide information important to the promotion of better rectal safety and rectal health.

Figure 1.

Percent of Men and Women with Rectal STIs By Lubricant Use Frequency

Acknowledgments

Supported by: UCLA Microbicide Development Program funding by the National Institutes of Health (NIAID IPCP# #0606414)

References

- 1.El-Attar SM, DVE Anal warts, sexually transmitted diseases, and anorectal conditions associated with human immunodeficiency virus. Prim Care. 1999;26:81–100. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans BA, Bond RA, Macrae KD. Sexual behaviour in women attending a genitourinary medicine clinic. Genitourin Med. 1988;64:43–8. doi: 10.1136/sti.64.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strang J, Powis B, Griffiths P, Gossop M. Heterosexual vaginal and anal intercourse amongst London heroin and cocaine users. Int J STD AIDS. 1994;5:133–6. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox J, Fidler S. Sexual transmission of HIV-1. Antiviral Res. 2010;85:276–85. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dosekun O, Fox J. An overview of the relative risks of different sexual behaviours on HIV transmission. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:291–7. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a88a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varghese B, Maher JE, Peterman TA, Branson BM, Steketee RW. Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: quantifying the per-act risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:38–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Javanbakht M, Murphy R, Gorbach P, Leblanc MA, Pickett J. Preference and practices relating to lubricant use during anal intercourse: implications for rectal microbicides. Sex Health. 2010;7:193–8. doi: 10.1071/SH09062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carballo-Diéguez A, O’Sullivan LF, Lin P, Dolezal C, Pollack L, Catania J. Awareness and attitudes regarding microbicides and Nonoxynol-9 use in a probability sample of gay men. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:271–6. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinsler JJ, Galea JT, Peinado J, Segura P, Montano SM, Sánchez J. Lubricant use among men who have sex with men reporting receptive anal intercourse in Peru: implications for rectal microbicides as an HIV prevention strategy. International Journal of STD & AIDS Volume. 2010;21:567–72. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones DL, Weiss SM, Chitalu N, et al. Acceptability and use of sexual barrier products and lubricants among HIV-seropositive Zambian men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:1015–20. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler LM, Osmond DH, Jones AG, Martin JN. Use of saliva as a lubricant in anal sexual practices among homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:162–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819388a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Damme L, Ramjee G, Alary M, et al. Effectiveness of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on HIV-1 transmission in female sex workers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:971–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips DM, Sudol KM, Taylor CL, Guichard L, Elsen R, Maguire RA. Lubricants containing N-9 may enhance rectal transmission of HIV and other STIs. Contraception. 2004;70:107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabet SR, Surawicz C, Horton S, et al. Safety and toxicity of nonoxynol-9 gel as a rectal microbicide. Sex Trans Dis. 1999;26:564–71. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adriaens E, Remon JP. Mucosal irritation potential of personal lubricants relates to product osmolality as detected by the slug mucosal irritation assay. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:512–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudol KM, Phillips DM. Relative safety of sexual lubricants for rectal intercourse. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:346–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200406000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo J, Rohan LC, Moncla B, et al. Microbicides 2010. Pittsburgh, PA: 2010. Safety and Anti-HIV Activity of Over-the-Counter Lubricant Gels. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begay O, Jean-Pierre N, Abraham C, et al. Microbicides 2010. Pittsburgh, PA: 2010. Preliminary Evaluation of Toxicity and Antiviral Properties of Personal Lubricants. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuchs EJ, et al. Hyperosmolar sexual lubricant causes epithelial damage in the distal colon: potential implication for HIV transmission. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:703–10. doi: 10.1086/511279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breban R, McGowan I, Topaz C, Schwartz EJ, Anton P, Blower S. Modeling the potential impact of rectal microbicides to reduce hiv transmission in bathhouses. Math Biosci Eng. 2006;3:459–66. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2006.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boily M-C. Population-level impact of microbicides to prevent HIV: the efficacy that matters?. Microbicides 2010 Conference; Pittsburgh. 2010. p. 176. Symposium presentation. [Google Scholar]