Abstract

Motivation: Multifunctional proteins perform several functions. They are expected to interact specifically with distinct sets of partners, simultaneously or not, depending on the function performed. Current graph clustering methods usually allow a protein to belong to only one cluster, therefore impeding a realistic assignment of multifunctional proteins to clusters.

Results: Here, we present Overlapping Cluster Generator (OCG), a novel clustering method which decomposes a network into overlapping clusters and which is, therefore, capable of correct assignment of multifunctional proteins. The principle of OCG is to cover the graph with initial overlapping classes that are iteratively fused into a hierarchy according to an extension of Newman's modularity function. By applying OCG to a human protein–protein interaction network, we show that multifunctional proteins are revealed at the intersection of clusters and demonstrate that the method outperforms other existing methods on simulated graphs and PPI networks.

Availability: This software can be downloaded from http://tagc.univ-mrs.fr/welcome/spip.php?rubrique197

Contact: brun@tagc.univ-mrs.fr

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks highlight the modularity of cellular processes and allow deciphering protein functions at the cellular level. Since PPI networks can be represented as simple graphs where a vertex corresponds to a protein and an edge to a direct physical interaction, graph partitioning methods have been proposed to highlight groups of densely connected vertices (Brun et al., 2003, 2004; Newman, 2004, 2006; or Aittokallio and Schwikowski, 2006 for a review). Identified clusters are usually designated as ‘functional modules’, i.e. groups of proteins involved in the same pathway or the same cellular process. Although successful in predicting the function of uncharacterized proteins (Sharan et al., 2007), these methods lead to ‘strict’ partitions, in which each vertex (protein) belongs to exactly one cluster (functional module). Clearly, the logic of strict partitions does not always represent the biological reality. For instance, some proteins perform different cellular functions and consequently contribute to pleiotropic phenotypes when mutated (Hodgkin, 1998). Such multifunctional proteins are expected to specifically interact with distinct sets of partners, either simultaneously or not, depending on the function performed. ‘Strict’ partitions, however, do not allow a protein to belong to several clusters. Another limitation is encountered with protein complexes whose composition and function may vary according to the context and conditions (Kühner et al., 2010). Addressing some biological questions, therefore, requires methods leading to ‘overlapping’ clusters, that allow vertices to be ‘multi-clustered’.

Overlapping clustering first appeared three decades ago with theoretical studies on distance analyses (Bandelt and Dress, 1989; Barthélemy and Brucker, 2001; Diatta and Fichet, 1998; Diday, 1986; Fichet, 1986; or, for an extensive review, Brucker and Barthélemy, 2007). These methods have not been intensively developed and consequently, have not been as successful as hierarchical and partitioning methods. With respect to biological networks, although the overlapping nature of biological communities has been recognized (Ahn et al., 2010; Palla et al., 2005), only few methods leading to overlapping clusters have been proposed (Adamcsek et al., 2006; Ahn et al., 2010; Kovacs et al., 2010). None of these methods, however, has been extensively used to answer biological questions: CFinder contributed to the identification of protein complexes from AP/MS data (Kühner et al., 2010) and Link Communities helped predict a set of prostate cancer genes (Ahn et al., 2011).

In this work, we present OCG (Overlapping Cluster Generator), a novel method to cover a PPI network with relevant overlapping clusters. By applying our method to the human PPI network, we show that multifunctional proteins are revealed at the intersection of clusters. Finally, we show that our method outperforms other existing methods (Adamcsek et al., 2006; Ahn et al., 2010) both on simulated graphs and on PPI networks.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Datasets

A high confidence dataset of 27 286 binary interactions involving 9596 proteins was built by joining (i) 2325 human interactions manually extracted from the literature and (ii) 24 961 binary interactions from the APID database [Prieto and De Las Rivas (2006), http://bioinfow.dep.usal.es/apid/]. Interactions identified by at least one experimental method leading to the detection of binary interactions were selected (Souiai et al., 2011). To improve clustering efficiency, proteins involved in a single interaction were recursively removed from the network. Following this pruning process, we obtained a human PPI network with 24 027 interactions between 6172 proteins (Supplementary Material 4). On average, each protein interacts with 7.8 partners. The lists of disease genes and cancer genes were taken from Goh et al. (2007), and Futreal et al. (2004), respectively.

2.2 Protein domain prediction

The complete set of Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) for all domains in PfamA and PfamB were downloaded from the Pfam database (Finn et al., 2010). We then used HMMER3 to scan each of the sequences in our network for domains.

2.3 Simulations

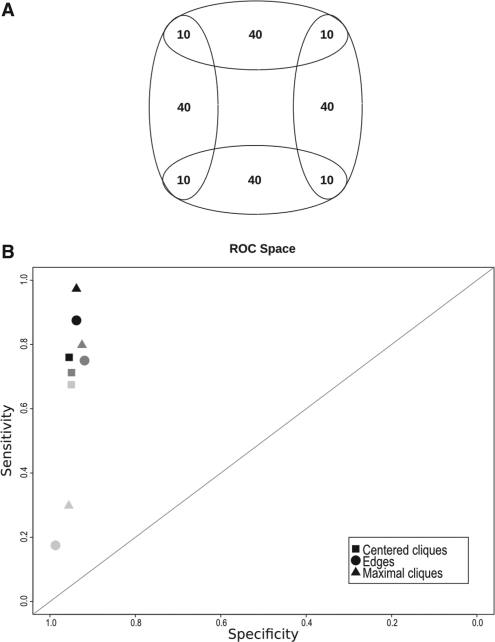

A set of random graphs was created using an overlapping partition (Fig. 2A) of 200 vertices as a model. The four overlapping regions contain 10 vertices each. Therefore, 40 vertices have to be multiclustered and 160 monoclustered. Several models of random graphs have been tested to obtain graphs corresponding to inter-cluster edge probabilities 0.15, 0.20 and 0.25. The different models are Erdös-Rényi, Random spanning trees (several random spanning trees are selected in each cluster to match the required density) and Geometric random selection in a 3D Euclidean space [Geo3D Przulj et al. (2004)] adapting the distance threshold to the desired cluster density. The vertices composing the intersections were selected uniformly in [0.2, 0.8]3 space in order to fit the partition model of Figure 2A. Three sets of 100 graphs with an equivalent number of edges, corresponding to the three probability values, have been generated for each model. pi<0.15 causes graph disconnection.

Fig. 2.

(A) Theoretical partition composed of 200 vertices. The four overlapping regions contain 10 vertices each. (B) Comparison of OCG performance, according to the initial class system chosen, when applied to simulated graphs with different edge probabilities (Pi=0.15, 0.20, 0.25, from light grey to black). Results are represented in ROC space.

2.4 Sensitivity, specificity

The sensitivity and specificity of each method were assessed by comparing the obtained results to the expected theoretical partition, according to the following formulas:

2.5 Method parameters

CFinder 2.0.4 (downloaded from http://cfinder.org/) was used with different parameters depending on graph topology. On the biological PPI network, k=3 led to the best partition, with the best trade-off between coverage and number of multiclustered nodes. For simulated graphs, k=4 was used for low-density graphs (pi=0.15, 0.20, 0.25), k=5 for pi=0.30, 0.35; k=6 for pi=0.40, 0.45; k=7 for pi=0.50. Link Communities (downloaded from http://barabasilab.neu.edu/projects/linkcommunities/) was used with default parameters, automatically cutting the hierarchical tree at the point where the density function of the partition is maximized.

3 ALGORITHM: ESTABLISHING OVERLAPPING CLUSTERS

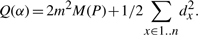

3.1 Selecting a criterion: Modularity M(P), Integer Modularity Q(α)

Clustering methods in communities aim at identifying vertex classes with a large number of internal edges relative to their cardinality. For this, the excess of internal edges relative to the number of edges expected for a random partition into classes having the same number of elements, is often quantified using the modularity criterion defined by Newman for strict partitions (Newman, 2004).

Let G=(V, E) be a simple connected graph with n vertices and m edges (|V|=n, |E|=m) and P be a partition of V into p classes: P={V1, V2,.. Vp}. Let eij be the percentage of edges having one end in class Vi and the other in class Vj: eij=|E∩(Vi×Vj)|/m. The probability for a random edge to have one end in Vi is equal to:

The modularity of partition P is defined as:

An equivalent criterion has been established to extend the modularity function to overlapping classes. Let dx be the degree of vertex x in G and A its incidence matrix (Axy=1 iff (x, y)∈E). We denote B the matrix:

It can be noted that all the B values corresponding to non-connected pairs of vertices are negative, while those corresponding to the edges of G (Axy=1) are positive or null, except if dxdy>2m. We will admit in the following that dxdy≤2m, as this is the case in PPI graphs known.

An overlapping class system can be defined by a binary relation α: V×V→{0, 1}, such that αxy=1 if both x and y belong at least once to a common class and 0 otherwise. Angelelli and Reboul (2008) have proved that quantity:

extends Newman's modularity to overlapping classes. Interestingly, the relation α is defined for both strict and overlapping class systems covering a graph. This formulation allows a good understanding of this new modularity function.

- When the binary relation α is transitive and defines a partition P,

Q(α) is thus an affine function of M, and it is equivalent to maximize M or Q.

When merging classes Vi and Vj, only the values αxy such that elements x∈Vi and y∈Vj are newly joined together, are modified. The sum of the corresponding Bxy values is added to modularity Q. The modularity function increases if and only if this sum is positive.

- Q is upper bounded by the sum of the positive values in B:

Qmax is thus reached for any class system composed of all edges and exclusively edges, as for the set of maximal cliques or simply the set of all edges.

3.2 A hierarchy of overlapping classes

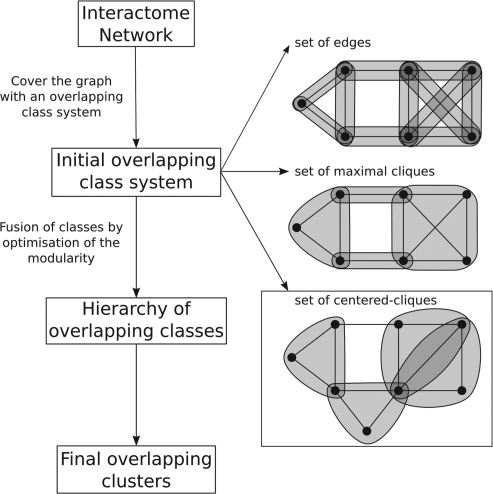

The principle of OCG, is to build a tree in which the leaves are initial classes that are progressively and hierarchically joined (Fig. 1). To avoid confusion between the initial and final overlapping classes, we will hereafter refer to the latter as clusters.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the OCG algorithm. The graph is covered by an initial overlapping class system. The initial classes are hierarchically fused optimizing the modularity of the partition, leading to overlapping clusters.

In Newman's algorithm that maximizes the modularity over the set of strict partitions (Newman, 2006), the starting point is the set of singletons in V. This initial partition has a null modularity, since there are no internal edges. Then, while modularity increases, the two clusters Vi and Vj whose union gives the positive maximal gap are merged: Vi and Vj are deleted and replaced by Vi∪Vj. The gap is equal to the difference between the modularity values when clusters Vi and Vj are separated or joined together. A hierarchy of nested clusters is built iteratively, and the algorithm stops when no further fusions can produce a gain in modularity.

The modularity formula Q allows adapting this hierarchical process to overlapping initial classes and merging them according to a similar greedy strategy. At each step, the joined clusters are those maximizing the average gain. Using this average value, defined as the global modularity gain divided by the number of newly joined vertex pairs, allows avoiding the chain effect that adds elements one by one and produces clusters inappropriate for subsequent functional prediction.

The merging process is stopped either by setting the expected number of clusters, or by bounding the maximal cluster's cardinality or by maximizing the modularity. Note that the latter cannot be used systematically because the modularity function may decrease or not be monotonous with respect to the chosen initial class system (see next paragraph).

At the end, an optimization step is added: the contribution of each element to the modularity of the clusters is measured. When negative, the element is transferred to the cluster where its contribution is the highest. This filtering process permits eliminating loosely assigned elements and therefore further improving both the modularity value and the performance of the method.

3.3 Choosing an initial class system

For any graph, there are four main natural covering class systems: (i) singletons, which generate disjoint clusters and are therefore not appropriate for our objective; (ii) edges, which give a large number of initial classes; (iii) maximal cliques, which can be very demanding computationally; and (iv) adjacency lists, which do not allow optimizing modularity because highly connected nodes contribute to negative modularity values.

Obtaining overlapping clusters thus implies either using edges or maximal cliques:

The maximal cliques of graph G: can be computed for large PPI graphs because such networks are very sparse. When the list of the maximal cliques is computed, a class system of modularity Qmax is formed. Any class fusion will contribute to Q decrease until Qmin = ∑x=1..ndx2.

The edges of G: the modularity of the system is maximal and the merging process begins by establishing cliques. The modularity function increases as long as the algorithm finds two clusters Vi and Vj such that ∀(x, y)∈Vi×Vj, (x, y)∈E.

The efficiency of the algorithm depends on the number K of initial classes, since K corresponds to the number of iterations. Each iteration requires O(K2)+O(n2) operations. As for most hierarchical schemes, the global complexity is in O(K3) in time and O(K2) in memory space. Given this O(K3) complexity, starting from an huge initial class system based on edges or maximal cliques leads to excessive computation times. To reduce the number of initial classes, we propose to limit K to the number of vertices n, thereby introducing the centred clique system.

The centred cliques: for each vertex x∈G, a clique is built using a greedy polynomial algorithm. As long as a clique is produced, vertices adjacent to x are added in decreasing order of their relative degree. The resulting clique, containing x, is not necessarily maximal since a larger one containing x could exist. After the elimination of the included sets, at most n distinct initial classes remain, thus reducing the computation time (Algorithm in Supplementary Material 1).

-

Initial class system assessment: the ability of the three initial class systems to produce relevant sets of overlapping clusters has been evaluated by applying OCG to random graphs with different probabilities of edges (see section 2). These graphs are composed of 200 vertices distributed in four overlapping theoretical clusters, according to the partition schema shown in Figure 2A. Results are represented in ROC space (Fig. 2B) to compare the theoretical clusters to those obtained by OCG (see section 2).

For each initial class system, the false positive rate is very low and the number of true positive tends to be underestimated when the edge probability is low. However, sensitivity drastically drops with edge probability (i.e. graph density) except when graphs are covered with the centred clique system. We have, therefore, chosen this system for further studies. Note that PPI networks have a lower edge density (47 times lower than simulated graphs for the human PPI network investigated herein) that cannot be simulated without disconnecting the graph. Finally, the centred clique system is the least time and memory consuming.

4 RESULTS: MULTIFUNCTIONAL PROTEINS ARE REVEALED AT THE INTERSECTION OF CLUSTERS

4.1 Applying OCG to the human PPI network

A large human PPI network of 24 027 interactions between 6172 proteins has been partitioned by OCG, using the centred clique system to initially cover the graph. The fusion process was stopped when the maximal modularity was reached. Ultimately, 396 overlapping clusters containing 31.4 proteins on average were obtained (Supplementary Material 2). Overall, a third of the network's proteins belong to several clusters (2104/6172, Supplementary Material 3).

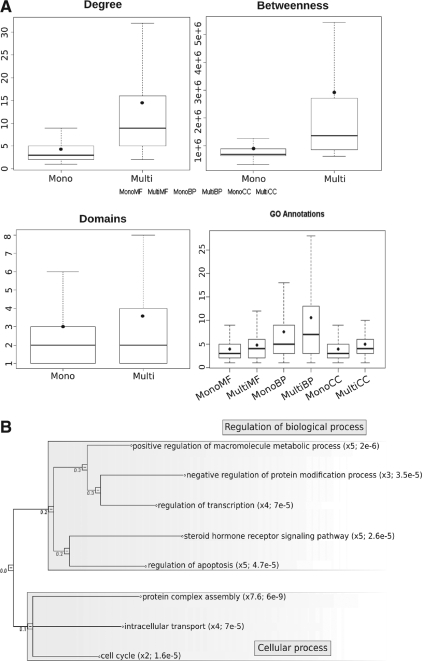

4.2 Functional and topological features of multi- versus monoclustered proteins

Next, we asked whether topological and functional features can distinguish multi- from monoclustered proteins (Fig. 3A). On average, multiclustered proteins have a higher degree and a higher node betweenness (Wilcoxon test, p−val≤2.2e−16). Multi- and monoclustered proteins have no significant difference in length. Nevertheless, multiclustered proteins contain more domains than monoclustered (3.6 versus 3, p−val=3e−6). This is reflected by the number of Gene Ontology (GO) terms annotating multiclustered proteins. In all three GO subontologies (Molecular Function, Cellular Component and Biological Process), multiclustered proteins are, on average, annotated to more terms than monoclustered (p−val≤2.2e−16). Multiclustered proteins, therefore, appear to be involved in a larger number of processes than monoclustered.

Fig. 3.

(A) Topological and functional features of multi- versus monoclustered proteins. For each feature, the distributions of mono- and multiclustered proteins are represented by boxplots (line = median; dot = mean). (B) Gene Ontology terms overrepresented among multiclustered proteins [Image created by SimCT (Hermann et al., 2009)].

The detailed analysis of the annotations of each protein group shows interesting qualitative differences. While there are no overrepresented terms among the annotations of monoclustered proteins in any of the subontologies (data not shown), multiclustered proteins are enriched in Biological Process GO terms referring to regulatory functions and protein complex assembly (Fig. 3B). This observation is confirmed by the statistical overrepresentation of the Molecular Function GO terms related to transcription regulator activity, enzyme- and receptor-binding activities (p−val=1.4e−5, 3.4e−4 and 2.4e−3, respectively) and of proteins participating in protein complexes (enrichment 2.2, p−val=7.4e−70) (data not shown). Finally, products of cancer genes are also enriched among multiclustered proteins (enrichment 2.6, p−val=7.4e−15), whereas proteins involved in other types of diseases are not (see Materials and Methods for details).

To sum up, these results show that multiclustered proteins are more central in the network, contain more domains and are involved in a large number of—mainly regulatory—processes, all features that can be considered as hallmarks of multifunctional proteins. Therefore, the OCG algorithm appears to detect multifunctional proteins in cluster intersections. This conclusion is emphasized by the fact that the 10 most multiclustered proteins are bona fide multifunctional proteins involved in general regulatory functions (ubiquitination, regulation of transcription and signaling) and are consequently involved in numerous biological processes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Top 10 multiclustered, bona fide multifunctional proteins and the number of clusters each belongs to

| Protein names | Clusters |

|---|---|

| UBQL4, ubiquilin-4 | 53 |

| P53, cellular tumor antigen p53 | 46 |

| SMAD2, mother against decapentaplegic homolog 2 | 38 |

| EP300, histone acetyltransferase p300 | 36 |

| SMAD3, mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 | 36 |

| SMAD9, mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 9 | 35 |

| TRAF2, TNF receptor-associated factor 2 | 34 |

| EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor | 33 |

| CBP, CREB-binding protein | 33 |

| TGFR1, TGF-beta receptor type-1 | 33 |

5 COMPARISON TO OTHER METHODS

We compared the performance of the OCG partitioning algorithm to other methods, based on different principles that also lead to overlapping clusters. CFinder (Adamcsek et al., 2006) uses a Clique Percolation Method (Palla et al., 2005) in which the k cliques are computed and two vertices are in the same cluster if a path going through (k−1) cliques exists between them. Link Communities (Ahn et al., 2010) applies a hierarchical clustering process to the line graph (edge duality), equivalent to our initial class system when corresponding to the edges of G.

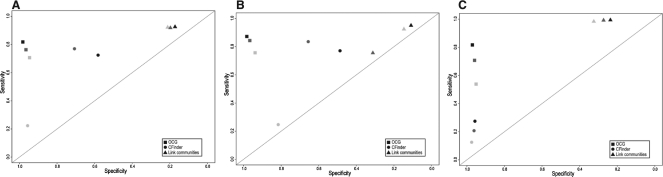

5.1 Simulated graphs

The three methods were applied to random graphs of different edge densities simulated according to several models: Erdös-Rényi, Random spanning trees and Geometric random graphs [Geo3D, Przulj et al. (2004)] (see Section 2). When the two first models are used (Fig. 4A and B), improving sensitivity costs a loss of specificity for CFinder and Link Communities, while OCG's performance remains relatively stable. When the GeO3D model is used (Fig. 4C), OCG offers the better trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. In addition, OGG's performance is only slightly affected by the edge density of the simulated graphs (Fig. 4A–C). OCG, therefore, fares better on low edge density, such as PPI, graphs than the other methods. In order to take into account the number of clusters generated by the methods in the evaluation scheme, we computed the accuracy value proposed by Brohée and van Helden (2006). In all cases, OCG performs better (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the performances of CFinder, Link Communities and OCG when applied to different random graphs (A) Erdös-Rényi; (B) Random spanning trees; (C) Geo3D with different edge probabilities (pi=0.20, 0.25,…, 0.45, 0.50, from light grey to black). Results are represented in ROC space.

Finally, a negative control shows that the performance of all three methods is close to random when either the nodes or the edges of the simulated graphs are shuffled with the 3 tested models (Supplementary Fig. 2).

5.2 Human PPI network

All three methods were applied to the human interactome. In the absence of a dataset of bona fide multifunctional proteins with which the methods could be benchmarked, we reasoned that proteins multiclustered by all three methods are the most likely candidates for multifunctionality. We therefore calculated, for each of the three methods, what percentage of the top 5% most multiclustered proteins was also multiclustered by the other two methods (Table 2). The results obtained are similar to the performances recorded on simulated graphs. Although most proteins multiclustered by CFinder are also found by the other two methods (high specificity), these are very few in number (low sensitivity). For Link Communities, on the other hand, only a third is found by the other methods (high sensitivity/low specificity). By this standard, therefore, OCG has a good trade-off between sensitivity and specificity because half of the proteins multiclustered by OCG are found by both other methods and all are found by at least one.

Table 2.

Percentage of the top 5% most multiclustered proteins identified by each method that were multiclustered by the tested method and both others (MC3), by the tested method and one other (MC2), and by the tested method alone (MC1)

| Method | Top 5 (%) | MC3 (%) | MC2 (%) | MC1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCG | 104 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| CFinder | 24 | 92 | 8 | 0 |

| Link Com | 149 | 36 | 52 | 12 |

Finally, we have shown that OCG tends to multicluster those proteins with a higher number of domains and GO annotations while monoclustering those with less (Fig. 3). Although the other methods show the same trend (Supplementary Figs S3 and S4), the Wilcoxon test P-values indicate that OCG is better at discriminating between multi- and monoclustered proteins.

6 DISCUSSION

Graph partitioning can lead to ambiguous results where a node is assigned to one particular cluster but could, just as well, have been assigned to another. This situation is often due to the structure of the graph under study and is particularly encountered during analyses of PPI networks. Indeed, although the modularity of these networks allowed identifying clusters of proteins acting together in particular biological processes using appropriate graph partitioning, the uniqueness of node classification impedes revealing the involvement of some proteins in multiple processes. The reality of PPI networks, therefore, is more accurately described by allowing modules (clusters) to overlap. To deal with this dual nature of PPI graphs (both modular and overlapping), we have developed the OCG algorithm described herein, a method to cover graphs with overlapping clusters based on the optimization of the modularity. We propose covering the graph with centred cliques that we iteratively fuse. This initial class system outperforms the recently developed Link Communities algorithm (Ahn et al., 2010) (Fig. 4), which aims at capturing the overlapping structure of the graph by grouping similar edges into a hierarchy. OCG, therefore, appears better at grasping the overlapping nature of graphs with low density of edges, such as PPI networks.

Currently available PPI networks represent only a subset of all PPIs in a given cell. Therefore, the topological structure of the entire interactome is still unknown and under debate. A direct consequence of this uncertainty is the lack of ‘real’ partitions against which we could test the efficacy of our methods. Therefore, simulations have been performed using several models of random graphs (Kuchaiev and Przulj, 2009). In this context, we chose to: (i) design a graph with overlapping communities to be recovered, (ii) build simulated graphs corresponding to this system, according to three different models and (iii) apply the methods mentioned here on each of the simulated graphs. This approach allowed us to test the performance of each method on a difficult problem in which each cluster to be found shares nodes with two other clusters. Since the simulated graphs with overlapping communities might not faithfully reflect the biological reality (i.e. proteins may be involved in more than two processes), we verified that multiclustered nodes in simulated and biological graphs have similar characteristics. Indeed, multiclustered nodes have higher average degree and betweenness than monoclustered in both types of graphs (data not shown).

When OCG is used to cluster a PPI network, multifunctional proteins are identified at the intersections of the overlapping clusters. Interestingly, the top 10 most multiclustered proteins are important transcriptional regulators and signaling proteins which are integral parts of most cellular processes. This emphasizes the fact that functional modules can be interconnected through the regulators they share. It, therefore, appears that OCG could represent a valuable tool to investigate cross-talk between processes.

Funding: CNRS (PEPS grant from the STII department of the CNRS to A.G.); ANR as a Piribio grant (09-PIRI-0028-1, Moonlight project to C.B.) and as partner of the ERASysBio+ initiative supported under the EU ERA-NET Plus scheme in FP7 (09-SYSB-0008-01 ModHeart project to C.B.). B.R. is a PhD fellow of the AXA Research Fund.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

†The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first two authors should be regarded as joint First Authors.

‡Present address: INSERM, U625, GERHM - Université Rennes 1, F- 35042 Rennes, France.

REFERENCES

- Adamcsek B., et al. CFinder: locating cliques and overlapping modules in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1021–1023. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn Y.-Y., et al. Link communities reveal multiscale complexity in networks. Nature. 2010;466:761–764. doi: 10.1038/nature09182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aittokallio T., Schwikowski B. Graph-based methods for analysing networks in cell biology. Brief. Bioinform. 2006;7:243–255. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbl022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelelli J.B., Reboul L. Proceedings of JOBIM 2008. Lille: University Press; 2008. Network modularity optimization by a fusion-fission process and application to protein-protein interactions networks; pp. 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J., et al. Integrative gene network construction for predicting a set of complementary prostate cancer genes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1846–1853. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelt H.J., Dress W.M. Weak hierarchies associated with dissimilarity measures; an additive clustering technique. Bull. Math. Biol. 1989;51:133–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02458841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthélemy J.P., Brucker F. NP-hard approximation problems in overlapping clustering. J. Classif. 2001;18:159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Brohée S., van Helden J. Evaluation of clustering algorithms for protein-protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:488. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brucker F., Barthélemy J.P. Eléments de classification: aspects combinatoires et algorithmiques. Paris: Hermès; 2007. p. 438. [Google Scholar]

- Brun C., et al. Functional classification of proteins for the prediction of cellular function from a protein-protein interaction network. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R6. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun C., et al. Clustering proteins from interaction networks for the prediction of cellular functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diatta J., Fichet B. Quasi-ultrametrics and their 2-balls hypergraph. Discrete Math. 1998;192:87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Diday E. Orders and overlapping clusters in pyramids. In: de Leew J., et al., editors. Multidimentional Data Analysis. Leiden: DSWO Press; 1986. pp. 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fichet B. Data analysis: geometric and algebraic structures. In: Prohorov Y.A., editor. First World Congress of the Bernouilli Society Proceedings. Utrecht: VNU Science Press; 1986. pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Finn R.D., et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futreal P.A., et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh K.I., et al. The human disease network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8685–8690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701361104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann C., et al. SimCT: a generic tool to visualize ontology-based relationships for biological objects. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:3197–3198. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J. Seven types of pleiotropy. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1998;42:501–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs I.A., et al. Community landscapes: an integrative approach to determine overlapping network module hierarchy, identify key nodes and predict network dynamics. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchaiev O., Przulj N. Learning the structure of protein-protein interaction networks. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2009:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühner S., et al. Proteomeorganization in a genome-reduced bacterium. Science. 2010;326:1235–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1176343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M.E. Fast algorithm for detecting community structure in networks. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft. Matter Phys. 2004;69:066133. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.066133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M.E. Modularity and community structures in networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8577–8582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601602103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palla G., et al. Uncovering the overlapping community structure of complex networks in nature and society. Nature. 2005;435:814–818. doi: 10.1038/nature03607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paupert J., et al. Transport of the leaderless protein Ku on the cell surface of activated monocytes regulates their migratory abilities. EMBO Rep. 2007. 2007;8:583–588. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto C., et al. APID: Agile Protein Interaction DataAnalyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W298–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przulj N., et al. Functional topology in a network of protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:340–348. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souiai O., et al. Functional integrative levels in the human interactome recapitulate organ organization. Plos One. 2011;6:e22051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharan R., et al. Network-based prediction of protein function. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:88. doi: 10.1038/msb4100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.