Abstract

Summary: Increasing number of ChIP-seq experiments are investigating transcription factor binding under multiple experimental conditions, for example, various treatment conditions, several distinct time points and different treatment dosage levels. Hence, identifying differential binding sites across multiple conditions is of practical importance in biological and medical research. To this end, we have developed a powerful and flexible program, called DBChIP, to detect differentially bound sharp binding sites across multiple conditions, with or without matching control samples. By assigning uncertainty measure to the putative differential binding sites, DBChIP facilitates downstream analysis. DBChIP is implemented in R programming language and can work with a wide range of sequencing file formats.

Availability: R package DBChIP is available at http://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~kliang/DBChIP/

Contact: kliang@stat.wisc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

ChIP-seq (Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing) is widely used in studying protein–DNA binding on a genome-wide scale. After cross-linking, immunoprecipitation and shearing, millions of sequenced DNA fragments (reads) are mapped to a reference genome, and sites with over-abundant reads are declared as putative binding sites. We focus on an important class of binding sites that have similar read profiles throughout the genome. Specifically, the lengths of the binding sites are similar across the genome, and their centers are well defined. These binding sites tend to have read profiles that look like sharp peaks. This class includes transcription factor binding and some histone modifications measured by ChIP-seq.

Most of the available ChIP-seq peak-finding programs identify transcription factor binding sites in a single ChIP sample with or without a matching control sample; for a review, see Wilbanks and Facciotti (2010). An increasing number of experiments are investigating differential binding across two or more experimental conditions, including but not limited to, multiple treatments (Zhong et al., 2010), series of time points (Niu et al., 2011), and multiple cell lines (Kasowski et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2010). Since transcription factors regulate gene expression, differential binding across multiple experimental conditions is critical for revealing the function of a transcription factor at each binding site. Thus, a program that can detect differential binding of transcription factors across multiple conditions is much needed.

2 METHODS

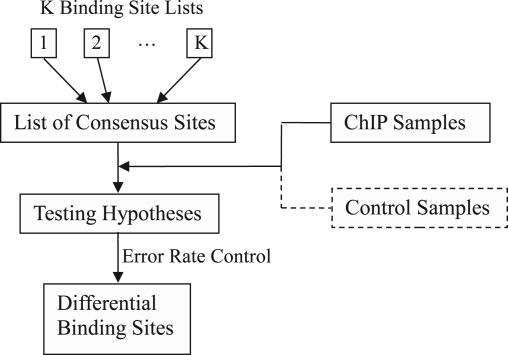

Suppose there are a total of K conditions, each with one ChIP sample and possibly one matching control sample, for comparison. The workflow of DBChIP is illustrated in Figure 1. DBChIP works with existing ChIP-seq peak-finding programs for identifying binding sites in any individual condition. Most ChIP-seq programs can output a list of predicted binding site locations along with scores indicating the strengths of binding for a given ChIP sample. DBChIP first merges the lists of predicted binding locations from multiple conditions into one single list by clustering close-by sites into consensus sites. Then a hypothesis of non-differential binding is tested at each consensus site. If a matching control sample is available for each ChIP sample, the test can be further improved by directly applying to the estimated binding signal read counts. We briefly describe each step in the remainder of this section. Further details are discussed in the Supplementary Material.

Consensus site: binding site predictions can be obtained under each condition through one of many existing ChIP-seq programs. However, it is unlikely that the predictions for the same binding site across different conditions are exactly the same. To obtain consensus sites, we first pool all the predicted binding site locations of different conditions together. Next we employ agglomerative hierarchical clustering with centroid linkage to group predicted locations into different clusters. Then, the consensus site positions are calculated as the average of predicted locations within each cluster, weighted by their scores if available. The read count for each binding site is defined as the sum of the number of 5′ ends on the positive strand within the upstream window [s−w, s−1] and the number of 5′ ends on the negative strand within the downstream window [s+1, s+w], where s is the consensus site position and w is a configurable window size parameter.

Detecting differential binding: to control the probability of falsely declaring differentially bound sites, we formally test a null hypothesis of non-differential binding at each consensus site. The tests are generally carried out through a generalized linear model with Negative Binomial distribution to account for the over-dispersion among samples. When replicates are available, the dispersion parameter in the Negative Binomial distribution is estimated through edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010). We develop novel methods to account for potential over-dispersion in the absence of replicates. Details are provided in Section 1.2 of the Supplementary Material. We obtain a P-value and fold change estimates between conditions for each site, and DBChIP can then report significantly differentially bound sites according to a pre-specified false discovery rate (FDR) threshold. There are also graphical functions in DBChIP to plot binding profiles for visual inspection; examples can be found in Supplementary Figures S5, S6, and S8.

Control samples: in many ChIP-seq datasets, ChIP samples are accompanied with matching control samples to improve peak detection. The ChIP reads in a binding site can be decomposed into binding signal reads and background noise reads (Xu et al., 2010; Supplementary Fig. S1). Arguably, it is of more interest to detect the differences among the binding signal reads across conditions than to detect the differences of all reads (signal+noise), because the latter may be attributed to the differences in the background noise reads across conditions. Without control samples, the tests performed in (ii) need to implicitly assume that the background reads across ChIP samples are comparable. Such an assumption may be reasonable for some datasets, but cannot be taken for granted in general. Since matching control samples provide natural estimates of the background noise read counts, we replace the total read counts at binding sites with the estimated signal counts (ChIP−control) and test for differential binding as in (ii).

Fig. 1.

Workflow of DBChIP.

3 EXAMPLE

Zhong et al. (2010) studied binding of the transcription factor PHA-4 in C.elegans under two developmental conditions: embryonic and the first stage of larval development (L1) under starvation conditions. The authors first identified 4350 binding sites in embryos and 4808 in starved L1 larvae and then treated non-overlapping sites as differential binding sites. This simple approach can have two potential pitfalls. First, the sites that are bound in all conditions but have different binding strengths will not be captured as differentially bound. Second, binding sites identified in one or more but not in all conditions (differentially bound sites) may be a result of potential false negatives in some conditions.

Our application of DBChIP on this dataset revealed that 139 of the 1742 binding sites identified as bound in both conditions show differential binding after FDR control at 0.05 level. This result is further supported by observing that the median fold changes for favorable binding in embryonic and L1 conditions are both >3.5 fold. These differences in binding strengths may be attributable to the differential activity of important binding co-factors of PHA-4 under the embryonic and L1 stages. In contrast, among the 2608 binding sites declared bound in the embryonic condition only, 1361 of them have P>0.05 and are unlikely to be declared differentially bound using any error rate control method at level 0.05 (see Supplementary Fig. S2 for an example). Similarly, 864 out of 3066 L1 only binding sites have P>0.05. DBChIP also provides estimated fold changes between the ChIP samples in addition to differential binding calls; hence, the downstream analysis can be based on both P-values and fold changes. Further details are in Section 2 in Supplementary.

4 DISCUSSION

In summary, DBChIP detects differential binding in a quantitatively principled way by formally testing hypothesis of non-differential binding at each putative binding site. DBChIP assigns uncertainty measure (P-values) to each finding, and thus, proper error rate control can be achieved. Furthermore, when there are more than two conditions for comparison (K>2), DBChIP can be used to detect pairwise differences after the detection of overall differential binding. Moreover, DBChIP does not rely on a specific sequencing platform and can accommodate data from Illumina, SOLiD and other platforms.

Funding: National Institutes of Health grant HG003747 and Department of Energy grant FG02-04ER25627.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Kasowski M., et al. Variation in transcription factor binding among humans. Science. 2010;328:232–235. doi: 10.1126/science.1183621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu W., et al. Diverse transcription factor binding features revealed by genomewide ChIP-seq in C. elegans. Genome Res. 2011;21:245–254. doi: 10.1101/gr.114587.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M., et al. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbanks E., Facciotti M. Evaluation of algorithm performance in ChIP-seq peak detection. PloS One. 2010;5:e11471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., et al. A signal-noise model for significance analysis of ChIP-seq with negative control. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1199–1204. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W., et al. Genetic analysis of variation in transcription factor binding in yeast. Nature. 2010;464:1187–1191. doi: 10.1038/nature08934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong M., et al. Genome-wide identification of binding sites defines distinct functions for Caenorhabditis elegans PHA-4/FOXA in development and environmental response. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]